Curator Olivier Saillard on the Pasolini costume archives and their discreet influence on fashion.

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

Photographs by Astra Marina Cabras

Film by Brigitte Lacombe

Curator Olivier Saillard on the Pasolini costume archives and their discreet influence on fashion.

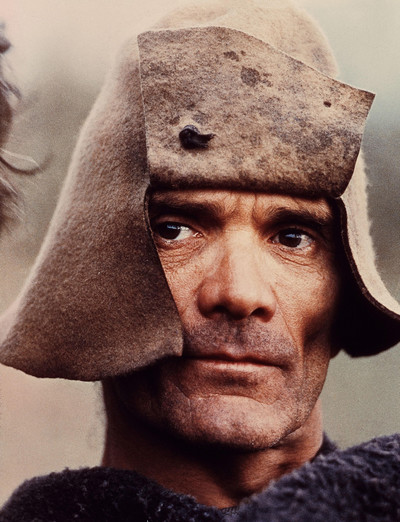

Pier Paolo Pasolini in The Decameron (1971). © Album/Alamy Stock Photo

Pier Paolo Pasolini in The Decameron (1971). © Album/Alamy Stock Photo

The exhibition Pier Paolo Pasolini. Tutto è santo (Everything is Sacred) marks the centenary of the Italian poet and film director’s birth. Currently presented at Rome’s Palazzo delle Esposizioni and curated by Clara Pamphili, the show brings together rarely seen documents, photographs, testimonies, letters and work archives about Pasolini. It also features a selection of costumes that were created for Pasolini’s films, selected by associate curator Olivier Saillard. Organized by the film in which they appeared and exhibited on hangers – just as they are in the archives of Sartoria Farani, the company that produced them under the direction of designer Danilo Donati – the costumes, worn by both leading roles and extras, reflect many of the visual and pictorial inspirations dear to Pasolini.

In June 2021 in Rome, Olivier Saillard, along with Tilda Swinton, staged Embodying Pasolini, which they recently brought to Paris in December 2022. The nearly two-hour performance, which also marked the tenth anniversary of Saillard and Swinton’s collaboration, saw the British actor wear a selection of 40 costumes from Pasolini’s films, ‘embodying’ and recontextualizing them into the present moment.

System sat down with Saillard to discuss the Roman trove of Pasolini costumes, their subtle influence on contemporary fashion, and the director’s idea of clothing as markers of who we are.

Thomas Lenthal: Just before we get into the work of Pasolini, I’m curious to know what it was that drew you towards costume design specifically?

Olivier Saillard: It’s the subject of performance that interests me. I was interested in seeing clothing that wasn’t attached to an era, or to a customer purchase, to consumerism, or indeed fashion.

I know that you’re passionate about workwear and traditional clothing, and in particular by the traces of life left by the wearer in an item of clothing.

These costumes are just as much work clothes! It is very hard to reuse an item of stage clothing when the actor is no longer present; it’s as though it has been abandoned. In Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew it really looks like the character spent his life in that costume. It’s a beautiful exercise in painting – certainly more painting than fashion – and especially with Pasolini, for whom colours were so important.

Were they well made?

No, not particularly. They are very simple. The big felt outfits are made like costumes for the theatre, held together with staples. I mean, it’s certainly not haute couture – they are made to stay together but not to last forever. That wasn’t the idea.

‘I was interested in seeing clothing that wasn’t attached to an era, or to a customer purchase, to consumerism, or indeed to fashion.’

For Visconti, costumes had to be very real for the actor. Burt Lancaster undoubtedly thought he was the Leopard, and needed underwear consistent with the era. Tucked away in the chest of drawers on set were shirts made especially for Lancaster, embroidered with the character’s monogram, that were obviously never seen in the film itself.

You’re right to point that out, because with Pasolini the actor often really had to feel the costume, but perhaps differently. They would be very aware of it. Those huge dresses in boiled wool were so heavy. They were really designed to give a ‘backbone’ to the actor, and to deny his or her belonging to the 20th century. Those clothes really weren’t the actor’s friends!

Does that draw any parallels for you with fashion?

Yes. When you wear Comme des Garçons, you are first and foremost in Comme des Garçons. It’s not always particularly ergonomic; it can be a bit hindering. You’re not simply yourself. When you’re a designer you ask yourself if you want the wearer to feel comfortable, natural – if you want them to forget what they are wearing. That’s not always the case with designers like Rei Kawakubo or Yohji [Yamamoto].

When you watch Pasolini’s films such as Oedipus Rex or The Gospel According to St. Matthew – the ones featuring those outsized hats – they are absolutely something you’d see at Yohji.

It’s funny, I like to think that the Japanese designers, Yohji and Rei, have watched Pasolini’s films. I also detect references to Pasolini in Alessandro Michele’s collections at Gucci, and in Pierpaolo’s at Valentino in the loose-fitting Ancient-style shape of the clothes and particularly in their decorative excess. The influence of Pasolini’s costume designer Danilo Donati was sometimes very clear in Lacroix, and you could also imagine that Margiela rummaged around in there, too. With him, there are all these photocopied images, and rough edges. Badly finished things have a sort of authority because the idea is worth more than the savoir-faire. That is quite a Pasolini notion. One could certainly draw parallels.

‘With Margiela, rough edges have a sort of authority because the idea is worth more than the savoir-faire. That’s quite a Pasolini notion.’

How did you end up getting involved with this Pasolini costume archive in the first place?

I was at a party in Florence, and I met Silvia Fendi who was with a lady called Clara Pamphili. I thought to myself, ‘Goodness, Pamphili in Rome – that’s a dynasty that dates back several centuries.’ I spoke to Clara, and she explained her family links, as well as her own ambassadorial role in Italian art and cinema and fashion, and I just said, ‘What I’d really like to see are the costumes from Pasolini’s films.’ I don’t know exactly why I said that because I hadn’t watched Pasolini’s films for a really long time. I had a bit of an idea in mind, just this sort of fetishism for Pasolini more than the costumes in particular. She replied, ‘Well there’s nothing simpler, because I’m one of the people who takes care of the archive.’ She connects a lot of people in Rome. She also works in schools; she’s a little bit involved all over the place – with designers, artists –and just happens to manage the Palazzo delle Esposizioni. So Clara took me to see the Pasolini costumes. I had no idea that they were all there.

Where are they kept? In a warehouse?

She took me to Sartoria Farani. It was a couture workshop for theatre where various costume designers including Danilo Donati made costumes. For about 20 years, Donati was pretty much the only one using the atelier, but then they started taking on other commissions. Besides this, there are warehouses, too, because for Arabian Nights alone, there are literally hundreds of costumes for all the extras.

Did Donati make the costumes for Pasolini’s period films at Farani?

Yes, always at Farani. All the costumes in the exhibition are by Sartoria Farani.

It is really well organized there?

I’m trying to help them to store things a bit better, so they get less damaged and are better protected. But they are arranged by film and are safe, so already that’s something. I mean, they would be better in a museum, but frankly there are just too many pieces for that to happen. You’d have to make an edit, but to be honest, no one dips into those costumes. The costumes for The Canterbury Tales weigh so much, like 20 kilos. According to Donati, every film had to have its own specific colour code and a fabric.

Amazing.

So for The Decameron it was felt. The Gospel According to St. Matthew was wool and boiled wool. The Canterbury Tales was incredibly heavy velvet – like 20 kilos, but it might have been nearer 30 kilos. It’s almost impossible to imagine how they moved in it. I have trouble imagining how that could be used in any other production.

It’s good to know that they are so well preserved.

I did ask them how come they were in such good condition, and they just said, ‘Well, no one ever asks to use them!’

I think Tirelli Costumi in Rome still rents out costumes, and you can see costumes from Visconti’s The Leopard being used in productions today. I wonder why Farani goes to all this effort to preserve an inheritance that, for them, has no economic value?

They do lend out costumes, just not those from Pasolini’s films. As I said, I don’t think many people ask for them. There is a sort of shadow ban against Pasolini, and people are scared of delving into that. Italy isn’t like France. There, he is still seen as a ‘communist pederast’, and especially at the moment, he isn’t well regarded. So all of his costumes are just floating around. They haven’t been given to museums or universities. It remains a very fragile legacy.

There’s no Pasolini Foundation?

Not a foundation as such. There is an estate; there are archives. Lots of things were given to libraries, but there’s no foundation. After Pasolini’s death in 1975, it was [actress] Laura Betti who took care of them, but she was said to be emotionally disturbed. She had a reputation for being dreadful to everyone, calling everyone a whore, a bastard.

Along the way in your research, have you met people who knew Pasolini?

Ninetto Davoli. He acted in several Pasolini films – La Ricotta, Arabian Nights and The Decameron. It was very nice spending time with him. He cried. He was Pasolini’s lover, I think, before he decided to get married, and Pasolini was very hurt by that. Ninetto doesn’t have dark hair any more, but it’s still curly and he still has an adolescent look about him. It was really very touching. He’s a very sunny sort of person.

You’ve mentioned Danilo Donati, who did the costumes for almost all of Pasolini’s films except Medea, which was Piero Tosi…

That was because Maria Callas was scared of Donati’s costumes! It was the first and only time she ever acted, and she was reassured by the presence of Tosi because he had already worked with her on stage at the opera. They did something very Visconti-esque, which wasn’t at all to the taste of Pasolini. So once Medea was finished, he went straight back to Donati.

When I watched Medea, I didn’t see any particularly radical change from Donati’s work. I actually think Tosi worked very respectfully within the world of Pasolini.

It’s true that it didn’t represent a major stylistic departure, but there was a sort of crudeness and a cruelty in the making of Donati’s costumes. It was very violent. He would rip the costumes up, he would knit them by hand, sometimes with no tools. He would dye them. It was a very wild way of undertaking costume design, which wasn’t at all how Tosi worked.

What do we know about this longstanding relationship between Pasolini and Donati? How did they meet?

They met on the film Mamma Roma, I think: Pasolini needed civilian clothes and Donati’s job was to find them. In interviews, Donati talked about what Pasolini would ask of him from one film to the next, and how he would then go off and just do his own thing. He would start from an initial point of reference, like Ancient Greece or Northern Africa, and then make costumes that looked more like they were based upon the Incas. But along the way, he would create what might be called a ‘universal feeling’ of the costume.

I was surprised and amused by the Japanese music in Oedipus Rex – I thought that was a brilliant idea.

Yes, exactly. The geographic, folkloric and traditional foundations are never clarified. For the costumes for this mythological legend, he draws from the Incas, and the music is Japanese. It’s like with The Gospel According to St. Matthew, which wasn’t filmed in the Holy Land.

It’s true. When I look at his period films, I feel that they’re consciously avoiding authenticity.

They aren’t reconstituted frescoes.

‘Clothes are like a self-contained social portrait. I think it’s fair to say that Pasolini was more interested in clothing’s social status than fashion.’

But they are nonetheless real.

Pasolini had a realistic vision. He would go to parts of Rome where the disadvantaged lived; people on the margins of society, living in the streets, persecuted. Go back to the novels he wrote and you find passages about clothes – particularly menswear – and their relationship to poverty. How what you were wearing could work against you and your aspiration, particularly if it looked neglected or worn out. Clothes are like a self-contained social portrait. I think it’s fair to say that Pasolini was more interested in clothing’s social status than fashion.

He certainly fetishized the image of the underclass.

Yes, he was keen to represent that, and show how the bourgeoisie, the rich, were often ridiculous. He saw the ‘little people’ as the victims of the other. For Mamma Roma, he went to thrift stores and found things that were connected to the characters. He wanted to make his own costumes, and I think that was a means to access his thoughts. For Arabian Nights, he used existing clothes. Making costumes is a way of escaping fashion, in fact. Avoiding fashion means the film doesn’t risk becoming dated. Of course, the films are dated by other things – the content and so on – but not by the costumes. Pasolini was an auteur, and this was part of his vocabulary, a vocabulary in motion to distribute his thoughts.

You’ve mentioned before to me that Oedipus Rex is the film that sent you down this path.

Yes, it’s my favourite. In Oedipus Rex, the colours are untamed. It’s full of cruelty. The clothes were knitted, and almost primitive. They don’t look very well researched, either historically or geographically. There are nuances of salmon colours, apart from Oedipus who is always in black, and Jocasta who is always in white. I don’t know, maybe because it’s the theme of the film, but I find the clothes really harrowing. But I’d still love to own a little dress from Oedipus Rex.

Are there lots of pieces from this film in the exhibition?

Yes, all of the Oedipus Rex pieces.

How did you choose the costumes for Embodying Pasolini, the performance with Tilda Swinton?

We took the clothes that we thought best embodied Pasolini. We took the costumes worn by the films’ stars, supporting actors, and extras – the most remarkable, the most lived in, the ones that most carry our memories. In fact, the performance deals with just that: how an item of clothing that’s been abandoned just after it was used can’t be something that feels lived in. How when costumes are no longer on an actor but on an almost transparent pedestal, a visitor can get close to the film. For the piece, we didn’t really go back to the films, but rather to what inspired the costumes. So, for example, we looked at frescoes by Giotto and gestures that had inspired the costumes, and by going back to that, rather than the films, we got much closer to their meaning.

How many costumes are there in total?

There is a selection of approximately 80 costumes for the performance. It lasts for two hours and is on a loop for four hours. It happens mainly in silence, apart from when there’s a little music that has nothing to do with the films – African music, and a piece by Chopin – and it’s very brief, coming from the pockets of the costumes, not speakers in the room itself. The clothes themselves remain humble. Working with costumes is much easier and much less dramatic than for clothing belonging to a dead historical figure. In the past, we’ve done performances using clothes that belonged to people like Sarah Bernhardt, Arletty or Napoleon. That was unsettling.

Yes, there was something ghostly about those performances.

You could really feel something. This Pasolini performance is really one of my favourites. I think it really succeeds in saying what is possible and what isn’t, and that these Pasolini costumes are monuments because we have decided that they are.