The transformation of China, the rise of SKP, and the story of Mr Ji.

Interviews by Jonathan Wingfield

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Creative partner: Dovile Drizyte

The transformation of China, the rise of SKP, and the story of Mr Ji.

In February this year, it was reported that SKP Beijing had become the highest-performing luxury department store in the world, overtaking longtime leader Harrods. While SKP is still relatively unknown to consumers outside of China, for many in the industry the news represents the latest stage in a broader shift in global luxury fashion, one being further exacerbated by Covid-19. China’s ever-growing consumer appetite and purchasing power (both pre- and post-Covid) is sustaining the profitability of many Western brands, and increasingly influencing their strategic and creative decisions.

SKP launched its first store, located in Beijing’s Central Business District, in 2007. The project of Mr Ji – as its founder and chairman, Ji Xiao An is better known – SKP Beijing currently stocks more than 1,100 brands (of which more than 90% are international), and in 2020, had sales of 17.7 billion renminbi (€2.27 billion). All were made in the physical store – SKP has yet to develop e-commerce. Beyond the store’s luxury mall-like appearance and gigantism (its floor space is equivalent to 25 football pitches), SKP has also become a key strategic partner for many Western brands navigating the myriad specificities of the Chinese market in their quest for more consumer hype, devotion and sales.

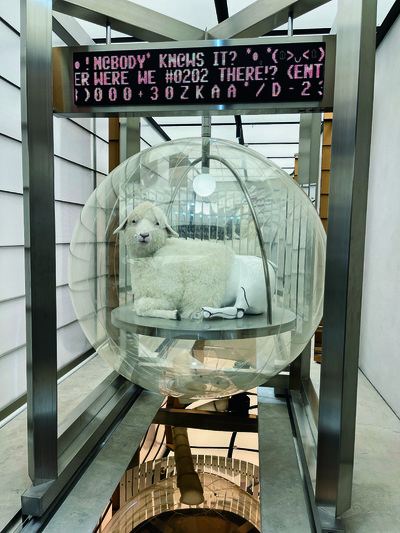

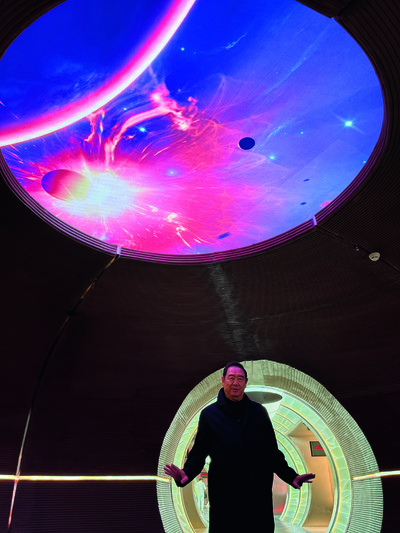

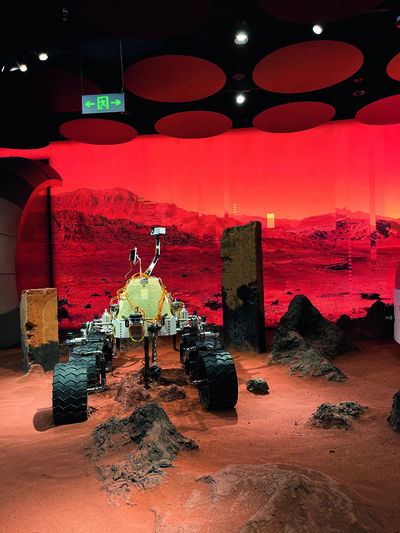

Just before the pandemic hit China, Mr Ji launched a younger, edgier store, SKP-S. Located across the road from SKP Beijing and designed in collaboration with South Korean eyewear disruptors Gentle Monster, it takes the existing luxury retail concept and transforms it into an otherworldy hyper-sensorial experience. Within SKP-S’s four storeys, a mix of high-end streetwear and luxury brands including Prada, Sacai and Gucci are accessed via Kubrick-esque LED corridors, replica lunar landscapes, and a theatrical farmyard in which robotic sheep ‘graze’. This is department store meets daka, the attention-grabbing Chinese culture of using social media to show off the people, places and products you experience IRL.

Beyond its playground of click bait, however, SKP-S has a dynamic recipe for success: a carefully curated selection of all the right brands, including many that provide limited-edition SKP-only products, presented within a spectacle-heavy ancillary world in which culture and commerce collide. Indeed, a key feature of SKP-S is T-10, a cultural space on the top floor, that in the forthcoming year will stage exhibitions including a Valentino show curated by Pierpaolo Piccioli, a Juergen Teller solo show, and Style in Revolt, the world’s most comprehensive survey of streetwear to date.

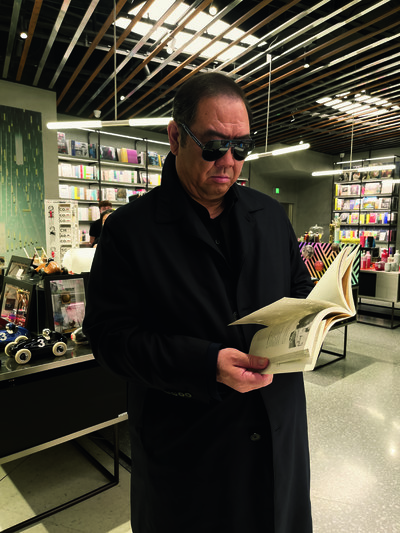

Eager to delve a little deeper, System has spent the past six months exploring the world of SKP. Given this is the first time Mr Ji has agreed to be interviewed, we took full advantage and also invited Patrizio Bertelli, CEO of Prada, and Jonathan Anderson, creative director of Loewe and JWAnderson, to record conversations with him, before Mr Ji led photographer Juergen Teller on a personal guided tour (remotely, of course) of SKP-S – sheep, robots and all.

What emerges over the following pages is the sense that in SKP’s blurring of physical and digital, cultural and commercial, local and global, Chinese and Western, lies the template for the future of luxury retail.

‘When I was young, I had many

dreams, but running a retail business

was never one of them.’

Mr Ji in conversation.

25 January 2021.

Part I

The rise of SKP

Jonathan Wingfield: Could you start by telling me about some of your retail experiences prior to launching SKP?

Mr Ji: I started in business with retail and I’ve never done anything else. I’ve always been interested in opening different types of retail – department stores, shopping centres, supermarkets, restaurants – which is what I’ve done.

You entered luxury fashion retail in 2007. What was the landscape for this sector in China like around that time?

China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, which was a watershed in the country’s fashion and luxury industry. According to the rules of WTO entry, luxury brands were able to open direct retail stores in China legally, and so many international brands from Europe and other markets began to expand their retail distribution in the Chinese market. At that time, the best-known luxury retail venues in China were Plaza 66 in Shanghai and China World Mall in Beijing; they were the two places with the highest number of luxury brands. The brands then started to open their own direct retail stores, predominantly in shopping malls.

What led you to believe luxury fashion represented a strong opportunity?

After 2008, in the midst of the global subprime crisis, the Chinese government implemented a 4 trillion renminbi economic stimulus plan, which pushed China’s economy onto a faster development track. Urban residents’ incomes increased significantly, especially after 2010, and the trend of rising consumption intensified. We sensed the huge potential and growth opportunities of China’s high-end consumer market. As a result, we became determined to make a fresh start with SKP. I had already hoped to build a high-quality fashion lifestyle destination in Beijing, but I decided to significantly upgrade the project’s positioning. We redefined the structure of all categories and brands, updated more than 60% of the product offerings, and reduced the overall number of brands by 40%. Although SKP had been operational for less than four years, we were still determined to completely update and upgrade the store’s standards. Not just a redecoration, but a complete revamp in all areas: from the mechanical and electrical systems, to its spatial layout and all audiovisual experiences. In short, we built a completely new store, as well as a completely new SKP brand.

How did you go about securing the presence of those international luxury fashion brands for the revamped SKP?

It was difficult at the beginning. In any business, if you want to make bold changes, you are bound to face big challenges. Thankfully, some important people anticipated that our concept would succeed: Michael Burke, CEO of Louis Vuitton, was among the first who came out to support me, as did Mr Pinault; Mr Bertelli also said that he had faith in me and appreciated the changes I was about to make. Most of the others took an attitude of half-belief and half-doubt, though, wondering whether we could actually create what I had in mind. My experience is that before people see the physical outcome of your work, there are always question marks. In the end, we won the trust, understanding and support of most brands. The key was to have patience, and I’m very grateful to all our partners for that.

How did you present the concept to the brands?

I wanted the brands to understand that SKP is a retailer, not a real-estate developer. At that time, both in Hong Kong and across the mainland, real estate developers were dominating the fashion and luxury business, creating a building, and then just leasing spaces to brands. Of course, that is a valid business model, but as a retailer, I’ve always understood retail differently. I think the fundamental driving force of retail growth comes from the customer experience. With this in mind, we hoped to establish a fashion-retail ecosystem based on a specific product category structure, while redefining the business model according to consumers’ shopping habits and requirements. Concretely, this meant that at SKP, we required each brand to open multiple in-store locations, each one based on a different product category. This was something most brands had never previously done in Asia and went against how they were used to operating. That presented a challenge to their management, even though this concept of fashion retail is simply more in line with shoppers’ habits. We hope to establish the SKP fashion ecosystem – with its own air, sunshine, lakes, streams, trees, grass, flowers, animals and warmth – in order to create ‘oxygen’ for the industry.

‘During the Cultural Revolution, young people yearned to wear green military uniforms and ride Phoenix bicycles to express a fashion language.’

You mentioned before that there was an upgrade in Chinese consumption patterns. What tangible evidence did you have to support this?

Living in Beijing, we feel impulses of change taking place in the world every day, through things we see and hear. We saw many Chinese travelling abroad – to the United States, to Europe – and witnessed crowds of Chinese customers shopping in Paris. This kind of insight doesn’t always require specific supporting data. Financial figures are just the surface of the ocean; the broader trends of social development influence the overall ocean current, and this is what determines real change.

Was there a risk that the consumer experience of, say, shopping for a bag in Louis Vuitton’s flagship on the Champs-Élysées simply couldn’t be replicated locally in Beijing?

Shopping is part of everyone’s travel experience, but no one can travel and shop all the time, so consumers will inevitably return to their home cities and shops. In the 1980s and early 1990s, the Japanese were buying all over the world, and many returned home to shop. Then came the Koreans and the Chinese buying overseas. There are three factors that influence Chinese shoppers overseas. First, the unique fashion experience in Europe; second, buying fashion goods is a process that comes with a spiritual value of satisfaction; third, the price difference. These things change greatly over time. Prices will drop over time as we build up our own buying capability – working directly with the brands and without middlemen – and when tariffs decline as China further opens up. We have a genuine opportunity for SKP to serve Chinese customers better if we are then providing improved experiences in a better fashion ecosystem than in Europe.

Let’s talk about that price difference. It’s such an important aspect in the dynamic between Chinese consumers and luxury Western goods.

Price difference is an inevitable factor in the tourism market: there is always a certain price difference between the domestic and international market. This price strategy itself is a reasonable arrangement and is composed of three parts. First, the impact of import taxes; second, exchange-rate fluctuation; third, differences caused by non-tariff factors. Over the past decade, the price gap has generally been narrowing. First of all, China’s import tax has continued to decrease; second, many brands have adjusted their relevant policies and adopt a more reasonable ‘global pricing strategy’; third, companies such as SKP can now buy directly wholesale from brands. The price gap will continue to close in the future. Especially in the post-Covid-19 era, more consumers will spend more money in their home cities. Of course, many Chinese people will resume travelling after the pandemic, but we may not be able to return to what it was before the pandemic.

Import tax has been decreasing, while brands will be giving wholesale discounts because of the volume of products being bought by a company like SKP. So is there a possibility that those prices could drop to the same level as in brands’ home territories, or even less?

At present, our wholesale business does not have big enough a volume, even though we have more than 500 brands from whom we buy wholesale directly in Europe. At SKP the main key performance indicator for buyers has always been the sell-through rate, though: we want to ensure we buy merchandise that our customers want to buy, rather than just pursue large-scale wholesale purchasing. Moving forward, we’re looking into how we can collaborate more closely with brands to create exclusive products for SKP, including co-branding. The differentiation of our products is the most important thing for us.

SKP’s post-2011 upgrade was taking place while social media was really starting to gain momentum. To what extent was SKP as a digital experience part of your thinking at the time?

In China, everything happens so fast, and from 2000 onwards, we already felt the changes that were about to happen. Digital technology is, of course, the great advance in modern-day human society, and has completely transformed human communication, knowledge and information transmission. Nonetheless, I think that no matter how developed digital channels are, it is difficult to substitute the experience and emotion one gets in a physical space.

‘I had the opportunity to attend university. Before that I was a farmer, I joined the army, and I worked in factories. These were all precious experiences’

Did the rise of Net-a-Porter and more general shifts towards direct-to-consumer brand operations make you nervous about your physical-first strategy?

I remember Macy’s starting to make large-scale digital investments after 2000. My friend Terry Lundgren [Macy’s CEO at the time] told me they hired more than 200 experts, established offices in New York, and allocated huge budgets. Online business was growing fast; they were a pioneer in omni-channel, and had a great impact on the industry. Yet I always felt that their transformation had not been clearly thought out. You have to think about the connections between the online business and your existing business, and the contradictions and conflicts that might arise between them. It’s not just about how much your online business grows, but also whether your overall sales are growing. If you just move your offline business online, is that growth actually healthy? Of course, there is no absolute distinction between online and offline in this society, and although SKP does not currently engage in direct online transactions, we obviously use many digital tools.

The point is not whether you do online transactions, but how you do them and whether they offer an experience consistent with SKP’s standards. I believe it will be figured out one day, but in the meantime we are focused on improving SKP by doing what we are good at first.

You mentioned Macy’s. I’m curious to get your thoughts on the current state of the US department-store industry.

There are still good department stores in the US, such as Nordstrom. Some others have problems, but each situation is unique. The reasons for this are often complex, but one of the fundamental reasons is that they are no longer willing to change the experience of their physical stores. It feels like they have given up on innovation for their existing businesses. They have invested too much money in digital sales. The deeper problem is that there are simply too many shopping malls and department stores in the United States and they all have similar offerings. I should add that I haven’t studied the retail industry in the US in depth, so this is just my gut feeling. Fundamentally, there is a problem with the structure of supply and demand. With online commerce joining the game and taking a chunk of the share, the bricks-and-mortar market is in trouble – supply is now far larger than demand.

Historically, Western brands would be offered favourable rents by Chinese mall owners to entice them to their malls. Has that dynamic now shifted?

Under normal circumstances, leading brands have a greater say, but the key to the decision is about creating value for both parties. I pay more attention to how to establish a more benign interactive and cooperative relationship. SKP is not a real-estate developer that just collects rents, and we also don’t want to be just a retailer. We wish to become a broader and more active participant in the fashion industry. I think the relationship between a retailer and a brand should be a collaboration based on mutual understanding, trust and support. Of course, there will be discussions on the balance of interests between SKP and brands. However, what matters is the value creation of joint cooperation – how to make the cake bigger for everyone.

Can you give me an example of the conversations that you have with the business leaders in Europe like Mr Pinault, Mr Arnault or Mr Bertelli? My understanding is that you are able to influence Europeans to be more innovative.

Cooperation is a long-term process. It is impossible for any brand to enjoy a high growth rate all the time; business performance will always fluctuate. At SKP, brands that perform well deserve respect, of course, but when a brand faces difficulties, I prefer to go to Europe and meet the CEO to tell them what I have seen, and analyse how to make the business take off again. It’s more about communication. My job is to help partners do business correctly in the Chinese market, while protecting the SKP ecosystem. All brands hope to have larger retail space in SKP. Even if this cannot be fulfilled, we won’t simply refuse, but rather work to find a feasible solution.

Let’s talk about SKP-S and the ways this edgier store engages with a new generation of Chinese consumers.

SKP-S is another bold venture anchored in the concept of innovation. As you know, innovations tend to be driven by fringe forces. Over the past six or seven years, we have noticed that some streetfashion brands have been expressing rebellious, bold views, with an attitude towards fashion that uses a completely different vernacular. By doing this, they attract a younger generation who love what they stand for and are willing to buy their products at high prices. For many years I have been hoping to build a store that presents street-fashion culture in a completely different manner and context to anything we’ve done before. The challenge has been how to demonstrate the power of street fashion in new and exciting ways, while adhering to the consistency of SKP’s overall positioning. We have been inspired by artistic and technological elements, as well as the concept of collaborations, and I was lucky to find excellent partners with whom to realize these ideas. Ultimately, the aim of SKP-S was to create a unique space of social experience for the younger generation, and it has worked: it not only attracts a younger customer base, but has also become a daka [‘must-see’] destination that they visit frequently.

‘I looked up to Walmart stores and Kmart hypermarkets in the US, and would ask myself how could someone grow such a large-scale business?’

This idea of daka feels entrenched in the SKP-S concept. The spaces throughout SKP-S that you have orchestrated with creative collaborators such as Gentle Monster, Sybarite, United Visual Artists and Weirdcore take shopping into the realm of the spectacular.

Building the concept of SKP-S was a deeply creative process, one that was developed in a free state and steeped in subjective judgement and awareness. I didn’t deliberately think about who I wanted to please; it’s more a question of conjuring up the most dream-like place for the market and the customers. As long as you firmly believe in your feelings, and you have a clear picture of them in your mind, you should go all out to make every detail perfect.

In SKP-S, integrating the core shopping experience into a cultural world is key. You’ve added T-10, a cultural space on the store’s fourth floor that has a world-class exhibition programme. Why do Chinese customers find these cultural moments appealing and important?

Cultural experiences are always important parts of the SKP ecosystem. At SKP RENDEZ-VOUS, we host many art exhibitions and book launches, with an emphasis on the interaction between famous Chinese artists or writers and our customers. T-10 is a more radical concept: a space of 4,000 square metres, in which visual artists, streetwear creatives and fashion brands can perform a variety of repertoires.

SKP has its roots in Beijing, but do you have plans for it beyond the city?

We opened SKP Xi’an in 2018, which is a very high-quality project. In 2020, sales there increased by 37%. In the next three to five years, SKP will open in Chengdu and Wuhan, two of the most important cities in China, each with a population over 10 million, and with huge market potential. These projects will be approximately the scale of SKP Beijing, but always within our philosophy of disciplined growth and quality expansion, requiring time and patience.

Part II

The (r)evolution of

the Chinese consumer

I wanted to look into China’s recent past to better understand how contemporary Chinese consider and relate to buying fashion and shopping. What are your own thoughts on how people perceived fashion in the past?

China is a country that has a nearly 5,000-year-old civilization. If you understand China’s culture and history, you see that there is an extremely deep fashion DNA in Chinese cultural genes. Of course, in different times, there are different ways of understanding and pursuing fashion culture. There is a very famous novel, A Dream of Red Mansions, which contains detailed descriptions of the pursuit and enjoyment of the exquisite fashion, culture, and art in the 18th century. In the 1930s, during the Republic of China in Shanghai, there were many films, dramas and literary works that showed the fashion trend of consumerism at that time.

Even in the era of the Cultural Revolution, young people yearned to be able to wear green military uniforms and ride Phoenix bicycles to express a fashion language of the revolutionary era. For young people today in China, fashion consumption is a natural evolution in their lives when they become better off. The Chinese are willing to accept new things and understand fashion. They learn quickly and imitate well. The Chinese fashion consumer culture has already shown huge growth over the past decade, and the underlying logic of that has been driven by Chinese cultural values. Income has risen, and the desire for a better life has become the driving force behind a younger generation of Chinese consuming fashion.

‘Most of the luxury fashion brands took an attitude of half-belief and half-doubt, wondering whether we could actually create what I had in mind.’

You mention an ability to imitate. To what extent do you think China’s recent pursuit of fashion has been about emulating Western fashion?

First comes imitation, then comes a deeper understanding and personalized pursuit. Since the reforms and opening up, Western fashion culture has impacted upon Chinese consumers from all directions: Hollywood movies, film and television dramas became accessible in China; Chinese people began travelling to Europe and other places; numerous multinational companies entered China and with that came foreign company executives and their families. Their cultural tastes and attitudes towards fashion have inevitably had an impact on the mentality of the new generation of Chinese consumers. Louis Vuitton came to Beijing in the early 1990s and opened a small boutique in the Peninsula Hotel. It was a visionary move. China at the time was neither as rich nor as developed as it is today, but it was full of life and vitality. The controlled economy had been dismantled, and the new market system was still being established; market order had yet to be created.

Louis Vuitton showed vision, but also had great courage to take root in China at that moment in time. The brand’s success came not only from being one of the first luxury houses to enter the Chinese market, but also from its commitment to establishing huge brand awareness here.

In what ways did Chinese consumers understand and then reinterpret the Western notion of ‘luxury’?

The word ‘luxury’ for many Westerners usually implies exquisite craftsmanship and superior quality. The modern-day concept of ‘luxury’ in China is somewhat different though. Whether it’s lost in translation or the result of cultural differences, the notion of luxury is more about expensiveness, wastefulness and unnecessity. Many Chinese consumers have a very different understanding and appreciation of luxury goods. That’s why I prefer to call this industry ‘high-end fashion’, which is more consistent with the connotations of luxury fashion in Europe. Take for instance the art world: some artworks are very expensive, but Chinese don’t consider them luxury goods because an artwork is only precious for those who appreciate it; those who don’t won’t buy it, no matter what the price tag says. In my opinion, ready-to-wear clothing is fundamentally about necessity and self-expression; the image a person is trying to project to the world shows his or her inner pursuit. So we need to be careful about the misconception of the term luxury, which limits it to something unnecessary and wasteful, which is obviously far from the reality of consumer needs in the fashion industry.

Given China’s population, how do you balance quantity and quality?

Quality is always the number-one standard for SKP. Our requirements for quality far exceed quantity. Only by maintaining quality growth can the business be everlasting. The thing our industry needs to be most vigilant about is lack of patience. Excessive pursuit of short-term performance will damage long-term development of the industry. It’s hard for me to understand brands live-streaming fashion shows where customers can instantly buy items; it’s unbelievable. In my opinion, if brands hold six big shows a year, no matter how talented the designers, they’ll not be able to maintain their uniqueness and creativity for long. Running forward too fast will only make our industry lose its soul. Maintaining a proper balance between the pressure of commercial capital and fashion creativity is an art. It is also the foundation to ensuring that we create high-quality fashion value.

But isn’t this at odds with the digital culture of immediacy?

Luxury fashion is not ‘fast-food’. For the price customers pay for your brand and products, they have to be buying the highest quality ideas, the highest quality products, the highest quality experience, and the highest quality service.

How do you introduce these high-quality values to younger customers?

There is no future without young customers and I consider SKP to be a high quality enterprise with a democratic attitude towards consumption. I want to build an elegant environment of undifferentiated service. You can have something to drink, buy a book, meet friends or just hang out. In fact, many of our best customers began shopping at SKP by buying a lipstick or a cup of coffee. As their career progresses, so their shopping habits within SKP also evolve.

‘There are simply too many malls and department stores in the United States and they all have similar offerings – supply is now far larger than demand.’

Part III

The founder’s story

To what extent did your parents and family life impact your later life as an entrepreneur?

I grew up in a very ordinary Chinese family. My parents were kind, simple and compassionate, tolerant and equal, and attached importance to their children’s education and the development of their personalities. My mother has excellent taste and intuition, being self-disciplined and frank. I think I inherited some of her qualities and they live on in the SKP ecosystem.

Were you a grade-A student or rebel?

I liked being an 80% student, rather than being straight A. The reason I didn’t want the other 20% was that I still wished to have time for myself to read, hang out and play basketball. My talent was finding a balance between rebellion and academic excellence. Later, I realized my temperament was suited to pursuing freedom in my life, without attracting attention. If you were rebellious, people would want to get you into trouble; if you were the top student, you’d feel pressure from your peers. So the best tactic was to lower your ranking and allow yourself more free time and space. My personal wisdom is to avoid trouble or direct confrontation.

Was university an option at that time?

It was only after Deng Xiaoping restored the college entrance examination system that I had the opportunity to attend university. Before that I was a farmer, I joined the army, and I worked in factories. These were all very precious experiences.

How did those experiences influence your vision and leadership of SKP?

The biggest takeaways were an understanding of human nature and society, and being grateful for what you experience. I decided in the early 1990s to found my own business, even though I had zero experience in operating and managing a company. I made many mistakes, but learned not to lose myself in them. As an entrepreneur, the most important thing is to have dreams and passions. You need to work hard and persevere. And you also need some good luck. I was lucky to be a Chinese person in the era of economic reform and the opening up of the country. When I was young, I had many dreams, but running a retail business was never one of them.

What dreams did you have?

When I was very young, I dreamt of being a scientist, a writer or a soldier – but I never wanted to be an entrepreneur.

What led you to pursue the unknown of entrepreneurialism?

Such a major life decision was not made on impulse, but through careful choices. Having the courage to get out of your comfort zone is the first step in starting a business. I didn’t know how to do it, but everything can be learned, and I liked the fashion industry.

How has your own understanding of fashion developed over the years?

In my memory and in my personal view, the strength of your artistic sensibility determines your understanding of fashion. My generation went through a period when Chinese society was undergoing tremendous changes – from closed doors to opening up, from a centrally planned economy to the market system, from one single ideological education to multiple cultural perspectives, and from poverty to wealth. Witnessing the transition from the most poverty-stricken and arduous times to the most beautiful times, we’ve experienced a huge contrast. As a result, my understanding of Western fashion culture has changed with the times and environment. But the real leap in my understanding of fashion has been acquired through the practice of managing SKP.

Were you travelling internationally at this point, and if so were there retail businesses that inspired you?

I saw a lot in foreign countries and had a lot of inspiration. In the US, Walmart stores and Kmart hypermarkets were everywhere, and I was very impressed by Macy’s and Saks Fifth Avenue. I looked up to those businesses and would ask myself how could someone grow such a large-scale business? The choices I made when starting the business were principally based on instinct. I might have entered the retail industry by accident, but I quickly discovered that I really liked it. So it’s been what I’ve been doing ever since. Although the Chinese market has been full of all kinds of temptations and opportunities over the past decades, I’m the kind of person who likes to focus on one thing and do that thing as well as I can.

‘In 10 years’ time, ‘Made in China’

will be synonymous with high quality.’

Mr Ji and Patrizio Bertelli

in conversation, 12 March 2021.

Moderated by Jonathan Wingfield.

Jonathan Wingfield: Mr Bertelli, when did you first visit China, and to what extent did you sense the scale of commercial opportunity at the time?

Mr Bertelli: The first time was in 1993. I visited what was then called Canton, then Shanghai and Beijing. I remember the impressive sight of all the people riding their bicycles in Tiananmen Square. I was immensely curious, and my first impression of China was a feeling that this huge population was about to undergo a considerable change in their habits and their way of life. It was pretty clear that China would become the market it is today, once it started tackling the social differences within its huge population. At the time, few people had access to – I wouldn’t call it consumerism – but to all those goods that make life easier and more pleasurable: a house, a car, a TV, all those amenities that we are all used to.

Could you talk about bringing Prada into China? What conversations did you have to have with local Chinese partners to make this a reality?

Mr Bertelli: Working with partners like Mr Ji has been absolutely instrumental in making ourselves understood. He was one of the first people in the Chinese market who truly understood luxury. I remember the opening of SKP in Xi’an – the Terracotta Army city – and the party Mr Ji threw for the grand opening: it was a clear expression of how he could take our concept of luxury in Europe and successfully implement it in the Chinese market. He is not the only one, but he is the best embodiment of this attitude towards luxury. It’s not so much a question of consumerism; it’s more a new attitude and new way of living in a country that couldn’t possibly stay as it was in the 1980s. It is a clear symbol of change. Over the past 30 years, China has been like a sponge, absorbing everything that comes its way. They’ve made things like luxury, consumerism and technology their own – and will continue to do so.

Did you also envisage the potential desire, enthusiasm and respect that Chinese consumers would have for the notion of ‘Made in Italy’?

Mr Bertelli: Yes, I sensed that immediately, for the simple reason that what we call ‘Made in Italy’ is a reservoir of know-how and crafts and skills that are simply not available in other countries. It is like champagne being unique to a specific region in France. Made in Italy is made here; it is in our DNA.

Mr Ji, what were your earliest experiences of connecting with Western luxury fashion houses?

Mr Ji: Over the years I’ve had the privilege of meeting and becoming friends with the owners and CEOs of many of the luxury fashion department stores and brands, and I have learned a lot from them. I have specific memories of meeting Mr Bertelli for the first time: I remember being in his office and him telling me about the history of Prada, its present status, and his vision for the brand’s future. I clearly remember Mr Bertelli explaining that while Prada is an Italian brand, born in Italy, it is also an Asian brand. He told me about attending a conference in Florence in the 1980s at which the chairman of Sogo, the Japanese department store, was giving a speech, and being invited to visit Japan afterwards. He told me that everything about Prada today as an international brand stemmed from that visit to Japan.

Mr Bertelli: Do you remember I did a lot of drawings while you were there?

Mr Ji: Yes, I recall you drawing a chart, illustrating the fact that since 1991, Prada’s business growth has been amazing, and that its international growth also stemmed from that moment. You also told me that one day the Prada IPO would take place in Hong Kong.

Mr Bertelli: I have always told you everything, Mr Ji, including that the IPO would happen in Asia. Mr Ji is an excellent man; he is very strict and severe and demanding, but in good ways. Ultimately, Mr Ji, I want you to know that if Prada has the status it now enjoys in China, it is thanks to your work and your time.

Mr Ji: I am grateful that my interaction with Mr Bertelli has always been frank and to the point, because I have learned a lot from those conversations.

Mr Bertelli: Let me explain something about Mr Ji: his greatest gift is his perfect sense of timing. Although his process can be relatively slow, it is always carefully thought out and planned throughout. And he always reaches the objectives that he has in mind.

‘Mr Ji is like an elephant, and it’s much better to avoid a clash with him because you could get crushed if you go against him.’

Mr Bertelli, you say Mr Ji is strict and severe in a positive way. Could you give me an example of this in your business relationship?

Mr Bertelli: When he speaks about business, Mr Ji makes his own opinions and comments known. He might say, ‘Why don’t you do this or that? Why don’t you consider other options?’ But really, as soon as either of us suggests something, he expects it done. It is not necessarily a discussion; it is more like a proposal and I have to deliver what I’ve promised. He is like an elephant, and it’s much better to avoid a clash with him because you could get crushed if you go against him.

In what specific ways does Mr Ji represent a strategic partner for Prada in its rapport with the Chinese market?

Mr Bertelli: I don’t know how he does it – maybe it’s purely instinct – but he has such a profound understanding of the quality of Prada, and in particular an appreciation of when a product is just right. The other thing is his extraordinary ability to look ahead and foresee the future. That gives him the insight to find the best architect for his stores, to have the best product merchandisers, and so on. In this respect, he is not European at all.

What about pure business projections?

Mr Bertelli: It’s simple – the first rule for Mr Ji is to respect the brands. He is not about making quick easy cash; he doesn’t want to depreciate his capital or his assets. He doesn’t like to do end-of-season sales; he wouldn’t want to cheapen Prada like that. He protects the capital that he invests in major brands. He is the best defender of his market and our brands. Of course, he is not the only one: Isetan does the same in Japan, as does Lotte in Korea – and I don’t want to downplay the importance of other players in the Chinese market – but I have to say that SKP is the real champion in the Chinese market.

How do the differences between Western and Chinese consumers shape the ways Prada operates in China?

Mr Bertelli: It’s more relevant to look at generational rather than geographical differences. If you consider Gen Z, I don’t see much difference between Chinese and Europeans, whereas there is a vast difference between Chinese and European generations born in the 1960s and 1970s. For millennials and Gen Z, it is a more globally level playing field because people are using the same digital tools more or less. Chinese consumers were actually the first to adopt digital systems on a wide scale; they were even faster than the Japanese. Just think of payment systems: China is totally cashless now, even in the smallest market in a tiny town, you pay with your phone. In Italy, we are still far from that; it is still not that common to use a credit card, while paying with your phone is out of this world. Even the platforms in China are different and much more active and quicker. It is our job to get up to Chinese speed.

Mr Ji describes SKP-S as more visual feast than just a shopping experience. What do you think of this evolution of shopping as cultural experience?

Mr Bertelli: Mr Ji understood perfectly that he couldn’t just open boutiques. He had to present an entirely new concept, with restaurants, bars, spectacle and entertainment at the core. The key thing is that the quality of experience is always maintained. One thing I want to tell you, Mr Ji. I know you don’t particularly care for it, but you should open SKP in Shanghai. I tell you every time we meet, but you never listen to me.

Mr Ji: We have so many opportunities in China; it is not only about Shanghai.

Mr Bertelli: Come on, Mr Ji! Shanghai is a symbol, a name; it is the most international city you have, akin to Los Angeles or New York. It is a global city. So listen to Patrizio and open in Shanghai!

Mr Ji: I certainly don’t deny Shanghai’s market position, but we need to be patient and make the right decision instead of just expanding for the sake of expansion. China is not just Shanghai; there are many other beautiful cities.

Mr Bertelli, you’re being the elephant now.

Mr Ji: Now you have a proper insider discussion, Jonathan, not just an interview. You’ve got proposals coming from either side, just like the private meetings Mr Bertelli and I always have. In terms of SKP-S, Prada has without any doubt been the role model in all aspects. That is because Mr Bertelli truly understood the objectives of SKP-S; he understood the importance of connecting with the next generation of customers. So I must say this to Mr Bertelli: so many young customers instantly fell in love with the Prada store in SKP-S, and not just with the product or with the visual merchandising. They loved everything in the store!

‘Even in the smallest market in a tiny Chinese town, you pay with your phone. Whereas in Italy, it is still not that common to use even a credit card.’

Mr Bertelli: I knew from the beginning that SKP-S would need to be a retail offering that would change three or four times a year, and that it would need to be a physical representation of what young customers see in the digital world. That is the core of the strategy – a physical experience and location that changes almost as frequently as a digital one.

Mr Ji: We rotate a few times each year, but it isn’t just rotations for the sake of rotations; it is the stories, themes and message that you create while making those rotations. Some brands rotate their products and their physical space two or three times a year, but what they are offering actually leaves the customers underwhelmed and disappointed. Many of the creative directors in Europe ignore the fact that SKPS is a very important platform, one they should really engage with more to create a deep connection with young Chinese customers.

Mr Bertelli: The idea is that every time you have a rotation, you need to accompany it with something really special and unique.

Mr Ji: Some other brands just don’t have this clarity of vision.

Mr Bertelli: Having a vision means you need a lot of people to develop it, which is expensive, and lots of brands just play safe with their money.

Mr Bertelli, what about the challenge of keeping up with the pace and the requirements of SKP? How do you reconcile the time, expertise and resources required to deliver Prada quality with the sheer scale of the Chinese market?

Mr Bertelli: That’s really the heart of the matter. It’s certainly not easy, but I can try to explain how we proceed. We don’t rely on an external creative studio, so as soon as we start designing and creating our products, we know the problems we will have to solve. Nothing happens in isolation; everyone is involved with their skill sets and capacities from the very beginning. From an outsider’s perspective this might sound messy, but it is the only way to really come up to speed with the whole process. Inside Prada, there are maybe 50 different people across multiple departments perfectly aligned with what SKPS means and what it requires – store furnishings, fixtures, products, photography, campaigns. We’re currently working on a beautiful SKP project for late April based on the idea of camping. I love the project; it is going to be very successful.

Mr Ji: I’ve seen it and I love it, too.

Mr Bertelli: The camping project will continue throughout the year and we’ll provide different products for each season. It is almost like a movie that will go on for eight months, chaotic but very interesting. We’re designing it like the script for a movie, changing things and rearranging them as we go along, and we will keep fine-tuning them throughout the duration of the project. We want to include some kind of ‘living pictures’, with real people interacting with the presentation. The effect we want is like when you walk past a film shoot.

Mr Bertelli, how do you feel about SKP’s strategy of focusing on physical retail, while not yet developing e-commerce? It feels almost counter-intuitive to modern life but has been one of the fundamental reasons of its success.

Mr Bertelli: That would be my choice and my attitude, too. The reality is that Mr Ji made this decision and the results are what we see; he is absolutely right. Of course, Mr Ji is always free to decide to increase his presence on e-commerce platforms at any given time in the future. All the products we do for SKP are exclusive; they’re not available anywhere else on the retail market or on e-commerce platforms. It is SKP’s own exclusive product.

Mr Ji, could you tell me a bit more about the strategy of exclusive products? How many brands provide exclusive products and what percentage of their overall stock is exclusive?

Mr Ji: It depends on each individual brand’s strategy, their own broader ambitions for the Chinese market, and their own judgements about SKP. Let’s continue to take Prada as an example: Mr Bertelli and the Prada company have clearly come to the conclusion that if you make that investment in SKP – with exclusive products and collections – you will get better returns. There are other brands that want to do similar things, although some may not have the skills, financial resources or infrastructure to achieve this level of ambition. What I can say with certainty is that no other company currently has 50 people with such a good understanding of how SKP works, and no other company has leadership as strong as that of Mr Bertelli. As Mr Bertelli said, it is not a question of isolated work – it requires an entire system.

‘All the Prada products we do for SKP are entirely exclusive; they’re not available anywhere else on the retail market or on e-commerce platforms.’

Mr Bertelli: It takes leadership, yes. At Prada, we really want to be able to do things that no one else does; my wife, Miuccia Prada, and I both feel the same about this.

Mr Ji: Always embrace the dream. Without it, it would not have been possible.

Mr Bertelli: You are like my alter ego in China.

How important is it for Prada’s creative leaders – Mrs Prada and Raf Simons – to visit somewhere like SKP? The tangible connection between creator and consumer feels increasingly important.

Mr Bertelli: The power of the brand is not sufficient; we firmly believe in direct contact. I have visited China countless times over the past 30 years. Miuccia was there back in the 1970s when it was practically closed; she travelled around by train for a month. Fashion designers who lock themselves in an ivory tower are just too far removed from reality. Of course, in the past year we have all been relying on digital communication, which is useful but not enough. It takes away so much personality from our connection to the world. You learn so much more by walking around a street market than by reading reports. Taking a train, walking around the streets, observing people, going to popular restaurants, that is how we learn.

You alluded to the pandemic. Let’s discuss the impact and changes that Covid has forced upon the fashion industry.

Mr Ji: We cannot underestimate the impact Covid-19 has had on the human race, not just fashion. For our industry in particular, any business dependent on travellers or tourists is experiencing a lot of challenges, so at SKP we have needed to focus more on the needs of local customers. We need to look into how to improve the offerings in each of our local markets, to enhance the customer experience. Any improvements in a store’s physical experience enhance brand perception and that should not be underestimated. Perhaps the most important thing is that the whole human race is in the same boat, so we have to be united. There needs to be more communication, more understanding, and more mutual respect and trust. That’s the only way to meet the challenges of the future. SKP has to create closer connections, more collaborations, and a deeper sense of partnership with brands. These things will enable us to overcome future difficulties.

Mr Bertelli: The global pandemic has highlighted two fundamental things, at least as far as Europe is concerned. In our industry, brands cannot thrive by just selling to Asian tourists in Europe; we also need to focus on our own local customers in Europe and Mr Ji has said the same thing needs to happen in China. I agree that we need to be absolutely respectful of each other, not make any distinctions between different countries, and respect the Chinese market. When the pandemic closed the border Chinese customers had to shop far more at home. In this past year Chinese consumers have understood, I’m sure, that they can buy all brands in China, perhaps better than in Europe. The European market may not go back to the same volumes as pre-pandemic, that is not certain. We will need to evolve in terms of products, identity, communication. We need to follow the cultural changes in countries and new generations. Chinese 20-year-olds today are totally different to Chinese 20-yearolds from two or three decades ago; these customers today are totally aware of our products and our market. We need to work in sync with the countries where we operate and the customers we serve. In the past, it made sense to have the same product everywhere in the world, but the big growth areas

have been in tropical areas, equatorial areas, where temperatures are totally different to the markets we used to serve. Look at the climatic differences between Beijing and Hong Kong. We have to cater for different climatic and physical needs, and not just cultural differences, with products that have to convey the brand’s identity. Sometimes clients are criticized for being too demanding, but they know their products; they’re demanding for a reason. What really changed the market was the iPhone and the iPad hitting the market in 2009 and 2010; that brought about a huge change in our habits. Our approach to the market has had to change radically, not only with the products, but also with the way we present them on the market.

‘China will have to shed its identity as a big-volume producer and once it does that, it will become the owner of quality.’

How do you envisage the evolution of the Chinese market, and what effects will this have on global fashion?

Mr Ji: The next decade in China is going to be key, because it is the first decade in the next stage of China’s economic development. We just finished the parliamentary sessions today in China, which created a five-year plan of national economic development focused on developing quality. The fashion industry in my opinion will grow at least three-fold in the next decade. More and more young people will embrace the industry. We need to create products, systems and structures that win the respect of these new generations. The demand for and the needs of the fashion industry in China are going to be huge, and the market will become more and more challenging. Like Mr Bertelli just said, Chinese 20-year-olds are so much more knowledgeable than 20-year-olds in China 30 years ago. They are far more demanding, and will make their own decisions about which brands they’ll continue to embrace and which they’ll abandon. They will make their own decision about which department stores they want to go to and which ones they will ignore. So the whole industry will become even more fiercely competitive. In the next decade, leading brands will become stronger, while the brands at the bottom will find it increasingly difficult. We have to set the bar really high for ourselves. We need to be agile and more flexible and active in terms of innovations. We have to do all of this in order to embrace the future.

Mr Bertelli: I agree entirely with Mr Ji. I was reflecting on the complexity of the market; it is going to become really selective and demanding. I am comfortable with that situation. I am 75 years old; I am not sure I will live until I am 85. I will leave the responsibility of guiding my son on this journey in the hands of Mr Ji.

Mr Ji, you just mentioned the parliamentary discussions about quality. We talked earlier about the value of the ‘Made in Italy’ label; do you think in the future that the ‘Made in China’ label could become a leading global symbol of quality?

Mr Ji: Producing a high-quality product is not the same as creating a high-quality brand. This is quite a delicate situation in the fashion industry. The creativity in a brand involves much more than just production and manufacturing. In China, building a world-famous brand requires guidance from the international brands.

Mr Bertelli: I think Mr Ji is being overly cautious. Let me take an example. In 1960, the Japanese started working in the camera industry; Olympus, Nikon, Canon, everyone started making cameras. When I was a boy, I remember people said that Japanese cameras were not top quality; we were used to buying German or Swiss brands, the same for hi-fi audio. Now we take it for granted that top-quality cameras and hi-fi come from Japan. As far as technology is concerned, China is following in the same footsteps as Japan a few decades ago. Think of Volvo, which is now owned by a Chinese company and has made progress in quality. Its newest cars are just fantastic, especially the electric ones. China will have to shed its identity as a big-volume producer and once it does that, it will become the owner of quality. The same goes for hi-tech: in 10 years’ time, ‘Made in China’ will be a label synonymous with high quality. I am sure you agree with me.

Mr Ji: Yes, the development of higher quality is inevitable in China. We have to use as few resources as possible to create as much value as possible. High-quality manufacturing is not simply a question of products; it is also about protecting the environment. That is now a very clear government objective: we want to push economic development, but we should not sacrifice the environment in this pursuit. It is, of course, a very difficult task to accomplish. The term ‘high-quality development’ sets a high bar. We need to change people’s mentality; they need better schooling, better housing, a more dignified life. To create future infrastructure for the luxury fashion industry in China, we will need an excellent creative education system, with good role models who can pass on their expertise and knowledge. All these aspects are included in the socalled high-quality development, as is our service sector, and the retail industry, online and offline. Better experience, better offerings, better service are all essential elements. The future will see us become more integrated into the rest of the world; more Europeans might start coming to China to create brands. It will be very interesting over the next decade. If you were 30 years younger Mr Bertelli, you would probably have already come to China to start your business.

Mr Bertelli: Twenty years younger! Actually, if someone could guarantee that I would be as fit as I am now when I am at least 80, then I would come over and start my local business right now! I’d need a good partner though.

‘The Chinese fashion industry will grow at least three-fold in the next decade. We need to create products that win the respect of new generations.’

Given China’s economic and social development of the last 30 years, are you surprised not to see more Chinese luxury brands emerging?

Mr Bertelli: Yes, I’ve often thought about this, but I can’t give you a sensible answer. Mr Ji should answer this.

Mr Ji: I think this is a problem we come across in the process of knowledge accumulation. I firmly believe that China will produce a number of internationally recognized brands in the future, but it just won’t happen in the short term. It will take time. Secondly, the overall luxury fashion industry infrastructure in China is not sophisticated: we need more creatives, patternmakers, an entire support system. This system is well established in other industries in China, but for the fashion industry, the infrastructure is not yet in place. We need time to develop this. Regardless of the sector, you need to achieve global status to be a great brand. Prada is such a great brand loved by so many different customers in so many different regions and countries: Europeans and Asians, and Americans, too. It is about your creativity and your dedication to quality and the details in the craftsmanship. There is also, of course, the brand marketing. You need all of that in place to become a brand that has international prestige.

Could you imagine a time when a successful new global brand emerges that has no specific geographic or cultural provenance? Where location is no longer significant to success?

Mr Bertelli: It is highly unlikely to be a new brand, but Prada and other brands are looking at the global market. I agree with Mr Ji that we are understood globally, and not just in terms of luxury, but also in what we want to communicate. We communicate through products, as well as through lifestyle and the concepts we hold dear, such as art, the art foundation, the America’s Cup; everything we do. Prada is definitely trying to enhance the brand itself without necessarily always thinking we come from Italy. This is what we are trying to do, and it takes time for a big organization to do that.

Mr Bertelli, do you think there is an opportunity for Italian brands to transfer ‘Made in Italy’ skills at scale to somewhere like China? Can those skills be transferred out of their original context?

Mr Bertelli: I think that we could do it and we will have to do it. We shouldn’t be afraid of this or hold back. It is part of this overall global integration that we all require. We mustn’t consider people as opponents; we have to let globalization play out and eventually it will turn out to be positive for all.

Finally, Mr Bertelli, what have you learned from Mr Ji and SKP?

Mr Bertelli: First of all, and this has always been in my nature, is respect. I apply that to how we work together in a very open way without any double crossing or trickery. I trust Mr Ji personally a lot. It is very simple.

And Mr Ji, what have you learned from Mr Bertelli and Prada?

Mr Ji: Cultural respect, sufficient sharing and frank communication. More specifically, I’ve gained great insight into brands and the luxury industry from Mr Bertelli. I’ve learned how to lead and to manage a luxury brand. And in particular, I’ve learned to value the right attitude about details and product quality. Every time we meet, I learn so much. I know that we belong to the so-called older generation, but we need to keep challenging one another so we maintain our passion for our respective work. So many times Mr Bertelli has complained about the slow speed of my decision making, but every time we have achieved the shared target.

Mr Bertelli: No, you are not slow! You just reflect on things, and that is different. That is why I said you are like an elephant – but an elephant has a huge brain! I should add that I started my career aged 18, and I have learned a lot from many people. My advice would be to try and look for as many Mr Ji’s in your life as possible. I have been lucky to have had several along my career. My first partnership in Japan in the 1980s was with a distribution company called Miami, whose CEO, Kiichiro Funai, was very helpful. When I said I would like to start my own business in Japan, he had nothing against it and actually helped me. I can compare Mr Ji to the past CEO of Isetan in Japan; he was a dear friend. You need to look for the right partners, and most importantly, you have to be willing to listen to them.

Mr Ji: Thank you for your time and for your kind words.

‘You get to know your customer

in real life, not through a

spreadsheet.’

Mr Ji and Jonathan Anderson

in conversation, 19 February 2021.

Moderated by Jonathan Wingfield.

Jonathan Wingfield: Jonathan, you spent time in Beijing with Mr Ji at SKP, just prior to the pandemic. Tell me about that experience.

Jonathan Anderson: I was lucky enough to visit the new SKP-S store before it had opened or anyone had seen it. It was like entering a different planet! I’ll never forget walking in with Mr Ji and seeing a flock of robotic sheep that looked like they had landed on Mars, and then going upstairs to a restaurant where you could eat the cutlery. It was a whole shopping experience that I’d never previously had, and incredibly bizarre. I remember when I first moved to London, Dover Street Market had just opened and that was a thing, but this was like a whole other level, like going into a completely abstract place, which I thought was so interesting.

What did that experience tell you about the type of customer that SKPS looks to appeal to and engage with?

Jonathan: Mr Ji has put shopping at the forefront of experience. Where in the West we have previously explored the idea of conceptual shopping, this takes it into the art of the spectacular. It’s like going to see an attraction. It is incredibly new, in terms of what is happening in Asia. It’s the first truly conceptual department store.

Mr Ji, with SKP and SKP-S, did you want to take the retail experience to a level where the customer is in an immersive space that is a feast for all the senses?

Mr Ji: Street fashion has developed rapidly over the past seven or eight years and brands have shown a strong sense of courageous rebellion; they’ve wanted to be different and to express themselves in a different language. That attracted more and more attention from younger customers, who are willing to pay relatively high prices for these different products. While we wanted to be consistent in terms of SKP-S’s conditions and standards, we also wanted to create an environment in which street fashion could be sold alongside ‘classic’ luxury brands. The purpose of the visual universe we created in SKP-S was designed to create this mix of street fashion and luxury. We wanted to create an exceptional space where younger customers could socialize with each other, but we also wanted to create an environment in which creative leaders such as Jonathan [Anderson] could really express their talents. SKP-S has been open for just over a year and our customers have proven to be really interested in the store’s visual impact. More importantly, though, they are even more interested in the products on offer in this setting. For example, the limited-edition Air Jordan sneakers that we put on show each week have attracted lots of interest and attention from young customers. Also, the ski collection from Prada – that actually changed younger customers’ perceptions of Prada as a brand. For a designer like you, Jonathan, in the SKP-S environment, there’s an opportunity for you to push your product range and the way you present it in even more daring ways. Pascale [Lepoivre, Loewe CEO] should give you more budget for that!

Mr Ji, when you say you want brands to push their product range, do you mean stylistically becoming more daring, or are you referring to the frequency of drops, the overall amount of stock available, or the aesthetics of their presentations?

Mr Ji: All of this. In spite of the global pandemic, the Prada and Louis Vuitton stores in SKP-S are already in their fourth collection rotation in the past 12 months; Gucci is in its third. Really that is our principal goal for SKP-S: we want the brands and creative directors to use their spaces to make ever more daring attempts to break through all the traditional boundaries; to make even more creations, to show them in adventurous new ways, with a high frequency of change.

Jonathan, is it surprising to hear the chairman of one of the world’s leading department stores say, ‘I’m daring you to create collections and spaces and experiences that completely transcend the things we’ve previously known to generate success’?

Jonathan: It is incredibly rare. We are talking about taking conceptual risks with products, as much as with the space and environment in which they’re being sold – that’s what makes it so unusual. We have done several things at SKP and SKP-S that have been incredibly successful and which would probably have been less successful in a more traditional department-store setting. For example, for Loewe, we have a lot of artworks and objects in the space, which is different to our other stores in China. It’s a daunting process for a creative director, but so fulfilling because your vision isn’t being diluted.

‘I was keen to do this interview because I believe the creative dialogue with China is currently the most important aspect of the industry.’

Does that happen often?

Jonathan: Mr Ji knows this only too well, but in malls, there is this scenario whereby mega-brands are fighting over small square meterage. What is interesting at SKP is that no matter how big or small you are, if the product is not interesting or dynamic enough, it doesn’t get air time. That encourages brands to look outside their comfort zone. I agree with Mr Ji about the Prada concept in the store – it has really made the idea of Prada feel new again.

This clearly represents a new era of fashion retail based upon attentiongrabbing and spectacle-based fashion and its presentation to the world. For better or worse, is this going to define fashion more broadly in the next few years? Do you think that brands that don’t fit that spectacle-based way of presentation will inevitably suffer?

Jonathan: There are many things at play as we go forward; if we’d been discussing this a year ago I would have probably answered slightly differently. Globally, the pandemic is naturally going to speed up the decline of uninteresting things. And quiet or low-key could start to be considered almost irrelevant. Fashion had already hit a wall before the pandemic, in terms of the media, department stores, and how it was consumed globally. In the West, we have to battle to understand better that Chinese consumerism is growing at a far faster rate than in the West. While we may still have the brands, we are no longer the leaders in terms of retail consumption. I was keen to do this interview because I believe this need to understand the creative dialogue with China and the critiques we get from there is currently the most important aspect of the industry. Ultimately, the country’s shoppers represent our key consumers. Ten to fifteen years ago, it would probably have still been America, but we are moving into a period of shifting consumer geopolitics. The designer, CEO and shareholders are now listening to and having a creative dialogue with Chinese consumers. In earlier periods, we dictated what they wanted, whereas now Chinese consumers are telling us what they want. This is clearly going to initiate a fascinating moment for fashion in general. The power has shifted.

What are your own thoughts about Chinese culture?

Jonathan: I have a huge admiration for it. I collect ceramics and historically, Chinese ceramics, for example, are probably the most cutting-edge that ever existed, far ahead of anything in the West. They invented and the West just copied. I think we are heading into a period where the West now looks to Asia in terms of its consumers. And what is happening in Chinese consumerism will start to be implemented in Europe, and all across the West. Everything is shifting, and that’s exciting.

In what ways is this consumer-led dynamic influencing your work as a creative director, and is that even a healthy thing?

Jonathan: We have to be honest with ourselves: fashion is an art form, but one entirely driven by consumerism. As a designer, you have to listen, because this is the modern world; this is where we are. To be oblivious to the shift would be completely ignorant, and would make no creative or business sense. What I enjoy with Mr Ji is that it is a creative dialogue as much as a business dialogue. It is a give and take, not one-sided. When I was in China just before the pandemic, I loved travelling into the countryside and seeing people making things. It’s so different to London or Paris, you have to be there to understand it. You cannot preach to people in China and then not go and see the people and cultures of that market first-hand. This is my thing with fashion in general. You cannot say, ‘Oh, I’m going to sell to China, but I’m not going to engage with the culture.’ No matter if it’s people who make lanterns or make basketwork, you have to engage with the culture to understand, and this is where I think you have so much scope with creativity.

What do you see as the future of this relationship between Western brands and China?

Jonathan: I was recently watching the amazing Adam Curtis documentary called Can’t Get You Out of My Head. In it, you see the evolving relationship between the East and the West and how we have got to the current moment. After seeing SKP-S and studying the marketplace in China, I really felt that the consumer had changed, particularly compared to when I was there 10 years ago. The business leaders have changed; the dialogue has changed. There was always an appetite for the history of fashion, the storytelling, what that could be, but when I returned in December [2019], I was surprised at how much further things had evolved in terms of the arts scene, young collectors, department stores, designers. Going back to the Adam Curtis documentary, what is interesting in this moment is that all the landmarks that designers and department stores had are crashing down, so no matter what happens as we come out of this situation, we have to decide as consumers and as people what we want from things. What future do we want? What was happening before is not working any more – which is inspiring, because

how do we stimulate a new type of consumer? It involves more information, more tactility, and more spectacle. You just cannot ignore spectacle because the generation we are starting to sell to has grown up on that. Video games are more complex than ever before; they now feel like films in which you’re the lead protagonist; cinema itself has evolved significantly, as has art. So it’s no surprise that the way we shop has also evolved.

‘Western brands dictated what Chinese consumers wanted, whereas now those same consumers tell us what they want. The power has completely shifted.’

How do you think people are going to react in the short term?

Jonathan: I think we are going to experience a post-pandemic boom of people grabbing onto things, and of going out into the world and exploring. People really don’t want to be at home any more. The first thing that I personally want to experience is global travel; I want to go and see things I have never seen before. When I look back at being with Mr Ji in SKP-S, it was like seeing a snapshot of a new form of shopping. What I like about Mr Ji is that even though he is a very powerful figure in Chinese fashion, he has a genuine love of creativity. That is rare because it can so often be a dialogue only about numbers. Mr Ji is looking at the numbers

and realizing that creativity is what is driving diversity within fashion.

Why is that so rare?

Jonathan: Because a lot of businesses are ultimately driven by the bottom line while lacking creativity at the top. Everyone can and should be creative in business. It’s about having the right leaders who can see how to make money through creativity, rather than making money and then thinking about creativity.

Mr Ji, you’ve been listening to what Jonathan has been saying about this global shift towards the Chinese customer. What are your own thoughts?

Mr Ji: China has been experiencing extremely rapid changes over the past four decades. And because of this, Chinese consumers, enterprises, and also the government have a special love for innovation. Our consumers have traditionally been regarded as being conservative, but the reality is that they are highly determined not only to try new things, but also to try to initiate change themselves. This strong desire for change and for innovation has already been expressed over the past decade. Everything we have been doing in SKP has been driven by the needs or convictions of customers; we feel that we constantly have to change. The impact of the pandemic will mean that many Western brands will need to adopt a different mentality. Before Covid, some of them tended to have a certain kind of arrogance towards particular groups of customers. That kind of behaviour now has to stop, for the sake of those brands’ business. They shouldn’t just try and please certain groups of consumers – whether that’s Chinese, Japanese or American – but rather show adequate respect to all consumers and all markets. What I admire most about Jonathan, besides his creative talent, is his strong and genuine curiosity to learn about different cultures, his willingness to listen and get to know his customers.

What can you say about Chinese consumers that might surprise Western readers?

Mr Ji: They’re a lovely bunch of people, certainly SKP’s customers! If you’re willing to put a little dedication into creating something for them, they will reward you with their generosity – through their spending.

‘The pandemic is naturally going to speed up the decline of uninteresting things. And quiet or lowkey could start to be considered almost irrelevant.’

Jonathan, what have you understood about Chinese consumers’ behaviour, particularly the younger generations’, that simply isn’t understood by those outside the country?

Jonathan: Their amazing humbleness and humour; the same goes for Mr Ji. He brings a lightness and sense of fun to the idea of selling and getting to know the customer, as well as doing things outside your comfort zone. I did a pop-up for my own brand with SKP in November 2019 and it was really fun. I had never seen so many people; it was a completely different experience. By getting to meet the consumer in real life, not on a spreadsheet, you start to understand how to engage with them better. When I first met Mr Ji, he encouraged me to accompany him around the mall, to see it and go in the different stores. It was fascinating and rare to walk with someone who enjoys seeing people interact with products so much. I just don’t have that kind of relationship with other department stores; I don’t walk through Selfridges with [group managing director] Anne Pitcher; it’s a very detached relationship. Whereas I know that I could ring Mr Ji if I had an important question and he would help out. Similarly, when Pascale or Sidney [Toledano, CEO of LVMH Fashion Group] need something, Mr Ji is there.

How do you feel about Mr Ji’s comments about the arrogance of certain brands?

Jonathan: You cannot approach this with arrogance. Once you eliminate that, then anything can be successful. That is what I love about China: it doesn’t matter if you are the biggest or smallest brand, anything is possible. What I have learned over the past seven years working at Loewe, which is a bigger brand than my own, is that you cannot underestimate the gravitas and excitement of the Chinese consumer. The thirst for knowledge about fashion, about the making and the craft, especially in younger people, is phenomenal; they know way more sometimes than I do. In the West, we just don’t have that level of curiosity.

Why do you think that is?

Jonathan: I think that at some point in the West, the idea of luxury lost some of its appeal. Whereas when you look at the Chinese consumer, particularly the younger generation, they want to know where things are made, their intrinsic value, if they are historical or cutting edge; they want to understand the presentation. Above all, there is a willingness to question and to be ruthlessly critical, because the Chinese consumer wants brands that lead, not brands that follow. We used to be like that in the West, but seem to have moved on now. We might see a resurgence of it post-pandemic.

Jonathan, right at the beginning of your career, you worked in retail stores. What insight did that experience give you in terms of customer relations, merchandising and selling?

Jonathan: I first worked in the menswear department at Brown Thomas, a store in Dublin, and I also worked at Selfridges briefly. Then I met Manuela Pavesi, who was visual communications director for windows at Prada, and I began doing visual merchandising with her. The fundamental thing you learn when you are working in a store is that the design process is one thing, but the selling process is an entirely different one – and one that it is really difficult. When I was at Prada, we were creating windows and I learned about this idea that to be able to anchor the clothing six months after a show, you always needed to orchestrate a creative drama, like a stage set. By going through the process of working on a shop floor or doing visuals, I always keep in mind when I am designing that the process takes an entire year, from the beginning to the launch. It’s like a circle with overlapping circles of pre-collections and then Christmas. When I am designing or in particular editing a collection, I like to think of how to merchandise the collection, like building a rack of clothes and constructing how it could actually exist in a wardrobe. My shop-floor experience has had a massive impact on me in terms of how I build up a collection.

In terms of merchandising a collection and building racks, are the ancillary worlds that brands create for their products increasingly important? Is it changing the way the clothes themselves are being designed?

Jonathan: Absolutely. The space has become paramount. Ultimately, if there is no sense of context, of setting, of environment, then the clothing very quickly becomes nothing. You have to ask yourself, what are we trying to sell, what are we trying to say? And the answers have to come from a creative space. Of course, online shopping is increasing, but when you are looking to sell a brand message, you need to know exactly what the door handle or the hanger is going to look like, or how the salesperson will put themselves across. These things add to the creative energy. It’s also about tactility. Humans have understood the concept of stores since time immemorial. People have always wanted to sell and trade things through a tactile approach. It’s just as much about selling a service. The personal engagement with someone, with being able to touch things, will never go away. It may decrease in terms of volume, but then the players left in the physical shopping market will ultimately become more powerful.

Mr Ji, what is it about Jonathan’s work – both his designs and his overall creative direction – that connects with your customers?