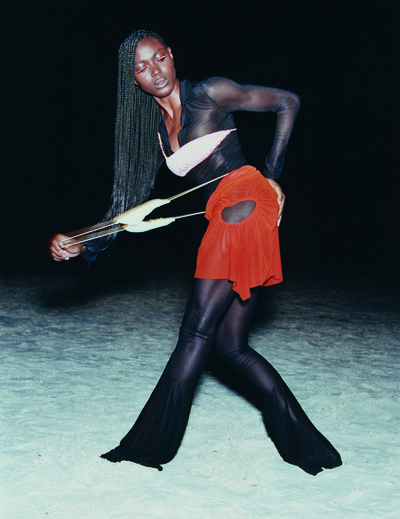

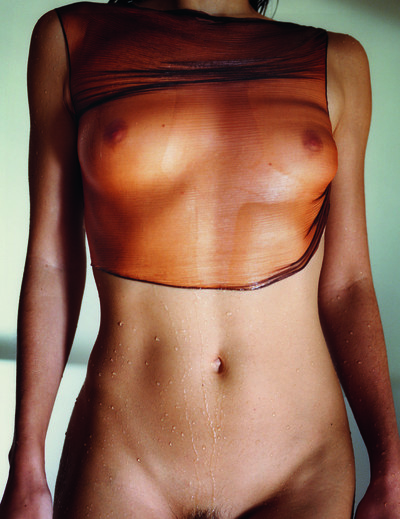

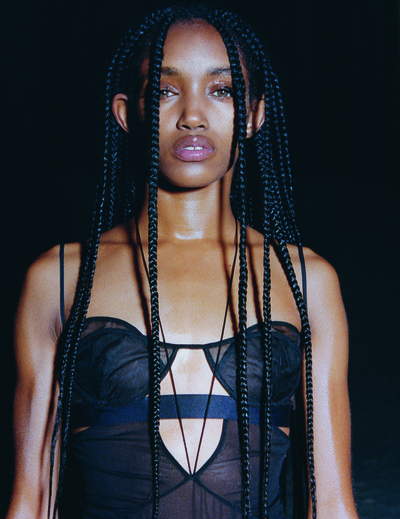

Supriya Lele, KNWLS and Nensi Dojaka, on London’s new wave of womenswear, designed by women for women.

By Vanessa Ohaha

Photographs by Drew Vickers

Styling by Vanessa Reid

Supriya Lele, KNWLS and Nensi Dojaka, on London’s new wave of womenswear, designed by women for women.

Despite Brexit and Covid-19 with its many lockdowns, London’s fashion infrastructure has remained intact. With its renowned fashion schools and organizations such as Fashion East and the British Fashion Council, the city is still the place that recognizes perhaps better than any other the value (financial or otherwise) of nurturing young designers and their talent. Out of this changed but still vibrant scene have emerged three labels, Supriya Lele, KNWLS and Nensi Dojaka. Designed by women for women and already being worn by Rihanna, Dua Lipa and Bella Hadid, their clothing shares an appreciation of the female form, telling nuanced and delicate stories from a female viewpoint.

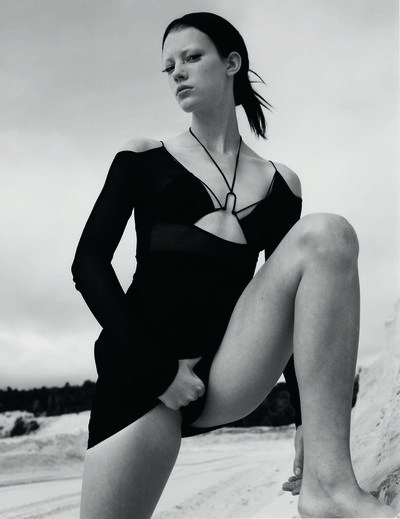

British-Indian designer Supriya Lele’s eponymous label, founded in 2016, is deeply rooted in her own cross-cultural point of view, examining her Indian heritage and British cultural identity through drapery and twisted sheer dresses. Lele’s first standalone show, a highlight of London Fashion Week in 2019, led to her selection as a finalist for the LVMH Prize 2020.

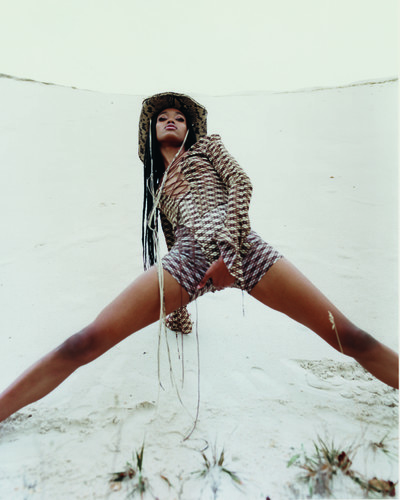

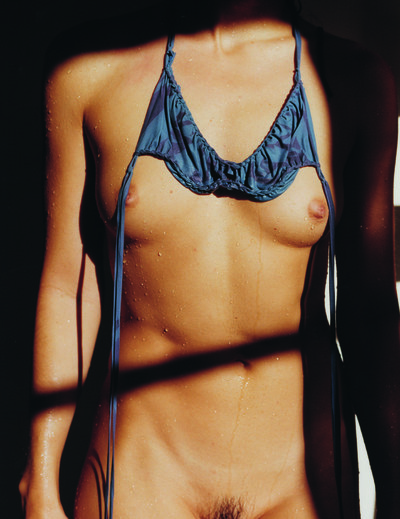

Since her debut collection for Spring/Summer 2018, Charlotte Knowles has established a reputation for clothing that is a rich celebration of women’s sexuality. KNWLS, the South London-based label she founded with design partner Alexandre Arsenault, uses a corsetry and underwear-influenced aesthetic to deconstruct ideas of what ‘sexy’ can mean.

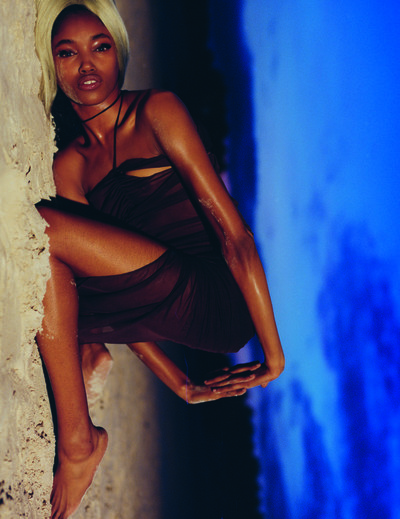

Winner of the 2021 LVMH Prize and already a celebrity favourite, Albanian designer Nensi Dojaka creates lingerie-inspired dresses and cut-out pieces that play with 1990s aesthetics, sheer fabrics and layering to express a vision of modern femininity that embraces both vulnerability and strength.

System met the designers to discuss their work and influences, the importance of creating for women, and their dreams for the future of British fashion.

Supriya Lele

How important a role does your cultural background play when you’re designing a collection?

Supriya Lele: The core of my brand is an exploration of my identity and my heritage. Having been born and brought up in the UK but being of Indian heritage, there is a tension and balance between the two cultures that I find a continuous source of inspiration and identity. It continues to evolve, as I unpack more about myself as the years go on and so I don’t think it’s something I will ever not explore in terms of my work. Having these conversations about identity through clothing is important.

Your clothes show an evident love and respect for the female form. What do you think of the word ‘sexy’ in relation to your work?

I don’t necessarily have an issue with the word, but what does it mean? Through whose lens are we seeing something as sexy? My work is a reinterpretation of what I grew up seeing: going to India and being exposed to the culture through the female lens, my family wearing these semi-sheer saris and having varying degrees of skin showing. I always felt like it was a love letter to the female form. It conceals and reveals; it’s attractive; it’s sensual; it’s respectful. The word ‘sexy’ just doesn’t mean anything to me. My work is evocative, powerful, daring, and the word ‘sexy’ reduces it down to imagery I don’t identify with.

How has your work evolved since you first began?

At the beginning, I was really trying to put myself out there. I was doing work that I felt I hadn’t seen before and many aspects of it were quite new to other people. The first few seasons, I was trying to find my feet and what I was trying to say as a designer, while building a solid fan base. Now it’s really more about reconsolidating my vision. I have built quite a large personal client base, so alongside my wholesale clients, there are interesting women purchasing the clothes. That helps me ground the work and redirect it. It’s really about re-establishing the woman each season.

Who is the Supriya Lele woman?

When I first started out, I used to think that this was an exploration of myself. Now I have this extensive client list, I can see who my women are: from art curators like Antonia Marsh to designers like Gaia Repossi, to stylists and lots of female artists. It’s exciting to have a connection with a super talented artist, but, you know, my mum wears my pieces, too. They just need to have an amazing connection with the clothes. Oh, Rihanna likes the clothes! She is the woman of the world; she’s not afraid to be herself.

What were the biggest inspirations, that made you want to be a designer?

A big, melting pot of things. My parents were just really into clothes. We’d find ourselves talking about clothes. I grew up in the 1990s and we’d watch [weekly TV music show] Top of the Pops with my mum and my friends, just to see what was hot in pop culture. I was also really into music, so I would go to concerts and was part of a lot of subcultures. It was pre-Internet and so I really immersed myself in the culture of things I was interested in, being a bit of a nerd, learning about the things I liked.

Is there a particular subcultural period that influences your design philosophy?

Like most teenagers, I had a phase where I was very into being goth. But it wasn’t exactly about that specifically for me, it was about the ‘anti’ ethos. The 1990s designers who really embodied that kind of anti-ness would be Margiela and Helmut Lang. They were really just doing their thing. It was kind of revolutionary and against the grain in some respects. I have nothing but admiration for designers who push against what’s popular. I guess that comes from me feeling like an anomaly. I’m just doing what I want to do.

Why did you focus on the female form and how do you question what femininity means in your design?

I’m a draper; that’s how I work. I learned draping from helping my mother and my granny put their saris on and so it just felt like a natural way for me to work. I don’t think I’m trying to pose a question about femininity. I just want to be able to have roots in India and here in England, then take those references, reduce them to skeletal forms, reinterpret them, and make them into something that feels modern. It’s about these whispers and notions of things, and the feeling it gives, like empowered confidence.

Post-pandemic, what is the current state of London Fashion Week?

I recently went back to catwalk format, but before that we had done a shoot and appointments and a film. I enjoyed each different method. I did a show this season because it felt like the right thing to do. It’s easier now to present in whatever way feels right for you and your brand. That takes a weight off your shoulders; you can just go with the flow. Things are returning, but it still feels tentative in some respects, which is really cool.

Your clothes have been worn by celebrities and stars, so who would you like to see wear them next?

If anyone wears something of mine, then it means I’m doing something right.

KNWLS

How would you describe the KNWLS design philosophy?

Charlotte Knowles: The label has always been about the relationship between intimacy and sensuality, and power and strength. There’s also a connection with the digital age and how ideas of sensuality are presented in the digital world.

Why womenswear?

Charlotte: I identify with it because I am a woman and the way I design is very personal. We’re also interested in a menswear take on womenswear and how garments are finished and tailored. We were also taken by challenging how people see womenswear and putting out garments that are well developed.

What are some of your biggest inspirations?

Charlotte: The people who surround us, watching a movie, chatting with our friends or people we respect. Like Grimes sending us a random manga character that she thinks fits the brand’s aesthetic. All these kinds of things build this world. We grew up in the 1990s and 2000s, so we think about extracting things from those years. There are so many subcultural elements from that era, which we add to that exchange with the people around us, to create this effervescence.

Are there any other subcultural eras that influence your design?

Charlotte: We draw from all eras. Some of the underwear I look at is from the 1800s. It is such an eclectic mix, and the reality is that a lot of these eras are regurgitations of previous ones; it’s all kind of linked together. The 2000s is just because we grew up in that era, so it’s kind of embedded in our psyche.

What do you think about the notion of ‘sexy’ in relation to your designs, and how has that evolved for you?

Charlotte Knowles and Alexandre Arsenault: For us, achieving sexy is like walking a fine line. We like to balance a sense of conceal and reveal, something dangerous with something in control. That can be the way the clothes reveal the body or through the sheerness of the fabric and layering, which then results in something complicated, strong and sharp. We always try to add something dangerous, so that the girl is not just sexy, but also strong and in control. There’s always something slightly unapproachable, like a dangerous creature you have to appreciate from a distance. Even when we make underwear, it’s never worn in the way you’d expect underwear would be worn. It’s the fabrics or the techniques we use, like boning, which are always done in what we like to think is a futuristic manner. It does feel sexy, but for me that’s not the word I would use. What we do is never vulgar; it’s incredibly empowering and fierce.

What advice would you give to an aspiring womenswear designer?

Alexandre: Put the work in, it’s about being driven. Surround yourself with good people, people who care about you as a person.

Charlotte: As a woman in this industry, I have sometimes felt a bit like the underdog. It’s very important to just do what you want to do, especially when it is something that you love. It is very easy to be distracted by other people getting attention, but as long as your work speaks for itself and you exist through your work, you are going to find your own audience.

Which celebrity would you like to see wear your clothes next?

Charlotte: We are quite obsessed with Hunter Schafer and Olivia Wilde; I’ve always wanted her to wear something of ours. We need a Rihanna moment. She has worn some of our stuff, but she’s never been photographed in it; she’s always worn it under a big fur coat. We’d love a Rihanna moment.

Fashion shows were as affected by the pandemic as many other physical events or gatherings. What do you think of the current state of London Fashion Week?

Charlotte and Alexandre: We found it really refreshing to be able to release content where you controlled the final image. It’s so unlike the runway where it’s almost always completely out of your control. It also showed people that it’s possible just to release your images or film and still be successful. Hopefully this period will show young brands that they can still be successful without having to stage a runway show.

Nensi Dojaka

How has your cultural background influenced your design and creative process?

Nensi Dojaka: I was never really inspired by my cultural background, but the way I was brought up had a big impact on the things I’m doing now. I was in drawing classes when I was very young. My parents put a lot of effort into making sure I was trained in the arts even though it wasn’t a thing in Albania, and in many ways still isn’t. I always knew I was going to end up in the arts. That said, I’m not really inspired by the visual aspects of my background, but more by how I was raised.

How important was it that you had supportive parents?

Very important. It’s a bit of a risk when you pursue a career in the arts because the future is never really clear. I also didn’t know how I wanted to continue my career, but my parents believed in me, even when I made the switch from lingerie to womenswear.

A lot of your work shows your lingerie background by being flattering to the female form. What do you think of the word ‘sexy’ to describe the clothes you design?

For a woman to feel sexy she needs to feel powerful and confident in how she looks when she’s wearing the clothes. Sexy and powerful go hand in hand and that’s very important for how women are viewed. The way I do it is by mixing feminine details with more masculine aspects like tailoring and that juxtaposition is very important.

How have ideas of female empowerment appeared in your collections?

When I watch my runway shows, I love the look of a model wearing these strong trousers paired with a sexy bustier or bralet. The image of her walking down looks really strong, kind of aggressive, but still very female. To me, that visual carries the message of an empowered woman.

How has your work evolved since you began?

When I first started, it was more visual, putting things together, but when I went to Saint Martins for the MA programme, it became more about defining the woman I make clothes for. She’s becoming more mature, more self-aware and confident now. That may be a reflection of my getting older as well.

What were your biggest inspirations growing up? What made you want to be a designer?

We didn’t have a lot of cultural events in Albania when I was younger, but my drawing classes were super inspiring. Then when I came to the UK at 16, I went to a Mark Rothko exhibition and all that art stuck in my mind. It confirmed to me that I wanted to work in the arts, and then fashion became my medium.

What subcultural period had a big impact on your design?

Definitely the 1990s. Mainly because designers in the 1990s seem to have done what I want to do. At the time it was a bit more sexualized, while I’m trying to make it a bit more empowering for women. I was also inspired by how clean and minimal a lot of the clothes were back then. When I design, I begin with those small details, and it can initially look a bit messy, but at the end it has to look clean and nicely resolved.

What would you say to an aspiring young female London-based designer?

Persevere and stick to what you believe in, especially when you may not have the same support as your peers. It is important to have trust in yourself until the results start to show, and others start to believe in what you’re doing as well. Carefully analyse why it is that you’re doing what you’re doing so that you can have faith in the choices you are making.

Is a sense of community important for women in fashion?

It is important to have a community, to feel supported by other people in the industry, and to share thoughts. I work with a lot of women. My stylist Francesca Burns is someone who I really respect and my team is filled with women I admire.

What is some of the best advice that you have been given?

At the LVMH Prize, I was told to continue what I was doing without losing sight of it because it can be easy to succumb to commercial pressures. I think that was such good advice.

What celebrity would you like to see wear your clothes next?

I loved seeing Zendaya in my clothes; I love her, so I really enjoyed that moment. Next, maybe someone like Anya Taylor-Joy. I think she’s very intelligent, I love how she’s always talking about books. She’d be great.