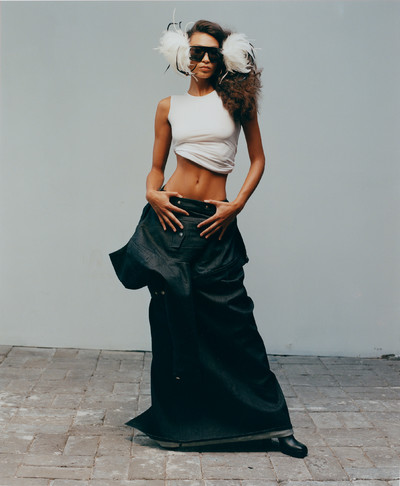

Raul Lopez opens up about the ‘urban dystopia’ of his childhood in 1990s Williamsburg, the salvation he found through the ballroom scene, and how he’s turned Luar into the hottest New York fashion label in years.

Interview by Rana Toofanian

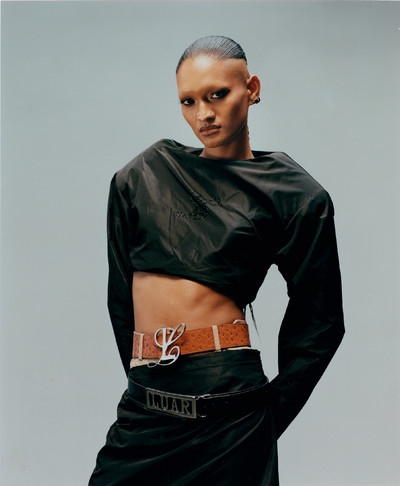

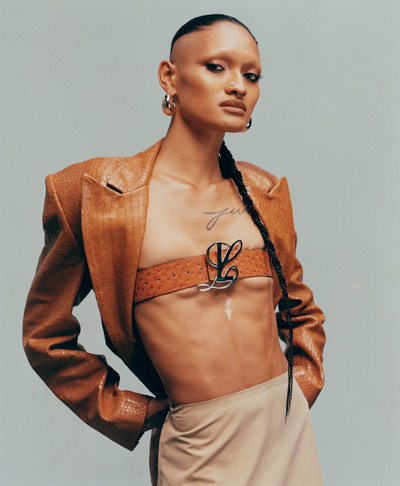

Photographs by Philip-Daniel Ducasse

Styling by Kyle Luu

Raul Lopez opens up about the ‘urban dystopia’ of his childhood in 1990s Williamsburg, the salvation he found through the ballroom scene, and how he’s turned Luar into the hottest New York fashion label in years.

‘Premium trash.’ That’s how designer Raul Lopez describes his personal style. Yet his reverse namesake label, Luar, which is upending industry hierarchies by prioritizing authenticity and community over status quo, has become one of the most exciting brands to show at New York Fashion Week in years.

Lopez was already a fashion insider when he launched Luar over a decade ago. As a teenager he was part of New York’s ballroom scene, a Black- and Latino-led LGBTQIA+ subculture that organizes beauty pageants and voguing competitions for community members. It was here that, aged 16, he met Shayne Oliver. A friendship quickly formed, catalysed by their mutual appreciation for each other’s outfits, and in 2006 the duo founded Hood By Air with the then-innovative aim of bridging the gap between streetwear and luxury fashion. In 2010, before Hood By Air’s rapid rise to success, Lopez left the brand and travelled to the Dominican Republic to reconnect with his roots.

Having spent months observing the ways local Dominican men and women dressed, Lopez founded Luar in 2011 as a way to celebrate his Hispanic heritage. Luar – then named Luar Zepol – quickly became synonymous with a combination of redefined basics and sharp tailoring, two design staples that were all the more pronounced in the brand’s triumphant Spring/Summer 2023 collection. Models in double-breasted jackets with oversized lapels, dropped-waist silk dresses, nylon tech jackets, and bold-shouldered blazers walked down the runway in a powerful tribute to Lopez’s family get-togethers in Brooklyn at which aunts and uncles would dress in their finest ensembles under unassuming sports jackets. For Lopez, the brand is simply a way of, in his words, giving back ‘to these people who have influenced my life’. It hasn’t always been smooth sailing for Luar or Lopez, however. He has been forced to put the brand on hold twice since 2011, most recently in 2019 as a result of mental burnout. The break, it seems, did his vision good. Luar has recently topped the lists of New York fashion’s buzziest names not least because of its popular Ana bag, which, in November, helped earn Lopez the American Accessory Designer of the Year Award at the 2022 CFDA Fashion Awards.

Following the launch of the Spring/Summer 2023 collection and shortly after Lopez was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people in the world, the designer sat down with System to discuss the influence of his Dominican roots, ballroom culture, and how people-watching has shaped the star-studded evolution of Luar.

Rana Toofanian: You were born and raised in Brooklyn?

Raul Lopez: In Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I still live in the same building I grew up in.

Describe Brooklyn in the 1990s. What was life like?

It was a beautiful, urban dystopia. It was what we knew, and what was around us. I really loved it. I’m first generation, and it was great to see people older than me hustle and build new lives for everyone coming after them. There was a sense of survival mode that pushed you to seek things out. Even in terms of clothing, there was the challenge of trying to look good in a shitty dump. There’s a really good documentary filmed in 1984 called Los Sures – which means South Williamsburg – about the neighbourhood, which was then predominantly Latino.

Tell me a bit about your upbringing.

I come from a Dominican Republic Latino household. It was survival of the fittest – my dad worked as the super in the building I grew up in, and my mom worked in factories in the Garment District alongside her siblings and other relatives. This upbringing has influenced my DNA, and the DNA of the brand itself, in that the hustle and bustle and grind is to make something beautiful. I hustle in the same way with Luar as my family did to give us this beautiful life. I had a crazy upbringing of being this gay boy stuck in an era where you weren’t allowed to be yourself, living in fear and acting on it by building a [mental] wall in my everyday life. I also developed a tough skin in order to walk through the streets and hold my own – that was what the neighbourhood required, too. I was not allowed to relish the gay manifestations of the kids who were running around, although it was very rare to see [overtly] gay people back then. It’s the way I was brought up and the way I perceived my neighbourhood that made me the person that I am today. It was tough, but I made it work despite all the noes I was met with.

‘The sense of survival pushed you to seek things out. Even in terms of clothing, there was the challenge of trying to look good in a shitty dump.’

You mentioned that your mother and grandmother worked in the Garment District. What were your earliest memories of fashion, and what access to and awareness of it did you have back then?

I watched my mom and these women, these central figures in my household, get dressed as a way for them to feel good about this really shit life they were living in this urban dystopia. The mindset was like, ‘I may live here, but I am going to look good’. They were always dressed up – always! Even on a regular day, they would wear really beautiful, oversized sweaters, and well-tailored pants. My mom wore heels every day, and my Aunt Sue and my grandmother were always telling me that, when you wake up, you need to do your face and your hair before your husband sees you. It was super old school, but I found it really chic. Even the prostitutes in my neighbourhood wore these insane outfits. I was always blown away like, ‘Goddam, what the hell?’ I think it all stems from the matriarchy in my family and how they carry themselves. The way they dressed and presented themselves to everyone was luxury.

When did you realize you wanted to design and make clothes for a living?

We would have these family functions when things would really go off. There were weddings, but it was at the quinceañeras and ‘sweet sixteen’ parties where everyone was decked out. Then there were my family reunions, which took place every month, which would take it to another level. My family would get these really beautiful garments from nowhere – these guys didn’t have any money, but they were trying to live this American luxury dream. It was a dump of a place, but they always put on their best looks. That was when I was like, ‘I want to make stuff; I want women or men to like this; I want to make people feel good when they wear my stuff.’ It wasn’t about having everyone say, ‘Oh you look fab’, but rather about making me feel and fit into the status quo of what America feels is luxury. Later, I wasn’t actually allowed to go to fashion school, so I taught myself. There was an industrial sewing machine in my house because the women in my family were either making clothing for us or creating curtains and pillow cases. In that sense I was always exposed to sewing, even if I wasn’t allowed to partake in it. That is also how I figured out my way of rebelling. Instead of doing drugs, like any typical teenage rebellion, I would go to the library, which was like spit in their faces. I’d go behind their backs and sneak into the Fashion Institute of Technology or Parsons to try and gain knowledge. I would also rip pages out of textbooks when I was in high school, which was my only opportunity to see what goes into the physical construction of clothes. That was my thing. I clearly remember my first time seeing a Lacroix show. It was on Fashion TV in New York, a channel I wasn’t allowed to watch. For some reason, I got to watch this particular show and I was so blown away. I was like, ‘Woah, this is exactly who I am.’

‘Instead of doing drugs, like any typical teenage rebellion, I’d sneak into the FIT library to gain knowledge. That was like spitting in their faces.’

How did this interest you had in fashion and dressing up translate into your everyday life?

I always wanted to stand out. When I was a kid in elementary school, I had to wear a suit every day. If you were to ask my mom, she would tell you I was called ‘Little Tie’ back then because I always wore a suit and tie. If I hadn’t had a suit, I wouldn’t have gone to school! I think that was when my mom was like, ‘OK, we know you’re with the girls.’ My brother, my cousins – no one else was like that; it was just me. I always wanted to stand out. I started designing in junior high school. I wanted to fit in as the popular kid, but I always liked standing out, too. Obviously people back then knew I was gay, but they weren’t saying anything because I was the cool kid. At that time, I was chopping up stuff I was getting from the thrifts, cutting the leg off a pair of Girbaud jeans and turning it into a sleeve of a white Hanes T-shirt. That still feels very Luar; my DNA is still there. I was buying designer stuff, too. I was ironing for money in my building because I wanted to buy these things I was seeing on TV, and I knew my family couldn’t get them for me. So, I just started ironing after my mom gave me an iron and an ironing board. I would be watching Saved by the Bell, and neighbours would come by to drop a bag off. During the week I was making around $600, which was crazy in that era.

To this day you still love to get dressed up – and you have a really distinctive personal style.

It all stems from my family, especially my mom. They dressed up for themselves and not for anyone else. So, I really feel that I dress for myself, to be a conversation piece, to make people uncomfortable when they are around me. It’s a way of not saying something, yet saying something.

How would you describe your personal style now?

Premium trash.

‘I was cutting the leg off a pair of Girbaud jeans and turning it into a sleeve of a white Hanes T-shirt. That still feels very Luar. It’s my DNA.’

You describe yourself as a ‘granny’ a lot of the time, which really seems your thing. What do you mean by granny?

It’s a state of mind; it’s about how you carry yourself. Being a granny has nothing to do with age. A granny just wants to chill, have dinner, look cute, and hang out with people. It doesn’t mean you’re 60 or 70 years old, which I think is what a lot of people think granny means. Nowadays, kids come to me, talk to me, and ask me questions. Even older heads come to me to ask me things – and vice versa. This is why I got deemed to be a granny, which is a thing in ballroom culture, because a lot of people keep asking me questions for whatever the reason is.

Is a granny a trendsetter?

Period.

After high school, you met Shayne Oliver and co-founded Hood By Air. How did that happen?

A lot of people in high school were asking me to make stuff for them. Then, when I was introduced to ballroom and Christopher Street, I saw people making their own things in ways that made me think, ‘Damn, this is fab’. When I met Shayne, he was on the same wavelength as myself, and we clicked because we came from the same upbringing. We were both searching for another status quo and looking for ways to revolutionize and shake things up. Because Shayne also dresses to make people uncomfortable. At the time, my life was about going to ballroom and seeing people put on these amazing looks, and then I met Shayne, who wanted to do the same thing as me. We became really close, and so we were like, ‘We should just do our own thing.’

Tell me a bit about Christopher Street and ballroom back then? What role did that play in your life?

My entry into the scene was more about me trying to find a way to escape. I first saw Christopher Street when I used to come down the Westside Highway from my grandmother’s house in the Bronx to go back to Brooklyn. There was a stop light between Christopher Street and West Street that was literally right at the entrance of the pier, where I would see all the drag and trans girls and butch queen boys, walking and going across the street. I was like, ‘What the hell is this?’ Then, I started talking to this dude on AOL chatrooms and they told me about it. So, I went down there and that’s how I discovered Christopher Street. That’s where I found a lot of my friends who are still my friends to this day. That’s where I met Shayne – he was like 13, and I was 15. That’s how I found ballroom. These are the families you chose. They help you out and it’s fun. Obviously you fight and do the whole thing, too. Ballroom really moulded me – from the way I carry myself, to the way I look, to the way I always have to look good, smell good. You always have to come through to shut it down everywhere I go. Ballroom really be moulding the girls into this type of mindset.

You left Hood by Air in 2010. What did you take away from your time there?

Hood By Air was a stepping stone; it was a revolutionary thing where we both were building this beautiful, tangible, realistic story into fruition. It taught me a lot about construction, actual fashion things I never got to learn in school. That also meant interning for myself. In this sense, I think Hood By Air taught me to do a lot of things that I still do to this day. For example, it helped me develop my own style, and to find my own voice.

You don’t come from a traditional fashion background, by that I mean institutions like Parsons or Fashion Institute of Technology. Has your unconventional route into the industry ever been the cause of any anxiety?

No, because I am from here. For me, my inspiration doesn’t always come from books – it comes from what the everyday person wears. I didn’t need someone to tell me what to do and how to do it. That’s what the library is for. I need something hands-on; I need tangible; I need to be in it. That is why I was sneaking into the library at FIT.

After you left Hood by Air, I read that you went to the Dominican Republic to reconnect with your culture. That led to the inception of Luar. Can you tell me about that?

I was thinking about the ways in which I could give back to the people who had influenced my life. The trip was also a study of questions like: ‘Why do I act like this? Why do I dress like this? Why are my mannerisms like this? Why do I talk like this? Why do I carry myself like this?’ It was almost like a case study because although I come from a Dominican family, I was born and raised in New York, and I wanted to see how actual Dominicans lived. I wanted to understand the reasons – other than just money – as to why they leave their homes to come here. I wanted to see how these people who don’t come from spoon-fed families survive and dress themselves for everyday purposes and events. And also, I wanted to start working with Dominican tailors because there are really amazing ones there, and I just wanted to give back. I wanted to give people an opportunity just like they gave me an opportunity.

What did you learn from that experience?

Oh my God, I learned a lot. It was great. It was amazing to see how they make outfits from nothing. The men wear women’s garments and bags – like Lil Uzi Vert who has been on that wave. Even when the girls come down they are like, ‘Oh, I get it.’ I am like, ‘Yes, they are always ahead.’ For some weird reason, their style and the way they make things are always so progressively ahead of America. The whole fluid look, for example. Girl, they have been on that!

You came back from that trip, and launched your own namesake label, Luar Zepol. You’ve said in the past that that was at times a real struggle, especially when it came to keeping the business afloat – eventually leading you to burn out in 2019.

I was funding myself with unemployment checks, and I was like, ‘OK, now I need to do my thing and figure out how I can share my story.’ I was starting from scratch again, and trying to figure out how to step away from the shadow of Hood By Air and be recognized for my own thing and my own brand. To me, that was the biggest struggle for a while, figuring out my own identity and style within this space. I was doing a lot of studying, visiting a lot of libraries, and going to these neighbourhoods in the Dominican Republic where I was recording what people were wearing with my mind. A lot of the looks in the early stages of my collection resemble the boys and the girls in DR. As a young designer, you think you know it all, you can be an artist, you can do whatever you want to do – but how do you make yourself sustainable? I wasn’t always in the right headspace. I was thinking about doing shows and making clothes to prove to people that I was a designer, but I wasn’t thinking about how I could make money off my work. I was so stuck on this hamster wheel of fashion that, once I jumped off, I was so mentally exhausted that I needed to take a break and get myself together.

You then put the brand on pause that same year.

Yeah, and I told myself that if I ever wanted to come back, I needed to do it right. I was in such a dark place for so long. I couldn’t relish all my accomplishments, even though people were recognizing me, like, ‘Oh, he did a show and some press.’ Once I took a break and got myself together both mentally, physically and emotionally, you could tell through the collections that I was in a happier place. These stories really mean things to me because they strike these chords about who I am today.

Where do you draw inspiration from?

Oh, I love the street; I love people-watching; I love what people think is really ugly. I am like a chameleon; one day I can look super masc and then another I’ll be super femme. Or both depending on whatever I wake up to find on my floor. I’m intrigued by people who dress themselves through necessity and not out of habit. When I see, even in the Dominican Republic, people who want to emulate certain looks, they actually are doing it from thrifts, taking the fabrics to a tailor to mimic what they’ve seen and liked. It is all out of necessity. People come from poverty, and so it’s not about the label, but rather about how you look and how you present yourself.

You mentioned ballroom earlier, too.

Me showing my collections is linked to ballroom where there is this obsession with putting together a whole production and a show to get your prize. That has been embedded in me because I love to put on a show – I am old school with things like that. Other people are like, ‘Oh, I want to have a [static] presentation.’ And I am like, ‘I can never do a presentation like that; I would rather not show.’ I love the accessories, the hair, the make-up, the whole thing – bringing people together in a space and hanging out. The same thing goes with ballroom where you hang out and see people you haven’t seen for a long time while watching these performances. That is how my show is.

What is the value of fashion to you? There has been a lot of struggle on your journey so far. What has kept you motivated to do this work?

It’s the only way I can be. I would go crazy otherwise, I need some kind of outlet. Some people use a journal, a diary, voice memos – I have to make clothes. This is the only way I know how to express myself and let my story be told. These clothes are just like pages in my journal. Each garment has a specific meaning and is part of this chapter in my life. Luar is just a reflection of myself, and these are stories that I am bringing into fruition for people to experience and interpret in their own way.

‘Luar is a reflection of myself, and these clothes are stories that I am bringing into fruition for people to experience and interpret in their own way.’

What has been a transcendent moment for you so far?

What makes me really feel like a designer is right after the show when I see my work coming to fruition from sketches and drapes. That is when I feel my most authentic self. Even though I am drained and dead, it’s like when you are writing a book and then boom you are done, and you close it, and you’re like, ‘finally’ – but then everyone else reads it and you know they love it. That to me is the moment right after the show.

Are you optimistic about the future of Luar?

I know it’s going to be good because I feel I have now learned more about the business side of running the brand. I’ve also learned how to manage myself and my mental health while balancing my work life and my personal life as opposed to separating the two, which I think people try to do and which is just a shit show.

As a young designer, you have had no shortage of press opportunities. There is a lot of interest in the brand, and the Ana bag is a really great example of you taking Luar to the next level of commercial success. But what are the biggest obstacles facing you?

Yes, 100%, that is the only way you can continue sharing your stories and your art. Figuring out what pieces are commercially successful is what allows me to keep selling my story. I know what I want to do. I am an accessories person: I love accessories and I think building this whole empire around accessories is what will help me tell my story and create my collections. As a young designer you really want to run the show and wear every hat. You want to do everything yourself because you are scared that your name will end up crucified if things go wrong. So, the biggest challenge is learning how to take your hat off and let other people wear it as well. Then, just trust the process. I feel like you have to sift through a lot of people to find the right ones who are ready to ride or die for you. This is the same with all creators and designers and artists; we are scared of letting people do things for us. But I find that it’s once you learn to let things go a bit that you really start growing.

Make-up: Raisa Flowers.

Hair: Joey George.

Production: FAMILY Projects, Olivia Gouveia.

Lighting director: Jupiter Jones.

Photography assistant: Nikolai Hagen.

Styling assistant: Tonya Huynh.

Production assistant: Myles Gouveia.