Interview by Sara McAlpine

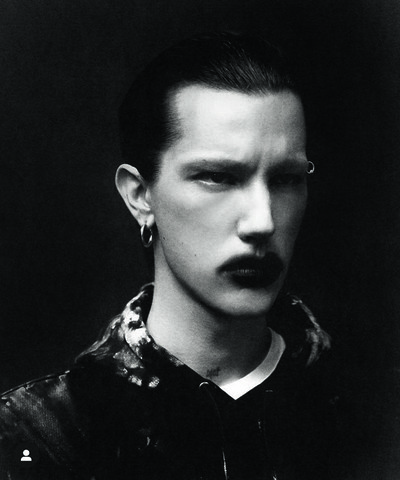

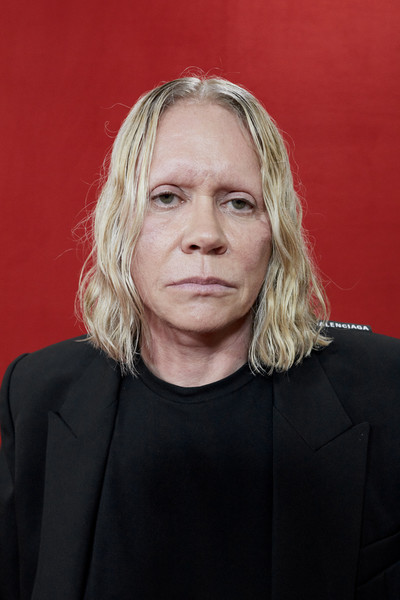

Inge Grognard has been creating visceral beauty looks for the fashion industry’s most boundary-pushing talent for over four decades: the Antwerp Six, Raf Simons, Haider Ackermann, Hood By Air, and more.

It’s Grognard’s relationships with two other figures that mark the most significant chapters in her career, however. The first, with Martin Margiela, launched it; the second, with Demna Gvasalia at Balenciaga, has more recently catapulted her work into the mainstream.

Antwerp is the linchpin that connects the Belgian make-up artist with both, as well as other key collaborators throughout her career. It was where she followed Margiela from their hometown of Genk, in the early 1970s, having become friends as teens. And it’s the epicentre of the creative energy that united her with the Antwerp Six, photographer and husband Ronald Stoops, Raf Simons, and students at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, where she still advises on beauty for graduate shows. It’s also where she first met Gvasalia in 2006, when he was one of those students.

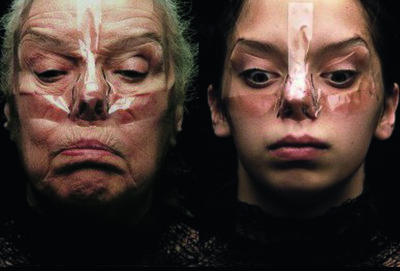

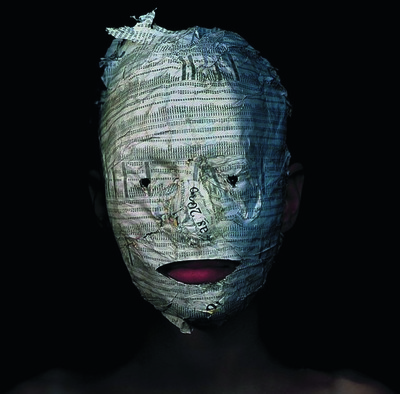

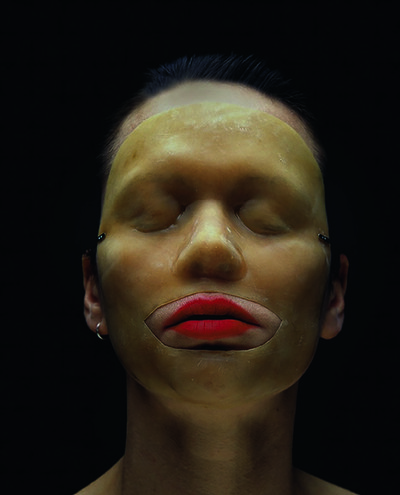

The synergy between Grognard and Gvasalia has fostered innovative future-facing looks, featuring alien, unsettling make-up, and effects that blur the boundaries between what’s real and augmented at Balenciaga: prosthetics made to look like extreme lip and cheek filler at its Spring/Summer 2022 show, and virtual-reality make-up for its Autumn 2021 Afterworld video game.

‘I’m still somebody who very much likes to work with my hands, explaining with my hands, feeling things,’ she says. ‘I have to feel the texture – and it’s the same with clothes.’ It’s a hands-on approach that can be seen in her work with Balenciaga, which fuses rawness and romance to create a dark, subtly subversive glamour, well-matched to Gvasalia’s clothing. Grognard spoke to System about Antwerp, her journey to Balenciaga, and what makes the collaboration with Gvasalia so ground-breaking.

You play a really important part in Balenciaga’s recent history, but let’s start with your relationship with Demna. How did you first meet?

Inge Grognard: I’ve been in the business for a long time. I started in the 1980s, with the Antwerp Six and Martin Margiela, and I later worked with other Belgian designers, Raf and Veronique [Branquinho]. Demna started a whole new era in a way, which is a nice thing. As with all the other designers I’ve worked with, I met them through the Academy in Antwerp. They all studied there, and I’ve been linked to it for a long time, because I consult on the end-of-year shows giving students ideas for the make-up in their shows. That’s how I met Demna. It was such a long time ago that I can’t quite remember our first meeting, but Ronald, my husband, shot his final-year collection. Demna then stayed in Antwerp for a long time, working for Scapa [Sport] with Walter [Van Beirendonck]. What I remember about him, though, is that he was a person who touched me enormously. I remember that he was really human – and for me, that’s so important.

At what point did you actually start working together? Was this prior to Balenciaga?

It would have been when he was at Martin Margiela, after Martin left. I continued for two seasons after Martin left, when the press didn’t know he wasn’t there, and the company wanted to continue working as if nothing was happening. But we didn’t work together properly until he started at Vetements. I got a call from him while he was still working at Louis Vuitton [as senior designer of women’s ready-to-wear], and he said, ‘This is a big secret; I’m starting my own collection. Are you interested in doing the make-up?’ I hadn’t seen anything, but I immediately said yes, and went to Paris. There was no money, but I didn’t care – I don’t care when I believe in people. That was it; I did the first lookbook, then I worked with him again and again, and I’m still going.

Tell me about your early experiences of working together. What was the dynamic between you both and your shared working process?

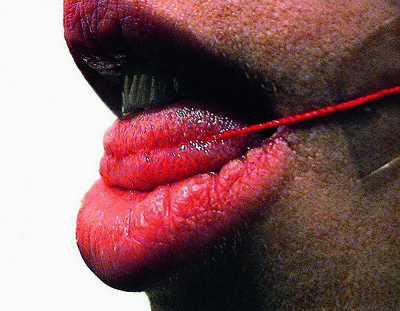

The day of the first Vetements collection, there wasn’t a lot happening: there was a mood board; there was Enya [Vandenhende], who still works with him at Balenciaga; there was a little bit of styling. From that I pick out the things that I wanted to work with in the make-up. The only thing I remember with the first collection we worked on was that we put food colouring on the models’ tongues. That’s why when you see the pictures, the girls are like ‘bleurgh’, with their tongues out. For the rest, there wasn’t a lot of make-up going on, because the clothes were strong, and the models had strong faces. It started with trust: he trusted me; I trusted him and believed in something new. I could never have imagined that he would go onto work for a house as big as this one, but I believed in his work and in him as a person. It’s my first time at such a huge house. I normally work for designers who stay quite small; they stay independent. I never thought things would grow so quickly after Vetements.

‘Coming from a northern country like Belgium, we love a kind of rawness; that is in the work. Also, a lot of romanticism, but with a darkness.’

Has the scale of working for a significantly bigger brand changed the way you work together?

Usually, at a big house, it’s difficult to stay in contact with the designer himself, but the beautiful thing about Demna is that he’s still the same. I still get a brief directly from him, usually very personal, via WhatsApp. He’ll say, ‘This time I’m doing this’, then send me the mood board. I’ll send one back when he wants more of a make-up look; for example, to show what kind of eyeliner look we could do, how I see it.

At what point do you start receiving those WhatsApp messages about the collection and start shaping the beauty look for the show?

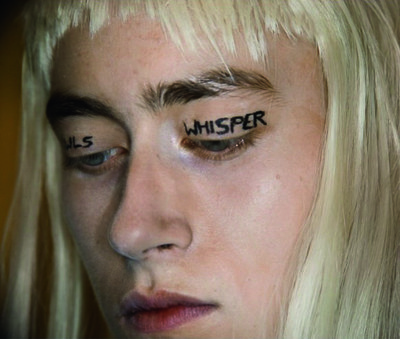

Just a couple of days before. They’ll do a fitting day, and say, maybe, ‘We just want beautiful skin’, and we’ll discuss whether to keep the skin a little shiny or matte – the light at the show is important for me to know – but that’s it. We do change things on the day, though; things that can be done quite quickly, like the eyeliner on the men at the couture show. I initially did it quite straight, but they wanted it to be a little more feminine, so we just changed it. The Afterworld video-game show was quite different, though; it was more precise. Demna had some make-up looks in mind that he wanted to try, so we spent a very long day trying all of them.

Does having only a short period to plan suit your approach? Your work has always felt quite spontaneous with the brush strokes, and where you place

colour.

I always work like that; it’s normal. You get a mood board, specific colours or the music, then arrive the day before and have an hour to propose what you think is the best for that collection. Some designers know exactly what they want, but some are more open. It feels very collaborative at Balenciaga.

How about the advantages of Balenciaga-sized budgets when it comes to creativity, experimentation, and the tools you have at your disposal? You’re now working on make-up for virtual-reality games and digital lookbooks, with special-effects studios to create prosthetics for campaigns and shows.

The prosthetics idea came from Demna. He wanted to work with them, but I specialize in make-up, and that’s special effects, so you need to find the right people to do that. The thing was that it had to look real. Demna wanted people to question what’s real and what’s not; that’s the way he always works. It started with the casting, we took models with high cheekbones and bigger lips. We tried chin prosthetics, but that was a bit much…

How did you respond when he first said he wanted to work with prosthetics?

I’m always open. I knew the difficulty would be matching the colour of the skin to the prosthetics, especially with darker skin. In the beginning, the cheekbones came with blush; the contouring was already there. So we had to work together to make it like any show,where you start with natural skin. The lips looked totally real to me; the models could really have had those lips – because a lot of people do. It was about playing with the idea of what’s real and what’s not, and that’s the bit I really love. That’s why you’ll notice that they all had natural make-up. With Balenciaga, even when there are effects, there is nearly always natural make-up: the base will look like skin because the faces of the models are strong and the collections are strong. When it feels right to have more make-up, there will be more make-up, but otherwise, there is almost nothing.

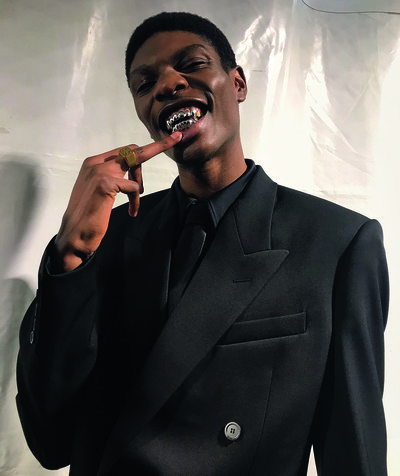

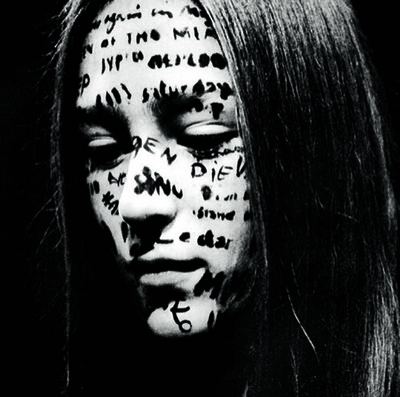

Tell me about the bolder looks you’ve done. Like the big, black ‘bleeding’ eye make-up and red lips for the video game show. Was your approach different because of the virtual reality and gaming context?

Really, no. I didn’t really change anything. It was different only in the way that the models were playing characters, not themselves, and Demna knew exactly which role he wanted the models to play, and which kinds of characters he wanted them to be. It had all the things he loves, too, with heavy metal [references] running through it, with the black eyes, which is something I love in my work, with the running make-up and ‘imperfect’ things.

‘Demna wanted the prosthetics idea to look real, so we took models with high cheekbones and bigger lips. We tried chin prosthetics, but it was a bit much.’

Did knowing that those looks would only be experienced digitally affect your process, in terms of products and technique? Your work has always felt really visceral and tactile.

The process was still me, because in everything I do, even when the look is really specific to the collection or designer, I want to feel my hand in it; the person in front of me is very important. I want to feel the skin, the texture; I want to feel an emotion – and I want to express that. It’s not always possible, but I always try to do that. You can see that more easily in editorial work for magazines, like Beauty Papers, than with brands.

How do you technically translate that feeling into practice?

You need to have the technical skills, which I learned a long time ago – how to make a ‘perfect’ lip or liner, all those things – but, for me, that is not the interesting part. I always want to put my own stamp on everything, to play with it. I’ve always experimented on myself and I’ll always have somebody who has my back, like my husband, Ronald, who gives me really good criticism, too. He’ll tell me, ‘Oh no, this is not working on camera’, which helps me develop ideas.

What feeds your creativity and ideas?

Most of the time, my mood. Anger gives me a big push – when I feel something has happened in my life or in the world that I really don’t like. It pushes me in a direction to say, ‘OK, let’s do something about this.’ Let me do something with that feeling. Ugliness gives me a push; it’s not just about beauty.

What attracted you to beauty as a career or sparked your interest in make-up?

I was interested in clothes; no, I was obsessed with clothes, and I was very particular about what I wanted. Basically, I was difficult! I met Josiane, Martin Margiela’s niece, in high school and met him through her, and that was our thing; together, the three of us were obsessed with clothes. Then, of course, when you think about clothes, and dressing up, you think about the face and start experimenting on yourself – just a little bit of lipstick, a little bit of colour here, thinking about it with the boots you’re wearing, how it all works together. There was lots of experimenting, because there weren’t a lot of magazines I could buy when I was 14. There were Belgian magazines you could buy, all about music, and maybe the beginning of the British magazines – The Face, i-D, Blitz – but we were mostly having fun by experimenting on ourselves. That was our thing.

Tell me more about you and Martin Margiela. Your working relationship lasted right up until he left his brand in 2009 and he was your introduction to the Antwerp Six.

When Martin decided to go to the Academy when he was 18, Josiane and I looked into schools in Antwerp to study make-up. That’s how we ended up there, and we ended up going to the parties with students from the Academy: Walter [Van Beirendonck], who was in Martin’s year, then the following year, Marina Yee and everyone else. We would be around in the evenings when they were sticking things together, working on the collections – just having a lot of fun dressing-up. We would go out, go to second-hand shops and to Cinderella, this basement punk club, where everybody was spilling beer on the ground, smoking cigarettes, with heavy black make-up on their eyes, running around and running out. There was energy.

How did all of that turn into a working relationship?

In a way, I was so lucky to be right there, at the right time, at the right moment, with the right people. You don’t think about it when you’re in it. You don’t ask yourself questions – you just go on, you learn, you make mistakes. That’s how it happens. After a certain time, I was asked by the Six to go to London; then I went to Florence with them in a mobile home. I was just always there, in the middle of a thing that was starting, without knowing it would be a thing that people would still be talking about. There was no ‘fashion scene’ in Belgium. Everything was happening in Paris and London; there was nothing in Belgium.

‘We put food colouring on the models’ tongues. That’s why when you see the pictures, the girls are like ‘bleurgh’, with their tongues out.’

Looking at what was happening in those other cities at that time, though – your first show with Martin Margiela in Paris in 1989 was exactly why he and the Antwerp Six stood out. It was different.

Because we wanted to do the opposite. The other designers in Paris at the time, Montana and Mugler, were all about glamour, glamour, glamour – big liner and false lashes. There was also Yohji [Yamamoto] and Rei [Kawakubo], who were incredible and different from the rest, but we didn’t want to copy them. We wanted to bring something else in make-up and clothes. Coming from a northern country as well, we love a kind of rawness, and there was that in the work. Also, a lot of romanticism, but with a darkness.

What was the response to what you were doing as a make-up artist? You’ve described that first Margiela as ‘chaos’ and said the make-up wasn’t doing anything you wanted it to.

Oh, the ‘chaos’ that first time with Martin, in 1989! Jenny [Meirens], his right hand, had to go searching for assistants for me, because I had no agent. And it was at Café de la Gare, and it was so dark. I had make-up artists everywhere, and we were working with a black pigment that no one was used to working with; I could work with it, but I couldn’t do all the models. It was really black, and you would put it on the eyes, and it would go all over the skin, and we had to clean it the whole time, then as soon as you touched it, you would leave a big black stripe. I was supposed to be in the show – my clothes were hanging in front of me – but I didn’t have time. Impossible! It was so complicated, because the space was tiny, the assistants and I weren’t used to working with each other either, and they were used to working in a way that was very classic. The [critics] were saying, ‘This is not what I want to see now.’ In a way, of course you’re [negatively] touched by that, but I felt that people would understand at some point. They did – but it took a long time.

Let’s talk about the show you just did: Balenciaga Spring/Summer 2022 at the Théâtre du Châtelet, with the celebrities and models on the red carpet, rather than the runway. Celebrities play a huge role in the shows and campaigns at major brands. Do you do that type of work?

You can see on my website – there’s nothing on there about celebrities! [Laughs] There are more and more personalities [involved], but I’ve skipped that for a large part of my life. I’m not always the right person to work with them, because they are very specific about what they want. For the last show, I only did the models. The celebrities – and the Simpsons – were a surprise!

A lot of make-up artists are in the beauty game now, launching their own make-up brands. Is that something you’ve ever considered?

No. Because there are so many brands! The Chinese market, the Korean market, the American market – they’re so huge, what could I bring to it? I wouldn’t know. Also, is there a need for new products? It’s difficult. A long time ago, there were a lot of gaps in the market, but not any more. You can find all the colours you want; you can buy all the basic ingredients from specialist shops in Paris and mix them to make your own lipsticks or whatever, and do your own experiments. It’s incredible. Is beauty still missing something? No. The people who start their own brands are very brave, and they make really nice products. Fenty is really nice, I have them; I have Westman Atelier and Pat McGrath products at home, and the packaging and quality is really nice. You can’t use them professionally, though – the packaging is too heavy! It’s beautiful for the bathroom, but you can’t travel with it. I have a room filled with bags, just plastic bags filled with glitters and body paints and other things.

Do you work with brands to develop your own formulas behind the scenes for professional use? Brands like MAC, with whom you’ve worked since the start of your career.

MAC was the first to sponsor me. They believed in me, and always worked with me on shows. Developing products? Not quite. I would tell them if something were missing, like specific colours. There was this very particular blue, like a BIC pen, that I wanted and I couldn’t find, so they developed it for me. Also, in the beginning, with the lip gloss, I said we need something thicker – and I wasn’t the only one! – so they came out with the Lipglass. So, make-up artists ask for things, and maybe a year later they appear.

What do you think is the future of the beauty industry?

I don’t think something like prosthetics will ever be an option because it’s very complicated to put on the skin. Even applying the products is just too difficult. But plastic surgery has become so huge. When you look around, almost everybody seems to have had something done!