Will the next great Japanese designer come from Coconogacco fashion school?

Interviews by Jun Ishida

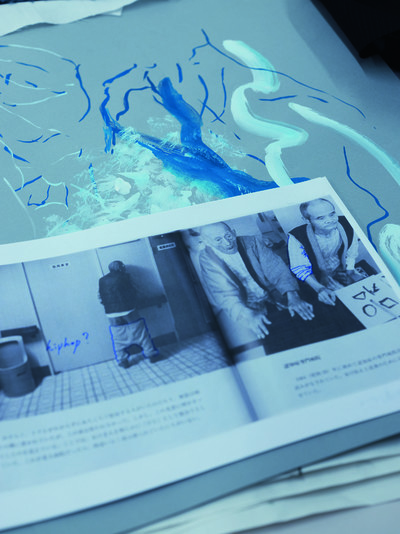

Photographs by Takashi Homma

Will the next great Japanese designer come from

Coconogacco fashion school?

Avant-garde Japanese design has been an essential component of the global fashion ecosystem since the late 1970s, thanks to the likes of Yohji Yamamoto, Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo, Junya Watanabe and Jun Takahashi. Today, in a neighbourhood of clothing wholesalers in east Tokyo, a fashion school called Coconogacco is building on that legacy. Founded in 2008 by Yoshikazu Yamagata – an alumnus of Central Saint Martins in London who worked for John Galliano in Paris before returning to Japan to launch fashion brand Writtenafterwards – the school has a mission to create a fashion culture and a creative environment that helps each designer achieve his or her own, unique vision. It’s a desire encapsulated in the very name: a play on words meaning both ‘school of the individual’ and ‘school right here’.

In its 13-year history, Coconogacco has produced more than 1,000 graduates, including Tomo Koizumi, who debuted at New York Fashion Week in 2019 and was selected as a finalist for the 2020 LVMH Prize, and Akiko Aoki, who was nominated for the 2018 LVMH Prize and won the Mainichi Fashion Grand Prix Newcomer Award, one of Japan’s most prestigious fashion awards.

At present, about 100 students attend classes every Saturday at Coconogacco. Yamagata participates in every class, bringing his experience both as a teacher and award-winning designer (in 2015, he was the first Japanese creative to be nominated for the LVMH Prize). System spoke to Yamagata about his motivation for founding the school and why it produces so many promising designers, before asking some of the current students: ‘What makes Coconogacco unique?’

Coconogacco founder and director

Yoshikazu Yamagata

Jun Ishida: When did you start becoming interested in fashion?

Yoshikazu Yamagata: It began in middle school. I wasn’t good at studying or communicating with others, so I had this huge complex. My interest in fashion grew gradually as I figured out how to hide that complex, or rather, how to dress to feel more confident. It wasn’t until I was in high school that I really got into it.

When did you start thinking about becoming a fashion designer?

I started to think fashion designers were cool in high school. I was born and raised in the countryside; there was no place around me where I could buy fashionable clothes. Instead, I started reading magazines and recording TV shows about fashion, watching them over and over again. The designers were so cool when they appeared on the runway at the ends of their shows; I admired them. At that time I still lacked self-confidence, so even when I began at fashion school I chose the fashion business course instead of the design course. I even chose a school in Osaka instead of the one in Tokyo where I really wanted to go.

You said you lacked self-confidence, but you still made the decision to leave Osaka to study at Central Saint Martins in London. What prompted that decision?

Something didn’t feel right at the school I was in, so I dropped out after one year and decided to go to a language school in London, without any clear idea of how to go on from there. Then I started to think about what I really wanted to do, and that led to the decision to try out for Central Saint Martins.

How were classes at Central Saint Martins?

I started with a short two-month course and then took a one-year foundation course, where I studied not only fashion, but also art, architecture, and design in general. Then I went on to study in the degree programme for fashion, but it was very loose. [Laughs] You receive a briefing for the assignment and then you’re left on your own to make something. You do get a few chances to talk to the professor before presenting, but there was never any pressure.

Was it different from Japanese schools?

In Japan, there are a lot of classes and mainly technical things are taught. In Central Saint Martins, there is almost no teaching of technique; it’s mostly about making students think. The students already have a certain amount of knowledge and they are highly motivated, so the laissez-faire approach works well.

What was the thing you learned at Central Saint Martins that has influenced you the most?

The atmosphere of freedom. The school was creating things with such a free spirit, and that atmosphere was directly connected with fashion. This direct connection is something that I didn’t quite feel in the school I attended in Japan.

During your time studying abroad, you went to Paris and worked for designers, including John Galliano. What did you learn from him?

I think Galliano is probably the designer who has influenced me the most. For him, anything goes. All materials are of equal value, and he can turn what people consider cheap or trashy into something full of potential. He also had the ability to come up with what is best for a particular moment in time. It really was amazing.

After returning from London in 2005, you founded Writtenafterwards in 2007 and Coconogacco the following year. The school and Writtenafterwards share a similar idea that you’ve described as: ‘Building a new relationship between people and fashion through dialogue with their hearts. Fashion is not the design of clothes, but the design of human processes and trends; it is a communication tool.’ How did both the label and school come about?

The concept of Writtenafterwards is something I had thought about since my days at Central Saint Martins. I was interested in the histories and stories behind people’s various outfits and how they came to be. That’s how the concept was born, and it certainly has a lot in common with the school. People often say that what we’re doing with the brand and the school are two different things, but what we want to do is actually the same: to convey what I call the ‘endearing sweetness of dressing up’.

What do you mean by that?

It’s endearing that people wear clothes and dress up, and that we do that unconsciously as a species. A person’s humanity oozes out in the way he or she wears clothes.

‘The Japanese saying i shoku ju – clothing, food, shelter – that describes the necessities for life, begins with i or ‘clothing’. I don’t think that’s a coincidence.’

What kind of school did you want to create when you started Coconogacco?

When I returned to Japan, I was asked to give a lecture at a fashion school. I talked to the students there and felt that some had the same kinds of concerns as I had had: they were studying fashion, but were still wondering if the school they were attending was somewhere they could actually learn about the latest fashion. That’s when I decided to become someone who passed on my knowledge of contemporary fashion. Also, in Japan’s educational environment, it was difficult for students to know exactly what they needed to learn in order to become a fashion designer, so I wanted to communicate that as well.

Did you find that the fashion education field had changed much since you’d left Japan?

The reason I left and the reason I started this school when I returned are the same. I was always a low achiever in school, and even when I went to a fashion school in Japan, I was one of the less able students. In London, I was able to enrol at a school where people who wanted to study fashion had come from all over the world. The whole value system was completely different from that in Japan. I wondered where this difference came from, and from there I became interested in the educational environment. I began to do a lot of my own research and visited schools in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Italy. Experiencing those different cultural backgrounds and styles of education meant I could look at Japan’s educational environment from a wider perspective when I returned.

What differences did you see in the value systems between Japanese and European schools?

Western clothes are the norm today, but it is actually a culture that only really took off in Japan after the Meiji era; the history of these clothes in Japan is very brief. After the Meiji era, places to teach fashion were established, starting with bridal training schools, followed by sewing schools, and then vocational schools. What was taught first and foremost was how clothes were made and the necessary techniques, and so that became the basis of fashion education in Japan. On the other hand, many schools in Europe, especially those that produce designers, are affiliated with art universities. That means that they hold to artistic values that put an emphasis on conceptual thinking. For example, in Japan, if there was an assignment to make a skirt, the first step would be to learn how to make an A-line skirt, but in Europe, you would start by questioning the very concept of a skirt, which creates the possibility of designing something unprecedented. Of course, in Japan you have the advantage of being able to learn the techniques; the country is very advanced in terms of fashion-related archival activities, and there is a lot of passion and interest in doing research. I thought it would be great if students could have a choice between the two approaches, by helping them understand the differences between Japan and Europe, and at the time, there was nowhere they could learn that.

The names of Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto and Issey Miyake come to mind when discussing any dismantling of the concept of fashion. Do you think this is a characteristic of those Japanese designers who gain international acclaim?

Kawakubo-san and Yohji-san are graduates of Keio University, and Miyakesan is a graduate of Tama Art University. In my opinion, one of the reasons for their success is that they were able to combine a strong liberal-arts background with something more specialized. Kawakubo-san and Yohji-san also went to Setsu Mode Seminar, the art school founded by illustrator Setsu Nagasawa and known for its free-spirited approach. I think it’s important to have the kind of eclectic quality that they have at Setsu, and in some ways we try to be like that today.

What do you mean by eclectic quality?

I never attended Setsu Mode Seminar, but I was told that Setsu-san would just be there, without teaching anything in particular, and that people of all ages and types would gather, attracted by the atmosphere. It was a meeting point where people from all walks of life could come and go; I wanted to recreate that feeling. To help students get onto the international stage, they need to learn about the differences in history, politics, culture and thought between the West and the East. So, in our school, they first learn about their own position as a Japanese person and then conduct research on their own roots. The more they learn about their roots, as well as their problems, complexes, and unconscious habits, the more they are able to make links with current social issues, and the stronger their work becomes.

‘There are many things that slipped away as Japan and Asia adopted a culture of Western clothing. The school consciously picks up on these things.’

What kind of techniques do you use to encourage that process?

Our students all conduct independent, self-directed research and then we also make time for them to discuss work with each other. As they actively share the production process, they come to understand the differences between themselves and others. In the field of education, teachers tend to make assumptions about students and instil old values and hierarchies, but I think that believing in the potential of all students is the most important thing. We also invite people from other fields, such as philosophy, linguistics and physics, to give critiques and tutorials, so that we are not confined to fashion alone. For example, we once invited a Noh actor to give a lecture. Noh costumes are made up of large, overlapping, flat surfaces, and by learning how these volumes move with the body, students could sense that Japanese clothing has emerged from a different background to Western clothing. There are many things that slipped away, as Japan and Asia adopted a culture of Western clothing. I want to pick up on these things and not overlook them. It’s no use doing the same thing as in Western schools; I’m always conscious of the things that can only be learned here.

The school has several courses. Could you describe them?

The main courses are the primary and advanced courses. The primary course, as the name suggests, teaches the basic elements, starting with the breadth of fashion expression. It consists of lectures, assignments and workshops, and the content of the classes is broad, from making materials to taking photographs, thinking about concepts, and spatial expression. The goal of the advanced course is to create a final piece of work, but it can be anything students want to make; it really doesn’t have to be fashion. The most important thing is that the students find the one thing they really want to do, so it can happen that someone who starts out wanting to make clothes ends up doing dance.

What kind of students attend the school?

Students come from many different backgrounds. Their age varies, from teenagers to people in their eighties, and they work in diverse fields. They all come to us because they want to combine their work with fashion. After studying at the school, some of them return to their own jobs.

It must take a lot of energy to run a school, while also running your own label. How do you manage to sustain your passion for both?

I don’t really know. At the root of it all is my own wish for fashion to be properly passed on. I might often think that fashion is superficial, but it has always been a part of human history. The Japanese expression i shoku ju – clothing, food, shelter – that describes the necessities for life, begins with i or ‘clothing’, and I don’t think that’s a coincidence. As a scholar once told me: ‘We can survive without a place to live, and we can go on without food for a few days. But if you are naked, depending on the environment, you could die within a day. Clothing is crucial for protecting life.’

Are you influenced by the school and the students?

Of course. I have a lot of respect for my students. Being constantly in this environment, I naturally come into contact with contemporary fashion, which allows me to work with it without it feeling strange.

Have the significant digital advances in recent years brought about any changes within the school?

The Covid-19 crisis has led us to begin incorporating digital elements into the classes, although it is still a process of trial and error. We don’t actively teach about digital forms of expression; I just introduce it as a possibility. I think it would be interesting if something were to come out of it, and if a student created a digital work instead of an actual object.

What other changes did the pandemic bring about?

We usually hold annual student presentations in Tokyo, but this year we are thinking of doing it somewhere more provincial. There has been talk of holding Lidewij Edelkoort’s next World Hope Forum in Japan, so we are thinking of hosting the Forum and the and streaming them worldwide. Yamanashi is home to many artisans and is rich in nature, and I would like the presentations to reflect the unique qualities of the place. The crisis has created physical distance, but in presentations based on online platforms, the value of physical distance has changed; there is now more equality of access, and it is easier to shine a spotlight on remote and unexplored areas. The school itself doesn’t have to be limited to Tokyo, either. I used to run a branch school in Fukuoka once a month, with fewer than 10 students and at a different location each time. The venue could be a temple, a beach house or a farmhouse. We set up chairs in these places and brought the students’ works for critique. A change of location changes the way you think, and by doing something that has seemingly nothing to do with fashion – at the farmhouse, we even dug potatoes – you come to see how these things do, in fact, connect back to fashion. This is my ideal method of education.

‘My country Myanmar is currently undergoing a coup d’état. I asked my mum to send me my childhood bedsheets, curtains, and traditional clothes, so I could turn these ‘ordinary’ items of sentimental value into something special, to create a sense of nostalgia for the peaceful times we had.’

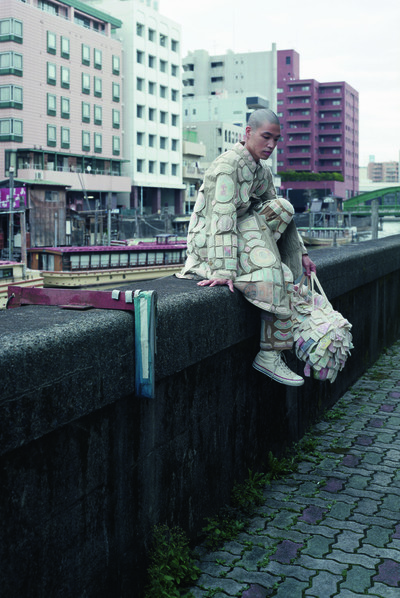

Yang Han, 26

From the collection of Yang Han

Tell us about your collection.

It started when I was exploring my roots, which I did by collecting pictures and asking my family questions, since I couldn’t go back to my homeland, Myanmar, because of the coronavirus crisis. I asked my mum to take pictures of our home – like my room, living room, dining room – then to send me some of my childhood bedsheets, curtains, and traditional clothes. My aim is to turn these ‘ordinary’ items of sentimental value into something special and so create a sense of nostalgia for the peaceful times we had, but which are now being threatened. Right now, my country is undergoing a coup d’état.

What’s the best thing about Coconogacco?

That I can be my truest self, and meet people from all walks of life.

Which person in fashion do you most admire, and why?

It has to be Leigh Bowery. He taught me to dare to be myself, and was a source of mental support at a time when I couldn’t find that from anyone else.

What do you think a younger designer like yourself can express to the world through fashion that a designer from an older generation could not?

As a Burmese person, I believe it would be a political statement. If done wrong, the older generation would get into trouble, even be sent to jail, but now, with social-media networks, we young designers can express whatever we want.

Where do you want to be professionally in five years’ time?

My aim is to assemble a small team, start my own brand, and have some impact on my country’s fashion scene.

‘Right now, my inspirations are the robot special effects I used to see on TV when I was a child. I created this piece with the intention of wearing it myself.’

Karu Miyoshi, 25

From the collection of Karu Miyoshi

Tell us about your collection.

My inspirations are the robot special effects I would see on TV when I was a child. My visual references are animé, Finn’s magically enlarged legs on [cartoon series] Adventure Time, and the plump legs seen in ukiyo-e [traditional woodblock prints]. I don’t have a particular style that I want to create. I plan to continue expressing myself through various media, not just fashion. I created this piece with the intention of wearing it myself.

What’s the best thing about Coconogacco?

This is a place where you can actually see and hear the opinions of people who might not have experience in making clothes, but have other experience, like in theatrical performance, painting, operating heavy machinery, and other things. People who approach fashion from all directions.

Which person in fashion do you most admire, and why?

Craig Green, because anything he creates is cool.

What do you think a younger designer like yourself can express to the world through fashion that a designer from an older generation could not?

This question is too difficult to answer at the moment. I do not know that yet.

Where do you want to be professionally in five years’ time?

Nowadays, art and fashion go back and forth between each other, and I don’t think there is any need to separate them. From now on, I would like boldly to challenge every medium of expression, and in five years, I would like to attract attention from various fields as a promising newcomer.

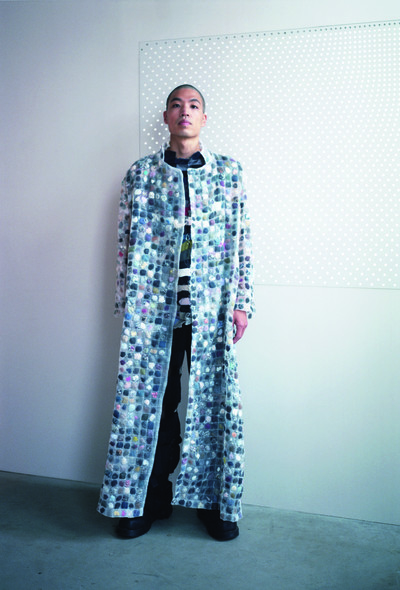

‘I’ve embellished vintage wear with Japanese food labels from the 1920s onwards, each wrapped in fibre. Product packaging, like fashion, is created purely to convince and persuade.’

Tomohiro Shibuki, 34

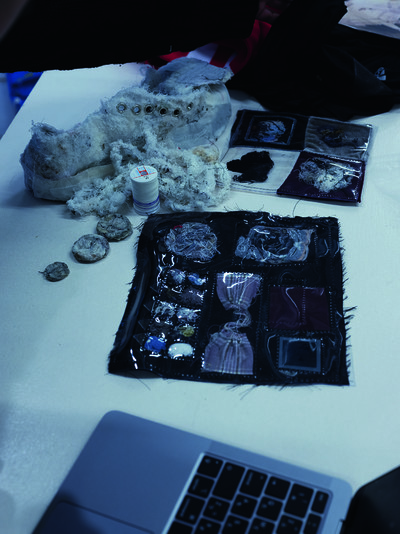

From the collection of Tomohiro Shibuki

Tell us about your collection.

My work as an artist is based on the idea of blurring the boundaries between everyday objects to create work that leaves room for the imagination. In my collection, I used the technique of covering various objects with fibres, like vintage wear I’ve entirely embellished with Japanese food labels from 1920s onwards, each wrapped in fibre. The encapsulated objects are trapped, and appear as ambiguous, altered entities. The other part of the collection is based on food and product packaging from my own life under the pandemic. In the collection, I contrast each end of this 100-year time span, and the hyper-personal with the popular. Product packaging, like fashion, is created purely to convince and persuade. In a sense, that purity of purpose has a kind of nakedness, so the project is also an act of covering these naked things with warm hair, like drawing a blanket over a naked person.

What’s the best thing about Coconogacco?

It’s provided me with the time to reflect upon myself.

Which person in fashion do you most admire, and why?

Martin Margiela. I was really influenced by the way he reconstructed things through strange combinations of materials, and the way he showed respect for all kinds of clothes from the past.

What do you think a younger designer like yourself can express to the world through fashion that a designer from an older generation could not?

The current generation is in an environment where it is easy to transcend barriers between different fields and disciplines, and I believe that doing so proactively will have a positive impact not only in fashion but also on cultural formation in a broader sense.

Where do you want to be professionally in five years’ time?

I am hoping to expand the scope of my activities, continue to create and think, and be a person who can freely express what I want to express.

From the collection of Yang Han

‘I am not aiming to be a designer. Five years from now, I just want to be a kind person.’

Hirate, 23

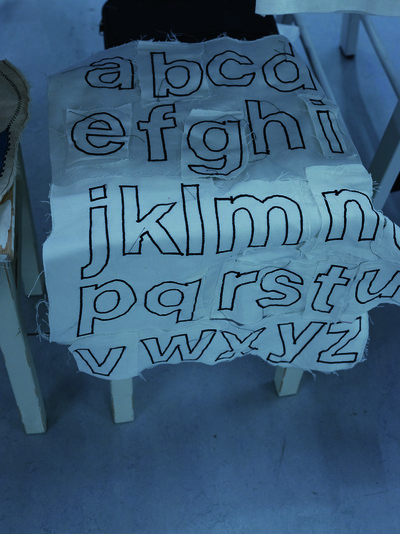

From the collection of Hirate

Tell us about your collection.

In the process of transforming an imaginary existence into a real object, I tried to give it a function as clothing. I think about the existence of my creation in this world, how it stands and how it is. In reality, it is almost impossible for my creations to be functionally worn as daily wear, but I believe that the structure itself, which is created to accept the human body, has a strong influence on the fundamental sense of the object’s existence. I am fascinated by the tremendousness and beauty of any person’s attempt to depict ‘someone’ while remaining alone in that self-expression. And I want to do that in my way, too.

What’s the best thing about Coconogacco?

Rather than dividing fashion into sections and focusing on socalled ‘practical’ knowledge, I have been able to explore it as a huge, muddy stream. While being tossed about by its vastness, I could try to find the essence of what fashion is.

Which person in fashion do you most admire, and why?

I can’t think of anyone in particular.

What do you think a younger designer like yourself can express to the world through fashion that a designer from an older generation could not?

I am afraid that I cannot answer this one. To be honest, I have no idea what the difference is between the past and the present.

Where do you want to be professionally in five years’ time?

I am not aiming to be a designer. Five years from now, I just want to be a kind person.

From the collection of Daichi Tabata

‘My references were developed during my research into the history of dementia, as well as my grandfather’s belongings and photographs. People with dementia experience what’s been called ‘ambiguous loss’, and the collection is shaped by perspectives on loss, absence and memory.’

Ei Nakamura, 20

From the collection of Ei Nakamura

Jewellery by Shun Gondo

Tell us about your collection.

I was thinking about the way dementia affects relationships between family members, something I had studied in graduate school. My references were photographs documenting the history of dementia research, fieldwork and interview data conducted during my research, as well as my grandfather’s belongings and photographs. People with dementia experience something that’s been called ‘ambiguous loss’, and the collection is shaped by perspectives on loss, absence and memory.

What’s the best thing about Coconogacco?

It’s an environment where you can express yourself, while also paying attention to trivial things.

Which person in fashion do you most admire, and why?

Yoshikazu Yamagata.

What do you think a younger designer like yourself can express to the world through fashion that a designer from an older generation could not?

An awareness of those people who have been left out of the hierarchical fashion world. A diversity of individuals rather than diversity of the whole.

Where do you want to be professionally in five years’ time?

I would like to make use of my research activities in graduate school to actively build bridges between subject areas.

From the collection of Shiori Tsuchida

‘Using the various sizes and colours of the fibres, I like to convey a perspective from the microscopic to the cosmic.’

Takahito Iguchi, 35

From the collection of Takahito Iguchi

Tell us about your collection.

I have experience working in textile testing and inspection; we deliberately apply loads to fabrics and destroy them. When I saw lots of these scraps mixed together, I thought they were beautiful and so decided to use them and other post-test fabric pieces. Using the various sizes and colours of the fibres, I like to convey a perspective from the microscopic to the cosmic. I have been collecting and sorting lint every day for two years, and I created my piece by imagining the cleanliness of lint and the act of sorting it, in the style of myself and the people around me at work.

What’s the best thing about Coconogacco?

I really like that it’s a place where people from various professions and generations can gather.

Which person in fashion do you most admire, and why?

Jun Takahashi from Undercover, because he is challenging Paris with his own style.

What do you think a younger designer like yourself can express to the world through fashion that a designer from an older generation could not?

Free expression without the boundaries or classifications that existed in the past.

Where do you want to be professionally in five years’ time?

I would like to have my own style.