How the American couturier Charles James left his sumptuous mark on the de Menils.

By William Middleton

Photographs by Robert Polidori

How the American couturier Charles James left his sumptuous mark on the de Menils.

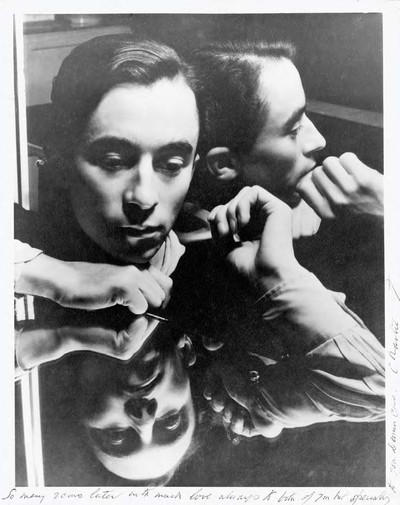

As the Franco-American art patron Dominique de Menil wrote: ‘Among all the people who have a name in the art world – the movers, the doers, the poets, famous couturiers, culinary chefs; anyone, finally, who has a right to a signature – let us place a forgotten name: Charles James.’ Known for his sumptuous evening gowns in icy-coloured silks and satins that had been sculpted into bold, sensual shapes, Charles James was the greatest couturier America has ever produced. In a career that began in his mother’s hometown of Chicago, included important stints in London and Paris and ended in New York, James dressed the likes of Marlene Dietrich, Standard Oil heiress Millicent Rogers, social leaders such as Mrs William Randolph Hearst, Mrs Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney and Babe Paley, as well as Dominique de Menil. Christian Dior credited James as the inspiration for his famous ‘New Look’. Salvador DalÍ stated that his white satin, down-filled evening jacket of 1937 – now in the permanent collection of the V&A – was the first piece of soft sculpture. Balenciaga said that James had raised fashion ‘from an applied art form to a pure art form’. Azzedine Alaïa, who has a significant collection of his work, has said that if he were ever to meet Charles James, he would probably just pass out.

Despite all the accolades, the designer, however, was never able to build a viable business (he could have used the help of a Pierre Bergé, a Giancarlo Giammetti, a Bernard Arnault). Long- forgotten by the general public, James is now the subject of two major museum exhibitions. At the Costume Institute

at the Metropolitan Museum, Charles James: Beyond Fashion (8 May-10 August 2014) will be a complete retrospective of the designer’s work. While the Menil Collection, the museum founded by Dominique de Menil, will host a more personal examination of the designer and his client with Charles James: A Thin Wall of Air (31 May-7 September 2014).

Dominique and John de Menil came to America from Paris in 1941, the year after Charles James settled permanently in New York. The de Menils, however, went to Houston, Texas, where the American headquarters of Schlumberger Ltd, the oil services company founded by her father (she was born Dominique Schlumberger) was based. The couple took a look around the young city, with only the thinnest cultural context, and decided to do something about it. They were invigorated by the sense of possibility in 20th-century America and the frontier spirit of Texas. They quickly became art collectors and patrons, amassing over the decades some 15,000 works of art from Paleolithic bone carvings to Surrealist works by Magritte and Ernst to the great post-War American artists such as Rothko, Rauschenberg and Warhol. They always maintained a townhouse in New York, an apartment in Paris, a country house in the Oise and her family chateau in Normandy, the Val-Richer, yet they concentrated their artistic activities in Texas because they felt it was there that they were needed.

‘Azzedine Alaïa, who has a significant collection of his work, has said that if he were ever to meet Charles James, he would pass out.’

In 1987, Dominique opened the Menil Collection, a museum designed by Renzo Piano – the architect’s first building in the United States and still considered his masterpiece. Just as the de Menils were taking their first steps towards collecting, they met Charles James in New York. By 1947, Dominique was wearing his elegant gowns. In the next few years, as they built their house in Houston, designed by Philip Johnson, they called on James to help with the interiors. In contrast to the strict, Miesian forms of the architecture – long and lean in glass, steel and brick – James produced an interior that was curved, rich and voluptuous. The de Menil house is the only interior by Charles James that is still in existence.

The couple had an ongoing relationship with James as patrons and as friends. That was something of a rarity, for the designer was a notoriously difficult character. His correspondence with Cecil Beaton, who had been a friend since both were at Harrow, is filled with James’ fierce accusations of personal treachery and professional betrayal, both real and imagined. When legendary New York fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert testified against James in court, she stepped off the witness stand to find him charging at her with outstretched hands going for her throat! The de Menils, through their long personal relationships with artists, were understanding of his behaviour. ‘Great artists can be difficult, dissolute, but they are never base,’ announced John de Menil, ‘And in their quest for perfection they come closer to eternal truths than pious goody-goodies.’ The de Menils cared most about James’ talent. They acquired and donated some of his seminal works to the Brooklyn Museum, now key pieces of the collection at the Costume Institute. And she wore his designs throughout her life. ‘I have followed his works closely,’ Dominique de Menil wrote. ‘I have watched the stream of ideas that constantly flows out of his amazingly creative mind and eventually oozes throughout the fashion world. Someday that story will be written.’

To track down the tale of the singular designer and his equally distinctive clients, Susan Sutton, a curator from the Menil Collection who is organising the James exhibition, invited System into the de Menil house. We sat on a remark- able curved sofa by Charles James – in front of a dark grey wall with an important 1967 painting by Max Ernst, Retour de la belle jardinière, and vast expanses of glass opening onto tropical gardens – to talk about James and the de Menils.

‘Great artists can be difficult, dissolute, but in their quest for perfection they come closer to eternal truths than pious goody-goodies.’

William Middleton: You are an art curator – how has it been to work for the first time on an exhibition involving fashion?

Susan Sutton: It’s been a huge learning curve. The museum has never mounted a fashion or design show before. No one in the museum has had to delve into an encounter with this kind of material, so this has been invigorating. It’s opened everyone’s eyes – curatorially, in conservation, in exhibition design . As a curator, there is this balance between approaching these garments as art objects and as their own unique entity as fashion. As fashion, it has its own rules, its own demands that are unique and special. But at the same time, they are also art objects, so they abide by those rules and have similar demands. It has been interesting to ride that line, to have feet in both realms.

Charles James said, ‘I spent my entire life making fashion an art form.’ In 1975, when James was the only fashion designer ever to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship, American artist Robert Motherwell said that James’ drawings ‘were more powerful and to the point than any of the work submitted by so-called artists – that is painters and sculptors.’ His clients talked about how perfectly engineered and sculpted his works were. So, Charles James: artist, architect, sculptor, engineer or fashion designer?

All of the above! His complexity – his artistry – really comes from the fact that he was an engineer and an architect and a sculptor. And I would say a philosopher, as well. When you think about his theoretical thinking on form and shape, his exploration of how to create forms on the human body. That’s really where the greatness of his work lies, in the labyrinth that he was.

How do you characterise his importance in the field of fashion?

From having worked with the materials, I would say that there is this trans- formative quality to his work. It has these transmutations and reimagining of what the body can do and what the body can be. There is a fantasy that propels his mind forward – that seems to be what drives his innovation and makes him such a compelling figure in the history of fashion.

He could also be a bit of a monster. Have you come across any examples?

Well, there are stories. [Laughs] When he was called down here to pick the colour schemes for this house, he would arrive late after all of the painters had already gone to lunch. He would then be frustrated and annoyed at everyone. It wasn’t until later in the day, as all the workers were packing up to go home, that he would really start mixing colours. Daughters Adelaide and Christophe de Menil had to hold flashlights in the dark because the house didn’t have electricity, while he mixed these colours and painted samples on the walls. This insistence on creating in his own time, in his own way and on his own schedule speaks to that temperamental nature.

Charles James died in 1978, in his apartment at the Hotel Chelsea, having alienated the great majority of his friends and business associates. Dominique de Menil was a friend and patron until the end – why?

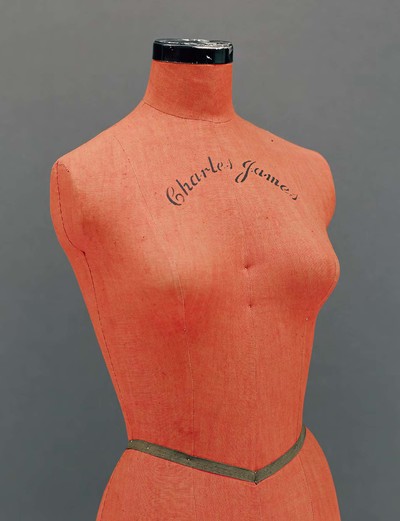

I see it as part of their loyalty to art and to artists. They viewed and esteemed James as an artist, first and foremost. He was demanding in his thinking, in his approach to fashion. They showed a loyalty across the board to him. They were interested in his stunning designs, such as the ‘Butterfly Dress’, but they were also interested in his working process. For instance, they valued his mannequins, his pattern-making – we have 17 drawings that he created for jewellery design. He had proposed flexible sculpture to her, and we have drawings of that in the collection. He was thinking sculpturally, and they were intrigued by that. So they were interested in his full repertoire, his full process and his fullness as an artist. I think they had a huge spirit of generosity and tolerance – they understood that he came as a package with all of these foibles or complexities.

Charles James said that a designer should dress the personality. What do you think the pieces he designed for Dominique de Menil have to say about her personality.

There is a certain understatement in Dominique de Menil’s James collection. There is a sense of the pragmatic in the clothes, but there is also the unusual and the dramatic. The colours are rich, warm and mysterious. So many times working with the pieces we’ve felt like we’re looking at the interior of the house or get the feeling of being in a Surrealist painting. A wonderful example is an evening gown of black velvet and satin with a brown wool-silk over skirt that becomes a bustle at the back. It is a striking combination of textures – luxurious and subdued – velvet and textured silk. And the brown, a sort of mink or milk chocolate, is surprising for eveningwear. There is a mixture of earthiness and elegance that seems to capture something of her personality. She also had a predilection for day suits, afternoon dresses and many coats. She wore many of these pieces again and again, long after they were created.

‘James’ complexity - his artistry - comes from the fact that he was an engineer, an architect and a sculptor. And I would say a philosopher, as well.’

What is the idea behind the exhibition – it’s not meant to be a retrospective.

Right. The story of this exhibition goes back to her meeting James, beginning to wear his clothes, commissioning his work, and then the very audacious move to bring James down here to do the interior of their house. Our look at it is very personal, studying the relationship between client and designer. We are also able to explore the thinking of a designer outside the realm of his main practice of fashion. What does James look like when he operates in the realm of space – an inhabited space, an interior? Our unique opportunity is to look at the symbiotic relationship between furniture, interior and fashion. But we are also looking at personal relationships, which is really what drove the de Menils, what created their collection, what caused them to be loyal to artists and to support them. That is also very much at the heart of the exhibition.

How did you settle on the title for the show, Charles James: A Thin Wall of Air?

In The Genius of Charles James, the catalogue for the 1982 Brooklyn Museum exhibition by Ann Coleman, there is an essay by Bill Cunningham. He describes the great designers of the day as being captivated by James’ theory of a ‘thin wall of air’ that existed between the body and that fabric, which provided the means of transforming the wearer’s body. James believed that it was one of his greatest achievements. What struck me about the phrase is that it refers to his fashion design theory, wholly unique to him, and it also manages to encompass, as James does – the idea of sculpture, engineering, architecture. Perhaps most poignantly, it is also suggestive of relationships and proximity – the closeness of the de Menils to James. It also calls to mind the beautiful tensions that exist in James’ garments and those that his intervention in the house create: opacity and transparency, heaviness and lightness, richness with airiness.

Approximately how many pieces of Charles James are currently in the Menil Collection?

There are 50 garments, 51 if you include fabric that was slated for a dress. Then we have five pieces of furniture, 55 drawings, seven prints and photo- graphs as well as one small sculpture. It’s really quite a wonderful sculpture: a small piece in brass, rectangular, with this figure eight form in the middle. It’s his calling card: infinity. And it is nestled within a faceted mirror, so you have this infinity form moving back on itself. It’s a profound piece that speaks to his thinking: mirrors, reflections, repetitions that move a design forward.

Tell me about some of the pieces in the exhibition that stand out most to you. First, eveningwear?

The first that strikes me is that black velvet and brown silk bustle dress I mentioned. The combination of muted, taupe-y brown, a woolen silk and a velvet bodice – it really reads like Dominique de Menil. There is this luxury and richness, but the bustle fabric seems quite humble to me. So it is about richness and restraint. Another of the evening pieces that really stands out is the ‘Ribbon Dress’, with its sleeve- less, black velvet bodice and long skirt of alternating shades of satin burgundy, chocolate and pale pink. It is fetch- ing and joyous, maybe somewhat like wearing streamers. And it has a highly unusual feature where the dress angles out below the waist and then down. She wore the gown to the opening of Out of this World in 1964, an exhibition of landscape paintings at University of St. Thomas in Houston. A society column described Dominique de Menil in this dress as, ‘chic’ and that she, ‘dashed from picture to picture.’ I can only imagine how different this dress must have been for 1964 Houston, how it would have stood out amongst other evening gowns. We also have this incredible damask evening jacket – it’s this saffron colour with a lining in robin’s egg blue. It calls to mind a Chinese empress. I love it for its shape and drama. And we have a photo of her wearing the jack- et with Philip Johnson, from the early 1950s. He’s talking into her ear and she has this big smile on her face. This triad of Dominique de Menil, Charles James and Philip Johnson that is captured in this unassuming photo really speaks to the house.

‘His theoretical thinking on form and shape. That’s where the greatness of his work lies, in the labryinth that he was.’

Daywear?

There is this mauve wool suit, a skirt and jacket, that I think is one of the most gorgeous daywear pieces in the collection. It has a single button at the top with a stand-up collar. The mauve colour is exquisite, and we’ve paired it with a rose silk blouse, while the jacket is lined with a black fur. It’s simple and yet very dramatic. She gravitated to wool suits, with many variations in black. She is wearing another one in a photo here in the garden atrium, from 1952, with Max Ernst. Again, what I like about that one is the humble exterior, unassuming with some beautiful detailing with a crossover lapel and peplum, but then you open it and there is this incredible lining in pumpkin orange satin.

In April 1984, the exhibition La rime et la raison opened at the Grand Palais in Paris. It was the first time the world had a full look at the extent of the family’s collection. Dominique appeared at the opening, flanked by François Mitterand and Jack Lang, in a Charles James suit.

That was a shorter jacket with a higher-waisted skirt. She also wore that suit with Max Ernst at a 1973 exhibition that opened here in Houston, at Rice University, pairing it then with a pair of tall black boots. So she was incredibly loyal to these pieces. The opening of La rime et la raison was such a huge moment for the collection – that she chose a James suit is significant. She wore it, even though it was more than 30 years old, with a real elegance. She also paired it with one of the iconic Four-Leaf-Clover Hats.

Which brings us to accessories – which stand out to you?

There are two ‘Clover Hats’ in the collection. One is a velvet with a braid around the perimeter. The other is a more simplified, satin version. The black velvet hat, in particular, definitely has a substance to it, a gravitas to its construction. The other is much lighter, more delicate in the way it holds its form. In terms of construction, the simpler hat is striking for its delicacy – it’s ability to hold its inflated form. It speaks to his ingenuity in constructing this kind of hat. Then there are these beautiful scarves. We have a box of them. They are figure eight scarves, or propeller scarves, the form we discussed with the sculpture and are such a rich combination of colours.

Shortly after they met Charles James, the de Menils began building their house in Houston, in 1948 to 1950. Fairly early in the process, they brought in Charles James to help with the interiors. Dominique gave full credit to her husband. She said, ‘John, who was always full of extraordinary, creative ideas – dangerous ideas – thought of inviting Charles James.’ It’s interesting that they had this rigorous International-Style exterior and yet, for the interior, they wanted something more sensual.

John writes that their goal in bringing James into the house was this desire for fluidity. Dominique de Menil also talked about James being the antipode to the rectilinear line. The house could have felt very bare to them, a feeling of being exposed with these large, expansive windows. This wanting to soften the house, make it more liveable. This created the possibility of injecting the curvaceousness of James into the house and pairing it with the rectilinear. The meeting of those two sensibilities, and the capacity to hold them at once in a single space is remarkable.

What are some of the James contributions to the house that most stand out to you?

The first that becomes apparent is this idea of surprises. You go to open a cabinet, and the exterior is grey or pale blue, and the interior is an apple green or pale yellow. So, you have these wonderful moments of surprise that I think are some of the most fascinating interventions in the house. This isn’t something that a guest always sees; for example, many happen in Dominique de Menil’s dressing room, so they are very private. They are there for the pleasure of the inhabitant. The interior, like the day suit we were discussing earlier, has these very personal moments of pleasure and delight. For me, that is the crux of the intervention in the house: moments of delight that are often very personal.

For example, that chaise longue here in the living room. It is such a beautiful, dark form, and then, underneath is that very vivid yellow.

Yes, the fabric is grey, almost matching the grey wall, and then underneath is this very bright yellow, almost a lemon yellow. Again, a hidden surprise.

‘There is a fantasy that propels his mind forward – that seems to drive his innovation and makes him such a compelling figure in the history of fashion.’

This piece that we’re sitting on, this sofa, what have you learned about this?

The idea came from the Man Ray lips— it is variously called the ‘Lips Sofa’ or the ‘Butterfly Sofa.’ It was completed in 1952. From what I know, this was a trial to make. It was quite a process and was very expensive for its time. I don’t think the de Menils planned it costing as much as it did, but the trials and tribulations of executing the sofa impacted the cost. Getting the upholstery right was a challenge, and I don’t think James was ever satisfied. There was a lot of going back to the drawing board. It is a very complicated form, with all of these curves. When you look at the drawings for the sofa, you see how engineered it is, how much thought went into the curves. So it was arduous to execute. There are two others in the collection. In the exhibition, we will be showing one that is done in a sort of marine blue/ turquoise mohair velvet.

What do you know about the dressing room doors?

We have a wonderful paint card where he was mixing colours for reference, and you see the pale yellow in the middle which was very close to the pale yellow that ends up in the interior of the dressing room. But I like this idea of these very cool colours, very airy, the opposite of some of his other interventions in the home. For instance, in the main hallway, in the foyer, the colours are very rich and saturated and dark and moody and dramatic. But then when you get to her dressing room, it’s very airy and light and ephemeral feel- ing. I like that dichotomy.

It is fascinating to me how extensive his interventions were in the house. The furniture he designed, of course, and the dressing room, but then also the ceiling height, the dark grey wall, the antique piano, the dark floors, the velvets in the hallway, the Belter furniture, the 18th-century Venetian sofa and other historical elements – that’s a lot.

It is. For instance here, we are looking at the piano and grey wall and the chaise longue. The colour of the upholstery is close to the colour of the wall, and so you have this blending of surfaces with, on the underbelly of the chaise longue, this bright, unexpected pop of colour. You have this covering of surfaces in such a straight-forward linear house – almost at every turn, there is a James moment, so it really is quite extensive.

The richness of the fabrics at the windows…

Again, you have this play of lightness and airiness, transparency and sort of opaque. The green silk curtains there and their capacity to reflect light and their richness in contrast to these beautiful light grey cotton shears that allow in more light. These tensions play themselves out beautifully. This is just like a James dress here. I think of the concert gown that we have in our collection. It has an organdy white underskirt and this lush rich velvet and satin overskirt – these plays of richness and lightness. You see it played out in the house very well.

By the spring of 1950, as the house was being completed, James had already made four trips to Houston. Do you know very much about his time here in Texas?

I’m still on the hunt for more information. On his first trip down, he arrived with this huge green vase that he had bought at the Armory Show in New York. It was onerous – it was a trial even to get it to the house from the airport. But he arrived, and this was going to be his focal point of inspiration for the house. It’s this very tall green opaline vase, very extravagant, with gold detailing on it. He chose a bouquet of flowers for it, white lilies from California, that was to be his inspiration for the entire project. Another moment involved the piano over there on the grey wall. This was very important to him. He wanted a piano in the house. In order to get a sense of the space – how it was going to sit in the room, how it was going to feel in the room – he constructed a mock piano out of orange crates. After he left, the de Menils couldn’t find one of their suitcases. It turned out that he had built this mock piano around their piece of luggage. To me, that indicates his passion. He was so focused on his work that he buried their suitcase while dreaming up this piano.

In the last year of her life, 1997, Dominique de Menil was thinking about the idea of a Charles James exhibition.

The first mention of her desire goes back to 1995, in a biographical inter- view, when she said, ‘We must do a Charles James show.’ When the chaise longue is brought up, she says, ‘Yes, it’s incredible—it’s reversals.’ She was obviously sensitive to these plays James was making as a designer. Then, in 1997, close to her death in December, she was making notes. She recounted the story about how James came to do their interior and to tell the story of his life. Those are the only notes we have from her about the show. We might be doing it differently than she would have imagined but, considering how much Dominique and John believed in his work, I would like to think that it would have been gratifying to her.

Photograph courtesy of the Menil Collection