How a ‘newsletter about shopping’ became fashion’s most coveted read.

By Rachel Tashjian

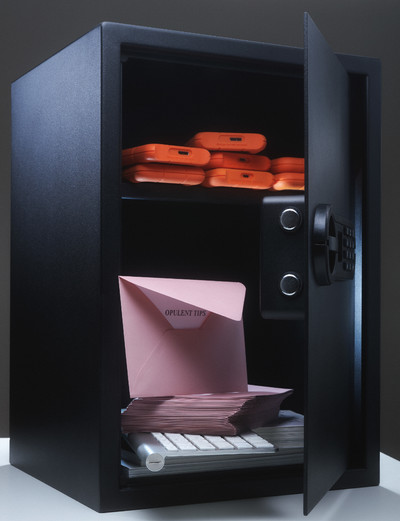

Photograph by Guillaume Blondiau

How a ‘newsletter about shopping’ became fashion’s most coveted read.

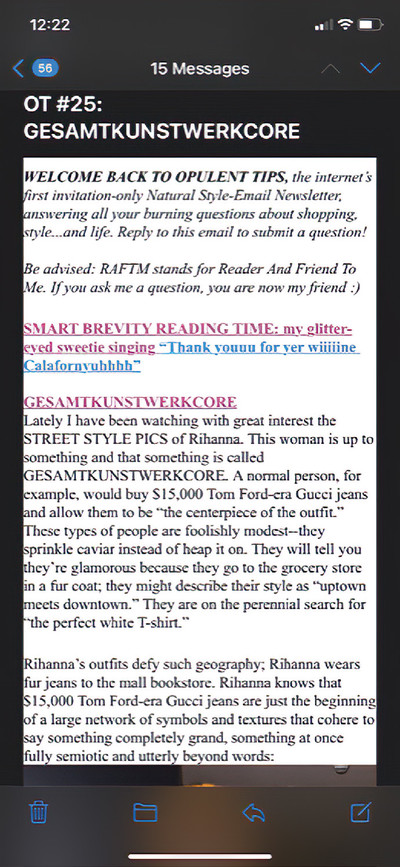

I wish I’d had a grand, devious master plan when I launched the newsletter Opulent Tips in the deep demonic winter of 2020. Mostly, I missed being funny online – having a place where I felt I could play completely, frivolously, and in my own voice – and was a bit tired of getting direct messages on Instagram and Twitter asking me about the best motorcycle boots (Ann Demeulemeester); the least-known movies with amazing style (Robert Altman’s canon!); and whether it was a good idea to buy things from brands they had discovered on Instagram (no). As I think back, I also recall that I was irrationally infuriated (as I so often am!) with the kinds of products and brands that my smart, otherwise well-informed friends were talking about. On top of which, they seemed to know or care nothing about Wales Bonner, Kiko Kostadinov or Marine Serre, or what upcycling and slow fashion are, or the incredible revolution happening in fashion photography. For example.

I wanted a place to act a little crazy, unapologetically so, and Substack (and other platforms) seemed to cultivate a strangely uniform tone of chilled amiability in too many writers. Plus, creating a Substack smacks of ‘I’ve got some personal news…’, and I didn’t want to leave my job as a journalist (I was then at GQ, as the magazine’s first fashion critic) to write a newsletter about shopping.

The only option – or at least the most mischievous one – was to send it out by email in what I deemed cheekily a ‘natural-style’ newsletter. This meant I’d have to manually enter every recipient’s email each week, which would be no problem because I figured only about 50 people – my close friends and some of theirs – would want to read it anyway. I joked that it was ‘invitation only’.

As it turns out, many more than 50 people wanted to read it. I have turned down most of the reader requests – the way I do things is just too unwieldy – but still, I now have some 1,500 readers, which includes many important people holding this magazine and many 17-year-olds who feel wistful about the decades before they were born. (I try to prioritise those two groups.) I’ve attempted to make sense of the success for the past 17 months. Is it because it feels exclusive? Well, yeah. Is it because it is hard to get on the list? Probably. But it’s also because people feel refreshed and energised by this admittedly old-school way of writing about fashion. There’s a lot of apologising or equivocation in fashion writing today, and rarely are young people offered enough access or confidence to write with authoritative panache. (Admittedly, a lot of young fashion writers just haven’t read and studied enough of our forebears.) I see people overanalyse podcasts, ‘prestige’ television, and other garbage from all across the pop-cultural stratosphere, and that kind of attention is always considered serious without regret. Yet, seeing fashion as a subculture, with characters and peculiarities, feels fresh to those of us under 40.

‘I see people overanalyse podcasts, ‘prestige’ television, and other garbage from all across the pop-cultural stratosphere, and that kind of attention is always considered serious without regret. Yet, seeing fashion as a subculture, with characters and peculiarities, feels fresh to those of us under 40.’

Every time I encountered some quirk of the system, I looked to the readers and shaped things to accommodate their requests. (Once, someone asked me for a fashion bibliography, and instead I recommended things based on the most recent fictions reads of anyone who cared to reply. It was chaos! As you can tell, I love chaos.) Readers asked if they could share it; I suggested they take screenshots. They wanted merch; I said that buying something recommended on Opulent Tips was my equivalent of merch. (A lot of merch is pretty wasteful.) The sharing of screenshots and bragging about vintage finds sourced through the newsletter, and in many cases even just tweeting that you’ve received the latest edition, has created a community that extends beyond the publication itself. To read it is to understand a certain sensibility, I guess, or at least to feel like you’re in on something impossible. The trick is that almost nothing I link to is really expensive; I’m a vintage hound, and most people are not wackadoos like me who will scrimp pennies together for months to procure a $1,300 jacket, no matter how many beads it’s festooned with. Often we’re merely there together in the email to appreciate, or come to a better understanding of, a designer or a trend, rather than buy. If anything, I just want everyone to feel more confident at the clothing rack, whether it’s in a store or in their closet. As a result, the newsletter often takes on a Vreelandish cheerleader tone.

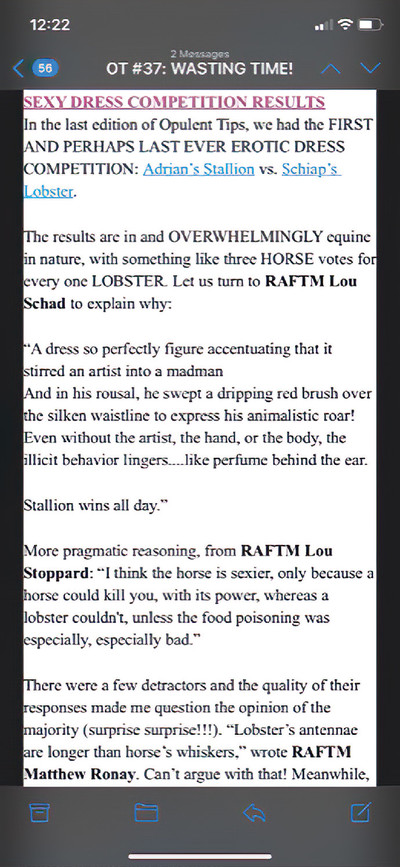

A typical issue includes an introductory essay from me that might cover anything from the Tom Ford going-out top, to a reconsideration of the word ‘chic’, to the Mike Nichols heroine, to solutions to what I call NOEYY or Not Owning Enough Yohji Yamamoto. I rarely link to my professional work, though I might occasionally, because a little fashion gossip (‘Jonathan Anderson took us to the Boiler Room!’ or ‘Stop asking Matthieu Blazy to fix brands and give him his own!’, which I wrote in late 2020, ha!) feels John Fairchildish in all the right ways. I once made a chart of all the brands I cared about on an axis from ‘hype-free consumer to influencer’ and ‘art world to fashion world’; another time, I staged an ‘erotic dress competition’ in which I asked readers to explain which of Schiaparelli’s lobster dress or Adrian’s stallion frock was the sexiest. People share the screenshots on Instagram and Twitter and wishful subscribers pick through them for a taste of the week’s missive. This is especially true, it seems, when I complain about things, like the general state of fashion writing or what passes for sustainable fashion, and it feels like I can rant with my taste as a weapon, which is a nice reprieve. It’s not that I’m afraid of getting cancelled in my other writing – LOL – more that I reserve that space to make the case with hard reporting, which especially in fashion, is difficult and rewarding, and therefore an essential skill to me.

You might wonder, then, why I do this when I already have a full-time job and am established as a fashion critic and reporter. Strangely but perhaps most importantly, doing it has codified my sense of the integrity of my work. A lot of writing today – especially if you’re a woman – is performing online and cultivating a persona, which often comes at the expense of the actual work. (This is ironic because the best literary personalities – Tom Wolfe, Eve Babitz, Toni Morrison – were savagely ambitious and obsessive writers. Except Fran Lebowitz, and I hope she’s not reading this.) Or maybe that’s not true. I think we tend to prioritise the personality over the work it takes to become important, or legendary, or even just the type of person who not only gets assignments but delivers the goods. I didn’t want just to perform, and giving myself a dedicated space to ‘perform’ in – where I would brandish my taste and point of view as an alternative means to examine the culture of clothes – has allowed me to focus on telling stories through interviews, research, and careful weeks or months of observation. It’s much harder and therefore very sacred to me, though being a fashion persona (even if only to a few) is pretty fun, too.

In terms of pure Tips, I think there’s a future for publications that speak to the most niche audience, that project authority about their subject matter, and most of all, that treat fashion as an exciting, rich, textured subject that does not require us to justify ourselves, or worse, explain away our interests. There’s a future for writing in fashion, for both commentary and criticism in addition to reporting, for a sense of intellectual playfulness and ambiguity, which is what the format of the letter allows. My readers and I have an implicit understanding that this is my opinion and mine alone – I don’t want them to do as I say or do, but rather to bring a new level of curiosity to their lives and scepticism to their purchases.