Why everyone knows Nigo.

By Fraser Cooke

Photographs by Norbert Schoerner

Why everyone knows Nigo.

On 23 January 2022 in Paris, Tomoaki Nagao, better known as Nigo, unveiled his debut collection for Kenzo. Front row at the show was a who’s who of musicians and cultural figures, most of whom also collaborated on the designer’s recently released album, I Know NIGO!, including Kanye West; Tyler, the Creator; Pusha T; A$AP Rocky, and Nigo’s long-time business partner, collaborative co-conspirator and muse, Pharrell Williams, who co-produced much of the album. The show they and the rest of the packed audience saw was Nigo’s reworked vision for Kenzo, one that remixed his and the house’s Japanese heritage with his long-time love of Americana. Hickory-striped overalls; Kenzo-emblazoned varsity jackets; Industrial Revolution-inspired mechanics jackets; hippie-patterned ‘flower power’ denim: all in a historically appropriate colour-coded homage to the house’s late founder, Kenzo Takada. Nigo’s other nod to the man who brought Japanese fashion to Paris in the 1960s was the location: the shopping arcade Galerie Vivienne, where Takada opened his first Henri Rousseau-inspired boutique, Jungle Jap, in 1970, which in a serendipitous coincidence was also the year Nigo was born.

In 1993, LVMH paid $80 million for Kenzo Takada’s company, which by then included mens-, womens- and childrenswear, as well as perfumes and homeware. That same year, Nigo opened his first store, Nowhere – in an unassuming corner of Harajuku, in partnership with Jun Takahashi of Undercover fame – which launched what would become his multi-hyphenate empire, from A Bathing Ape, Billionaire Boys Club, and Human Made, to a huge catalogue of collaborations. A recent example are collections of clothes and accessories designed with Virgil Abloh for Louis Vuitton, which perfectly encapsulated Nigo’s unique eye for blending high and low, Japan and the West, luxury values and hypewear collectability. With that proven track record, Nigo was a natural choice to take on Takada’s legacy and company.

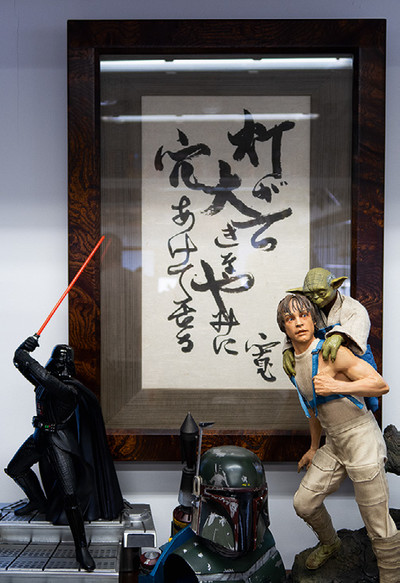

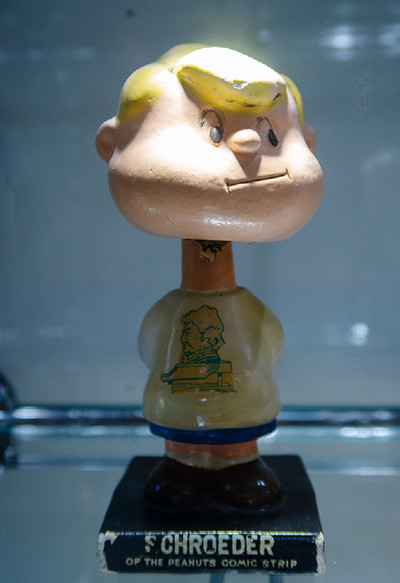

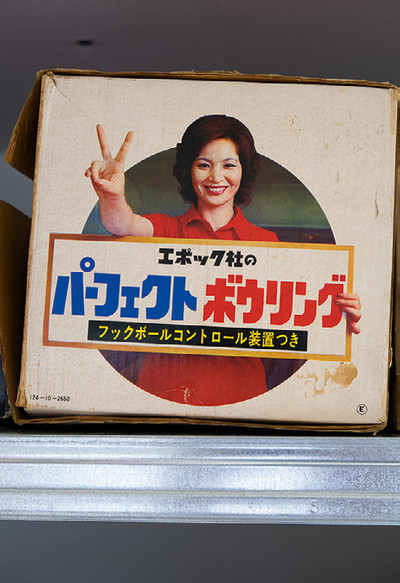

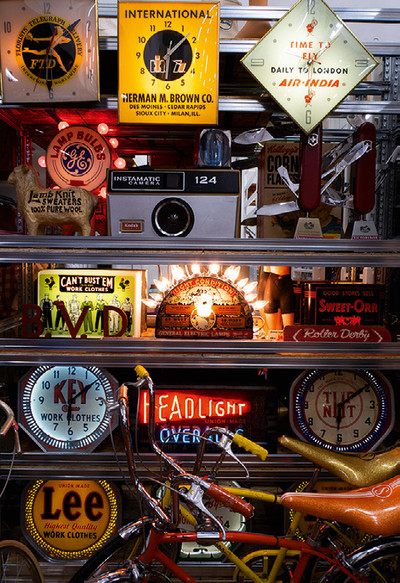

For System, photographer Norbert Schoerner was given access to Nigo’s Tokyo design and archival space, as well as the one-man pottery atelier that’s perched on top of his studio, while Nike’s senior special projects manager – and leading authority on collab culture – Fraser Cooke sat down with Nigo to discuss the complex and ever-evolving rapport between Western culture and Japanese tradition.

An easy one to start with: when you were growing up in Japan, what were your earliest memories of the fashion or arts scenes, those moments that first got you interested?

Nigo: It was in my first year of junior high school. I liked the Japanese idol group the Checkers. They were a 1980s pop group and part of the whole rockabilly revival here. The thing is, I was as much attracted to their visual style as I was their actual music. They were featured heavily in the Japanese magazine Olive, which is like the sister publication of Popeye magazine – not actually Popeye’s wife in this context. I initially bought the magazine because it featured The Checkers, but then I became increasingly drawn to the magazine’s fashion content.

So the band was like a conduit that opened up to other stuff.

Nigo: Exactly. It was the other articles in the magazine with information about things like zakkaya [miscellaneous goods] shops in Tokyo and the kind of items they were selling.

Did you grow up outside of Tokyo?

Nigo: Yes, in Maebashi, Gunma Prefecture. The zakkaya stores in Tokyo were selling interesting stuff and that’s what drew me in and captured my attention. It made me want to go discover the city for myself.

Nigo shows Fraser a copy of a magazine from the time and an image of a couple in layered tartan clothing.

The issue looks cool.

Nigo: It was cooler than it is now; it was experimental.

Yeah, it seems more original somehow. It is quite Comme des Garçons…

Nigo: This was in the middle of the ‘DC’ boom in 1984.

That is a good reference point, because the 1980s was a melting pot of creativity in Japan. When you look at fashion, there was Kenzo, Issey Miyake, Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto. Did you find those designers interesting at the time? I mean, obviously you’re at Kenzo now.

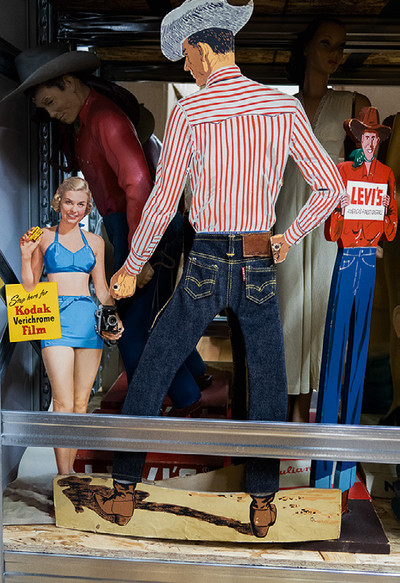

Nigo: There were so many popular brands out there, but the ‘character’ part of DC kind of disappeared, and lots of popular brands like Persons or Pink House didn’t make it overseas. Most people outside of Japan don’t know about them as they never made it internationally. Back then, I couldn’t afford too much, but I spent a lot of time looking and checking everything out. It’s not like now; there was no online. Instead, there were boutiques everywhere, even in small cities, and I’d visit them a lot. I was influenced by the kind of 1950s rocker fashion that the Checkers wore; I loved it. Basically, at that time I was wearing Levi’s 501 and Adidas T-shirts, an MA-1 flight jacket, and clothes from Hollywood Ranch Market, you know, amerikaji [American casual style] stuff.

That was when hip-hop really started to come through…

Nigo: It wasn’t happening in Japan at that stage. [Run-D.M.C.’s] Raising Hell was probably the first big hip-hop album for me. That was probably 1986, 1987…

That makes sense because you are a bit younger than me. When did you first move to Tokyo to live? You went to Bunka Fashion College, right? Some of your contemporaries seemed to be into punk, like Jonio [Jun Takahashi] or Hiroshi [Fujiwara], but I don’t get the feeling that the whole punk thing was so strong for you.

Nigo: I know quite a lot about punk, but the fashion… [he implies he didn’t dress like a punk]. I was a regular at [punk club night] London Nite, but mostly to support my friends. Something interesting about Tokyo is that people aren’t defined or limited by the genre that they’re into. So you can be into hip-hop or punk and still mix; it doesn’t matter. That’s really interesting.

I think that was happening right at the beginning in London and New York. It was definitely a mix of those people.

Nigo: It is mostly London and New York culture that were the influences, with hip-hop and so on.

I guess a good example from the UK would be Big Audio Dynamite: ex-Clash members, with a sort of hip-hop. That was around 1986, I guess, and that had the same mix.

Nigo: Wow. Was that as early as 1986? It’s weird. That far back in my memory is not very clear.

‘I hated Japanese culture! I thought overseas stuff was much cooler. I’d refuse to live in apartments with traditional rooms and their tatami mats.’

I heard that you were studying more to be a stylist than a fashion designer at Bunka College. Is that right?

Nigo: I did the fashion editorial course, but I also did the general courses. We had to do a bit of pattern cutting, make some clothes, do some photography, and we were taught a bit about the business side of fashion. We did some graphic design, too, specifically for editorial work.

What made you pick that course? Did you want to work in magazines?

Nigo: I was always really interested in magazines, and in fashion, but not from the perspective of actual fashion design. I wanted to buy fashion, but I wanted to work in magazines.

Did you have an intention to do things that were deliberately Japanese within your work or has that not been part of your thought process?

Nigo: No. I hated Japanese culture! I thought overseas stuff was much cooler. For example, when I was younger and renting apartments, most of the rooms in them would be washitsu or traditional rooms with tatami mats, and I would just refuse to live there. I really hated it. I wanted to live somewhere with Western flooring.

It’s often assumed by people outside of Japan that there is a strong intention to reflect or embody typical Japanese elements in design work by creators from here. Yet I’ve often found that many Japanese designers actively avoid that culture and aesthetic. They just want to be seen as designers, not designers defined by where they’re from…

Nigo: Well, over time – and it’s taken a long time – I have actually grown to appreciate Japanese culture. The Japanese details I used in the first Kenzo show got a good response and I’m really into the pottery that I’ve been doing recently as a hobby.

I can see that it’s grown over the years. It’s kind of normal to push back against all that when you’re younger.

Nigo: It was quite a big deal because I was so against it, but you’re right, it’s an aging-process thing. I recently met up with Jonio [Jun Takahashi]; we hadn’t spoken about Japanese culture for a long time, but we found we were both really into it now.

When I came to your office with him last year, you were both looking at an auction of Japanese antiques. Sometimes it takes a long time to appreciate where you come from. How long after college was it before you started making clothing? Was the Nowhere store period with Jonio straight after college?

Nigo: When I moved to Tokyo I was already a fan of Hiroshi [Fujiwara] and Kan [Takagi], and I loved the subculture around those guys. I met Jonio when I first got to Bunka and he introduced me to a bunch of people in Tokyo, including Hiroshi. He was looking for an assistant at the time, so I started working with him while I was still at college. I did that for about three years, gradually going less and less to school. Working with Hiroshi was such an amazing experience. I learned so much from him – just his way of working. In Japanese terms, the relationship is like a master-student situation, but Hiroshi would treat me like I was one of his friends, and that was very different to how things normally work in Japan. It was so much fun. I didn’t think of it as work, but it wasn’t play either. We DJed at local venues around Japan, and I learned about music, culture, everything.

When did you start developing your own style, creating your own products?

Nigo: I was doing styling at about the same time I got a part-time job as a writer for Popeye. I’d do two pages each issue, introducing new products to the readers. After that, someone introduced me to Hot Dog Press. By then, Jonio and I were really close, and Hitomi Okawa, the [older and established] designer of Milk, really looked out for us. She thought we were really interesting, and called the editor-in-chief of Takarajima and got us a monthly column together [called ‘Last Orgy 2’]. At that time Jonio was selling Undercover in Milk.

It’s interesting that there is a link to Milk. Hiroshi was also linked to it. There are also ties to the Gothic and Lolita scene, even if it’s aesthetically different.

Nigo: I think Milk was a bit more punk compared to what came after it. But there are common roots; they were all connected.

‘Back then, high fashion used to be pretty uncool; it was just not that cool to be only into fashion. Now everyone wants to be a fashion designer!’

Can you remember when you decided to start making clothes? Didn’t the opening of Nowhere happen a bit later? Was that when you began to make actual product before?

Nigo: It was provoked when Milk decided to stop selling Undercover. One reason was the CEO of the store – who was Hitomi’s mother – decided to stop selling other brands in the store, and only sell Milk. So we began thinking about what to do and thought we could try to set up our own shop where we could sell Undercover. So, on 1 April 1993, we opened the shop and published a column in Takarajima announcing it. We had a lot of fans who knew us from doing the column and they would come to the shop, so our sales were quite good. Still, the major players in the mainstream fashion world were pretty cold towards us.

Was starting to make clothes yourself about filling a gap in the market or was it more like self-expression? I would imagine that Stüssy and other US labels were influential at that point.

Nigo: At this point, my full-time job was styling, and my part of the shop was all about the stuff that I’d been selecting: sneakers, varsity jackets, second-hand stuff. I’d go on buying trips to the US to buy stuff that you couldn’t get in Japan. Just stuff I thought was cool. This was in college towns, like Boston and so on. It was more from an editorial perspective than a fashion perspective at this point. But I soon became too busy to keep going on these buying trips, and it was starting to stress me out. Jonio saw how impossible it was becoming for me because I was getting increasingly busy as a stylist, and so he was like, ‘Why don’t you just start making your own clothes?’ And that was the start of it all.

Was it the fact that you already had an audience that made the clothing pretty successful right from the beginning?

Nigo: Yes. The store was busy from the start.

You’re known for being interested in the roots and the most authentic work from any given scene – both as a stylist and also a huge collector. Would you say artistic interpretations of what you love to collect and reimagine is a component of your creative practice? For example, some of the collaborations and collections for Human Made seemed inspired by Americana and denim culture, like the Levi’s, and George Cox brothel creepers, but you then created your own versions. A lot of those Bape items had that basis, but with extra layers applied.

Nigo: There is a need to understand the roots of what you’re interested in, and if you are really interested in something, you want to go as far as you can. Also, and I think this is really important, what probably didn’t exist very much until Bape, was the use of a platform to support other artists. We call that collaboration now, but in a way that didn’t really exist until the time around Bape. One of the most important things about Bape was that it expanded the repertoire in all areas.

You got a lot of people to work with you. It’s important to note that that changed the whole paradigm; Bape expanded the language of streetwear.

Nigo: The difference is something in my character. Compared to everyone else around me on the scene at the time, who was just wanting to make some fly shit, I really had a vision for a proper brand. I’d been influenced by the DC brands when I was growing up – Yohji, Comme, Issey, and Kenzo – so I wanted to make a proper brand for myself. A lot of other people in the streetwear scene were making T-shirts, but they didn’t really have any real plan or vision. I wanted to do it properly, so I immediately started doing exhibitions, and tried to present Bape as a serious brand that was more than just T-shirts. That’s been my approach from the beginning; I really wanted to do it all properly.

That is very clear in the way you work.

Nigo: That has been how I’ve worked since the beginning.

The blueprint really started with what you did with Bathing Ape, and continues with what you’re doing now.

Nigo: The agenda was really set by Bathing Ape. What was interesting about it was the product range and the way that it was all sold. It was like a complete picture. It’s not like any of this was planned out in advance; everything just comes from my choices and the decisions I made. Like when I opened the first Bape store in 1997: until then I had always asked my friends to do the interiors, never really using professionals, but then because I wanted to do things properly, I brought in Masamichi Katayama, who was an architect, to come on board. I remember he told me that normal retailers always had measurements and stipulations, like how many shelves they would want, but I told him he could do whatever he thought was best. He thought that was incredible. I was an amateur, shaping and deciding everything as I went along.

The store’s success triggered a broader, international appreciation of the brand, which led to the other stores in London and the US. Had you always wanted to do that or was it just a natural part of the brand’s momentum?

Nigo: Opening stores in New York and London was always the aim. The first shop was Hong Kong, but around that time, there was no culture or scene there, so we closed it and reopened it three years later. That time there were 2,000 people queueing up on opening day. So in those three years, the street scene in Hong Kong had exploded.

All this stuff is what we could call streetwear, and it’s in a very different place to what we might consider high fashion. Jumping forward, you’re now working with Kenzo, a high-fashion brand, in part because this stuff has been assimilated into the mainstream. Until Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton, the two worlds felt very separate. That’s when it started to gravitate into that world. What did you used to think about high fashion? Was there a sense of ‘I am different to that’?

Nigo: I’ve always been attracted to luxury brands like LV, and wanted to buy into them, but as you say, until Marc Jacobs arrived the two worlds had never been linked. What I had done remained pretty much invisible to the people in high fashion.

Under Virgil, who you worked with, Vuitton started to do actual skate stuff, with people like Lucien Clarke, proving that the amalgamation of all these worlds you’ve been involved in is almost complete. Is that a good thing?

Nigo: Things have changed and we’ve entered a new era. What was once a real subculture has become part of the global mainstream. You know, rather than what Virgil did at Louis Vuitton, what mattered was that LV hired him as creative director in the first place. That to me was the biggest signal that something had changed in the culture. Virgil was doing what you naturally do as a creative director, but the fact they chose him to head Vuitton – following on from Marc and Kim – that represented a huge change.

‘A lot of other people in the streetwear scene were making T-shirts, but they didn’t really have any real plan or vision. I wanted to do it properly.’

Let’s talk about Kenzo. What was most exciting to you about the job? Did you like Kenzo growing up? Are there elements of Mr Kenzo’s work you find relevant to your work for the brand?

Nigo: It wasn’t something I really had to think about – I just knew I wanted to do it. The factors that led me to taking the role are linked to my own experience of making clothes, of founding brands, of being someone who is mostly in Japan but who understands how things work in the UK and the US, even though I should say the system in Paris is very different. I had had the experience of LV with Virgil, when there was less pressure on me personally, and I found the process really interesting. That made me realize that the opportunity at Kenzo could work. Of course, there was the fact that it was Kenzo – that made a lot of sense to me. He was such a legend: the guy who introduced Japanese fashion to Paris, getting on the boat in the 1960s and arriving on his own and making it. And I had got to the stage where I was like, ‘OK, Human Made is successful and continuing to grow’, and I felt it would be nice to take on a new challenge. The opportunity at Kenzo felt really exciting and I had a new kind of vision for what I wanted to do. Because Kenzo was started by a Japanese designer, I think I found it easier to assimilate and engage with things, even though I never met Mr Kenzo himself. I was actually never particularly interested in Paris fashion; it always seemed quite distant. It’s an area that I still don’t understand that well, so it will be challenging, but I’m constantly learning.

Is there anything on your creative bucket list right now?

Nigo: My ambition is always to do things I haven’t done before, especially if they’re connected to lifestyle. Like, I’ve never done cars, and there was talk at one stage about doing hotels. But those interesting jobs don’t seem to come my way at the moment!

That will change! It seems to be that your work and your personal interests are just completely intertwined, right?

Nigo: Well, I just turn my hobbies into work.

‘What didn’t exist very much until Bape was the use of a platform to support other artists. We all call that collaboration now.’

Is there other stuff you do to escape?

Nigo: I like sailing and pottery, and I do wonder how long I will be doing fashion for. In the olden days, people died when they were 50, and to be able to think of something completely new at that age is quite a feat. My generation and Virgil’s generation are totally different; mine was more rooted in the real, authentic world, whereas Virgil’s approach was partly in the virtual world. And with the one after that, I think we’ll lose the real even more to the virtual. Fashion will continue to go that way. There’s a lot of hype around that at the moment, so with Kenzo I’m trying to make things more rooted in the ‘real’. There’s certainly a lot to think about at my age. I can’t draw or paint, but I can make pottery, and I’m always interested in selling the things I make. That’s my hobby becoming my job again, but it’s something I can do at my own rhythm at least. [Laughs]

The homeware line is the future! Last question: music has played such a big role in your work and life. You’ve just released an album for which you used your creative-director skills to pull different artists together. Will you pursue being a recording artist?

Nigo: Yes, I want to keep going in that direction. I feel that you can’t understand fashion without understanding music, because without it you wouldn’t know where to look in fashion.

It goes back to the band you were talking about at the beginning, the Checkers. Usually fashion is the expression of an allegiance to something else, and for so many people that starts with music.

Nigo: Back then, high fashion used to be pretty uncool; it was just not that cool to be only into fashion. Now everyone wants to be a fashion designer – it’s really strange!