For designer Martine Rose – and her best friend and stylist Tamara Rothstein – inspiration comes from lived experiences, not moodboards.

Interview by Murray Healy

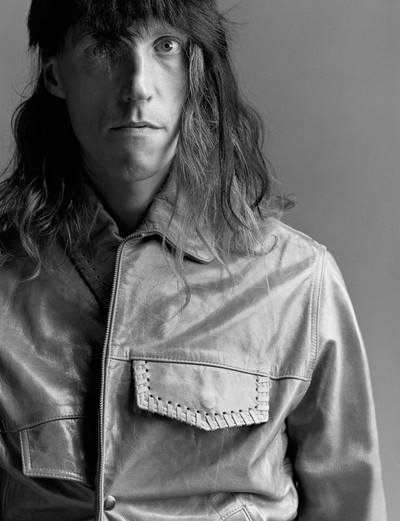

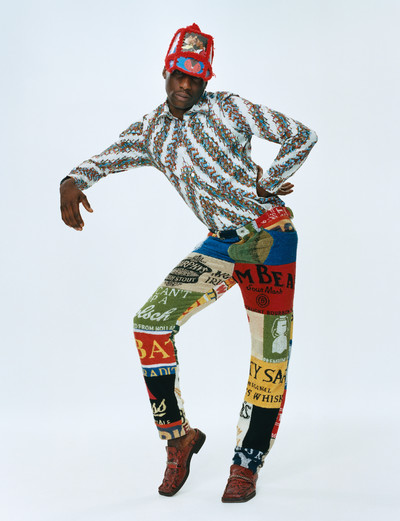

Photographs by Oliver Hadlee Pearch

Styling by Tamara Rothstein

For designer Martine Rose – and her best friend and stylist Tamara Rothstein – inspiration comes from lived experiences, not moodboards.

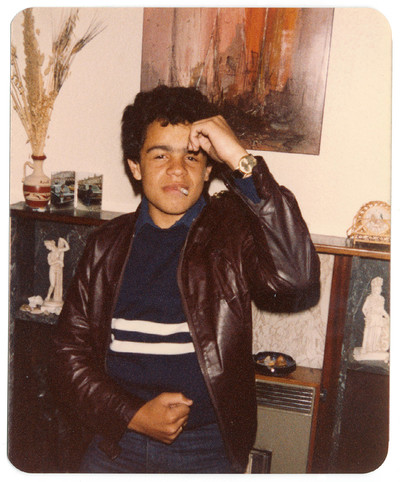

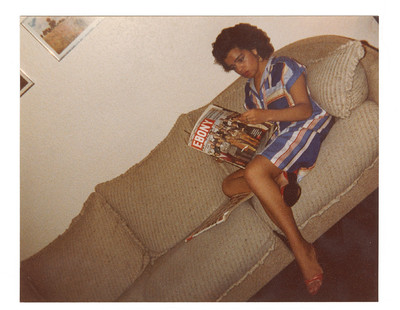

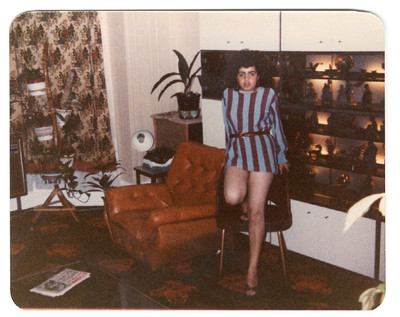

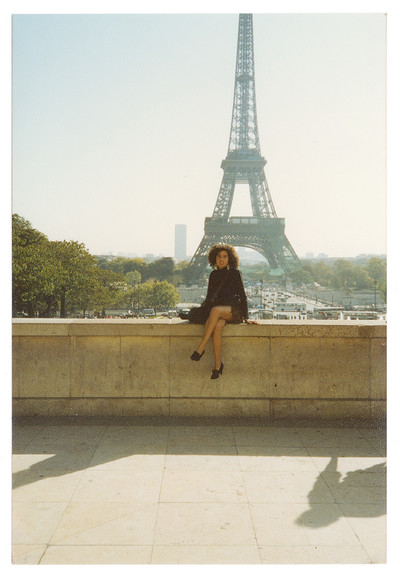

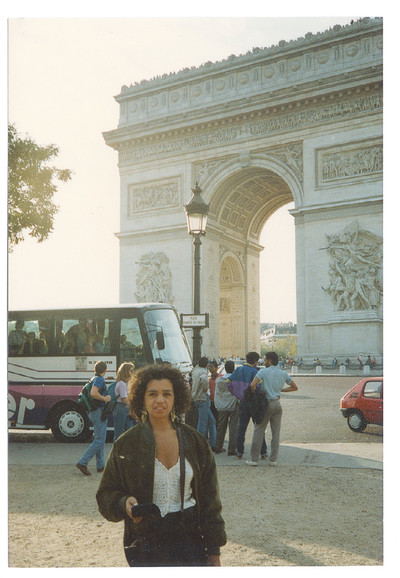

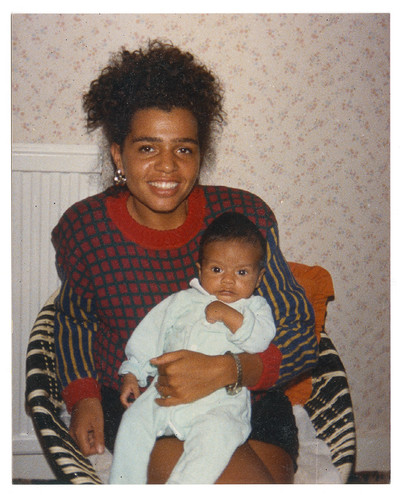

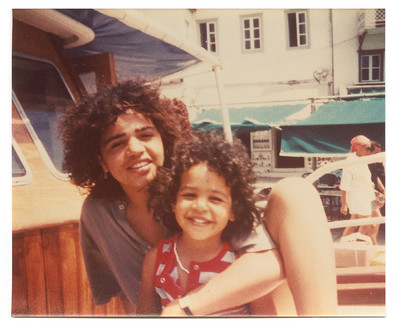

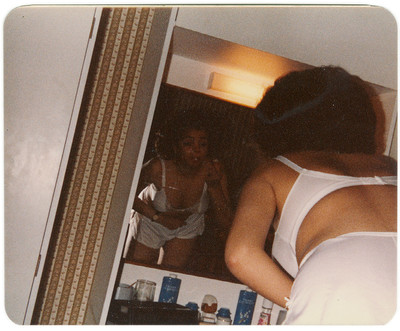

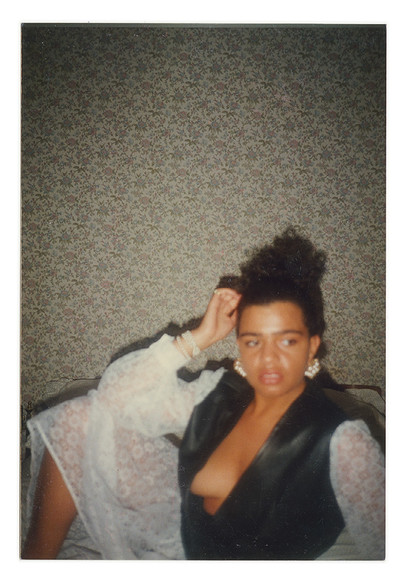

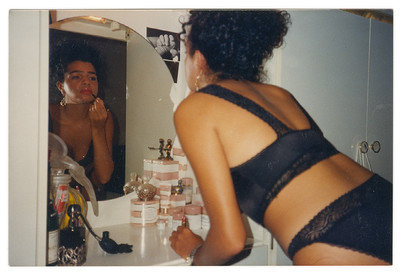

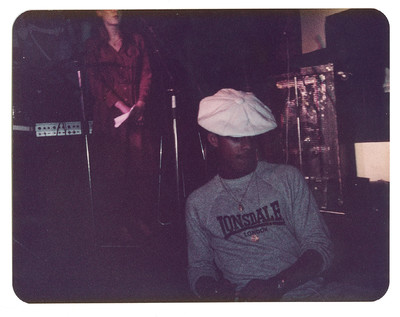

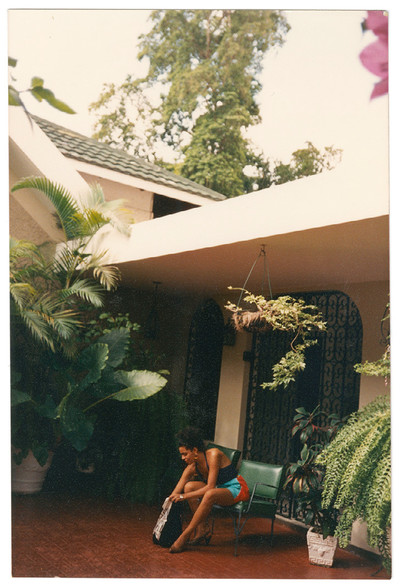

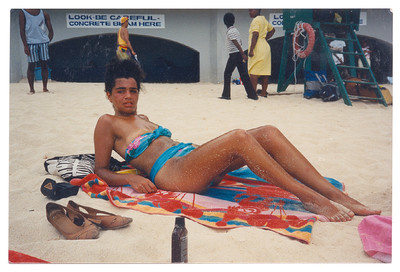

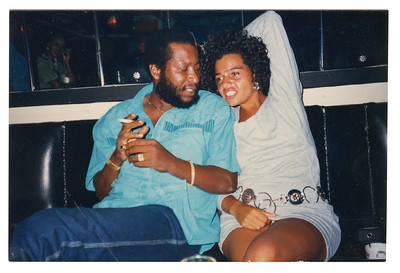

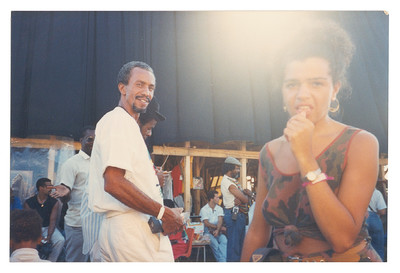

Fundamental to Martine Rose’s approach to her work is a seemingly simple question: why do people wear what they wear? It is an obsession she traces back to her childhood, when she would observe – and occasionally photograph – her big sister, Michelle, and their cousins getting ready to go out, scrutinizing and processing the real-life codes and customs that underlie notions of style. Long before she studied fashion, Martine’s ‘education’ had come on London dancefloors in the 1990s, where clothing was often used to disclose an affiliation to a particular musical genre – a sophisticated visual language built on the heritage of working-class subcultures that had emerged on the streets of the city over the previous half-century.

It was on a foundation course at Camberwell School of Art that Martine Rose first met fellow student and London-born clothing obsessive Tamara Rothstein, but it was only in the early 2000s that the pair bonded while interning as stylists on men’s magazines in Soho: Martine on the monthly Arena and Tamara on its biannual sister title, Arena Homme+ (where, it should be noted, I worked at the same time). Soon afterwards the duo launched a T-shirt label, LMNOP, but after struggling to keep up with orders, they closed it after four busy seasons. Tamara moved on to forge her career as a stylist, while Martine founded her namesake label in 2007, marking the start of an exploration into menswear and masculine style codes.

Over the 15 years since the label’s launch, progressive currents in men’s fashion have tended to push towards abstraction – from flights of fantasy veering towards fancy dress at one extreme to a fetishization of functionalism that risks vapidity at the other. Martine’s response to this has been to ground menswear in the particular and the real, before leading it somewhere new. Reunited and closely aided by Tamara, who has styled the collections since 2016, Martine has taken an approach rooted in her own lived experience and the clothing choices of people she sees in everyday life, rather than arbitrary fashion references. She dedicated her Autumn/Winter 2017 collection, for example, to ‘bankers, office workers and bus drivers’. The City boys who wear their shirts a size too small to show off their gym work; wide boys in square-toed loafers; and even the relaxed style of dad-dancing middle-aged men: all have played a role in inspiring clothes that are wearably familiar, yet executed in unexpected and off-kilter ways. From football shirts cut in extreme proportions, to running shorts trimmed in French-maid lace, to tailored suits made from delicate fabrics meant for women’s lingerie, Martine Rose’s work balances the uniformity of men’s dress codes with the eccentric individualism for which London club culture was once famous, synthesizing conformity with idiosyncrasy, the ordinary with the oddball.

The designer’s insistence on focusing on the world she knows extends to how and where she presents her collections, often choosing show locations with a biographical connection: the Kentish Town primary school her daughter attends; the Chalk Farm cul-de-sac that’s home to Tamara’s sister; and for the Spring/Summer 2023 show, a railway arch in Vauxhall. This south London space had a significance both personal – it was in a club here that the designer celebrated her 14th birthday – and cultural – after the show she spoke about the area’s historical importance to the city’s gay scene. Some of these touchpoints are so personal or niche that Martine and Tamara are often surprised at how powerfully they resonate with a broader, global audience.

This grounding in a recognizable reality gives the label the kind of authenticity that luxury brands have historically struggled to create. It’s the magic ingredient that Demna wanted when he called on Martine to help him design the first three Balenciaga menswear collections. More recently, it is what drew Louis Vuitton’s CEO Michael Burke to her Spring/Summer 2023 show as (at the time of writing) the luxury behemoth looks to find a successor for Virgil Abloh as head of menswear. In October, I met up with Martine and Tamara at the label’s Crouch Hill studio to talk about their subcultural influences, the peculiarities of their approach to menswear, and the growing family of design-team members and model muses they have gathered around themselves. But before we started the interview, Martine was keen to show me through some old photographs – the ones that accompany these pages – that had been gathering dust in her sister’s attic.

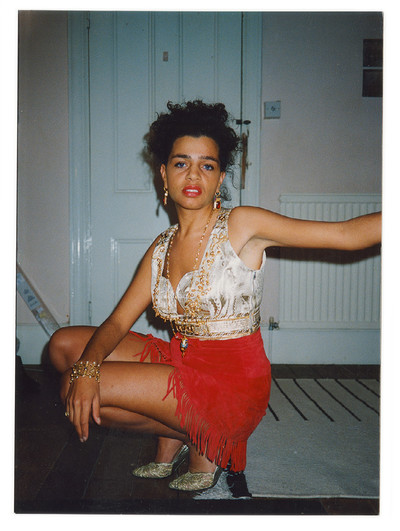

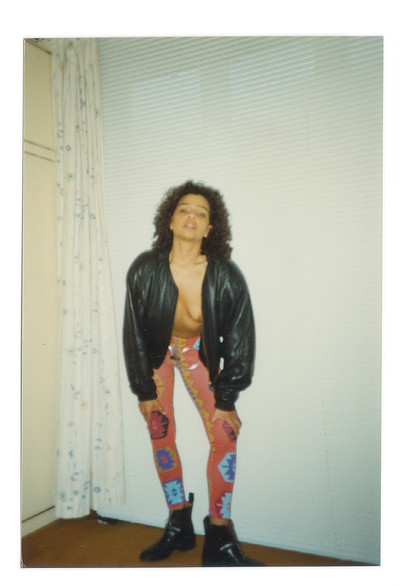

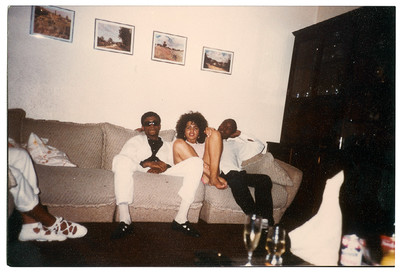

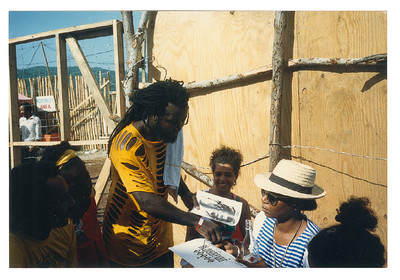

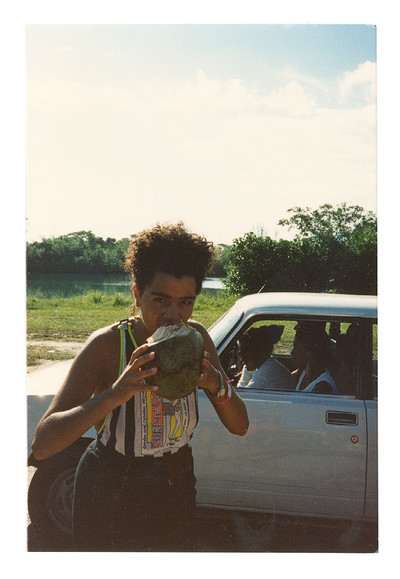

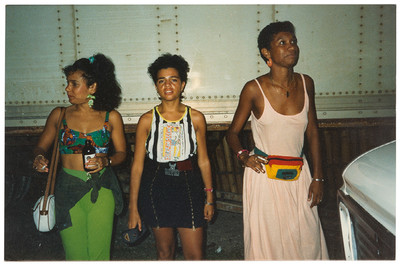

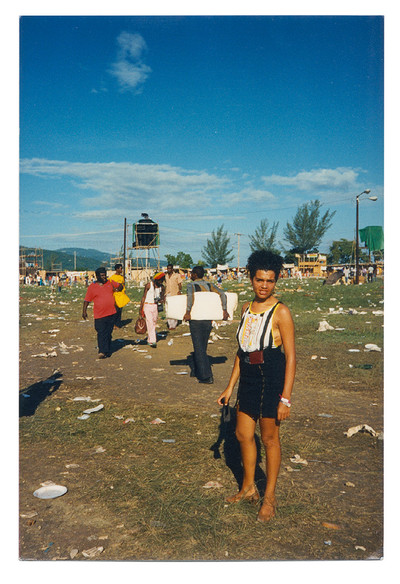

Murray Healy: So these are photos of your sister Michelle, and her friends.

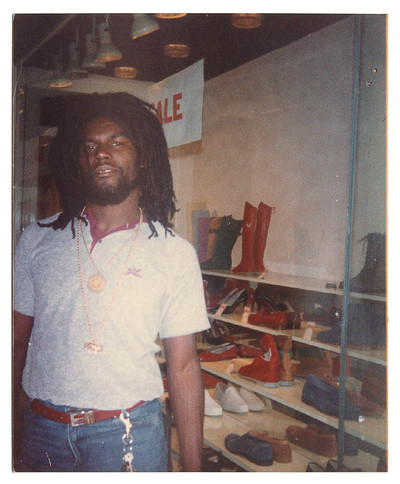

Martine Rose: Part of this story for System is about my influences and my inspirations, and one of my main inspirations was my sister. There’s this big age gap between us – when she was 22, I was 7. That’s my daughter’s age now, and I see how she watches absolutely everything, and I remember watching my sister in the same way. I’ve got loads of older cousins, a really big extended family. We’d all go to my nan’s house, and I used to watch them like a hawk getting ready to go out. My sister really pushed the envelope with fashion. It wasn’t even fashion; it was clothes. Fashion did not come onto my radar. ‘Fashion’ – in inverted commas – was white, rich, abstract – something very removed for me.

Tamara Rothstein: Catwalk.

Martine: Yeah, catwalk. There were a few exceptions to that, crossovers into the street culture that translated into what my cousins and my sister would wear. My sister had loads of Gaultier and was also really into Pam Hogg. The boys would be in Versace jeans, and Moschino was a crossover as well. But by the time it had crossed over, it became clothes, connected to a subculture, usually in music. My sister was really risky and made her own clothes.

Tamara: She was going out a lot as well.

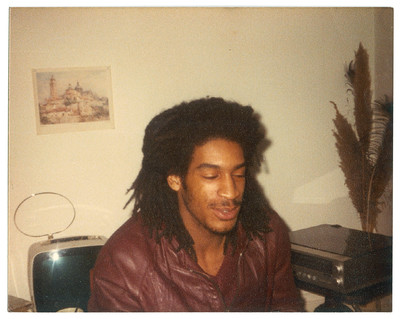

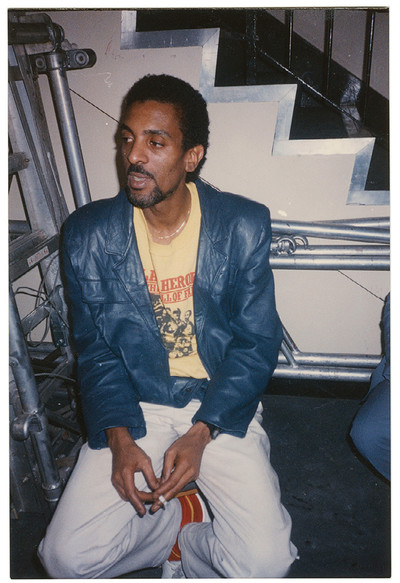

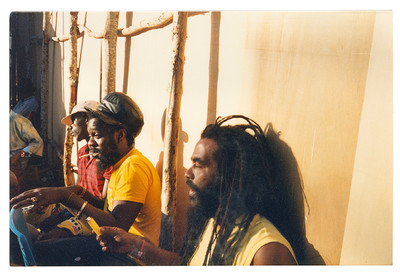

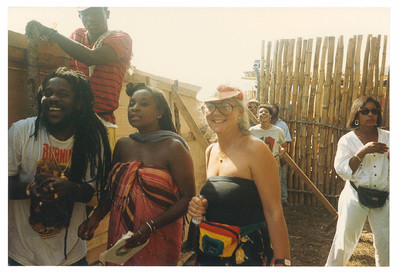

Martine: She went out a lot, and she was into different music scenes. She was into Twelve Tribes, which was like a real dub roots reggae scene, so she was hanging out with lots of the reggae artists coming to the UK and would take me to their recording studios. There was a very UK Lovers Rock scene; she was very into that. I just watched her. I was pretty obsessed with my sister, just watching her be sort of fab in London in the 1980s and 1990s. My cousin Darren, who was a bit younger than my sister, was really into rave culture, going to Camden Palace, Raindance, Telepathy. So I had this broad sense of clothing being associated with different nights and different scenes. I had a really precocious experience of dance culture and music culture and how they affected the clothes. Like I said, it wasn’t fashion. My family’s Jamaican, and there was a very, very particular respect for style. Fashion was something… almost basic; if you had style, that was something else. There was an undercurrent of that. My grandad was a tailor, my nan was a dressmaker. So fashion felt…

Tamara: It’s true, isn’t it? There was a difference between style and fashion then.

Martine: You didn’t necessarily have the money to do fashion. So it was little nuances of detail, like a handkerchief or the way you tilt your hat – tiny little things.

‘My family’s Jamaican, and there was a particular respect for style. Fashion was something almost basic; but if you had style, that was something else.’

Having a family where people made clothes must have demystified clothing, too.

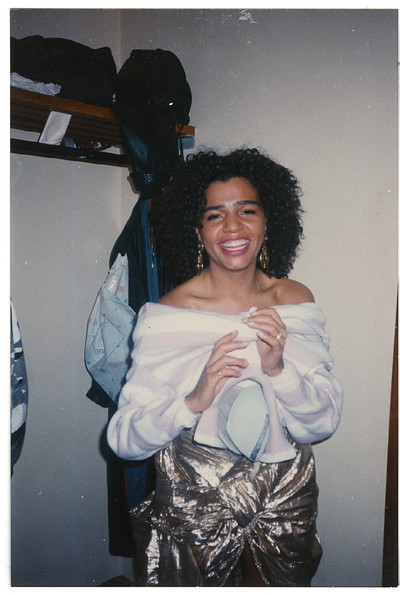

Martine: Absolutely. The family had a dressmaker in Wimbledon called Phyllis. Ah, bless Phyllis. Often my sister or my cousins would go to Phyllis with a tear-out from Vogue or something like that – ‘I want something like this’, take their own fabrics, and Phyllis would just make it. She did it all freehand, on the body. She was amazing. Of course, you weren’t going to go to Versace and buy it, but you could go to Phyllis in Wimbledon, and she could knock it up and make it look fabulous. That gold top that my sister’s wearing in that picture [opposite page], Phyllis made that.

Vogue would have been a reference then?

Martine: Next to her bed, my sister used to have all these Vogues stacked as shelves. She must have had 300, 400. Vogue was a reference, but maybe as something to translate. Less as something aspirational, less looking up.

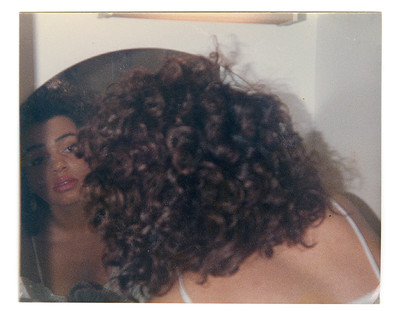

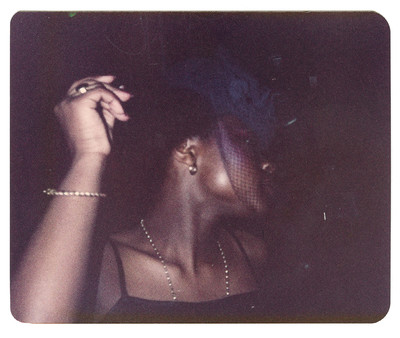

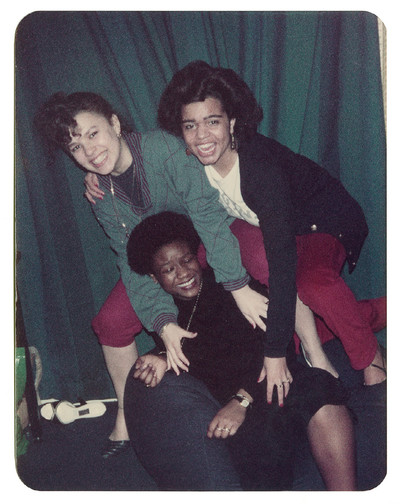

It’s interesting the role that the landline phone plays in these photos.

Martine: I must have been eight or nine when I took those pictures of my sister modelling on the phone. It’s that very classic posing. It’s like Malick Sidibé, the Malian photographer – that very classic studio shot of people on telephones. For my dad’s generation who first moved here from the West Indies, a telephone was a sign that you’d made it, of luxury or success. There’s so many pictures of my sister posing with the phone. With one of those cords. It’s really interesting.

That’s also a recurring motif in Syd Brak’s paintings for Athena posters in the 1980s, which inspired a print in your Spring/Summer 2022 collection.

Martine: Yes! I’ve got it in the studio, actually. It’s so true. I didn’t think about it in that way – it’s very Athena. And there’s loads of pictures of my sister looking in the mirror doing her make-up, with someone over her shoulder so you can’t see the photographer. It’s this way of getting an image of yourself. I guess it’s an early form of selfie.

So did your sister ask you to take these photos?

Martine: Yeah, and I’m terrible at taking photos! Even if the photos I took of her are actually really good.

Tamara: I feel like she would have been directing you because you were so young.

Martine: I was so young. Pictures of her in her underwear, on the phone – very stylized.

Tamara: Like creating a character.

So it wasn’t about ‘I’m about to go out and I want a photo of my look’?

Martine: No! It wasn’t just ‘I’m going out tonight, don’t I look fab?’; it was much more ‘it’s Sunday afternoon, I’m on the phone, let’s do a little photo shoot’.

That must have had an effect on you in terms of how you put a look together and what it means.

Martine: Hugely. I really remember sitting on my sister’s bed and just dissecting it all. We’re really different people – I’m tomboyish, and she was very feminine, very girlie. Her clothes were really sexy. So she did influence me, but not in terms of her personal style at all. There was a playfulness, I think, with clothes, and a pleasure in clothes, in making clothes. That was more the influence.

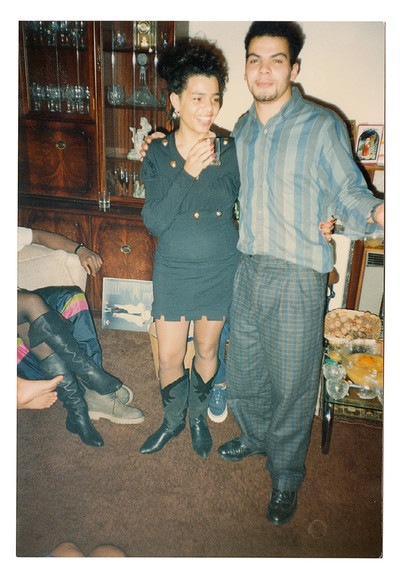

Tamara: And the excitement of going out.

Martine: Totally. I just wanted access to this other world that everyone around me could access. And clothing was a part of it. It was a way in. I was about 13 when I started playing with clothes myself. That’s when I started going out to clubs in London. And then I played with clothes for a different reason: I needed to look older. So, around 13. [Rolls her eyes, quietly says] Fucking hell.

I was reading about you going to Strawberry Sundae when you were 14.

Martine: I had my 14th birthday in Strawberry Sundae, yeah.

Tamara: I had my 15th in Emporium, which is now Sadie Coles’ gallery, in Kingly Street.

Do you think kids are clubbing at that age now?

Martine: You can’t go out at 13!

Tamara: You can’t go out like we could. We talk about this quite a lot – there aren’t that many clubs in central London any more. Nightlife in central London is done and dusted, isn’t it? You used to be able to go down Regent Street and there were a couple of clubs, and then to Hanover Square, dodge into Kingly Street. Then over to the Hippodrome, Leicester Square.

There was an all-night culture around Soho – not just clubs, but bars and cafés too.

Martine: I remember going to cafés on Greek Street after going to clubs. I just couldn’t wait to get into that nocturnal world, and clothes were a part of it.

‘There weren’t many people in popular culture who felt relevant to me. I guess you had Neneh Cherry, Sade. Beyond that, it was people closer to home.’

That culture wasn’t heavily documented at the time. You might see fragments of it in magazines.

Martine: Yeah, fragments. It was tantalizing. I’d see them before they went out, I’d see them the next morning. You’d catch it in the ether, but it was like smoke – there was no proof of it. ‘Where is this thing? Where are you all going?’ It was like parallel universes running side by side, and clothes represented some sort of key.

At that age were there any figures in popular culture you were looking to for inspiration?

Martine: You know, I never really had that. I was really preoccupied with the people who were in my family, I guess. There weren’t that many people in popular culture who felt relevant to me. I guess you had Neneh Cherry, Sade. You look for people who look like you, who you can recognize. Beyond that, it was very much people who were in my immediate reach. I wasn’t looking at models or anything like that.

Were you looking at magazines?

Martine: I started looking at The Face and i-D when I was 14. I was also looking at music magazines. I was really into Mixmag because I wanted to read about the nights out. So it was this cross-pollination thing. It was all of it. It was pop culture.

Tamara: I remember reading Time Out.

Time Out was good for club listings.

Martine: It was really good. I found an old club listing the other day. I was trying to find the address for Strawberry Sundae, because I did my last show in the railway arch [in Vauxhall], and I was trying to work out if it was the same arch that they did Strawberry Sundae in. This old listing came up, and it was amazing: every single night of the week there were so many nights you could go to. Like on Thursday, Gilles Peterson at Bar Rumba, Saturday nights at Subterania or Hanover Grand. And I had that feeling of ‘Oh my God, look at what we’ve lost’.

Tamara: I remember being on the train to sixth-form college looking at all the listings in Time Out, working out where I was going to go. Then I remember coming across sample sales. Remember those? That was also my little way into fashion. I was going to sample sales from quite a young age, just to get something for a good price and get a look at that world. I remember travelling all over for sample sales.

‘Tam and I have worked together for so long, and our relationship, that dynamic, comes from our shared experience of growing up in London.’

You were fitting in nights out between school?

Tamara: Yeah, and doing a lot of lying!

Martine: It fills me with absolute horror. Tam and I have worked together for so long, and our relationship, that dynamic, a certain amount of it comes from our shared experience of growing up in London. There’s this understanding of club culture and stuff like that, but I also think it’s as much about our differences as our commonalities, because we’re very different people. So there’s this tension between us, I think. I have this realness, so my references are always about accessibility.

Tamara: Your clothing always has to be believable – would you wear that?

Martine: It has to be real. Like, it’s not total fantasy. I have to be able recognize it so I can push it somewhere else. What you bring, Tam, and why we’ve worked together for so long, is this arty, this art thing to it.

Tamara: Yeah, this difficulty.

Martine: Another touchpoint for me and Tam is we’re both prepared to really go weird. We’ll never rein each other in on the weirdness.

Tamara: No, and when it works and it’s weird, that’s when we know it’s right. There’s no real reason for it being right, apart from we both know it is.

Martine: We’re both very instinctive – another touchpoint.

Tamara: Again in very different ways. My growing up was very different. My dad had a lot of different girlfriends, very good-looking women who I was always looking at and quite impressed by, watching them wearing clothes and putting it together. And my mum, too. So, it wasn’t my sister; it was really my parents. Although Martine and I are very, very different, we both have this shared experience of looking at older people dressing up. It’s something we still do.

Martine: Observing.

Tamara: I know that we can be in a room, and I’ll see something out of the corner of my eye, and 10 minutes later, I’ll be like, ‘Did you see that?’ and Martine will be like, ‘I really saw it.’ I don’t even have to say it there and then because I know you will have seen it.

‘Although Martine and I are very, very different, we both have this shared experience of looking at older people dressing up. It’s something we still do.’

Why do you think you both tune into the same details?

Tamara: It’s just this real interest in people, and in clothing, and in what clothing says about someone’s personality – where they’ve come from, where they’re going. Also, I think neither of us have ever been stagnant in our approaches.

Martine: It’s very easy to find a formula that works and trot that out for a little bit. That totally makes sense and that’s what most people do. You find that magic thing and you keep doing it. Tam and I have never really done that, and if I fall into particular patterns of design, which is normal, or if Tam does…

Tamara: …with the styling, or putting something together…

Martine: …we can tell each other. I love watching Tam’s process; I find it really exciting. I like giving Tam a whole load of clothes or I like Tam coming in and seeing what she’s drawn to.

At what stage do you come in, Tamara?

Martine: We’re not very rigid with that either.

Tamara: No.

Martine: We’re trying to get a little bit more organized with it, just because the collection’s getting bigger, but you’ve started to come in at fittings early enough to be like, ‘I’m not going to style with that, I’m not going to use that.’ Early enough to make changes, but not so early that it’s still hard for anyone other than the design team to understand. We don’t have a very rigid process. It’s a lot of conversation. There’s a lot of playfulness in our process. And it can feel, I guess…

Tamara: Not very organized.

Martine: Very un-organized.

‘There’s a looseness that small brands have. It’s harder to keep that sensitivity when you’re boshing out thousands of one product. It’s a delicate balance.’

Is there a tension between the looseness of your instinctive approach and your team getting bigger?

Tamara: Sometimes people want organization. We have to be almost like, well, sometimes it’s the organization that can kill something.

Martine: We have to safeguard it, absolutely. I’ve always said, it doesn’t matter how big my brand gets, I always want to feel like a small brand. There’s a certain looseness and a lightness that small brands have. It’s much harder to keep that sensitivity when you are boshing out thousands of one product or whatever, or you’ve got 50 people in your company. It’s a delicate balance.

Tamara: Also, what’s interesting about the process is I can tell what Martine likes and where we’re going, but sometimes she will throw in a curveball and I’ll be like, ‘Fuck – I’ve known you for so long and so intimately, and I still did not see that coming.’

‘Martine will sometimes throw in a curveball and I’ll be like, ‘Fuck – I’ve known you for so long and so intimately, and I still did not see that coming.’’

What you said earlier about not sticking to a formula, what is that keeps you finding new ways of working? Is there something you’re still looking for?

Martine: That’s a really good question! Possibly. Or it’s like a restlessness, but it’s also trust. I really trust Tam. I feel there’s a comfort, a safety net in continuing to explore different methods. You can be who you really want to be in this safe space because you can trust that it’s going to work.

Tamara: It doesn’t matter if you slip up along the way.

Martine: It really doesn’t.

Tamara: I can sometimes put together something disgusting – couldn’t give a shit! You know what I mean? Because we both know…

Martine: …know there’s a safety net.

You need the freedom to do work without holding yourself back.

Tamara: Or being worried about what that person’s going to think of you.

Martine: Exactly.

So there isn’t any self-consciousness?

Martine: No, there isn’t. Definitely not with Tam. I can be self-conscious in lots of other contexts, even with the design team. You know, it’s exposing, being a designer. I know my team feels exposed when they show me some of their ideas, because it is exposing.

You’re explicitly inviting judgement, aren’t you?

Martine: Totally. You’re putting yourself out there.

Tamara: We’re both really ambitious, but not an ambition that wants to own the world.

Martine: We just want to create really good work.

Tamara: I don’t even look at it as fashion. I look at it as a proposition, of what something could be and where it’s going forward and also where it’s been. Because we can be nostalgic. [To Martine] I told Murray that we referenced him walking to the gym in Soho.

Martine: That’s true. That was in the last collection. ‘Go on, put your gym bag over your back and walk up and down. Let’s pretend it’s Compton Street in 2008.’

Again, it comes back to the culture of a very specific time and place and you both having experienced that.

Martine: Absolutely. It has to be rooted in something I recognize. It can go somewhere else, but I have to be able to connect it to something I can recognize. Sometimes I’m surprised when it resonates with so many people. Like, I had this amazing response from people who came up to me in New York. That is so surprising, because they’re such specific references…

That you think there might only be 50 people in the whole world who’d get it.

Martine: Exactly, yet somehow it manages to transcend that. I also really enjoy how it becomes this other message to someone else or that people actually do understand the reference, when I thought it was much more niche. People do get it or a version of it.

Tamara: Also, we never pull from just one thing, do we? It’s all these little bits coming together.

Martine: Layers and layers of references, and sometimes I don’t even want people to get the reference.

Tamara: Sometimes we don’t even know where it’s come from.

Martine: It’s just there [indicates the ether] – like smoke somewhere.

Tamara: There was a guy who we used to see around Camden, do you remember? We saw him one day in three different places. So sometimes it can be from a stranger. It is everyday people in everyday jobs.

Martine: Complete strangers you can project all sorts of stories onto.

Tamara: I project quite a lot of stories.

That’s a very specific way of approaching style. Not fashion as dressing up, but about why people wear what they wear.

Martine: It’s codes. Yeah, exactly – there’s an elegance, a style. People have different definitions of what makes someone stylish, and I’m obsessed with these notions of style.

That distinction between fashion and style, which used to be so specific, does that still exist?

Martine: Unfortunately not, I don’t think it does. The Blitz was on TV the other night, did you watch it? It was fantastic, obviously, because it was fundamentally that. You couldn’t go out wearing the same thing twice, and you had to make it. It wasn’t about buying; there was nothing off the peg. It was about individuality in the most extreme way – style.

Tamara: There used to be style magazines and fashion magazines, but I wouldn’t know what the difference is now. It’s also a sin of designers, where brands want a full look. That can basically make every magazine look a bit like a shopping guide. What is a style magazine when you can’t style?

Martine: You’re just not creating a proposition.

You mentioned your team growing. Is there any pressure for your brand to keep growing from the outside?

Martine: There’s definitely pressure to keep growing. There’s a pressure on myself to keep growing as well, but…

Tamara: It’s to do better.

Martine: It’s wanting to do better.

I mean in terms of business, expanding – like doing eight collections a year.

Martine: There is, of course. There are definitely pressures to grow. But I also partnered with Tomorrow, and they are really sensitive to me as a designer. I was already 14 years in when they joined me, so I already had a fully formed business. I was very much like, ‘I need to feel like I have a sense of control over this thing.’ If I’m not ready to do four collections a year, I’m not going to do it. That’s fine. I’m in it for the long run. I really enjoy what I do; I like working with the people I work with; I like working with new people. I’m in no rush. I’m happy to grow, but it has to be thoughtful, it has to be done at the right time – it’s not growth at any cost. A friend on the design team actually said to me the other day, ‘I think you can only do what you do because you don’t think about tomorrow.’ And it’s true – I really don’t think about tomorrow. That’s a curse as well as a blessing. I do not plan; I really trust in my ‘now’. I’m willing to sacrifice the security of having a plan to just enjoy what I’m doing now and who I’m with and what I’m on. I’m not a worrier. Not at all, really.

Tamara: We’re really lucky because Martine has – maybe through only being in the moment – carved out a pretty brilliant scenario for us all. We went to art college together, but we weren’t friends then. We also had a mutual friend, Meera, who has always been Martine’s print designer and works across everything now, and another friend, Chau [Har Lee], designs the shoes.

Martine: Who also went to art school with us.

Tamara: So the four of us met at this very important moment in like 1998 at Camberwell.

Martine: When we were 18. We didn’t find our people until art school.

Tamara: Then we were like, ‘These are my people. They understand us.’

Martine: Yeah – ‘Thank fuck, these are my people.’

So you met at Camberwell College of Arts on the foundation course?

Martine: Exactly. Then we went off to do our degrees and lost contact. Not really lost contact…

Tamara: I’d still hear about you, because of Meera.

Martine: Then we interned at Arena. We found each other again through work and started working almost straight away when we set up LMNOP together.

Tamara: That was Meera’s brainwave. She was like, ‘I think you two should do something else. Why don’t you two come together and do this?’ She kind of match-made that situation.

Martine: I didn’t know that. Did she?

Tamara: Yeah, she was like, ‘You two should have a conversation about this.’

Martine: That’s funny. That was such a funny little art project we were doing and then it just worked. That was bizarre.

Tamara: Do you remember us printing on the Arena Homme+ copier, Murray?

Martine: We’d go back into the office and use the photocopier at two, three in the morning.

Tamara: We’d use everything. Everything. I think you had to.

Was this a substantial order?

Martine: It was 200 T-shirts or something. By hand. We didn’t know what we were doing; we had no sense of time or making money or anything. So we just worked all the time, and then worked in bars in between.

Tamara: It’s a common story.

Was that a form of protection, that naivety where you go into it not knowing how difficult it can be?

Martine: Oh fucking hell, yes – otherwise I wouldn’t have done it. When I finished LMNOP, by that stage, Tam knew for sure she wanted to be a stylist and I knew for sure I wanted to be a designer. So it was a real testing ground.

Tamara: LMNOP did grow a bit, but because what we were making took us so long we weren’t earning anything from it.

Martine: We were losing money hand over fist, but we didn’t do it for long enough to really get burned. We did it until we got bored. It didn’t burn me enough not to start my own business…

Because you jumped straight back in with your own brand.

Martine: I jumped straight back in. But I honestly think, if I knew then what I know now, I wouldn’t do it. No, I fucking wouldn’t do it. The only reason I’m here is because the naivety protected me at the beginning. For sure.

That ties into what you were saying about designing for the moment and not looking ahead.

Martine: That’s true. Absolutely true. I don’t have a grand plan.

Tamara: I also think you just really enjoy making clothes.

Martine: I do.

Tamara: You really enjoy it. It wouldn’t even have mattered if you didn’t get an order, you’d have just carried on. It was an art form.

Martine: It was. [Sighs] I don’t know. It was fucking hard. If Balenciaga hadn’t called, if Demna hadn’t called at that time, I think I would have absolutely chucked it in.

Really?

Martine: I was squatting, my daughter Valentine was born [in 2015] – I had to grow up really quickly. I was still working in a bar until I was 34, I was doing bits of teaching. I loved working in clubs, I loved working in bars – loved it. I loved that interaction because I really love people. I find people so inspiring, and I met some mind-blowing people working in bars. I would happily have carried on working in bars, to be honest. I’ve also always been a bit ambivalent about the industry. Then when I had Valentine and I got kicked out, I was just like… I don’t think I can do this any more.

Tamara: It’s that responsibility, isn’t it?

‘I was squatting, my daughter Valentine was born in 2015 – and I had to grow up really quickly. I was still working in a bar until I was 34.’

When you’ve got other people depending on you, it’s a different story. It’s interesting that you loved working in clubs and bars, because your understanding of clothing comes through that specific living, breathing social context – it’s not some rarefied discourse.

Martine: Exactly. It’s part of the same thing. I worked in Blacks and Century in Soho, and Plastic People… All of that knowledge, all of those people who I met – I can’t even tell you how they’ve informed my design work. These characters I recall, and these moments and nights, they somehow get mixed up in my head and vomited out for the collection somehow. [Laughs] They really do, and I still find myself referencing people and nights. I miss working in bars, actually. It was much more than just part-time work to me.

It was almost research?

Martine: Exactly.

What do you do now to get that access to watching people in that way?

Tamara: Casting.

Martine: Yes, that’s true. We do quite a lot of street-casting, so we meet some wonderful people. You’re so right, Tam.

Tamara: And we really love wonderful people. Which sounds really cheesy, but we would never put anyone in the show…

Martine: …who we didn’t like.

Tamara: Even if they were brilliant.

Martine: Even if they were beautiful and made the clothes look good. There’s a characteristic I think that Tam and I both find appealing – I can’t define it, but there’s some quality that’s really important. There’s definitely a connection that we feel to the casting, where we have to feel the relationship with that person. Obviously we can’t go out and research in the way we used to: going to clubs and bars, chewing the fat – we don’t have the time to do that. So we both get that from casting. I’m still really interested in people; I’m interested in my team, in what they do. I’m nosy, basically! With street-casting, it’s fun to watch someone come to life and be playful with clothes. There’s one guy that we work with in particular, Will – he’s wonderful, he’s a chef. I don’t think he can see it, but he has something in him that is magical.

Tamara: Magical.

Martine: You see him really grow in the clothes when we dress him up. We put him in weird shit and he goes with it. It brings something out in him.

Tamara: People feeling good about themselves is why we’re in this, and clothes do that.

Martine: I think we had that a lot on the last show, didn’t we?

Tamara: Yes, more than normal.

Martine: I don’t know if it was because it was our first show after Covid and people were really happy to get together, but you could just see the casting – they were so pumped. It wasn’t a job to them; it was more than that. Like, being their full selves.

I want to take you back to something you said about the differences between menswear and womenswear. Do you think there’s more creative freedom in menswear at the moment?

Martine: Totally. I feel like there’s a saturation in womenswear. It’s very hard to find your lane because it’s so massive.

Tamara: You have to do everything as well. Like, if women start wearing peplums, you have to do that too to get those sales. That’s why I think women’s is so hard.

Martine: It’s just enormous. How do you find your voice in it? It’s so crowded.

Tamara: It’s a bit like when I used to walk into Topshop when I was younger, when I was in my early twenties, and I’d be like, ‘Oh my God, who am I?’

Martine: Overwhelmed. What tribe?

Tamara: Am I a cowgirl? Am I a hippy? And I think that’s what’s happened to women’s. It’s so easily been destroyed, whereas men’s has somewhat been protected.

Martine: Fundamentally, there are way more rules in menswear – and that’s what I really, really enjoy: that there are still things to push against. There’s not much to push against in women’s. I find the limits in men’s really exciting.

Is the resistance of men to wearing certain things something you feel you have to challenge?

Martine: I enjoy challenging it, but I don’t feel like I have to challenge it. I enjoy it when it’s not a ridiculous proposition; again, it’s not a total fantasy. The example that comes into my head is when we put [model and musician] Miles in a women’s camisole and he still looked so sexy. It’s not something for something’s sake. I want it to be believable. If someone could just think that it’s a possibility for a second, you know what I mean? That it’s a real possibility. [Showing a shot of Miles from Spring/Summer 2021 on her phone.] I mean, it’s so sexy. I think he just looks so beautiful in that.

Tamara: But it’s everything: it’s the clothes, it’s him, it’s the body language.

Which reinforces how vital the casting is.

Martine: Really important. You do fall in love with these people, these characters we meet, over the season a little bit. They are very much part of the process.

Tamara: We really care about them and then it happens that they care about us.

Martine: Then they’re really invested in the collection: ‘We really want to do well.’ Think about the last show – they were really pumping themselves up: ‘It’s going to be great. I’m going to do my best.’

Tamara: I think they enjoy the fact that…

Martine: …they’re participating in it…

Tamara: …and we’re all really going through this intense process together and we’re going to come out of it and love it and have fun.

Models: Thibault Aedy, Darrell Barrett, Shee Fun Chan, Annabelle Moedlinger, Oliver Newman, Oliver Hadlee Pearch, Will Peers, Clifford Rose, Shivaruby.

Hair: Cyndia Harvey.

Make-up: Marina Belfon Rose using Chanel Le Lift Pro and Éclat Lunaire Oversize Illuminating Face Powder.

Nails: Edyta Betka.

Production: Partner Films.

Casting: Isabel Bush.

Photography team: Bella Sporle, Albi Gualtieri, David Mannion, Max Hayter.

Styling assistants: Georgia Illingworth, Alex White.

Hair assistant: Emilie Bromley.

Make-up assistant: Tia Louise Clement.

Movement direction: Darrell Barrett.

Darkroom services: Hammer Lab.

Retoucher: Aly Studio

![1985. [Left] ‘My older brother Richard in nan’s house, [right] and with his friend, Soljie, outside the house.’ - © System Magazine](https://system-magazine.com/media/pages/issues/issue-20/momentum-martine-rose-tamara-rothstein/2b7e5ceb4d-1683648902/system-20-martine-rose-46-400x.jpg)