Demna speaks to writer Cathy Horyn about his long journey from post-Communism to future couture, a once-rejected Balenciaga internship and what it means to be a multidisciplinary fashion designer today.

By Cathy Horyn

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Creative partner Dovile Drizyte

Demna speaks to writer Cathy Horyn about his long journey from post-Communism to future couture, a once-rejected Balenciaga internship and what it means to be a multidisciplinary fashion designer today.

To write about Balenciaga is to be drawn back to 1968, the year that Cristóbal Balenciaga abruptly closed the Paris couture house he had opened 31 years earlier. In a report on May 22 that year, the New York Times called him ‘the prophet of nearly every major silhouette that changed the shape of women’: the black taffeta harem dress and cape, the scarf-coat (immortalised by Irving Penn’s photograph of his wife and model Lisa Fonssagrives), the semi-fitted suit, the sack dress, the baby doll, the cocoon coat, and the ultra-simple 1967 bridal gown in ivory gazar with a headpiece echoing a monk’s hood, or, to the writer Mary Blume, a ‘coal scuttle’.

‘No other designer could be so heartbreakingly simple or so irrevocably complex,’ Blume wrote in her widely admired study, The Master of Us All: Balenciaga, His Workrooms, His World. Born in the fishing village of Getaria, in the Basque country of northern Spain, in 1895, Balenciaga was a puzzle in lots of ways – beginning with the fact that he was a foreigner at the top of a French institution, haute couture. He dressed some of the world’s most-alluring and most-photographed women, and yet, as Blume and others have noted, he showed his clothes on the oddest-looking models in Paris. His couture house at 10 Avenue George V was enormously profitable, especially after the Second World War, but he wanted no outward display of commerce on the premises. Hence the pure white salons on the third floor, an emblem of the silence that reigned throughout. (‘In a room of 50 people you could hear the buzzing of a fly,’ said designer André Courrèges, who trained with Balenciaga.) Hence the total absence of luxury products in the street-level windows, which he instead turned over to an artist named Janine Janet, who created eccentric sculptures out of materials such as bark, shells, and nails.

With Balenciaga, everything was mysterious except, finally, the reason for closing. It was the 1960s, the rise of designer ready-to-wear and hip boutiques, and he ‘believed that within his realm he had an obligation to provide leadership,’ fashion writer Kennedy Fraser wrote in 1973, the year after he died. That belief in his authority is the reason his designs look so strong; it’s also why he could not have compromised.

On the morning of July 7, 2021, I arrived early at 10 Avenue George V. Demna Gvasalia, the creative director of Balenciaga since 2015, was holding his first haute-couture show, and I wanted to absorb a moment whose significance went far beyond a debut. Gvasalia, along with the chief executive of Balenciaga, Cédric Charbit, and the Pinault family, which controls the brand’s parent company, Kering, were reopening the house’s historical base, closed since 1968. The salons and celebrated workrooms had been used for storage and offices, and until recently a Balenciaga boutique had occupied the ground floor, with bags and such displayed in Janine Janet’s former windows. These were now boarded up in black. But the most stirring change was to see Balenciaga’s name, in its original serif font, restored to the building’s facade. One reason that great houses survive beyond their founders is the correspondence between the name and a building: Chanel is 31 Rue Cambon (it’s now actually most of Rue Cambon); Dior is its big, drowsy corner of Avenue Montaigne. In Cristóbal’s time, 10 Avenue George V was a phenomenal gateway, but since he apparently left no clear instructions about his name, it was used by his relatives in Spain to market ready-to-wear and perfume, and then sold to a German company. When I met Nicolas Ghesquière at the brand in 1999, it was owned by the cosmetics and fragrance company Groupe Bogart. The archive, run by Marie-Andrée Jouve, was in cramped quarters, and Ghesquière, who began at Balenciaga making funeral clothes for a Japanese licensee, worked out of a studio down the street from Dior. Once Gucci Group (now Kering) came into the picture, the brand setup on the Left Bank, eventually moving its current sprawling complex to Rue de Sèvres. The boutique on George V was simply in the former couture house – that was as far as any mythic connection to Cristóbal went.

I stood for a moment looking up at the elegant letters on the facade and then went inside.

In the past, clients would have entered through the boutique and taken the elevator – Blume, in her book, says it was lined with cordovan leather and ‘patterned on an eighteenth-century sedan chair’ – to the third-floor salon. Owing to structural changes, guests now took a beautiful and ancient flight of stairs, the iron railing distinctively marked at the base by a well-worn carved gargoyle. Was this the original employee and trade entrance, I wondered? I certainly couldn’t imagine Mona von Bismarck or Bunny Mellon hopping up these steps for a fitting.

Gvasalia had relocated the salon to the first floor, but in every key detail – the white-plaster walls, white portières and plush sofas – it was a reproduction of the original. And though less visible, small nicks and water stains had been deliberately added to the decor, to suggest the passage of time. Of course, this is ridiculous. Time did stop here, for 53 years. No petites mains came to work; no heiresses rode the sedan chair. Gvasalia is a master of stagecraft – as we saw in his 2019 power-dressing show, with its blue set that resembled a modern parliament, and in early 2020, as the pandemic hit, with a show that evoked catastrophic flooding – and having explored the aesthetics of political power and chaos, it stands to reason that he would be obsessed with the aesthetics of couture. While the standard practice today among couturiers is to present away from the house, in a museum or dreamscape constructed in a tent, Gvasalia understood the power of drawing on an archetype.

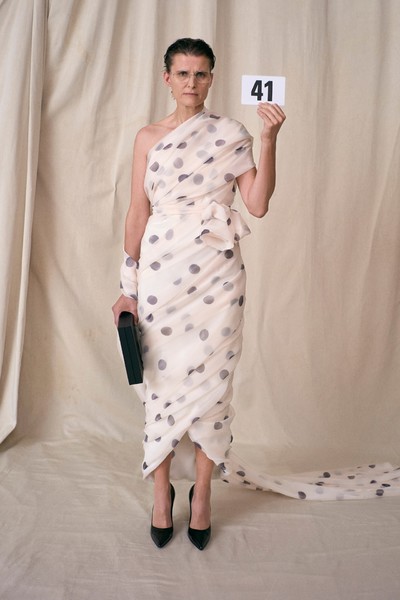

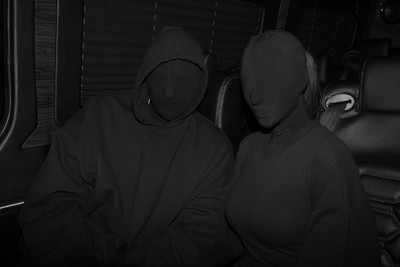

I found my seat and chatted with my neighbours as we watched the scene. Kanye West, in a full head mask, wastalking to Formula 1 driver Lewis Hamilton. NBA star James Harden arrived and took his seat, followed by the rapper Lil Baby. The chattering continued throughout the room and then, without warning – that is, without music – the first model, Eliza Douglas, a Gvasalia favourite, was crossing the carpet in a black pantsuit, and the chattering stopped with the abruptness of starlings. By the fifth or sixth number, also black tailoring and shown on both sexes, the room fell into a deep hush. Kanye was forgotten. The only thing I noticed was how impeccable everything was, how right the clothes looked. Gvasalia had taken the shapes and gestures for which he is known, like oversized suiting and pieces worn off the shoulders, like a trench coat or a fake-fur jacket with jeans, and refined them. A grey hoodie had been given the same polish as a suit. In some styles there was a trace of a Cristóbal design, like his famous 1955 sailor shirt, which seemed to find an echo in a trim, two-piece orange outfit with a stand-away collar. Unable to improve upon Cristóbal’s 1967 wedding gown, Gvasalia said later that he had simply remade it, replacing the cap with an opaque nylon veil.

Modern in form and purpose, the collection was a great argument for why couture matters. First, it proved costume historian Anne Hollander’s theory that one of the oldest sartorial forms – the masculine suit – has still not exhausted its possibilities, that with imagination and superb craft it can look new again. And second, by taking pains with such basics as jeans and T-shirts, it showed that the everyday can be more disarming than a beaded couture fantasy. Vanessa Friedman, writing in the New York Times, called it, ‘a master class in how to learn from the past to get most effectively to the mid-21st [century].’ And Rachel Tashjian, in GQ, wrote: ‘Is it too crazy to think that Balenciaga’s couture show […] might change the world?’ Raf Simons, who saw the show online, told me that Gvasalia is ‘the most modern designer there is right now’.

Raf Simons, who watched the Balenciaga [couture] show online, told me that Gvasalia is ‘the most modern designer there is right now.’

On September 13, Gvasalia escorted Kim Kardashian to the Met Ball, causing a sensation: both were dressed as conceptual silhouettes of themselves, all in black, their faces hidden. If couture was Gvasalia’s ‘coming out as a designer’, as he later characterised it, then the Met indicated a distinctly different turn for Balenciaga. It’s true that the house has dressed actresses from the very beginning – Marlene Dietrich and Rita Hayworth, to mention two – and during the Ghesquière years (Jennifer Connelly, Gwyneth Paltrow), but this was an unprecedented display by Gvasalia, who is modest by nature. Not only was it his first trip to the ball, but Balenciaga made a bigger celebrity strike, dressing Rihanna and Elliot Page as well.

Then, on October 2, Gvasalia took the notion of celebrity even further, with a ‘premiere’ at the Théâtre du Châtelet, as part of Paris Fashion Week. So familiar was the whole set up – the baying paparazzi, the dazzling expanse of red carpet, the classic preening – that it actually took a while for guests to register that the celebrities were the models and, what’s more, some of them were Balenciaga staff, while others were guests who had unknowingly joined the parade. It was genius. And to top everything off, the premiere itself was a specially created 10-minute episode of The Simpsons, made in cahoots with Gvasalia and his team, in which Marge and Homer and the rest of Springfield strutted on the Balenciaga catwalk. I’ve never heard a fashion show audience laugh so hard.

Six years ago, Gvasalia, the founder of a scrappy label called Vetements, was virtually unknown except to insiders. Today, at 40, he has not only completely remade the house of Balenciaga in his vision – ‘it’s my story now,’ he told me this autumn – but he is also leading and inspiring the industry by taking it into fresh terrain. Born in Georgia, then part of the Soviet Union, Gvasalia now lives near Zurich with his husband, the musician BFRND. For the first of two long conversations, we met on the day of the Simpsons show, at the Balenciaga corporate headquarters on Rue de Sèvres.

Photograph by David X Rutting, via @kimkardashian

Let’s talk about the Met Ball. You were the man escorting Kim Kardashian.

Demna: My prom date. Never in my life at a prom, and what a date it was.

She looked amazing in the black version of the 1967 bridal gown. But it wasn’t exactly the same dress, right?

Demna: No, no. We’d worked together on that concept since July. I wasn’t planning to go to the Met, because that’s not something I usually do or feel comfortable doing. But then Cédric talked to me and said, ‘Demna, now you’re doing couture, you’ve kind of opened up the whole thing. I think for this house to grow it’s important that Balenciaga is represented in this way.’ There were a lot of people already willing to wear couture to the Met, before Kim. I thought, OK, if all these people are wearing Balenciaga, I have to be there. I was curious also. I wanted to be there and not be there. Not to be seen, because I have an issue with that. It’s more like a personal psychological issue. [Laughs] And I thought, ‘If I go there I want to enjoy it, so I don’t want to stress about a picture of me that I won’t like.’ And because the topic of the exhibition was American fashion, I kept thinking about that, and for me, it’s a T-shirt. It was so obvious. And then a silhouette being such an important thing – I always work around a silhouette when I do collections – I thought, ‘Why don’t I go as a Demna silhouette? What does it mean? Me as a shadow of myself, somehow.’

That was it. I literally wore to the ball what I wore on the plane to New York. I didn’t change; I didn’t wash or anything. I also liked the idea of effortlessness because everybody gets so overdressed. It’s Cirque du Soleil. We love it, we don’t love it – I mean, it’s amusing, but at the end of the day, it has very little to do with fashion, in my opinion. I wanted to kind of question that. I just slept in my sweatpants all the way to New York, arrived there and covered my face. And that’s my Met look. It was almost anti-think in terms of expression.

‘I wore the sweatpants I slept in on the plane to the Met Ball. I arrived in New York, and just covered my face. It was anti-think in terms of expression.’

And Kim?

Demna: We worked on her look with the same approach. I was, like, ‘If you go in Balenciaga, then we need to do something stronger than you just wearing couture.’ She has created a brand of herself and also kind of changed the notion of how people see beauty and body proportions. And obviously notions of her face. But I was, like, ‘Do we even need to see your face to know it’s you?’ I told her, ‘I think you’re at that point of your fame where we can just cover you head to toe in a T-shirt, and people will still know it’s Kim Kardashian.’ And I love that notion of how strong the celebrity of someone can be expressed visually – in her case, through her body. Kanye was supposed to go to the Met, but for various reasons he couldn’t. I think Kim wasn’t comfortable being alone with a covered face. You can’t see so well through this thing. I just said, ‘OK, I’ll walk with you.’ That’s how our prom date happened. Some people at first thought I was Kanye – and you know I like pressing those buttons. I really had fun on that beige carpet. [Laughs]

Did you stay for dinner?

Demna: I stayed for dinner. I mean, I could hardly get to the table; someone guided us. It was really fun. We took a picture with Sharon Stone, and I didn’t know it was Sharon Stone because I couldn’t see – I thought it was Jane Fonda.

That’s hilarious.

Demna: With these kinds of events, it’s all people you see in movies, and I was happy not to see all that, I have to say.

Let’s talk about your July couture show. Even people who know your work well were absolutely spellbound. They didn’t expect what they saw. Why did it get that response?

Demna: There was an emotional charge to the whole thing – for me, too. As creatives, this is the biggest challenge. We need to charge our work with an emotional message. For me, it was so personal – the love and the effort I put in it. I think it was felt through the collection; I didn’t have to explain it. But it was also like a coming out for me as a designer. Of course, there were a lot of people there who knew my work, though maybe not in depth. Yeah, the hoodie, oversized tailoring, streetwear, sneakers – all those things – but I’m not sure all those people really knew me as that kind of designer. So that was important. I think I told you when we spoke after the show that I felt so at peace. I felt like, ‘I finally expressed who I really am as a designer, and people saw it and understood.’ Not just the fashion insiders and historians, even from Kering and Balenciaga, there were some people who were actually surprised when they saw the couture. I showed them the collection on boards, and I found their reaction amazing somehow. They were, like, ‘Oh, my God, that’s a completely new thing. It makes so much sense, but I didn’t expect it.’ I felt really bad after those kinds of comments.

Because they underestimated you?

Demna: I realised they hadn’t seen me for who I always knew I was. I think I came to Balenciaga knowing, deep inside, that I might one day have the possibility of doing couture. Which I couldn’t do at Vetements. I mean, there would be no reason. In a way, Balenciaga was just such a perfect match for me as a designer. I realised in July that somehow I had wanted that, without daring to accept the idea, and when I felt that a lot of people who know me personally and know my work were surprised… I mean, I had to spend a couple of sessions with my coach talking about that, because it hurt me. Even though they gave me compliments, I was still like, how could they not have known? Did they also put me in that ‘sneaker-guy’ box? I needed to be out of that box, I have to say, and that’s maybe what couture did. It really liberated me, in a way that was completely natural. I love doing sneakers and I love doing streetwear – I went to the Met in sweatpants – but there is a different type of elegance that I am about.

Of course there was streetwear – a hoodie, jeans, a T-shirt – in the collection but all perfectly made and fitted, along with your tailoring. That’s what struck me – how you had refined and refined the Demna things and at the same time cast them in the world of Balenciaga, with his sense of line and precision. The off-the-shoulder styles worked into the fake fur, worked into the orange suit. You could clearly see the links to Balenciaga’s aesthetic, yet it was hardly a pastiche or an homage. It was something entirely new.

Demna: It’s been six years. As you mentioned, I have evolved. I always question myself; I think I’m my biggest critic. It’s actually positive for a creative to do that because you should never stay in your comfort zone. The off-the-shoulder thing was something I did before I came to Balenciaga, all that swaggy attitude in clothes. It was an idea that came from the street. When I looked at Cristóbal’s work, I thought, ‘Hmm, he kind of did the same, but in a very different context, in a different time.’ So I found that link and started working on it. Opening the neck, swinging the pieces. The silhouettes have evolved a lot since my first collections for Balenciaga. I can still make a thing better, reach another level, and not be afraid of leaving my comfort zone. Couture was a manifestation of this exercise. Also, I had one year.

The lockdowns gave you more time.

Demna: We were working on the collection before the pandemic started. And then once I realised we wouldn’t be showing in July 2020, everything changed because I had more time to reflect. At first, the collection was very much referencing the archive; it was too much into Cristóbal’s work. I realised, ‘OK, I have more time now, and I’m not 100% liking this.’ I didn’t want the collection to look like a historical tribute, even though it would have been good. Like the wedding dress at the end, which was that symbolic thing. I could not have made it better than the original. So I had more time to infuse myself into the collection, my vision. It’s my story now and I don’t want to try to be Cristóbal Balenciaga, which I could never be. But I can be myself. This is also one of the reasons why I decided to show couture no more than once a year. With everything else that we do, it would be absolutely

inhuman otherwise. Also, very limiting. The Federation [Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode, which governs French fashion] doesn’t even want us to be on the official calendar because

we’re not showing twice a year. Those idiots – I mean, I am so angry with them. I’m, like, ‘How dare you try to impose these rules from the 18th century? Do you really believe that designers today, with everything they have to do in their houses, can deliver quality like that every six months?’ It’s offensive, I find.

Do you need to be on the calendar?

Demna: No. They think it legitimises everything; it legitimises nothing. People will come to see my couture. I feel it shows the mindset. I also discovered that Balenciaga himself left the calendar because he had problems with the Federation. It makes more sense not to be included.

‘It is political and social commentary on what is happening around us. I want to go into what a trench coat actually represents, its social status.’

Who first approached you about the Balenciaga job?

Demna: Actually, I was on my way to the ANDAM fashion contest. My brother, Guram, wanted Vetements to take part in every possible contest, so we’d have more cash flow. [Laughs] And obviously we didn’t win any of those contests.

I remember seeing you in your stand at the LVMH Prize cocktail in 2015. Virgil Abloh was across the aisle. That’s funny, considering…

Demna: Yes! Somehow I have a bit of nostalgia about that, but we didn’t win; it was very humiliating. We didn’t win ANDAM either, but when I was entering the building at ANDAM, a person was standing there, someone I didn’t know. It was Lionel Vermeil, who was then the PR at Balenciaga. He approached me and said, ‘I know who you are. I want to talk to you about something. We’re looking for a creative director for one of the houses owned by Kering. And we’re interested in talking to you about that.’ I don’t know why but I knew instantly it was Balenciaga. It was a feeling in me. I remember, in the car later, saying to my husband, ‘I’m pretty sure he means Balenciaga.’ And a day after, I read on a news site that Alexander Wang was leaving. So I just put the two things together. Lionel doesn’t like me saying this, but he was the first person who kind of recruited me. He saw that link between my approach to the body – he saw that Cristóbal cocoon reference in my bomber jacket – and for that I will be forever grateful, because not a lot of people see it even today. He kind of presented the idea to the people at Kering.

Then I had this meeting with François-Henri Pinault in the old Kering offices. I had to be very secretive, almost pretend I was somebody else so people wouldn’t know. I had to go through the parking lot so people wouldn’t see me. I was, like, ‘Oh, my God, I’ve just come out of the gay club and I’m driving to the Kering headquarters.’

For many people, you wouldn’t have been an obvious candidate. And Ghesquière had proven hard to replace. How did you wrap your mind around that?

Demna: I studied; I prepared myself for that meeting. Of course, I knew about Cristóbal’s iconic work, but I didn’t really know so much. I knew more about the Ghesquière period. In fashion school,

everyone wanted to be an intern at Balenciaga, myself included. I tried for menswear, but they didn’t take me. I went for an interview and, like, five minutes later, they said, ‘No, we’re not interested.’ So I needed to research Cristóbal as a couturier, to understand if I had a link. You know, I had a job already and that was a moment when Vetements was growing. I felt that if I did the Balenciaga job, something would need to trigger me. I watched this documentary about him on YouTube, with his family members talking about him. And I realised he was a plastic surgeon of clothes. He would cut into a garment, open it, and it would change the whole posture. The magic tricks of Cristóbal. I saw that and I felt this is exactly what I do. Not with the same attitude, but I could feel that connection. Then I could also feel the connection through his personal story. He came from a modest background, the religious upbringing, being gay, not being accepted. I thought, these are all the things that link me to this person whose legacy is so massive in terms of possibilities. I simply could not not do it. Also, I was doing Vetements as my project, my reaction to the whole fashion establishment. I still loved doing it, but I always saw it as ‘my project’. I didn’t see myself as Karl Lagerfeld, at age 70 or 80, still doing that bomber jacket in a gay club. I wanted to move on, and Kering helped me to do that.

Was reopening couture part of your conversation with Pinault in that interview or during your first year as creative director?

Demna: No, absolutely not – it was the conversation I had with myself. The responsibility of this new era at Balenciaga was so scary for me – and definitely unknown to them – that the whole couture thing just stayed as a voice in my head. ‘Maybe one day, if you’re good enough’ – me being my father’s voice in my head! – ‘you may want to talk about that.’ Then it came up two years ago. I thought, ‘OK, it’s all great. I’m enjoying doing fashion, making upside-down parkas, but I need something else for myself.’ Actually, it was more about me being happy as a designer rather than making them happy. Obviously I wanted to honour the Balenciaga legacy but that wasn’t my primary

desire. That was about not wanting to fall out of love with fashion.

You brought such prestige to Balenciaga with the couture. The house is once again on the same level as Chanel and Dior, and maybe even a little more interesting because of your approach. I remember wondering during the show whether Pinault appreciated this.

Demna: I think he did. I first talked to him about couture maybe two years ago. We have these annual design meetings when we talk about the next steps for the brand. In one of those, I said, ‘I want to do couture’, and they loved the idea. I immediately felt supported – by him, by Cédric. I didn’t have to go and convince them that this was the right thing to do. On the other hand, they have always given me carte blanche. They said, ‘If you feel this is the right thing to do…’ It wasn’t, like, ‘Oh, yeah, we want to do it because it’s going to bring Balenciaga to a different level.’ Maybe they thought that, I don’t know, they just gave me the feeling that if you think it’s the right thing and it’s part of your vision, then you should go for it and we’ll support you. I have to say that has made my life here so much easier. I’ve had this carte blanche since the beginning. Nobody told me, ‘Make a sneaker.’ When I did make the sneaker, they rolled their eyes a bit. But they knew that, with me, we weren’t going to follow the rules necessarily. They didn’t ask me to do elevated streetwear. It was just, do what you think is right.

Did you have to open new ateliers and find skilled workers?

Demna: All of that. We started by recruiting the team, because we can’t use the same atelier for haute couture that we use for ready-to-wear. It’s a very different dynamic. In ready-to-wear, we have

three to four fitting sessions on each product; that’s the maximum I can have. In couture, I have 10 sessions, and there are bigger gaps between the sessions so that the atelier can actually do the work. We needed two different structures for that. I don’t remember which house closed its couture around that time, but people said, ‘Oh, we can get workers from there.’ And I said, ‘Wait a second, we don’t need to do that.’ Of course, if they’re good people, sure, but we can also have people grow from our existing teams. There are so many young pattern-makers in our ready-to-wear who are absolute fanatics about what they do. To me, they were the perfect candidates to move to couture. We could let them grow and not only have a couture team of people with 40 years’ experience at Yves Saint Laurent or Dior, who have their own rules. Tradition is great, but if you want to see a future for this type of craft, then the teams need be at least under the age of 40. I’m sorry, but otherwise what’s going to happen in 20 years? Who will know how to do that armhole?

Azzedine Alaïa once told me the same thing. He was expanding his atelier and he took some people from Saint Laurent’s couture workrooms when they closed. But he said they had been doing the same kinds of clothing for years, so hadn’t acquired new methods.

Demna: And it’s hard to have them grow with you, because it’s like taking someone with knowledge and trying to reshape that. Whereas I have people who know me from ready-to-wear so I knew they’re so crazy about what they’re doing that they would spend nights trying to figure out how to make the collar of that orange jacket. I mean, I think that was the most complex thing we, or at least I, have ever made at Balenciaga. That guy was 29 years old, and that was his challenge. We did have to take some people from outside, too, especially people who sell couture. We have this person, who is in her late 60s or 70s, who worked for many years at Saint Laurent couture, then at Gaultier couture, and now she’s here. She has her carnet d’adresse. Sometimes she looks in it and says, ‘Oh, this person I didn’t contact because she might not be alive anymore.’ She actually told me this – laughing – because some of these people she knew 30 years ago. But the beauty of couture at Balenciaga is that we don’t want to only have that client book. We have approached our ready-to-wear customers who spend tons of money and suggest maybe they don’t need to buy that much ready-to-wear, and instead just buy one couture trench. And those people came to the salon and bought.

How are the sales?

Demna: Well, it’s ongoing. It’s not like ready-to-wear with only one week of selling. We had 27-year-old twin brothers – I don’t know from which country – come and order about 12 looks, including women’s looks, because they want to have them in their collection. We had a lot of men and a lot of people under 35, like daughters of some of the people in that address book. So far, from what I’ve heard, it’s really rejuvenated.

What’s been popular?

Demna: They wanted the jean jacket with an attitude and the trench. I think they did sell a crazy embroidered dress to someone in the Middle East. But, I mean, those will cost $300,000. For me, it was clear: if couture is only that, it will never survive. But the denim jacket and the vicuña turtleneck, these are the pieces that people bought. Of course…

I thought about stealing that vicuña turtleneck after I touched it…

Demna: The jeans. Shirts. Tailoring. That’s what was important to me. How do we put couture in the context of now? Of course, the robe and the coat that Rihanna wore at the Met, but they’re special red-carpet pieces. Who has a life like that?

I remember covering couture in the late 1990s. The clients were still a huge presence, but then they went away. They were active but less public. Yet, with such tremendous wealth in the world, why wouldn’t someone buy couture?

Demna: Exactly. I knew I wanted to create a new niche, one that does not exist. Couture is about magnificent embroideries or a Chanel jacket, of course, but I wanted to open the conversation to a new generation that, yes, has financial credibility and who also gets it. I’m very curious because in November we’re having an installation in China with all the couture pieces. It’s such an important market for us, but people from Asia could not come to couture in July, so we’ll recreate the salons there. I’m curious to see the reaction. They’re very modern in their approach. They’re not looking for embroidery.

Will you do fittings there?

Demna: Yes, but the problem is our people can’t go because of the length of the quarantine, so we created a team there coached by people here. There are 10 fitting rooms in the salon that we’ve prepared. Customers can try on things and order.

High fashion has always thrived on an image of exclusivity. Couture, with its specialised knowledge, its privileged access, and prices, is a symbol of that. Yet you’ve been so much about inclusivity, by taking streetwear seriously and showing your clothes on a very diverse cast in terms of physical beauty. I’m thinking of the Spring 2020 ‘parliament’ show, for example.

Demna: I can’t wait for you to see tonight, because that’s the maximum I’ve done in terms of diversity. Not just in terms of gender or origins but types of people. It has never been as good as tonight.

Why does that matter?

Demna: I think it’s what makes you a modern brand today, especially with our approach to couture. One major difference between couture now and back then is that Balenciaga wouldn’t let certain people into the salons. There was a woman at the door who said, ‘No, no, you are not intellectual enough’, or whatever she thought. It was so exclusive, very snobby. Today, it’s the extreme opposite of that. I’m thinking now about how I can make couture even more accessible. Because you still have to come to Paris, or wherever this installation will go. You have to make an appointment with a vendeuse [saleswoman]. It’s not that accessible yet, and for me it has to be fully inclusive. I’m even thinking we’ll open some couture store-showrooms where people can just walk in and see things and potentially order. I’m talking to Cédric about this because it’s obviously an investment.

But part of the allure of made-to-measure Paris clothes is the experience, the incredible quality and attention to detail. I’ve had clothes made for me at Chanel and Alaïa, and there’s nothing quite like it. I’m not sure I’d want to go to a storefront…

Demna: You can have access to any of that, but there are a lot of people who would not, though maybe they have the means and the desire. Even if you have a couture store, it’s the same thing that you would have in the atelier – this whole made- to-measure treatment. For me, it’s how to make it more inclusive, not something only for industry insiders and rich ladies and celebrities, who often don’t even pay for it, they just expect it to be done for them. How can a regular paying customer have access to what I think is the closest you get to perfection in clothing? Maybe the store is not the answer. I was in Getaria this summer and I saw that Cristóbal’s first boutique was on the first floor of a building, like an apartment. It was a salon, basically. I thought, Wow, that’s an amazing idea. People come to a private apartment.

‘Nobody told me, ‘Make a sneaker.’ When I did make the sneaker, they rolled their eyes. But they knew that, with me, we weren’t going to follow rules.’

By the way, what’s going to happen to the boutique on Avenue George V?

Demna: It’s going to be a modern part of the building. In Cristóbal’s time the windows were used for an artist’s installations. That’s what I want to do with them, too. But rather than just use the shop

windows, it’s going to be the whole floor. During Fashion Week, it could be open for the public to come in. Not as a retail space; just for display. Maybe there are couture pieces or other products.

It fascinates many people how versatile you are as a designer, able to take on big themes like political power in one show and catastrophe in the next, and at the same time make a crazy parka or experiment with 3D printing for tailoring. Lagerfeld, as productive as he was, did not have that split in his focus. I can understand why you once said you view couture as a way of slowing down or ‘cleaning up’ your mental process.

Demna: Did Lagerfeld meditate?

Actually, he worked alone in the mornings at home. That was essential in his routine. He worked in his bedroom, sketching and sketching or talking to the studio about the day’s work. No one disturbed him.

Demna: I have a complex of inferiority right now. [Laughs] To wake up and sketch, that is crazy. But maybe because I’m married to a musician, I wake up with, like, bass pumping. We’re like an after-

hours club at breakfast. Literally, this morning the neighbours knocked on the door because it was too loud. But, yeah, that’s crazy to wake up and sketch. Maybe I don’t ‘live’ fashion in that way, but I have made that space in my life. Before noon, there is no fashion in my life – then there is no limit. But you mentioned wanting to ‘clean up’ – that I understand. It’s probably what I wanted to say with couture and the way it felt. Also the silence. It’s my way of meditating through fashion. Slowing down, making some distance, being in silence. Couture also came at the right moment for me, professionally; I feel like it really gave me another decade in fashion. You know what I mean? I love doing fashion, but sometimes when you have all these deadlines, it can be too stressful. It can become too much like a machine, and then you lose interest.

I can imagine how couture would give you huge satisfaction.

Demna: It somehow gives me durability of interest in fashion. Because it’s the only thing I’ve ever wanted to do. I don’t want to be trying to channel Helmut Lang or any of those other amazing designers who at one point said, ‘OK, I’ve had enough now; I’m going to do something else.’ I’m not sure I can ever do that. But I always question whether it’s something I want to do always. There are so many things I disagree with about the industry, but during the pandemic I realised this is what I do best – clothes. Now I’m trying my hand at set design. I’ve been doing it at Balenciaga, but now we’ve done it for Kanye’s Donda [album] launch, which was an amazing experience. I like doing it. I’m going to try directing BFRND’s next music video, probably. But then, again, I go back to clothes. This is my zone. This is what I love most, and I don’t want to give myself a deadline for it. I just want to stay hungry and excited about it, and this is what couture did.

Tell me about your design process. Do you first work out ideas at home in Switzerland and then go to the team?

Demna: I’m a loner in general. I need to be alone often in order to connect to myself. That’s how I start every season, mostly at home, where I start editing the ideas. My ideas come as lists, and lists of lists, and a huge number of visuals that I keep on my phone. Then I archive the images in boxes: boxes for collections, campaigns, concepts. Then twice a year, I basically go through all this stuff and edit it, whatever triggers excitement in me. It’s very random. I’m a voyeur; I constantly take pictures or screenshots of things. The season for me is really two collections. For example, what we are showing tonight and what we’ll show at the end of November. It’s one season, essentially.

So it starts alone in my atelier at home. I need that time in silence to focus and to work things out. Then I have a meeting with my smaller team. It’s Martina, my right hand, and a few designers, and we just brainstorm. After which, we launch the general research so the whole design team is involved. Then we edit everything, because we end up with so much stuff. Editing is a big part of my job. Cutting, pinning, and editing. I love it. I love editing and collecting the information and then translating that into ideas. But also the process of scissors and pins.

Yet it often becomes a form of commentary…

Demna: It is political and social commentary. In my research, I’m not really interested in having a picture of a deconstructed trench coat. I want to go into what this trench represents, whether it’s social status or a comment on what is happening around us. I feel that being a voyeur lets me absorb all of that. It can be subconscious, not necessarily thinking, ‘Oh, I need now to talk about refugees.’

It is a big topic in my mind, because it’s part of who I am and I’m trying to deal with my whole personal story. It’s just there, and it’s going to translate into my aesthetic and into the collection. The

subjects that matter. And some of them are so strong I wouldn’t even want them to surface in the work, because they can be overwhelming or maybe send the wrong messages.

For example?

Demna: Gender. I find it very tricky sometimes. Because maybe for me personally it’s still an issue, sexuality and all those things. What does sexy mean? Have you seen the sexy Demna collection? [Laughs] I don’t think that actually happened yet, and I think for a reason – maybe I’m a bit afraid of trying to understand what it means to me. And being vulnerable enough to let people see that. Because my sexy might be scary to someone, myself included. Obviously the ‘parliament’ show was political commentary. I’m trying to be informed. I think it would be completely ignorant not to be interested in that.

‘I sometimes find gender very tricky. Maybe for me personally sexuality is still an issue. What does sexy mean? Have you seen the sexy Demna collection?’

Yet few designers show an inclination to do this, never mind the capability. It’s partly what makes fashion feel a little disconnected. In the past, Gaultier did amazing shows related to gender and sexuality. Radical for their time.

Demna: Also, I don’t want it to be too literal. For example, the walk-on-water show – I think it’s one of my favourites in terms of set-up and message and it just happened to appear before this pandemic horror started. I referenced the Bible and Jesus walking on water. Do we believe it? If we believe in God, then maybe we do. I was questioning those things. What is reality? With all the conspiracy theories about a flat earth, and I don’t know what else – we don’t know anything. So Jesus might have walked on water or there might have been a platform underneath. But then we gave the show this extra charge by creating the smell of petrol, like a world drowning. This whole arena drowning in greed; it’s disgusting. For me, the parliament show had the same level of disgust – about European politics and what happens in Brussels.

When I was 17, I worked as a translator for a Georgian news channel for foreigners. It was in English and I spoke the best English by Georgian standards at the time, so I could translate the news. And I have to say, when you have insight into dirty, corrupt politics in a post-Soviet country at 17, you get hooked on that a bit. It’s also part of me, through that kind of commentary.

You’re the only prominent designer from a former Soviet state, so your perspective is already different.

Demna: Strange, though, I have to say. This business is so about decorative dreamland creations, and that’s what I’m absolutely uninterested in. It’s a turn-off just to decorate things. You know, my view is not satirical; I want to do things in an artistic way. I see a show as an artistic installation, similar to what we did, though at a different level, for Kanye’s Donda tour. There was this messaging that was subliminal, that was very personal but also very poetic and aesthetic. We can talk about things happening in the world, but I also want to create that aesthetic link. It has an impact, but it’s also about beauty – and that’s what fashion is. 60 percent of Balenciaga’s customers are under 35, and because these people are so connected, it matters to them, too. It triggers something.

The pace of change in just the past few years is truly breathtaking, and how differently young people perceive things…

Demna: I spoke to a few journalists recently and I felt so much negativity. I was frustrated and I told my husband about it. Maybe fashion has become a bit constipated. I’ve been questioning this whole thing about a show. Does it make sense? We want to be at a show but, on the other hand, it’s kind of boring. This is why I’m trying something else tonight, you’ll see. It’s just trying. I’m not sure it works or not, but I want to try something else. I just want this to be fun. But the change needs to happen, and it’s a moment.

Well, you’re very nimble.

Demna: What is nimble?

Flexible, quick. Many designers are stuck in their comfort zones, lack ideas or are afraid of going off brand message.

Demna: Even here, this season, when I told them that there wasn’t a show, they were, like, ‘What is it?’ I was, like, ‘It’s a premiere.’ I didn’t want to do a video, because we did a feel-good video in May and people loved it. There was no product in it. I was, like, ‘Why don’t we do something that is just fun?’ It was a dream: The Simpsons. The whole humour and tongue in cheek, and also the kind of romantic, beautiful part of The Simpsons. I’ve always loved it. My husband has a Bart tattoo on his arm and when I met him in person, I thought, ‘That’s a sign. From above. We have to come together.’

I was told The Simpsons never do stuff like this. They don’t do specials with brands. Then we contacted them, and they were, like, ‘Hmm, we like Balenciaga.’ Actually, the parliament show was a trigger. I mean, the creators of The Simpsons are really not into fashion at all, but they could see that there was something behind the clothes.

We had been working on the film for a while and then suddenly Fashion Week was back and I’m, like, ‘Uh, what do I do with this episode that has no collection in it?’ It’s Springfield goes to Paris Fashion Week. I’ve watched it 10 times and I love it still.

So there is this fun moment, which I feel we need. I wanted it after couture, which was so monastic. I wanted something that would break that. So I said, ‘Let’s do a premiere. And let’s use the ridiculous red carpet as the actual show.’ We wanted to dress everybody [in the audience], but that was logistically difficult. So now we have 65 people who are going to arrive there tonight.

During my first meeting with Demna Gvasalia, I did not probe him for details about his plan for a red-carpet premiere followed by a Balenciaga episode of The Simpsons at the Théâtre de Châtelet that evening, and, in hindsight, I was glad I didn’t. Nothing could have prepared me, and others in the audience,for the surprise and downright sense of fun. And it sprang from the purity of the concept – having a group of sophisticated people ‘walk’ on the carpet, unaware that their gestures and self-conscious posing were being recorded and shown on a giant screen inside the theatre, to the delight of those already seated. And of course, who is more guileless than the Simpsons? Early in the special episode, Homer, wishing to buy a dress for Marge’s birthday, pens a letter to the Paris house: ‘Dear Balun, Balloon,Baleen, Balenciaga-ga.’ The collaboration with the creators of The Simpsons began in April 2020, and as Al Jean, an executive producer and writer, told the New York Times, Gvasalia and his team ‘were definitely our match in terms of, to the last detail, making sure everything was perfect’. To date, the episode has been viewed nearly 9 million times on YouTube.

For our second conversation, on October 5, Gvasalia and I spoke in the white salon at 10 Avenue George V.

So you go from creepy shows about political power and hints of disaster to The Simpsons. I wrote down your character’s response to Marge’s sad little letter, when she returns the €19,000 dress: ‘This is exactly the kind of woman I want to reach!’

Demna: It was hilarious. And she just wanted to wear it for a day. I find that the most beautiful thing.

Again, you are able to work on multiple levels, from the rarefied world of haute couture, which also incorporated mass-market looks like jeans, to one of the most popular shows on TV.

Demna: Which is just about fun. It’s also a critique, especially the red-carpet part. I enjoyed mixing my assistant Telly with my usual Balenciaga models, who most people think are not beautiful, and then having Juergen [Teller] there and Offset. What is that? Is anyone a celebrity just because they’re posing on the red carpet? The Met Ball was quite an experience, even though we had started working on our show before. Still, I could see the impact.

It’s probably how most people see fashion – on celebrities at events such as Cannes. It also reminds you of how human the desire for beauty and glamour is; it’s hardly limited to celebrities.

Demna: A lot of people from my team and my models came up to me at the party afterwards and said, ‘Oh my God, Demna, thank you. This was amazing, I felt like a star.’ I thought, Wow, that’s a Marge Simpson moment. It’s so psychological, right? One of the guys who we cast from the street – who has never been in a luxury store in his life – was, like, ‘Where did you !nd me? I feel like I’m Brad Pitt now because everybody comes up to speak to me, just because my picture was taken on the red carpet.’ This is why I love being able to do what I do today at Balenciaga.

Here’s my picture from the red carpet the other night. [I hand my phone to Gvasalia, who bursts out laughing.]

Demna: That’s amazing! I hadn’t seen that. Wow!

Of course, I didn’t know that everybody was inside the theatre and looking up at the screen and laughing at me. All the photographers, who I know from the runway, were yelling, ‘Cathy, Cathy’, so I played along.

Demna: The funny thing, which nobody knows, is that the soundtrack for the event was all fake. We actually used a recording from last year’s Met Ball. Sometimes you can hear somebody yell, ‘Beyoncé’, but nobody noticed. I loved that, because even though the soundtrack was not synchronised to our red carpet, it still worked. It was another detail that no one knew about, apart from BFRND and I, but it underlined the unimportance of that in a way. Beyoncé had nothing to do with this event.

I’d like to talk about your family and early career. What did your parents do for a living?

Demna: My father had a car wash and a garage. He’s a car mechanic, my dad, and he’s as obsessed with cars as I am with clothes. He was lucky to have that business, tuning cars and so forth, in 1980s Soviet Georgia. My mum was a housewife. When I was born, she was 17.

Is your mum Russian or Georgian?

Demna: She’s part Russian and part many other things, like French, Jewish, Albanian. But she’s mostly Russian and my dad is Georgian.

And Guram is your only sibling?

Demna: Yes, but we lived in a kind of communal place with all my cousins and grandmother. A kind of a kibbutz, which actually shaped me in many ways. There were three houses where my dad’s three brothers lived with their families, and then my grandmother and us. Everybody would have breakfast together. Literally, at any time, anyone could just walk into your bedroom. There was very seldom any space of privacy, and I always suffered through that because I was a bit of a loner. I wanted to draw, and I didn’t want to play football or dig around in the car with my dad. I just needed my space and it was very hard to gain it in that kind of place. I’m still working on how it impacted me, but I think it did a lot. This is why I always felt like an outsider there, even in this big family. I would go into the garden behind the house and just sit and draw there. I think I had a bit of an issue with being social with people, even with my cousins and uncles. I had a happy childhood, but I always dreamed about something and it was not part of where I grew up, really. I didn’t identify with this very Georgian way of being altogether all the time; Italians do that, too. You go on holiday with the family. Everything that’s yours is mine; whoever wakes up first is the best dressed. It was a bit like that.

When did you first know you wanted to leave?

Demna: I did have this feeling very early on, and I think it was more linked to my sexuality, because I knew I could not fully be myself in this environment, in my family, even in that country. The country still has huge issues with the LGBTQ community. It’s a nightmare, actually. I cannot go back there for those reasons. I think I was eight years old when I knew that I was gay, and I sensed that was a problem and I didn’t know how to deal with that. That’s when I began daydreaming, ‘OK, I’m going to have to study well, so that one day I can leave and be myself.’ I didn’t realise that coming to Europe didn’t necessarily mean that you will be accepted. Very early on I did express this desire to my parents. I was also really good at school.

‘I was eight years old when I knew that I was gay. I sensed it was a problem but didn’t know how to deal with it. That’s when I began daydreaming.’

Which subjects?

Demna: I was not good at maths; I had a private teacher for that. But I was good at literature, languages, biology. In a Soviet school, you have to study all of that. So I was always telling my parents that one day I would be ready to fly off. They weren’t really thinking of leaving the country themselves. But when I was 16 or 17, I was really looking into options, like being an exchange student or looking for asylum. I resolved to go to Holland and just say, ‘I’m gay.’ [Laughs]

But you stayed and earned an economics degree, so I imagine you have a good understanding of economic theory.

Demna: I had to study all these theories that I hated, like the basis of capitalism and international trade. I hated it all back then, but I have to say now that it was good for me as a designer. It probably

shaped me as a different type of creative. I’m very product-oriented, for one thing. I’m interested in what I can deliver to the consumer, what the consumer actually desires. So there was a silver lining in it, but I hated those four years there. I was writing in my school notebooks, and on the back I was sketching clothes. It was this bipolar way of life. When I told my dad I wanted to study fashion and become a designer, he was, like, ‘This is not a job. You can do it on the weekends, but you have to work in something else.’

Because he didn’t know about fashion designers or how clothing is produced?

Demna: I think it was a combination of those things, and also in his macho Georgian mentality that fashion was something girls should do. And I think he was afraid: ‘Oh, he wants to do fashion, so he’s definitely gay.’ [Laughs] But I have to say I’ve been drawing clothes since I can remember. The first present I ever got was a set of colour markers, from my grandmother. In one week there was nothing left in those markers, because I just drew like a crazy person. That was my bunker in a way, where I would find my private space – before I knew that fashion design was an actual job. I thought it was done for movies. We didn’t have that information in Georgia.

At some point your family moved to Düsseldorf…

Demna: My father started to have an import-export business with Germany, so he was there more and more. Then my parents sort of realised that neither I nor my brother wanted to stay in Georgia, because there were no prospects for us. Basically, the whole family moved, including my grandparents.

Was emigrating a difficult or strange experience?

Demna: For me, it wasn’t that dramatic. I was already 20 or 21; I spoke German. I spent three months in an immigration camp, with all the other people. You’d get a number at seven o’clock in the morning and then go register for this or that office. When you emigrate, you have to go through so many steps, like your health registration or your job credibilities. It’s quite hardcore. I was also the person in my family who spoke the best German, so I would have to interpret for them. It felt a little bit stressful. Also, Germany for me was the place from where I could go elsewhere; I didn’t plan to stay. My economic diploma was recognised there, so I could have gone and, I don’t know, filled out bank transfers for a living. And that’s what my parents dreamed about: ‘It’s amazing. You can work in a German bank!’ I would have died of misery and depression after two years. That’s when I started researching about where I could go learn about fashion. I needed to go to school.

How did you choose the Royal Academy in Antwerp?

Demna: It was a friend of mine – my former English teacher in Georgia – who said, ‘Demna, you should do what you want.’ I couldn’t afford Central Saint Martins, and she sent me a French newspaper in which there was an article about the best European art schools. It mentioned the tuition for each school. The Royal Academy was €500 a year because it’s a state school. I thought, I have to try and go there.

You didn’t know about the Antwerp Six?

Demna: I knew nothing. I didn’t even know where Antwerp was. And then I got in. I remember Walter Van Beirendonck sitting in front of me during the entrance interview, with other teachers. I didn’t know who Walter was, and he said, ‘So, tell us what you know about the Antwerp Six?’ I only knew about Dries Van Noten. I really had no knowledge. No Margiela, no nothing. I think Walter was quite pleased with me for not knowing who he was. It was kind of a destiny because I failed the interview, they told me later, but passed the drawing and fashion part.

So, you’re in Antwerp at an exciting time in fashion. Gucci Group and LVMH are buying up houses like Balenciaga. Margiela is still working. Galliano is remaking Dior. Helmut Lang is still active. That’s a lot to absorb, never mind the legacy of the Antwerp Six. Where was your head at the time?

Demna: I don’t think I realised any of that then. Of course, being in Antwerp, you’re in the hotspot of Belgian fashion. Linda Loppa was still teaching at the Academy; I was in her last year there, so I was lucky to have her as my tutor. But I don’t think I was really aware of the dramas that were going on in fashion. I didn’t have any idea yet of what I wanted to become. I knew that I wanted to do clothes and that I had to find myself. I did not find myself while I was in Antwerp, I realised later; it was really research, but very naive research. I was open to direction. Very often in a school like the Academy you can be directed by your tutors in a direction that might not necessarily be yours.

My experience with Linda was one of the best experiences that I had. She looked at my project at the beginning of the year and asked, ‘Would you wear it?’ I said, ‘Actually, no. It’s like a costume.’ And she said, ‘Do you know anybody who would wear it?’ I was, like, ‘OK, I have to change my project.’ She opened my eyes to how important it is that you shouldn’t just make costumes. Fashion is not that; it’s not a dreamland. We can argue about that, but for me, it’s important that if I make something, it’s destined to be worn by somebody. That was probably the most important thing I learned during my four years in Antwerp. Just picture somebody wearing your designs.

At school I went with the flow – and the flow was like kayaking in a crazy sea. There was no direction, really, and it felt very dangerous. I was worried. It was so much money, which I didn’t have. I had to scrabble here and there to survive, because making a collection, buying the fabric, was quite difficult for somebody like me. How am I going to pay off all this? Where am I going to get a job? At the same time, the Academy is quite competitive. They read your results in front of the whole school. It’s judgement day. With every jury, some people were out.

I learned a lot about making clothes, because I didn’t have money to hire pattern-makers and seamstresses, which you can do now, if you have the money. I literally didn’t sleep at night, trying to learn how to make a jacket. And, at the end of the day, what I learned about myself was that I didn’t need those rules and special measurements. I could do it by eye. I could just draw a pattern. A friend of mine, who was my tutor in pattern-making, said to me, ‘I don’t get how you do it. It’s against the rules, but it works in the end. So is it good or bad?’ And I was, like, ‘As long as it works, I don’t care.’ But I had this eye. And I’m still very hands on when it comes to fittings and working on shapes.

I have very positive memories of Antwerp, but also I remember this hunger. I was so bulimic for all this information. I needed to absorb it all – about Raf Simons and Margiela and Dries, all very Belgian. I have to say I didn’t know much about other things in the fashion world.

After that, Walter was my first job. He saved me. He liked me but we had a lot of, like, you know, disagreements. By the third year of school, I had my idea: I wanted to do all black and a lot of tailoring. And Walter didn’t like that. We had moments when it was, like, ‘Oh, God, he’s going to throw me out of here.’ But it was his way of guiding me; we’re still friends. At the time, he was working for a brand, a bit of a Belgian Ralph Lauren [Scapa Sports], and he wanted some younger designers on his team, so we could make something fun, which didn’t work out. But I had a job. I had the job before I graduated, thanks to Walter. I stayed for less than a year because I felt, ‘OK, I’m going to

shrink into this commercial mindset.’ You know, making your sketches on a screen, when I needed to cut and drape.

Were you applying for jobs in Paris?

Demna: Everywhere. Paris, New York, Milan. I think I sent out around 90 portfolios. But most of the graduates did that, too. I never actually got anywhere with those applications. I got a few commercial consulting jobs here and there. I started to think, ‘OK, I can never get a job in this industry.’ I was also not socialised – all that coming to Paris Fashion Week, hanging out with people. I was not this sassy boy who went to fashion parties or tried to get into shows. I did go to Raf Simons’ shows twice as a dresser, and to Veronique Branquinho as well. I wanted to see how the backstage was. I told Raf about it later.

I was frustrated with these commercial jobs, which actually paid my bills, so I thought, ‘This cannot be.’ I have to keep drawing. And I kept drawing these looks, thinking, ‘This is how Margiela should be.’ By then, I had learned a lot about deconstruction. It spoke to me a lot. So I thought, ‘OK, I’m just going to send Margiela my portfolio.’ Maybe it was my economics mind, but I thought, ‘They need to open it, they need to look at it’, because I know often in companies they get things they don’t even bother to open. I thought the packaging was important, so I put it in a pizza box from a restaurant called Don Giovanni. The CEO was called Giovanni, too. That got their attention – and it was not a fresh pizza box! I was, like, ‘Let’s just go for it.’ And it really worked. They called me and said, ‘We want you to join the team. Can you move to Paris in 10 days?’ I lived in a friend’s apartment, on the couch, for three months until I could find an apartment. But, for me, it was OK. The door opened suddenly to Paris.

Margiela himself had retired from fashion at that point and the house was owned by Diesel. What shape was the Margiela archive in, if there was one?

Demna: It was a nightmare. It was full of moths; things were on the floor. It was hardcore, but there was a lot there. As a young creative, I didn’t have a chance to work with him, but being in the archive – with everything smelling of naphthalene – I loved that. It was such an intimate moment for me. Seeing how the shapes were made, how things were destroyed and something new made from them. That whole mindset liberated me. I would never have dared to cut up an existing jacket to make a new jacket before that. I would have been, like, ‘Oh, no, you can’t do that! You need to construct it.’ At Margiela, I learned to work three-dimensionally. It gave me my understanding of what I could dare to do with clothes.

Did you ever meet Martin?

Demna: No, but I wrote a letter to him to express my gratitude. I really did stay at the brand to save the legacy, with good intentions.

You told me that once.

Demna: But it was so hard because I was a nobody there. I stayed two years, until I kind of indirectly got fired. They offered me another part of the collection that I was not interested in, and then I just left and never went back. I was just angry because I wanted to give so much to that house and somehow nobody wanted it.

I thought, ‘OK, I’ve had this experience; now I need to understand how a big brand works.’ Then a headhunter called me and told me they were looking for someone at Vuitton, with Marc. I thought, ‘Oh, God, not my thing at all, but why not?’ I made a big project and Marc loved it, apparently, and then I got my job at Vuitton. I have to say, for designers, working at Vuitton is kind of a dream. You have great resources, super conditions, a good contract, a wardrobe budget. It was amazing.

‘The Margiela mindset liberated me. I’d never have dared cut up an existing jacket to make a new one. I’d have been, like, ‘Oh no! You can’t do that!’’

And Marc was doing some brilliant collections.

Demna: I learned a lot from him. On an aesthetic level, it was perhaps hard for me to connect with him, but that’s OK, that was my job. For example, he wanted a perfecto [leather jacket] embroidered with feathers because he saw a Cher movie on the plane. You know how he is. [Laughs] I fell absolutely in love with Marc as a person, as a visionary. Sometimes he would call his assistant to bring the karaoke suitcase and then he would sing Barbra Streisand. I was, like, ‘Now I see how you can have fun being a designer!’ On Saturday night with the red-carpet show we tried to do that for the public, and at work I sometimes think, ‘This is too corporate. I’m not singing karaoke, but let’s have fun. Let’s make this fitting into a party.’ That’s something I learned from Marc Jacobs.

When you started Vetements, with some friends and your brother, it was in reaction to big brands. I remember our first meeting, in the Vetements showroom, when I told you I thought it looked too much like Margiela. Vetements was about other things, but I didn’t know if the Margiela influence was a sign that you were still finding your own way.

Demna: I think it was very much about that. I remember you said that. A lot of people drew this parallel, also because we marketed Vetements as a group of people who used to work at Margiela. To

be honest, at the beginning, Guram wasn’t there. I was there with two other people, both of whom now work with me at Balenciaga. Both used to be my assistants at Margiela, and they left when I left. While I was at Vuitton, I realised I needed to have my own creative expression. I had put some money aside while I was working at Vuitton, so I was OK. That’s how Vetements started. We were, like, let’s do something on the weekends, because we still had our day jobs. We were a team. We were three people exchanging ideas, sitting and smoking Gauloises and drinking wine the whole night. And brainstorming. That’s how we came up with a heel made from a lighter. It was three o’clock in the morning. We had a shoe shape and we were, like, ‘What do we do with the heel?’ And we didn’t have heels to try. Today, I have 20 different heels to try. There was the lighter: ‘Well, there you go. That’s a shoe.’ It was this very spontaneous thing. I really didn’t plan for Vetements to become a brand, but then Guram came in, he needed a job, and we said, ‘Let’s see if we can get some customers.’ That’s how we started.

I remember going to the show at the Dépôt club in Paris.

Demna: We’d already done two collections. I remember a friend, Lars, texted me – he’s obsessed with you – and said, ‘You have to see that Cathy Horyn mentioned you.’ You wrote that you’d taken a motorcycle to get from one show to another…

True, with a driver.

Demna: Lars was, like, ‘Can you imagine Cathy Horyn took a motorcycle to go to a gay sex club to watch a show?’ I was, like, ‘Probably mission completed by now.’

And of course, once you got into the Dépôt, which is tiny, it was crammed. Kanye was there. And the models were literally sweeping past your knees.

Demna: We didn’t have a backstage until five minutes before. We had to put a curtain up. But that’s also the beauty of it.

Everybody craves those moments – and we were seeing something new. I mean, there were distinct overtones of Martin Margiela, but I recall François Lesage, who worked with the greats, telling me that designers belong to a lineage, like a family style tree. Alaïa was in the Balenciaga line; that’s clear from his shapes. And Raf has always said that there would be no Raf Simons without Helmut Lang.

Demna: I think acknowledging that is important. I hate how this industry rips off each other, often in a bad way, and then pretends not to see it. For me, it was quite a struggle from the very beginning. My connection to this enigmatic heritage of Margiela, which I learned on autopilot, was still so strong at the beginning of Vetements. I think it was my anger coming out about what I couldn’t do there. Of course, if they had heard and seen me, I probably wouldn’t be sitting here today. And there would have been no Vetements. When you have to suppress your ideas, it has to come out somewhere, and it came out with that ‘project’, which was how I looked at Vetements. It was almost a means of self-therapy. And this is why it was hard to explain to you, or anyone, back then why there was this parallel to Margiela – because it was that.

‘After that ‘parliament’ show, a British writer said, ‘Detestable – without hope.’ I love that. That reaction is exactly what I hoped for.’

I want to return to the ‘parliament’ show. It seemed a turning point for you. For one thing, you’d clearly put your personal stamp on Balenciaga, through the tailoring, the cast – who are as odd-looking in their own way as any of Cristóbal’s – the uncanny feelings. Is it comic or serious? After that show, a British writer said to me, ‘Detestable – without hope.’

Demna: I love that. That reaction is exactly what I hoped for.

I thought the show was funny precisely because it considered these serious, omnipresent figures, these politicians and bureaucrats. I know you have spent half your life in the West, but I wondered if growing up in a former Soviet state gave you a special insight into this reality?

Demna: I do think there is a link to my upbringing and how I was taught about the Western world and capitalism in general, from a very critical point of view. I remember seeing a Coke can for the first time and thinking it was a nuclear bomb. They really brainwashed us into being suspicious and critical of all that. I guess that’s something that stays with you. For that show, I looked at pictures of Angela Merkel, for example, and the style of her suits. We used the same photographer who made Merkel’s election pictures for our campaign.

People sometimes say, ‘Are they laughing at us?’ Or, ‘Balenciaga is so cynical.’ And it’s not actually that at all. We’re putting it out there because it feels relevant. It felt relevant to have the models walk on water. We did this whole video-tunnel show [Summer 2019] – one of my favourite set designs – that created this feeling between real and not real.

And now you’ve done something equally ambitious but playful with The Simpsons.

Demna: I need always to be surprised. I need that moment of, what the hell is going on? For me, Saturday was a bit of that. But it’s also what’s next? I’m never going to do a red-carpet thing again, but I need to do something else that will have a different intellectual, emotional charge; something that will matter, too. That’s where I complicate my life, I have to say. I do it because I love it, but then it becomes always harder. But then I always have this here [gestures toward the salon]. I feel, OK, couture anchors me once a year.

I’m very curious about what you’ll see in the December show. I’m trying to time-travel now, to bring the influences that I love in fashion, like the 1990s, when people used to dress up for shows. But there is always an area where you can go next.

With Gvasalia, everything is always more complex, more surprising than one might at first suppose. The 1990s show became a full-on video production directed by Harmony Korine over several days in mid-November in Paris with an audience of extras decked out in 1990s gear and a backstage filled, typically for that time, with cigarette smoke. The concept was ‘the lost season’ – Autumn 1997, when the House of Balenciaga did not produce a collection. The designer Josephus Thimister had just departed after five years as creative director, and Ghesquière had not yet taken over. So this was Gvasalia’s very imaginative take on that missing season, in an era when shows were still small, people dressed up, and smart phones unheard of. And, no, the collection – released digitally on December 8 – was not intended to reflect on Thimister’s contribution or anticipate Ghesquière’s. ‘Not at all,’ Gvasalia told me. ‘I did what I love about the 1990s.’

You’ve mentioned your husband during our conversations. Many people know him through his music as BFRND. How did you two meet?

Demna: I met him on Facebook, actually. I saw the music videos he did with his garage band back then, and I love music. I love what he did, and I felt that I needed to tell him. I texted him and he texted me back, and we started our exchange basically about music. He didn’t know what I did. He wasn’t so into fashion. We got to know each other first on the phone and on the Internet. This was the end of 2015, and we met in London in 2016, the day after my birthday, on March 26. I have never been so nervous to meet someone. It’s like when you know something is going to happen. I was so nervous, and then he walked in, and I kind of lost it. I knew that this was someone who would change my life. He came to Paris three days later, and he never left.

My husband saved me in a way because he showed me how to love myself. Which I struggled to know before. You need to love yourself first to be able to love someone else. That I learned thanks to him. It’s our wedding anniversary today; we’re going fora romantic dinner.

You’ve lived in Switzerland for a while, near Zurich. What prompted that move? Was it partly for tax reasons.

Demna: Actually, I was looking for safety. I had a lot of problems here in Paris. It’s a very xenophobic place to live, in a way. When my husband and I got together, we didn’t want to live in Paris. It’s OK for work, but I don’t want to live here. I also like the mountains – I really need the nature and the snow. Basically, Switzerland was on the list for those reasons, and also the safety. God knows, what’s going on in Europe politically. And taxes are lower than anywhere else in Europe – that wasn’t the primary reason, but it was important.

Do you like living there?

Demna: I don’t like being in Zurich and we’re planning to move. We realised we need to be in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. We speak French at home, and we’re thinking one day about having a kid. We’re looking into moving near Montreux. But I do love living there, the proximity to everything and the amount of nature.

Finally, what advice would you give to young people, living in a city or town that is not a conventional fashion hub, and who don’t feel safe to be fully themselves?

Demna: That’s a hard question. If I look at myself, having lived in those kinds of places, I never tried to blend in. I always accepted who I was in a way that was sometimes dangerous for me, but it made me happy. And I think that’s the most important thing. You have to accept who you are and not be ashamed of that. Nobody should be able to tell us how we should be.

A recurring motif in Demna’s story is leaving: leaving the Soviet world for the West, leaving his father’s expectations of a suitable career for the dream of fashion, leaving one design job for a better one, and of course, leaving France for the security and quiet of Switzerland. He also expresses a wariness of staying too long in fashion, as though he knows it will almost certainly lead to parody – a once-hot designer ‘still doing that bomber jacket in a gay club’ – and he talks in earnest about wanting to direct other creative projects, like a music video. Yet the thought that I had during our sessions was that Demna has only now, with this remarkable year, truly begun to feel like the artist that he undoubtedly is. I mean, he has finally experienced that incredible satisfaction that makes all the nonsense and all the hours worthwhile. That’s what the people in the George V salons and on his comic red carpet understood: a great artist was in the house. No, you get the feeling that Demna is only just beginning.