Interview by Tim Blanks

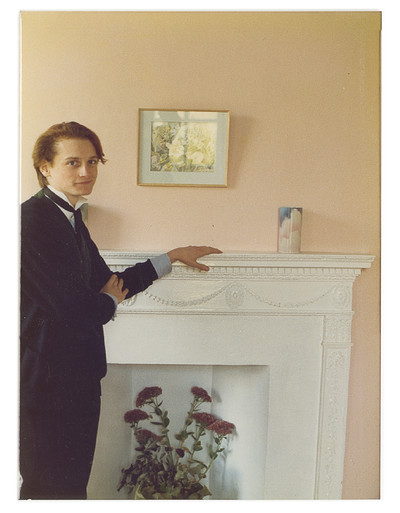

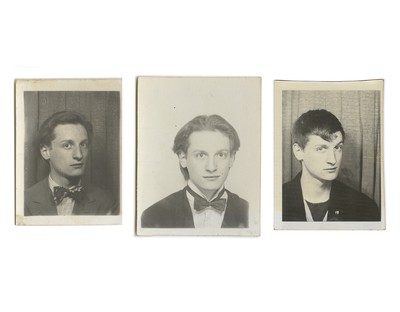

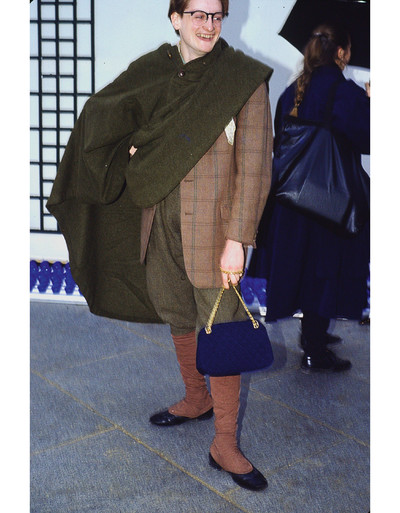

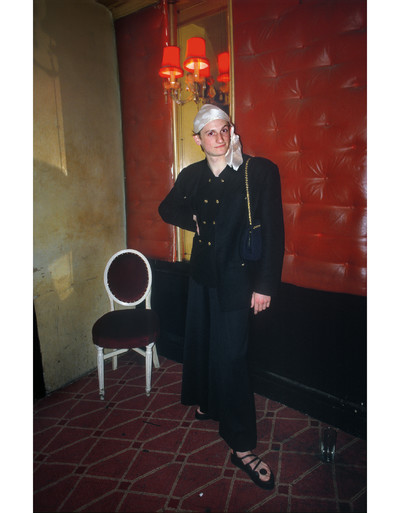

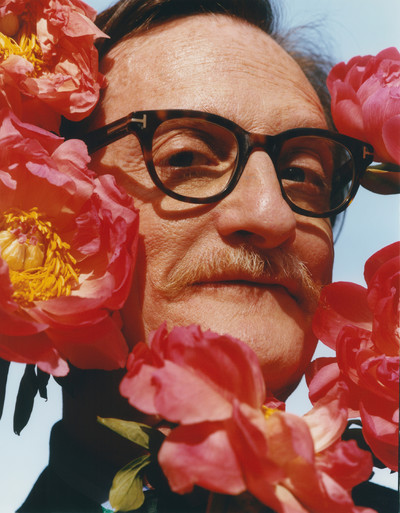

Portraits by Tom Johnson

Immoderate aesthete Hamish Bowles recounts a life oh-so less ordinary – from Beaton to Bowery and back again.

There is something Bergmanesque about the notion of a world of interiors, suggestive of the endlessly unfolding lotus of the human psyche. A magazine that focused on people’s environments and lifestyles might more logically acknowledge exteriors in its title, but one of the enduring attractions of World of Interiors in its four decades of existence has been its weaving together of inside and out. It’s been a celebration of the idiosyncratic – often eccentric – self as expressed through decor, art, architecture, gardens, and accumulations of all kinds. Hamish Bowles arrives as editor-in-chief at the magazine – his first issue was published in March – as a man whose entire life been remarkably steeped in such things. ‘Precocious’ is an inadequate descriptive for a seven-year-old who lambasted Cecil Beaton’s Edwardian fantasia in My Fair Lady for its lack of historical accuracy; I’m more partial to ‘intrepid’. Like an Enid Blyton character, Baby Bowles was fearless in his pursuit of adventure, although the lost treasure he found was more usually in junk shops and jumble sales than pirates’ caves or smugglers’ hideaways. From the outset, he was gifted with an acute awareness that all the objects he collected had a story to tell about the people who had once possessed them. Bowles has made it his life’s work to learn those stories and pass them on. A repository of vast knowledge about the arcane workings of self-expression, he has made himself an exemplar of the very notion, a dandy as definitive in our times as his hero Beaton was in his.

Towards the end of our conversation, Bowles muses that he’s lived his life backwards. Blyton to Beaton to Benjamin Button – a whole world of interiors right there. Exteriors-wise, he’s grown a moustache (‘to try and give myself more authority,’ he claims). We’re in his office at Vogue House in London. He’s still waiting for his smart desk but, enthusiastically deep in a mess of layouts for upcoming issues, he is clearly a man in his element, interior life and exterior world in enviable harmony. Cometh the hour, cometh the man at World of Interiors.

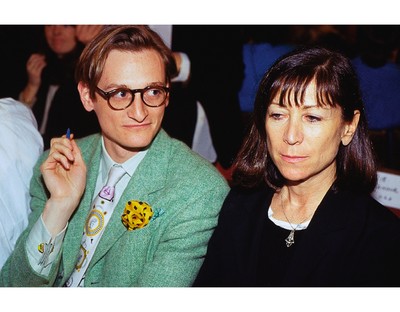

Hamish Bowles: I’ve been styling houses for 30 years for Vogue, and a bit at the end of my Harpers & Queen life. I joined Harpers as a junior fashion editor and then ultimately the fashion style director. It was all fashion shoots, a lot of locations and styling of interiors because there were a lot of narrative stories involved. Then I sort of initiated the idea of photographing women of style in their environments. So we did Madame Lacroix and Bettina Graziani, and Inès de la Fressange, and C.Z. Guest at home in Long Island. That kind of thing. I adored doing that because it was a folding-in of the idea of self-presentation and how you created an environment, and how autobiographical those rooms were. I mean, with all those women, their environments were an extension of how they presented themselves, how they dressed themselves. So that was really fun. And then the strangest thing happened in retrospect: Gabé Doppelt, who had been Anna [Wintour]’s PA when she was at British Vogue, was producing some of the back-of-book stories for American Vogue. She called me up and said, ‘I hear you’ve got a great apartment. Can we do a story?’ That was my first apartment on Westbourne Park Road and Powis Terrace, which was about the size of this office. Patrick Kinmonth interviewed me. I was very pleased, though it was quite a surprise because I was working for Hearst essentially.

Tim Blanks: That was the lavender flat. When you walked past it at night, it was practically glowing. Everyone seemed to know it was where you lived.

Really? How funny. The hilarious thing was after I had just finished it – by which I mean physically painting it myself – I was so proud of the glowing lavender with chartreuse accents, and the electrician came because I wanted to reposition a light switch. He had a magic marker and did a big X on the wall, and he said, ‘Oh god, I bet you’ll be glad when you can get rid of all this crap with a lick of magnolia!’ He was thinking I had inherited some freakish apartment. Anyway, the story ran in the September issue of Vogue, and by that time I was actually working there because I’d got a call in the summer totally out of the blue from Anna. We had open-plan offices at Harpers – it was like a fish tank – and there was this rather crisp voice on the end of the line, saying, ‘Hello, this is Anna.’ I literally turned crimson. She said, ‘I’m just looking at the pictures of your flat in London. It looks very interesting and I can see you’re interested in decorating, so this job has come up and I think you would be perfect for it.’ The style editor Catie Marron was leaving the magazine so she could focus on decorating her own apartment at 714 Park Avenue. It was quite interesting because people wouldn’t have thought of me at that point as being an interiors person, but I was obviously obsessed by them. I’d already been a fashion editor for seven years. I joined Harpers in 1985-1986. They’d offered me a job before I’d finished at Saint Martins…

You did the ‘Teenage’ issue of Harpers & Queen, didn’t you?

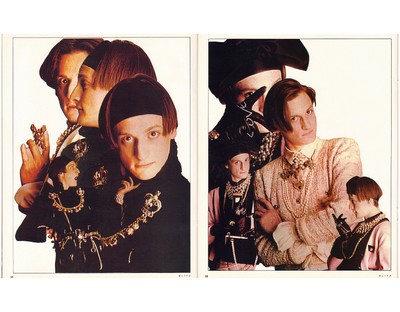

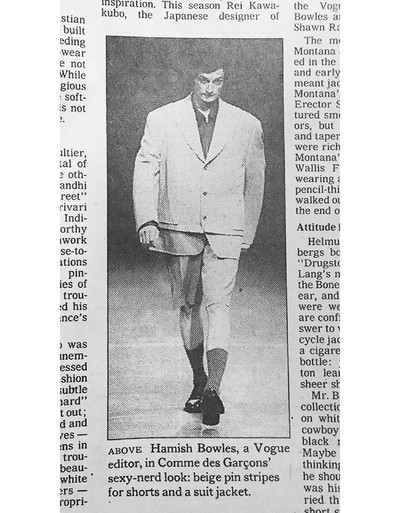

That issue [August 1983] was my first introduction. I was doing my foundation course at Saint Martins and Harpers & Queen. I’d heard about the issue and I went in to see Vanessa de Lisle and Elizabeth Walker and they assigned me the menswear pages. I worked with Mario [Testino] for the first time and we did a story at the Royal Academy, which I called ‘Walk on the Wilde Side’ and was altogether not appropriate for a teenage issue. It was quite fun. It was my first ever cover line: ‘and Hamish Bowles shortens the trouser.’ Everything was above the ankle. Take that, Thom Browne! Anyway, it went down very well. Then they didn’t really like the slightly earnest, Edwardian, uniform-y schoolgirl story that the women’s fashion editor had done so they asked me to do a womenswear story as well. So I thought I would do The Women and I went to Stephen Jones on Lexington Street. That was probably the first time we met. He’d done all these divine little hats with spotted-chenille veils; they couldn’t have been more Adrian. Antony Price had done all these broad-shouldered suits. So I did this whole thing, and then Vanessa de Lisle appeared halfway through the shoot and said, ‘Oh, this looks old, old, old and I want young, young, young!’. We ended up with poor Annabel Schofield with this backcombed hair, literally looking like she had put her fingers in an electric socket. I had to bite the bullet. In fact, very funnily I was just reminded of it because I recently found the original Polaroids for that shoot.

‘My father would be driving us along and if we saw a junk shop my mother and I would jump out and rush inside, while he’d wait in the car, absolutely furious.’

You were doing The Women for the teenage issue?

Yep. Vanessa de Lisle, in retrospect, politely said, ‘It didn’t smell like teen spirit.’ She was thinking of nice ‘hooray’ girls at… oh my god, what were those Chelsea clubs those girls used to go to? Anyway, that sort of vibe. They asked me back to do freelance things after that and I was also doing things for The Face and some of Franca [Sozzani]’s magazines in Italy, even though I was still at Saint Martins. Then, in my work-experience year, that sort of amped up, and I was doing things for Harpers. John Galliano had just graduated and he and Amanda Harlech – Grieve as she then was – would spend every waking moment together conceptualizing and talking about fashion theory. She had been the junior fashion editor at Harpers and when she left, they offered me her job. My tutors Felicity Green, Catherine Samuels, Geoffrey Aquilina Ross had slightly despaired of me. They kept trying to give me more downmarket assignments, ‘Why don’t you do a best-of-the-high-street kind of thing?’, and I would go off and do something unbelievably esoteric at C&A. Because I would elevate everything that was given to me.

It felt like Harpers was much more fashion forward than Vogue at that time.

It was halfway between Vogue and what Tina Brown was then doing at Tatler. It had that same irreverent in-house thing. Tina’s strapline was ‘The Magazine that Bites the Hand that Reads It’; Harpers was a sort of haughtier version of that, I suppose. But it was very fun and it suited me because our readership demographic was more a woman of substance. I felt it gave me licence to do quite a lot of ball-gown stories. When I first went in as a junior, I was doing the ‘Fashion Bazaar’ pages at the back of the book. At that point, there was a lot of logomania, and brands that were perceived as being a bit dusty like Gucci and Pucci were making those horse-bit loafers into an irony-redux thing, and there were a lot of young designers: BodyMap and Joe Casely-Hayford, Rifat Ozbek. That was the back of book. Then Nicholas Coleridge took over from Willie Landels as editor-in-chief and he asked me to lunch at the Caprice. There had been a slight revolving door of people coming and going since Vanessa de Lisle’s departure as fashion director, and I was being very productive and going off and doing lots of shoots, so he offered me the job. At the end of the lunch, Nick said, ‘Can you remind me how old you are?’ I said, ‘I’m 22, but nearly 23’, and he replied, ‘Promise me you will never tell any of our older advertisers that.’ So that was that. I was doing all the covers and the principal fashion stories and it was immense fun, working with people like Mapplethorpe and Angus McBean, David Seidner, a lot with Mario. We went around the world and did stories in Egypt, Peru, Brazil, Spain and Russia. It was extraordinary.

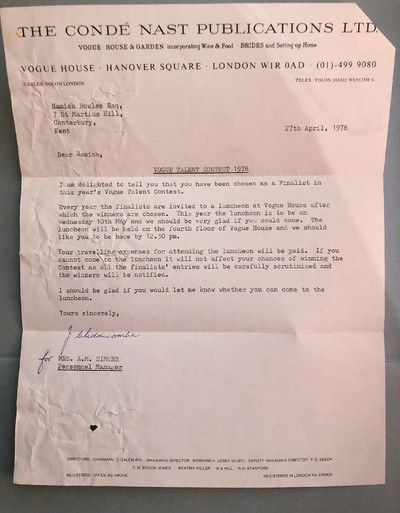

Letter to the 14-year-old Bowles announcing him as one of the finalists of the Vogue Talent Contest, 1978.

‘When I got a letter with the Vogue stamp on the envelope, it literally made my heart stop.’

It feels like such a shame that you never got a chance to work with Cecil Beaton.

You know, he was just not quite my generation, alas. He had been punched by Robert ‘Mad Boy’ Heber-Percy, and a bottle of perfume fell on his head and brought on a stroke. He didn’t live as long as he might have lived. I think he was 76 when he died. I was already totally obsessed, of course, from a very early age. I found a copy of The Glass of Fashion in a jumble sale and read it voraciously one summer holiday with my dad, while we drove round Britain in a VW camper van with an itinerary I had given him entirely predicated on the location of costume museums. He was very long suffering. The sale of the contents of Beaton’s house, Reddish, in Broad Chalke, was my first-ever trip away from home; I took buses across country. I was 14, staying in a bed and breakfast, and it was revelatory, going to see the house. I went to the churchyard in the village and found his grave, and was sobbing.

What do you think triggered your obsession?

I remember very vividly my mother taking me to see My Fair Lady at the cinema in Canterbury. I must have been seven or eight, I think, when that opening credit came up with an impressive job description for Cecil Beaton – sets, decor, costumes, art direction, whatever – and I very vividly remember her explaining to me who he was. Then I was a little bit sniffy about My Fair Lady because I thought it was a poor show that those Edwardian ladies had been given Cleopatra winged eye make-up and Eliza, in Mrs Higgins’ conservatory, was wearing a dress that Marc Bohan might have designed for Dior in 1964…

‘The sale of the contents of Beaton’s house was my first trip away from home; I was 14 and took buses across country. I found his grave, and was sobbing.’

So you knew all of this already? At seven or eight years, you were picking apart the visual inaccuracies of My Fair Lady?

Yes, absolutely. I mean now I can see that it was deliberately for theatrical effect, but I was highly unamused at that point, because I was fully immersed in more of a Piero Tosi world of absolute scrupulous accuracy.

How was a seven-year-old exposed to Piero Tosi, for Pietro’s sake?

Well, I got obsessed because the colour supplements had a big story on Ludwig, which I admittedly didn’t see for a while. I saw the pictures of Romy Schneider. I think Snowdon was the art director of the Sunday Times Magazine, and he put a lot of the film’s costumes into it. I certainly saw Death in Venice; don’t ask me how. Actually, there was a Visconti series at Kent University in Canterbury, which I went to see. I remember The Innocent. I didn’t see the realist early ones until a bit later. I was completely obsessed with costume and everything being scrupulously accurate and not stagy. It is so crazy to think of that now.

From what I understand, you were essentially rummaging around and finding bits of costume as soon as you could walk. I know you had very supportive parents, but they were hardly of that world. What do you think was your Rosebud?

I was very lucky in that when I was aged between four and nine, we lived in Hampstead Garden Suburb and our next-door neighbour was Dr Ann Saunders who was the secretary of the Costume Society and she could see that I had an interest that she then fuelled. She gave me those Winsor & Newton costume books you could colour in, period silhouette paper dolls from the V&A, all that kind of thing. I was obsessed with those. I think that my Rosebud moment was probably a couple of things. My mum remembers me, at about four, when there was an Indian woman walking towards us in a sari, and I was obsessed with it; I had to feel it because it seemed like it was made of spun gold, such a magical thing. Mum had a dress in the back of her closet, a cerise taffeta off-the-shoulder, short evening dress. Polly Peck, though it was actually a Dior copy. It had two sets of bows, two straps and bow ties on each bare shoulder. I used to dress up in that and it smelled delicious and made a satisfying taffeta sound as you swished it around. It was such a surprising thing because it didn’t seem to relate to the woman that I knew, who had gone through a very 1960s transition at that point and was wearing crushed velvet and patchouli and skinny-rib sweaters with no bra underneath. It just seemed a magical thing that there was this other life that this dress could tell me about.

‘And I’m sure you know the story about when Sadler’s Wells did a jumble sale to raise funds and I found a Balenciaga suit for 50p…’

An early lesson in the transformative power of fashion.

Yes, I would say that, very much so. I saw the sari; I found this dress. I went to see Coppélia and was obsessed with all the peasant girl, multicolour ribbons swirling around. All of it signalling all the different messages that clothing could convey and how powerful it could be. And at the time I read so much. I was reading all the historical books by Jean Plaidy, Tudor England and that sort of thing. I was really obsessed by what the characters were wearing and how they looked. That was such an important part of reading any kind of historical novel, being able to evoke in my mind just exactly how the characters were dressed. I started going to the V&A costume court, and then all those costume museums, in particular the one that Doris Langley-Moore had done in Bath, because everything was in dioramas, so it was like those books had come to life. There would be some sedan chair and livery footmen transporting the lady.

When did the interest expand to contemporary fashion? Your father told a story about you identifying a Balenciaga at the age of eight or so.

Something like that.

How?

The key costume museums were the V&A, the Museum of Costume in Bath, and then Castle Howard had a costume court, and Platt Hall in Manchester. In those days, in a lot of stately homes, there would be a dusty bedroom with half a dozen 18th-century dresses on makeshift stands. I had started collecting fashion, from going with my mum to junk shops. She was totally obsessed with junk shops and antique shops, and we would play this game. My father would be driving the car and if we saw a junk shop we would scream and he would screech to a halt with life-threatening urgency. We’d jump out and hold hands and rush into the shop, while he would wait in the car, absolutely furious.

What a fabulous dad.

That must have been when I was very young, because they separated when I was nine. And then I would buy, with my pocket money, little things that told a story. Edwardian gloves, glove stretchers or crimping irons or a pair of 1920s dance shoes, and then I started getting things at jumble sales. I had a stripped-pine chest of drawers and the bottom drawer would house all these treasures. I had a card-index filing system which, thank god, my father kept, with little cards that would say things like, ‘Edwardian lace fan, tortoiseshell handle, circa 1905, 20p, Bexhill-on-Sea, jumble sale’ and the date. Then a little thing about it. It got a bit more advanced. Through Dr Ann Saunders, I eventually joined the Costume Society myself. I was obviously their youngest-ever member and I would go to seminars – which was another completely crazy thought – on how to create little acid-free tissue paper pads to store things. I remember there was a woman called Imogen Nichols who had a costume collection. I befriended all these older women – I considered them old ladies – who had collections of clothes. Imogen lived in a village in Kent and she would occasionally do a costume exhibit in the local church hall. One time she did a sort of fundraising fete for the church, stands of pickles and jams and some clothes, and I got a suit that someone had donated by a London couturier called Ronald Paterson, which was quite Balenciaga: a cream silk three-piece with black penny spots. I do remember that the flat buttons had all been covered so that the penny spot was in the centre of each button. Very couture. I thought that was fabulous. I was reading about all of this in The Glass of Fashion, so I knew who Balenciaga and Chanel and Dior and all these taste-making ladies were. I’d go to Little Venice in the hope of catching a glimpse of Diana Cooper. I never did, though I did see Cathleen Nesbitt in South Kensington, which got me very excited.

‘The boys at my school in Highgate wore pork-pie hats and two-tone suits and would go to Madness concerts and shag girls from Camden High.’

Did you ever see Diana Cooper?

Yes, I did see her at a couple of shows. I must have been on my foundation course at Saint Martins or between my sixth form. I went to the opening night of Another Country, and Nicky Haslam was escorting Diana Cooper and my excitement could not be contained. Sure enough, she had that sailor’s hat with the diamond brooch. She was absolutely the part… And I’m sure you know the story when Sadler’s Wells did a jumble sale to raise funds and I found a Balenciaga suit for 50p…

And you’ve still got it, of course.

Still got it, yes.

What would it be worth now?

Well, more than 50p. But they are still remarkably reasonably priced. That was very exciting.

What was the urge to collect, do you think? Was it to possess?

I just found it very exciting to have these tangible objects. I found them so potent. I think at the beginning it was just the idea of the stories that sartorial objects could tell you about the time in which they were created, the circumstances in which they might have been worn. If you look at a 1912 Poiret or a 1903 Worth or a 1926 Chanel, you understand so much of what was happening at the time. I enjoyed it for that, although I wanted to hold on to those memories in a way. I think that is probably what stirred me in the beginning, combined with how excited and energized I had been by going to these costume museums around the country.

‘I was going to the Cha-Cha Club and meeting Leigh Bowery and Trojan. Leigh called me Miss Beaton funnily enough – he didn’t miss a trick.’

Were you a difficult child?

Not, not difficult, but very single-minded. I realize now that it is quite an unusual gift to be so uniquely focused on what interests you at such an early age.

Obsessed, as you said.

I could use that word, too. I think my parents saw that, too, and encouraged it. I look back at my 12-year-old self and I was interested in exactly the same things as I am interested in now. For my parents, it was just what life was at the time, but now I look back and it was unusual.

How did your peers treat you?

I kept that side of my life quite private to a certain extent. I mean, the girlfriends I had grown up with, they were excited by it. They got corralled into acting in the plays that I had written, primarily to showcase costumes. But when I started going to secondary school and realized that a lot of the things I was interested in were outside the usual remit of a 13-year-old British schoolboy, I kept it to myself.

You didn’t like secondary school?

Yes and no. I went to two secondary schools, a grammar school in Canterbury and then another school for sixth form when we moved back to London. I enjoyed the first one because I was passionate about English and history and art, and I had great inspiring teachers, and I was very into it. I had a fairly robust network of friends. I was becoming more and more interested in fashion, which I think came from seeing copies of British Vogue. I was excited by the world evoked, particularly in the more narrative stories that I now recognize were largely corralled into place by Grace Coddington, working with photographers like Helmut Newton and David Bailey. I think I was 10 when the first Vogue really spoke to me: it was a Bailey cover of Anjelica Huston and Manolo Blahnik caught in a not-entirely convincing – in retrospect – embrace on a beach in the south of France, and there was this whole narrative of a triangular relationship. Not that I would have been aware of that. I know that Anjelica was wearing a Bruce Oldfield jersey dress on the cover. He must have just graduated from Saint Martins at that point.

My mum was teaching catering before she did photography. She took out a lot of Vogues from the library and she would bring them home, and that really fuelled my interest. But no, it started even earlier than that, because there was a shop called Chic of Hampstead in Hampstead, and Mum would go there and window-shop and I would do the same. It had very nice sales ladies and I think they were surprised by this little boy who wanted to know so much, and they would pull things out and explain who the designer was. And that is how I partly began to know about Jean Muir and John Bates and Zandra Rhodes, Thea Porter, those kinds of people. Then I got a book – I don’t know how – that was a compendium of London fashion stores, like an A-Z, and basically I went through it and set off to visit all of them. There was a store in Notting Hill run by Shirley Russell where she sold clothes she’d bought for the extras in The Boyfriend, directed by her husband Ken Russell. Through this funny tome I discovered all these shops. I caught buses all over London, from Portobello to South Molton Street, and ticked them all off. So that book would be a Rosebud.

‘The next thing I knew, I’m going to Saint Laurent couture shows and meeting the most extraordinary ladies – the ones I’d previously idolized from afar.’

What was your presentation at the time?

Well, it was very schoolboy, not very flamboyant. It was quite old-fashioned, I suppose. We had school uniforms; I wasn’t really going crazy. I kept this world of costume and fashion apart from my school life. There was a collision when I was 14 and I noticed that British Vogue had an annual talent competition, so I wrote in. You had to write an autobiography in 400 words or less. It would make very excruciating reading now. I think I kept it though. I do remember one of the questions was, ‘Which person, living or dead, has most inspired you?’ and I wrote about Cecil Beaton. And then it was, ‘Which four fashions in this issue would you most like to wear or see your friends wearing?’ and I wrote about that. And anyway, I put it in a little envelope, and then duly got a letter in our letterbox in Canterbury with the Vogue stamp on the envelope. It literally made my heart stop. The letter said I had been chosen as one of the finalists and would I come to the lunch at Vogue House in Hanover Square? Which I did and there were two very nice editors, one was Mandy Clapperton, who I remember was wearing crêpe de chine and a Panama hat, and the other, Liz Tilberis, who was very jolly and nice. And the editor-in-chief Bea Miller who was quite frightening. We all sat down at the table and I had some Buck’s Fizz. I was only 14, and my mother always said that turned my head. Literally, a sip of Buck’s Fizz at Vogue House turned my head forever. It’s so funny that here I am back again. My school did a rather dreary annual magazine and the student editors asked me to write about this thing. I produced this unbelievably over-the-top story about my day in the metropolis; that was really the first time my private world collided with my school life. It was an absolute disaster and all the mums of my friends said, ‘This boy is a very unwholesome influence’, and that was that. So I sort of retreated back into my shell. Quite soon after, we moved back to London. I was very much a country mouse at that point, very inward facing, and I arrived in a school in Highgate with unbelievably sophisticated boys who were in pork-pie hats and two-tone suits and would go to Madness concerts and shag girls from Camden High. I was just so frowsy and out of it. That was a kind of weird period. I was reading in magazines about this exciting New Romantic life that was happening just down the street, and I remember thinking that would be exciting, but I was excruciatingly shy.

Were you bullied?

Quite badly at that school, weirdly because I was quite grown up at that point. Then also because I was a very diligent student, a swot. The first English lesson there I’ll never forget. We had been given an assignment over the summer, which I was quite proud of. I thought I had done quite well and the teacher came in and just started berating the class saying, ‘If you think this is how you are going to continue the sixth form then you have another thing coming.’ He went on and on, and I was a bit crestfallen and then he added, ‘Apart from our new student who has really applied himself and understood the assignment.’ My life was a misery after that. Then I just learned that I had better compartmentalize my different lives. I was going to Costume Society events and I made sure there was no crossover with school life. All my friends were much older people. I was busy swotting for my principal study English to go to university. I had a horrible relationship with the art teacher, so I went off and did a portfolio on my own, basically, and applied to Saint Martins for a foundation course, and they more or less said, ‘Why didn’t you apply directly to the fashion department?’ They implied that I might be accepted. At the time I was torn between doing costume design à la Piero Tosi, theatre design or fashion. So I thought I should do a foundation course and sort myself out. Meanwhile, the total expectation from school and my dad was that I would go to Oxford and read English. Then I got accepted at Saint Martins. I just thought that university would be a continuation of my school life, which had not been enjoyable at that point, and that Saint Martins might be something different. My parents were dumbfounded. Luckily that was back in the day of government grants [for university students] and I could get in through that process. I will never forget the induction day with all these Sloane-y girls, but then I mentioned Cecil Beaton and everyone knew what I was talking about, and that was incredible. Then I realized that I was suddenly surrounded by some like-minded spirits. Within a few days, I also realized that the life of the party was the fashion department, so dreams of theatre design evaporated at that point. There was a brilliant student called John Galliano who everyone was so excited about. He was the star of his year, a couple of years ahead of me. So I stayed on there to do my fashion course. The whole Saint Martins was just the most liberating thing. Suddenly everyone understood who I was. I realized that I wasn’t just this weird loner, that there was a tribe. It was like the chrysalis shell came off and I came out. Then it was going to the Cha Cha Club and Camden Palace and meeting Leigh Bowery and Trojan, and seeing all these new possibilities. I got on very well with Leigh who called me Miss Beaton funnily enough, because he didn’t miss a trick.

What do you think it was about Beaton that obsessed you so?

I think the multitasking, the fact that he dipped into the fashion world and society and wrote these very evocative diaries and wonderfully evocative books and designed and took photographs. It was the fact of these accomplishments in all these fields, and, probably more subliminally at that point, the drive and the productiveness.

Was the notion of self-invention, the way he remade himself, intriguing to you?

Yes. I particularly love that he lobbied the local authority to have the Sussex Gardens postcode changed from W2 to W1, unsuccessfully, at the age of 12 or something. I can relate to that. I was fiercely snobbish. Not snobbish in a social way, but more about things and people with unusual talent and drive.

Another enduring fascination with Beaton is the coterie, the Bright Young Things. Were you conscious of that?

I was obsessed with all these great beauties of the past, and I was always very envious that Beaton had his sisters Nancy and Baba and he could dress them up and photograph them. My sister resisted any attempt in that direction. She was having none of it. Then, at Saint Martins I found this gaggle of girls who I could be Pygmalion with, and that was exciting, too. Yes, Saint Martins totally turned my world upside down. Because I had just compartmentalized everything. At school, I was going off and seeing John Waters programmes and going to the Scala and seeing Fassbinder films, but I never could have brought any of that into my school life. I was a loner because there was no one else, no kindred spirit at all. Well, certainly none that I found. Funnily enough, the circle of friends at my previous school, whose parents had encouraged them to steer clear of this abomination, all blossomed and flourished in their subsequent sixth form and all very much embraced their sexualities.

Did you feel destined for greatness at any point?

No, I never thought about anything in a grand plan kind of way at all. There were just the things I was interested in and I found out as much as I could about them. I would say that the Vogue talent contest gave me a sense that this could be a career, that there was a life out there. But I didn’t really think about it. It just tumbled into place, and the next thing I knew, I’m going to Saint Laurent couture shows and meeting the most extraordinary ladies. It took me a long time to realize – probably in retrospect – that actually my contemporaries and the friends in my circles were every bit as extraordinary as the people in the past who I had idolized. I didn’t need to live in the past because the present was just as exciting.

‘There was so little separation between my role at Vogue and my life. Both folded one into the other. My work represented my interests, and vice versa.’

Do you think there is something melancholic about clothes that have been worn and treasured?

When the person who has worn them is no longer there, they become almost like ghosts in a way.

I don’t think about death when I look at old clothes; I think about life and the lives that were led in them. That is why it is so exciting when things come to me with provenance, particularly at this time when more and more people are coming and saying ‘I have my mother-in-law’s clothes’ and that is just so exciting because when you really have a sense of the person whose clothes they were, what their houses looked like, how they lived and entertained and decorated, with their husbands or lovers or partners, I just think that is so potent. You know, being able to flesh out the story. Quite early on, I had a lot of things that belonged to Aileen Plunket, who was one of the Jazz Age Guinness sisters, who lived and entertained in Luttrellstown Castle, outside Dublin, which was the de facto entertaining house for the Irish government at a certain point. The way she ordered all these clothes in particular colours that were calculated to flatter her looks, and the decor was also designed in the same colour. I met her as well, a fascinating flibbertigibbet, with all these wonderful photo albums that she showed me of all the great Jazz Age figures. It was exciting to see what all these clothes had done, otherwise it was speculation. Just to have a real sense… I mean, she would fly to Paris to have Alexandre curl her eyelashes in the late 1950s. Wild extravagance.

You’re very precious with your things. I remember the little vignette about you taking care not to expose dresses to the light.

It is just one of those things, you’re acquiring and accumulating, and then suddenly you realize in fact you have a collection that needs to be sustained and maintained, and the whole point of acquiring these things is to preserve them and that requires proper infrastructure, climate-controlled spaces, acid-free boxes and paper, and pest-control strategies. It is like a real responsibility.

What did you make of Kim Kardashian in Marilyn Monroe’s dress?

There was a prickle down my spine. I mean, I understood the protocols; I knew it was going to be worn for a very finite amount of time.

But Marilyn was sewn into it and then presumably picked out of it. So there must have been something done to that dress that wasn’t particularly curatorial.

There was a stole that hid the back, of course, and a very, very dramatic weight loss. And there was a replica to change into for her to actually wear. But yes, I wouldn’t be lending something from my collection.

Scandal though that was, it was a huge testament to the iconic power of certain pieces of clothing.

I see the point. You’re thinking about an exhibition that celebrates American fashion and what is the most iconic piece of American fashion? Or Franco-American fashion, actually.

‘Aileen Plunket, one of the Jazz Age Guinness sisters, would fly to Paris in the late 1950s to have Alexandre curl her eyelashes. Wild extravagance.’

I feel like you’ve met absolutely everybody. Who thrilled you the most?

You know, Leigh Bowery was quite thrilling; I might have been less aware of it at the time, but he had an incredible energy. Izzy Blow was a very thrilling person. I was thrilled to meet people like Madame Grès, Saint Laurent, Cardin, Givenchy. At a certain moment, it was exciting to meet people like São [Schlumberger] and Lee [Radziwill] and C.Z.; all these women I had idolized from afar. Anne Bass, Ann Getty, Deeda Blair. Also, to realize how lucky I’ve been with the people more immediately in my life, my parents – that is ultimately the takeaway, because a lot of these people have very conflicted and difficult relationships with their children. That seems to be a leitmotif with style mavens through the centuries. They are compelled by certain aspects of their lives, and so sometimes their children are a little bit neglected. So I realize that I was very lucky to be dipping into those worlds, but also to have parallel lives.

Your mother sounds absolutely wonderful.

They really broke the mould with her. She was a marvellous person. One takes so much for granted with your parents. I am very much a combination of them. I got theatre, literature, English very much from my father. Mum was a much more intrepid version of me; she certainly had wanderlust, and she encouraged me. There were very strong ideas about style, and about good values and what was real. I sort of realize now how closely I am linked to them.

You talk about style mavens having difficult relationships with their children. There is something generally unkind about the fashion industry.

There are very kind people in it, but it’s ruthless on some levels. When I started at Saint Martins, I wanted to become a designer. I spent all my childhood sketching. I have thousands and thousands of fashion sketches and costume designs. I look at them now, and I actually think they are kind of amazing. I was astounded by how prolific I was, and obsessed. But I think it is more interesting to be an observer looking in and understanding very different processes and different designers.

Do you feel like you are the Beaton de nos jours?

I don’t know if that is for me to say. I mean, there are talents I don’t have. I wish I could take pictures and photographs, and I certainly wish I had kept diaries. Although I have every last bit of ephemera, every place card, invitation and so on. All my appointment books – they will be very useful for unravelling things – and there’s every Polaroid of every fashion shoot, which mainly involved me standing in for the model, while they had their hair and make-up done. So it’s me as Naomi, and Gail Elliot and Cecilia Chancellor and Yasmin Le Bon.

‘Beaton lobbied the local authority to have the Sussex Gardens postcode changed from W2 to W1, unsuccessfully, at the age of 12; I can relate to that.’

You were showing me things on the board behind you, and I had a little look when you left the room. I was curious as to what your sense of imposing your personality on the magazine actually involves.

It happens by default. I’m realizing that a large part of this job is constant decision-making – having a response to questions and options that are presented to you all through the day – so it just does have to be instinctive up to a certain point. I didn’t set out with some egomaniacal vision but it does become very personal because it is all about one’s taste and you are making these judgement calls. They might not always be the right calls, but the buck certainly stops here. When the images come in and you are putting them all together, what sometimes happens is two stories that might have seemed very different in the scouting pictures or your memory of the environments suddenly have a strong resonance between them because of the way they have been photographed. Then one will have to be shunted into a subsequent issue, so that the flow of the magazine is more exhilarating, with a real variety of stories. The July issue, which you see on the boards, lent itself to this formula. There was traditionally an insert called ‘The World of Exteriors’ in the July issue, but this time we’ve shaped the whole issue around exteriors. It was challenging because there was no inventory of gardens, but it was quite easy to put in much more editorialized stories, like a portfolio of artists who simulate flowers in wax, ceramic or paper, or a story on an 1850s garden book that was the most expensive example of its kind at the time. There’s a story on the artist Pierre Bergian, who evokes these extraordinary rooms, some of them imagined and some storied. He painted his own apartment for our issue, and did some de Chirico-style exterior-scapes. We have been able to use those anchoring stories between more traditional house stories, and so on. So I think there will be more of that moving forward, with profiles and so on. We had Dame Magdalene Odundo in the June ‘Art and Antiques’ issue as a profile, which was a serendipity because I’d sat next to her at Thomas Dane’s gallery opening.

How often does that happen, a random serendipitous connection with someone which then generates the story?

It’s funny, things are just in the air. I’d been thinking a lot about Magdalene and then I heard she was going to be part of Thomas Dane’s group show, curated around the idea of clay and artists who work in that medium. Her work was juxtaposed with some early Fontana works and it was so poetic in the way it was installed. I was reminded of my great friend [antique dealer] Gordon Watson who had a fabulous apartment in Courtfield Gardens at the end of the 1980s. It made a great impression on me because he had Boltanski works and 1940s French furniture, a rug woven after Cocteau, and this very imposing table with five or six Magdalene vessels arranged on it. Her work was in my mind and when I sat next to her, she said that she considered a World of Interiors story on her practice in 1984 as a really significant moment in her career. It put her on the map. With all her other projects going on, including a dedicated space at the Venice Biennale and a lot of attention from the auction houses in her work, I thought it would be interesting to revisit the 1984 issue. We had it in our archives – they are very beautiful pictures – so we went back and did a portrait of her in her studio in Farnham, which we also documented, so we could fold it in. It was a way to relate what was exciting and happening now to the magazine’s history in this powerful way. As I said, things are just in the air. Suddenly, three of my revered contributors will come to me and say, ‘Oh my god, I have just seen such and such a place and you really have to do something.’ That is exciting.

‘I didn’t set out with some egomaniacal vision for The World of Interiors, but it does become very personal because it’s all about one’s taste.’

In my experience of World of Interiors, its appetite for the arcane was thrilling. Of all the interiors magazines, it was the one where you would go to find, say, a story on William Beckford as opposed to a celebrity apartment. Are you naturally drawn to arcana?

I think I am. As a child, my interests, although they now might seem in some cases commonplace, were certainly esoteric for a boy my age. Some were and are still esoteric. I was mad about Captain Molyneux as a ten-year-old. I just thought it was so fascinating. Now, someone like Captain Molyneux, I think about him through a very different prism. If he had been able to parlay his romantic life and history in the way that became part of Chanel’s legacy, he might be a little more remembered.

With such esoteric boyhood pursuits, I need to know whether you also went to Carry On movies.

I loved Carry On movies! [Mock indignation] In fact, I made a pilgrimage to Kerry Taylor [auction house] to see Babs’s towelling bikini, which memorably malfunctioned in Carry On Camping. I had a particular soft spot for Charles Hawtrey and Kenneth Williams, for self-evident reasons.

You straddle universes. Coming back to Beaton, I think of him going home at night and making acid observations in his diary about all the failings of everyone he was compelled to spend time with. Being in his world but not of it, in a curious way. When you talk about preferring to be outside looking in, I wonder if you ever felt the same way as he clearly did.

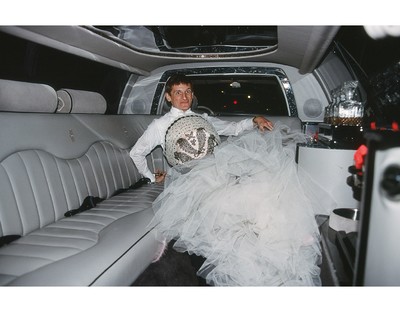

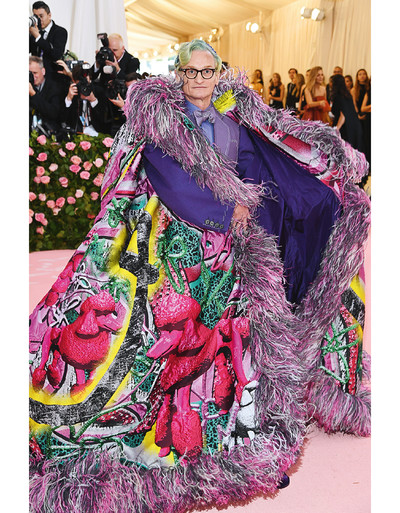

I don’t know if this is unusual necessarily, but it is very particular to me. I have always had very much a high-low sensibility, whether it was the Hotel Intercontinental and the Saint Laurent couture show, or RuPaul at the Pyramid Club in the mid-1980s. My life at Vogue has always been very much about going to dinner at Deeda Blair’s and having a soufflé presented with a ladle of caviar on top that collapses slowly into the souffle as you eat it and having a wonderful time and being saturated in her aesthetics, but then heading downtown and going to the club of the moment until five in the morning…

Don’t say the Mineshaft.

I wouldn’t say that, no! But whatever it might have been. My first experience of New York was with [jewellery designer] Vicki Sarge who was my roommate at the time. She had been on the door of the Mudd Club and was unusually connected to that world. So I arrived and we had an open sesame to the Mike Todd Room at the Palladium, which had just opened, and Area and Save the Robots and the Pyramid Club, and a party that Madonna would turn up to, all that incredible downtown world. Then the following morning, I would go uptown to Martha’s on Park Avenue because I was so fascinated by the women who would be shopping there; they’d be having a trunk show of the collection by a then-emerging Carolina Herrera, which looked like something from The Women – and that was my fantasy world. Bergdorf or Mortimer’s, seeing Mrs Kennedy on the front table, or Betsy Bloomingdale, or Pat Buckley holding court. I was just so enthralled by the wonder of all of it on all levels. My life was just one long pinch-me moment, everything was so exciting, seeing all these people I had seen in the pages of WWD come to life, initially from afar, and then in a much more intimate way, even becoming friends with some of them. And similarly in Paris, it was going to clubs like La Nouvelle Eve and Les Bains Douches, and getting into Le Privilège in the basement of Le Palace, and then being invited to São Schlumberger’s as a pic à dents – or toothpick, meaning you showed up after dinner – where she’d said the dress code was informal, and yet she greeted her guests wearing Colombian emeralds and that Saint Laurent yellow duchess satin jacket with Lesage grapes as epaulettes. Though I do suppose the skirt was a short, not a long one.

And what would you be wearing for that?

I’m wondering what I would have worn for that. I did have a purple Mugler suit that was trellised with chartreuse and I might have brought that out. Or a Gaultier something or other.

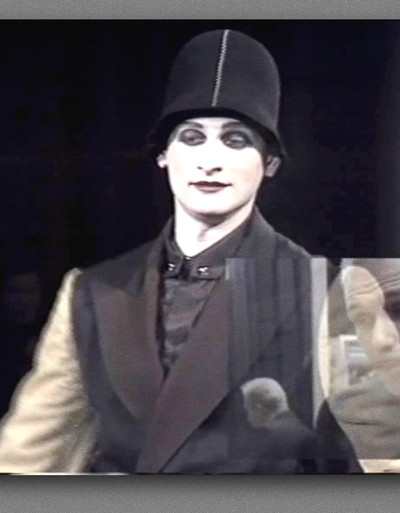

Ah, the memory. You were in that Gaultier show in 1989.

I was, I was revelling with Jean Paul and his press officer Lionel Vermeil, who looked like an Otto Dix character with a lot of fox furs and kohled eyes and thin as a whip. He sidled up to me at four in the morning and said, ‘Jean Paul is wondering if you’d like to be in his upcoming show.’ Of course, my cup literally just ran over. There was a pause for theatrical effect before Lionel added, ‘It’s based on Weimar lesbians.’

And you were such a Weimar lesbian in that show!

That was very fun. I was at Harpers and I hadn’t told any of the team and they were all panicked that I hadn’t been able to make it to the show. It was at the other end of Paris and quite difficult to get to. And then they saw me flouncing down the runway. When I came off, I was told to be slightly less camp and more Weimar lesbian! If you watch the whole thing, I think I was a bit more subdued on my second and third passage.

‘In many respects, I am hopeless in a childlike way. I can’t drive; I can’t quite cope with technology. I certainly don’t feel the age written in my passport.’

How did your two worlds, high and low, feed each other to make you what you are?

First of all, the Vogue world, certainly in the 1990s, was a society that was evolving and so, of course, our focus was on society women who might have been exemplars of part of the 1980s razzle-dazzle but were now working with God’s Love We Deliver or raising funds for the New York Public Library. It was all very philanthropy-based. But you also wanted to know what parties Susanne Bartsch was throwing, who was going to them, what Todd Oldham’s apartment looked like in Chelsea, who were the exciting emerging artists. So everything fed how I saw the Vogue world, which was uptown and downtown. I am writing a memoir and I actually stop at my lunch with Anna after she offered me the job in 1992. I’d initially planned a much broader sweep but there was so much to write about the 1980s and the cusp of the 1990s, between Leigh Bowery and Princess Gloria TNT and Gianni [Versace] emerging and Karl at Chanel, and Marc [Jacobs] and Isaac [Mizrahi] in New York, and what AIDS and smack addiction did to everyone, and how that recalibrated our world. I got hooked on writing about all those characters and thought maybe I will just save everything else for volumes two and three.

So volume two will presumably be the Vogue years. You were brought in to cover interiors. Did you find that honed your interests or did it still allow you to express the breadth of your experience?

It was always unusual, because I brought seven years of fashion life behind me; it was not as though I checked that at the front door. I was also going to shows and profiling designers, so through the years, I kept the day job. I mean, I am still at Vogue. There was so little separation between my role at Vogue and my life. Everything folded one into the other. My work represented my interests, and vice versa. What was very different, of course, was that I had much more autonomy at Harpers & Queen because I was working with a series of editors who were probably more wordsmiths, and I was charged with running the fashion department and covers. So when I came back from the collections, I would say these are the 24 stories we are going to be doing over the next 6 months, and these are the 8 stories that I am going to be doing. Then to come into a very different structure, working with an editor who is extremely focused on every detail, every caption, every pair of earrings that needed to be chosen for a page, it was very different.

A different kind of education?

Yes, it was in a way, because you certainly discovered very quickly the kinds of things that were going to be warmly embraced, the kinds of things that were going to be a tough sell, and those that were never going to make the grade. So that was a recalibration right there. I think I could truthfully say I was very productive.

After so much experience, after acquiring this wealth of knowledge and wisdom, what do you envisage for the future? Do you still see yourself as an observer, or are you now more participant?

Both, I think. I certainly think that World of Interiors is kind of the dream because I can find in it so many of my interests and that is really exhilarating. I would also say, moving back to London is really recalibrating my life in a sense. Though Diana Vreeland said that the best thing about London is Paris, you do realize that a lot of places that I love to go are so accessible, especially now as I attempt to claw back some of my weekends.

And you have a new apartment to decorate.

Yes, so I need to travel the world and bring things back for that. I do at some point, in a complementary parallel way, want to focus on my collection and on bringing that to a wider audience, whether that is through books or exhibitions. Or both, ideally. That is a big focus for me, and that will happen totally in parallel to my life here.

You seemed like you were such an old soul as a child. How do you feel now?

I feel very, very young and immature in some ways. I think I lived my life backwards.

Hamish Bowles is Benjamin Button!

I mean in lots of ways, I am hopeless in a childlike way. I can’t drive; I can’t quite cope with technology. I certainly don’t feel the age that my passport tells me. But I have certainly learned from older – sometimes very, very much older – people who I really admire. What kept these people so young was an unquenchable curiosity about the world and life, and what was going on. I think that has always been my thing as well, and that is also what is so exciting about having one foot in the fashion world because it is constantly changing and reflecting a different zeitgeist.