CEO Pietro Beccari on his mission to make Dior more, more, more.

By Jonathan Wingfield

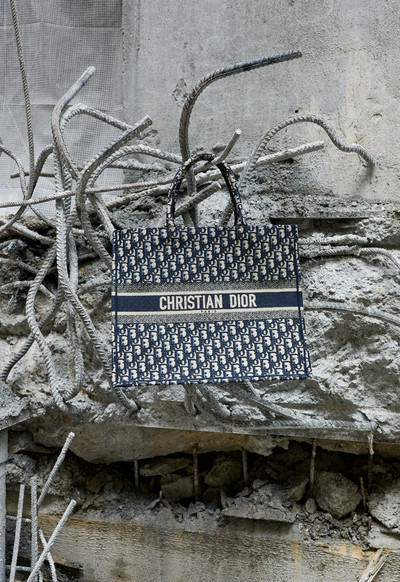

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Creative partner, Dovile Drizyte

CEO Pietro Beccari on his mission to make Dior more, more, more.

‘It had to be 30 Montaigne,’ Christian Dior wrote in his memoirs about the hôtel particulier in Paris’s eighth arrondissement. ‘I would set up here or nowhere else.’ So, on 16 December 1946, with Paris still recovering from wartime hardship, the designer opened his label in the townhouse, elegantly renovated with pearl-grey walls, multiple chandeliers, and, as he wrote, a ‘flood of small palms’. Just two months later, the clothes that revolutionized post-war fashion would emerge from 30 Montaigne’s three ateliers – two flou for soft fabrics and one tailleur for suits – when Dior showed his New Look.

Over 75 years later, Dior’s 30 Montaigne has undergone another renovation. This one is the dream of Pietro Beccari, who joined the house as CEO from Fendi in 2018. Beccari is known for his ability to marry audacious marketing-led ideas with grounded business decisions – in the last two years Dior has seen revenues nearly double – but the crowning achievement of his ambitious vision is the total transformation of the building so beloved by Christian Dior. Opened in March 2022 – ‘only four months late’ despite Covid, Beccari says proudly – the project can be seen as a confident bet on the continuing importance of ‘experiential retail’ in an era of booming e-commerce and social-media virality. In the gargantuan 30 Montaigne boutique, menswear and womenswear have a wing each, while homeware, jewellery, shoes, and beauty each has a dedicated space. The building also houses the Monsieur Dior restaurant and a Dior café, which sells a cake named after the designer himself. There’s even a private penthouse suite for VIP customers, offering 24-hour access to the store, personal shoppers, and chefs.

Then, there’s La Galerie Dior, a spectacular 2,000-square-metre constantly evolving exhibition space that explores Christian Dior’s savvy business mind and pioneering fashion vision, and how that has been interpreted by his six womenswear successors: Yves Saint Laurent, Marc Bohan, Gianfranco Ferré, John Galliano, Raf Simons, and Maria Grazia Chiuri. The gallery’s sheer grandeur, splendour and size has already made it a landmark on the Parisian tourist trail.

Beccari recently took System for a stroll through 30 Montaigne where he discussed overseeing the project’s construction during lockdown, his first ever meeting with Bernard Arnault, and what it means to ‘dream Dior’. Meanwhile, photographer Juergen Teller shot a portfolio of pictures that captures the space both during construction and upon completion.

Jonathan Wingfield: Was the complete renovation and entire rebirth of 30 Montaigne already underway when you became CEO of Dior in 2018 or did you initiate the project?

Pietro Beccari: I initiated it. Construction started very soon after I arrived at Dior. When you take over a brand, you have 100 days to get your best ideas into place, and this one came pretty much immediately. The most difficult part was telling Monsieur Arnault that it would mean closing Dior’s number-one best-performing store in the world; moving the haute-couture ateliers and the haute-couture salon, which have been here since 1947; and the offices that housed 450 team members, without actually knowing where I was going to relocate them. Sometimes you have to decide without too much calculation, and believe in your gut instinct. I went to see Monsieur Arnault and I found in front of me not the man that everyone knows – a finance guy, and a super-smart mathematician – but rather his version of Erasmus. He held any craziness inside and said, ‘Let’s just do it!’ He became my partner in crime. Of course, it was months and months of preparation: we had to design the temporary store and find an alternative location, which was the Champs-Élysées; we had to start designing here, and request all the construction permits. Ultimately, we had to implement the entire project in only two and a half years. The building is 13,600 square metres and this was all done during the Covid pandemic, so we did something astonishing in a very short time.

What prompted your plans in those first 100 days?

You try to make a difference and you try to add your stone to the building. Dior was and is already a fantastic brand, so I started wondering how I could do more. This location seemed so important, its history, the fact we are at the heart of where everything started. I had this intuition that it could be the chance to do something that had never been done before. I wanted to create a paradise for the senses, a lunar park of experiences, something never seen before. I thought that would really make the difference for Dior, and looking at the first results I am comforted that it does.

‘The most difficult part was telling Monsieur Arnault that it would mean closing Dior’s number-one best-performing store in the world.’

When conceptualizing the project, which came first, the idea of upgrading and expanding the store or introducing the museum?

Both together. Just doing a beautiful new store? So what. To create this ensemble, that was the idea – an idea that came to me in the room where Monsieur Dior had started dressing the mannequins. It had become a stockroom where everybody would throw things when they did not know where else to put them. So they showed it to me and said, ‘Here is where everything started.’ Something clicked and I said, ‘What the hell, no one has ever seen this, and no one will ever have the chance to see it, because now it is just a cabinet where things get put. Maybe we should do something, open the wall and link it to the project of the new store.’ When I arrived at Dior, there was already a project underway to put the Dior Man store back where it used to be, on Rue Francois 1er. I remember the day I went down to the people in that department, and I said, ‘Hello guys, put your hammers down, we are going to change everything. We aren’t going to do it like this, but like that!’ Then the whole thing started.

You mentioned that much of the project was constructed during the pandemic. To what extent did this affect both the project and Dior’s growth in broader terms?

Firstly, the pandemic didn’t stop the project nor did it affect the company’s growth. In fact, the Covid year was an exceptional one for Dior; we did double-digit growth versus 2019. We were the only company accelerating instead of slowing down. We saw the curve coming, and you can’t just slow down, you have to accelerate and try to maintain a strict speed. In July 2020, we had our biggest results in our history in terms of turnover. So there was no discussion about stopping the project. In fact, the construction company working here chose to stay at home, but we sued them because they had no right to do that, as construction sites were not legally halted. I asked them to come back because I absolutely wanted to complete this project. It was supposed to be for 2021, but ended up being only four months late, in 2022.

The years you worked at LVMH prior to Dior – firstly at Louis Vuitton in marketing, and then as Fendi CEO – were largely defined by your vision and skill at branding, marketing and communications. So when you arrived at Dior, what was lacking in terms of brand coherence?

It’s difficult to say. Sidney Toledano had done a fantastic job. His situation was very difficult, because Dior had been such a licensed brand and he had to stop all the licences and the franchises, and bring it all back together. He started building the first incredible location, this fantastic location for Dior. He had issues with the creative side, with John [Galliano]; he went through that hard time. When I arrived, I found a fantastic company and a fantastic base on which to build the next phase. A brand like Dior is built over time, over 75 years, brick after brick. I wanted to build a new chapter in its history on that beautiful base. It was my time to start doing things, and while it has only been four years, we have done lots of things. We have three fantastic creatives in Maria Grazia, Kim – I first hired him at Vuitton, and I wanted to have him here – and Victoire de Castellane. I have a fantastic dream team, which is not always easy to handle because they are big characters and they have strong ideas. I have a strong character, too. But I think the brand’s positioning has been based on the idea that I share with these three artistic directors. Dior is the king of dreams, and we are the only brand that was founded on a dream. The likes of Chanel and many others have a great position in the market, but they’re different to ours. My motto when I first arrived here – and it still is – is ‘Dreaming Dior’. We don’t need to invent things, but rather go back to Dior’s original positioning: the dream. The store we’re sitting in right now is all part of that dream.

Looking through the archives in the museum yesterday, it struck me that Monsieur Dior was both a creative visionary and a very astute businessman. Launching the fragrance at the same time as the haute couture, opening up so soon in North America, and so on. What do you think he would have made of this latest incarnation?

I don’t know what he would have thought about his kingdom being run by someone from a small village in the province of Parma! But I think he would be very, very happy about 30 Montaigne being integrated into the boutique. Part of his legacy was buildings; there are six buildings here. He started with this white one that you see there, this hôtel particulier, and he enlarged it because he was a good businessman. I think he would have been proud that they have been brought together finally, because he wanted this unity. Now 30 Montaigne is inside the store, and I believe that would make him very, very happy. Plus, Monsieur Dior was a true gourmand. There is a picture of him in the restaurant here; he liked desserts; he published a recipe book. So that also would make him happy. He now has a cake named after him: the Pâtisserie Dior. This is the packaging [shows sumptuous box], which I think costs more than the cake itself! [Laughs]

‘I had an entrepreneurial spirit as a kid, but I didn’t know I was going to become a business leader. I only wanted to become a football player.’

I wanted to ask a few questions about your own back story and trajectory. Firstly, when you were at school, were you a grade-A student, a slacker, or a rebel?

I was a pretty good student, but not excellent. As a teenager, I was a football player. I played professionally in the second division until the age of 18. My life as a student was very particular because I was living in a small village, taking the bus to school every morning at 7am, studying until 2pm, then straight to the field for training, getting home at 7pm, and going to bed at 8pm, before waking up the following morning to take the bus again. It was hectic, but it really forged my character.

That must have taken a great deal of self-motivation.

It was not an easy life for five years, but it built my inner strength for sure. I was also in the national under-17s team; I was pretty good.

Who was your footballing hero?

At the time I was really passionate about Diego Maradona – he is the greatest of all time.

This must have been when he was playing for Napoli.

Yes, in the 1980s. Arrigo Sacchi was head coach for Parma, before he went on to win the Champions League with AC Milan, and he was my trainer at the time. He actually sent me a book the other day, and in it he wrote, ‘Neither of us were good enough football players but we both chose plan B and finally it shows that plan B was the right one for both of us, and it worked out very well.’ I wrote back saying, ‘You might not have been a good football player, but I was, and you were the one who kicked me out the team without justification!’ [Laughs]

He shattered your dream!

I decided to stay in my little village and continue to study at the University of Parma, where I was a pretty mediocre student. Then I started working in Milan, before going to the USA and then to Germany, where I lived for 10 years. One day I was called out of the blue by Yves Carcelle who asked me to run the communications and marketing at Louis Vuitton. I hadn’t bought any luxury products up to then in my life.

What had been your relationship with consumerism up until then?

I hadn’t had any. Honestly. I was working at [chemical and consumer-goods multinational] Henkel, and living in Düsseldorf; we had a good lifestyle, but I didn’t know anything about contemporary art or luxury. When I came to Louis Vuitton, Monsieur Arnault, and Yves Carcelle told me, ‘Your life will change. Not only because you have a new job, but because you will be confronted by new experiences, your tastes will change because you will meet so many incredible people.’ I could barely comprehend what they meant.

What do you think they saw in you?

I think they probably saw someone very authentic and very genuine with good dynamism and a willingness to always surpass himself.

When I interviewed Monsieur Carcelle 10 years ago, he said he’d been born with an entrepreneurial spirit, and that when he was at school, he was already buying marbles, and selling them for twice the price. Did you have any similar young entrepreneurialism?

My father was travelling a lot when I was young, and he’d always bring back souvenirs – something from his trip to Japan, for example. I ended up organizing all these souvenirs and opening a sort of museum in my house for my village friends. They all had to pay to see these souvenirs. The other thing was that I started a business trading rare Panini football stickers. I had a collection and I started getting in touch with people in Parma to sell Panini to get some money. I did have an entrepreneurial spirit, but I didn’t know I was going to become a business leader. As I said, I only wanted to become a football player.

And when that dream was gone?

I still played football in the amateur leagues just to earn some money to pay for my studies, but I soon got fed up with university; I wanted to open a store selling sports clothes and football boots. That was my dream, to be honest with you. Then all of a sudden, I was hired by this multinational company, Benckiser, and I discovered a whole new world. I learned about marketing, which I’d barely studied at university, where I’d been doing banking. I quickly discovered that I had a real talent for marketing. Around that time, I started working for this one company, Mira Lanza [detergent manufacturers], which was owned by Benckiser, and I learned that these companies were led by incredible people. Jean-Christophe Babin, who is now the head of Bulgari, was my first boss; he hired me. I used to look at him, like this mega-manager of marketing with the beautiful car and the beautiful wife, the Bang & Olufsen – this was my new benchmark. Then, step by step, I met incredible people along the way; Monsieur Arnault and Monsieur Carcelle are the two people who changed my life the most in terms of luxury. Over the years, I’ve had offers to go back and be the CEO of big companies, but I couldn’t go back to mass market.

This 30 Montaigne project was an audacious move, and it has undoubtedly been risky. Are you a risk-taker by nature?

Risk-taking is part of being an entrepreneur; you have to take risks. During Covid we kept investing when the world was stopping – that was a risk. I don’t know the biggest risk I took, but I’ve always taken them. In the mid-1990s, I helped organize a tournament at Giants Stadium in New Jersey, with Benfica, Real Madrid, Parma, and the US national team. I took the risk of putting a lot of money into a football tournament because I thought people would come to the stadium. We had more than 30,000 spectators every day for four days, and we made a lot of money. We probably made more money with that one event than Parma ever did! That was the first risk in my career; I was very young, around 38. Since then, I have taken a lot of risks with every company I’ve worked for: the runway show on the Trevi Fountain with Fendi; moving Fendi into Palazzo della Civiltà, the old Mussolini building, when everyone in Rome said we were crazy. We had to go to the parliament to convince people, and now it has become the symbol of Fendi’s renaissance. I’ve always tried to find ways to put myself into risk-taking positions, but I like to come out winning in these challenges. This was another example, with Covid, when we took the decision to do this. By the way, Monsieur Arnault never asked me how much it would cost, but it was a lot of money and Dior was much, much smaller than this, so technically it could not have afforded this. We are part of a group, so if we failed, it could have been a huge problem for Dior, and if we had not grown as fast as we have over the past years, it would have been out of proportion. It seems completely natural now; it felt much less so four years ago.

‘The first thing I wanted to achieve when I got to Dior was to transform it into a €10 billion company as soon as possible.’

Have you achieved that?

I cannot tell you, but you can read the evaluation made by certain analysts that says Dior has surpassed €10 billion.

Can you describe the first time you met Monsieur Arnault?

I remember it perfectly. I was staying over the road at the Plaza Athénée hotel. The meeting was at 9.30 in the morning. I was taking a shower at 8 o’clock when his assistant called me and said, ‘Monsieur Arnault is waiting for you; you have to come immediately.’ You never say no to him! So I got dressed and rushed over to his office across the street, still with wet hair. We went downstairs and he took me on a tour around the Louis Vuitton store and said to me, ‘If you don’t feel something inside you then just say no, but perhaps you feel a passion about all these incredible artisan-made products.’ Then he said, ‘Luxury is about emotion. If you don’t feel that emotion, then stay where you are.’

To manage a company like Dior, does it have to become a total obsession?

Yes, you have to be obsessed.

Are you thinking about it 24 hours a day, waking up in the middle of the night?

Absolutely. Ask any of my team – I normally answer my emails at the speed of light, within 50 seconds of receiving, night or day. You have to be obsessed. I don’t know, but probably because I consider myself to be less intelligent than many others, so I try to cover it up with a lot of work, a lot of willingness, and being there all the time. I know only this way; it is more than a job, the job is part of your life, and your life is part of the job. The boundaries are very thin. To do what we do with this responsibility, we have to be aware of what is going on everywhere. I don’t know any other way to manage a company than being obsessed.

‘I consider myself to be less intelligent than many others, so I try to cover it up with a lot of work, a lot of willingness, and being there all the time.’

Given the speed at which you make important decisions, are there times when you’ve thought to yourself, ‘If I’d had more time to reflect on that, I would have done it differently’?

No. I am very instinctive, and I am also under pressure – and under pressure you create diamonds. If you have the luxury of time, then you think and you rethink and don’t do what you need to do. That has never been my philosophy.

You mentioned before about working with high-profile creatives such as Victoire, Kim and Maria Grazia. What sets creative people apart from the CEO?

First of all, they are all different from one another; they are very special people, each with a very different sensibility. We kind of create heroes of them, and sometimes it is easy for them to lose touch with reality as they live in this creative world and are under pressure to create collection after collection after collection. They are always trying to surpass themselves; they have this incredible sensibility, and they all need to live with this in their own particular way. CEOs are the ones with more contact with reality, which means dealing with your 10,000-strong family, as we have working at Dior, and you need to prosper economically, which has to support the huge investment we are making in creative talent, and with big fashion shows, and with beautiful stores. In the stores we are showing everything possible to maximize everything the creatives are doing. They need to be able to sometimes isolate themselves from reality in order to exist in another world where they need to keep creating and inventing.

Would you say that your role is about keeping them dreaming and creating?

Yes, we have to protect them so they are free to create as much as possible, to do the collaborations and keep their sense of provocation. I have to have the courage with them to say, ‘Let’s do this’, and then decide with them what is realistic. It is a difficult equilibrium to find, but the basis of this equilibrium is what decides the success or if you are going to the wall. That’s why the relationship between the CEO and the creative teams is fundamental.

This project is clearly founded on creating great brand equity, while forging financial growth. Would you say that a company experiencing great sales but diminishing brand equity is in a more precarious situation than a brand with great brand equity but reduced financial results?

I don’t know if Dior is one of those brands at the moment. I think there are about four brands – don’t ask me to name them, you know them better than me – that have this kind of ‘sacred’ image that crosses time, because of the history and the mythology surrounding them. I think Dior is one of them. Dior’s brand equity will always remain, and the challenge is to maintain the economic growth that mirrors its incredible brand image. If I had to choose another brand whether high or low, I would choose a brand with high brand equity because I know what to do with marketing to make them work! [Laughs]

Lastly, this might seem an absurd question to ask a CEO, but is there a time when big becomes too big? When could Dior’s sheer scale have an adverse effect on that intangible value of the brand?

That is a question Mr Arnault and Michael Burke ask themselves everyday concerning Louis Vuitton, because it is difficult to imagine a limit to Louis Vuitton. If we keep doing a good job and delivering great results, then we can always keep dreaming at Dior. We do not know the limit of our exercise and the potential is pretty unlimited when you think about the middle classes coming up in places like Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia and Korea. I think these middle classes are looking forward to having their reward, their piece of luxury, whether that’s a vacation or a piece of the legend of Dior. So, you know, I don’t think big – I think huge.

Styling by Jean-Michel Clerc.

Models: Ruth Bell at Elite, Selena Forrest at Next, Sora Choi at Ford, Essoye Mombot at Oui Management.

Hair: Caroline Schmitt at Art+Commerce.

Make-up: Jindian Yang at Art+Commerce, Elodie Barrat.

Nails: Nelly Ferreira.

Photography assistants: Tarek Cassim, Tom Ortiz, Clément Dauvent.

Hair assistant: Hyacintha Faustino.

Nails assistant: Delphine Aissi.

Post-production: Catalin at Quick Fix Retouch