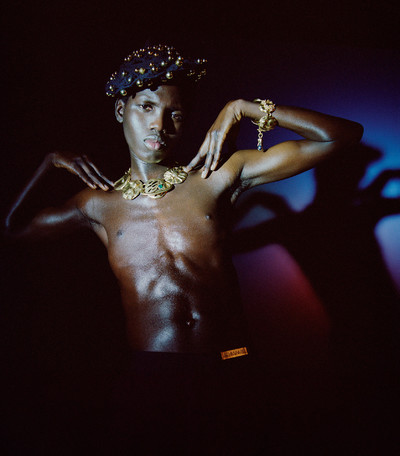

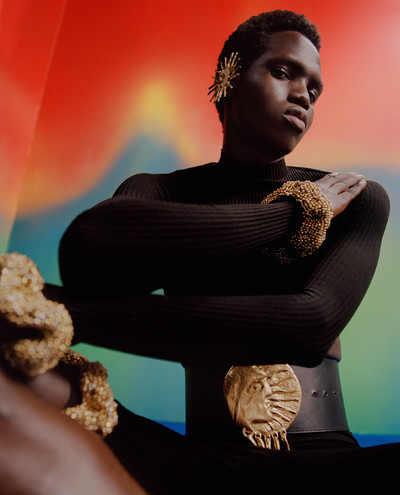

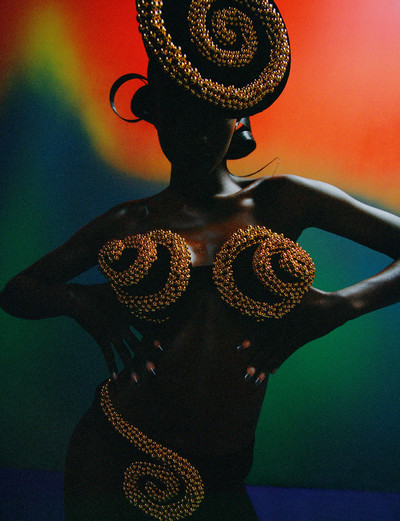

Daniel Roseberry’s own coming-of-age tale is bringing dramatic surrealism back to the house of Schiaparelli.

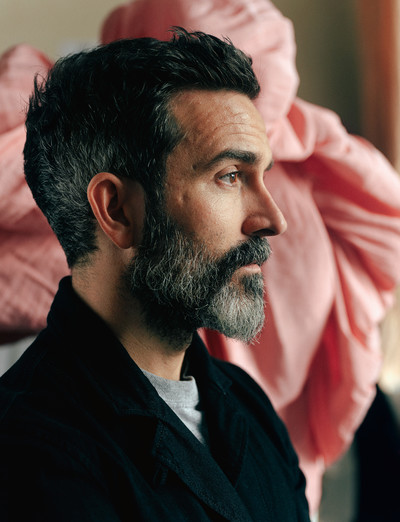

By Jerry Stafford

Photographs by Nadine Ijewere

Styling by Nell Kalonji

Portrait by Christophe Coënon

Daniel Roseberry’s own coming-of-age tale is bringing dramatic surrealism back to the house of Schiaparelli.

Daniel Roseberry is designing a new desk for his spacious office at Schiaparelli’s HQ, which looks out onto the grandiose symmetry of the Place Vendôme in Paris. After three challenging years at the helm of the legendary house, it feels like he is discreetly loosening his stays and slipping into something a little more comfortable. ‘It’s very much a work in progress,’ he says, almost tentatively, ‘but this is a signal that I am settling in!’

In the wake of the 2020 pandemic that threw everyone and everything into a maelstrom of confusion and self-doubt, Roseberry confidently burst back onto a newly reopened international stage last year with a series of sensational coups de théâtre worthy of the house’s illustrious founder, Elsa Schiaparelli.

In January 2021, at the inauguration of Joe Biden, Lady Gaga serenaded the newly elected President of the United States in a navy jacket by the designer, decorated with an extravagant gilded dove of peace, and a skirt that exploded into volumetric tiers of washed red silk faille. Seven months later, Roseberry’s reputation was further sealed with Bella Hadid’s other-worldly appearance on the red carpet at the Cannes Film Festival, wearing an exquisite gold bustier masterfully cast and crafted to represent a pair of life-giving lungs. The vision was pure Elsa and recalled her own celebrated collaborations with Salvador Dalí.

After long being starved of such spectacle, the fashion world gasped at the sight of this almost saintly apparition. The house of Schiaparelli was no longer just a whisper on Mae West’s lips!

‘The house of Schiaparelli is a singular thing,’ says performer Tilda Swinton, who has also worn Roseberry’s chimeric creations over the past year. ‘The landscape of its legacy – the practical magic of its resonance – is something almost mythical in the wide geography of the fashion universe. Schiaparelli means an intimate and ancient relationship between art and fashion, in particular with the vernacular of a Surrealism dear to the heart of Elsa Schiaparelli herself. In the hands of Daniel Roseberry, this resonance pulses with an energy and freshness that regularly takes the breath away.’

The designer’s latest couture collection – a palette-cleansing exercise in monochromatic minimalist maximalism – was his first live presentation since Covid had sent everyone racing into the metaverse. Monolithic dresses stalked the runway like charismatic megafauna beamed down from outer space into a Kubrickian dreamscape.

Roseberry recently launched his first ready-to-wear collections, sold exclusively through Bergdorf Goodman, which both complement and extend his couture process and creative vision. The iconic Surrealist signifiers and stylistic hybridisation of his couture collections have now been integrated into clothes and accessories to accompany the new Schiaparelli woman as she descends from her gilded pedestal and steps into the ‘real world’.

As a designer, Roseberry seems to find inspiration in a narrative that has its roots in his childhood. His own sentimental education reads like a dramatically charged coming-of-age novel in which the protagonist ultimately achieves self-awareness and self-confidence through art and creativity.

Geography has played an important role in that journey, and those places with which he has fallen in or out of love have influenced both his life choices – or his ‘forks in the road’, as he calls them – and his sensibility: the claustrophobia of his upbringing in Dallas, Texas; the revelation of the New York years working alongside Thom Browne; and the escapism of the coastline of Maine which, as he explains is, ‘the place where I think I first met myself as an adult, and ironically, it’s the place I run to when I want to feel like a kid again.’

Hanya Yanigahara, the acclaimed author of bestseller A Little Life, recently dedicated her new dystopian epic To Paradise to Roseberry and they share an intimate, intuitive relationship. ‘When you’re a writer, you write when you feel like it,’ Yanigahara explains, ‘and (ideally) only when you feel like it. Daniel and his peers don’t have that luxury. Some artistic directors turn their gaze outward in response, always looking for something to inspire them, but some – and I believe that, ultimately, Daniel belongs in this category – venture ever-further inward, to an emotional landscape they’ve created and tend year after year. They’re constantly harvesting from this invented world, one accessible only to them. It’s a special way to create, but a punishing one as well. For the most imaginative among them, though, the results are unmistakable and undeniable.’

Let’s start by discussing where you grew up, your childhood, and your home life.

Daniel Roseberry: I grew up in Texas, in a middle-class suburb of Dallas. My dad was a preacher in a church that he founded the year I was born, which became a mega-church of sorts. Both of my parents were born-again Christians; they were not brought up religiously but met at the seminary. My mum had two kids from a prior marriage and then they had me and my little sister. I guess my childhood was one of searching, of longing. I went to a private school in Dallas where everyone had tons and tons of money. We basically had none. I was daydreaming all the time of the things we couldn’t have.

What are your earliest visual memories?

Daniel Roseberry: I remember watching my mum getting dressed for church, putting on her jewellery. I also remember playing with my sister in a pile of fallen leaves near my parents’ house. In the fall. A lot of my early memories are related to fall.

What or who were your first sexual or sensual fantasies?

Daniel Roseberry: Good question. I remember being in seventh or eighth grade and I was sleeping over at my friend’s house. We were lying on the bed and talking about this sex scene in a movie, and for the first time, I confessed to him that I had loved the movie, but that I couldn’t stop looking at the boy. He thought that was really weird, and I don’t think it was ever the same between us again. That was the first time I remember verbalising something homoerotic.

Who was the actor?

Daniel Roseberry: I don’t remember… oh, it was the shower scene in that terrible but amazing movie with Kurt Russell called Captain Ron.

How did you experience growing up as a young gay man in the southern states of America?

Daniel Roseberry: Tortuous is a dramatic word, but it was sort of tortuous. It was a journey of deep self-hatred and thinking that I was a broken and failed heterosexual. That was the message: this is in God’s best interest for you; you are a failed version of what you should have been and it’s your job to bring yourself back to a general semblance of normality; if not, then celibacy would be the ideal solution.

Did you yearn to leave that environment and if so, to go where and why?

Daniel Roseberry: I was so terrified. I remember when I was at school, in my freshman year at college, and I had got into FIT, but rejected the idea of going twice because I was so scared of going to New York and falling into some crazy drugs scene and sex den.

You were scared of actually living the life you desired.

Daniel Roseberry: Yes, yes. Everyone processes their rebellion in a different way, and I was so cautious and nervous because I didn’t want to disappoint anybody. I remember being a freshman and I was sitting alone reading W magazine and there was a story on Tom Ford, with a Steven Klein shoot. I was filled with so much confusion and fear, and also longing. New York was a really difficult decision to make. I was a Christian missionary for a year prior to moving to New York – I really did try every option.

‘I got into FIT, but rejected the idea of going twice because I was so scared of going to New York and falling into some crazy drugs scene and sex den.’

Were you exposed to art growing up? You were brought up in Texas, so were you aware of the Menil Collection, for example, or the other great art institutions in the state?

Daniel Roseberry: I remember when the Nasher opened, that was a big deal. I come from a family of artists: my mom and my grandmothers on both sides and two of my uncles were extremely prolific artists. That was the foil to all the religious and spiritual dogma; there was always an appreciation for that world. I remember my grandmother had expensive museum catalogues, which were really inspiring for me, but I always felt really out of my depth talking about current modern art.

Who were your favourite writers back then?

Daniel Roseberry: I had a very classic education. I was really into Dickens, Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. I have this thing with Hanya Yanagihara called EGS, which stands for ‘exquisite gay sorrow’. We’re always talking about what triggers EGS, like did you have an EGS sort of a day? A lot of the writing I was drawn to that pre-dated this life was very EGS.

Was music an important part of your life at that time?

Daniel Roseberry: Music hit me after, like mid-high school and after high school. Before that I was obsessed with the movies, and I wanted to be a Disney animator. So it wasn’t until I moved to New York when music completely replaced cinema as my number-one inspiration.

Where or what was your first encounter with what could be termed as fashion? The one that made you feel it was an area of interest that could possibly take you somewhere?

Daniel Roseberry: I started to draw women and clothes before this moment, but the real moment happened when I was 16. Style Network came to Texas, and they did a free bundle, with Fashion File, Behind the Velvet Ropes, all those things. There was a special on Michael Kors and I saw in detail the journey of his collection, and at the same time learned that he was from a similar middle-class background. He had gone to FIT and dropped out, and then his collection was on display at Barneys, and someone came and bought it, some crazy story like that. And I was like, ‘OK, I could do that.’

What about your own personal style at that time? Did you follow any trends or movements?

Daniel Roseberry: I have always been a bit clueless about what to do with my own style and talking to you, it’s so obvious, there are some people whose style and physicality are totally embedded with who they are. I just never felt like that. I remember watching the McQueen collections and then he would come out at the end, and the disconnect really resonated with me. I have never successfully been able to dress myself in an identifiable style. That is why Thom Browne was such a relief. Of course, I’d been in uniform since second grade. So through Thom Browne I learned everything.

What do you think was your real motivation behind this interest in design and fashion?

Daniel Roseberry: The answer is not very glamourous, but it was a way for me to justify my own existence; I think that being told that your identity is wrong…

As in your sexual identity?

Daniel Roseberry: My sexuality, which felt like my entire being. Design and the ability to wow people and to impress them, and to give them something else to applaud me for because I knew they would never applaud me for the decisions in my personal life – that became a huge motivating factor.

Did you ever have a mentor or someone who actively encouraged you in your studies and then your career?

Daniel Roseberry: Mentors have thankfully been a huge part of my life. At every step of the way I have had someone mentoring me; I have never been on my own. The first one was my mom, who taught me how to draw for hours and hours; she would stand over my shoulder as I did artworks for doctors’ offices and stuff. Later there was the dean of the seminary who mentored me theologically and who also released me from a lot of this self-hatred. I almost went to seminary, and he told me absolutely not, you have to go to New York to be a designer. And then once in New York it was Thom, so yes, there have been lots of mentors.

Are you an ambitious person or are you more intuitive? Have you been drawn almost inexplicably and unconsciously towards the future and your place in it?

Daniel Roseberry: I know this sounds insane, but I always felt that the hand of God has been in my life from the beginning. I have always felt like this; I didn’t really have a say. I felt that fashion chose me in a way, and I have been toiling to get to this place. I have never even considered doing anything else.

Are you still a practising Christian? Do you still believe in a Christian God?

Daniel Roseberry: I believe that the Christian God is a mechanism by which I can understand God, but I do not at all prescribe to the narrowness of a Christian faith. I do also believe that Jesus represents one aspect of maybe the way that God or a creator wants to relate to the world, but I don’t know if I would call myself a Christian any more.

Jumping forward, how did you navigate the move to Paris from the States in 2019, and what is your relationship to the city? How do you fit in here?

Daniel Roseberry: I had prepared my life in New York so I could abandon it. I had already moved out of my apartment, and I was sleeping on a friend’s floor. Everything I owned was already in storage because I really believed this job was mine. When it happened, I literally came here with two suitcases. Everything else I own is still in storage in New York. Looking back on my arrival in Paris, I was so glad that I really had no idea what it meant to be doing my first collection. I had no idea, and the great thing was that no one really had any expectations because the house was so sleepy at the time. My relationship with Paris has been really rough, though. I really feel like a stranger in this city; I have never lived somewhere and felt like this. New York was such an amazing life; it was so rich. I had friendships; I had Sunday-night dinners; I was surrounded by people who loved me, and I always entertained at my house. I have never spent more time alone than I have here over the past three years.

How would you sum up that time when you lived and worked in New York, the changes that you experienced in the city, the shifting political framework and creative challenges?

Daniel Roseberry: I was 23 when I started at Thom Browne. I came out to my parents a week before I started my internship. I was in the closet throughout college, completely shut down, so I was really born then, this second birth, the second coming out. In those first five or six years at Thom Browne, when we were really building the foundation of that company, it was like the Wild West. It was unsupervised, plus my life in Brooklyn, it was such a dream. I look back at that time with such nostalgia. I had the best friends in Brooklyn. We have all disbanded now, everyone has scattered because of Covid and everything, but there was a summer in 2018 – or 2016, 2017, I can’t remember – when we went to Maine. At the end of that trip, something had shifted in my mind, and I thought: ‘I never am going to get to where I want to be in my career if I stay in this Brooklyn neverland world, and if I stay at Thom Browne.’ That was a turning point for me and within a few months I moved to the West Village in a studio and started over. I walked away from a lot, and I am extremely nostalgic for that.

Did you always aspire to head up an important historical fashion house? Was all the experience you acquired part of this ambition?

Daniel Roseberry: Yes, 100%. All of my years working at Thom were spent pining for my own thing, but I never thought it would be my own brand. I like the idea of being able to hide behind the heritage and the weight of something that existed before me.

Would you say that’s connected to your childhood?

Daniel Roseberry: Yes, completely. Something that is legitimising. It was really one of the most uncomfortable things when I left Thom Browne. It was not very long, just six or seven months, but I was so uncomfortable because I had nothing with which to justify myself to the world. You go to a party, and no one knows who you are; you are constantly having to justify your existence to people, especially in New York. So I always wanted it.

Now you are here in Paris and installed at Schiaparelli, what importance does the house’s history and heritage have for you? You’ve said that you have never read a biography of Elsa Schiaparelli, why?

Daniel Roseberry: When I first started I had no interest in tapping into the heritage because I felt it had already been the focal point of prior years. I really tried to re-establish the voice of the house and make it personal. When I felt that we had done that on some level, I was able to return to her work. I have been truly blown away, humbled and proven wrong about the relevance that her work still has. The more I reference her work and use it as a starting point, the better it makes my work. Her legacy feels like an untold story. The exhibition that is opening in July is the first step I think in maybe telling that story to a wider audience. She was the kind of person, with her voice and her personality and her character, who if I met her at a dinner party, I would be probably the most intimidated to talk to. That’s probably why I’ve refused to read her biographies.

Nonetheless, the house archive is an invaluable source for your work. How do you approach and navigate it and how has this research manifested itself in specific pieces?

Daniel Roseberry: What we do every season is go back to the archive. It’s mainly imagery because we don’t have physical archives here. They have a huge archive at the Met, I think, and most of the great pieces are at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; it has the lobster dress. We always print out all the imagery of, like, iconic Schiaparelli jackets or accessories – because she did these outrageous accessories, these titbits that went along with the collection – and we have them out as the collection grows. It all becomes the subtext for everything. There are normally one or two pieces that present themselves, like the teacup coat, which just felt right. And some time last year, being sort of literal with the archives suddenly felt fun, like the shoe on the head. Sometimes it is about abstracting it; other times, it is about holding it very tight and being literal. What I enjoy the most here is that with Chanel or Dior or definitely with Balenciaga, you don’t get a true personality like you do with Schiaparelli. You get a vision, you get savoir-faire and technique, and you get world-changing silhouettes – but you don’t get personality or a sense of humour. That is her greatest legacy, and what gives me permission to imbue that into the work as well.

You can be quite cavalier about it. Has the Surrealist movement, so important in Schiaparelli’s lifetime and to her work, been an influence on your own process or design? There are many signifiers, surreal objects, masks, and so on that are integrated into the clothes, but beyond that I feel that the way you have pieced together couture garments from the narratives of other designers is reminiscent of the Surrealist parlour game, the Exquisite Corpse. Was this in your mind during that process?

Daniel Roseberry: You’re the only person who has ever really verbalised that for me because it’s true the Surrealist movement, as an art movement, is far less inspiring than building a Surrealist process. That space where pre-associations can be made is like gymnastics, you know. That idea of collaging together different fetishisations of other designers’ work is something I try and be really open about, because it’s so obvious sometimes. It’s like when Virgil [Abloh] said, ‘You only need to change things 10%.’ I am definitely not trying to copy, but I love scratching that itch – like, what if we do something that is this designer on top and bottom, but the middle is Lacroix? I love playing that game.

‘I tried to re-establish the voice of the house and make it personal. When I felt that we had done that, I was able to return to Elsa’s work.’

It is a game, and it’s a wonderful one, whether visual or textual, as it’s a way of accessing the unconscious and opening oneself up to chance – ‘le hasard’! Something that intrigues me is that there are so many utterly compelling narratives around the history of the house, aside from the obvious relationships with Cocteau and Dalí. The poet and patron Edward James for example whom Schiaparelli called the ‘true English eccentric’. She remembers James giving Dalí a stuffed polar bear dyed shocking pink! Are any of these eccentrics that surrounded Schiaparelli attractive to you? Does eccentricity in itself inspire you?

Daniel Roseberry: That’s a great question. Yes, it does. What’s hard for me about eccentricity in other people is that I have a tough time accessing a real connection with it and that can kind of throw me off sometimes. My best friend, for example, is wildly eccentric; she’s living a life that is not really in accordance with the way other people live, and I find it endlessly inspiring to have those conversations, and to spend time with her and learn about that. I am very earthbound in the way that I live my life. We had that conversation about Edward James in Mexico, and I always think about that because I love that sensual side to Surrealism, which I think about a lot.

When I see your work I always think of artists like Méret Oppenheim, Louise Bourgeois, and more contemporary figures like David Altmejd or Sarah Lucas. Who were or are, of course, sculptors. Your work has often been called ‘sculptural’, for want of a better word, and you have collaborated with ceramicist and metallurgist artisans on specific pieces. Do you see these as collaborations, and do you enjoy the collaborative process? Would you work with an artist on a collaboration as so many people do these days in fashion?

Daniel Roseberry: I didn’t want to do collaborations at the beginning, because I didn’t want the legitimacy of the house or of me to be linked with or indebted to the collaborator. There are two types of collaborations: there is the process collaboration, which you go through with an artisan, which is a chain reaction of creative decisions informed by their skill set. I owe everything to that. Then there is the kind of collaboration that you put out to the world and announce with an artist. In my original project, Sarah Lucas was actually someone who I proposed doing a collaboration with. I even did sketches of what we could do…

Did you approach her?

Daniel Roseberry: No, never, but there was definitely a conversation with her in my mind with the original project. I would love to do that. I’d love to collaborate not only with visual artists; doing music together would be almost more interesting, something about visual and non-visual together feels less contrived. There is something more open about the musical process. It is a playground for me where I can create something visual within a space like this. Sometimes I have albums that I remember specifically listening to while creating a collection that are then so inextricably linked. I remember the project I made to be hired for Thom Browne was done in accordance with Björk’s Homogenic. That would be a dream of mine to collaborate with musicians.

‘I like the idea of being able to hide behind the heritage and the weight of something, like Schiaparelli, that existed before me. It’s legitimizing.’

Contentious question: do you believe that what you do is art?

Daniel Roseberry: I think couture can approach art, but for the most part I would say that it’s an applied art.

How do you feel about social media? You have a personal Instagram, but do you fantasise about being able to present a collection where iPhones are banned and the experience remains purely within the moment, held as a memory communicated verbally without an accompanying barrage of imagery? Perhaps even going back to the golden age of illustration?

Daniel Roseberry: I do fantasise, if not every day, then every other day, about getting off all social media. I would love it. I remember when Tom Ford came back for his first collection and there were no photographers and no phones allowed, and I remember Steven Stipelman was there to do illustrations instead. That was an impossible throwback. I’m 36 and I’m the last generation that remembers what it was like to go through high school without any social media. I would gag for the opportunity to present work to an engaged audience, because when I look on the monitor backstage, no one is even looking at the collection, they are looking at their phone screens. It is unreal to me that we have spent hundreds of thousands of euros and hours creating what we would hope would approach art and then the people who are there physically are just watching it through their screens… It’s like going to a movie theatre and watching a movie through your phone screen. It is totally devastating. Whenever I have gone to a show, I make a point never to bring my phone out. It’s not that it is disrespectful, but it’s a major missed opportunity. Lacroix said, ‘I want people leaping’, but no one is going to leap through their phone, like why watch it? You have to really let go to leap. I have a really contentious relationship with the digital world, but at the same time I know there’s no point in fighting it. It’s happening no matter what.

Yet you do enjoy the photographic process these days, shooting your own lookbooks for the last couple of seasons. Do you feel you are the person who is most trusted to represent your own work?

Daniel Roseberry: I know what goes through the minds of people when a designer says, ‘I want to shoot it myself’, because every single person I talked to about it literally rolled their eyes and said, ‘OK, here’s another one.’ I’ve heard the way people talk about other designers’ photographs, but I felt like it was a sort of an extension of the creative process. When we came back from Covid, we did this shoot outside because we wanted to do it without masks, and it was so much fun. I just absolutely loved it. It was going to be me and [stylist] Marie Chaix, whom I see as a partner in crime, especially on those shoot days, and to have to go through a photographer’s vision for a lookbook didn’t seem necessary. For an editorial, yes, it is completely different. Do I think I’m the world’s greatest photographer? Well, no! [Laughs]

How much of yourself have you written into the creative process or is it just so all-consuming that it consumes your whole life? I’m thinking about that first show with you at the centre… Do you have time out from that identity? Can you step aside from your work?

Daniel Roseberry: It’s everything to me. All of me is wrapped up in it, and using of myself, exposing myself felt really urgent in that show. It’s an impulse I have every season that I have to fight a bit because a designer putting himself at the centre can be distracting or just really unwelcome; not many people want to see that. It made sense with that first show because it was an introduction, a coming-out of sorts, but I feel most myself when we are in fittings upstairs at the Place Vendôme. I feel this sort of split personality thing happens when we are creating couture; I literally feel so connected with what I am supposed to be doing. The only other place that I truly feel that way is when I am in Maine, and there is always this sort of fork in the road between the hyper-introverted way and then this extroverted performative way. That is what I love about dressing celebs, because it is as close I will probably come to being on that red carpet.

Do you dream, and if yes are they vivid and visual?

Daniel Roseberry: I rarely remember my dreams and when I do it’s because they are sexual in nature.

I was about to ask you to describe a recent one!

Daniel Roseberry: I had an erotic dream two nights ago, but the person was just laying on top of me, like I just could feel the person’s weight and I woke up in the middle of the dream and they were whispering in my ear. It was a very intense sensual dream…

Do your dreams in any way motivate your work?

Daniel Roseberry: My daydreams are the motivation and that goes back to the Surrealist process. I daydream during walks, on a train or a plane; it’s very EGS, looking out of the window, listening to music. That sort of free association, daydream world, which is 95% of the dreamworld.

This is the wonderful Surrealist idea of disponibilité or availability. How important is storytelling in your work? Do you start with any kind of meta-narrative, like a figure from a movie or someone you’ve found really inspirational? Is it something technical or material, or is it more ephemeral, just a feeling?

Daniel Roseberry: It is more about what I want the emotional payoff to be. It’s not literal. I think sometimes of the muses and the different inspirations that present themselves, but they are all a consequence of how I want people to feel during and after the show, and where I want the house to be placed in their mind, in the echelon of the different houses. It is a very emotional strategy. Sometimes I will write the review that I want to be written about us, months in advance, as a way of setting a goal. I remember doing this first because I read a Tim Blanks review of a Thom Browne show. I love the way Tim reviews, and his work has always been super-inspiring. It became like a mantra for me to sort of chase this – this is what I want people to say about this show – and I write as if I am writing it for Vogue in the third person, then I put it away until after the show. It’s a meta mantra-setting exercise.

I’m intrigued by the passion you have for Hanya Yanagihara and her extraordinary books. Her most recent novel, To Paradise, which I just finished, is dedicated to you. Can you talk a bit about your relationship with her and how and why her work has been so important to you?

Daniel Roseberry: My entire youth up until the age of 23 was a conversation between me and shame, which was like the devil on my back the entire time. Right when I came out, I also started taking prescription Adderall, which I took every day for eight years. It was the hardest thing to quit, quitting smoking was nothing compared to quitting that, because I couldn’t do anything without it. I couldn’t work without it. That really marked my twenties; it was a huge burden for me. Just this sort of hyper self-hating conversation I was having as I was trying to remove myself from the shame of being gay in the Christian world and being a broken heterosexual, or whatever the narrative was. When I read A Little Life, there were moments where I literally slammed the book closed and would audibly yell at Hanya because she was in my head and putting words and actions to the inner workings of my mind and the past experiences that I’d had, and I was so upset with her for that and also for the way that she ended the book. Many of our conversations are debates because for her that book is basically a treatise on the idea that certain people are beyond repair, and that there’s a point at which redemption cannot really access you, and – this is the Christian side to me –

I fundamentally disagree with that; I have to. That book really triggered a flashback to the co-dependent relationships that I had been in. That’s what I said to her, I said that book is bullshit, because the relationship between Jude and Willow is an impossible relationship that you make work – but it’s not real. It’s a complete facade. I have been in those relationships with straight men who bend to be your partner, and it was just such a sham. Co-dependency was a huge thing for me in my relationships. But I still loved every page of that book –

it blew me away.

Do you think her third novel is a response to that idea of redemption?

Daniel Roseberry: I’m only half-way through To Paradise, but I do know that that novel was dedicated to me because it was written during our friendship and during extensive conversations that we were having about each other and the global potential for redemption. So I’m very curious to see how she bends or doesn’t bend to that idea.

There is one quote that struck me in To Paradise, which reads: ‘it’s funny because of all the things I was scared of, I was never scared of the dark, I was never scared of the dark, in the dark everyone was helpless, and knowing that I was just like everyone else, no less, everyone made me feel braver.’ Are you scared of the darkness? Of the unknown or on the contrary, like David in the book, are you reassured and empowered by the knowledge that we can never know ourselves or anything?

Daniel Roseberry: I know that I’m being influenced by my Christian upbringing, but I don’t believe in that at all. I don’t believe that we cannot know ourselves. There is no way we can grasp everything, but I also don’t think that God wants to remain unknowable. That’s the thing – the point is to try and know and to try and excavate, and I think that inside of that there could be redemption. So, no that is not me.

Does Hanya’s dystopian vision of the past and present, and her engagement in this narrative, inform your own way of seeing things in any way? Is potential environmental disaster or a global conflict or pandemic factored into your own design fantasy? Could you call your work political, like the Surrealists? Do you have a manifesto?

Daniel Roseberry: A lot of people ask me what designing clothes for the end of the world looks like, because when I started at Schiaparelli, I said, how do you dress for the end of the world? That was in 2018. I guess you have two options: you can sort of address the reality and embrace it or you can create an imaginary space in which we can all be naive again. The last collection we did was a little sombre, a bit stoic; it was definitely rooted in rigour, which felt comforting, given the times. But the season before that and the season I am working on now are, let’s say, much more like the first 10 minutes of Father of the Bride; I don’t know if you have seen that film. This is the kind of comment that Hanya would want to kill me for, but I remember watching that movie when I was 13 years old. It’s a terrible reference, but it is pre-everything, pre 9/11, pre-Covid; it’s just like this blissful innocence, similar to when I watched the Warhol documentary, with its pre-AIDS world… I find myself running to those periods as a point of reference and when we talk about the Exquisite Corpse and the Frankenstein-ing of different designer’s work, I’m always going towards that sort of time compared to now; those naive periods, where glamour could just be glamour, and there was a freedom to it. I have a hard time knowing how to address the meaninglessness of all of it.

‘My relationship with Paris has been rough. I feel like a stranger in this city. I’ve never spent more time alone than I have in the past three years.’

You were talking before about fantasy and celebrities and of course, you and your designs are no stranger to the red carpet, whether it’s cinema, music, or a presidential inauguration. What is your perspective on this form of performance or power dressing?

Daniel Roseberry: I am so inspired and interested by the idea of fame and celebrity, and the way that human beings can create pop culture. What it does to you as a human being has always been super inspiring for me. Michael Jackson, from the very beginning, became a sort of keynote figure for me because he was extraordinarily shy, but he became a more alive version of himself on stage. I’m always thinking about that whenever we are dressing people. When we dressed Gaga for the inauguration, I was thinking about what it must be like to wake up in the morning. I mean, how do you even sleep the night before? And then you get dressed, you brush your teeth, you go to the bathroom, you have your coffee before you literally perform for the entire world – live.

Balancing those mundane everyday life actions with a global performance.

Daniel Roseberry: I imagine there is something extremely destructive about that as well. We have both been around enough famous people, we know that maintaining your humanity and your connection to what is real is a challenge. I have been around many famous people in the last few years, and I often feel that even if they are asking you questions about yourself, they are just going through the motions because they know it’s what they should be doing. It’s really rare to meet someone who has been able to stay real.

It has been inspiring how your clothes have been worn by such a diverse and amazing community of artists. What have been some of the most satisfying moments for you, when you have felt there was a perfect osmosis of form and figure, of celebrity and humanity, of appearance and being?

Daniel Roseberry: I think that 2021 was so unique because although we didn’t even realise it until 2022, there were a lot of first moments last year, like the first post-Covid moment. We had Gaga at the inauguration and then Bella [Hadid], who was the first red-carpet moment in Cannes. I was particularly proud of Bella because it felt like a really harmonious marriage between something that was approaching art with someone who was purely representing a pop-culture moment in time. For me, it was all so simple. I think that the idea of the lungs was literally to see just her face and those lungs and that was the entire moment. I am really proud of how pure that moment was, and for me it was the moment of last year.

‘With Chanel, Dior or Balenciaga, you don’t get a true personality or a sense of humour like you do with Elsa Schiaparelli. That is her greatest legacy.’

Having worked with the actress Tilda Swinton myself for many years, it is a pleasure to experience a fitting where the star and the designer feel a real frisson of excitement and pleasure at the craftsmanship and vision with which they are engaging. In Tilda’s case, she also feels a real connection with the brand and the house’s historical past. How do you experience these moments? Is it inspiring?

Daniel Roseberry: The first ever movie I saw Tilda in was The Beach, and I remember it very well because her role was hyper-sexual, and I was quite unnerved by it. It wasn’t until I Am Love that she became seared in my mind. Do you remember when she eats the prawns? That scene, I return to that scene, I would say, weekly in my mind. I just love that moment, that hiding in plain sight; it’s one of the most key scenes I have seen in a long time. To be with her in a fitting, and to be working on dressing her and seeing these clothes come to life is electrifying. It is hard to know if the aura, the glow, the inspiration is coming because of the moment or because of the build-up to that moment that I have had for years. It is just so gratifying, and in this particular case, it was the first fitting I had had with a human being for almost two years because of Covid. It was the first time a human being who was not one of the house models had come to try things on. It really felt dreamlike in a way.

Tilda is very specific in her engagement with the world of fashion. She demands an intimacy with her collaborators, which as we know is not always the case. Is Tilda seductive because she wears the clothes in a more ‘real’ way and navigates a real space, rather than the fantasy of a public-performance arena? Do you prefer your clothes to perform, to project, or do you want them to exist in the present?

Daniel Roseberry: The reason why we have had such a diverse clientele on the red carpet is because I think I can do both – and I want to do both. The conversation with Tilda, and the personal connection that we felt when we were dressing her, was indeed the reality of her being and it didn’t feel like a superficial celebrity artifice that she was going to project. You know when you dress a pop star they are looking to project out and hold everything back inside. With Tilda, you feel there is a generosity, like she’s letting you access a true part of herself. That is what makes the magic happen on the red carpet, because she is doing that there as well. That’s how it felt. But for someone else, like an iconic global popstar, that is not what the world really wants from them. Like Gaga, there is a necessary boundary between who they truly are and then what they are giving to the world, which I totally understand.

We can endlessly debate the relative importance, value and impact of clothes that exist on the red carpet with their exquisite unobtainable fantasy as opposed to something that is commercial and accessible. You have been developing the ready-to-wear collection over the past few seasons. How have you been exploring that in relation to couture? Are they like vases communicants – communicating vessels – to use a particularly Surrealist idea, or do you approach the two collections very differently?

Daniel Roseberry: What really connects them is the colour story. As long as the colour stories echo each other, the connection can be made even if the silhouettes are wildly different. Our couture process is really well defined now, and it’s just about fittings, even more fittings with artisans. We had over 20 fittings for the last couture collection. There are things in the couture fittings that we think would be amazing for the ready-to-wear, for which my rule is that these insanely chic people who come for press appointments or private shopping should be able to leave wearing something with their jeans. It needs to be about the ease of something, about the ease of it all. Couture is designed for the most extraordinary and precious moments of your life, whether it’s a wedding, a bat mitzvah, an opening of something or an event that you are hosting. And the ready-to-wear should be for everything else, for all of the other moments.

How has your relationship with Diego Della Valle evolved over these last years, and do you share the same vision for the house?

Daniel Roseberry: Diego has been in love with Schiaparelli and Elsa Schiaparelli for years and years and years, and he acquired Schiaparelli right about the time he acquired Vivier. Diego and I connect first and foremost about the dream of Schiaparelli – he calls it the ‘last great dream in fashion’. It is this sort of untapped or pure uncontaminated house that has not been spoiled in any way and we both really deeply connect on the potential of the house. At the beginning, the relationship was just going through a defining and redefining phase. I think that my aesthetic vision was different to the one he was expecting, and I was not referencing the codes of the house enough. We had to have a come-to-Jesus type meeting about that, and I will never forget it. He kind of explained more explicitly what he needed to see in order to feel good about pouring all this money into the project. I love an assignment and that reckoning was an assignment. Then Covid hit. I had peace and quiet because no one was able to visit for over a year. Diego was not able to come here, even if we could meet up in Italy and we could communicate, but I was largely left to work on my own and I think that what emerged was this vision that’s in accordance with what he wants, too. It’s something hyper-luxurious, but also – and this is important to me – it is also hyper-alternative. When you look at the direction that Chanel and Dior and all of those houses have taken, it is undeniably mainstream. That opens the door for us to do something that feels almost like alternative music, and that is what I would hope we are establishing.

If there were to be a new perfume, what would be the ideal components? I am not asking in a literal sense, the components could be abstract, an emotion.

Daniel Roseberry: For the house to re-engage in a conversation with fragrance, we would need to entirely revisit the way in which Elsa approached perfume. As with everything, she had her own unique way of doing fragrance, and the way she marketed it was completely revolutionary. Some of these more iconic old perfumes no longer resonate with today, but their formulas usually hold the key as to how to move forward. What Schiaparelli’s answer to fragrance would look like today feels very intriguing.

There is a quote from A Little Life about happiness, where Willow says: ‘but what was happiness but an extravagance, an impossible state to maintain. Partly because it was so difficult to articulate.’ What is happiness to you? Are you happy in your creative environment?

Daniel Roseberry: I would say the past six months have been extremely difficult here in Paris, just because I feel so married to the job and so alone in it as well. It’s like a season I guess, and I think that Paris holds something bigger for me to unlock.

I’m sure. Paris is a hard nut to crack on many levels!

Models: Maty Fall, Lawal Badmus.

Casting: Holly Cullen.

Make-up: Chiao-Li Hsu.

Hair: Virginie Moreira.

Nails: Ama Quashie.

Set design: Ibby Njoya.

Production: CLM. Producer: Sydney Marshall.

Retouching: Touch Digital.

Styling assistant: George Pistachio.