The darkness and lightness of Walter Van Beirendonck’s life in fashion.

By Tim Blanks

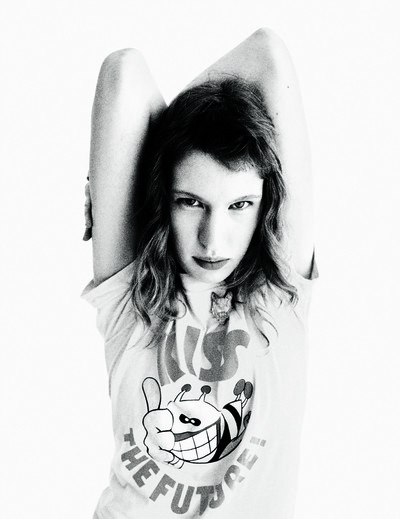

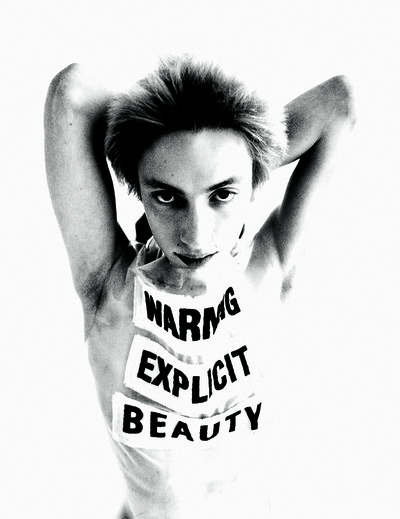

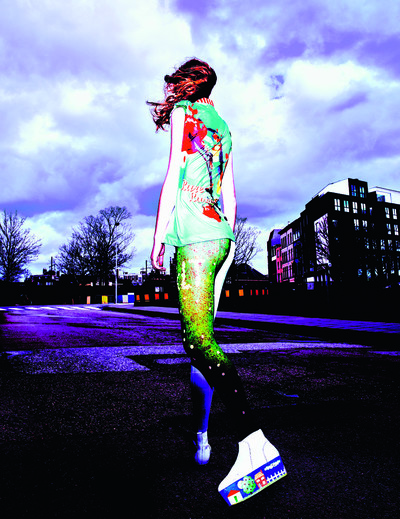

Photographs by Willy Vanderperre

Styling by Olivier Rizzo

The darkness and lightness of Walter Van Beirendonck’s life in fashion.

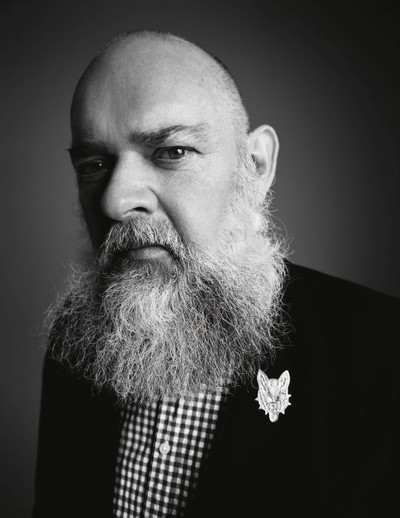

Did Walter Van Beirendonck grow the Beard or did the Beard grow Walter?

There was nothing else like it in the well-groomed fashion world when he stopped shaving in 1988. Since then, the Beard has done a lot of PR for him, good and bad. Add a Mohawk and a Mad Max glower and it made him an intimidating road warrior. It was too ZZ Top for Berlin’s top techno club: Walter was turned away at the door, even though everyone else in the queue was wearing his label W.&L.T. He bounced back with the rise of the bear. The Beard connected him with a more welcoming subculture. Now, in the Age of the Lumbersexual, big beards are everywhere. No longer threat or curio. I’ve been walking in the street with him in Antwerp when kids have called out ‘Santa’. What’s next? Kawaii Karl Marx?

The Beard made him an avatar, like Donatella’s hair and everything about Karl. Obviously, the Beard is attached to him. Yet Walter is not so attached to it that he wouldn’t shave it off, with one caveat: he’d only do it ‘to raise a lot of money for a good cause connected with nature and animals’.

Walter is the head of the fashion department at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, from where he graduated in 1980. He was one of the group of graduates known as the Antwerp Six who introduced a new Belgian fashion to the world. Among them was Dries Van Noten, Ann Demeulemeester, and Dirk Van Saene, Walter’s partner since 1978. (Martin Margiela was an honorary member.) For decades, the couple has lived a bucolic existence in Zandhoven, the small village in the Belgian countryside where Walter’s parents owned a car-repair garage, where he grew up, and where he has always dreamed his worlds awake.

One of his earliest collections was called Let’s Tell a Fairytale. Like that other Walt, except this one’s magic kingdom embraced environmental apocalypse, revolution, gender politics, sexual fetishism and body modification. Contrasts of fairy tale and dark fantasy, innocence and experience, enchantment and transgression have shaped his vision from the beginning. It’s Disney versus Dionysus. Indeed, opposition is central to Walter’s work: the utopia of Close Encounters of the Third Kind versus the dystopia of A Clockwork Orange; Snow White versus Pretty Woman. He loves all these things.

‘Just making clothes is not enough,’ Walter told me long ago. He has often tried to add socially aware content, through the words and slogans he uses, or the names he gives collections. His most famous is probably Kiss the Future. After the year we’ve just had – and the year we’re now having – the future isn’t looking particularly kissable, and even though Walter has always had a thing for sci-fi and aliens and UFOs, embracing every futuristic cliché, he called his last collection Future Proof – Stop Monsters Now. A change of heart? Apparently not.

Tim Blanks: Were you being ironic when you called your last collection Future Proof?

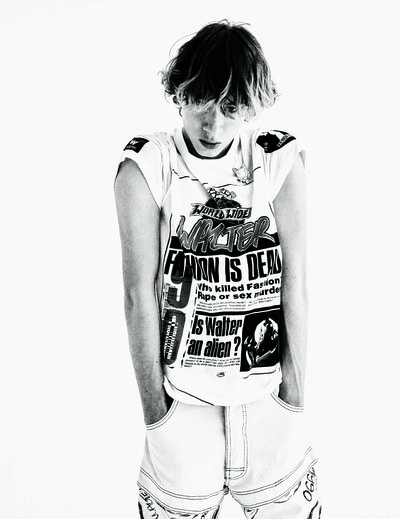

Walter Van Beirendonck: No, it was inspired by the fact that for the moment I receive a lot of social-media interest from these kids who are 16, 17 ,18, who are discovering my 1990s collections and starting to buy them as vintage, which is a strange phenomenon. That’s why I had the idea to reuse all my old characters and icons, with the thought that they will probably be popular again in another 20 or 30 years’ time and attract a new, young audience then.

Do you think there is an anarchic quality in those clothes that appeals to kids?

It could be. I think they feel the energy in a different way to what you have with the anarchy of punk. But there is also a punk feeling if you put them back in their original context and compare them with other collections from that period. At the time, it was a statement to do those kinds of clothes, it was about being free and adventurous with new materials, techniques, shapes and forms. It was also a reaction to the fashion world. Kids can probably pick up on that.

Does it make you feel you’ve always been ahead of your time?

That is difficult to say. I did the right things at the wrong time. Just one example: I did so many multicoloured sneakers that I then developed for commercial collections, but I did them much too early and I couldn’t sell them. Then a few years later, people were ready and they were buying them en masse. That happened several times in my career when I was so excited about something and the market didn’t pick up on it and it was a disappointment for the people I was working with.

It feels to me like the pandemic may offer fashion a chance to establish a different rhythm, so it is not all about doing the New Thing. There will be chances to go back and reflect a little more, maybe bring old things back into the collection. That is what I wanted this conversation to be about really, the idea of reflection. What you’ve learned, what you’ve left behind.

I’m not someone who reflects a lot. Most of my decisions are spontaneous: I see something; I read something; I am attracted to it; I go deeper; I do some research; I get the subjects into my work – and the collection comes alive in a spontaneous way. The thinking process happens mainly in my collages, my sketches. That is the reflection I’m doing, during my working process.

‘When I was 14 years old, I’d wear platform shoes and go to London to buy the most extreme things because I wanted to express myself through clothes.’

You must see themes, though.

Yeah, yeah, it was very obvious in my exhibition that I am attracted to certain themes. The fairy-tale theme is always there, and aliens and UFOs also come back a lot. The subject of gender comes back regularly, but I also try to discover new themes. It is very like searching for myself.

Fashion as therapy. And if you look at your body of work, your therapy has been particularly provocative. You’ve been exploring the intricacies of human sexuality in your collections for years.

I can imagine that it feels provocative for the audience, but for me it was a clear decision to push my boundaries, not only in private. I thought each time that it was the right moment to try to do something that was not convenient in a certain way. For me, it has never simply been about provocation, but pushing further my fashion and my ideas. Subconscious provocation, maybe, as a new way of approaching men’s fashion.

Has the therapy worked?

Making fashion makes me happy and I am still enjoying it, so I think it works.I have a rather good balance, especially over the last 10 years. I have the feeling it is under control and I can do what I want, so that is a good feeling.

What do you think is the purpose of your work?

How to communicate through clothes. I don’t know that everybody gets the right message, but at least I can show what I want to express through the collection. The communication has always been all about freedom. That is why I went through all these stages: to become a free man and to do exactly what I want. And that is why I had to stop with W.&L.T. in 2000 because I felt that I wasn’t a free designer anymore. For me, the way I am working and how I am involved physically comes

straight from my heart. So that is why it is so important to me to take my own decisions.

Independence can be a real battle in fashion. I imagine there were times when you felt like stopping.

Yeah, but I never did. Back in the 1990s, my goal was to make a project for young people, but I went through a very difficult period with different manufacturers and it all seemed impossible. Then I arrived at Mustang in 1992 and they gave me the opportunity to do exactly what I wanted. After the first W.&L.T. show, they felt there was so much potential to attract attention to their label and to me that they gave me an unlimited budget. That was the whole thing with the huge shows and so much press attention. So I literally went from a period that was very dark to something that was very bright, and that is how my career has always gone, darkness to light, but always with a lot of energy to keep it going. So I never had the feeling that I had to stop.

‘The Wall was still up, and I crossed into East Berlin, wearing my big Montana coat and Plexiglas glasses; people looking at me like I was an alien.’

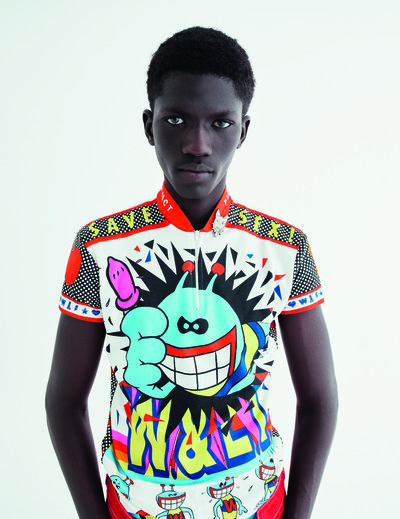

The first W.&L.T. collection was Spring/Summer 1993, appropriately titled Wild and Lethal Trash! Fast-forward to 25 January 1996: we were in Paris for Autumn/Winter 1996/97 and a collection called Wonderland. It would prove a watershed, its mens- and womenswear (children, too) becoming the grail for Walter’s new acolytes. The presentation, which took place in a huge mushroom-shaped tent, had three distinct visual strands. First up were androidlike Forty Kinky Kings modelled on mad King Ludwig of Bavaria, whose castles on the Rhine inspired the iconic centrepieces of Walt Disney’s kingdoms. Ludwig’s original versions were printed on sweats and T-shirts, along with two swans, who Walter said represented Dirk and him. Then came Forty Bears, cast from the bear community in London, who walked hand-in-hand with little W.&L.T.-ers, who wore miniversions of the big boys’ outfits. Last were Forty Colour Stars, spacy, bodymodified, extraterrestrial. All the contrasts of Walter’s work were starkly on display: innocence and experience, enchantment and transgression, made more so by the fact that the collection

incorporated motifs based on sex toys. ‘I’m a catalyst,’ he said. ‘I’m interested in strange connotations.’ The collection wasn’t universally understood. New York Times fashion critic Amy Spindler wrote: ‘Mr. van [sic] Beirendonck’s bears all came out with little boys, and the suggestive (and sophomoric) program notes left little doubt about the designer’s meaning. This show was a huge misstep.’ The bear community wasn’t too pleased either. Connotations breed miscommunication.

Those W.&L.T. shows were like massive, cast-of-thousands manifestos. I think that is something that kids also respond to now, not just the clothes, but the whole circus that you created. That just doesn’t exist any more.

It was rather crazy to create first all the clothes and then the ideas for the show in six months, but I had a good team and, of course, the money, so I had the opportunity to fantasize about how to put my ideas on the catwalk, to do incredible casting all over the world, to work with fantastic hair and make-up people, and with Stephen [Jones] for the hats. There was a lot of synergy between all these creative people and each time there was something – an idea or a space or a catwalk – that really worked very well. I enjoyed putting together those productions.

You were a different person back then.

I don’t think so; I don’t feel so different, but I work on a different scale now. It was not about being young or about the energy of youth. I’d already been in fashion for more than 10 years; it was not the beginning of my career. No, I was rather organized coming up with the ideas, knowing how to make them, how to put them together on the catwalk. I was not working with producers. All the ideas came straight from me and my interests, and then we found solutions.

At that time you looked like something out of Mad Max; it was an extremely aggressive, confrontational look. If you weren’t a different person, you played a different game in those days.

Yeah, it was a little bit like how a pop star would play the game, which I enjoyed because I always wanted to be a pop star, but could never sing. The way I approached the audience was really as a person combining all the elements that I have inside me. There was an aggressive part and then also something more humoristic, almost like a cartoon figure. Also, at that time a fashion designer was supposed to look very slick and then I arrived there with the beard and as a heavy man, not really how a normal fashion designer was conceived, I guess. Then I was wearing hardcore clothes with spikes and patches. I created my own persona, and then tried to make it a fantasy figure almost. It all came together very spontaneously; I was not thinking about what my next image would be. It was how I lived, and I was bringing things together. It was also how I liked to combine all these different things at that time. I enjoyed going to a leather bar one day and seeing an incredible exhibition the next day, mixed up with seeing a romantic movie like Pretty Woman. I am someone who enjoys all these different things – and Pretty Woman is my favourite movie.

There’s no irony when you say that.

No, I am serious. We enjoy other movies, but just to tell you that I don’t mind playing with these contrasts in my life, in my work, in everything.

Did you feel you had kindred spirits in fashion while you were doing W.&L.T.?

I was a little bit on my own then; I was rather disconnected from the rest of the fashion world. At that time, I was on the official calendar in Paris between Dior and Comme des Garçons, which felt strange but also incredible to be surrounded by people I had so much respect for. The person I always connected with as a designer was Rei Kawakubo. I don’t know that we have anything in common, but I always appreciated her adventurous approach to fashion. At that time, I felt the most respect, the most interest for, and also the most common cultural feeling with artists. They came to my shows, which were featured a lot in art magazines, and they experienced them as performance. For them, it was a step beyond the fashion show. And people like Erwin Wurm and Sylvie Fleury would contact me for collaborations; Sylvie used the rubber video in one of her installations. Choreographers, dancers, ballet people were really interested in the W.&L.T. show. Those shows were so much about performing and showing the body in a different way. Also the casting I did, with very young people and old people, and the way I integrated them into a story. Like the show with all the birds of paradise dancing with the gas masks and the stilt-walkers, and the white people with the deformities. It was a story and also kind of an event that was happening, and I think that was really appealing to people who were in performance.

‘For me, it’s never simply been about provocation, but pushing further my fashion and my ideas, as a new way of approaching men’s fashion.’

Do you miss that? Can you condense that feeling into what you do now?

I mean, it was great to do and I enjoyed it, but it was also very demanding. Fittings alone took two days and a night. It was very intense. I don’t think it suits the times any more, nor how I am now as a designer. I don’t think I would like to do it that way. A small size fits better with this world.

When did you first meet Rei Kawakubo?

Back in the early 1990s when we were still all together – I think Martin [Margiela] too – the Six went to Tokyo to do a show during fashion week, and we also went to some shows and visited Rei Kawakubo’s atelier. We were all like 25 or 26. She wasn’t there, but we could see the office where she worked. There was a bunch of flowers on the table and one of the people who was guiding us around said, ‘You have to excuse me for this. Normally, there are no flowers, but this is because someone gave it to Rei for after the shows.’ I’ll never forget her making excuses for the flowers. We also did shows in different cities because we were part of a government-organized visit, and we were a little bit like the entertainment. For us, it was incredible to discover Japan, but we never had the right audience. It was always people who were invited by the government, never the fashion press. So we were completely anonymous in Japan, doing our shows with our first collections, the ones we made for the Golden Spindle prize. Then in 2001, I went to Paris with the idea of combining Rei and Chanel in one exhibition. We had a very good conversation. Well, it was actually Adrian [Joffe, president of Comme des Garçons, and Kawakubo’s husband and translator] who was talking up and down a little bit about the idea. Then it went very silent, and Rei said, ‘No exhibition.’ And I thought, ‘Oh no, here we go, it’s not going to happen.’ And then she said, ‘Show.’ And in fact, it ended up that the Chanel part was the physical exhibition that you could visit, and the Comme des Garçons part was five shows that I did with her collection of that moment. I did the styling in a different way each time. The venue was always different, and so was the audience. Rei came to the first show we did in Antwerp – that was the one where all the Belgian designers were in the first row. From then on, it was really nice proposing my new ways to style her collection every month. I would send Polaroids to Tokyo, she would look through them and say, ‘OK, but you have to change this or that.’ It was a very intense and respectful collaboration, and it was incredible to do, because of course, her presentations can be a little bit cold, but I could change the hair, the make-up, the shoes they were wearing. The models also.

Did an experience like that affect your own approach?

It gave me a lot of courage. To know her spirit and how difficult she is and how she trusted me to do whatever I wanted was so incredible to feel as a designer. And the way she works opened up my mind: you can do very experimental pieces, yet still do discreet and commercial products and sell garments. It is so difficult to be very adventurous and also be commercial, to combine that in a good way. It really works with Comme des Garçons.

Do you think you’ve been able to do that?

I’ve tried to keep that balance as much as possible. The image that you project to the outside world is also something that you have to keep in careful balance. When you get out of balance, you lose your credibility.

Do you wish you had been more successful?

Oh, that is easy to say! No, but I wish that I had had a bit more money, because even in my best times, it was always a struggle. Sometimes I am stubborn, and it was not easy to survive and go on and also to keep up the quality and say what I wanted to say and do. That is not an easy thing.

‘At that time a fashion designer was supposed to look very slick and then I arrived with the beard and as a heavy man, not really normal.’

Walter could always measure his success against the designers who also graduated from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts between 1980 and 1981: Ann Demeulemeester, Dirk Bikkembergs, Dirk Van Saene, Dries Van Noten, Marina Yee, and Martin Margiela. With the rise of Milan, and the Japanese descent on Paris, it felt like the fashion world was opening up, and ‘For me, it’s never simply been about provocation, but pushing further my fashion and my ideas, as a new way of approaching men’s fashion.’ Gert Bruloot, who helped promote the designers’ post-graduate work in his Antwerp boutique Louis, thought it was time they journeyed further afield. So, in 1986, they were all packed into a van (minus Margiela who had left for Paris to work for Jean Paul Gaultier) and headed for the British Designer Show in London. They were an instant sensation and labelled the Antwerp Six by the local press because their names were such a mouthful. The Six (often referred to as 6+1 because Margiela is usually included) were together long enough as a group to have an international impact, until success, for some more than others, dispersed them. ‘It was like a pop group splitting up,’ Bruloot has said.

I always wondered about the dynamic of the Six. The thought of you all travelling around Japan together is lovely, like a troop of samurai. But what happened afterwards?

The period when we were intensely working together and going to the fairs was fantastic. It was a real feeling of friendship and synergy between everyone. We all had a clear input and we could really communicate, and that really helped a lot in getting to know the press and attracting buyers. Some of us were easier to accept, but the buyers were still coming and seeing everybody anyway. There was no competition because we all had a very clear direction, and the garments and the looks were very different. We’d work together during the day and then in the evening we’d have dinner together, go out dancing or to a party. Then everybody started to go their own way. The friendship is still there, but we don’t see each other so much any more.

I always got the feeling that you were the leader, because you were the most aggressive-looking one in the Claude Montana leathers.

No, no, no, I was always the stranger, but I did love those leather coats from Montana with the big shoulders. My mother also loved to go shopping and we would go and buy those pieces, which was really fantastic. I remember once we went to Berlin with the school for an exhibition. The Wall was still up, and I crossed into East Berlin with some friends. I was in my big Montana coat with my big Plexiglas glasses, and people looked at me like I was an alien.

Did you enjoy the sense of being an alien, of being a stranger in a strange land? UFOs and aliens show up in your work quite often.

I don’t think I was expecting that reaction at that time, but I didn’t mind. I never had the feeling I had to change my stuff to appeal to people, so I always did what I wanted. When I was 13 or 14 years old I was wearing platform shoes and going to London to buy the most extreme things because I really wanted to express myself through clothes.

‘I enjoyed going to a leather bar one day and seeing an exhibition the next; then mixing that up with watching a romantic movie like Pretty Woman.’

In August 2020, Walter accused Virgil Abloh of copying a look for Louis Vuitton’s Spring 2021 collection from his own collection for Autumn 2016. In the subsequent furore, some of those jumping to Abloh’s defence turned the claim of plagiarism back on Walter for the many instances of inspiration he has drawn from elements of other cultures around the world, including the Masai, Bozo people of Mali, and groups in Papua New Guinea and Afghanistan.

You say you’re stubborn, so I imagine that means you get frustrated sometimes. Do you think that has opened you up to being misunderstood? I mean, the whole issue of cultural appropriation became such a big one for you.

It is frustrating when you do things directly from your heart. Being fascinated by other cultures and suddenly you are not really allowed to look at them any more – yes, that feels very frustrating. For me, research is more to trigger my fantasy to create something. Maybe it starts from a certain inspiration, but in the end I don’t think you feel it so obviously, or even when you do feel it, I think you know it’s done with a lot of respect. There is this StyleZeitgeist podcast about political correctness in fashion, which they did two weeks after the incident, with people accusing me of not doing things correctly, and they really talk about this and how it has rewired fashion. If you look back at Jean Paul Gaultier’s collections, for example, there are so many topics that he would not be able to do any more. So the feeling that you are not able to express yourself freely any more and touch certain subjects is frustrating. I always did it with a lot of respect; I never had the impression that I was misusing other cultures or even using them in a very literal way.

I know that when people were going after you, there was also criticism of Belgium’s colonial record. It’s appalling, as is the UK’s or France’s. Any country that had an empire has blood on its hands; it’s simple. But how do you work around an issue like that in fashion? People like to say, ‘You need to do some learning.’ What did you learn?

At that time, I went from victim to accused in a few days. I was in the eye of the storm and suddenly I was blamed for doing so many things wrong. That was very much a frustrating feeling, because I felt that I was always very open-minded about my interests. I have always talked about my interests in tribes and rituals, in Papua New Guinea, for example, so for me it was very natural in the way I was working and thinking. In the changing world now, we cannot do things in the same way as before. How to deal with these things is a challenge. I know Belgium’s terrible colonial record, but I found it a bit extreme to cast me in that very bad light. I also wondered why people didn’t get in contact with me directly and talk it over instead of finger-pointing on social media, saying I did this or that. Then two days afterwards, it was all over. That is the thing with social media: it is like a storm and then it is gone. But after something like that, you learn to be more sensitive. It’s important. It’s not that I was ignorant or never opened a book. I was not in that situation; I was always the one promoting inclusivity and diversity. Now there are a lot of designers who are afraid to make a mistake, though, because they don’t want to do bad things to other people, even though that is never their intention. It creates a strange tension in the fashion world.

There are so many wrongs that need righting, so many hundreds of years of injustice that need addressing, as well as the fashion industry’s own endemic shortcomings. The environment has changed radically. You have a responsibility to your environment, to your customers, to your students as well.

My responsibility to other people was always there, as a teacher and as a fashion designer – I’ve always felt it. That is why I’ve always made so many statements in my collections. From the beginning, I was concerned about the planet, about animals, and how we were evolving. With the AIDS epidemic, for example, I felt very strongly about the safe-sex message in my collection. A sense of responsibility has long been a normal thing for me and over the years it has become even bigger. Now I feel even more responsible to think certain things over before really doing them.

You talked about frustration. As you get older, do you ever feel despair, or do you feel more resigned to the way the world is?

I don’t feel despair, no. These last years, I’ve felt rather peaceful in one way or another. I have found a balance. I do things I like and enjoy. I am very happy with my private situation, being together with Dirk, living in this house. Of course, I’m getting older and I am hoping that I can still do a lot of things in the future, but your time gets shorter, and that is the feeling that makes things a bit scary.

Do you like getting older?

No, no!

Do you go back and look at your old things and wonder how you did them? Can you relate to your younger self?

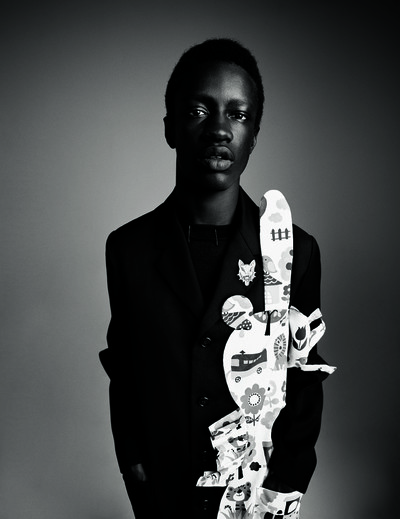

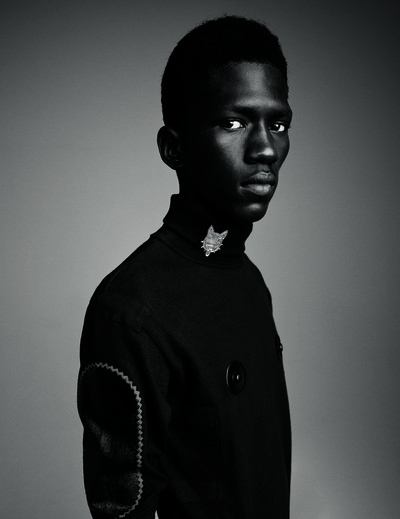

I have huge archives because I keep almost everything. When we did the shoot for System with Olivier [Rizzo], everything was perfectly displayed in the studio like a shop or an exhibition, and it felt very natural to see all these things come together. I am sometimes surprised that I did a particular piece at a particular time, because it was a fight and also a bit crazy to do things like that in the 1990s. Like the blow-up jacket. I mean, how did I come up with the idea of a blow-up jacket? And then present it to the 60 agents at the time, who were asking, ‘Why do we need a blowup jacket to show off our muscles?’ Or I had to convince them to do a fluo colour in the collection because they said, ‘No way, everything is really dark now and you’ll never sell fluo yellow.’ So I was always fighting to get my ideas into the collection. Now, when I see those pieces and I know the context I was working in, I think I was brave. I don’t have to be brave any more because I am not working with so many people now. I’m really happy I did it though. It’s not necessarily that I did it better; I just enjoy the energy that I was putting into collections at that time.

‘I literally went from a period that was very dark to something that was very bright, and that is how my career has always gone – from darkness to light.’

I think your vocabulary changes as you get older and that can be a good thing in certain ways, but you do also lose things. What don’t you like about getting older?

It is the physical side. I don’t feel it in my head, but when I look in the mirror I see that I am not the same as 10 years ago. Also, there’s the feeling of not having the possibility of going on and on and on, because physically you can’t. In the 1990s and 2000s I went on and on and on and that was an incredible feeling. I was sometimes in three different countries in a week, seeing and visiting things, talking with people, and then working on top of all that and coming up with these incredible shows and results. And then travelling the world with U2 and being backstage. That kind of feeling is gone a little bit, because it is a typical feeling you have around your forties.

In 1997, Bono invited Walter to Dublin to talk about designing the costumes for U2’s upcoming tour. ‘I was so surprised because I was not even a fan of his music,’ he remembers. ‘I love electronic music, not rock.’ It was a gauge of W.&L.T.’s impact. The invitation was accepted and Walter created signature looks for the whole band, including Bono’s notorious muscle T-shirt. The PopMart tour crossed the world from April 1997 until March 1998, its 93 shows grossing nearly $174 million. Fans were apparently confused by the band’s willingness to mock its serious image. Irony died! Yet a decade later, Bono said he considered the tour to be U2’s finest.

You said you wanted to be a pop star. When you were travelling with U2, did you think, ‘This is my world’?

It was fascinating. The premiere in Las Vegas was incredible because I stayed together with Dirk backstage at the rehearsals for literally four weeks. We were intensely together with the whole band, really working on the garments and doing alterations because there was so much stress and a lot of things had to be changed at the last minute. One day, Bono was an M, and the next day he was an S, and the day after that an L; he was changing all the time. But it was really nice to be in the middle of that very intense moment of putting together such a huge show. They were used to wearing very easy rock’n’roll looks, and suddenly they were wearing costumes, but they enjoyed working with the designer to combine that with the PopMart stage set and videos.

Are you still in touch?

We don’t see each other regularly, but the band and Bono are very respectful and loyal people.

You mentioned fairy tales and there’s always that element in your work, of exploring myths and codes. I remember we chatted a while back, and you had got into BDSM. It was this new world you were exploring, and you were excited by the idea of there always being a transgression, another world for you to explore. I guess that does follow on from talking about appropriation.

I remember you asked me, ‘What is your safe word?’, and I didn’t get what you were talking about and then afterwards I was, like, ‘How stupid is that?!’ You know that I am attracted to new worlds, but it doesn’t mean I am involved in these things. At that time I was really exploring this new world because there was a person who was actively doing it and then, of course, you start to be fascinated. That’s what it is really, a fascination more than anything. That is the main thing.

But you do manage to bring the fascination into the work. If you care to look for it, you can see it. It is like a fairytale. You have the candy colours, but the heart is dark. That balance is a very strong thing in your work.

I discovered that feeling while getting to know Mike Kelley and Paul McCarthy, who are really my favourite artists. When I visited Paul McCarthy in LA, it was sensational to see how he was expressing himself in a way that was uniting so many different universes and inspirations. It’s what triggered me to work that way, to do the candy colours and then also make the hard and rough statements.

And done all the time with beautiful tailoring, like the perfect craft with the chaos.

I am very proud of the tailoring. Right after school, I worked for almost 10 years for Bartsons. It was a Belgian company you could compare a bit to Burberry. Martin [Margiela] worked for them; Ann [Demeulemeester] worked for them, too. For a long time, I was designing traditional trench coats and very constricted and tailored pieces, and we would do that in-house with the technical people who were making the patterns. That was a huge learning experience for us all. Next to the ideas that we bring to the collections, our strength is definitely that we are able to tailor them ourselves. We are able to translate even weird ideas into tailoring – and if they are very well executed, they perform much better. I think one of the strengths of the Six was that we all had rather traditional backgrounds where we were really pushed to work in a very dedicated way.

‘I remember you asked me, ‘What is your safe word?’, and I didn’t get what you were talking about. Then afterwards I was, like, ‘How stupid is that?!’’

Do you think that by being able to craft something so well you can lure people in, and then hit them with the chaos and the transgression?

That is a little bit my working system. You attract them and once they get in, they’re surprised by the world they are entering. That is what I really enjoy, to play that kind of game with the press, with the audience, with the buyers. It’s like a dance, a little bit attracting them in and then pushing back.

Would you rather seduce people or disturb them?

Seduce and disturb them at the same time.

Speaking of disturbing, you use masks a lot; I find them scary. In a movie, when someone removes their mask, you know they’re going to kill you, because that means they don’t care if you can identify them. Tell me about your use of masks.

Of course, the idea that you can be anybody you want behind the mask is very appealing; it gives you perfect freedom. In certain worlds, you can put on a mask and you can do anything you want. That is a good feeling for me. The way I am using masks is really to create a kind of different identity, and also again the same dance I am doing with attracting and pushing back. You create an atmosphere that feels a bit uncomfortable on the catwalk and that tension can drastically change the feeling of the viewer. I find that very interesting. You are starting to use your imagination because you see something that is disturbing, and that is putting you on the back foot.

Do you think your own persona is almost like a mask? Or an avatar? Like Jean Paul Gaultier or Donatella Versace or Karl Lagerfeld? Ask people to describe Walter Van Beirendonck, what are they going to say? Big beard!

The look all happened over the years in a very spontaneous way for me. It is not that I am taking it off or putting it on; it is always there. If there is a mask, it has grown together with me and become me, and I am wearing it permanently. And then we have to think, is there someone behind it, another person? But I don’t think it goes that far.

Well, we did say that fashion was therapy. That would be an extremely heavy exercise. Who is the man behind the mask? It makes me wonder if there is one collection that means more to you than the others.

The collections that are more important are about the message I was bringing or about the reactions I got. Sex Clown [Spring/Summer 2008] was very important. I showed it in the Bataclan in Paris, because it was a static presentation. There were only 15 looks that were presented on models standing on small blocks in a big half circle that made them like sculptures. Together with very loud techno music, it was a very intense atmosphere. The collection before that had been Stop Terrorising Our World, and was the one where I was really trying to get myself back on the rails under my own name in Paris – without much success. The press didn’t react, the buyers didn’t buy, which was frustrating and disappointing. I wasn’t getting the attention I used to have before, and I just said, ‘Fuck it all, I’m going to do what I want. I’m not going to be commercial; I’m just going to do a collection that stands for everything I stand for.’ Sex Clown was very extreme with the shapes and the forms and the hats with Stephen [Jones], with an African inspiration. It came together as a very strong statement and everyone was reacting and talking about it, and it attracted buyers to the showroom. That collection was a statement of doing what I wanted. It was a statement of freedom that really had results, and I am very proud that I did it that way. If I had continued in a way that was aiming to please people, I never would have got to where I am now. Sometimes in fashion you have to please people, but with that one I didn’t want to please anyone.

‘In certain worlds, you can put on a mask and you can do anything or be anybody you want behind it. It gives you perfect freedom, which I find appealing.’

It’s interesting that you can take a long view on your work, talk about people looking at your clothes in 2050, because fashion never takes the long view. It’s always looking at the next season. Maybe the pandemic will change that, but I’ve often imagined how all this will look to an audience in 50 or 100 years. I thin people will look at Sex Clown as a performance and they will be amazed by it. They won’t understand why it happened then, but they will be triggered by it.

It was also a small collection and there aren’t many photographs. Also, most of the pieces were split over four museums, so they are not available for shoots.

Do you feel inclined to revisit it?

No, I don’t think so. It was such a particular energy, and the way it was presented… No, it was a bit like a holy moment for me, and it should keep that feeling.

It’s been 40 years since Walter graduated from fashion college. I’ve been thinking about all the designers who are hitting that landmark: Dries, Michael Kors, Marc Jacobs. It’s not like you go into fashion thinking, ‘This is what I’m going to be doing in my sixties.’ Music’s the same. Mick Jagger’s 77, for heaven’s sake, but life’s what happens when you’re busy making other plans, as Jagger’s late contemporary John Lennon so sagely observed. So what stays? There’s something about the Van Beirendonck signature that suggests it will linger. It has enough chaos that it offers no easy answers, enough colour that it appeals to a sense of play. It’s atavistic and scifi at the same time. There’s a ritualistic, pagan spirit. It’s supremely cult – and occult. Like the ‘Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family’ (because Walter needs a Bowie reference and I do, too).

What do you think history will make of you?

I don’t know, but when I look at Rudi Gernreich, for example, the kind of people I admire so much because they were working so hard on their ideas and they had so little recognition during their lifetimes – but then they leave such an incredible legacy… I hope that I will also leave a legacy that will be inspiring for future generations.

Do you think of all your students from the Royal Academy over the years as a living legacy in a way? There are all these children of W.&L.T. in the world, like Craig Green and Bernhard Willhelm.

Well, they weren’t exactly students, but I think what I learned is that you can do a lot, almost the impossible, with very little. You don’t need a lot of infrastructure and money to do incredible things. Alex Wolfe is another one who is starting to become quite big now; he was one of my interns. For all these people to see me work – and, first of all, I do all the work myself; I am really there A to Z in the whole collection – and to see the possibilities even with such a small team, how it’s still possible to achieve rather impressive results… I think that impressed these designers, and gave them a lot of energy and dynamism to go ahead. But legacy is such a difficult thing to talk about.

It’s something that other people talk about on your behalf, but I mean, when you project forward to 2050, when there will no longer be the acolytes in the here and now, there will still be your sort of enduring philosophy – freedom, tolerance, challenge. Think about sci-fi. Someone should write a book where W.&L.T. becomes a new religion of the future. Wouldn’t that be fabulous?

The nice thing is that I am thinking that way, about 2050. During an archive shoot, like the one for this magazine, with all those pieces from 30 years ago until now, they still feel that they belong to the same universe and the same designer. And that makes me very happy and proud that I have a very recognizable signature that you can read from a distance. That is also a bit of a legacy – that you are recognizable and that your work is complete.

Are you a hopeless romantic?

Yes. I am very romantic. I love to listen to romantic music – I just bought the new one from Lana Del Rey – and I love to fall in love.

Who or what do you fall in love with?

People that I am attracted to and who I feel are interesting. It doesn’t happen every week, but maybe every 10 years there is somebody I think is more interesting than the other people I am meeting. So that is a feeling of becoming friends or talking about things and I enjoy that.

What are you going to do with the rest of the day? Now we are going to have lunch, downstairs; I don’t know what it is, of course. Then we’ll go for a walk, at least 7,000 steps, and then after the walk we will go to buy food in an organic farm that sells fruit and vegetables. And then I will come back and continue with my fabrics. At the moment I am ordering the fabrics for the new summer collection.

Walter and Dirk enjoyed a goat’s cheese quiche for lunch.