Glenn Martens reflects on his season of juggling Y/Project, Diesel and Gaultier Couture.

By Rana Toofanian

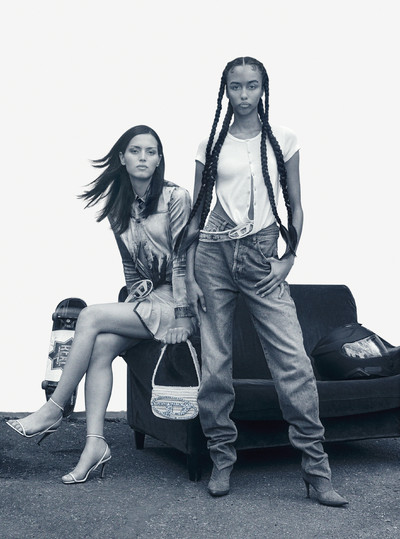

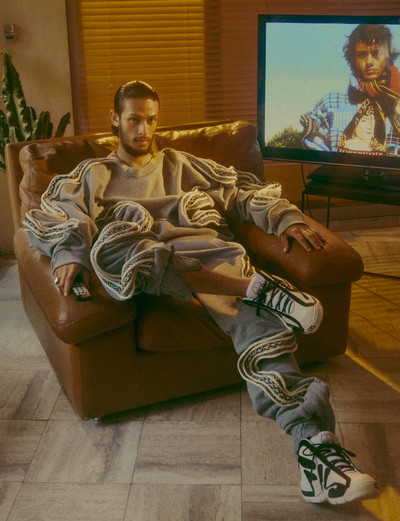

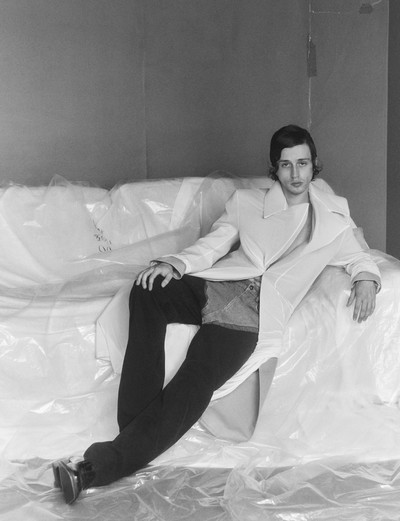

Photographs by Charlotte Wales

Styling by Ursina Gysi

Glenn Martens reflects on his season of juggling Y/Project, Diesel and Gaultier Couture.

Natasha wears Diesel Autumn/Winter 2022

Glenn Martens is avoiding burnout by taking on more jobs. That might seem counterintuitive, but Martens, creative director of Diesel and Y/Project, and the latest couture collaborator at Jean Paul Gaultier, is relishing the opportunity to experiment across such disparate brands. And he’s doing it well. His most recent collections for Diesel and Jean Paul Gaultier were lauded by fashion critics and have made him one of this year’s most talked-about designers.

Born in Bruges, a small, picturesque town in northwest Belgium, fashion design wasn’t even on the horizon until, on a study trip to Antwerp, he happened to visit the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. With no portfolio, he applied to its competitive fashion-design programme. He was accepted, but his first couple of years were spent on the verge of failure until, as he describes it, ‘something clicked’.

Fast forward to 2013, when Martens was named creative director of Y/Project, after the brand’s founder, Yohan Serfaty, had died of cancer. The French designer had established in 2011 Y/Project as a dark and gloomy menswear brand known for sleek, dystopian outerwear, but under Martens’ stewardship it has become better known for bold experimentation and unorthodox design, a space for humorous creativity, expert craftsmanship and unpretentious fashion. This change of direction soon caught the attention of the wider industry, earning Martens a reputation as an innovative thinker with fresh ideas among industry peers and fashion-conscious millennials.

This past year, Martens has been balancing that position with two others, an opportunity afforded only to the very best. At Jean Paul Gaultier – the label where Martens secured his first job out of the Royal Academy – he was asked to create the Spring/Summer 2022 haute-couture collection. Presented in January, it was full of gowns corseted with desiccated bands of tulle and chiffon, and was an undeniable success, in part because Gaultier and Martens share a taste for the unconventional. Martens has injected a similarly anarchic spirit into Diesel, where he was named creative director in October 2020. His debut collection, which showed in Milan earlier this year, was full of shredded dresses, frayed denim and feathered jackets, prompting the New York Times to dub him ‘the first great designer of 2022’.

In other words, Martens is the man of the hour. Following a stellar start to the year, he sat down with System to discuss creative experimentation, the role of celebrity in design, and what it means to move between the niche and the mainstream.

How are you?

Glenn Martens: I’m good! Today we’re in Venice for the opening of the Tom of Finland Foundation exhibition, All Together, which Diesel is supporting. It’s beautiful; Durk Dehner is here and it’s the very first time this work has come out of LA. The LGBTQ+ art on display is from a time when being gay was illegal and all the art pieces are super small because they were doing them in secret. Tom and Durk really changed the perception [of queer communities] for the world; it’s thanks to their activism that people like me can live a life of freedom in Paris, New York and Milan. It is quite emotional. We’re opening the exhibition tonight; it will be a lovely moment.

A brand like Diesel comes with a huge platform. How do you think about your position and the power it holds?

Glenn Martens: When you are creative director of a brand like Diesel, which talks to everyone, not just those who can afford luxury, you really have a voice. With that comes responsibility to help build a better future; we can give a platform to game changers like Tom of Finland.

What access to and awareness of fashion did you have growing up in Bruges?

Glenn Martens: Bruges is a very cute provincial town; it’s known as a sleeping beauty. It used to be a metropolis in the Middle Ages – the equivalent of a Manhattan – but after an economic crisis, Bruges the metropolis died. Today, it has this amazing Gothic architecture and not much else. I was raised in a very traditional family – on my mother’s side, they are all strict military people – so growing up, I wasn’t aware of what was happening in contemporary culture. I lived in this fairy tale of Gothic churches and buildings. Clothes were markers of social status in high school, not creative statements. Back then, the cool kids had Diesel clothes or an O’Neill jacket. I was a bit of a geek, to be honest; I thought I would become an archaeologist or an Egyptologist. My dad is passionate about history, which meant going to museums, castles and palaces to see historical or classical art; he would talk about the art and create stories about every single painting. I became obsessed by certain historical figures, and I would draw all the time. My first connection to fashion came from drawing Marie Antoinette, Caesar and Napoleon. I didn’t know how they looked; it was their costumes that made them wh they are remembered as. I discovered that clothes could create personalities, that clothes have social power. I started to become aware of fashion, not as a craft, but as something to study.

‘Clothes were markers of social status in my high school, not creative statements. Back then, the cool kids had Diesel clothes or an O’Neill jacket.’

How did that take you to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, applying to do a fashion degree?

Glenn Martens: It was a bit of a happy coincidence. I studied Latin and languages in a Catholic college, but when I was 18, I realized I wasn’t made to study Classics at university. I was hyperactive, and I thought something artistic might suit me better, but I didn’t know what, so I went into interior design. The course took me on a trip to Antwerp, and I think that was the year the Royal Academy’s fashion department had just reopened. The building had been renovated by a very famous Belgian architect, so naturally we had to visit it. I remember thinking it was a gorgeous place in which to spend part of my life, so when I graduated from interior design, I was like, OK, let’s try to do something else. I was 21 and I didn’t really think it through. At the entrance exams, I suddenly realized the reputation of the course: there are about 400 kids trying to get in every year, and the Academy only accepts 80. My portfolio consisted of chairs and kitchens – nothing to do with fashion –

but I was accepted. So I jumped in, very unprepared. It was a culture shock, totally eye-opening. For the first two years I was on the verge of failing all the time, but then something clicked and, somehow, I managed to work it out.

You were the underdog back then.

Glenn Martens: During the four years you are studying, there is a lot of pressure because most people in the class ultimately fail. Just 14 of us graduated in my year, and that was a big year; normally, there are only 8 – from 80 to 8. The teachers never tell you what to do, they just say ‘do it again’. That provokes constant introspection: why, why, why? They force you to question yourself all the time until you understand who you are and where you want to be. In a way, it is a school focused on forming creative directors. But it worked out and it was a really beautiful time. The Academy is great; everybody is so flamboyant and eccentric. It’s like being in a film every day. You work your ass off, which is good preparation for when you enter the industry! Yet everything was a cloud of happiness, joy and extravaganza.

How did you end up working for Jean Paul Gaultier after graduating?

Glenn Martens: It was another lucky coincidence. There was a magazine titled Encens and its editor-in-chief, Samuel Drira, was on a jury at the Academy. He thought my work was really great and he connected me to the head designer of the men’s department and the women’s pre-collection, who in those days was Gilles Rosier. I was given a job straight away. It was very junior – I was the assistant of the assistant – but that’s how I ended up in Paris with a salary and a 10m² studio apartment. It was lucky I had a job because my parents would never have been able to afford to finance me doing an internship abroad. In those days, Gaultier was not the brand I had been dreaming of; I was drawn to Nicolas GhesquiПre, Balenciaga, and Phoebe Philo. Then I arrive, and I see the heritage of the house and how Jean Paul works. It was an amazing start to my career.

Gaultier is a well-known inventor and a disruptor. How important are originality and invention to you?

Glenn Martens: My way of speaking is experimentation; it’s about finding new things, and I think Jean Paul also has that. He was the first person to really work on street casting. He was one of the first people to bring streetwear to elevated garments, denim to luxury. Once you understand what he did and how he opened the doors for other designers, then you can only respect and look up to him.

You touched earlier on the idea of creating clothes as a means of self-expression and communicating ideas. You are often described as a ‘conceptual designer’, like Rei Kawakubo or Hussein Chalayan. How do you feel about that label? And, more broadly, what do you feel the function of fashion is?

Glenn Martens: Those are two different questions. I am definitely a conceptual designer. I have to have a concept; the silhouettes and the garments come afterwards, which is quite a Belgian way of thinking. Even Dries Van Noten, who is more focused on beauty and colours, has said that his colourways come from a concept, and then he develops the prints and graphics. To your second question, I think fashion is about making people feel strong about who they are and how they want to be perceived. Clothes carry power, which is why fashion is so exciting. The great thing about fashion is that it has many different purposes depending on your market, depending on the brand you are designing for.

You are in the position of being one of the few people who designs for multiple brands. You have a big workload, multiplied by three. Which part of being a designer do you enjoy the most?

Glenn Martens: I am very blessed to work in an industry that is also my passion, where I don’t actually feel that work is work. I wish more people could live like that. When you are younger, you are hungry to express yourself; you really want to scream out very loud. I don’t have that need any more; I think I have screamed loud enough that people respect me for my creativity. Now I feel extremely pleased when I see somebody having a lovely day in a basic, sustainable Diesel denim. It is beautiful to think that they are living their life, walking around the Venice Biennale or wherever, and this brand is part of it. And I am even more proud because it is sustainable. When you are a director and you work with different teams, you also become a bit of a psychologist; it’s great to see people grow. Honestly, there is not one moment that I truly loathe what I do.

Being at the helm of a brand like Diesel comes with a lot of media responsibilities and attention. There’s also a lot of pressure on designers now to exist as personalities and be visible. Jean Paul Gaultier mastered this.

Glenn Martens: To be honest, I work so much that I don’t have any spare time to be a celebrity, but if it happens, then, cool. I was in SoHo in New York earlier this year and maybe four or five times, people stopped me in the street. Of course, it is satisfying that people love your work and are interested in who you are and what you do, but I try to be outside of cities as much as possible in my free time. I need my nature walks, I need to visit castles and churches, because my brain needs to shut off to refresh.

‘I was given a job straight away at Gaultier. I was the assistant of the assistant, but that’s how I ended up in Paris with a salary and a 10m² apartment.’

What other things did you learn from being around Gaultier?

Glenn Martens: The most important thing that I learned from Jean Paul is the value of enjoying things outside work. Jean Paul Gaultier enjoys life so much; he is like the French clichО of joie de vivre. Every day was fun with him, and you felt that in the company, too. A lot of people I knew did internships in other Parisian houses and the pressure was unbearable, the culture was toxic, as it can be in fashion. Gaultier taught me: why would I ever go into such an intense industry if I cannot make it fun for me and the people I work with? I have to be a bit bossier now as a creative director, but it is not a toxic environment. I cannot operate any other way.

Some could say you have moved from being niche, beloved and celebrated by industry insiders for your work at Y/Project to being in the mainstream cultural consciousness at Diesel, with a brand that has massive reach.

Glenn Martens: Y/Project was really about embracing uniqueness; it was not about classic beauty or the hype of streetwear, which was intense when I first started building up Y/Project. Huge brands were copying the identities of other brands, and no one seemed to care. It was connected to social media, when everyone started consuming visuals and became lazier and less willing to dig into things. I really wanted to push what I believed fashion was and what I wanted it to be. Because of that, a lot of the collections I brought onto the runway were maybe difficult for outsiders to digest. I really wanted to reflect on what is acceptable and what is not acceptable, on how we can do things differently. That made Y/Project more niche and it is still like that, except finally, people understand that this is the point of the brand. We are not the opposite of streetwear or logomania; we just want to celebrate independence. I have noticed a lot of people saying this, and that’s something I am actually very proud of. Rick Owens and Margiela each has his own language. Nicolas GhesquiПre, Phoebe Philo, Raf Simons, Dries Van Noten: they have their own languages and they are all designers who I really respect, regardless of their aesthetic. I am not saying that I am as good as them, just that I am proud that we have managed to establish our unique identity in this saturated industry. That doesn’t mean that I can’t do other things. I focused on beautiful silhouettes with Jean Paul Gaultier, for example, while the focus for Diesel is more social; it’s about being part of people’s everyday lives. Putting a logo sweatshirt on Y/Project’s catwalk would have been like selling my soul, but I can do that at Diesel: create great sweaters with great logos and sell them at a democratic price, in a way that respects the customer and the industry and the environment. It is very important to be connected to the brand you are working for, to understand why it is there and not to get bullied into doing other things.

In order to stay afloat,many brands extend themselves into other categories that aren’t necessarily them. Logomania was already a part of the Diesel identity, so I suppose you can approach it there with a fresh perspective.

Glenn Martens: People want to wear a sweater with a Diesel logo on it. The people I talk to are not always obsessed by fashion; they are more interested in the environment and looking great. I have done logos at Y/Project, but it was never just a logo, it was a whole concept, a whole graphic identity with crazy, distressed embroideries. I have belts with the Y/Project logo on them where the Y is the buckle. There is always a concept behind it. At Diesel, the basic logo jerseys will, starting in June, all be made from organic cotton, including the prints and inside the stores we will have QR codes explaining the sustainability approach behind each garment. I would never just make a sweater with a logo; there needs to be something more and that is where the power of Diesel lies: in diffusing these messages about sustainability and raising awareness of these issues.

You’ve mentioned how important sustainability is at Diesel. Does being at a big brand allow you to test techniques you can then apply elsewhere?

Glenn Martens: Y/Project is always the most experimental. It is where I test things and then I might bring them to Diesel

It’s the other way around, then?

Glenn Martens: That’s how I’ve done it. It’s not so easy to have a sustainable approach with big brands because of the price point. The moment you use organic or certified cotton and incorporate different treatments to your denims, it becomes more expensive. It’s very difficult to make people worldwide – the millions of customers we have – understand that the same quality of denim that they bought two years ago suddenly went up in price by џ20. Since the 1990s, we have all been raised to buy џ10 T-shirts from big mainstream brands, and you can still buy a sweatshirt for џ15, but there is no way that there is no blood attached to it. There is always blood attached to something so cheap. Imagine the process: growing and picking the cotton, dyeing it, stitching it – there are so many steps before the sweatshirt is sold for џ15. But we have been raised to think it’s OK. I don’t have that issue with Y/Project because it is a luxury brand, so customers won’t complain about paying џ20 more. What I do at Y/Project is insist on certain ideas; every season, we’ve tried to reinvent the brand. During confinement, for example, we developed the Evergreen line, which is not allowed to go into sales or be out of stock; a big part of Y/Project’s turnover is based on those pieces. They are all quite experimental, but they have a bigger audience just because we insist on them. The Evergreen project at Y/Project prepared me to experiment with the Denim Library and the essential jerseys upon my arrival at Diesel – they also can never go into sales – and now that works really well.

‘Putting logo sweatshirts on Y/Project’s catwalk would have been like selling my soul, but I can do that at Diesel and sell them at a democratic price.’

You sound really happy. But it has been a weird, and I imagine quite stressful, two years, especially if you are working across multiple businesses. Are you feeling optimistic about the future?

Glenn Martens: I don’t feel optimistic about the future, in a global sense. My grandfather turned 98 on 9 April 2022. He spent the first years of his adult life in the trenches fighting the Nazis and saw his best friends die. Now, he turns on the television and sees the same sort of war happening in Europe. It is disgusting. Humanity has this fantastic power to forget. That’s also why I insisted on this exhibition for Tom of Finland. Activists and artists fought so hard to make life possible for people like me, a gay man in Europe, and I really live my life to the fullest thanks to those who fought and were persecuted. I am sure this will be lost again, and that is why I am not optimistic. Though personally, and in terms of my work, I am quite optimistic, because I have an amazing team. Also, Y/Project, Diesel and Jean Paul Gaultier are all alternatives within the industry, all independent and unique. In Paris, I am loved because I don’t think other designers feel that I am competing with them. In that way, I am very blessed. All three companies are quite ironic and don’t take themselves too seriously; they are all based on celebration – which is a nice way to live.

Models: Natasha Poly at Women Management, Lorenzo, Redouane.

Hair: Laurent Philippon at Bryant Artists.

Make-up: Masae Ito at M+A Paris.

Casting: Ben Grimes.

Nails: Chloé Desmarchelier.

Set design: Nara Lee.

Retouching: Meredith Motley.

Lighting assistants: Virgile Biechy, Alexandre Sallé de Chou, Yves Mourtada.

Digital operator: Henri Coutant.

Producers: Lisa Stanbridge and Raine Stephenson at M+A London.

Stylist assistant: Michèle Lian, Livia Dominica.

Hair assistant: Michael Thanh Bui.

Set-design assistant: Ettore Crobu.