Privateness is possibly the most Venetian quality that the very Venetian jeweller Attilio Codognato possesses.

Text by Angelo Flaccavento

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Creative partner Dovile Drizyte

Privateness is possibly the most Venetian quality that the very Venetian jeweller Attilio Codognato possesses.

Years ago, Attilio Codognato was asked to open an exact replica of his Venetian store, Codognato, in New York. The Italian jewellery maker’s business was growing fast in the US, but Attilio declined: he felt neither the urge nor the will to take that direction. He was, and still is, a lover of emotions, and his best work is the fruit of a dialogue with his clients – both he and his customer have to be in the same room. It requires time to bond and connect.

Codognato has been a Venetian landmark since 1866, when Attilio’s great-grandfather Simeone opened the shop in the San Marco area. For over 160 years, the business has served royal families and the happy few, always keeping a strict shroud of discretion over its client list. Today, the gioielleria is still up and running, and still has just one point of sale in the world. There is no other way than heading to La Serenissima to get Attilio’s ghoulish, painterly creations – mostly skulls and snakes, but also mori, cameos and the occasional coffin as a pendant – or variations on the archaeological style the previous Attilio, grandfather to the current one, perfected at the end of the 19th century. Call it a sense of the genius loci or cultivating one’s own niche regardless of passing trends, fads, and geography. No openings in remote areas to cater potential markets. No wild dreams of expansion. Beauty, for Attilio, requires effort, as does his creative process. Codognato can only be a small-sized business.

‘For over 160 years, the business has served royal families and the happy few, always keeping a strict shroud of discretion over its client list.’

Attilio Codognato has built Codognato’s contemporary success. He gave the already admirable family heritage an unexpected baroque spin that is as personal as it is faithful to the irreverent sense of history that has always been part of the house’s spirit. In doing so, he has never actively looked for fame or clients. They came – and still come – to him, including the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Luchino Visconti, Maria Callas and Andy Warhol, who mentioned Codognato in his diaries. This privateness is possibly the most Venetian quality that this very Venetian man possesses.

Venice is a magnet. Suspended over glistening waters, always on the verge of sinking, it is still, fragile and powerful, a magical place where people go, attracted by its unique character and the cultural connections it creates. Venice is a door between the West and the East. As a city of merchants, it has carved its own identity out of the endless pillage of this and that, from here, there and everywhere. Its style is opulent and eclectic, and all the better for that. Venice is dark, mysterious, sultry, stinky, even. Minus the smell, it is also what lies at the heart of Codognato. Attilio’s willingness to stay where he is and to keep honouring Venice has never been nostalgic. He is not obsessed with the past or averse to change. Not at all. In fact, the gioielleria is changing address for the first time in its long history, from number 1295 Salizada S. Moise in San Marco to number 1316, just around the corner. It is still the same area, where all the luxury brands now flaunt their flagships, and which is now another five-star luxe open-air mall with the usual suspects and boutiques, like every big city around the world. The only difference is the magnificent Venetian backdrop. Codognato will possibly be the only shop in the neighbourhood with a local flavour, like the nearby Harry’s Bar or Caffè Florian. The plan is to make the new shop a replica of the old one.

‘One stays the same by changing,’ says Attilio, welcoming me into his home, a palazzo on the Grand Canal between Ca’ Pesaro and the San Stae church. Attilio, who is now 85 but still enjoys going to his shop every day, is taking a few months off. It’s October, the old shop closed in September and the new one should open in early December, right before the holiday season, when business flourishes. Attilio may be a gentleman, but he remains a merchant. His frame is small, making for a gently imposing presence, piercing eyes with a sense of the quixotic, a Roman nose made even more classical looking by his white beard, and backcombed white hair. He greets me wearing an immaculately pressed white shirt and black tailored trousers. Memory might trick me, but apart from a wristwatch, he wears no jewellery, certainly not the skulls that are his most sought-after artistic creations. Attilio is warm and welcoming, like the grandfather he is – his grandchild Andrea is pictured on these pages – with an inquisitive, at times slightly startled spark to his manner. As he speaks, one can hear a faint Venetian accent that adds another subtle layer of charm.

Attilio is definitely not one to scream for attention, neither personally nor professionally, yet he draws it, like the North Pole attracting a compass needle. It feels like he is a bundle of emotions, pressing against his proper, composed and gentlemanly persona, as if there is a whole trembling world behind the polite facade. One Attilio does not share with everyone. There is something secretive and private even to the way he utters his thoughts, talking in short, broken sentences, not fussing over details, leaving his interlocuters ample room for rumination. Attilio is like his jewels: you either like them or do not, understand them or not, and he is not going to make any effort to win you over. ‘Vedo che lei ha capito’ – I see you get it – he replies each time I try to enquire a little bit more. With a smile he tells me my questions are terrible, meaning that they are too inquisitive, and even intrusive. So I desist, defeated by Attilio’s unwillingness to go into details. This is not to say that our encounter is shallow; the way he looks at things, the objects that surround him, and most of all his starry-eyed silences are just as descriptive as words. Probably even more so.

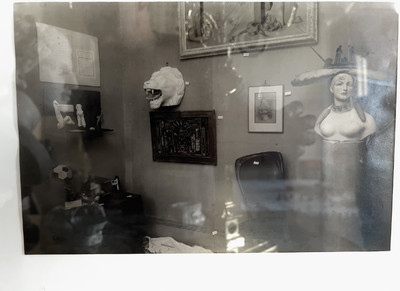

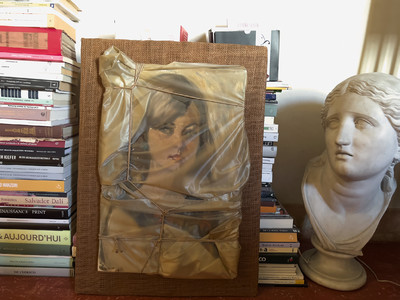

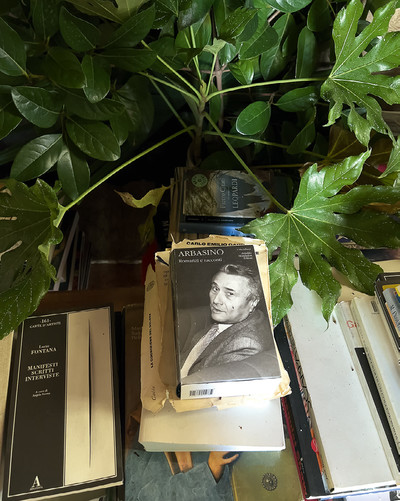

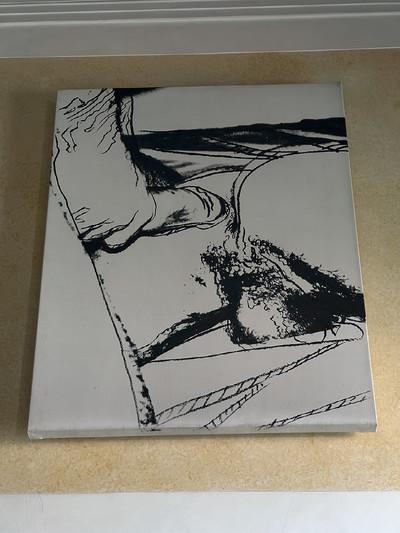

Detailed explanation, in any case, is overrated; it certainly is for Attilio. He reminds me of Venetian painting in a way. Traditionally, the scuola veneta was about shapes created with colour, whereas the scuola fiorentina – the Florentine school – was all about the precision of drawing as a base for everything that came on top of that. Venetian painters were the Impressionists of their time, so to speak. Attilio, too, is about hazy definition, and he invites you to get close in penombra, in the half-light of the palazzo with its typically Venetian varnish of decay and collection of wonderful contemporary art, scattered around without a hint of preciousness. As I enter the main room, I am greeted by a magnificent Robert Morris sliced piece of felt, which is mirrored by another one on the opposite wall. The room is typical of historic houses in Venice; it is like a ballroom of sorts that gives onto all the rooms of the house. Other artworks on display include pieces by Gilbert and George, Jannis Kounellis, Joseph Kosuth, Marcel Duchamp, Robert Rauschenberg’s cardboard boxes and rope, and a door by James Rosenquist. Throughout the house, contemporary art is mixed with antique pieces and Empire-style furnishing.

Art is Attilio’s big passion besides jewellery. ‘These pieces are like my babies – i miei bambini,’ he says as we wander around the room. He considers art an emotional, not a financial investment. ‘This collection was born at the same time of the jewels,’ he says, ‘and in some ways it is identical to them.’ The further you delve into Attilio’s world, the more you perceive it as suffused with and tightly wrapped in a halo of (dark) romance. What becomes most striking about the man, his life and habits, and his exceptional oeuvre is that it all comes together as a whole. The many facets of Attilio – the man, the jeweller, the refined art collector – are all expressions of him, through different means. And what lies beneath this organic expression of self is essentially his singular taste, nurtured by a cosmopolitan life and upbringing with firm Venetian roots. It has led him to create his own creative universe, including art that often belongs to the dimly lit, obscure periphery of an artist’s oeuvre. Taste, of course, is something intangible, the portrait and expression of a person told through objects, choices, and selections. Attilio is a man of taste.

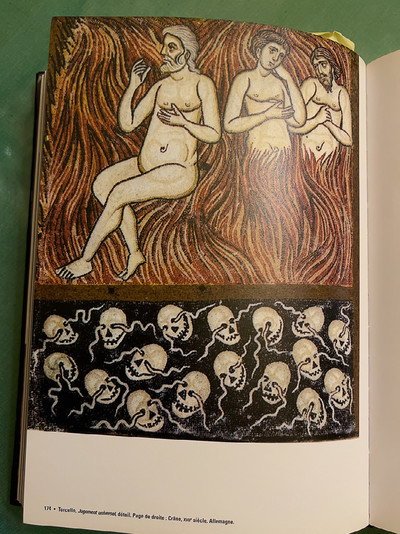

Attilio Codognato’s taste for darkness is a paradoxical version, more vital rather than gloomy, forceful rather than sombre. Attilio has forged his own iconography drawing inspiration from centuries of art and existential musings on the transient quality of human life, condensing them into something as decorative and glitzy, but also as permanent, as jewels. The skulls he is renowned for, in fact, have a painterly origin: the memento mori and vanitas paintings that reached a peak with the Caravaggian school in the early 17th century. These compositions were seemingly dull masses of fruit, flowers and tableware, but in fact, bore deep existential meanings and intricate allegories. Just like the brooches, rings, pendants and earrings that bear Attilio’s skulls, eyes glistening with colourful stones. They are an ode to life, rather than a warning of death. They carry the certitude that life is short, and the end is inevitable, but in ways that suggest awareness, not pessimism. They are jewels, after all. They are meant to shine and be beautiful.

‘The brooches, rings, pendants and earrings that bear Attilio’s skulls – eyes glistening with colourful stones – are an ode to life, rather than a warning of death.’

The iconography of skulls, and the historical connections it evokes, ultimately expresses Attilio’s personal bond with history, both his family’s and the history of art and Venice. ‘I did not invent the skulls,’ Attilio says, enigmatically. ‘In a way they were already in my father’s work.’ Attilio learned the craft from his father and the artisans he worked with, while discovering a passion for art with a collector uncle, Enrico Hintermann. He calls Fabergé and Kenneth Snowman maestri, and has a fondness for Marcel Duchamp. His knowledge of history is wide. What sets him apart, however, and what makes Codognato a business that cannot grow in numbers, but only in depth, is his willingness to connect with the client, to keep it real, making it all about the object, not about codes, numbers or communication.

‘In the end, what I look for is the emotion of an encounter,’ he says. ‘I have no favourite shapes or stones, because my best work is the result of a dialogue with a person, nothing more than that.’ By this time, we have moved to the dining room, where lunch is served. As I contemplate a splendid Cy Twombly on the wall – a bunch of hasty black scribbles around a thick lump of white – I am musing on the artist’s ability to unlearn his craft and paint like a child. ‘Or paint like a man leaving messages on the wall in the public restrooms,’ says Attilio, with a glint in his eye and a grin, his sardonic sense of humour bursting out.

As the bearer of a family knowledge that has been passed on from one generation to the next, to use his words, ‘by osmosis’, he lives with the feeling of history endlessly repeating itself. ‘It’s like pages of the same book,’ he says, ‘they are all the same, and yet they are all different.’ There is no designated heir apparent to the gioielleria for the moment. Attilio’s children are not directly involved – Mario is a famed curator, Cristina a psychotherapist living in London – but Attilio is not worried. Fatalism is a quality all islanders possess, and Attilio is an island in the jewellery world on the island that is Venice. ‘Codognato will be around for a long time,’ he says, adamantly, and settles into a long, affirmative silence.

Post-production by Lucas Rios Palazesi at QuickFix.