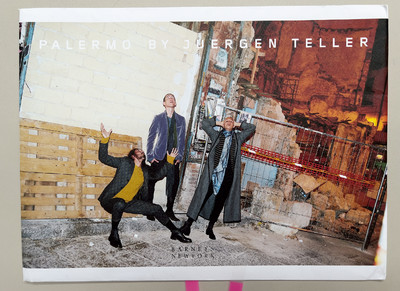

For 11 seasons, Dennis Freedman and Juergen Teller took Barneys’ catalogues out on the road.

Interview by Thomas Lenthal

Photographs and layout by Juergen Teller

For 11 seasons, Dennis Freedman and Juergen Teller took Barneys’ catalogues out on the road.

Back in 1998, W magazine’s creative director Dennis Freedman put a call through to Juergen Teller. Freedman was keen for the London-based German photographer to join his roster of go-to contributors, as he continued to carve out the monthly title’s unique place in the increasingly crowded, cut-throat and (then) commercially robust world of American fashion print media. As Freedman saw it, photography was a profoundly artistic practice, something noble, meaningful, and with the capacity to transcend the longstanding clichés so abundant in the ‘pages from the glossies’. In awe of colour-photography masters such as William Eggleston and Stephen Shore, as well as Robert Frank’s piercing vision of America, Freedman’s modus operandi was clear – put the photography firmly before the fashion. ‘William Eggleston didn’t style his subjects,’ he says today. ‘They wore what they wore and what they wore was just a part of them. The picture wasn’t about that.’

On the third time of trying, Freedman successfully coaxed Teller over to New York to take a meeting at W’s office in the Fairchild Publications HQ on 34th Street. Initially, there was talk of shooting a big-budget fashion story in Egypt, the Seychelles or Jamaica. But Teller, observing with wide-eyed disbelief the corporate surroundings – the vast open-plan office, the individual ‘greige’-coloured cubicles, the slick but soulless furniture, the fax machines battling for space with indoor plants – suggested shooting in the office itself. The resulting 30-page story, ‘Editor at Large’ (February 1999), featured Stephanie Seymour as the ‘editor in chief’, Shalom Harlow as an employee eating take-out lunch in the staff kitchen, and Naomi Campbell in reception on a casting go-see. The pictures were resolutely postmodern – a self-referential observation of the culture and nature of the fashion magazine – and were, crucially, unretouched. The shoot set the tone for a creative partnership at W that stretched over more than a decade, resulting in a boundary-pushing body of work that both examined and redefined the role of fashion editorial for the new millennium.

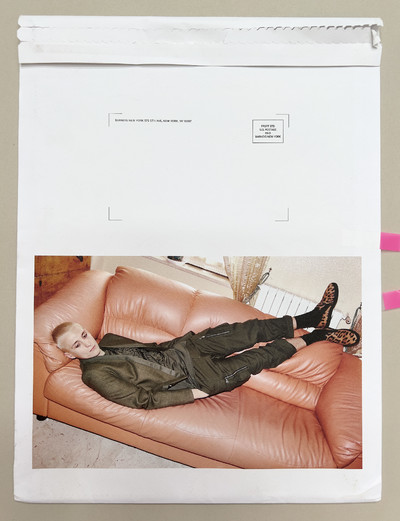

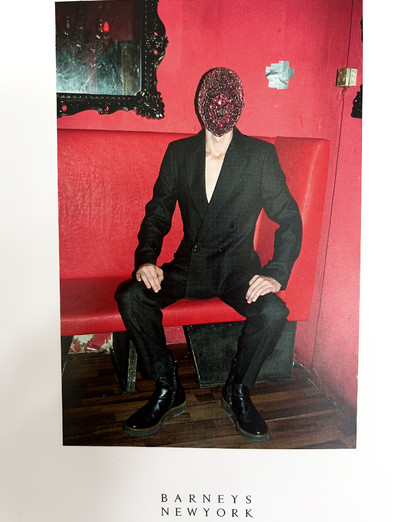

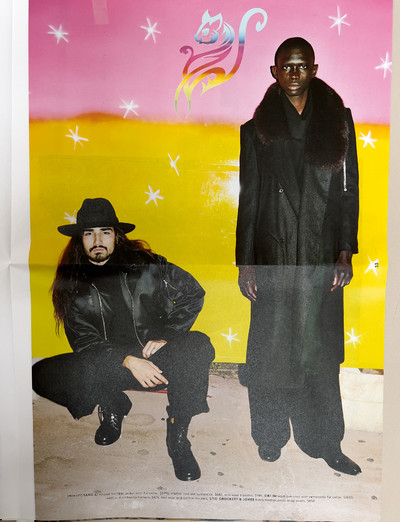

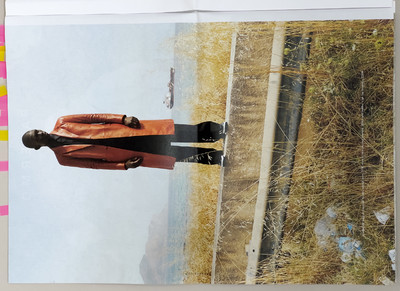

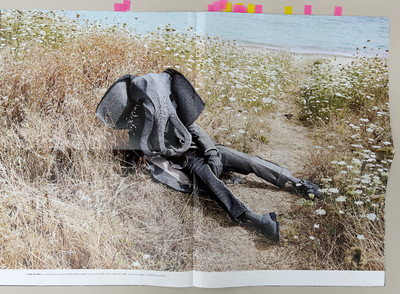

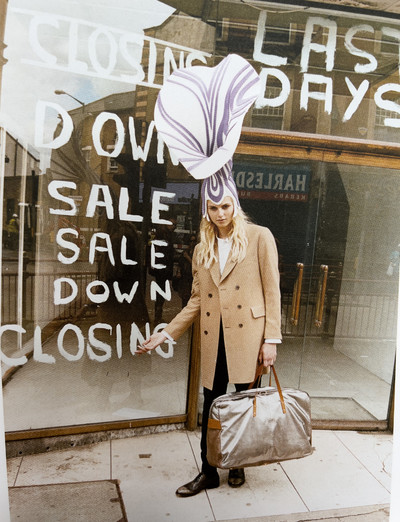

In 2011, Freedman, by then widely recognized as one of fashion’s most committed creative directors, left his role at W to join New York retail institution Barneys. One of his first moves as creative director – a job that included overseeing everything from Barneys’ corporate identity to its flagship store’s window displays overlooking Madison Avenue – was to call on Teller to shoot an ongoing series of print catalogues, initially featuring the store’s seasonal mix of men’s fashion (womenswear was added in the third season). The pair set themselves a creative brief that today seems almost utopian in its simplicity: where shall we go to shoot? The answer was culturally and geographically light years from fashion’s traditional backdrops of Paris, New York and LA, and became emblematic of the duo’s adventurous, unpretentious and idiosyncratic approach. Over the following six years they would shoot in Panama City, Tirana, Frankfurt, Palermo, Tel Aviv, New Orleans, Belgrade, Athens and West London (‘on the wrong side of the Harrow Road,’ says Teller), as well as heading to the Cannes Film Festival and Miami Art Basel without so much as an invite or accreditation to their names. Once on location, the shoots adopted a production ethos loosely defined by Freedman as, ‘Let’s go out and see – and shoot – what we find.’

Assembled and viewed today, the collective work shines a light on a time in recent fashion history – on the cusp of the social-media revolution – that feels as freewheeling as it does sophisticated, innocent, nostalgic even. Today’s all-prevailing digital culture of hashtags, algorithms and the infinite scroll had yet to sideswipe and reformulate so much of fashion photography. Even rampant celebrity culture is given relatively short shrift. The only hint is a low-key, seemingly random appearance of Almodóvar regular Rossy de Palma, poking her head out of a length of industrial concrete piping on a Miami construction site, a Balenciaga combat boot perched on her head. (The reason for her appearance? ‘We just bumped into her in the hotel lobby,’ says Teller.)

Produced between 2011 and 2016, the Barneys seasonal catalogues were subject to limited distribution – principally to loyal US-based customers and the brands featured within its pages – and precious little advertising placement (‘maybe once or twice in Artforum,’ recalls Freedman) or digital hype. This seemingly under-the-radar presence has since made them some of the most coveted fashion ephemera of recent times, while also coming to symbolize the end of an era in American fashion.

What happened next has been assigned to the annals of modern fashion history (or rather, tragedy). Freedman was let go from his role in 2017, following the departure of Mark Lee, the CEO who had hired him. Within three years, Barneys had fallen into bankruptcy and closed its doors forever.

Keen to explore this seminal yet often overlooked body of work, System spoke to Dennis Freedman and Juergen Teller about the liberating nature of having to shoot head-to-toe grey suits, and why their Barneys catalogues continue to represent an antidote to the endless flow of ‘painstakingly boring and overproduced’ commercial fashion imagery.

Thomas Lenthal: Prior to shooting for Barneys, the two of you had established a longstanding working relationship that had yielded some exceptional editorial stories for W magazine. Did the pair of you have any discussions about how the commercial environment of shooting for Barneys might impact this?

Dennis Freedman: I’ve never really considered there to be any significant difference between editorial, or for the lack of a better word, commercial work – I see it all as photography. Of course, there’s always been the sense that advertising is much more conservative and product driven in a way that, for me, generally lacks any real creative ambition. In this instance, it didn’t make any difference. The real challenge was: what can Juergen and I do after working together for 10 years in what’s been a kind of series? Because the stories we’d done at W were basically all rolled out one after the other.

Juergen, what was your perception of Barneys prior to Dennis calling you about shooting the catalogues?

Juergen Teller: I had heard of Barneys, of course, and I’m sure I had stepped inside Barneys before I worked with Dennis on this, so I knew that it was a pretty progressive and interesting department store. We had such a strong friendship and working relationship – as Dennis says, over 10, 12 years with W – and it was something I was looking forward to exploring in other areas, so when Dennis mentioned Barneys, I didn’t have to think about it too much.

Dennis, were you given more or less carte blanche to create work that you felt would be successful in expressing what made Barneys unique?

Dennis: I have been unbelievably lucky in my professional life, because my first editor was Patrick McCarthy [at W] who absolutely, 100% trusted me, to the point where he never even knew where I was. I don’t mean that facetiously; I could have been in China and he wouldn’t have known. And then [Barneys CEO] Mark Lee hired me; he certainly knew what he was getting with me. It wasn’t like, ‘OK, can you now be a different creative director?’ Mark understood that this was a legendary brand, and he was committed to creating something extraordinary; he wanted to create his own imprint and we both felt by doing campaigns like this, it would differentiate us from our competition, which was essentially Bergdorf Goodman. It took someone like Mark, a visionary, to achieve this, and certainly to allow me the trust to work.

‘It was crucial that we didn’t go to New York, LA, or Paris. We thought, let’s not go to Berlin, where everyone goes; let’s go to Frankfurt instead.’

What was the starting point for this work? Can you recall the earliest conversation you had about it?

Dennis: After several conversations, Juergen and I came up with the idea of ‘where are we going to shoot?’ We were very careful about where we went. We didn’t just say, ‘OK, here’s a pin on the map’; there was always a reason, and the reason was based on a mutual feeling. Part of the idea was to shoot in locations that were transitional spaces; in other words, if you were going somewhere else, you would do a stopover in Frankfurt. Although we ended up in Albania for a whole different reason [laughs], which probably says a lot about the overall nature of the work we were doing.

Juergen: It was very important that we didn’t go to New York, LA, or Paris. Similarly, we thought, let’s not go to Berlin, where everyone else is going; let’s go to Frankfurt instead. So we picked these more exotic locations and we really dived into the local scenes there. We got to see inside doors that were opened for us; it was really exciting.

Dennis: It’s telling that Juergen uses the word ‘exotic’, because what I find interesting is the extraordinary in the ordinary. I mean, if you go to Frankfurt you’re not necessarily expecting exotic, but the reality is that in that kind of ‘unspectacular’ city, you can find so many strange and wonderful things. We found that in every place we went; it wasn’t like we went somewhere knowing that we’d find spectacular interiors.

Juergen: One of the main things was that we always worked with the same team: Dennis, Emanuele [Mascioni], who did a brilliant job on production and scouting the locations, the same stylist, Poppy Kain, and mostly, the same hairdresser, Syd Hayes. So every six months we all went on what felt like an exciting school trip, a shared adventure.

So there was a framework, but the framework was ‘adventure’.

Dennis: What I’ve always found really satisfying is that Juergen and I are very much inspired by, for want of a better word, mistakes. By things going wrong. By being under pressure and not having all this time. It’s what animates our work.

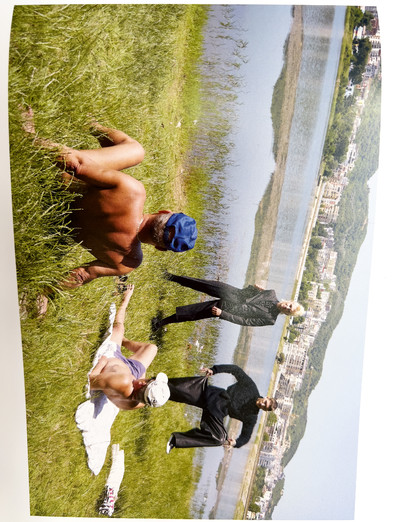

Juergen: Also, when we set certain things up – and this is really important – it was so loose and so neither of us was afraid to miss the point. There was such an openness to trying things and not being afraid. That’s what made it so exciting, because the things we dreamed up turned out to be extraordinary. We just made the most of any situation; we helped catapult each other to make better work.

Dennis: Juergen’s right. We never knew how it was going to turn out, and that’s what made it exciting. Do you remember, Juergen, in Belgrade when we hired a local hairdresser? We didn’t even know who he was, it didn’t matter; all we knew was that he had a hair salon. It was something that I often think about. I mean, how many brands would just be like, ‘OK, we’re going to Belgrade and we’ll get someone local to do the hair’? But that was the success of the project. Because the local hairdresser guy brought something different to the whole dynamic.

‘What I always find satisfying is that Juergen and I are very much inspired by, for want of a better word, mistakes. It’s what animates our work.’

Did you cast people locally as well?

Juergen: No, not really. There is a great casting agency in Düsseldorf called Tomorrow Is Another Day. The main person there [Eva Gödel] has a great eye for different kinds of interesting looking people. Balenciaga now uses them. So we used this agency, and we always did the casting beforehand. It would have been too difficult to manage that on location, on top of everything else, because we had so much to photograph.

Let’s talk about the clothes for a moment. Was there clear direction from Barneys of what needed to be shot?

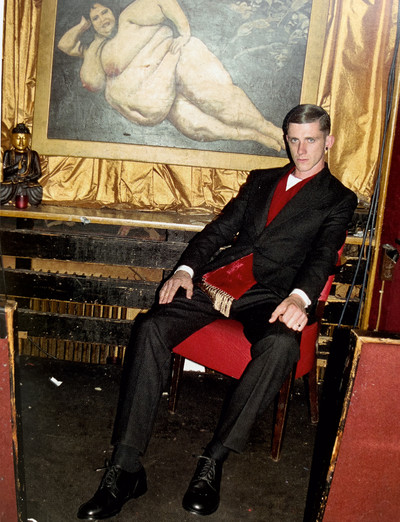

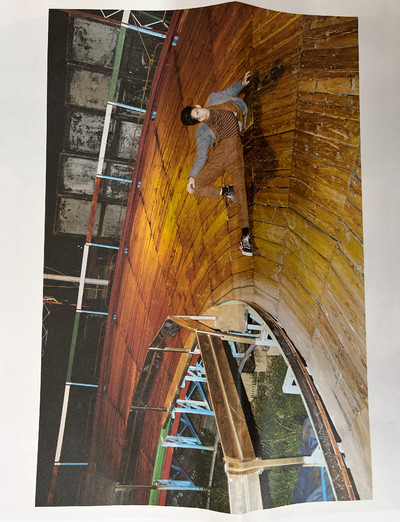

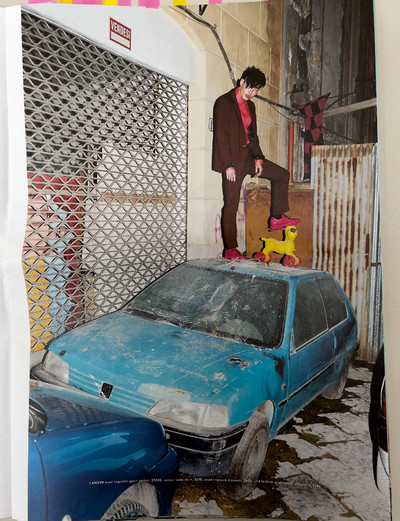

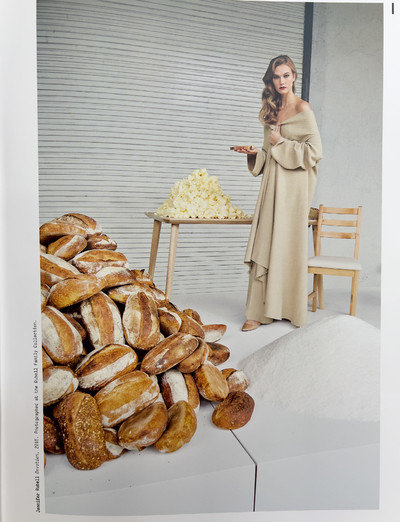

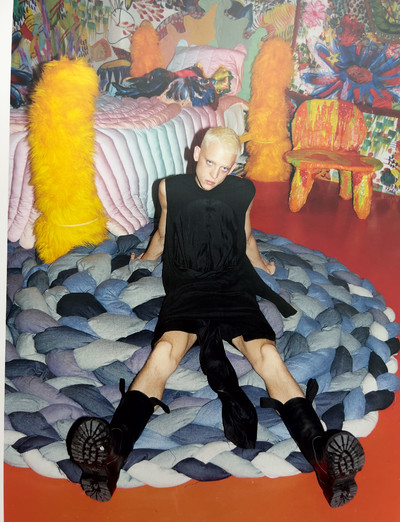

Juergen: For Barneys and for Dennis, it was very important to always have the clothes photographed from head to toe. Even for advertising, I can just do a head shot, or certain crops, and it works really well, but this was each designer’s look from head to toe: Yohji Yamamoto from head to toe; Armani from head to toe… Initially, that created a question mark for me, but also a challenge. We used it to our advantage, because by shooting head to toe you’re able to see more of the location and the surroundings. What I saw at first as a hindrance became one of the best things about these shoots, I think.

Dennis: And it wasn’t just Yohji Yamamoto; it was also brands like Zegna – with clothes that could not have been more conventional. You’d look at the first spread in the catalogue and it’s a grey suit! I’ve thought about this and I see these images as being a bit of a precursor to this maximalist aesthetic; we were shooting conventional clothes in these maximalist ways. So the contrast between the simple grey suit and this kind of bizarre setting in an often rather ordinary location, was really interesting. We were clashing two cultures, and that gave it something more discordant.

Playfulness had long been an integral part of Barneys’ DNA. Was this on your mind when you began the shoots?

Dennis: One thing I can say – and this is why I think I always, always had such a rewarding experience – is that for Juergen, there is a very thin line between this maximalist approach and something kind of obvious or even camp. Juergen can walk that line. Not that we didn’t fall off once in a while, but it was never cheap and was always subtle. That might be a weird word to use, but I believe that…

Juergen: It’s true.

Dennis: I’m not making a value judgement on any photographers who have been influenced by Juergen, however, it is so obvious to me where those differences occur, like the subtleties of where someone is placing their hand. It was hopefully ambiguous, too, and so I never worried about working with Juergen because if you have that, you know when it crosses the line and he would say, ‘No, no, no, that’s not good.’

Today, even with editorial assignments, you can seldom go to a place with so few preconceived ideas or maybe none at all, and say, ‘We’ll take it from here’, and then just really embrace the reality of what is around and be open to anything because you really are not expecting anything.

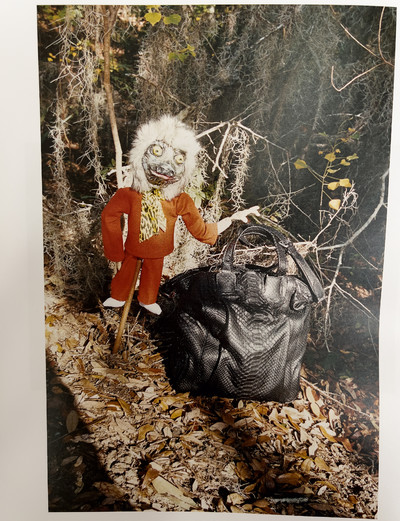

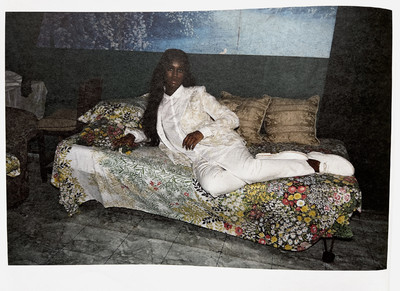

Dennis: That was the idea. New Orleans, for example, was a really interesting choice. It is a city unlike any other in America. It has a prominent community of vampires and witches, and I am not being glib about that; it is real. We had someone extraordinary helping us who really knew the underbelly of that city and I remember ending up at a genuine witch’s house. Then you have the Bayou, which is one of the strangest places in America. New Orleans gave us something that you will never find elsewhere in the United States or anywhere else because of the African-American, Spanish, Creole culture there. And all that came about because we were open to anything.

Juergen: I mean, we went to Panama – I’d never thought I’d go there!

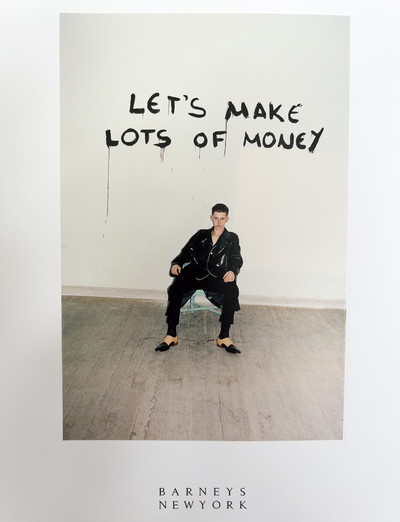

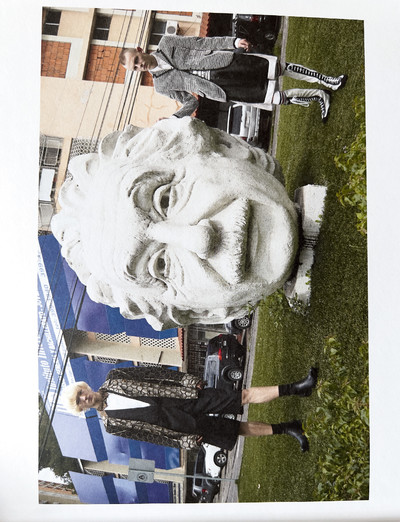

Dennis: There was the canal, which we learned a lot about. This project came with a lot of learning, too; it was about getting outside the golden carriage that many of us exist in within fashion. It is hard to turn away a golden carriage, but sometimes you need to get out. One thing I’d forgotten about until I was looking through your layouts for this story was that, in the middle of Panama there was this huge head of Albert Einstein! All of a sudden, Albert Einstein is popping up out of the grass. I have no idea why it was there. Then that time we were in Athens, and we went to a gallery and one of the wall pieces was called Let’s Get Rich…

Juergen: No, it was Let’s Make Lots of Money…

Dennis: That’s right. Athens was going through its worst economic crisis at the time and we had actually delayed our trip for six months. Just before we had initially planned to go I called Dakis Joannou and asked him if he felt it was appropriate for us to come at this time and take photographs of clothes? And he said, ‘I don’t think you should come right now.’ And then six months later, he said, ‘I think you should come now; I think it’s time and we need this.’ Then, on the wall there were those words ‘let’s make lots of money’ and that picture of the guy in his black suit sitting there. It just said everything. You cannot scout these things; you just can’t. You are going to find them if you know where to look – that is the secret.

How did Albania come up as a location?

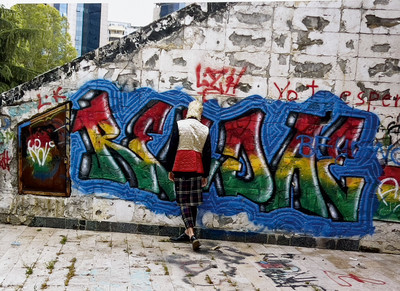

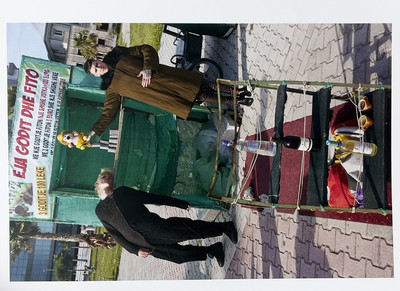

Dennis: Emanuele called Juergen from the airport in Tirana and he said, ‘There is a hotel across the road, an airport hotel, and it is called Hotel Jurgen!’ That was all we had to go on; we didn’t know anything else. Juergen called me and we said, ‘Oh my god, let’s go!’ We knew that there had to be many interesting places. Albania was like North Korea for many years and had been shut off from everywhere. It was just beginning to open up, and I was so excited to get there. We were completely inspired.

Juergen: People in all these places were very open and curious, and never cynical. In general, whenever I shoot in Italy, things are possible; France is more difficult; in America, you need permits for everything; and London is getting increasingly difficult. All these other places welcomed us with open arms.

Dennis: Going to Albania was really special because I am pretty sure this was the first big commercial fashion shoot that had taken place there. For us, it was the idea of seeing a country that was emerging; you could see and feel the beginning of, for the lack of a better word, a democracy, and we were witness to that changeover. Being in the business that we were in is more than just work, it is life, and a privilege to be going around the world. Believe me I know how lucky I am.

To what extent did you have local producers or contacts, or was it more a question of arriving and seeing what to do?

Juergen: We always had contacts and it was always pretty well researched. Of course, we didn’t know exactly what, but we had the guidance of people on the ground who we could trust. It wasn’t totally blind. It was well thought through and curated, yet completely open.

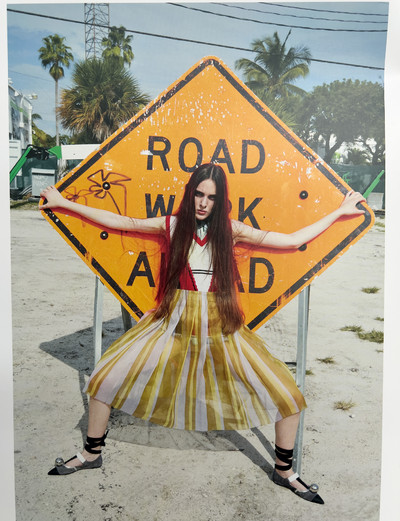

Dennis: Juergen, we have to mention the two places where we were not invited. We went to the Cannes Film Festival even though we had no official accreditations. We couldn’t go in anywhere, but we did these crazy photographs on the fringes of everything…

Juergen: It was way more exciting than being there officially!

Dennis: And we went to Art Basel in Miami. Same thing – no passes, no accreditations, and we just did everything on the fringe. There is that great photo of the two bodybuilders holding the pocket bags. That could not have happened had we been part of the establishment. It was a way of saying, ‘You know this whole hierarchy of art fairs, previews and special previews? We’d rather go uninvited…’ And I’ll just put this in and then shut up: a fashion shoot isn’t just about the exercise of shooting clothes. It is, in a sense, a family: we go to dinner, we talk and we might have a drink, and it forms a real connection that is absolutely reflected in the pictures.

Juergen: I totally agree. We talk over dinner, we have an idea about something, and then we might see something and go do a picture at 11.30 at night.

As you say, that’s often reflected in the pictures.

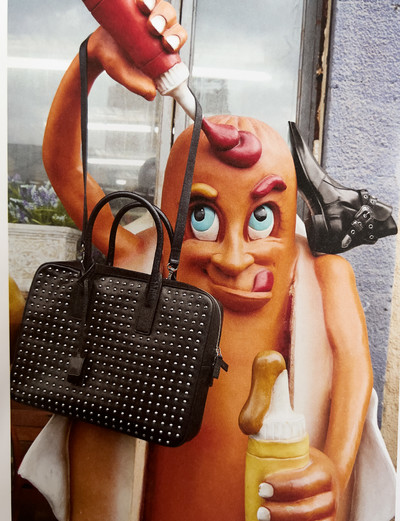

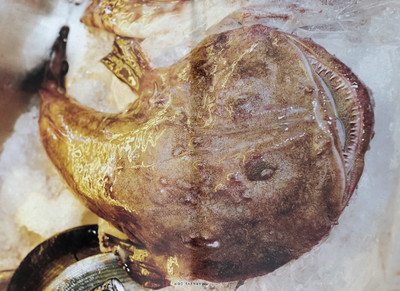

Juergen: When you asked before about the direction from Barneys, the other interesting thing was that we had to shoot still lifes, like a pair of shoes or some handbags. It can be the most boring thing, but Dennis was so brilliant. We work so well together that we even got excited making those pictures.

Dennis: One of the highlights of my career was, and still is, I think, that Juergen 100% trusted me to set up the still lifes on these shoots. It would take a little while as I would be playing with all the accessories, and I would go somewhere and take a bag and just put it on the floor, and 9 times out of 10, that is what we shot. It was my only period of being what you could call a stylist, but it really worked…

‘Why are campaigns so painstakingly boring? And overproduced – which is even worse! I might get into trouble for saying this, but who cares?’

Looking at the Miami pictures, I can see a link between them and the windows you were doing at Barneys.

Dennis: Yes, 100%! When I think of those pictures I also think about what was, and still is, missing from so many campaigns –this kind of mad humour. Why are all these campaigns so painstakingly boring? And not only boring, but overproduced – which is even worse! I know I might get into trouble for saying this, but at this point, who cares?

How many catalogues did you end up doing together for Barneys?

Juergen: We did 11 in total.

Dennis: We did it for six years.

Was it already clear from the start what the end goal would be for these pictures? Was it all about the print catalogue? Who was that destined for, like, was it being mailed out to customers across the US?

Dennis: Barneys never advertised; we only made these very well-produced catalogues using the pictures. We only made a certain number and we only shipped them to our customers, so no one really saw these pictures because they were not widely distributed.

Juergen: From Barneys’ point of view, I think these catalogues were very important for the designers themselves, and that helped Barneys’ commercial buyers get the best products. Fashion designers or their PRs would all come to me and said, ‘Oh my God, your Barneys catalogue is genius; every time it is so fresh.’ So I think they helped Barneys in that way.

It gave Barneys fashion credibility.

Dennis: We mostly shot men’s fashion and I really think the one true genius at Barneys was the menswear buyer, Jay Bell, who now happens to work for Thom Browne. We’re not talking men’s suiting; that wasn’t him. Jay, for example, was buying Off-White super early. He knew everything, and he was so supportive and loved what we did with the clothes. If you are lucky you can cut through the bureaucracy and work with people who believe in you. In this case, they did, and as Juergen said, there was this small insider distribution.

How small? Because everyone in the industry did see it.

Dennis: They were first of all sent to our customers and to the brands who we bought. But I don’t think they were sent to Europe; it was too expensive. It was small but with a big impact because, as Juergen says, important designers got to see them.

What was the reaction internally to the catalogues? Presumably it was positive otherwise you wouldn’t have made it an ongoing series.

Dennis: Well, I’ll tell another story without naming any names, but I remember one day I was at Barneys and one of the buyers – not Jay Bell – just didn’t get what we were doing, like really didn’t get it. She said to me, ‘Dennis, why can’t you use “pretty girls”?’ I swear! I think I had an interior meltdown; it made me really depressed. This was a major buyer at Barneys, and she is asking me why we can’t use ‘pretty girls’. I said, ‘Do you go to shows?’ Of course she went to shows. ‘Do you look on the runway, do you look at magazines?’ I said. ‘What is a “pretty girl”?’ That was a culture I had to deal with at that time, even in Barneys.

I can well imagine.

Dennis: But in a weird way, there was, and still is, a little more freedom with men’s fashion. And the great growth during my time at Barneys was in men’s.

Juergen: That also started when menswear became much more interesting. It made a real push.

Dennis: There were designers who were really challenging men’s style codes, but there were still those who were just a white suit, a black suit, a grey suit. I knew that Juergen was not the kind of photographer who would look at a men’s suit and think, ‘Oh my god, how am I going to shoot that? How am I going to light it?’ In fact, I’ve never really had that kind of thinking about shooting fashion. I would always say, ‘Well, you know, William Eggleston didn’t style his subjects. They wore what they wore and what they wore was just a part of them. The picture wasn’t about that.’ Similarly, Juergen was someone I never worried about; he wasn’t going to be like, ‘Wow this is a boring brown suit’, because a boring brown suit can be great for our picture.

‘While every other art form was engaging with contemporary culture, fashion remained in its own parochial elitist world. That couldn’t and didn’t last.’

Do you think in some way you were reacting against something wider in the industry?

Dennis: At the time, the world was so small. There was, and still is, a parochial approach in the fashion world; it’s so far behind television, movies, music. Even when I was at W, I kept saying, ‘Oh my god, fashion imagery is like living in a Leave It to Beaver world.’ While every other art form was engaging with contemporary culture, fashion was isolated in its own parochial elitist world, along with everyone in it. That couldn’t and didn’t last. It was never bound to last. I never accepted that, and on a personal level, I couldn’t buy into that.

Juergen: If I think of fashion photography or fashion advertising, I want it to be alive. I want you to feel a person, their smile, their sadness, their energy, that they are happy to be wearing a sexy outfit or they are cold when they wear a coat because that is why you wear a coat. Fashion, for me, should be fun – it should be light and happy, but fashion photography is so deadly serious and manufactured. It just doesn’t live in real life. My thing was that I wanted to bring it into the world, like in Albania, and make it more human. For me, photography was always about these models coming to do the shoot and being able to see their skin and the colour of their hair – not some airbrushed shit with a handbag shoved in their face. It is about being alive – that is what it is.