For Venice Beach native Eli Russell Linnetz, fashion is an unretouched snapshot of 1970s-tinged ‘dude culture’.

By Andrew Bolton

Photographs by Eli Russell Linnetz

For Venice Beach native Eli Russell Linnetz, fashion is an unretouched snapshot of 1970s-tinged ‘dude culture’.

In America: A Lexicon of Fashion, the current exhibition at the Met’s Costume Institute in New York, is an ambitious overview of American fashion, from Claire McCardell to Marc Jacobs to Heron Preston. Among the vitrines devoted to the grand, defining designers of the past eight decades, stands an outfit by Eli Russell Linnetz, or ERL, the 30-year-old designer, photographer, and multitalented creative.

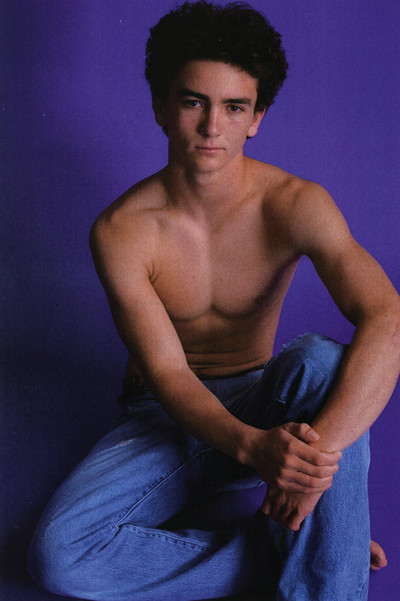

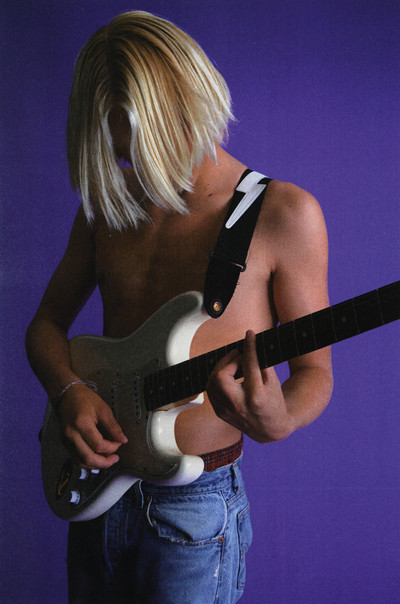

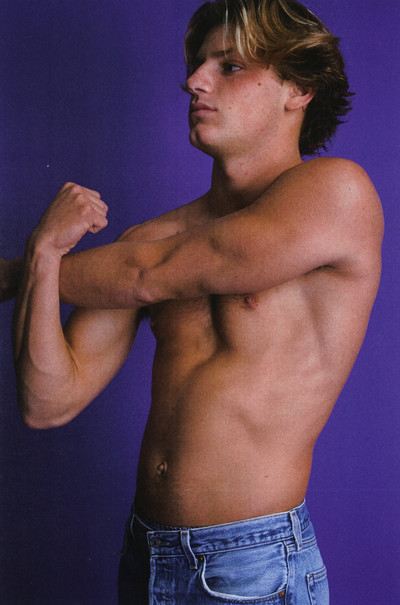

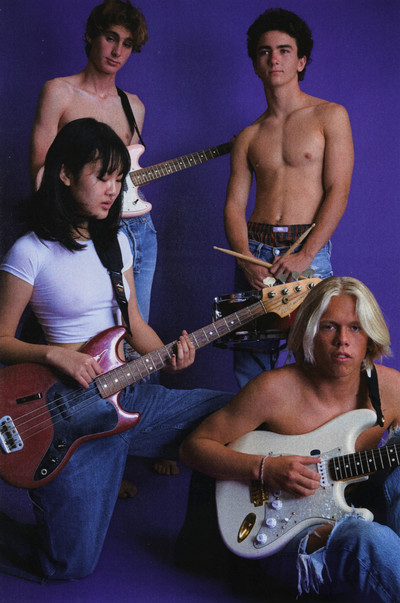

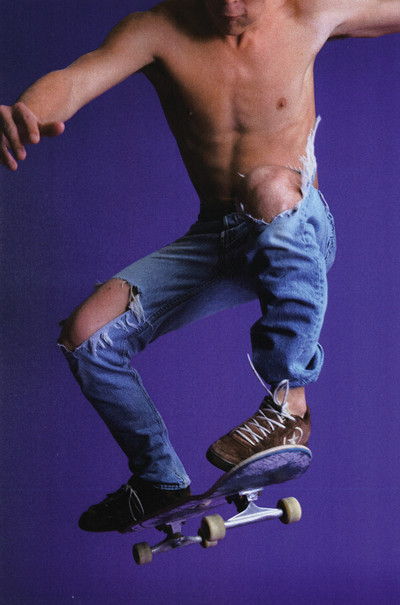

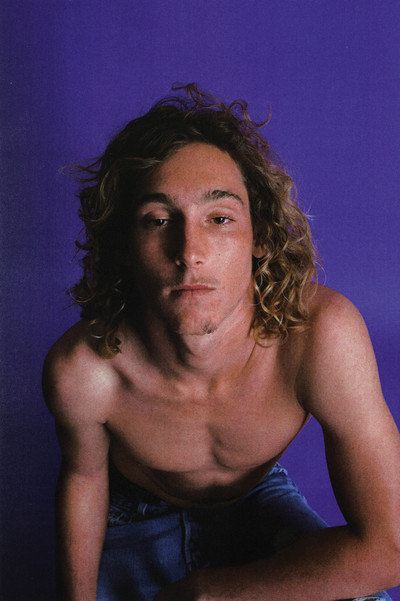

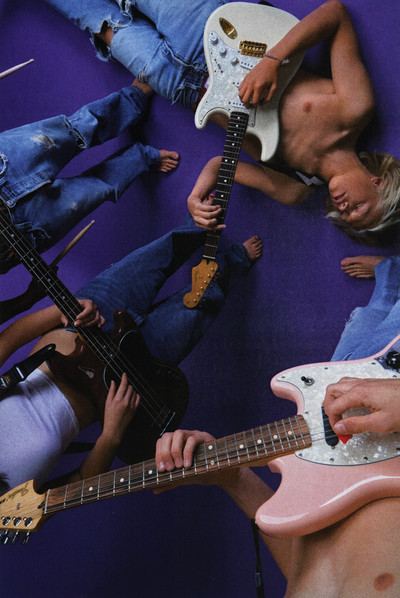

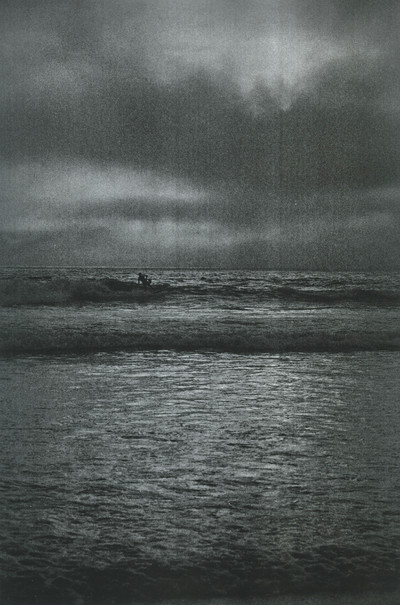

Deeply rooted in his native Venice Beach, Linnetz creates work that evokes an off-kilter fever dream of 1970/80s America, as captured through an unretouched, Polaroid haze that makes real his otherworldly tapestry of influences. It’s a distinctive vision – tapping into a collective unconscious born of Hollywood, optimistic visions of space travel, and classic sporty Americana – that becomes a vivid tribute to 20th-century US soft power, mapped onto a bold, yet flawed view of masculinity (less Bruce Weber or Men’s Health, more Sean Penn’s loveable stoner character Jeff Spicoli in Fast Times at Ridgemont High).

The story of Linnetz’s career is as oneiric as his work: a child actor on the red carpet aged 10, he was working for David Mamet at 15, before beginning a bewildering string of collaborations, directing music videos for Kanye West, designing stage sets for Lady Gaga, producing music for Kid Cudi, and writing songs for Teyana Taylor. When his work caught the eye of Rei Kawakubo and Adrian Joffe, who were in Los Angeles to launch Dover Street Market, Linnetz began working with Comme des Garçons, launched his ERL label, and entered the fashion world. Based in his Venice Beach studio, Linnetz is a kind of fashion auteur: he designs the clothes, does his own styling, runs his own casting, and takes his own photographs. In conversation with Andrew Bolton, the celebrated Wendy Yu Curator in Charge of the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the mind behind In America, Linnetz talks sweat, innocence, authenticity, and sending a thrift-store quilt to the Met Gala.

Andrew Bolton: When I was working on the In America: A Lexicon of Fashion exhibition, people kept asking, ‘What is American fashion?’ And it was so hard for me to answer that because what they expected was a very reduced, essentialising definition. There are 100 ensembles in the show and each one defines American fashion, so there are 100 definitions in the exhibition. If someone asked you that question, how would you respond?

Eli Russell Linnetz: I feel like the answer is ‘nothing’. Even personally, I was never trained as a designer; I studied screenwriting and opera in college. I don’t even think of myself as a designer per se, but rather as an artist almost desperately floating through the world, grasping at things around me. It is not really my job; I am just presenting what I am attracted to, very much like a curator. It’s almost weird that I have fallen into this. I feel like I am in the Manchurian Candidate, like in the morning someone calls me and says a code word and then I design those clothes every day.

Andrew Bolton: People always call you the ‘multi-hyphenate’ and I always think that somebody who is truly creative has different sorts of outlets. You’ve done fashion, art direction and photography, which represents a more contemporary take on what creativity is today.

‘I was never trained as a designer; I studied screenwriting and opera in college. I don’t even think of myself as a fashion designer per se.’

Eli Russell Linnetz: I love going to archives and collecting things from around the world. I see myself as more of a researcher. I went to Michael Jackson’s personal archive and they had all these amazing drawings and paintings that he had done throughout his life; they were so incredible. We only ever see a small glimpse of someone in their work and I feel like that with my clothing: I do so many things that the clothing is almost an afterthought. I work on it 15 hours a day, sure, but it feels like I am simply living my experience of the world.

Andrew Bolton: Tell me more about the things you worked on prior to designing.

Eli Russell Linnetz: I started out when I was 15, working on Broadway for David Mamet. I just sent a cold email and he was like, ‘Come and show up on the set.’ When I did, he was like, ‘You’re really smart; come back tomorrow.’ So I started on Broadway and then I went to USC for courses in screenwriting and opera, and while I was working for David Mamet I started working for Kanye, so I made all these music videos. And then everyone was like, ‘Will you direct my tour?’ So I started doing tours for Kanye and Lady Gaga, and then people were like, ‘Can you take photos?’ Then fashion came, and from that I met Adrian [Joffe] and Rei Kawakubo who I know you have worked closely with. They really took a chance on me. That is what I admire: that relentless following of a vision. Every day you have a reason to quit doing something, but you keep doing it, over 50 years.

Andrew Bolton: What Rei and Adrian really do is seek out singular visions; they look for people who have these very particular approaches and views of the world, which you clearly do. I got to know your work a bit late – I think it’s your third collection that’s in the exhibition – but when I looked back I saw the consistency of your vision. Another thing that struck me is about the myth of American fashion being non-narrative-based, not about storytelling or character – you are a prime example of that not being the case. Have your experiences with screenwriting and photography had an impact on your approach to fashion? Is that your initial inroad into a collection?

Eli Russell Linnetz: I will not dress someone in something that I don’t believe they would actually wear. Some of the commercial teams I have to interact with ask if I can show more of the pieces, but that makes me nauseous; I physically can’t do it. I am so lucky to work with Adrian and Rei, because they support me whatever I decide. My whole team is just me and one assistant: I do all the casting, and every day I am either researching or out on the streets trying to cast people. I photograph all the collections myself, as well. From day one, before I design anything, I think about what those final photos will look like and work backwards from there, thinking of the storytelling and characters.

Andrew Bolton: Do you approach it more as a movie director? Is part of that due to growing up in Hollywood and Venice?

Eli Russell Linnetz: One million percent. I would call myself a director over a designer. Even when I do a stage for Gaga – I did her Vegas residency – I imagine myself as a director. Growing up, I used to have dinner at Steven Spielberg’s house or have Shabbat there – it can’t get more LA! I have been forced to do my own thing and be my own person. I see myself as archiving the world around me and the things I love. Like the quilt I made for A$AP Rocky at the Met Gala; people had such a hard time wrapping their head around the idea that I had found the front of the quilt. It actually belonged to this great-grandmother, but I couldn’t track down who she was even though I researched for months to locate where the fabrics and the prints had come from. Then the Met Gala happened and people were upset that I hadn’t made the front of the quilt myself, but I was like, ‘No, that’s the amazing part!’ People have such a specific idea of what fashion is, but I was just putting things from my world onto the red carpet. It’s that clash and conversation that’s so interesting to me.

Andrew Bolton: I read that you incorporated boxer shorts and your dad’s bathrobes into the quilt. The front is the original quilt and the back is all the additions?

Eli Russell Linnetz: Yes. The front is this amazing bubble quilt that I bought for $25 from a thrift shop; I designed the back and found these amazing ‘memory quilters’ in Boston to make it. To begin with, we scanned the whole quilt and tried to make reproduction prints on dead-stock 1970s cotton, some of it sun-bleached, but halfway through that process, it just didn’t feel real to me. There is this Martin Margiela approach to recreating things from thrift stores, but there is an authenticity to what I do and I felt it was unpretentious just to use the thing and say where I’d found it.

Andrew Bolton: You used the quilt as a metaphor for fashion and American fashion’s different identities. Jesse Jackson has talked about how the quilt is a metaphor for the different experiences of America, and I felt that it was so clever to use its original form and add your own memories. In a way, it is a diary of two different people – the grandmother and you – that you put together in one garment. How do memory and autobiography come into your own collections?

Eli Russell Linnetz: I don’t try and think too much about my past or my future. When I started my fashion line, I had worked with celebrities and giant musicians for so long, I was losing my grasp on reality. So I cleared up this space and I just sat there until I started filling it with things that I was collecting. Piece by piece I started building this story, almost building up a world from scratch, because the world I was leaving behind was too chaotic. Of course, now I have to interact with the same people I was trying to escape! I see myself as a collage artist. I really spend all my time researching; that is what I love to do – to discover forgotten things. I don’t know if I’m brave enough to explore my own past, but I do love diving into archives and finding little companies that went defunct. My new obsession is this wedding-dress maker, Jessica McClintock. I started researching and every single piece I loved said ‘McClintock’ and I became obsessed. She started in the 1970s; I believe she made Hillary Clinton’s wedding dress. I love going down these rabbit holes of Americana. I don’t like exploring myself, but I love a rabbit hole.

‘I imagine myself more as a director. Growing up, I used to have dinner and Shabbat at Steven Spielberg’s house – it can’t get more LA!’

Andrew Bolton: You do tend to gravitate towards a 1970s aesthetic. This may be completely unconscious, but when I began looking at your images, a German photographer called Peter Berlin…

Eli Russell Linnetz: I love him. I have his book.

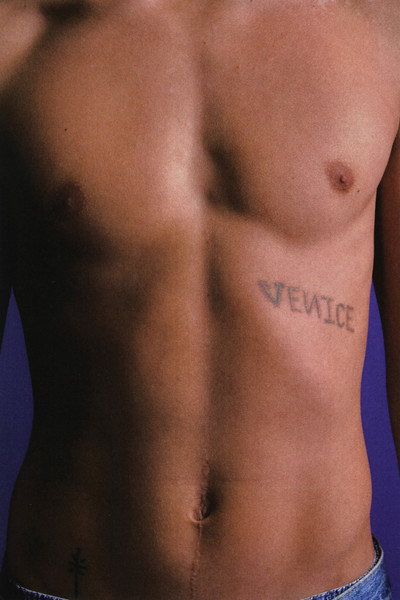

Andrew Bolton: When I look at some of your work, I see Peter Berlin because there is a fetishisation of youth culture and the body, and an underlying homoerotic sense…

Eli Russell Linnetz: Did you stuff the mannequin’s crotch at the exhibition?

Andrew Bolton: Yes, we did! That was so funny, because when the dresser first dressed it, I was like, ‘I think we need something else here.’ It went bigger and smaller, but then we got the right proportions.

Eli Russell Linnetz: Everyone was like, ‘I love how the crotch was stuffed’ – they really got that. That attention to detail was awesome.

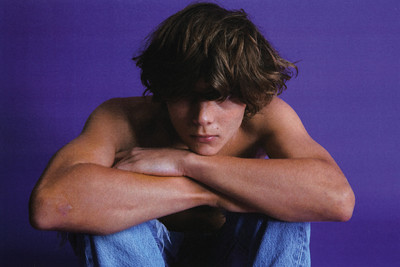

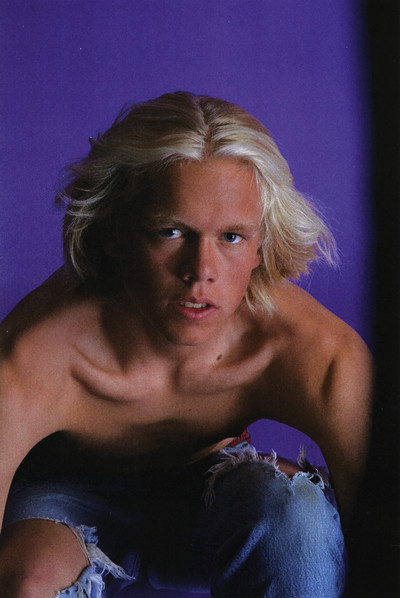

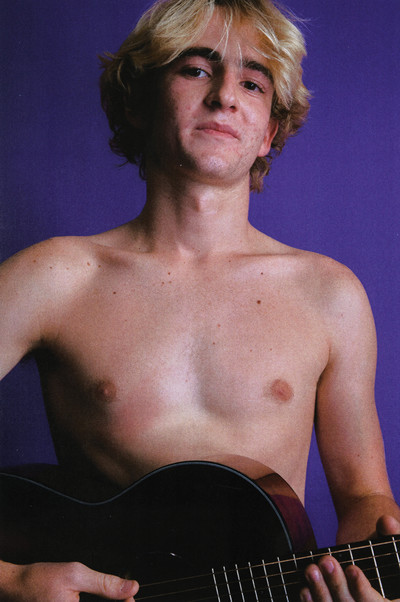

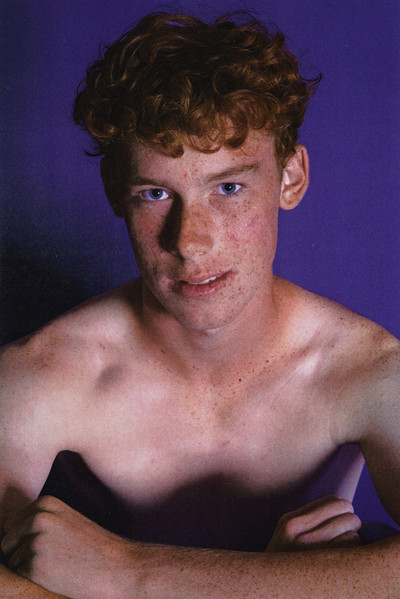

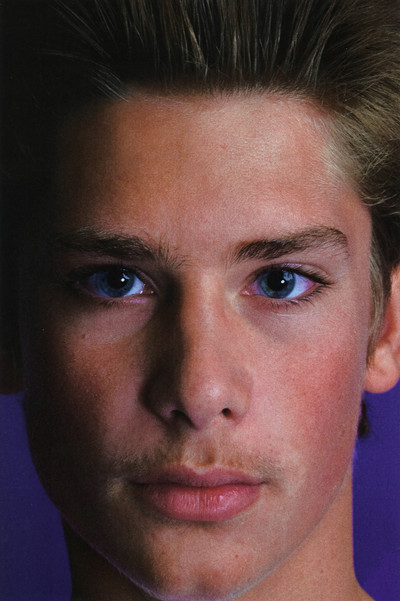

Andrew Bolton: People talk about dude culture with your work and there is so much to unpack with your images: the sweat stains, the unwashed masculinity that you seem to be fetishising. To me that speaks of self-discovery. There is both an innocence and experience in your images. It’s the same tension Peter Berlin used to play around with – that age when you are experimenting with your body. Are these stereotypes of masculinity and particularly American masculinity in your consciousness when you construct the images?

Eli Russell Linnetz: It really is unconscious. When I do a collection, I research and research for months and obsessively think about the characters. Then for it to be successful, I just let it unfold by itself when we get on set. The casting is the most important thing. Someone can take a good photo, but if the casting isn’t right, what does it mean? And if the casting is right but not in the right outfit… It is even harder if you have two people in the same shot – if you don’t believe they can be together then the whole idea of the world is broken. I pick people who can tell the story and I don’t do any retouching. I let them be themselves and it becomes this wild emotional dance between us where we are pushing and pulling about what they are wearing, and their trying to make sense of the shoot. We shoot for two weeks, every day, like filming a movie. I can take 20,000 photos for these look books and then I have to edit it down to like 50.

Andrew Bolton: They read as single-frame shots, and then come together. That is what’s so great about it; each image has a really complex narrative to it. Like Spike Jonze’s advert for MedMen with those dioramas that read as individual shots but put together become a story. That is how your work comes together. I read somewhere that it took four years to find the guys cast for the spring collection, to get the specific look you wanted. Where did you find them?

Eli Russell Linnetz: I travel around, to Orange County, hanging out at the surf spots. A lot of these people are local kids I met or who went to Santa Monica high school, where I went to school, or they are just younger brothers of friends. It’s very organic, but it’s almost like hunting for gold because once I find someone, then I use them for years. You can’t use someone from a modelling agency; there is something more powerful about these people who have so much natural self-confidence.

Andrew Bolton: You believe in them more, that is the end result. A model who is perfect in every way lacks authenticity, while you designing the clothes, doing the casting and styling yourself means there is an authenticity that comes across very powerfully. We believe in these characters because they are being themselves.

Eli Russell Linnetz: Going back to the sweat and stuff, all the people I use are athletes, surfers and wrestlers. We spend weeks doing this, so we are looking for these micro-expressions that communicate many things at once, including innocence and masculinity.

Andrew Bolton: It’s like someone has worked out and then thrown the clothes on the floor and just put them back on the next day, so they are sweat-stained, filled with testosterone. ‘Micro-expressions’ is such a nice phrase – that’s why your images have so much potency, individually and collectively. What I am hearing is that a lot of that process is spontaneous and organic.

Eli Russell Linnetz: It really is. I obsess about certain details, then just let the rest happen. Like, I wanted to sell the underwear pre-washed and the factories thought I was insane. What I am trying to do out here in Venice Beach is so far removed from the high-end production that fashion has become, from just trying to make things for money. Yet the second people start noticing you, they are like, ‘Use our models from these big agencies.’ Then they want you to make videos, but I will not do video content. I went to the extremes of filming – the worst was filming a McDonald’s commercial in Shanghai. I have to create a place of control and when you film, there are so many elements that give people an opportunity to judge. What I am trying to do is pure expression, and I love the idea of just capturing a moment in time on a single frame and letting people read into it. I don’t feel the need to explain everything.

Andrew Bolton: It’s an old-fashioned approach, but as a result there is an authenticity and purity to it that makes it compelling. It makes me think of the film I Am Love where the house was the main character – how much is Venice Beach a character in your storytelling and work?

Eli Russell Linnetz: I don’t really have any rules other than to ask myself at the end of designing everything, ‘What does this say about Venice or skating or surfing?’ My fantasies are so limitless that I feel like people need something to hold on to. It has gotten so crazy because I have the sunscreen fragrance, suiting, men’s, kid’s, women’s lines – I’m only on my third collection and we are doing 300 styles! But I make sure Venice Beach is in every garment.

Andrew Bolton: I love the way you have created a vocabulary and continue to keep refining it, like Azzedine [Alaïa] or Rick Owens. You do it in a different way: they return to design motifs; you return to characters and to a place. That is a very different way of looking at design.

Eli Russell Linnetz: When you are trying to express yourself, you have to pull from the things you know and use the tools in your tool box. Their background is fashion; they had textiles, stitching, knitting, so those are their tools. For me, even as a photographer, the subject is the tool I have to tell the story. That is why I started to do clothes, because I was so tired of doing these big-budget shoots and people forcing these clothes on me that I hated. I wanted to tell my own story of the world and where I come from, but I hadn’t planned what I wanted to say. I just let that form on its own. My connection to the people is what tells the story.

Andrew Bolton: You started off very unselfconsciously and organically. Now you are successful, do you feel a pressure to overthink things? Is the process less organic now than when you began?

Eli Russell Linnetz: I let that enter my mind for five minutes every few months, and then I remind myself to go back to my bubble and do what I want. People will always want to take and take, so at the end of the day it is about staying true to my process. In my head, I am like, ‘Do I need to reinvent myself every season?’ It’s kind of comforting that some of the most successful people are just obsessed with grey suiting or single silhouettes, and their art is exploring the hell out of that one thing that is locked in their brain.

Andrew Bolton: Your shows have so much creativity. It might be easier to change every season, but if you adopt a position and then constantly refine and dig deeper into it, it is more challenging as a creator. The rewards will be greater, and you will always be associated with it. It’s the same with Chanel: she has remained all this time because she had a singular vision that’s as modern now as it was 90 years ago.

Eli Russell Linnetz: The challenge of working today is that everyone is a curator on Instagram. There are so many people creating every day, which is cool – it’s like a renaissance, everyone can do it – but it really makes you think, ‘What’s my path? My story? What do I really believe in, in the world?’ When you are suddenly faced with dressing people on the red carpet, outside of your little bubble, what does this say? Which is why that A$AP Rocky moment felt so authentic, because I really feel that spoke to a lot of the stuff I do in my everyday work. It wasn’t like, ‘Just make something for this person.’ We are challenged every day to be a new person or reinvent ourselves, and there is an intense bravery in that. I don’t want to compare myself to Rei Kawakubo, but I just admire her work ethic and her practice. Sometimes I feel like, ‘I am going to stick to this one thing and if it kills me then that is the sacrifice I will have made to fully explore this thing and to go where no man or woman or mouse has gone before.’ Every day there is a desire to say I am not that person; I can be other things. Then it takes self-restraint to explore this one story. It’s about finding the nuance and little twists. Like wringing out a rag or making bone broth. Like, how do I pull all of this out of this one thing?

‘People talk about dude culture with your work. There’s so much to unpack: the sweat stains, the unwashed masculinity that you seem to fetishise.’

Andrew Bolton: I am interested in how you are going to evolve your characters. I love archetypes – I know they are dangerous but I love them – because they never age, and I wonder with your characters, the surfer and the jock, how are they going to evolve? To me, they are eternally youthful. How do you see them aging?

Eli Russell Linnetz: I spent years finding these people. You know, I do castings every week, and it is so hard to find the innocence in someone’s eyes and the authenticity that will translate into the photos that once I find someone I feel like I am with them for life. However they evolve, I am going to change with them. I surround myself with so few people and everyone in my life is so important to me that I feel that if I am letting someone into the ERL world, it is because I really believe in them and they really speak to the vision or the story that I am trying to tell. All these people are like my family and they come back every season. In the last collection, The American Tale, the brothers in the suits are from an amazing religious family; they are like surfers from Hawaii. They had such a purity and honesty about them. Hopefully I’ll be able to shoot them again next season. If you enter something with honesty, morality and authenticity, I feel like the people who are supposed to be in your life will come.

Andrew Bolton: This sounds like your own personal manifesto and value system, which you convey through this art form that just happens to be fashion. I think that is what people are seduced by when they see these images. It is more than just the beauty of the image and the flawed perfection of the casting and the sweat-stained body odour of the clothes. It is a realness that comes through so powerfully in your work. The In America exhibition is all about trying to establish a new vocabulary of American fashion based on emotions and the expressive qualities of fashion, and for your particular piece I used the word ‘camaraderie’ because of the stereotypes that you play with. Camaraderie is defined as the ‘spirit of friendly familiarity and goodwill that exists between comrades’. I just wanted to know what you thought about that word and if you would use it to describe that piece.

Eli Russell Linnetz: So many people said they loved how you used that word because it feels so true for that piece. So, thank you. I feel that there is a friendship and a family quality to the characters. If I had to pick a word myself, you know, I would probably say ‘mischievous’. I feel like mischievous is fun, always with a sense of playfulness and humour, even if it can be a little sinister. I don’t like it when things are purely ironic, you know.

Andrew Bolton: ‘Mischievous’ is a good word. As a kid, I loved movies like Animal House, and when I look at your images, I am always reminded of those really fun movies: Cheech & Chong, but with a Sofia Coppola-esque fetishisation of teenage culture.

Eli Russell Linnetz: There was an article that said, ‘Where was ERL when Virgin Suicides was made?’

Andrew Bolton: It’s like Sofia Coppola, Peter Berlin and The Breakfast Club all merged into one thing – the uniqueness of your vision is ultimately what is so compelling.

Eli Russell Linnetz: Thank you. I think it is the connecting of elements on an artistic basis, a collage. It is an irreverent co-bashing of things that just don’t go together in an unforgiving way, yet done with a respect for all these things. It’s post-postmodernism.

Andrew Bolton: I am the biggest fan of post-modernism, eclecticism, historicism and pastiche. There are very few designers who do it well – John Galliano does – but to do it with a sort of aesthetic vision that is completely one’s own, that is post-postmodernism. It’s about gathering all these influences that are personal to you and reconfiguring them into your own singular vision. It is a very rare talent.

Taken from System No. 18 – purchase the full issue here.