In a rare interview to mark his eponymous brand’s 30th anniversary, Junya Watanabe reflects on nostalgia, the avant-garde, and his own sense of enigma.

Text by Alexander Fury

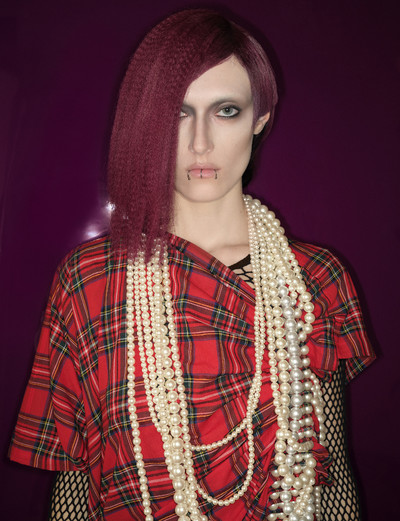

Photographs by Johnny Dufort

Creative direction by Junya Watanabe

In a rare interview to mark his eponymous brand’s 30th anniversary, Junya Watanabe reflects on nostalgia, the avant-garde, and his own sense of enigma.

Over time, it has become painfully evident that Junya Watanabe does not like to be interviewed. That’s not a snipe, merely a statement of fact. There is scant information available on his life or first-person explanations of his work, despite last year marking the 30th anniversary of his eponymous brand, and 2023 the same anniversary of his first fashion show in Paris. Interview requests tend to be politely rebuffed by the press office at Comme des Garçons, the company that owns his brand, and even when granted, Watanabe can be outright evasive in his answers. You’ll ask a question and Watanabe will answer it differently to how you might expect, even diffidently, sometimes dissidently. Basically, exactly how he pleases.

Interviewing Watanabe in episodic emails, in the weeks leading up to and immediately after his Spring/Summer 2023 show, which took place on October 1 in Paris, gave our exchange an even stranger cadence. There is, of course, the definite quality inherent to written correspondence, a lack of interpretation or inference, but our back and forth was also subject to translation, of course. My questions became verbose in a vainglorious attempt to round out and encourage longer answers, which perhaps the medium inherently discourages.

Nevertheless, the ongoing correspondence allowed for the possibility of returning to ideas and themes that seem to excite interaction or, doggedly, to try and extract more precise answers from this relentlessly taciturn interviewee. Who doesn’t like a challenge?

Fri, Sep 16, 2022, 11:30 AM BST UTC + 1

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

This year marks the 30th anniversary of your label. Does that milestone mean anything to you – does it hold a significance at all? Has it influenced the way you are creating this year?

Wed, Sep 21, 2022, 8:41 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

It does not mean anything specific to me.

Wed, Sep 28, 2022, 6:07 PM CET UTC + 2

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

What are your views on populism versus elitism? Not just in fashion, but in culture as a whole?

Tue, Oct 11, 2022, 8:05 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

I think that this topic should be considered either by media or academic people. I do not want to speak about such a topic in public.

Wed, Sep 28, 2022, 6:07 PM CET UTC + 2

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

What is your feeling about becoming a ‘star’ to many young people – and some older ones, too? You are one of fashion’s rock stars. Your name is even the title of a rap song. How do you feel about celebrity, about the fact your name and, perhaps, face, are known? Do you feel a degree of celebrity at all? I am always interested in how this affects designers, as so many are shy and reticent figures who wish to focus on their work rather than on the cult of personality that has been built around them. I find it interesting to ask you this, honestly, because it does not seem as if it is something you would be naturally drawn to or embrace. Is there a tension between achieving your goals – between success, expressing your ideas to the world – and the somewhat unwanted consequences? Does it affect your daily life?

Tue, Oct 11, 2022, 8:05 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

I am not a celebrity. Since I keep my relationships with people to the minimum, there is no influence on my daily life.

To say that Watanabe fiercely guards his privacy is a profound understatement. The vacuum of information around him is ample demonstration of that. It is not the theatrical absence of Martin Margiela, Garbo-esque in its inscrutability, which has by now created a cult of personality as powerful as any around omnipotent designers such as Karl Lagerfeld. The artist is present – you can say hello to Watanabe after a fashion show, although he will not have bowed at its finale – but he absents himself from anything further.

Watanabe’s silence reminds me of times I’ve interviewed artists, many of whom are more willing to write down their thoughts than say them aloud and – like Watanabe – would simply prefer that their work speaks for itself. We often espouse the idea that fashion is and always has been a powerful mode of communication, and with its seductive imagery now harnessed to the egalitarianism of the internet, its messages have become particularly potent. Yet the fashion media too often strong-arms designers not only into speaking about the meaning behind what they create, but also explaining for fear that something might be lost in the translation from image to words. ‘Sometimes, I would like a little more feedback,’ Watanabe told American Vogue’s Sarah Mower in 2006. ‘Criticism would be better than silence.’ But how can people critique if they don’t understand? There is also often a fear of misinterpretation of meaning, especially when clothes are abstract and removed from received notions and accepted stereotypes, when they no longer hew close to our preconceptions of how a broad, padded shoulder symbolizes power, a spreading skirt below a wasped waist femininity. Because Junya Watanabe refuses an easy explanation, we are forced to analyse.

I should emphasize that there seems no truculence to Watanabe’s reluctance to speak – he seems genuinely nonplussed as to why people may be curious about his views, his inspirations, his working methodology. Possibly because he doesn’t share that feeling of inquisitiveness. ‘When I buy music,’ Watanabe once told me. ‘I don’t care about where the musician came from or his background or what his intent was. I just listen to the music, and if I like it, I like it.’

Yet people, including myself, are curious – because Junya Watanabe, now aged 61, is one of the great fashion designers of our time. It was recognized early: 21 years ago, the Victoria and Albert Museum featured Junya Watanabe’s work heavily in an exhibition fittingly titled Radical Fashion – because that’s what Watanabe has always made. His radicalism takes on many forms, as his clothes do when they twist around the body in unforeseen and unforgettable shapes that remap the topography of known anatomy. He has also innovated through techniques, basing extraordinary collections around seemingly humdrum techniques like pleating or water-resistant fabrics, which he demonstrated for Spring/Summer 2000 by deluging models with a sudden interlude of inclement weather mid-catwalk, like a pipe had burst overhead, allowing a delighted audience to watch the drops bounce off his clothes.

Sometimes, Watanabe’s clothes are even radical in their banality – in his work, there is often a compelling notion of examining the quotidian and rendering it alien, of radically morphing the acknowledged and understood. Watanabe has reworked wardrobe staples like trench-coats and denim, army fatigues or sailor stripes, down jackets and leather biker jackets. They never become unrecognizable, but they do become other.

Thu, Sep 1, 2:34 PM BST UTC + 1

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

I don’t want to pry too much, but as this piece will be published after your show in October, I thought it would be good to speak, even abstractly, about your state of mind at the moment. What are you thinking about and considering that may be reflected in this forthcoming show?

Thu, Sep 8, 2022, 10:00 AM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

I think about my approach to creating garments and my way of expressing the collection separately. While the garments are taking shape, it is still a process of trial and error about how to present the collection. Continuing the previous men’s collection, I am interested in how to make familiar things look new and fresh; I am still reflecting on this.

Fri, Sep 16, 2022, 11:30 AM BST UTC + 1

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

In our last correspondence you declared an interest in making familiar things look new and fresh. So many designers are fixated with the idea of the ‘new’ – what is your response to that, does it interest you? What are your feelings on innovation? Is it something you actively seek?

Wed, Sep 21, 2022, 8:41 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

I want to design something innovative, something that no one has ever seen before, something that will even change someone’s life and mindset. There have been such designers in the past and I believe there will be some in the future as well, but I am not a creator like them. That is why I always strive to get closer to them. I feel that such creations do not come out easily but rather suddenly through a lot of trials and errors. However, for the current mood of my creation, I am interested in the idea of reconstructing authentic items such as the motorcycle jacket, tailored jacket and trench coat into something with a new value.

Thu, Sep 1, 2:34 PM BST UTC + 1

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

Has your approach to design shifted over the past three decades? Or do you create clothes for the same reason and with the same set of goals and ideals as when you began? Furthermore, what are those goals? What do you want your clothes to express, to evoke?

Wed, Sep 28, 2022, 6:07 PM CET UTC + 2

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

Many would say that you have achieved your stated goal, that you have created something innovative, that no one had seen before. I understand though that, often, it is difficult for designers to be satisfied with their own work, with their own creations. You, like so many creative people, always strive for better. But I do wonder if you have been especially proud of any particular collections, if that’s the correct word? Perhaps satisfied with? Are there shows from your own past that you feel approach that goal you set for yourself?

Tue, Oct 11, 2022, 8:05 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

As I mentioned before, I do not have any feeling of accomplishment about my creations. Although I do not deny my past works, I am not proud of them either.

Otaku is an interesting Japanese word. Roughly and indirectly translated as ‘geek’ or ‘nerd’, it denotes an obsessive interest in something niche, often applied to fans of anime or manga. In the past, it was used to describe interests so intense it rendered people unable to function in society, but now it has mellowed and come to mean deep passion. There’s a touch of otaku to Watanabe’s work, in his relentless pulling apart of clothes, his investigation of their forms and reconfiguration of both their shapes and meanings. Indeed, so exhaustive have his obsessive examinations of clothing archetypes and construction methods proven that they have become inescapable points of reference for fashion as a whole. If a designer wants to create a biker jacket, they have to examine Watanabe’s versions. The feeling isn’t mutual. ‘I don’t really look at the other designers,’ he says, ‘I don’t really know what they’re doing. I don’t intentionally try to do something different. Instead of trying to create something alternative, it’s really an expression of what I really, really want to create. It may seem alternative to the audience, but for me, it’s my own way, what I really want to show.’

In doing so, Watanabe has somehow managed to transform garments previously considered static – MA-1 bomber jackets, those motorcycle leathers, pleated skirts, white shirts, T-shirts – and in doing so, reinvented many fashion wheels. It is an exceptional achievement. He is one of the rare designers whose clothes confound expectations, whose inspirations can sometimes confuse. Confusion can be good. It means something is new, which is what Watanabe is interested in. ‘I feel that the word “new” is such a hard word to define and to grasp, and understand,’ says Watanabe. ‘I always try to work towards creating something new, achieving something new.’

That notion of the new is a persistent thread running throughout Watanabe’s work, sometimes even woven into it. In 1995, he presented a series of clothes in a stain-proof fabric woven from polyester and steel devised by a manufacturer specialized in fibres used in radar equipment. In 1999, he worked with Japanese textile mill Toray – which invented Ultrasuede in the 1970s – to create a waterproof textile that traps air and pushes water to the surface, rather than repelling liquid with an impermeable coating. It was the fabric he used for that Spring/Summer 2000 collection. His style oscillates, constantly, between the innately accessible and opaquely esoteric. You genuinely never know what you will see each season at a Watanabe show.

Wed, Sep 28, 2022, 6:07 PM CET UTC + 2

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

Did you feel a connection to fashion, as a child or an adolescent? What originally drew you to the fashion world?

Tue, Oct 11, 2022, 8:05 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

I was not interested in fashion in my adolescence; I was instead a boy who was purely obsessed with music. I became interested in fashion when I started thinking about my future occupation. I am not a fashionable person. My first step into the fashion world was when I became interested in Issey Miyake’s clothes while searching for a job that would allow me to express my ideas in some way.

Thu, Oct 20, 2022, 5:50 PM AST, UTC +3

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

You mentioned your aim to innovate, to create something that no one has seen before, something that will even change someone’s life and mindset. Which designers do you feel have achieved this, in the past? I am, perhaps, covertly asking you to tell me which designers you admire, and why you admire them. I am intrigued as to whose work you strive to approach with your own.

Wed, Oct 26, 2022, 7:10 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

I feel that the works of our president, Rei Kawakubo, and Issey Miyake have had tremendous impacts on the world, not only in terms of clothing, but also in terms of social phenomena and artistic aspects.

Little information about Watanabe’s upbringing is available. The designer himself is as reticent to talk about it – of course – as he is about so much else. He was born in 1961 in the city of Fukushima. You ask about influences in his childhood, about his parents, about how and if fashion registered, and Watanabe pushes back. ‘Nobody had a creative profession in my family,’ he says. Yet his mother had a shop offering made-to-order clothes. In case that sounds too grand, Watanabe clarifies that his mother was a seamstress rather than a designer, selling ready-to-wear that she tailored to fit client’s bodies. First hearing that, I couldn’t help but think of the pinching and folding that so often characterizes her son’s work, his approach so like a dressmaker fitting garments to a body. He doesn’t speak about his father.

In 2016, I travelled to Tokyo to interview Watanabe in person, an exceptional experience. It was in August, the humidity an oppressive 70% or so. I landed as Typhoon Mindulle was coming ashore, buffeting the bamboo that lines sections of the highways leading from Narita Airport to central Tokyo. Taxis there are blocky, vintage models, archaic-looking Toyota Comforts or Nissan Crews; the drivers wear crisp white gloves, the interiors are outfitted with lacy covers to protect their seats like a stereotypical grandmother’s house. All of this seemed quaintly at odds with the avant-garde fashion that has become so synonymous with the country.

The Comme des Garçons companies – including the original label and its menswear line Homme Plus, the Tao line helmed by Tao Kurihara, the label Noir Kei Ninomiya, established in 2012, and of course Watanabe’s men’s and women’s labels – are responsible for much of that repute. They are based in a brick office building in Aoyama, and have been since 1982, the year Kawakubo first gained notoriety and pre-eminence by showing a collection of hole-pocked black clothes in Paris. Her designs, and those by her then romantic partner, Yohji Yamamoto, were dubbed, among other epithets, ‘Hiroshima’s Revenge’ by a casually racist fashion press. It was an attitude based, in part, on a fear of clothes that literally and figuratively clawed at tradition and poked holes in received ideas of dress. Instead of being tailored, clothes were cut flat, seemingly baggy and shapeless but actually focusing on a different relationship between body and cloth. Kawakubo’s early shops even eschewed mirrors in their fitting rooms: she wanted customers to focus on how clothes felt rather than how they looked.

The label’s collections exerted a significant influence upon a young Watanabe. ‘During my studies, Rei Kawakubo, Yohji Yamamoto, they were the big names,’ Watanabe says. ‘I studied them, and of course I was influenced by them as well. At the time, I was very influenced by Pierre Cardin, too.’ At that point, Cardin was a fuddy-duddy fashion dictator best known for owning Maxim’s and licensing his name to everything from floor tiles to sardines to orthopaedic mattresses. Yet there’s something of Cardin’s early innovation in Watanabe’s striking, uncompromising shapes, his obsession with geometric forms, his interest in innovative materials, that aforementioned ceaseless search for the new. It was something he found in the work of Issey Miyake, too, whose influence he describes as ‘profound’. Like Cardin, Miyake played with fabric and form, pushing the limits of both.

Wed, Sep 28, 2022, 6:07 PM CET UTC + 2

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

Do you ever look back at your own work? Is there a sense of self-examination at all or are you always anxious to move to the new and the next, to push yourself towards the future?

Tue, Oct 11, 2022, 8:05 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

I sometimes look back at my past works and use them as a reference during the creation process. I think it is impossible to come up with an idea from nothing.

Wed, Sep 28, 2022, 6:07 PM CET UTC + 2

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

Given the general tone of these questions, I wanted to ask how you feel about nostalgia? It seems today to be all-pervasive, with referencing abounding among the work of many designers, as well as figures from other cultural spheres. Have you ever been seduced by nostalgia? And if not, why not? Conversely, is there anything you are nostalgic about – even if you wouldn’t address it through your work, perhaps?

Tue, Oct 11, 2022, 8:05 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

As it might be commonly said, I’ve turned 60 and I think that I feel nostalgic about the past more often. At the same time, I have also been feeling strongly that past experiences make the present. While I can distinguish nostalgia based on personal emotion from nostalgia I can feel in my work, it is true that nostalgia still exists at the deepest level of this collection’s theme.

I had anticipated the Comme des Garçons building would be stark and severe or perhaps slightly chaotic and guerrilla in the vein of the Dover Street Market spaces. In reality, it just looks like some anyplace office building, the architecture of its design studios similar to many others, too. Watanabe has never left this building, professionally speaking. He joined Comme des Garçons in 1984, straight after his graduation from Tokyo’s Bunka Fashion School. He rapidly became head of Comme des Garçons’ Tricot and menswear labels, before the company created a womenswear line especially for him, under his own name, in 1992.

Designing under the same roof, comparisons between Watanabe and Kawakubo are inevitable – and, spanning the entirety of his working life, Comme des Garçons has fundamentally shaped his design ethos. ‘During my studies I would create clothes based on the textbook of how to make a dress, how to make a jacket, step by step,’ he says. ‘Those ideas were completely thrown out the window when I came to the company. You may already know, but when I entered the company, even the street styles and street fashion was completely different from what Rei Kawakubo was creating. That had a great impact on me as well.’

Kawakubo’s early work and its layers and deliberately abstract loose silhouettes challenged conventional Western dress – the kind of garments Watanabe’s mother fitted to the physiques of her Japanese clients. Kawakubo’s recent work has been described by the designer herself as ‘objects for the body’, constructing shapes in cloth that question the permutations and limitations of what we can describe as clothes. Yet, interestingly, Watanabe has in some respects gone in the other direction, with his explorations of staple garments, and embrace of traditions and investigating archetypes. Unlike Kawakubo, he has created collections with fit-and-flare silhouettes reminiscent of Dior’s New Look and homages to Gabrielle Chanel’s Waspy 1960s bouclé tweeds.

As part of my visit to Watanabe, and after much back and forth, I wrangled the opportunity for a walk-through of Watanabe’s ateliers. He wasn’t especially pleased about it, but eventually consented. When I passed through the door into the deserted room, I realized that every single garment, every mood board, every bolt of fabric had been completely covered, with an obstinacy so extraordinary I almost laughed aloud.

Watanabe will explain his clothes in few words – if you’re lucky, there may be a whole sentence, but it’s a rare occurrence. Here are a bunch of his gnomic pronouncements. ‘Geometric sculpture.’ ‘Heavy-duty couture.’ ‘Hyper-construction dress’ (paradoxically, another was labelled ‘Non-constructed’). ‘Sexy by Junya Watanabe.’ A few times he has simply stated there was no theme. It reminded me of something the milliner Stephen Jones once told me about working with Rei Kawakubo. As inspiration for the hats he was to make for her collections, she would him fax ideas, sentences, maybe a drawing if he was lucky. On more than one occasion, he said, she sent the simple statement, ‘I don’t know.’ Kawakubo works the same way with her design staff – and Watanabe began as a pattern-cutter alongside her. To those cutters, she briefs in abstract, invites accidents and interpretation; Watanabe does the same with his staff. ‘“What intrigues you?” is the question I ask the pattern makers,’ says Watanabe. ‘What each individual thinks is interesting – something that’s completely unrelated to the idea of clothing.’

Fri, Sep 16, 2022, 11:30 AM BST UTC + 1

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

Music seems a particular source of inspiration. You’ve created collections inspired by Debbie Harry, and last Autumn/Winter you titled your show Immortal Rock Spirit. What is it about music that inspires you? Is there something in its universal connection, its emotional resonance for so many people, that you find attractive?

Wed, Sep 21, 2022, 8:41 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

Yes, you are right. Music that remains in my memory or which I was obsessed with listening to when I was young still fascinates me and I have featured it as a theme of runway shows several times. For me, music is more about personal taste and memories, than the fact that it has universal connection and resonates with many people.

Sun, Oct 16, 2022, 11:29 AM BST UTC + 1

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

Could we possibly talk a little about your design process? Is there a great deal of physical work with patterns and fabric, with manipulating cloth? Or do you work more conceptually? Do you have a large team to help?

Wed, Oct 19, 2022, 9:52 AM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

For all of the garments, we try to reach the form by manipulating fabric. A lot of forms and details without concept end up creating a concept. Our team consists of more or less ten pattern-makers and ten working on the production. We produce the garments in approximately ten factories in Japan.

Sun, Oct 16, 2022, 11:29 AM BST UTC + 1

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

Your Spring/Summer 2023 collection framed your work within the New Romantic subculture – but it also felt like an exercise in pattern-cutting, with clothes almost embedded inside free-falling cloth. Did the inspiration for those pieces come from the New Romantics or from another idea? I wonder how it all links together for you in this specific collection?

Wed, Oct 19, 2022, 9:52 AM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

The concept for the Spring/Summer 2023 collection was ‘one piece of cloth’ and ‘reconstruction of uniforms’. As you realized, I started with the idea of whether we could make garments by embedding necessary structural parts such as shoulder padding and hair canvas, into an uncut piece of cloth to constitute garments. Reconstructing uniforms, as another concept of clothes-making, is one of the techniques I use every time. This time, we deconstructed and reconstructed racing wear by Komine, which is a Japanese motorbike-wear company. There is no specific reason why I chose racing wear; it was simply the uniform that I felt like reconstructing. In other words, the uniform inspired us to create garments; New Romantic is just a concept for the show stage. I came to it while I was thinking how I could present the garments that were born from the idea of exploring form and fabric in an exciting and an interesting way. Regarding this consideration of New Romantics, there was an extended sense that lasted from the pop culture of the men’s collection in June. In terms of music history, the men’s collection was American, but this women’s collection is about London in the similar period. I also had a nostalgic feeling. Although it is great to move forward innovatively and be avant-garde, the current situation did not make me feel like that in many ways. If I take an example of music, it might be like a classical musician playing with a contemporary mindset by considering the works of great composers in the past.

Watanabe no longer cuts his own patterns. ‘While I no longer make patterns myself, the instructions I give to our cutters are based on my knowledge of pattern-making,’ he says. Watanabe’s past is traced in every seam, his knowledge in their placement and intention. They scar jackets with unexpected cuts, complex and intricate, or converge at a waist, suppression and expansion allowing fabric to flow. There is an early Watanabe collection, from 1996, in which the cut of the dresses seemed to carve them away from the body at the back, like aprons worn over trousers. Another collection, two years later, presented clothes sewn from folded panes of fabric, their volume achieved by the insertion of twisting loops of thin metal tubing inside narrow channels that buoyed the clothes out, sometimes helter-skeltering around the outside like abstract jewellery. There’s a more universal past, too, a notion of memory and history built into many of Watanabe’s pieces. A fan of seaming at the waist may recall the pinched-in waists of 18th-century gowns; those metal rings look like 19th-century crinoline hoops.

If Watanabe’s collections perhaps remained in the abstract for the first decade or so, in more recent work, his love of music has been more assertively expressed. You might even hypothesize that when Watanabe creates collections themed around fashion, they seem like work; when they are themed around music, they feel like fun. The most mind-boggling collections he has executed have been obsessive explorations of crafts like pleating or garment typologies; the most enjoyable shows he has staged have seemed like odes to musicians he particularly admires. In March 1996, he showed an Autumn/Winter collection nearly entirely composed of black leather on models with close-cropped hair and tattoos painted down their arms, all set to the screeching guitar riff of Jimi Hendrix’s version of ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’. Other shows have dressed models as avatars of Blondie’s Debbie Harry or in chopped-up band T-shirts patchworked into dresses and coats.

This Spring/Summer 2023 collection was obviously another example. It was held at the Palais de Chaillot, not in the grand chamber sentineled by a panorama of windows overlooking a picture-perfect view of the Eiffel Tower, but in a space used by most designers for their backstage. It was a typically Watanabe touch. The models strode around to live-mixed music, a mash-up of Duran Duran, Cabaret Voltaire and Japan (the band), hairstyles and make-up flashing back to the early 1980s. The audience bounced in their seats, enthused.

If Watanabe talks about the importance of the reconstruction of uniform – and his Spring/Summer 2023 collection alone took in a litany, from city suiting to motorcycle clothing to bourgeois uniforms of prim blouses with lariats of pearls – the garb of youth cults and musical fandom can be seen as another type of unofficial uniform, one equally embedded with meaning in the tiniest gestures. Watanabe’s work has always toyed with those gestures and symbolism, using the implied meaning of certain fabrics, cuts and details to discover a new language of clothes.

Thu, Sep 1, 2:34 PM BST UTC + 1

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

The last two years of the Covid-19 pandemic have been exceptional times for us all to live through. Your first show in Paris for over two years was in June and felt like a light at the end of a tunnel. What has this period been like for you? Has it affected how you create, and what you create? Which lessons did you draw from the experience?

Thu, Sep 8, 2022, 10:00 AM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

In terms of monozukuri – creation – nothing has changed because of the Covid-19 pandemic. My monozukuri is a repetitive process, of working in my head, and with my hands, in a room.

Thu, Oct 20, 2022, 5:50 PM AST, UTC +3

Alexander Fury <_______________>肥後拽恨:

You’ve alluded to the current state of the world. How has that affected you creatively? Does the uncertainty of our current moment – war, the economy, the pandemic – make you feel, perhaps, more nostalgic? Is it about comfort during difficult times? Is now a difficult time to move forwards?

Wed, Oct 26, 2022, 7:10 PM JST UTC +9

Junya Watanabe <_______________> wrote:

In my previous answer, I did not mean ‘the current situation in the world’, but rather my personal situation. As a person living in the society nowadays, no matter your standpoint, you are moving forward while being affected by something, aren’t you?

The focus here has been womenswear, because while Watanabe has a successful and influential menswear business, which he has shown in Paris since 2002, he says he approaches creating for the two lines differently. ‘For menswear, I take an approach to creating garments that I could have in my wardrobe,’ he writes, in one of our exchanges. ‘For womenswear, I am not creating for someone’s wardrobe; rather I would say it is purely a laboratory of my creation.’

I wanted to return to something Watanabe said, about his fundamental wish in creating clothing: he wants to change people’s lives. This, I suspect, is difficult through fashion, and always has been. Yet what Watanabe has, perhaps, been able to do is shift a mindset. He has altered the way the world – or, at least, some of it – looks at things. He has questioned conventions previously considered immutable, and turned them on their head. He has embraced fashion clichés, exploded them, even destroyed them. That’s his legacy. That’s what is truly new.

Models: Ash at Girl, Birgit at 16 Paris, Emily at First Model Management, Juliette at 16 Paris, Lera at Studio Paris, Mika at Metropolitan, Teo at Success, Timothé at M Management.

Hair: Eugene Souleiman.

Make-up: Isamaya Ffrench.

Post-production: IMGN.