Interviews by Rahim Attarzadeh,

Claudia Donaldson

and Jonathan Wingfield

As the world continues to face the Covid-19 crisis, System has nevertheless been keen to look forward. So we decided to explore the effects – positive or otherwise – that the pandemic’s enforced isolation and immobility might be having on the cultural spaces that fashion and its peripheral domains occupy, and what the future holds for them.

We embraced the ambiguity of the term ‘spaces’, its fluidity allowing multiple visions and interpretations, all different, all valid: the concrete plans of a public cultural institution; the shifting geopolitics of the global market; the visceral desire for congregation; and the environments we create in which we communicate and express ourselves. System invited a group of unique voices from the worlds of art and culture to share their own thoughts and feelings about the future of spaces: architect Rem Koolhaas, filmmaker Jenn Nkiru, creative collective No Vacancy Inn, and museum director Chris Dercon.

The conversations on the following pages convey a collective sense of reflection, uncertainty and turbulence, yet retain a feeling of cautious optimism. As Chris Dercon sagely puts it, ‘I don’t want to say that it’s an exciting time, but it is an important time.’

Rem Koolhaas

If the future’s your subject du jour, an ideal starting point is a chat with Dutch architect, urbanist, theorist, and all-round big thinker Rem Koolhaas. With his architecture firm OMA, he conjures up the kind of buildings that are as spectacular as they are pioneering, mixing intensive research and investigation with a taste for avant-garde design. In Asia, he’s delivered projects such as CCTV, the monumental headquarters of China’s state broadcasting company in Beijing, while in the US, his work includes the intricate and multilayered Seattle Central Library. There’s also his 20-year collaboration with Prada, working continuously on the brand’s shops, set design and its art foundation in Milan. Perhaps more than any single project, though, Rem is best known for being a kind of one-man think tank, travelling the world and bringing his experiences and encounters into new buildings, books, exhibitions, and above all, ideas. Due to Covid-19 restrictions, Rem was uncharacteristically at home in Amsterdam when System Zoomed in to discuss the importance of naivety, overdosing on the smoothness of digital screens, and the physical serenity that comes with living without jet lag.

Jonathan Wingfield: A spectacularly obvious opening question: what made you want to become an architect?

Rem Koolhaas: At some point in, I think, 1966, I went with an architect friend to Russia, which at the time was pretty inaccessible. My friend was doing research on constructivism and Soviet art of the 1920s and 1930s, and we met a number of survivors from that period. I also saw first-hand that in the 1920s, Russian architects were less concerned with shape and form than they were with proposing alternative ways to live. One project in particular left a big impression on me: a proposal to abandon cities and replace them with linear chains of single rooms on stilts. Each room had a small external staircase, which would lead into countryside or forests, and in each room would live a single person. This was not only a question of dismantling the city; it was also dismantling the family. If people wanted to stay together, they would simply form a chain of these single rooms, and every half a kilometre there would be a communal school, communal hospital, communal kitchen. It was such a graphic demonstration of how architecture could express imagination about how people could live and in what kind of conditions, and what the possibilities of life in the future could be. And it led me to think about pursuing architecture myself.

Do you remain as awestruck about the possibilities of architecture, as this almost naive ideal for living?

I used to be very sceptical about architecture, thinking that it was a regressive discipline with little affinity for the modern world, which constantly missed the point of technical developments. I’ve recently become much more interested in it though, as a profession that depends, on one hand, on almost scientific precision, and on the other, on what you refer to as naivety and I would probably call idealism. Without that naivety, architecture becomes very banal and flat; it’s something that you really have to protect and incorporate.

We’re speaking in February 2021. You’re well known for your peripatetic existence; how has the forced immobility of the pandemic affected you and your work?

Most of the projects we were involved in are still going ahead, but I’ve also been quite adamant that working remotely or via Zoom is not enough to force creative insights or breakthroughs, and so, at regular intervals, when it’s been necessary, we have created moments of togetherness – of course, with new distances and in new environments and sometimes in the open air. But at the same time, it’s been extremely interesting to begin to have a totally different relationship with my home, with the city of Amsterdam, with the Netherlands. Many people have had that experience of taking their own environment a lot more seriously, which has its good sides and its claustrophobic sides. The other great thing about enforced immobility is that there is no jet lag, which creates a kind of physical serenity.

For many people the pandemic has brought about accelerated or intensified feelings of nostalgia. What are you feeling nostalgic for?

For the past five years, I’ve been feeling very nostalgic about something that I tried to articulate in the Venice Biennale, where I said that the current culture has replaced the French Revolution’s motto of liberté, égalité, fraternité with ‘comfort, security and sustainability’. This has created a complete aversion to risk. I’m deeply nostalgic for a period in which risk-taking was more respected, and even considered a crucial component of civilization and coexistence. That aversion to risk has clearly multiplied in the pandemic. Right now, risk almost seems like an obscenity.

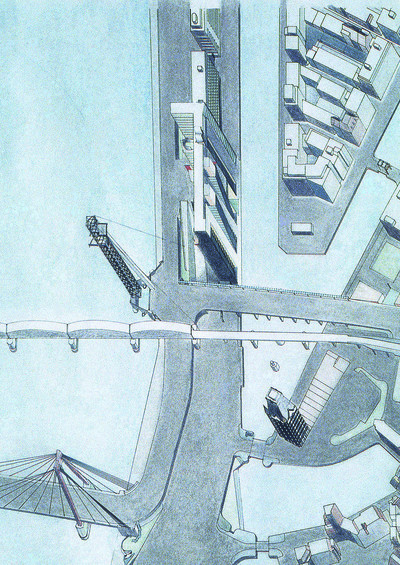

You recently collaborated with American Express on a ‘Centurion Art Card’ that features an image of one of your unrealized projects. Can you tell me about the original project, and its renewed significance in the context of a credit card?

One of the effects of the pandemic has been a total proliferation of the credit card. It’s become totally ubiquitous, even more so than when American Express first said they wanted to work on one with us. The project we did is called Boompjes, which literally translates as ‘small trees’. It was one of those real-life movie moments: I was invited to see a councillor for Rotterdam who was sitting in front of the map of the whole city. He asked me in a kind of grandiose tone, ‘Where do you want to build?’ There was a very interesting site on the river, defined on one side by a bridge, on the other by the water, on the third by the highway, and on the fourth by a building. It was constrained, but on every side there was a different condition. The project we developed there represented the transition between being a theoretical architect and a real architect, with a real building, in a real city. All of the elements in it – the programme, the location, the experience – were derived from one single drawing, because we needed something condensed to convince the politicians. That drawing, the drawing now on the credit card, represents a transitional moment for me.

‘I’m deeply nostalgic for a period in which risk-taking was more respected, and even considered a crucial component of civilization and coexistence.’

The project ultimately never got built, which is such a common thing in the field of architecture. How did you feel at the time?

We work hard to make all of our projects happen in the real world, but if they don’t, we at least demand of them that they make a statement relevant to the discipline of architecture and explore an issue beyond the individual project itself. It felt deeply crushing when that project was not made, but it was also an incentive to find ways to establish a career in architecture through other forms, such as through books and writing.

This time last year – almost to the day – you were at the Guggenheim in New York, opening your exhibition Countryside, The Future. The theme now feels eerily prescient, given the ways that we’ve seen cities become these empty and somewhat dystopian vessels, and how the countryside has become so profoundly appealing to many city dwellers. What was your original thinking behind the exhibition, and how has the pandemic altered or intensified its meaning?

There were two original triggers. Over the years, I have often taken holidays in the same village in Switzerland, where there was a lot of farming, and which, as a village, felt stable. But at some point, maybe 15 years ago, there was a radical and rapid transformation. The original population of the village disappeared, farms disappeared, cows disappeared, and were replaced by boutiques. You saw this great acceleration of change, much faster than I had ever witnessed in a city. That was one thing. The other is something the UN reported in about 2007: half of mankind was living in cities, and in 30 years that percentage was going to increase to 70 percent. It took a while to realize how incredibly radical that would be. The larger part of the world would undergo a halving of its population, which would be a total revolution…

…a countryside revolution that you wanted to investigate?

The city has become the inevitable subject in architecture, partly because it was supposed to be the future of mankind. So, almost out of contrariness, I then said, ‘OK, if the city is so important, what about the countryside?’ We looked for about 15 rural sites in the world, where in each case something unique was happening, something that could tell us about the changes to the countryside.

And then the pandemic happened.

In the beginning, people had thought it was highly eccentric of us to focus on the countryside, and then suddenly the countryside became the only kind of foreign place they could go to. That is, of course, also the first step in gentrification. The countryside itself does benefit to some extent – it feels slightly more credible – but it’s definitely not about getting a second house in the countryside.

Was a pandemic something you’d ever had to formally consider when working on a building or an urbanism project in the past?

When I was working on the CCTV building in Beijing we were interrupted by the original wave of SARS; in China, that had an incredibly devastating effect, maybe even more radical than Covid-19. So, yes, I experienced that whole scenario and its paralysing effect on the society. Being completely locked down in Chinese cities in the winter was an amazing thing to see, and so was the ambition to overcome it.

What would you like to see change in architecture in the forthcoming decade?

As an architect, I’m so stuck in the current moment that predicting the future makes me nervous. For instance, I have absolutely no idea whether that shift to the city is inevitable, or whether a shift back to the country could be imminent. What I do have is a very strong expectation that the future will be much less unilateral than previously thought. In about 1991, it seemed that history was over and that the world would become a single, large, integrated economy and a single, large, liberal political system. But it is obvious now that that is not going to happen and that confident predictions for the entire world are untenable.

‘Overdosing on the smoothness of a screen – particularly the fake smoothness of the rendering – makes authentic feeling in architecture vital.’

Do you think architecture’s greatest current and future concern should be its impact on the environment?

Looking to the future, you won’t need a hierarchy between beauty, practicality and sustainability. This will require a complete rethinking of architecture and also a complete reimagining of the science and knowledge necessary to produce architecture. To truly think about sustainability, constructing in wood, recycling or slogans is not enough. The environment will be not so much a priority as an enabler of an entirely new architecture.

Do you feel a sense of responsibility in initiating that shift?

We certainly haven’t initiated it, but we have thought about it. One thing to be said in favour of architecture is that in the 1960s, everything we know now was already known in terms of the limits to growth, the effects of global warming, the need to change the economy. So any architect who trained in my generation is still vaguely committed to all of that. But it’s only now that there is the general political awareness and, increasingly, the obligation to change.

The pandemic has highlighted, for better or worse, that we can fulfil many of our needs online. How do you think this might affect the role that physical spaces play in our lives?

I honestly have no idea. I have a number of friends and colleagues who engineer their Zoom backgrounds to create a kind of virtual space – a paradise or a serious, intellectual environment – from which to present themselves. Maybe there will be an increase in the use of virtual reality as an effective architectural or virtual environment, as a form of identity-building architecture, which may be good because then architecture can focus on other things.

The Prada shows that you worked on earlier this year presented models walking through small spaces in which the surfaces had a kind of exaggerated tactility: voluminous fake fur, resin, marble. You could almost feel them, even watching through a mobile phone. Might this exaggerated tactility become required in our physical spaces, since the digital documentation of our lives will dictate how we experience much of the world?

I agree that the screen affects things in terms of texture and surface. If you look at our own recent work, that might be why we used a very tangible and rough form of travertine in the Qatar National Library. So, yes, I’m sure that overdosing on the smoothness of a screen – and particularly the kind of fake smoothness of the rendering – makes some kind of authentic feeling in real architecture very important.

Everyone talks about missing public cultural spaces, but in reality do you think there might be a longer-term reluctance to re-embrace them?

As soon as it becomes possible again, there will be a real eagerness for interaction, on the level of friendships, relationships, tribes, milieux, to reassume traditional roles in traditional environments. For example, a serious eagerness to go back to the theatre.

Would you say that aesthetic beauty is still a defining ambition in architecture, when it feels more broadly that practical or ethical concerns are more significant to our collective future?

I’ve always found it complex to pursue beauty on its own, and have always been incredibly excited when beauty emerged almost inadvertently or unintentionally. For me, beauty is so elusive that if you go after it, it will escape. But if your efforts are about intelligence or articulating particular moments with a particular sharpness, a beauty can emerge. Beauty remains very important, but more as a kind of intellectual moment than as a simply sensual moment that you can work from. We’ve long been working on preservation strategies, and exhibited some of the work at the 2010 Venice Biennale. People typically want to preserve the most beautiful, unique, exceptional things, but I am equally interested in preserving the generic. If you want to understand the past, you need to know what it looked like, rather than creating a misleading perception that comes from only preserving the beautiful things. I guess what I’m trying to say is: don’t just look at the highlights.

Is there a building somewhere in the world whose wildly appealing beauty you’re quite happy just to surrender to?

Many. Almost anything Roman, almost anything in Paris, almost anything in Beijing, almost anything on Red Square – I’m very tolerant.

Jenn Nkiru

This is Jenn Nkiru’s time. The London-born filmmaker won Best Music Video at the 2021 Grammy Awards for ‘Brown Skin Girl’, her latest collaboration with cultural powerhouse Beyoncé Knowles-Carter and featuring a cast including Kelly Rowland, Lupita Nyong’o, Adut Akech, Aweng Ade-Chuol, and Naomi Campbell. Nkiru’s meteoric rise began in 2014, fuelled by films that are rich multi-sensory experiences, combining archival material, assemblage and live footage in an exploration and re-definition of Blackness. These have included award-winning 2017 short Black Star: Rebirth is Necessary and 2019 documentary BLACK TO TECHNO, which unearthed techno’s roots in Detroit. In an ongoing attempt to reconcile the past with the future, Nkiru uses aspects of the built environment to create dynamic dreamscapes, occupied by people exploring a metaphorical space of transcendence, negotiating the boundaries between their interior and exterior lives. With confidence, empathy, and technique, Nkiru creates space for humanity to find itself in her work, while exploring her own cosmic beliefs drawn from Afrofuturism and late jazz pioneer Sun Ra. Having recently returned to London after an extended period of travelling and shooting, Nkiru caught up with Claudia Donaldson, publisher of Cloakroom magazine, to discuss the importance of mystique and why she loves Peckham like Spike Lee loves Brooklyn.

Claudia Donaldson: So you’ve been away for the past five months, right?

Jenn Nkiru: Yes, I started off in LA, and then I went to Hawaii, then Madrid, then Mexico City. And once I wrapped in Mexico City, I went to Oaxaca for a break. I planned to be there for seven days and ended up staying four weeks. I just needed some reprieve. [Laughs] And the day before I left we’d won the Grammy for Best Music Video for ‘Brown Skin Girl’. So, along with needing physical rest, I also took a moment of reflection, trying to take stock of where I’m at, where I want to be, where I want to go next. I am constantly trying to reflect and reframe. It’s interesting that this conversation is all around space, because 2020 was the first time in

a long time where I had to be physically stationary in one space.

You grew up in Peckham in South London and once said, ‘I love Peckham like Spike Lee loves Brooklyn’, which makes me smile. You lived your formative years there, and then you left London in your 20s to go to Howard University in Washington, DC. What did you miss most when you left?

It’s where I grew up, where I went to school. It always felt like the perfect microcosm for what a blending of cultures could look like. I didn’t start travelling until I was 13, with my parents.

Your dad used to hold salons at home, right? Inviting people from all over the world to come and talk. His work was journalistic and political, and your mum worked in computer programming. How would you say that they influenced you?

Our home was really interesting. We lived on a North Peckham estate, a space that is lower-working class, and yet my parents had these qualifications. My dad for the majority of my childhood was a student. My mum was a student for some of my childhood because I remember going to uni with her.

Were you proud of her?

Absolutely. As a kid, your environment is your environment; you don’t know any different. We just had our routine! [Laughs] We’d hop on the number 12 bus, stop at Wimpy, this guy would drop a Wimpy burger in my sandwich box, and we’d head off to the university where I’d sit in the library. My mum would be there with her school friends, working and programming. My parents were as much individuals as they were a couple. And they were very much the inverse of what people typically think parenting should be; they were like, ‘You’re going to have to figure yourself into our lives.’ Not in a cruel way, just, ‘These are my interests and this is what I do and you’re my kid, so you can figure yourself out.’ That level of independence. And as much as they were very much Nigerians – very traditional in some respects – they were also very liberal in ways that maybe some of my peers’ parents weren’t.

So you felt like you were encouraged to have a voice?

Definitely. What I am talking about is this blend of culture and curiosity and having parents who are thinkers. We were encouraged to be curious and ask questions and, you know, if you feel something is wrong, how would you make it right? You don’t just complain about things; you have to engage. It’s all about engagement, and having a vision of what you feel things could be. And there was a very strong conversation being held around Pan-Africanist ideas and politics and diplomacy and democracy. Very lofty things falling on the ears of a child, but I was still invited to give opinions. One thing I really love, culturally, is parents giving the sense of a space that they have created for themselves, of the life that they have created for themselves, and then their children have to find themselves in that space. That also meant that they invited us in; we were watching, observing and getting involved in a real, dynamic way. These kinds of experiences allowed me to understand different backgrounds and different perspectives, based on being, for want of a better term, privy to these things. And there are the transformative powers of the spaces I grew up in, because Peckham now is not what Peckham used to be. We weren’t middle class; we weren’t living in a neighbourhood with detached houses.

‘I consider myself tenacious. I’m not here because people said, ‘Yeah, she should be in the room!’ I’m here because I kept knocking on the door.’

You talk about it in a tender way, which makes me think of Andrea Arnold; I read somewhere that you said her film Fish Tank is one of your favourites. And it just made me think about women in cinema and the parallels. You both share unconventional professional backgrounds. Andrea Arnold was a dancer on Top of the Pops and a TV presenter before she became a filmmaker, and you studied law and worked as a commissioning assistant at Channel 4. Would you say that these roles in your life feed into the work that you’re making now?

Absolutely. These different aspects aid me in different ways. I consider myself a tenacious person. I am not here because people said, ‘Yeah, she should be in the room!’ I’m here because I kept knocking on the door, you know? I feel like I’ve made choices in terms of how I tend to view things; I’m always looking for the soul in the thing.

There’s this beautiful tension between the local and universal in your work. Individual versus collective. Soul and transcendence. There’s this constant play in which protagonists are often closing their eyes, a feeling of constant negotiation between the boundaries of your interior life and your exterior life.

I’m always looking for universality and specificity. If we can be specific, it actually does resonate universally in a really exact way. And then there’s my own cosmic belief of us existing in multiple realms and the kind of jostling between the external, performative, representational side of who we are, versus the internal, somatic kind of feeling and being of who we are, and what that conversation is, and how we see spillages and leakages of these things, which tend not to happen in the more well-choreographed moments in life. In the creation of work, there is always a sense of these moments, so that you can key into the emotionality of this person’s experience in this space.

There’s such a strong sense of emotional space in your work. In your video for Kamasi Washington’s ‘Hub-Tones’, the use of styling is emphatic in drawing this out. You’ve got this incredible woman with bejewelled eyes wearing a silver headdress. She’s like this Nina Simone figure with incredible obsidian nails, clutching a tambourine. She’s totally in her emotion; there’s a transcendence. She looks totally free. You seem able to self-connect and intervene, to press pause, if it’s needed. So on a day-to-day basis, how do you keep spiritually fit? Is there a practice?

Such a good question. I don’t know if I have a practice. I try to find spirit in all I do, if that makes sense: in my consideration for others, in how I’m feeding myself, in what I’m tolerating, in where I’m finding my joy, how I’m talking someone through an idea. Finding moments of stillness and aloneness even just for one minute. On a more day-today level, in spaces that are often moving so fast, I’m trying to keep mindful and present and respectful and in close conversation with my humanity. Because I feel like there are so many things – situations, people – that can pull you out of that. I’m always trying to stay true to self on some level.

Especially on large-scale productions when you’re leading a big group of people, bringing emotional intelligence to what you’re doing is so integral to the success of a project. Going back to the styling though, it’s an important part of your film-making. You worked with stylist Ib Kamara on Rebirth Is Necessary. What was it like? Had you worked with him before that?

I had seen Ib’s work really early on and I just thought he was brilliant. I remember mentioning to him that I really wanted him to do costumes for Rebirth is Necessary, because I felt like we were kindreds on many levels. I try to work with people who question ideas of how things should be on a very unapologetic, self-determined, curious level. My work serves as reportage and evidence of the process. That’s all the work is – it’s just a materialization of an experience that we all shared at some point in time. When working with collaborators I always think about being at peace with my ego and letting people come into any space that I create, so they feel confident. Even in commercial projects, I say, ‘You know that idea you always wanted to play with and do? I’m giving you the space here to do that.’ That’s how we get work that is pushing things and pushing perspectives. Ibrahim is, you know, just an incredible… I miss him so much! [Laughs] And we actually did a piece with Neneh Cherry together, as well.

That video for ‘Kong’ is beautiful and Neneh looks incredible in it. There’s this tension of the unseen and seen. The hat covering her eyes…

I love that. On a collective level, there’s no longer much sense of mystique and curiosity and experimenting with the unknown. Everyone wants everything laid out. That’s not interesting to me. There’s a really childish magical-ness that I’m obsessed with and have held on to since I was a kid. And a lot of the time I’m focused on women, too, looking at the feminine interior. I didn’t want to do ‘Buffalo Stance 3.0’; Neneh’s a woman over 50. How do we give her humanity, show the fullness of her womanhood, and allow the audience to get a sense of who she is and where she’s been, her confidence, but also her curiosity? There’s a lot of speculation involved. It’s not like I’m reading textbooks and coming to an exact estimation. I’m giving my dreams, my relationships with spirit, with academia, with pop culture, with my friends, my family, my contemporaries… I’m giving all of these things equal regard.

‘I’m not reading textbooks and coming to an exact estimation. I’m giving my dreams, my relationships with spirit, academia, pop culture, friends, family.’

You’re also combining rigorous historical research with poetic imagery. How do you strike the balance between intellect and emotion?

I don’t know if I’m reaching the balance; I’m feeling my way through very intuitively. I haven’t boiled it down to a science, but what I am really conscious of is joy. I like joy, and I like pleasure. [Laughs] So how do we take these ideas that could feel stuffy and intellectual and make them pleasurable?

You make them ecstatic. In my notes, I wrote ‘remember ecstasy’ because it’s such an ever-present feeling in your work; I am reminded of dancing and coming up on ecstasy. In BLACK TO TECHNO, there’s a multilayering of storytelling at play – narrative, visual, sonic – which reaches a climax as the narrator explains a near accident working in a factory in Detroit. He has this metal-stamping machine, which he calls Ginny, and the only time he ever put his hand into the machine, the press didn’t come down, and then bang, the music comes in. Watching it, I felt how I used to feel when I would go clubbing. When I stopped taking drugs, I thought I was not going to feel the music any more, but actually, it never goes away.

It’s in the music! I had a really beautiful conversation with the academic Tina Campt back in November, and I was highlighting the differences between freedom and boundlessness. And my definition, as I explained it to Tina, is that freedom is concerned with the reclamation of something that’s been taken away, whereas boundlessness is this more innate, human birthright that we’re all familiar with and is supremely cosmic. And it’s why you have such a world-tuned engagement when you feel it. The music doesn’t feel unfamiliar – the feeling is so sweet that you don’t have to tell your body what to do.

I love that. Music and its origins are so inherent to your film-making; your work helps restore Black culture to its rightful place. In BLACK TO TECHNO, we are shown Detroit as the birthplace of techno and Sister Rosetta Tharpe as the creator of rock and roll. Has she always been an influence?

I’m actually doing a project in response to a building Rem Koolhaas is making, and I’m looking at her in that context. His firm OMA is designing the new space for the Manchester International Festival. It’s the old Granada studios in Manchester, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe made her way there at one point and played. So, it’s interesting that we’re having this conversation; the project is literally around the rapport between space and architecture and people.

Well, that’s serendipity. He’s one of the interviewees for this series.

Oh, wow! If it wasn’t for the pandemic, we might have been having this conversation in that context, because that project will be a piece around my reading of architecture and space. It’s still to be shot; it might be released next year.

I loved how BLACK TO TECHNO explores the built environment, how that shapes and influences musical expression and vice versa. Can you tell me a bit more about the physical aspects of creating spaces and backdrops in your films, the actual process?

My focus is always on feeling, so I’m like, ‘I need these ingredients; this is the feeling I want to elicit and these are the ingredients that I want to add.’ I’m always creating space with as many charged elements as possible to see what happens when they come together. There is just a scratch of the exactness of what things could be, but it’s never defined. I’m looking at spaces like a lump of clay, at the sculptural aspect of what it is that I want to make exist, and I just have to uncover it. I feel like that’s where things fall short, when people become so beholden to an idea and in anticipation of what it must look like. That’s when everything stops growing, you know? I’m more like, ‘What is the feeling here?’ And I just keep tuning, tuning, tuning to the frequencies until it feels like the feeling. I enjoy my process; I don’t always know exactly what everything is going to look like. For some people that might be scary, but for me, it’s exciting.

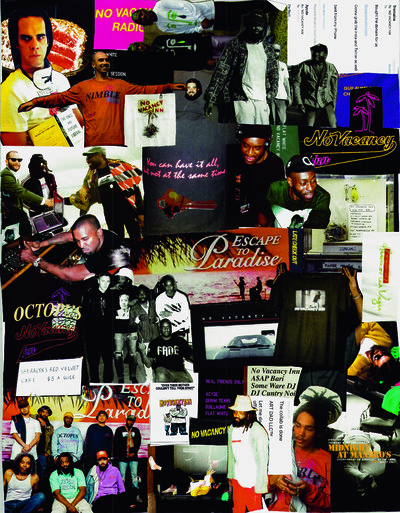

No Vacancy Inn

Founded in 2015 between New York, Miami and London by Ade ‘Acyde’ Odunlami, Tremaine Emory and Brock Korsan, No Vacancy Inn is a multi-disciplinary creative collective moving between and combining music, fashion, radio and nightlife. As hard to define as it is to pin down to any particular place, No Vacancy Inn appears and disappears everywhere from Basel to Bali, organizing pop-up stores in hotel rooms, working on sneaker collabs with New Balance, and clothing collections with Stüssy, as its founders forge a fast-growing reputation as cultural catalysts and visionary agent provocateurs. They remain best-known, though, for the parties they’ve staged in different spaces in major cities around the world, from basements to rooftops to suburban kitchens. These now-legendary events – playing host to musicians including Kanye West, Frank Ocean and A$AP Rocky, and creatives such as Tom Sachs, Virgil Abloh and Matthew Williams – are spoken of and relayed as IRL cultural touchstones that echo around and are amplified by the digital world. The trio spoke to System about the true meaning of social media, the post-pandemic future of congregation, and how to make the intangible the key.

Rahim Attarzadeh: Before we talk about the future of spaces, tell me about how No Vacancy Inn came into being?

Ade ‘Acyde’ Odunlami: My original instinct was to create a physical space, a store. It was also that period in London when there weren’t a lot of concept stores. When I was growing up in London, all of my culture came from record stores and clothing stores. Some were places where you could get a T-shirt and there would be a load of flyers for club nights and records, or associated ephemera. This was all through the 1990s and the 2000s and then it changed because renting spaces in London became more expensive. I wanted to replicate that nostalgia. One of the original ideas we had, because we spent so much time travelling, was to inhabit hotel rooms and turn them into stores. If we were hanging out in the Hôtel Costes, we’d get the biggest room we could and turn it into a popup store. We’d do the same at the Sixty LES or the Roosevelt. No Vacancy Inn is a pun, playing with the idea of hotels and rooms.

Tremaine Emory: No Vacancy Inn, never checked in, always checked out!

At No Vacancy Inn parties and events, the human presence becomes like a transformational moment. Could you look back at an event that really typified how you consciously prepare a space and a set of conditions that – once people were added – became an incredible moment of congregation?

Tremaine: For the launch of our New Balance 990 collaboration, we transformed this space next to the Union store on La Brea into an ephemeral hotel room. We tasked ourselves with making something that didn’t feel transactional. We had a mask on the wall from Papua New Guinea. We went to Amoeba Records and bought a bunch of VHS films we like – like Bull Durham – films that make us feel something. We had books from one of our favourite bookstores, Arcana Books. We had our friend Jenny Tsiakals, from Please and Thank You vintage store in LA, who is probably the best connoisseur of vintage, pull stuff that she would pull for myself, Acyde and Brock. We had a DJ set up at the foot of the bed, vinyl, CDJs, couches, flowers. We just really wanted to make a space where people didn’t feel like they were being shuttled in and out.

In a post-pandemic world, do you think youth congregation will rely on physical space as it once did?

Acyde: What’s going to be interesting is the paranoia of going back to spaces, maybe in 2023, and being enclosed in a space where you could get sick. We’re going to have to overcome that paranoia. Obviously testing and Covid passports; it’s an interesting challenge. Ultimately the kids want to congregate and be together, sharing the same kind of energy that you can feel coming off the pages of Ian Schrager’s Studio 54 book.

Tremaine: Pandemic at the disco!

When considering the physicality of the spaces, do you subconsciously choose venues that are steeped in rich cultural history? I remember going to some of your parties at the Scotch of St James in London and I was wondering if you picked that club because of its Swinging Sixties history, with Jimi Hendrix and the Beatles and so on?

Acyde: Interesting question. The most important thing for me and I think for us as a team, is the functionality of a space to inhabit an idea in the best possible way. If it’s a club it has to sound good; I have no business being in a club that sounds terrible. The thing about the Scotch is, we discovered it was a live venue and all these different people played there, and these people knew about sound. So if they played there and they haven’t changed the space, then it is probably good. The space needs to adhere to the right mathematical equation for sound to travel. That’s really what we are enchanted by. The purpose of the physical space is to house music.

Tremaine: The first time we DJed in the big room – this is before you heard Top-40 hip hop in nightclubs – we had to fight to play rap music. I’m not talking about the 1980s or 1990s, but the last decade. One of the owners comes to me and said Dita Von Teese is about to leave if she hears one more rap record, so Acyde put on Tyler, the Creator. We didn’t choose the physical spaces. We got in where we could fit in.

Can you recall a venue you hosted, where the physical space itself was in synergy with challenging the system or a changing of the guard?

Brock Korsan: We were in Paris and Will Welch from GQ hit us up to say we’re going to do something tonight at L’Avenue. The next thing you know, Acyde is playing the most irreverent songs. It was one of those moments. Within such a tight space, it seemed as if time stood still.

Tremaine: That party was around Virgil’s first Louis Vuitton show; it represented the changing of the guard.

Acyde: I just remember Virgil saying you can play anything you want if the crowd trusts you. All I do, when playing records, is share cultural milestones that I find interesting. Moments of culture caught as sound; one record represents 1977, one 1987, another 2017. The physical space was the crystallisation of this ideology.

‘I am sick of disparaging social media. I think it’s easy to use it as a proverbial whip to beat young kids with because that’s all they have.’

Do you think culture needs a geographical capital now?

Tremaine: The reason why that worked in the past is because you could afford to live in cities. I feel we do a disservice to these kids saying you have to come to Paris or New York or LA because it’s too expensive – it destroys them. The culture you foster from the place you grew up in is just as important. I knowthat’s tough, because with some of the places where these kids come from, it isn’t safe to be themselves.

Brock: Currently within the US, there is huge migration to Austin and Nashville. If we are doing things virtually, we don’t have to absorb these high costs of inflation to be somewhere that you deem culturally relevant. I think we are going to find new ‘capitals’ of culture. That is happening right before our very eyes.

Acyde: People went to cities to get away – look at New York in the 1970s. Within that space, New York gave birth to several genres of music. Punk, rap, then hip hop, disco, salsa. That happened because the city was more or less bankrupt and that’s why free jazz appeared. Now in this era of Covid, there are parts of London that are getting abandoned because rent is astronomical, so all of a sudden, cities are becoming open spaces again. A futurist thinks about how to build a new city that has the natural alchemy that comes from these cultural collisions, and which sustains culture. That’s why Kanye West is so interesting. He showed me the plans for what he is trying to build in Wyoming. He’s gone full Buckminster Fuller, with sustainable pods and underground living. He said when he was a kid, he didn’t know anyone who lived in great architecture, and neither did I until I met our friend Caius Pawson. He was the first person whose living surroundings were actual great architecture. We all grew up in these brutalist tower blocks in London, leftovers from Le Corbusier’s communal living idea.

Will No Vacancy Inn own a physical space in the future?

Acyde: When you think about Supreme or Stüssy, a part of their ability to connect is that they actually have physical spaces where people can live within the brand. We need to dialogue with the kids who buy our stuff and interact with us. I think that is the point about space, to bring it 360° to your overarching theme. No Vacancy Inn could be a hotel or a store, or a wall for social climbing if that’s what people want.

Will physical interaction remain at the core of spaces and No Vacancy Inn, despite living in an Internet age?

Acyde: If you look back at the conception of skateboarding, it had to happen outside. No one skateboarded in their own living room successfully. Kids in California found abandoned swimming pools and turned them into skate bowls. They took what spaces already existed and made them work for them. We now have this virtual space that never existed back then and within that we are having these conversations through our own parcel of space. How people absorb information through a physical, virtual or personal space is the entry level of stimulus we need to progress.

Brock: I think the Internet and technology has created a great migration for artists and creatives not to have to be in these physical spaces and for their work to live on virtually. On one hand, the Internet has become this ceaseless digital space or diaspora for documenting sub-cultural activity, but on the other hand social media has made culture appear more ephemeral today.

Acyde: Social media is just a tool for access; it’s a skeleton key to the world library of information. I am sick of disparaging social media because I think it’s easy to use it as a proverbial whip to beat young kids with because that’s all they have. It’s only a point of entry.

Tremaine: We’re cultural anthropologists. Andy Warhol has been dead since 1987, but he is still art-directing culture; just like Miles Davis who died in 1991. That is the highest form of creative direction, existing in the real world. It’s a derivative of real culture. Social media is just the CliffsNotes of culture. Jay-Z has this lyric where he is like, ‘When you could look in the mirror like, “There I am”.’ When you are looking in the mirror, no matter what type of space culture is manifested in, you are the cultural provocateur.

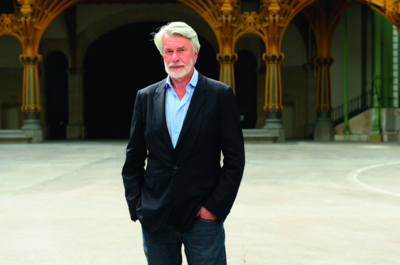

Chris Dercon

As president of the Réunion des musées nationaux-Grand Palais, Chris Dercon is charged with the future of 34 of France’s national museums, visited by 2.5 million people in a normal year, and including many of the most prestigious spaces and institutions in Paris. In his long career, Dercon has made a name for himself both as an innovative producer of popular exhibitions – including one of the first museum shows of Martin Margiela’s work and the hit Tate Modern exhibition Matisse: The Cut-Outs, which transferred to MoMA – and as the curator of some of the world’s most dynamic cultural spaces, from PS1 in New York, to Munich’s Haus der Kunst and London’s Tate Modern, where he oversaw the Herzog and de Meuron-designed extension. In Paris, his latest construction project is the Grand Palais Éphémère, a huge temporary structure designed by architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, set to replace the majestic iron and glass Grand Palais during its renovation. Chris Dercon met with Claudia Donaldson on Zoom to discuss rituals, public places, intimacy, and why it’s time to take museum shops more seriously.

Claudia Donaldson: Chris, it’s great to meet you. Where are you Zooming in from?

Chris Dercon: Paris, from my office opposite the Bassin de l’Arsenal. We have a few offices… I mean, we do have a lot of sites right now! We have two building sites: the Grand Palais Éphémère, on the Champ-de-Mars, and on the other side [of the Seine] the Grand Palais, which we are going to close in a few weeks for a complete renovation. Altogether, it’s a 75,000 square metre area: an interconnection of three different buildings in the heart of Paris, bordered by the Champs-Élysées, the Seine, and Les Invalides.

The renovation of the Grand Palais started in 2018, right?

It actually started in 2013. There was a competition in 2013 and some plans were made, but things have changed in the meantime. The questions we were asking about cultural infrastructure in 2013 were completely different to those we are asking now, and not just because of the pandemic. We have to simplify things, make them safer. We have to think about the economy, about sustainability. And we have to think about museums as cultural infrastructure that is always going to change, I think, for the better.

What do you think the Grand Palais represents to fashion as a medium of spectacle and congregation? Hermès hold its Saut horse trials there – they even named a bag after it – and there’s the long-standing relationship with Chanel. I remember being at Chanel’s gigantic ‘supermarket’ show in 2014 with Rihanna and Cara Delevingne pushing each other in trolleys up and down the aisles, models wielding chainsaws in the DIY section and carting packets of Coco Chanel Pops around in their baskets. Karl Lagerfeld was riffing on art and fashion and daily life, but in that context it felt like an expression of something bigger.

Horses and the Grand Palais have always gone together; the entrance from the basement is actually called the ‘paddock’; it was made for horses. Regarding Karl Lagerfeld: we started working with Chanel in 2006, and it’s an ongoing collaboration; they are also major sponsors of the renovation. Apparently, Lagerfeld fell in love with the location, the space of the Grand Palais, and especially with the glass roof. He was really inspired by all of the fabulous events held at the Grand Palais in the past: the radical and avant-garde salons artistiques, but also shows about locomotion, mobility, aeronautical machines, all visited as much by the general public as by the avant-garde. When I think about the Lagerfeld sets, I also think back to Monumenta, when artists like Anish Kapoor and Anselm Kiefer were

invited to come up with large-scale installations.

You’re known for bringing an interdisciplinary approach to your cultural programming. You put on a Margiela show at the Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in 1997, when fashion wasn’t readily accepted by museum institutions. You’ve also put on exhibitions showcasing the work of architects and designers like Herzog and de Meuron and Konstantin Grcic. How do you plan to bring this kind of eclecticism to the Grand Palais?

I don’t call it eclecticism; I call it building relationships. Today, more than ever, all of these disciplines are talking to each other and we expect artists to look beyond their own disciplines. Herzog and de Meuron, for example, work with fashion, with sport, with museums; they build museums. I like to use the words of my German mentor Alexander Kluge, who works and writes in the same way as W.G. Sebald, and speaks about the ‘convoy of the arts’ and ‘gardening’. You bring all of these different things together in a garden and then work from plot to plot – that’s how you start to see these relationships and understand them.

That touches on the importance and role of people – both creatives and the public – when you’re creating a space. When Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano were building the Pompidou, it was dismissed as a ‘cultural supermarket’ influenced by the Fun Palace and the ideology of Cedric Price and the Archigram movement, but if that kind of curiosity and social consciousness is placed at the heart of architecture then it attracts a much more varied museum audience, a bigger audience, a younger audience. How much is the role of the audience a consideration when you’re building and programming spaces?

I am glad that you bring this up because finally – finally – we are taking the public seriously, not least as an effect of the pandemic. We miss audiences. At night I am sure that the artworks in empty museums come off the wall, console each other and start to cry, like in André Breton’s Nadja. Curators are starting to think that perhaps it’s not just the collection that matters, but also the audience, especially local audiences, because there are no tourists at the moment. And I’m glad that you mention supermarkets again. One example of taking the audience more seriously is that we have to take museum shops more seriously, so long as we render services as much as products.

‘We miss audiences. I’m sure the artworks in empty museums come off the wall, console each other and start to cry, like in André Breton’s Nadja.’

Museums are also going to have to adapt to us and our new expectations. Like, as you say, the idea of the shop in the cultural institution and what you can express there. I think about what Sarah Andelman did with colette, totally transforming fashion retail, and also Carla Sozzani and what 10 Corso Como brought to Milan, changing its local area. We have Dover Street Market in London and other cities in the world. These places bring together different realities and transform the ways that we think about commerce. Your friend [Italian philosopher] Emanuele Coccia calls commerce the ‘forum of things’. Could you tell us a bit more about this idea of commerce within the Grand Palais or the Grand Palais Éphémère. How will retail spaces influence your planning?

I recently discovered in our archives the inventories of the museum boutiques at the end of the 19th century in Versailles.

What kind of things did they sell?

They sold etchings and posters; they sold photographs, which we now call postcards; they sold books, little booklets, that were purely inventory because the group-show catalogue was a much later invention. We want to try out different things, but the most important thing we can learn from colette, the Vitra House in Weil am Rhein and Corso Como is that the shop needs to be an experience. You need to create an environment for both financial and cultural transactions. I am a great fan of those museum shops that tell little stories. You can start to ‘play museum’ in boutiques; you can teach people to look at things differently. If you put books by Peter Saville next to those of graphic designers working in the Low Countries in the 1920s and 1930s, you tell a story! You want to entice through curiosity. You want people both to buy books and to say, ‘That’s interesting – there is a correlation.’

It makes me think about what happened post-May 1968, and how the Pompidou was influenced by Parisian society at that time. It was a time – and perhaps it is a time now – to envision a different kind of public and to promote the shift from a passive audience to a participatory one. Do you think that museums and cultural institutions can serve as a place of exchange and dialogue during times of flux?

During the 20th century we had times when people were rethinking what an exhibition was and what role the public was playing. It happened in the 1920s, the 1930s, the 1960s, and it’s happening again now. We never took those efforts very seriously, I think. The fact that the Centre Pompidou turned into a more normal institution with conventional separations after only a couple of years is testament to that. Now there are all the questions we have to ask ourselves about governance, staffing, ethical sponsorship, the relationship between private and public, commercial and non-commercial. In all of these questions is a sub-question: what is the role of the public? I think about an expanded notion of culture as something invented by a public executing its interactive rights when it says: ‘I would like to listen to this; I would like to see that; I would like to use an exhibition this way.’ The role of the public is becoming more essential. When you think about rituals in our civilization, the ideal place for rituals in ancient times was the theatre. In the Middle Ages, and also probably the baroque period, it was the cathedral and the chateau, too. And then, at a certain moment, the museum became the ideal place for ritual. But in order to keep it that way, we have to reinvent the museum.

For me, a ritual is an obsession that brings comfort and safety. In this context, it makes me think about huge, non-programmed spaces, such as at Tate Modern, which you were so influential in transforming: those halls and other areas where visitors can do what they want. Whenever I go there with my kids, they’re happiest running riot in the Turbine Hall, while I look for a comfortable chair and a cup of coffee…

Tate Modern is a very good example because it’s an ultra-democratic place. In museums, we are all together, both individually and as a collective. In Tate Modern, in the new MoMA, at the Bourse de Commerce by Pinault in Paris, our museum spaces are invaded by what? By chairs and by tables! We are starting to use museum spaces as something quite different – and we are going to do exactly the same at the new Grand Palais. We want to use museums and cultural infrastructure as a place for encounters. And why does it work? It works because there is little public space left. We feel unsafe in the public spaces that we know, so we have to reinvent the idea of it. We can do that in museums, because they are places that feel both safe and strange.

‘The strangeness of museums leads to other ways of behaving. I see people act differently in museums; they even move differently than in other spaces.’

In the past you’ve also often complained that museums are too big. How do we reconcile their size with the need for intimate spaces?

The museum is a collective space and an intimate space. When you visit the museum, you can easily be alone and isolate yourself, but you can also visit with a group. It’s a socializing space, but it gives you the liberty to choose how to socialize. Woody Allen – maybe it’s a bad name right now – but he said that the museum is the ideal space for meeting people, and it’s true! When you are in a museum, you see strange things; you see works of art that make you feel different. You can be a different person. The strangeness of museums leads to another way of behaving. I’ve seen in my work that people act differently in museums; they even move differently than in other spaces.

Do you think the public will be quick to re-embrace these spaces? Or do you think there’s going to be a longerterm reluctance to engage with cultural moments? You’ve been talking about togetherness…

It’s not a reluctance, but we have to learn how to behave again. We have to adapt to all the situations. You’re interested in design and architecture, so you remember the first lockdown when we saw everywhere in the city interiors and exteriors changed by do-it-yourself architecture. All this tape hanging everywhere, all that cardboard everywhere. Now suddenly we see infrastructure that is inspired by that ephemera, but highly designed. It’s very interesting that the way we look at architecture, both interior and exterior, is completely changing. But we are hesitant, because we are not used to it yet. We have to adapt ourselves.

The Grand Palais Éphémère is going to replace the Grand Palais during the renovation. Temporary structures are often a way to experiment; indeed, you’ve referred to this amazing wooden structure and its space as a testing ground. What is your vision for it?

The Grand Palais Éphémère is almost as large as the central nave of the Grand Palais, so it’s a unique kind of double. But where the nave at the Grand Palais is completely transparent, like a glasshouse, this one is not, because we built it in collaboration with the Olympic Games and while that might make you think of live events, the games are even more media events. So the Grand Palais Éphémère is about 10,000 square metres of floor space that feels like a huge TV or cinema studio. That gives us a way to experiment with projection. That gives us a way to say to our customers, to our collaborators working in fashion or art or ecology, that they can use this space in a variety of really different ways.

Does your programming for this year and 2022 take coronavirus restrictions into consideration?

One of the big advantages of the Grand Palais Éphémère is that you can put a crowd of a thousand people in the space and they’re still socially distanced. We don’t need to put chairs down; people can just lie on the floor, just like they did in the Turbine Hall during Olafur Eliasson’s wonderful Weather Project installation. That means we can offer much more than cinema and theatre; we can do fashion shows, opera, theatre, dance. One of the first things we will do is invite Boris Charmatz to come and dance in that space. He doesn’t use the fourth wall; he makes dance installations where the public can move around quite freely. In the first season we will have lots of live stuff that is currently constrained by the health restrictions and the architecture of theatres, dance halls and opera houses. We are coming back to a time – think of Walter Gropius and Maholy-Nagy’s Bauhaus ‘total theatre’ – when we have to reinvent not just museums but also theatres, cinemas

and shopping architecture. I don’t want to say that it’s an exciting time, but it is an important time.

You seem to have a strong sense of responsibility. Do you feel the weight of executing a vision for these spaces? How do you go about that?

Because of the Grand Palais’s size and layout – and the Grand Palais Éphémère’s the same – it’s a space where we can programme many different activities at the same time to create experiences for many different individuals or groups of people. That’s our economic basis and also the cultural task we have been given. We have a huge responsibility towards these users, visitors and participants. You have to create the best possible conditions for an experience or a set of experiences different to normal life in these spaces. That’s going to enrich us and also the city. We are not alone in this. It all comes down to that famous philosophical question: Who am I, that I am here?