For Omoyemi Akerele, founder of Lagos Fashion and Design Week, the future of the region lies in making the global local.

By Rana Toofanian

Portrait by Akinola Davies Jr.

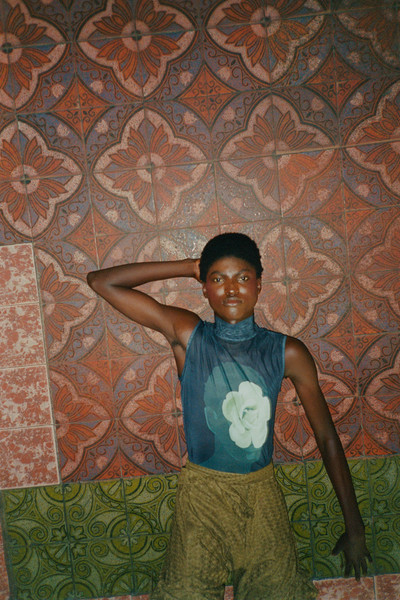

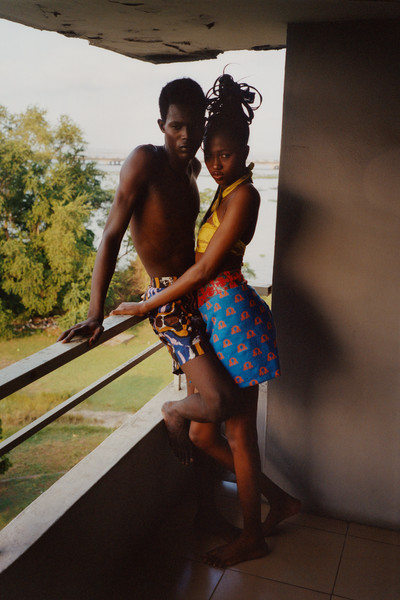

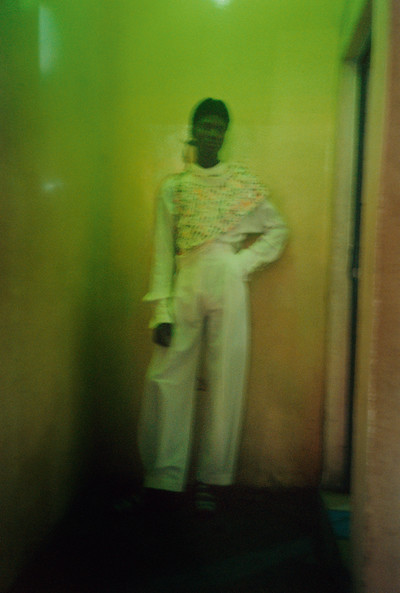

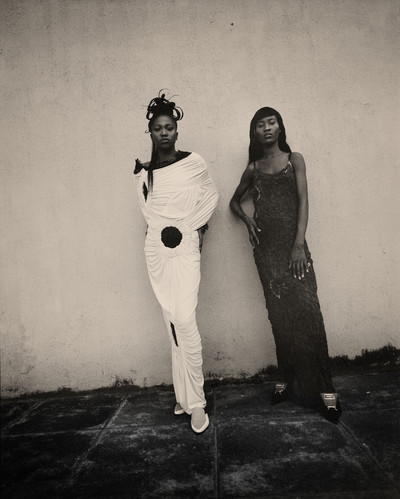

Photographs by Joshua Woods

Styling by Ola Ebiti

Casting by Jonathan Johnson

For Omoyemi Akerele, founder of Lagos Fashion and Design Week, the future of the region lies in making the global local.

‘You don’t just get up and start a fashion week,’ says Omoyemi Akerele. Yet in 2011, that’s exactly what she did, founding Lagos Fashion and Design Week with the aim of developing and giving a platform to Nigerian talent. 10 years on, Akerele is described as one of the most important catalysts behind Nigeria’s flourishing fashion scene. Through Lagos Fashion and Design Week, her talent-scouting platform Fashion Focus, and her fashion-business development agency Style House Files, Akerele has showcased the work of rising design stars, including Orange Culture and Kenneth Ize, and provided business mentoring and creative workshops to countless more.

The Covid pandemic has demonstrated just how close economies can get to falling apart, and the fashion industry, which continues to be overly reliant on imported goods and overseas markets, is no exception. Today, the next generation of Nigerian creatives are faced with bleak prospects, worsened by impending economic crises. Akerele is determined to lessen their burden by rewiring Nigeria’s fashion system to help fresh talent. It’s a mindset she hopes will spread outside her home country and make space for a new era of seamless pan-African cultural exchange.

Following the latest Lagos Fashion Week in November 2021, System spoke to Akerele about the current state of Nigerian fashion and what the next decade could hold in store.

Mohammed wears shorts by Orange Culture, Rhenny wears top by Feben and skirt by Lisa Folawiyo Studio

You worked as a lawyer before founding Lagos Fashion Week and Style House Files. How did you move from law to a career in fashion?

Omoyemi Akerele: This is a story I never get tired of sharing because when I think of how I started and where we are today, I didn’t see it coming. When I decided to walk out of my job as a lawyer in 2004, the reason was purely that I was not enjoying what I was doing. I worked around people who seemed to be enjoying their jobs and I wanted something that would give me a sense of belonging. It didn’t start with fashion, but rather with corporate consulting work and personal branding. Fashion crept in. Then, when I started working in a fashion magazine, I realised that there was a gaping hole between the designers who imagine the clothes and the artisans who work tirelessly behind the scenes to co-create them with the designers: the Afro manufacturers and even sewing machinists in ateliers and workshops across the continent who stitch these things together and bring them to life, and the communities where we source the materials. It was important to step back and see how we could bring all of that together in a way that ensured everyone benefitted.

Growing up in Lagos, what was your interest in and exposure to fashion?

Omoyemi Akerele: I was born and bred in Lagos in a family of seven children, with my mum and dad. My first exposure to fashion was probably the way that my mum dressed us up. It was very feminine; we wore dresses a lot. Fast-forward to pre-teen and teenage years when my friends were wearing jeans, cool T-shirts and leggings, and I was still wearing a frock. I was like, ‘I want jeans and a T-shirt!’ My mum was in shock, like, ‘Do you know how much this dress cost?’ Realising that I was really not that feminine a dresser was my first ‘aha moment’.

I had always been particular about what I wear and how I wear it, but not enough to turn it into a career. At one point I had a girlfriend who was running a brand and had to relocate outside Nigeria. She asked me if I wanted to buy her business and factory. I was still certain that I was meant to study law and so I told her, ‘No, I have no interest.’ I had just got married and I was pregnant with our first child, and that gave me time to do a lot of soul searching. I realised that fashion had always been there in my subconscious. My husband and I had also begun conversations with companies like Mango about bringing the franchise to Nigeria.

What was the result of those talks?

Omoyemi Akerele: We’d also been in discussions with other companies, like United Colors of Benetton, but I was obsessed with Mango at the time and we both thought bringing it to Nigeria would be a really good idea. So, we went to Spain and had the meetings. Thankfully we had done a lot of groundwork and due diligence and listened to the advice we had been given because only six months later government import policies and regulations changed. If we’d invested at that time we would have lost everything. That was the turning point, when I said, ‘I am not going to waste my time or energy to build a brand for someone based outside of Nigeria.’

Rhenny wears a dress by Marco and lace top by Lagos Space Programme, Anthonia wears blue-dye dress by Lagos Space Programme

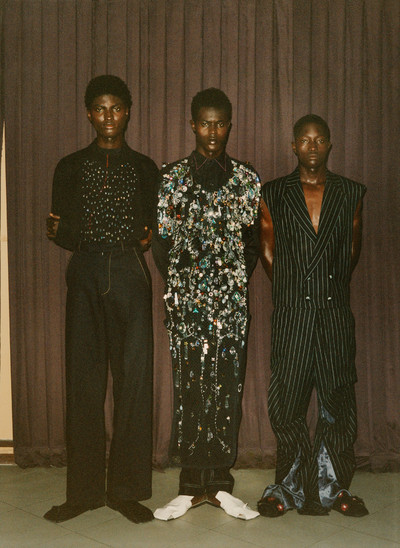

Ebuka wears vest, black shirt and trousers by TJWHO, Mohammed wears dress by Elfrida and shirt and trousers by TJWHO, Peter wears waistcoat and trousers by Eilis Kennedy. All are wearing shoes by Maxivive

You went on to work as a fashion stylist and editor at True Love around 2005?

Omoyemi Akerele: Yes, and I also launched a company with my partner at the time, Bola Balogun, under the name Exclusive Styling, where we worked on some really exciting projects. We styled the presenters, contenders, and music artists featured on TV shows like Big Brother and Idols West Africa, as well as shows that had just been launched in Nigeria like Deal or No Deal. For a while I worked with companies giving talks on the importance of making a good first impression, until I was offered a job at True Love magazine as a stylist assistant. I had to work my way to the top, but less than a year later, I was appointed the magazine’s fashion editor. It was during that time that I understood that disconnect between the designers and those sourcing the fabrics, as well as the between the supply chain and retail. I realised I was interested not just in the public-facing image and design side of things, but also in what happens when clothes are produced. How do you sell them, market them, and wear them?

What was the fashion landscape like in Nigeria at that time?

Omoyemi Akerele: Nigeria had gone through a phase where the influx of imports from China and elsewhere had led to a decline in Nigerians wearing Nigerian clothes. As a result, local industry and textile manufacturers had suffered, which meant the whole value chain suffered. [Manufacturing] was the second biggest employer in Nigeria in the 1980s, but there was this gradual decline until only 13 or 14 textile factories remained in operation. So I was curious to find out how I could contribute beyond just making editorials and shooting their collections. Styling and consulting are great, but I’d realised there was this gap and that someone needed to fill it. That was something I had to debate: what can I do here? Why a fashion week? For me, it was meant to provide proof of concept.

‘Nigeria had gone through a phase where the infux of imports from China and elsewhere had led to a decline in Nigerians wearing Nigerian clothes.’

You wanted to create something inherently Nigerian. What is the DNA of Nigerian fashion? How does it differ from New York or Parisian fashion?

Omoyemi Akerele: When we started out, we decided to focus on what is happening in Nigeria. I knew that we had the talent here, and I thought we could bring people together and offer them a platform to show their work. Then through that we could train people and provide opportunities. We’ve never been able to do that on the scale we wanted, but it has still impacted on some of the brands we work with. Beyond that, a fashion week means bringing all those things together as a way to experience fashion from the whole continent, not just from Nigeria. To experience fashion is to experience culture. It means coming to Lagos and feeling the city’s confidence; its energy cannot be rivalled. The collections we show tell a story of how diverse and dynamic our culture is. They speak to historical references, resilience and grit. All the obstacles designers face daily, but they are still able to create, celebrate, and express who they are through their collections, season in, season out. It is about creativity and innovation, but it’s also about creating jobs through collaboration.

How would you describe the fashion scene and manufacturing landscape in Nigeria and more broadly, in West Africa right now, particularly with Covid?

Omoyemi Akerele: At Style House Files and Lagos Fashion Week, we have tried to reinforce some of the things we believe in, like co-creation and collaboration within our community. During the pandemic, for example, we brought people together to come up with creative solutions, from sourcing and producing PPE to supporting the government’s attempts to reduce the spread of Covid. It was groundbreaking for us to see people in this fragmented ecosystem working together. Our community has been strengthened because we’ve realised that we can do more together. People have relied on each other for support and for encouragement. So while the biggest challenges we face as a fashion community are around sourcing, due to our long-standing dependence on imported raw materials, what has come out of the pandemic is that designers have joined with the wider community to build more integrated businesses. It reduces our carbon footprint and waste in a way that only sourcing locally and on demand can do. It has empowered craftsmen and local supply chains, and generated more income for our people and economy, in the midst of inflation.

There is a huge market for secondhand clothes across Africa, specifically in West Africa and in Nigeria. What are some of the problems with this retail ecosystem? How are new designers impacted if these shipping containers of clothes keep arriving?

Omoyemi Akerele: People often think they’re doing something laudable by sending all the clothes they no longer wear over to Africa where people need them. Yet there is a more fundamental problem: companies and brands all over the world are overproducing and people are consuming and buying more than they need. The problem is this culture of waste. It is important to establish that. Africa is not the solution to the global waste problem or the overproduction and overconsumption of goods in the West.

Closer to home, the problem is affecting the local textile industry. The creation of this secondhand market, which can serve a large part of the population, is discouraging local production that could create jobs for Nigerians. Local production also means you can trace garments from sourcing to the final product in a way that benefits the economy, rather than these containers coming from Britain and elsewhere. Half of the contents are destroyed by the time they get here anyway. The solution is more about not creating waste in the first place.

Two of your initial intentions in starting Style House Files and Lagos Fashion Week were to help centralise and structure the local fashion system, and put Nigeria and Lagos on the map. After almost a decade, do you think you have met these goals?

Omoyemi Akerele: We started out by putting Lagos on the fashion map and showing that it is possible to open the gates of business in Africa. There is talent, and beyond talent, there is a market, and beyond a market, there are people who have succeeded in running [a successful fashion business]. Within the first few years, I think we succeeded in doing that. Now, the bulk of our work is in building longevity and a structure that creates solid businesses. We have our work cut out for us and we’re not at a point where we can give ourselves a pat on the back. However, we are on the right track. At first, we were strictly focused on providing a platform for designers to present their collections each year, but as we got more involved, we realised that we needed to do more skills-building and development. Beyond presenting their collections, we wanted to make sure designers could manufacture their garments locally or on the continent. We have since ensured meaningful conversations between the private and public sector and are exploring ways of solving the industry’s infrastructural challenges. So much more needs to be done.

Some of these challenges are not particular to Nigeria, but they can sometimes incapacitate creatives and make them want to give up and just stop; some already have. We also realise that this happens in other fashion cities around the world. Challenges exist, so how do we work around them? That’s why we believe that our collective task is to create a lasting structure that adds value to this creativity. These designers must be able to build businesses that can survive changes in the climate, to create communities of artisans who also benefit from them. What is really dear to my heart is how we equip our youth with skills and opportunities. It’s the most important factor of all in a country with such high levels of youth unemployment.

You talk about the advancement of Nigerian fashion in the larger context of the African and West African apparel and fashion industry. How important is it to see the bigger pan-African picture?

Omoyemi Akerele: Countries working together across the continent is the future. It’s vital that we create room for knowledge exchange and transfer. I see the future as a Nigerian designer who opts to work with a community of artisans in Nairobi or Burkina Faso. So it’s important we have a holistic approach because as the movement of people across the continent has increased, so has our footprint across other countries within Africa. The question becomes: how can we benefit from the African Continental Free Trade Area, which has just been implemented and means the movement of goods across the continent is being simplified?

‘Beyond presenting their collections, we wanted to make sure designers can manufacture their garments locally or on the continent.’

How do you select designers for Lagos Fashion Week and how is new talent discovered and fostered?

Omoyemi Akerele: We are a small platform, so there is a natural limit to the number of designers we can present each year. This means the selection system is based not only on who is out there, but also what they are doing: how many collections can they produce a year? Where do they sell them? What is their design aesthetic? It’s not just about talent, which is great; designers have to understand that if we give them this opportunity, they have to run with it. That is the criterion. The internal committee goes through lookbooks, websites or even just an Instagram page to decide. If you show with us, you are automatically invited to the next season if the brand has seen sufficient traction during the intervening year. It can’t just be a hobby. That’s sometimes been a bit restrictive because you can’t keep bringing in new people. So, we have a platform for the young designers, which was once called Young Designer of the Year, but has since morphed into Fashion Focus. It has been our dedicated channel for introducing new talent to Lagos Fashion Week each year. We’ve showcased brands like Orange Culture, Lagos Space Programme, This Is Us, Kenneth Ize, and Cynthia Abila, and it’s become an incubator over the last three or four years beyond just scouting for new talent.

We’ve realised that we can only foster new talent by collaborating with different organisations, such as the British Fashion Council. We’ve also worked with established designers in the industry who offer classes to encourage young designers. And we’ve worked on offering more one-to-one support. For example, our in-house team runs sessions and goes through different topics where people can get a deeper sense of the everyday aspects of running a fashion business. It’s about offering that extra layer of support that young brands don’t always have access to. There also has to be self-investment. We need to realise that African fashion has something tangible to offer the world, and that we need to work to bring it together, to bring it to life. It is important that, even though we might have our differences, we have to build these structures ourselves because I don’t know that we’ll ever get there if we keep waiting for a messiah to come and save us. So the building has to be done by ourselves, by our stakeholders, by our governments, our people. We have to build lasting structures to strengthen an ecosystem in which everyone matters.

Has there been sustained and meaningful interest in Lagos Fashion Week and its designers from the global fashion media and press ?

Omoyemi Akerele: There is only so much the press can do. There are people who get on planes and come to Nigeria with their saviour complexes: ‘We are going to save African fashion!’ They get paid quite a lot and then go back to their lives. My question is, while they are away from Nigeria, what should the members of the local fashion community be doing? I say that they should focus on their businesses, selling wherever they sell, because sitting around waiting for hype can be a ride to nowhere. We are always mindful of telling people to straddle both worlds: absorb the attention when the press is here, but know where your market is.

Also, the press works better if the brands are actually in the stores because consumers at least have access to the products. We are about to launch a collaboration with Moda Operandi, and we’ve put designers in Selfridges, MatchesFashion, and so much more. But designers also need funding to be able to produce their work in commercial quantities so that the conversations about them in the press do more than just feed the hype. The most important thing is for the world to realise that African creators and African culture are not trends; it is who we are around the clock. We need to move beyond these narratives. Only then will it be easier for us to get round to the business of fashion. Otherwise we are just exposing the brands to be copied and exploited commercially.

What do you think the next decade looks like?

Omoyemi Akerele: The mood is one of cautious optimism. I want to hold onto this because I am an incurable optimist – I am a hope dealer. We are operating in a weakened economy post-Covid, a lot of small businesses are on the verge of collapse. There is no sign of stability – economically, politically or even across our health sectors – so I believe the next decade lies in our collective mindfulness. To be able to co-create solutions to strengthen our existing ecosystem and ensure that creatives bene”t from their work in a way that reverberates across the value chain. I believe that this could be a key strategy for equipping our brands, our creators and our designers with the tools that they need to survive the next decade.

You’ve said in the past that fashion saves lives. What did you mean?

Omoyemi Akerele: One reason I do what I do is that giving up now is not an option; it is too late. We have rallied together with the support of these teams and a community that believes in us year in and year out. They have given their time and commitment to working on and showcasing the platform. We are all part of this community that really believes that creative and cultural industries can contribute to the economy and create jobs. In that sense, fashion can save lives. Our reason is to be able to create lasting opportunities that outlive us all, so that the next generation and the generation after them can also benefit from it. We do it because we have to.

Taken from System No. 18 – purchase the full issue here.

Models: Anthonia at the Claw Models, Precious Peter at Sage Models, Rhenny at 90s Models, Mohammed at the Claw Models, Ebuka at Cias Models, Peter at Ethos Models.

Make-up: Lauretta Orji.

Hair: Kehinde Are.

Casting: Jonathan Johnson.

Styling assistant: Laura Osare.

Make-up assistant: Ifeoma Kalu.

Hair assistant: Adebisi Sherifat.

Production: Generation X. Producer: Gina Amama.

Assistant producer: Ayeblue Gbenga.