The heart and darkness of Rick Owens.

By Tim Blanks

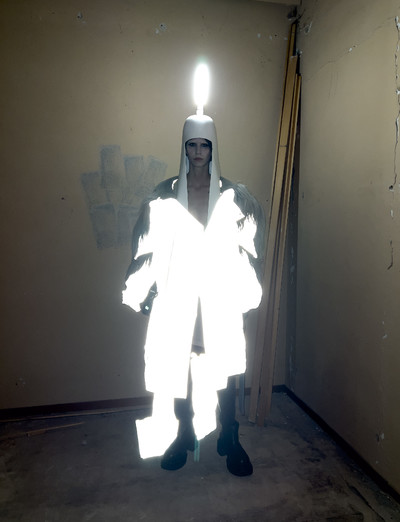

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Creative partner, Dovile Drizyte

Styling by Jodie Barnes

Few fashion designers have so successfully created a world as fiercely idiosyncratic as Rick Owens’. Serving up dark, riotous glamour and challenging orthodoxy are his line of business – and he’s been doing it majestically for almost 30 years. Today, OWENSCORP, the incongruously corporate-sounding business he and his longtime partner Michèle Lamy have built, generates annual revenue in the hundreds of millions.

Along the way, he’s attracted the kind of devoted (read: obsessive) global following more commonly reserved for scaled-up cultish pop stars. To his fans, Owens’s domestic arrangements, cultural tastes, and lifestyle choices (psychedelics, enthusiastic clubbing, committed body transformation) offer a kind of portal into an all-encompassing world. Buying his clothes, it seems, is the entry-level ticket to exploring it.

Now aged 60, Rick Owens shows no signs of slowing down. Au contraire. His recent shows and collections – both during and since the pandemic – have arguably been his most masterful, most emotionally charged, and, at times, most conventionally (and deliberately) beautiful.

With all this swirling in our minds, System was keen to have a closer look inside the Rick Owens story, and take stock of the sometimes turbulent rise, enduring aesthetic, and endearing honesty that are part of his otherwise guru-like presence. Who better than confessional conversationalist Tim Blanks to spend the day in Paris in Rick’s intoxicating company? They discussed life and death, friendships and family, kinks and conquests, mothers and muses.

The following day, Owens jetted out to the Concordia base of OWENSCORP to be photographed by Juergen Teller, before Teller and stylist Jodie Barnes captured an ensemble cast of Owensian beauties who showcase the designer’s recent-era collection archives.

Finally, we invited a dozen of Owens’s most fervent followers to swap stories and ask him their questions. ‘Rick’s like a chameleon in pursuit of beauty,’ says superfan Matt Campo. ‘He imbues his clothes with undeniable ego and brashness, but also genuine sincerity and warmth.’ Reflecting on his own trajectory and success, Rick is humble, grateful, godlike: ‘I sent out a message and people responded. That is the best you can ask for in life.’

Rick Owens is worried we will have nothing to talk about. ‘My story is pretty simple and straightforward. It is not overly complex and I have tried to be direct about it, and I don’t overanalyse things, so everything I say will be a repeat of something I have already said to you.’ It’s not true, of course. Aside from the fact that droll self-deprecation is something of a default position for Owens, it’s a simple truth that the man’s life and work are no open book, whatever he says. They unfold like a lotus, sometimes mystifying, always fascinating. He wonders what he would want to read about himself, then, in a flash, answers his own question: ‘I would want to read gossip.’ And Rick has given fashion tattletales something to twitter about over the past couple of years.

He and his partner of more than three decades, the formidable Michèle Lamy, have built their business OWENSCORP on one of the industry’s most defiantly uncompromising aesthetics, a thrilling combination of eldritch glamour and barbaric futurism. They’ve taken it to the bank and back to the tune of cash registers ringing up hundreds of millions of dollars in sales of clothing, accessories, and the Lamy-supervised collection of brutalist furniture that extends the Owens ethos into the world of interiors. The couple have led a charmed life, uniquely bonded in their challenge to orthodox thought and deed. But there are other challenges greater by far. Take the pandemic, for instance, and the way it has unhinged social stability and, to a depressing degree, simple human reason. Then there’s time, brutal and unforgiving in its passage. As Owens approached the milestone of 60, he found a young male muse, whose Viking visage will be familiar to anyone who saw the designer’s presentations during lockdown. In his perfect physical embodiment of the Owens ethos, he opened a Pandora’s box for Rick of what once was, what might have been, and what now seemed possible all over again. A defiant antidote to tempus fugit, in other words. Even for someone whose sensibility comfortably embraces antiquity and the future in equal degree, that possibility was still a profound shock to the system.

It has taken a difficult while, but Owens insists he has managed to process the inner turmoil, balance his emotional allegiances, maybe even reconcile his past, present and future. In March, he returned to live shows in Paris with what was, quite possibly, the show of his career. Of course, that’s a hard call with a designer who has regularly provoked and stunned over the years. For all the step dancers, death-metal acrobats, penises in full effect, and pyres of raging flame so flagrant in those past presentations, there was something even more powerful about the discreet grace of Owens’s models parading through a Venetian-like fog in their goddess dresses to the strains of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony in the same week that Tsar Vladimir invaded Ukraine. The worship of beauty felt like an act of defiance in the face of fascist ugliness. Ultimately futile, maybe, but breathtakingly poignant in the moment.

What crucible shaped such visions? I’ll never stop wondering, and we’ll never not have plenty to talk about. The Owens geography alone: birthed in Porterville, California, transmogrified on Hollywood Boulevard, transplanted to Paris, working in Concordia sulla Secchia in the Emilia-Romagna, living on the Lido in Venice… but let’s start with the truly wild card. Egypt!

Rick Owens: A while ago, Paris and Italy were a little uncomfortable for me personally. I felt like I was running from one to the other. But when Michèle and I went to Egypt, there was something about going so far out of my personal zone that just put everything back into perspective, and I got all my comfort back. I’ve been twice in the last year. It is just the legend of it I love. I was talking to one of my team members who went to Egypt last month and was so disturbed by the contrast between the haves and the have-nots that he didn’t enjoy it. My perspective was that there is discomfort all over the world, and Egypt to me is more about proportion and space. There is so much. I go to this very old and shabby hotel and there is this emptiness. The Valley of the Gods and these massive monuments that are soooooo ancient, and then desert and scrubland, and a pool. There was something about the simplicity of all that was working for me. It was what I needed right then. And probably it was about mortality, too. I mean, these are monuments built for people who are dead, and this is how they wanted to be remembered. And deciding to be remembered is quite interesting. People talk about legacy a lot, and I guess that is what I am doing. I’m thinking about what impression I want to leave. I turned 60 in November. And there is nothing I love more than reading biographies of weird eccentrics from the past. Michèle is always telling me that I only love dead artists and I’m like, ‘Yeah, because I want to see how it all worked out! I want to see if they were able to sustain the momentum and maintain their conditions to the very end.’ I don’t want to invest in someone who is going to change or turn into a different person.

Didn’t you say once that you are always fundamentally who you are? There is no escape.

Rick Owens: Yeah, I mean that is why I commit to things. It’s as simple as what I wear. I have a uniform that I wear all the time and I have decided who I want to be. Here, let me show you the Vogue video we did.

We pause to watch Rick’s edition of Vogue’s ‘Objects of Affection’, for which he took viewers on a video tour of his apartment in Concordia sulla Secchia, near Modena. It’s a two-hour drive south-west of the Lido in Venice, where he has another apartment, the location for his digital presentations during the industry’s Covid shutdown. In Concordia, he lives across the street from his factory in an apartment as stark as you might expect. The space is partially carpeted and upholstered with army blankets, as all his apartments have been since he lived on Hollywood Boulevard in the 1980s. (‘Inspired by Joseph Beuys, who was my first art hero when I went to art school.’) As he says in the video, he is not very acquisitive and doesn’t like living with a lot of things. Rick is particularly proud, however, of his Egyptian sarcophagus. He waited for a long time for the right one. He calls her Liza, after Liza Minnelli. Rick would have made a wonderful reclusive rock star, à la Mick Jagger in Performance.

You are very, very serious in that video. I don’t think of you as being so serious. Do you think it comes across that way?

Rick Owens: If you know me, then I guess it is a bit deadpan. But anyway, when they suggested it to me, this is what I’d wanted to get, something sedate and calm, not too pop and too lively, kind of a non-flashy alternative designer kind of thing. And it came out great.

Those kids who follow you on Discord are going to go crazy. This will be like Moses coming down from the mountain with the Ten Commandments.

Rick Owens: There is a lot there that’s ripe for parody, like when I say I have 20 pairs of shorts.

When Jonathan [Wingfield, System’s editor] and I were thinking about this conversation at the beginning, we came up with ‘A Tale of Three Cities: Hollywood, Paris and Venice’. But I’m more inclined to two, Hollywood and Venice, because everything that you made yourself into in Hollywood is consummated by you living in that Visconti environment in Venice.

Rick Owens: It is, it is. The full arc.

What does Venice mean? It does feel like an arc completed. How old were you when you first saw Death in Venice?

Rick Owens: I must have been in my 20s. I’m sure it was at the Vista Theatre, a big decrepit barn of a building, with Egyptian gold motifs. I went with my roommate Linda. We were both goths living in a goth house. She went on to be a nursery-school teacher in Seattle. So we go with her bag full of wine and get shit-faced during the movie, and that was the first time I saw Death in Venice.

‘People talk about legacy, and I guess that is what I am doing. I’m thinking about what impression I want to leave. I turned 60 in November.’

Does that come back to you when you’re in your apartment on the Lido? Living right next door to the Grand Hôtel des Bains.

Rick Owens: That is why I moved there. I never read the book, but my first attraction to the Lido was that movie, that era. The exoticism of Venice, how it really is one of the most glamorous places in the particular world that I’m interested in.

How relevant do you think growing up in Porterville is to the fact that you now live in Venice?

Rick Owens: I was propelled, wasn’t I? I mean, if I had had a perfectly well-adjusted sedate childhood, where would I be now? You need something to push you.

Where would you be now?

Rick Owens: I’d be something my dad would have wanted me to be.

Have you seen The Most Beautiful Boy in the World?

Rick Owens: Yes. It is irresistible to compose something with youth and beauty and threat and decline. It’s always been one of the most compelling stories. Glorious beauty, threatened. Of course there is sadness because there is decline at the end. But that is how the world works; there is always going to be a sad ending.

The Most Beautiful Boy in the World documents the blighted life of Björn Andrésen, subsequent to his appearance as Tadzio, the golden youth in Visconti’s Death in Venice. Owens drolly acknowledges that the film adds an irresistibly emblematic edge to his own male-muse situation, but, as he so accurately notes, that story is hardly his story. And, after all, doom – manifested in the gorgeous dying fall of transient beauty – has been a regular Owens go-to over the years. As this issue of System appears, he is presenting his latest men’s collection, in which a blazing globe representing the sun is raised high by a forklift, before crashing to the ground.

Is the collapsing sun your comment on the climate crisis?

Rick Owens: It’s just doom, and frustration with world issues. The sun, goodness over evil, crashing to the ground, destroyed…

Evil triumphs?

Rick Owens: Well, the repetition implies that it doesn’t triumph, it’s just repeating.

You say ‘doom’ with such a dry chuckle, but I know you mean it.

Rick Owens: I console myself with the fact that the good has somehow always managed to triumph over evil. That is always my message. Am I guilty sometimes of romanticising gloom and doom? Maybe. But glamorising it is also a way of processing it because it’s something that is omnipresent. There was another article where I had this sarcophagus and this skull, and the writer was like, ‘How can you live with those vibes?’, and I am like, ‘How can you not live with those vibes?’ Life is about death and threat, and civilisations have got all sorts of ways of dealing with it. Why are there are crosses all over everyone’s houses? It’s to remind us all that Christ suffered more than anyone ever will, and in times of stress and pain, you are being reminded that someone suffered longer or more intensely than you. Suffering is something that you have to get used to, and that is why there are all those depictions of a dying man on a cross. I mean, besides the morality and the spirituality of it, it serves a very practical purpose: to get us not to be afraid of suffering – or at least not be surprised by it.

We talk about Rick’s background. An only child, he was raised in a staunchly Catholic environment. His father, John, died in 2015; his mother Connie, now 88, has had serious health issues. He is moving her from Porterville to Concordia. I think that’s incredibly brave on everyone’s part.

If you’re moving your mom to Concordia, you’re planning on being there a lot?

Rick Owens: As soon as we were able to travel after Covid, I thought of Concordia as the basis of all our survival. We all need Concordia to work for all of us, so I kind of hunkered down there, because there was a bit of restabilizing to do. I always said Italy is where I go to create and Paris is where I go to be judged. Paris is not the most welcoming place, but in Concordia I have a whole army – maybe 200 people – working, so it ends up being a cosier place.

When you have that many people depending on you, do you feel like the shaman of the tribe?

Rick Owens: More like the village idiot. I feel like we are all lucky, I’m basically the goose that lays the golden egg, and we all have to figure out what to do with it.

It seems really gutsy of your mom to move.

Rick Owens: I have a really nice house for her near the factory, with nice high ceilings and a huge garden. Mom is scared of leaving the house she is so attached to in Porterville. It was her sanctuary, the house I built for her across town so she could escape from Dad at a point when he was getting very dark as he got older. He was bitter and angry, and he wasn’t speaking to me for years before he died. She had that house for three years, and every day she would go furniture shopping and buy stuff for it. He thought she was out with friends, so he never knew. She could decorate it how she wanted it without him leaving all his stuff all over the place. He would oil and polish all his guns and then leave them out on the dining-room table, with all the oily mess everywhere. Like a gutted animal. It was a sort of display in a way, like a puzzle for him, and a symbol of manhood and of accomplishment.

Did he use them?

Rick Owens: We would go out target practising. Recently I’ve been to the target-practice place in Venice; it’s like a concrete bunker and it’s where they train the police force, and these guys were like, ‘You should join the police force; you are good’. Apparently I am good enough for the Lido police force. So anyway, I understand Mom’s connection with that house. She is afraid, she is like, ‘You are not going to put me into a hospital are you?’ I’m like, ‘I swear I will never do that.’ But all her friends are dying, and I have to pull her out of there. I told her this isn’t a definitive plan: ‘You have your house there, you have your house in Concordia, you have your family in Mexico, you can circulate. You can do anything you want, and you know I am getting you a ticket with a return flight, so you don’t feel trapped in Italy.’ But it is time to come and see how it feels. She has no choice.

‘My dad would oil and polish all his guns and then leave them out on the dining-room table, with all the oily mess everywhere. Like a gutted animal.’

Is it literally that bad in Porterville?

Rick Owens: All her friends are dying. She was a teacher’s aide for migrant farm workers. She would interpret for them, so she has a following of all these kids who grew up with her as their maternal figure. They visit with their grandkids and they are very attentive, but they’re not her family. I’m the only one, and I can’t be over there that much.

Were you going more often?

Rick Owens: I went for the first time recently in like 20 years, when she started struggling. I have always resisted because I thought I didn’t want to return to a place where I had been weak or struggling or frustrated. I mean, why would I want to remember that? But it was great. I totally underestimated how great it feels to go back at full power. It felt very reassuring and comforting, and very familiar. I was like, why am I in such a good mood here? I was never happy here; this was where I was frustrated and threatened. Why am I happy here now? I am still not sure.

So it wasn’t like Ingrid Bergman and The Visit? You remember that film? She returned to the town where she was raised, where Anthony Quinn’s character had raped her when she was young. She had left town under a cloud, gone off and married the richest man in the world. She inherits his wealth, and then comes back to town, where Quinn is now the mayor, and sets about destroying him by slowly corrupting the whole place and turning everyone against him.

Rick Owens: Why didn’t I do that?

I thought that is what you were going to say.

Rick Owens: I can’t wait to see this movie!

So you went back and felt comfortable there?

Rick Owens: I felt great comfort and serenity there, hanging out with mom in her garden. Yeah, it was lovely.

Did you ever resolve things with your dad?

Rick Owens: There was nothing to resolve really. It was a war that we had together. My dad was such a big lesson because we had always been very frank about everything, like hard-ass blunt. So I didn’t think anything was off the table with him. I had described our relationship as tense because he was very right-wing. In one article I described him as an adorable Nazi, and he was fine with that; he did have a sense of humour. He thought that was funny. But then in another article, I said I had a hard time with what I perceived as his bigotry, and that he couldn’t forgive. Because I would not debate with him, and he wanted to have a debate to prove empirically that he was not bigoted. I was, like, this is just my interpretation. I mean, who am I? But I had a louder megaphone than he did; I had been able to say that in front of everyone, and he couldn’t retaliate with a bigger microphone. That was what broke us. It wasn’t the fact we disagreed; it was the fact that I was louder.

Surely everything about you – the way you were living, the way you transformed yourself – he would have seen as a total rejection of what he was.

Rick Owens: It was, and I have to hand it to him, he was a good sport. He showed up to the shows and he sat next to the drag queens, and he shook hands with the homosexuals, which was amazing. I mean, he bit his lip, but he showed up. So that is impressive.

And he was proud?

Rick Owens: Yeah, he wasn’t gushy, but he definitely said, ‘It is amazing what you have done.’ I mean, he hated it, but he was definitely impressed. But anyway that was the last thing where my voice was louder. That was a lesson because – and this has happened with Michèle, too – sometimes I’ve said something that, out of context, didn’t sound comfortable to her, and while it never became a huge problem, I’ve learned that anything I say in this context is going to change and be amplified once it is printed – and I can’t do that to people I love any more, even though I am dying to talk about them all the time. I would love to, but it is just like a power that is too unwieldly in a way.

After a conversation Rick and I had in March, I was painfully conscious of that amplification. He was trying to clarify his feelings about the presence in his life of someone who was much younger, carefree, vibrant. It was almost as though he was thinking aloud, thinking through a difficult situation.

I was also getting so vulnerable. I have gotten to the other side of it now. When I spoke to you then, there was a lot of desperation, but I have found myself again and found my specialness and my powers.

Thank God for that. You were doubting yourself and I was like, please, no!

Rick Owens: I never doubted what I do; I was just destabilised. There is like this regret when you see this shining example of vitality and you see your reflection in that. It’s kind of, wow, I don’t think I ever was that. There is no way I am ever going to be that in my entire life – and that is a kind of death. There is a mourning and a shock. You know, this is my drama, this doesn’t happen to every single 60-year-old man. It was circumstantial I think.

It’s really hard for me to even conceptualise what sort of vitality you imagine you could have never had. That’s why I’m fascinated by your early life in LA. We’ve never really talked about it. I remember telling you how much I loved the Screamers, and you made a throwaway comment about [the band’s co-founder] Tommy Gear and I didn’t know if that was for real or not.

Rick Owens: That I fucked Tommy Gear?

‘I always thought I looked soft and vulnerable. A little Liza Minnelli-ish. Big, cow-like eyes. An innocent gerbil in the big city, trying to look tough.’

Well, that you were with him [pause for TB’s attack of the vapours]. I fell in love with the Screamers in 1978 and that seems a little… early for this story.

Rick Owens: I graduated in 1979 and my wild years in LA were through to 1985 and then I was with Michèle.

So tell me about those wild years.

Rick Owens: I graduated in 1979 from high school in Porterville, then I worked as a pharmacy delivery boy for a while. They had a truck, and I would deliver pills until… they had a prescription for diet pills that nobody picked up for a long time and I think that was probably a trap for delivery boys. So I took them and then I got fired, but they never said that was why. So I am never really sure if that was it.

Were those the Quaalude years?

Rick Owens: No, it was always speed. We never had good Quaaludes in Porterville. I was mainly drinking, and I think mom could see that I was just going down the drain. I think my school counsellor suggested Otis [College of Art and Design], so mom organised a trip to go see it with me. She helped me get an apartment and she kind of set me up there. I think her friend had a daughter who was living in Los Angeles.

What did you look like at that point?

Rick Owens: I always thought I looked really soft and vulnerable. I was always a bit embarrassed. I looked a little Liza Minnelli-ish… big, open cow-like eyes, innocent. Like an innocent gerbil in the big city, trying to look tough.

And your hair?

Rick Owens: There were so many variations. I mean, after I met [extreme performance artist] Ron Athey, I started doing the spikes like Ron. I had spikes in the front and at the back.

As an innocent gerbil in the big city, how on earth did you meet Ron Athey?

Rick Owens: I got a job as an extras scout, so I was supposed to go out and put together a punk club scene. I saw Ron Athey on the street and I got his number and asked if he wanted a job. He needed a ride, so I ended up driving him to the set. He didn’t have all the tattoos yet. He had a very soft face, too, but he had these eyes that were really evil and then a teardrop here [Rick indicates the corner of his eye], and these hair spikes. He was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen in my life. Anyway, I totally pursued him, though he never really responded. I was going out with Michael, this guy from a band – I forget its name – and he lived with his lover, Spider, who worked at Basic Plumbing, a sex club on La Brea Avenue. They had been together for a long time, so it was fine for me to be Michael’s boyfriend, and we all went to a party in downtown LA on the tracks. Ron Athey was there, and I snuck off with Ron and we had sex on the railroad tracks. I actually already told this story to this cute little punk rock magazine called Insurrection.

I think the Screamers were in a punk movie. Population: 1. Was it that?

Rick Owens: It wasn’t even a punk movie; it was a John Candy movie that never even came out. It was a comedy, and he blunders into a punk club at one point. It was really stupid. So anyway, I’ve been in contact with Ron over the years. Michèle and I would go to his performances years after I met him. He was my age, so we would have been 30 by then, and he had become the performance artist, and we would go see him at Club Fuck! in Silverlake, the thing where he would cut himself, then put the paper towels across his back and string them across the audience. He was spectacular.

‘I stopped drinking because my alcoholism was so bad. They had to give me downers so that I wouldn’t hyperventilate because I had the shakes so bad.’

I’m grasping at chronology here. You moved to LA in 1980?

Rick Owens: It was a year after I graduated from high school. I was still drinking in Porterville and my mom pushed me to LA. And I went to Otis, the art school. For the two years I was there, I didn’t really explore that much. I was very devoted to art school and that area, downtown LA. I didn’t even go to that many punk clubs.

Did you go to the Veil?

Rick Owens: I might have. Someone said they saw me once, but I don’t think so. I went to Power Tools. It was kind of after goth. There was Plastic Passion. There was the Bitter End. Paul Fortune had something…wait, he was the one running the Veil. And in his book he said he remembers a young Rick Owens hanging out by the back door or something. I don’t think I was there. [Laughs] For the two years of college where I didn’t really circulate that much, I had a very small circle of friends. I was kind of quiet, doing art-school stuff, very much in that area, downtown LA, but not the downtown that is fabulous, just art-student-poor-people downtown. I mean, I must have had drive and ambition, but I think the lazy side of me was drinking too much out of frustration and bitterness. My drinking was always very dark.

What would you drink?

Rick Owens: Vodka. Get me there fast; I didn’t have time for beer.

Even at Otis, you were plagued by bitter drinking?

Rick Owens: No, everything there was new; there was probably potential because I was going to school. I was creating stuff; I was going somewhere; I was moving forward. So I wasn’t as self-loathing or frustrated that I couldn’t break through. Then I stopped going, because I just couldn’t afford it any more. I took out student loans and then I got scared of taking out more, so financially it wasn’t working. Then I went to trade school, and there was just nothing for a while.

Were you out at this point?

Rick Owens: Oh, yeah.

Were you ever scared for yourself?

Rick Owens: Oh, yeah, that is why I stopped drinking because my alcoholism was so bad. They had to give me downers so that I wouldn’t hyperventilate because I had the shakes so bad. That was what scared me the most.

Did Michèle try and stop you?

Rick Owens: She would call the doctors. We were living above Swingers, this coffee shop that Sean MacPherson was running. He had the Bar Marmont, and all the cool restaurants in Los Angeles. It was a coffee shop that was also a really funny motel. I had my studio, and Michèle was building her restaurant, Café des Artistes, across the street on Hollywood Boulevard. We were really broke, and that was when my alcoholism reached a peak. I think Michèle and I got together when I was 27, so I was drinking from 25 to 35.

It didn’t all change when you connected with her?

Rick Owens: It wasn’t a huge life change, but it was definitely an alliance. It was very much a soulful connection, like this is my other half. Or like, that we belonged together.

That whole thing about your drinking blows out of the water my notion about you being always in control.

Rick Owens: When I wasn’t drinking, I was always very driven and very organised, and I got a lot of stuff done. But then I would have these three-day binges where I would just pass out, wake up and then just pass out again as quickly as I could to sort of escape. It was very self-destructive.

Riven with self-loathing?

Rick Owens: I don’t think I hated myself, I think there was a sort of gay shame somewhere from my dad, my family and Porterville. Also all that energy and ambition that was not coming to fruition… I think that was what it was. I was shy, so I needed courage to demand the attention or the validation that I craved.

And you thought that drinking brought out the attention?

Rick Owens: No, no, it gave me the courage to go out and be somebody. Then when that wasn’t fulfilling, it just comforted me. The other thing I have learned is that when you are expressing yourself creatively, the people who do so successfully are successful because they have a higher sensitivity. In the worst of circumstances, that can translate into being a drama queen. I get to be poetic, that is my job, to try and create poetry and to try and make compositions of things that feel emotionally compelling. The bad side to that, though, is that in your personal life, you can be overly romantic and over-idealistic, overly emotional or sensitive. So there is a drama-queen side to it. And that is what happened to me. I wasn’t drinking for attention but trying to get attention for the work I was doing. The drinking was to give me the courage to go out and pursue it, that was the attention I wanted. I wanted to be validated. I didn’t perform; I wasn’t a performer. I stopped because I really thought I was going to die. So it was fear. It wasn’t anything noble, just dumb fear.

When you stopped, could you look at where you had been and understand why you had been there?

Rick Owens: Yeah, I was frustrated. I thought I was a failure.

And when did you stop?

Rick Owens: I did my first runway show in 1994; I stopped drinking maybe a year before. But I was doing clothes for maybe five years before the show. I sold to Charles Gallay, Bendel’s, Joyce, Charivari…

So you were doing all that while you were drinking yourself to death.

Rick Owens: Yeah, I was getting a lot done. That was who I was. I was a big drinker; Michèle was, too. We drank a lot together, so it made sense. We were a perfect match.

When did your physical transformation begin?

Rick Owens: Very soon after we got together. I was an office boy at this architectural administration firm. They were very charming, very bohemian, very sophisticated. They would do these hand-drawn architectural illustrations for potential buildings, like handmade renderings. The owner was the main illustrator, and we were in this really charming sort of Spanish building downtown. It was very World of Interiors. These people had a very clear line about what was ostentatious or tacky. They would have office parties and invite people to look at slides of their latest Italian tour. It was a great environment. At the same time, I started going to fashion school to be a pattern-maker. Art was too hard. I didn’t understand it enough; it was too cerebral for me. There were these art-theory classes that were so abstract and intimidating and I just thought I can’t be an artist, I don’t get all that. They scared me out of pursuing being an artist, so I thought: ‘Well, I am smart enough to be a designer, so I’ll do that.’ So I went to design school and then I got a job as a pattern maker in the garment industry downtown. I was doing patterns and kind of fast-fashion patterns and then somebody told me there was a job at Michèle’s label. I went there and the rest is history.

Did she interview you for the job?

Rick Owens: She did. I had a nose ring, and I wore a long durag in this very beautiful brown silk jersey that I found in a hat-trim place in downtown Los Angeles. I must have worn make-up. I don’t know what I was trying to do.

And your hair?

Rick Owens: It was always black, and very wavy.

So you must have looked kind of cholo, very masculine.

Rick Owens: I think I did, but I was super, super white. For some reason, I had very pale skin. Michèle had all the jewellery and the bracelets. She was more kittenish then, very languorous. We didn’t hook up for two years because we didn’t do that much in the factory right next to each other. She just passed by. She would sometimes have a party at her house and I would go, or we would run into each other at clubs. Stuff like that for two years because I didn’t really know her.

And what was the trigger to connect?

Rick Owens: I mean, she was so adorable and cute, and had such great body language and style. We were just drunk one night, and I made a move.

And you had been gay up until then?

Rick Owens: Yeah, I mean I had a girlfriend way before, so I wasn’t completely innocent, but she was just so cute. She was married, but it was all very casual and bohemian. I don’t remember any confrontations. I just remember one night at the club, Michèle and I were there, and I had my arm around her and then Richard [Newton, Lamy’s first husband] showed up, and he had a drink with us, but it was like nothing. Like we knew it was a moment where decisions could be made and things were being revealed and an understanding was being met, but no one really said anything.

‘I had soft nipples, and softness in the thighs and belly. Then I took steroids and worked out with a trainer, and it bulked me up and I got really thick.’

One thing I was curious about in LA was the way that AIDS decimated things.

Rick Owens: I was going to bring that up. Death was everywhere. Friends of mine were always going to funerals. I wasn’t though; I went to, like, two. That period was my sex period, but I loved the sex clubs, that was where we would go every night. That was my clubhouse. And it was just being in an extreme, exotic environment, where everybody was going as far as they could go.

And you were a voyeur?

Rick Owens: No, I participated, very gleefully. That sounded a bit boyish.

I once walked past [legendary New York club] Mineshaft and I was kind of sorry I never went in, but it just smelled so bad.

Rick Owens: Yes, but that was part of it. You see, I’m a pig, you’re not. I had kind of a prissy childhood; my family was a little puritanical but also very prissy about hygiene, so those were forbidden fruits, to be in that environment. By the way, when I was in grade school, I was terrified about having to go to high school and be naked in the showers with other boys. That made me so uncomfortable. Then when it finally happened, obviously I was super uncomfortable and really, well it was just terrible… I mean, it’s not like anyone did anything to me, but my sexual tension and that environment with all of these guys, all that masculinity. Like the games when you had to pick the teams? Finally in the end, they would just let me sit down and read. That masculinity was so threatening to me. All that nudity and sexual tension was a nightmare to me. So when I came into my power, I took over that space. I had power suddenly. I could recreate that situation with me winning.

That’s why I mentioned Ingrid Bergman going back to that town. You restructured.

Rick Owens: Well, a lot of what I put on the runway is vengeful. Showing exposed dicks on the runway, showing dicks indifferently… it was after Dad passed, but having a puritanical father whose machismo was so sacred, for me to do that would have killed him.

Do you think it’s that fundamental? That there’s this kind of Oedipal challenge through your career, that you’re creating with your father on your mind a lot of the time?

Rick Owens: Your father is your god when you are young, so everything you do is based around seeking approval from that god or dealing with the rejection. Also, because we were in a small town with no relatives or no cousins, I didn’t have a lot of other kids around. I was kind of a lonely child. Our little Catholic family was very insulated.

He also denied you access to all the things your peers had, like television.

Rick Owens: Now, looking back on it, that was a great idea and worked out pretty well.

Listening to Wagner didn’t compensate for missing The Munsters though.

Rick Owens: I hated it! I hated having to sit through all that music.

‘I loved going to sex clubs every night. It was just being in an extreme, exotic environment, where everybody was going as far as they could go.’

As an only child who was close to his mom, did you gang up on your dad?

Rick Owens: We were both afraid of him, not in an abusive way, but he was very dominating. And mom had grown up in a Mexican Catholic family and was very conscious of her position as a wife and mother, and what was expected of her. I guess we did protest together a bit, yeah. I did mention sex clubs to him as a provocation. I never really considered it, but I think the revenge I looked for was over the past. Here was a guy who grew up in a certain time in a certain way. I always thought that mom and I felt really bad for him; we felt that he had problems, like he was emotionally stunted, so we protected him. We knew that all of this came from fear and self-doubt and insecurity and vulnerability. We both felt protective towards him.

What do you see of him in you?

Rick Owens: Bigotry, and I see ‘judginess’. I also see that I have a set of rules that I think should apply to everybody; I catch myself being narrow sometimes and it is almost like a genetic disease that I am really aware of. I have to be careful not to disapprove. I can also go in the other direction, and not make up my mind, and always play devil’s advocate. I have this moral superiority and then I feel that I overcompensate to make up for it.

Does that sort itself out with time? Do you feel you are mellowing?

Rick Owens: I feel very mellow in relationships. I feel you need to let a person be who they want to be; you need to be happy with what they can give you and not expect more. You can’t expect one person to satisfy all of your needs. I have been telling myself these things over the past five years. I think that has evolved. On the other hand, with the clothes I am making and what I am trying to do with the company, I feel more ferocious than ever. And on the other hand, I feel frustrated with this world’s moralism.

For years, you shied away from any political connotations in what you do, and now you are embracing them.

Rick Owens: Everything is political. I always think of the human condition, for sure. I don’t like to address specific things that are happening in the world. I never feel like I have the authority to make great political statements; that is something that my father would do. I don’t feel like I studied enough to have that kind of authority. But I do know, and I understand how to protest. I also understand that what I do cannot correct anything. It is only ever a protest, but that can be good.

You’ve said that you choose politeness over defiance, which I thought was strange, even though you are an incredibly mannerly and gracious person.

Rick Owens: There is a lot of defiance in what I do, in a nice way.

What about the last women’s collection? Admittedly, the collection was done before Putin invaded Ukraine, but you were able to recontextualise the show by using the Mahler symphony rather than what would have been one of your more typically aggressive soundtracks. At that moment you chose to exalt beauty as a defiant gesture, and it was stunning. Where do you feel you are now?

Rick Owens: It was all so sad; there was a definite melancholy to it all.

Melancholy in the light of the context you were showing it in?

Rick Owens: I hadn’t really thought about that.

There is a rich seam of melancholia in much that Owens makes. The sense of lost worlds is strong. He can convincingly equate Babylon in 2000 BC and Hollywood in 1920 AD. The common thread is scale. The human form is elongated, exaggerated, swathed to create an illusion of almost superhuman glamour. The illusion is often confrontational, monstrous, even, but there is an extreme beauty in the strange. It was less extreme in the last women’s collection, where even Owens acknowledged the classical beauty of his bias-cut gowns. An unwitting synchronicity with world events made those dresses a peculiarly appropriate fashion response to the bottomless ugliness Vladimir Putin was unleashing to the East.

Old Hollywood was a frame of reference for you. How? When? Why?

Rick Owens: In my dad’s basement library. I remember it always having a sense of dissipation that corresponded to Hollywood Boulevard. Maybe the fact that it was buried under the house. It was always shadowy. Those books didn’t belong on the real bookshelves in the house; they were in the basement. It’s not like they were dirty books. I mean, we had the Marquis de Sade upstairs; I was free to read that.

The sense of Old Hollywood is one of the most poignant things in your work, the way you ravishingly recreate the atmosphere, the shadowy, bias-cut languor, the beauty of those dresses.

Rick Owens: Black-and-white movies in the basement. It was the imagery and the environments, too. Theda Bara’s boudoir! That kind of life, that kind of scale. All those Cecil B. DeMille movies, the scale was so huge. Living in these monumental sets, the dresses dragging on the floor… Oh, is that dress going to get dirty? People weren’t asking that back then. It was beyond that.

The whole thing about fashion in LA is that it did exist in a hothouse. It was the most influential fashion in the world in a way, in that people saw it in the movies.

Rick Owens: It really was the Hollywood thing – that was the only reference that there was in LA. Nothing contemporary. I had the most beautiful apartment, a block above Hollywood Boulevard, part of the top floor of a house, a bedroom, a living room and a little kitchen. And I had a black T-Top Camaro with a V8 engine. I had such a tight little driveway that I don’t know how I got in and out after a long night. Not always successfully, because the car ended up getting kind of scratched up. I remember looking at Southern Crescent Heights and dreaming of living there, because the buildings just looked like something out of Armistead Maupin, with an eccentric landlady and someone playing piano in one of the apartments and the fountain tinkling in the courtyard. It just seemed magical. And I was like: ‘Wow, I’m going to live here some day.’ And now… [a single Owens eyebrow flexes at the wonder of it all].

‘For me, having a puritanical father whose machismo was so sacred, to show exposed dicks on the runway while he was alive would have killed him.’

You’d never go back.

Rick Owens: Oh God, no! I could see myself living there, but only on an estate with peacocks and maybe a tiger or two. Then it could be great.

What is your favourite representation of Old Hollywood?

Rick Owens: My main one is Cleopatra, the Cecil B. DeMille movie with Claudette Colbert, the most improbable Cleopatra ever; you couldn’t have picked a worse one. The entire thing is entirely ridiculous.

Theda Bara’s real name was Theodosia Goodman. Claudette Colbert’s was Lily Chauchoin. Nothing and no one was real in Old Hollywood. It was all self-invention. One of the first conversations we ever had, you listed everything you’d done to yourself, like you were trying to coach me to believe that everything I was looking at was entirely artificial.

Rick Owens: Not entirely artificial, but definitely ‘manipulated’.

Self-invention.

Rick Owens: Yes, self-invention. The funny thing is, I can’t do fillers. I tried Botox and I couldn’t tell the difference. I can’t go there, but I did steroids for a time and that really helped. It got everything in place.

What’s ‘everything’?

Rick Owens: Before the steroids, I had softness. I had soft nipples; I had kind of little girl’s boobs, and softness in the thighs and belly. When I took the steroids and worked out with a trainer regularly, it bulked me up and I got really thick. I have pictures of me that are kind of shocking. Then when I stopped the steroids and dropped all the weight, all of a sudden this framework of muscles and the nipples got harder. It kind of created a scaffolding inside of me. It was probably 30 years ago when my body transformed.

And that was something you did for yourself?

Rick Owens: Michèle got me started. She was going to the trainer, and she was like, ‘You should go; you drink too much. It’ll be good for your hangovers.’ So I did and then it just kind of stuck. And then when I saw things changing, it was just addictive. Also, it just felt like being the best that I could be, like doing everything I possibly could. Probably at that time it was also a satisfying sort of control. More than the results of my career maybe. It’s not like things were going badly, but it was just insecure. You don’t know if the whole fashion business thing is going to work out. So controlling my body was one way of feeling in control.

A few months before he died, Thierry Mugler told me that his body was the thing that he was proudest of – from ballet dancer to that massive man mountain!

Rick Owens: He was so handsome. There is a Rudolf Nureyev biography on Netflix that I have been watching it with the sound off. It’s just so beautiful, the old imagery of him dancing and leaping.

So sad.

Rick Owens: Why? I look at his life and I think it was a triumph. It was just glorious. Of course, there is the decline at the end. There always is; there has to be.

Do you see that for you?

Rick Owens: I do admit the reason that I am reading biographies is to see how they negotiate and live their entire lives. Yeah, because I am 60, things are changing. I am thinking about the next chapters. I am really conscious of how people did things.

When you read these biographies that have a beginning, middle and an end, has anything ever stood out for you about how you would like your life to be? Will it end with people loving you for posterity?

Rick Owens: I feel like that is going to happen; I’m not worried about that. I have people who care for me, and I feel that unless I do something incredibly stupid, I will leave a body of work that has a sense of purpose and honour. Yes, I feel good about it. Though it was kind of shocking to me that I could be so emotionally vulnerable. Maybe I am reading these biographies to reassure myself that people can be a little bit messy, to reassure myself that I am not doing it all wrong.

How is your balance of Apollo and Dionysus sitting after the past few years?

Rick Owens: Oh, Apollo, definitely! I tried Dionysus and it wasn’t for me. It has to be Apollo.

‘I could see myself living back in Hollywood, but only if it was on an estate, with peacocks and maybe a tiger or two. Then it could be great.’

Do you actually like the fact that life is still capable of surprising you, just when you thought everything was set?

Rick Owens: I think a couple of things have happened. In the beginning, I maybe went overboard but this last collection is more stabilising. Like all my influences, I have balanced them out better and probably filtered them better. Maybe analysing relationships in general fed into that, just living in my emotions more than I used to.

I felt like in that last collection there was so much less ambiguity than there is usually, like you wanted it to just be beauty at its most breathtaking, rather than challenging.

Rick Owens: Yeah, I don’t know where that came from actually. I know what you are saying about challenging beauty; I do react against the standards of beauty. The laws are so rigid, every advertisement, every Instagram post – there is just such a narrow set of parameters of beauty. I always try to push that a bit because I resent being told what to do. And also because I think there are other people out there who are feeling left out of that whole world, and they want something different. So that is what I am always trying to explore. And it is tricky. I can’t go too far because then it is impossible for anyone to relate to it. But this one did get pretty close to classical beauty. Though I always want everyone to be covered. I want the freaks to be covered, too.

You do have a following that is a little more intense than the average. How do you feel about that?

Rick Owens: It means it’s working; it means that what I put out there has a reason for polluting the world with our dyes and our extra fabrics. We have an excuse; we have a reason to be here. I see the kids in it, and I am like, ‘Wow, they wear this stuff so beautifully.’

Could you ever have conceived of success like this?

Rick Owens: No, I don’t think so. Though I’m not really sure. There is something in me that remembers I would be frustrated about having to balance my check book, and there was nothing really to suggest otherwise. I just somehow knew I would never have to do that. Like, OK, I will do that now, but I will never have to do that in the future.

So you believe in manifest destiny?

Rick Owens: Could be. Maybe I was just a spoiled and pretentious kid from Porterville.

Are you happy now?

Rick Owens: Yes, I am. I got myself together. I figured shit out and I’m not such a pussy with the whole relationship thing any more.

Models: Djo Bibalou, Omar Fall, Niki Geux, Benas Lipavicius, Sebastian Owsianka, Tyrone Susman, Tanya Saru, Edoardo. Hair: Liv Holst at W-MManagement. Make-up: Daniel Sallstrom at M+A Group. Casting AMC Casting. Photography assistant: Tarek Cassim. Styling assistants: Marco Venè, Giovanni Tritto. Hair assistant: Claire Sandra Manuella. Make-up assistant: Charlotte Murray.