Interview by Jonathan Wingfield

‘The whole idea of fashion’s initial impulses has gotten bigger – the illusion got bigger, the aspiration got bigger. Now, the aspiration isn’t simply to have the little dress or the little designer bag, it’s to have the private jet to walk onto holding that bag or wearing that dress.’

In January of this year, the much-loved and respected writer and fashion critic Tim Blanks posted a picture on Instagram of the facade of Parisian restaurant Le Castiglione. It was accompanied by a lengthy caption, extracts of which read as follows:

‘Dear Casti, for three decades, you have been my canteen during countless fashion weeks. Breakfast, lunch, late night and every hour in between, you have fed and watered me and just about everyone I know. You were always the best place to eat on my own (table for one, in the window). And now you have to go because your whole corner is being developed as a Gucci superstore. Just like the Vuitton one over the road. Developers! Meh! What do they know about tarte fine aux pommes (I must have eaten hundreds of those) … I want to thank you, dear Casti, for being my home, my haven, my red velvet womb in the fashion week whirlwind. Mournfully but gratefully yours, Tim. (RIP @lecastiglione, 235 Rue Saint-Honoré, 75001 Paris.)’

The post triggered an immediate and affecting response. Almost 500 people commented, many of them industry folks, young and old alike, local and international. The news, and its broader sentiment, had clearly struck a chord. Not so much, one suspects, over the closure of the restaurant itself or even about it being supplanted by a luxury-brand megastore, but how hugely symbolic the development seemed to be of an industry that, over the past decade, has swollen, accelerated, shifted its sights, and in many cases, grown far bigger than even the most seasoned business forecasters could have imagined.

These changes have been centred largely upon the unrelenting dominance of Paris’s luxury fashion houses and conglomerates. And, of course, it would be disingenuous and short-sighted not to acknowledge the many benefits associated with all the profits and expansion. The luxury fashion industry now makes a significant contribution to France’s GDP, and employs over a million people across the country, enabling artisanal skills to survive and small businesses to be secured for the foreseeable future. And, during fashion’s seasonal fanfare, Paris Fashion Week, the vibrations of a cash-rich industry can be felt across the city, in booked-out restaurant and hotels, as well as the stifling traffic jams caused by the fleets of luxury vehicles at the disposal of the assembled attendees.

For System, Blanks’ words both resonated and exhumed the memory of a comment that his fellow writer and esteemed critic Cathy Horyn had once mentioned to us in passing. ‘Towards the end of each fashion week, since forever, Timmy and I will sit in the Castiglione, over dinner, maybe a drink, too, and discuss it all. Everything.’ As a publication that aims to capture the dialogues at the heart of the industry, the prospect of eavesdropping such a conversation has long-remained tantalizing. Not least because Blanks and Horyn’s commentary (him for the Business of Fashion, her for The Cut) represents a level of experience and authority that’s always been essential to fashion’s evaluation and progress – even if it can sometimes feel a little undervalued or simply eclipsed by other forms of expression, other ‘content’, other industry needs.

With System’s ten-year anniversary providing the chance to re-evaluate fashion’s recent history, we were keen to bring Blanks and Horyn together in conversation. If not in the Castiglione, then during a series of Zoom and phone calls, and in-person exchanges, following the conclusion of the Autumn/Winter 2023-2024 season. To cast their all-seeing eye over the ‘big picture’. Of Paris. Of Paris Fashion Week. Of the impacts the industry at large is having on design and designers. Of what it means to run a multi-billion-euro fashion business. As well as the broader effects that fashion is having on the global climate crisis, social inequality, and the future of, well, everything. But just before things took an existential turn, there was just time to reappraise Le Castiglione’s lunch menu…

London and New York,

14 March, 19 April, 25 April 2023

Cathy Horyn: I started going in the early nineties, when I was at the Washington Post. You’d go in there and there’d be guys like Burt Tansky from Neiman Marcus and Mel Jacobs of Saks – all those American retail CEOs – having breakfast with their wives. They probably stayed at the Ritz or the Meurice, and went to the Castiglione because the food was good, not pricey, and the owner, Pierre, was so hospitable. You’d never see them in there later in the day.

Tim Blanks: All the Castiglione waiters were such roués, like that guy, Augustin. Breakfast was business-y, but at night the vibe changed and you felt like something might happen later.

Cathy: Lunchtime was only neighbourhood Parisians. I remember [Pierre’s son] Fabrice introducing me to a guy who worked for the Crazy Horse. The bar would be packed; the tables would be packed. I never went upstairs, that wasn’t my thing, except with you.

Tim: I only ever went upstairs, except for that little table for one, downstairs at the front, which was perfect for having half a dozen Gillardeau oysters, the saumon à l’unilatérale, and baba au rhum for dessert. Always.

Who’d have thought Tim’s lunch habits were so emblematic of Paris Fashion Week?

Tim: [Laughs] An army marches on its stomach, so for me, Paris Fashion Week can be charted in the places where you eat. It’s social history! Think about Kinugawa on Rue du Mont-Thabor; it was such a great fashion pit stop; you’d go all the time, even on your own and sit at that little sushi bar at the back. Then all of a sudden it got all zhuzhed up, and became all, ‘Do you have a reservation, sir?’ You couldn’t just show up any more. It was little things like that that made you realize how the city was changing.

What do you think triggered those changes?

Tim: The Costes explosion in the mid-nineties certainly had a big impact, I think. Which perhaps made Paris become more international in a way. It seems almost paradoxical to describe it like that, but I guess it was the Costes-ization of Paris. The menu at the Castiglione started looking like a Costes menu – everyone eating those little spring rolls that you wrap in lettuce – there was even a rumour that the Costes had bought the Castiglione.

Cathy: The whole explosion of the Castiglione as a fashion canteen coincided with the development of Rue Saint-Honoré as a retail strip of trendy big brands. Before that it was more charming, with those vintage jewellery shops, and Goyard was there…

Tim: …and Chantal Thomass…

Cathy: …and a lot of those mom-and-pop shops. There are still a few left. [Legendary lingerie house] Cadolle still has its headquarters on Rue Saint-Honoré. I remember writing about Le Castiglione for a New York Times travel piece in the early 2000s; about how Rue Saint-Honoré had become a fashion destination, and was drawing an international crowd, certainly since the opening of Colette [in 1997].

Tim: It felt like an adoption of that [Ian] Schrager ‘boutique hotel’ culture, of Morgans and the Royalton. It was the boutique-ing of Paris, which is a bit weird because Paris always had ‘boutiques’, but maybe it was just generic boutique-ing, the Costes-ization of all those restaurants they opened.

‘Paris fashion always seemed a bit closed, a bit square, until its defences were broken down by Galliano and McQueen heading up the big houses.’

Interestingly, at the same time in the late nineties, you had Keith McNally’s restaurants opening in New York, like Pastis, which had a faux-distressed century-old Parisian tobacco smoke effect on its ceiling. These days, when you go to somewhere like the Café Charlot in the Marais, it feels like they’ve taken their cues more from Pastis. It’s old-French-café style, pastiched in New York, and then transposed back to Paris as a pastiche of the pastiche of its own heritage. It’s hospitality gone post-post-modern bonkers. And you could say there is a bit of that going on in fashion today, with international brands like The Row or Victoria Beckham, drawn to physically showing in Paris, tapping into those codes of Parisian fashion, and then selling back a slightly watered-down version to an international clientele. We’ll probably see a Parisian brand emerging soon that replicates the style of The Row, as opposed to replicating the original source of, say, Hermès, which is on its doorstep.

Tim: Yes, it’s kind of like how the Beatles took R&B and sold it back to America. It’s the way pop culture works, although Paris has historically been so much more resistant; the Parisians are so much more intractable in their self-belief than other people in big cities. I mean, they definitely embraced jazz culture from America, but Paris fashion always seemed a bit closed, compared to London and New York. Maybe a bit square, until its defences were broken down by Galliano, McQueen, Tom Ford, Michael Kors, Narciso Rodriguez and Marc Jacobs heading up the big luxury houses. And so, for those people, Paris becomes this stamp of legitimacy on a fashion business. It probably always will be for a designer. Even as fashion becomes much more international – with places like Nairobi and São Paulo becoming hubs – to show in Paris is the apex. And I think that’s become consolidated over the last few decades. It didn’t just happen overnight. It was an orchestrated situation, I would imagine, by the Chambre Syndicale.

It’s a bit like Hollywood. People are increasingly aware of fantastic Iranian cinema, Korean cinema, and obviously European cinema, but Hollywood just has its own cachet, because it’s mythologized its own existence since day one.

Tim: I actually think fashion has consolidated everything else in the city. You come here for the fashion, but you now get a full cultural 360, which has coincided with the growth of LVMH and Kering as symbols of the big-ness of Paris, the centrality of it. Something like contemporary art in Paris is increasingly defined by Arnault’s Fondation Vuitton or the Pinault Collection at the Bourse de Commerce.

So Paris has become a commodity of fashion.

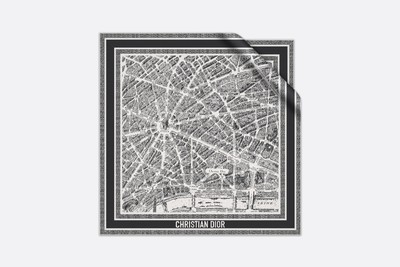

Tim: Maria Grazia did a scarf with an old print of Paris, which had all the touristy landmarks on it, and the mammoth Dior boutique was printed on the scarf as well, like a tourist destination.

Dior, Plan de Paris 90 Square Scarf.

Photo: Courtesy of Christian Dior.

The self-mythologizing of, ‘We’ll just pop ourselves between the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre.’

Tim: Self-mythologizing, that’s what it is. Paris seems to be the best at it, probably because they chopped their king and queen’s heads off. I don’t know for sure how the Macron situation over the past few weeks has affected the mood, but the city feels newly confident; certainly in fashion, there is an unshakable sense that Paris is the centre of the universe. You see Paris as a fashion theme park more than you do in other cities: you have the huge Vuitton stores; you have places like the Place Vendôme, which are like natural amphitheatres for fashion. You have the renovation of the Ritz, even the Langosteria restaurant in the Cheval Blanc is about the elevation of fashion, of creating a Parisian outpost of the most fashionable restaurant in Milan but making it better than the original. It’s almost like a ‘fuck you’.

Cathy: What we are seeing is the power of LVMH and Kering, as well as the power of branding. And concurrently to that, you see the decline of cafes in Paris. These days I’m more attracted to Le Petit Vendôme again because it reminds me of old Paris; it’s like a friendly dive café; it has a great cheese platter, and it represents that simpler Parisian lifestyle.

‘Of all the fashion capitals, Paris has been the best at its self-mythology. Probably because they chopped their king and queen’s heads off.’

Doesn’t that kind of sentimental nostalgia go against fashion’s natural state of progress? Aren’t those just the inevitable changes that define cities?

Cathy: I was talking to Jonathan Anderson and [stylist] Benjamin Bruno about this last summer because Loewe had just moved from the Left Bank – Place Saint-Sulpice, which was always associated with Saint Laurent, and with Catherine Deneuve who lives there – to Rue Scribe, between the Opéra and the Madeleine. Benjamin was saying it’s such an uncool neighbourhood, and I was like, ‘But you’re in the heart of 19th-century Paris; this is where it all happened. [Charles] Worth was round the corner.’ I find it really reassuring that in Paris, like in New York City, the city just constantly changes, and if you love history and the evolution of things, you can embrace most of these changes and understand them as part of a bigger picture.

What about the scale of the industry, and this idea that there’s more of everything now, especially in Paris. Are there more shows on the schedule now, or is that a popular misconception?

Tim: If you look at a calendar from 1990 – I recently found all my old schedules for Fashion File – and the amount of stuff we did in one day! The number of interviews we did, skating around with a camera crew…

Cathy: I think you’re right, Tim. I’ve always said what I really like about Paris, over the other cities, is that they know who they are. The Chambre Syndicale has been in existence for 150 years and they run that schedule really well. If you look back to the early nineties, the schedule was just as crowded; we probably went to more shows at the time. And I do think we went to better shows then, too. We saw not only the established houses like Chanel, Saint Laurent or Dior, but we also saw Mugler, Gaultier, Helmut Lang, Margiela. You had a feast.

Tim: Martine Sitbon…

Cathy: There were so many, and they were all great. That whole pattern continued through the eighties, well into the nineties, and the early 2000s. You were getting a lot of value for your time when you came to the Paris shows. Although I’d probably say you got the same value in New York at that time.

Tim: I don’t know if that was down to more quality control or if they were just better designers, or if the Chambre Syndicale’s entry criteria for fashion week were more stringent.

Cathy, you just said you felt the shows were better 20-30 years ago. So, what is your memory of the week that’s just taken place. Did you feel let down? Has there been a lapse in quality control?

Cathy: The fundamental shift is down to branding and marketing. Fashion’s no longer really about design as much, and yet I think that is what we’re all hungering for. I don’t mean fantasy, I just mean more really good design that moves the needle. I think some of us still believe that it can exist, if you look at Jonathan Anderson at Loewe or Demna at Balenciaga, and probably a few others. I think what we’re seeing now is more about these big brands expressing their power and domination. Chanel’s a $17-billion brand today, Dior is multiple billions, and they have these huge shows. Look at Dior in the Tuileries; it seems to have gotten bigger and bigger and it’s got all these K-pop stars. It’s just about something else today; it is not really about innovation. Or it just serves so many other purposes today, whether that’s social media or the influencers, all kinds of other things.

‘The fundamental shift is down to branding. Fashion’s no longer really about design as much, and yet I think that is what we’re all hungering for.’

Will that shift continue?

Cathy: Well, I think what System is capturing with this ten-year issue is that fashion is in some sort of whirlpool right now. You can either go this way or that way, but it is just spinning right now, and it could head in any direction. With Demna or Jonathan Anderson or a few other people, we’re seeing the type of values in fashion that we still associate with, say, Prada or Raf [Simons], but, you know, we also have Pharrell coming into Vuitton menswear, and so we’ll probably see more things like that.

There have been mixed reactions to that appointment, even though it’s too early to actually judge anything.

Cathy: Vuitton is such a different beast to everyone else, Vuitton men’s in particular. They communicate across such a huge global platform, and it is not just about the clothes. As long as you have a great leader in there, a great creative force who could come from someplace else, like Pharrell. It is very gutsy to choose him. I think the biggest question is how much time he will commit to being the creative director, because he does so many other things. I am open to the idea that someone like him could come in with a bigger vision of how people want to look. But that is different to what Raf or Nicolas [Ghesquière] are about. Whenever you talk to them – and you could probably include John [Galliano] and Lagerfeld, too, in that tiny core of designers on the inside – you sense these are people who really understand what design is about, and how the historical needle of fashion gets changed by someone, and what really constitutes an original design. Something more than just, ‘Oh, that is a great arrangement of buttons or zippers’; something like a silhouette change or something that represents a fresh expression, and that is what those guys had grown up with and lived with. When you look at Balenciaga under Nicolas in those early seasons, he really did create trends. I think Demna has done the same thing at Balenciaga in the last few years, so for sure that happens. Just not very often. Lagerfeld used to say, ‘You only need three great designers in a decade to make the change.’

‘Lagerfeld used to say, “You only need three great designers in a decade to make the change.” I’d be happy if we had just one right now.’

In his note at the Balenciaga show, Demna wrote, ‘Fashion has become a kind of entertainment, but often that part overshadows the essence of it, which lays in shapes and volumes.’ He had his reasons for saying that, and the context was specific, but he is basically saying what you are alluding to.

Tim: Yes, although I’d say fashion has been a branch of the entertainment industry since the time of the supermodels. That was when fashion started mirroring Hollywood: you had producers, directors, cameramen, and stars. But then, if we’re going with the analogy of the Hollywood studio system, then that will eventually collapse, as it always does. The hegemony will collapse.

Cathy: It is weird because you also have all these massive brands in both Milan and in Paris, and to a degree with Burberry in London, then you have small designers, but that group is shrinking because it is hard to be a small independent designer now. But I agree with Tim, I think the supermodels were integral to that move towards fashion as entertainment – was that 1990?

Tim: The Peter Lindbergh cover was 1990, it was fairly epochal in terms of timing.

Cathy: You got the Alaïa shows and the Versace shows; it was all so riveting to people. But I think if you start looking at the development of Twitter, which launched in 2006, and Instagram in 2010, that is the significant change. Obviously, prior to that you had Tom Ford and Domenico De Sole really cranking up the Gucci Group, acquiring Balenciaga, McQueen and Saint Laurent, while Arnault was doing the same thing with LVMH. It was that whole brand consolidation: putting big money in, getting great talent, like putting Galliano into Dior. Then you have the social-media phenomenon and e-commerce. I remember talking to Tom Ford in 2004, when he had left Gucci, and we were talking about e-commerce for Tom Ford International, and they just weren’t even aware of it yet. It was still such new territory. So many brands, like Chanel and Céline, didn’t want anything to do with e-commerce, as it was seen as down market. So social media and the digital world have just changed everything.

Tim: And the globalization of everything – that you can speak to everywhere with one voice. I do go back to the Hollywood studio-system analogy: they contracted all the best directors and the best stars who were exclusive to one studio; they had global reach, those movies played all over the world. It was when Hollywood was the world’s dream factory. I think we are still in an early phase of development with this, twenty years or whatever it has been. And if the world survives the more critical challenges facing it – like climate change, rather than fashion industry challenges – you might see a reaction, you might see the Marxist dialectic, and the independent voices might re-emerge as a force.

Independent of the big houses?

Tim: Yes, there was an interesting thing happening in China, before the pandemic chaos and confusion, where I understood that fashion-forward consumers in China were seeking out the most arcane Western designers to validate their own taste. So, it was little designers who became coveted, and this was especially being talked about in London when people like Jonathan Saunders and Christopher Kane were starting out. There was a real hunger for the fashion unknown. It’s probably completely reverted back again, but they didn’t seem so caught up in the names that everybody knew.

Cathy: There has been that urge in the last 10 to 15 years to find more independent brands. I mean, there is a wistfulness, or a nostalgia; you see it on Instagram accounts that show late eighties and nineties fashion, the kind that Tim and I remember, things like BodyMap, Vivienne…

Tim: …Katherine Hamnett. She was amazing!

Cathy: There is certainly that nostalgia around, but the reality of a designer today, producing the clothes, getting a slot in a factory, and maintaining a studio somewhere… I mean, you can do it for a decade but then you’re just worn out. And the thing the big companies have is infrastructure and real estate, and they just dominate. I was at the London shows, and I really like this guy from Wales called Paolo Carzana. I was just thinking about him because he’s such a one-off; his set-up is so small, but he is making clothes dyed with vegetables and spice. I love the whole intention of what he is doing, and the fact he doesn’t compromise, but we’ve seen lots of designers out of London with the same good intentions, and we’ve seen how tough it is to carve out a future.

What’s the best-case scenario for someone like him? Could you ever envisage a new Rick Owens-type designer emerging, someone who could grow their business as successfully as he has?

Cathy: Well, you know, Rick has talked about this in the past, and so did McQueen. When you think about what McQueen was in the nineties, it wasn’t a brand yet – he was a designer, and he was barely selling anything, so it was about creating the myth of McQueen.

Tim: He didn’t produce anything for three seasons.

Cathy: He didn’t care; he just wanted to create the things he did. When you think of Rick Owens, and all those years in LA when he was doing those weedy, goth-looking clothes and just being connected to a few stylists. But he too had the time to create the myth of Rick; he also had the support of all those retailers and journalists who loved what he was doing. If you look at the early Rick Owens collections in Paris, they were pretty awful. His basic wearable things were great, but when he was trying to be experimental, it was so cringey, yet over time, he got it together, and he is incredible now. As Rick has said himself, if it wasn’t for the time that he was given – by his partner, by the stores, by the press – he wouldn’t be in business today.

Tim: Do you think the McQueen model of not producing anything for several seasons, and just building a sort of mystique, would still be possible for someone to do now?

Cathy: I don’t think it is impossible. I still believe that if you are talented, if you have the ideas of a Margiela, and in the case of McQueen, you have the incredible Savile Row skills, and you combine that with the vision that he had of women, you have something super powerful. I still think if someone has a great idea, they can do that.

Tim: For me, there are two people from London in the last ten years – Craig [Green] and Jonathan [Anderson], one menswear, one womenswear. It’s funny because Jonathan started as a menswear designer, and after his first collection Sarah [Mower] and I went backstage and told him, ‘You should be doing womenswear!’ Craig is an interesting case, as in someone who hasn’t compromised and who has earned an enormous amount of respect and adulation, and has a following, but you just can’t see how that scales, even now. I mean, what does scaling even mean today? You know, if the fashion industry is preoccupied with issues like sustainability, there is something so fundamentally unsustainable about the idea of fashion. Yet I still sit with people who excitedly tell me, ‘We’re going to be the next billion-dollar business!’ And that feels like a fundamental shift. When I first interviewed Michael Kors, in about 1985, he said, ‘If I’m a million-dollar business, I want to be able to put that million dollars on the table, I want to be as big as I say I am.’ It was such a different reality to this $20-billion chimera, which becomes kind of meaningless, like a cudgel that you beat people with. The scale of these houses has actually become numbing.

‘It’s all these guys – and it is mostly guys – who are executives, and it is almost like a fetish for them. Like, “We’re 15 billion now, let’s get to 20 billion!”’

Would you say the principal metric of success has now become the scale of business?

Tim: Yes. It’s like that Austin Powers ‘100 billion dollars!’ scene. That is now the goal. But a billion dollars? I mean, how big were fashion businesses back then?

Cathy: I remember Tom and Domenico talking about Gucci as a billion-dollar brand, which felt like a big deal at the time. But now it’s like, ‘Who cares, that’s tiny!’ I mean, Tory Burch is over a billion dollars. It is all these guys – and it is mostly guys – who are executives, and it is almost like a fetish for them. Like, ‘We’re 15 billion now, let’s get to 20 billion!’

Tim: I remember a big American Vogue story about Alexander McQueen, back when he ruled, and it said, ‘This year McQueen will break $2 million in sales…’ And Patrick Cox, who at the time was riding his whole Wannabe wave, said to me, ‘Two million dollars?! I’m doing like X many more millions!’ So, even that whole smoke-and-mirrors thing back then seems minuscule by today’s standards.

Cathy: McQueen didn’t even make a profit with the Gucci Group until 2008. That’s not to say they weren’t building up their business and doing the things that they were supposed to be doing, but the profit didn’t come until then. I think the point is, people were preoccupied by creativity, and wonderful and inspiring shows. A billion-dollar business simply wasn’t the benchmark. We are all at shows nowadays, some by very big houses, where we despair that the runway is not as creative as it should be; that it doesn’t suit the legacy of the house.

You were saying before that someone like McQueen was given the time to finetune his skills, to build his world. Do you think the industry still has the patience to allow that to happen today?

Cathy: If you think about Demna getting started at Balenciaga, it took a while to fall into place. At the very beginning, it felt like a rollover of the ideas of Vetements; he was definitely experimenting with the classic Balenciaga shapes, but Vetements did creep into it, plus a bit of Margiela. What was so interesting to me was when in 2021 – an amazing year for him and for the house – he did his first couture show, which really clarified his ideas and his skills. It was like he’d taken the history of Cristóbal Balenciaga and married it with the shapes that he was proposing, which in a kind of historical line followed on from Margiela, no question in my mind. But, crucially, he had now made Balenciaga his. And that really convinced me, and a lot of other people, that you could bring in a big talent and, with enough time and enough support, they could remake a house in a way that you didn’t anticipate.

Tim: Demna had lots of experience prior to Vetements or Balenciaga

Cathy: Tim’s right. He came out of years at Margiela, a number of years at Vuitton. Plus he’s from a different part of the world, former Soviet Union, so his is a perspective that fashion hasn’t seen before. He also has that additional skill that you really need in fashion today, which is knowing how to be an excellent creative director, because you are running an entire team of people. So, when people like that are given the opportunity and enough time, then they can make it happen, which makes me feel very positive about fashion.

Tim: How many people do you think are like that in fashion, but never ever have the spotlight turned on them? How many bands were there in Liverpool who were as experienced as the Beatles? How many Beatles were there when they first started?

Why don’t you answer your own question, Tim?

Tim: Well, I look at someone like Lutz Huelle, who kind of comes from a similar background to Demna, and the same sort of cultural crucible that produced Wolfgang Tillmans. That was a scene. I think Lutz is kind of amazing and unsung. He does what he does with extremely limited resources. He is just one person. I am sure Cathy can think of others who are equally worthy of a gig like Balenciaga. Then I look at someone like Dries who has been doing what he does for decades. I thought the collection he just showed was fantastic. Cathy, you look dubious.

Cathy: No, I liked it. I just didn’t like the setting; I thought it was hard to see the clothes. Going past you as opposed to coming at you. I thought their scale was off. The collection was great though. Like every designer, Dries has had great seasons and a few that have been less interesting. What is so admirable about him is the longevity of his label, and the fact he really knows his clientele; his prices are still pretty good, too, compared to many other houses, and he has a following that he keeps growing.

Longevity in itself is worthy of praise.

Cathy: This is my thing about Sarah Burton at McQueen, and the advantage of someone who’s been at a house for 26 years. It just goes against the whole Dracula routine, with these brands turning over people, finding someone else, getting fresh blood in there. I think that says more about who is managing the company and what they know about running a business.

In the Musée Galliera’s 1997 exhibition, there are videos of shows from that year where you see the audience applauding when a particular look is on the catwalk. And now, of course, there’s no applause because everyone on the front row is filming and broadcasting what they’re seeing to their own digital audiences. Everyone is now an active participant, no one is a simply an observer, because everything is about documenting the spectacle.

Tim: Or everyone is an observer and not a participant.

Cathy: You’re not sitting there pondering what you’ve just seen, because your phone has already digested it and is spitting it out to someone else in your universe. I was at a Marc Jacobs show – Fall 2017, at the Park Avenue Armory – and he asked people to not get their phones out and to just look at the clothes. That’s happened several times, but, you know, Marc is a very good designer, whereas if we went to some of these shows and they asked us to put our phones away, we’d quickly become a pretty restless audience.

Tim: Exactly the same thing happens at gigs and in clubs. The things that used to be participatory have become spectator sports in a way.

Is there any truth in the idea that designers are designing with Instagram in mind?

Tim: Yes! But I’d say that was already happening in a similar way when fashion made the leap to cable TV, and designers started making collections that would look good on television. I had producers who were like, [adopts dismissive tone] ‘Helmut Lang? No, let’s do Betsey Johnson because she does a cartwheel at the end!’ It was all very lights, camera, action. They didn’t want the measured, minimal way that Helmut Lang’s models were walking down the catwalk. They wanted Westwood, Betsey Johnson, and so shows started doing more of that.

Cathy: They were doing that in the seventies, too.

Tim: Yes, Kenzo, Montana, and Mugler.

Cathy: Kennedy Fraser wrote about that in the New Yorker in the late seventies – how models were suddenly hamming it up on the runway, pretending to flirt or dance. It was all part of a shift to shows as performance, with models encouraged to express their personalities. It made Fraser feel, as she put it, like ‘an indulgent nanny on the sidelines of a creative playground’. I do think if you look at a lot of collections, like the last few seasons at Saint Laurent, they are very good at packaging it for a digital audience. I thought last season was just boring and repetitive, with all these long, skinny hooded dresses, but this latest collection [Autumn/Winter 2023-2024] had more variety with the tailoring and the leather jackets, and I liked the way it was staged to evoke the feeling in the old InterContinental Hotel ballroom.

Tim: And the catwalk was the same height.

Cathy: And the carpeting was the same as the YSL couture house. But when you look at the collection, he [Anthony Vaccarello] puts a very simplified look on the runway. It’s three ideas: the suit, the leather jacket, and the drapey simplified evening thing. Maria Grazia [Chiuri] at Dior has also been quite simplified in her approach. There are many reasons for that, but I think one of them is about presenting it for a mass digital audience.

Tim: Watching those Saint Laurent and Dior shows, what I thought was interesting now is that while fashion has always fetishized a time – like, this is the Y2K season, or this is the nineties season, or this is the swinging sixties – it now feels like it is fetishizing a place. When we walked in and I saw the ballroom chandeliers, I thought it was the whole notion of ‘things you missed’, which has always been such a strong element with Marc Jacobs or with Kim Jones, and some of the things that Raf has done, too. It is really about evoking the mood of a moment that you missed, and now you have the resources to recreate it. Fashion has become an amazing way to relive things or to experience things that took place before you were even born.

The self-referential nature of the Saint Laurent set reminded me of that ‘lost season’ film that Balenciaga made a couple of years ago, the one that you starred in Cathy!

Cathy: The concept was a bit different: in 1996-1997, there was a season’s gap at Balenciaga, between Josephus Thimister leaving the house and Ghesquière arriving. There was this one season when there wasn’t a Balenciaga ready-to-wear collection. So, Demna had the idea of creating a collection for that season that never happened.

Tim: It was just a video?

Cathy: Yes, Harmony Korine directed the runway film that they staged to make it feel like it was the nineties. They dressed Diane Pernet and I in nineties clothes and put us in the front row; everyone was furiously smoking backstage in hair and make-up. It was very evocative of the time. When Diane and I went backstage to congratulate Demna, we had to do it in the context of 1997, we had to stay in character so to speak. It was a lot of fun. You had all the regular Balenciaga models, like Eliza [Douglas], but the audience was made up mostly of fashion students dressed nineties style.

I remember watching the video but, tellingly, I cannot remember the collection itself. We see this increasingly, like with the Kim Jones show in front of the pyramids of Giza. These incredible shows which, because of the increasing need to present fashion as a visual anecdote, or as entertainment, sometimes end up eclipsing the clothes themselves.

Tim: It is a time and a place, rather than a collection. I’ve got a question – who do you think has been the most influential designer of the System years? I mean, I think it’s Alexander McQueen.

Cathy: He’s been dead for over ten years!

Tim: I just mean generally, as a sort of aspirational presence. More and more I find it’s all about McQueen. When I do my teaching, he is the one designer – regardless of whether you aspire to the model he established – whose creativity, coherence and commitment inspires people, and to me, that makes him a towering figure. It is funny because I wouldn’t have necessarily thought it ten years ago.

Cathy: I agree with you on all fronts, and the reasons are fascinating. I think people are looking at McQueen in contrast to the way the fashion industry is now. And I also think that Sarah and the McQueen brand have had a lot to do with that, keeping alive that continuity.

Tim: The fact that he died seals him in this perfect chamber that can be analysed from every angle. You can make new perspectives on something, but it’s like the Wallace Collection – what do you call those museums where you cannot add anything to the collection, so it remains completely intact, beginning, middle and end? Even now, when I talk to [Met curator] Andrew Bolton about McQueen, we still find new things in his work and his life to discuss, and that is why I think he will ultimately be one of the most important fashion designers ever.

Cathy: I completely agree.

Tim: There’s this sort of weird genius autodidact about him, almost like Mozart, those people who just ring through the centuries effortlessly, and so he is an inspiration on so many different levels. You don’t even have to like the clothing to still be inspired by the attitude.

Cathy: But to answer your original question more directly, I would say that in the last decade, Demna’s reinvention of the house at Balenciaga is really interesting, and just as important as Ghesquière; maybe even closer to the aesthetic principles of Cristóbal Balenciaga. I’m not taking anything away from Ghesquière – they were 15 very exciting years. When you went into that Couvent des Cordeliers, there was a real sense of anticipation. And the amount of stuff that got copied from those collections, whether it was the silhouette or that batwing sweater that he used to do, everyone was obsessed by that; the neoprene, all the shapes and florals. But what Demna has done there is really interesting.

Tim: Although in the eyes of the world, Balenciaga is as known for sweatshirts and trainers.

Cathy: You could say that is pretty smart given how casual the world is everywhere. You can be a luxury business on several levels – you can have couture and made-to-measure pantsuits on one level, and then sweatshirts and trainers on another. It is a delicate balance to pull off, but I think they have been good at it. Because we are talking about this past decade, I would also say Raf, too, certainly what he did at Dior. I think that is becoming clearer to people now than it was at the time. His collaboration with Miuccia Prada is just unprecedented. I can’t think of any other creative partnership that is like that, that’s proven to be both creatively and financially successful.

Tim: No, there isn’t one.

Cathy: I also think Jonathan Anderson gets interesting in the last four seasons because he made a turn in the collections; he took it away from the Ibiza hippie drapey thing they were doing, and he is making it more about high fashion. It’s more challenging, difficult, obviously pegging it to surrealism in the first two collections. I think he’s used the last two seasons to refine his new approach. The shapes are simpler, the fabric and print development more specific, such as those simple shifts in silk duchess with blurry Richter-inspired prints. It’s relatively rare to see a creative director at a successful brand make such a turn. I think Jonathan knew he had to in order to stay inspired. He and Benjamin did say they were getting sick of what Loewe looked like. And I shared their feeling.

Tim: We’ve not mentioned Gaultier; I feel like he is a bit of an unsung hero.

Cathy: I don’t agree, I think he is a very sung hero. He is a little bit like McQueen, like what you were saying, Tim – people will constantly rediscover Gaultier. I think the appreciation level is still enormous.

Tim: But I do think, considering, when you talk about the anticipation of walking into a Ghesquière show, the anticipation you felt going into the Cirque d’Hiver – maybe it was my age, it was 30 years ago – you had this hyped-up hysteria, and the whole palaver of even getting in. That incredible pre-social-media circus. Maybe it wasn’t the K-pop frenzy, but it was pretty frenzied.

Cathy: You would go to a Gaultier show, not just with a sense of anticipation, but knowing that you were going to be shocked, horrified, thrilled. I always felt like he was attacking whatever assumptions you had or whatever conventions you came from – and people were outraged.

Tim: There would be big crowds outside Gaultier. I remember the busloads of drag queens who would come from Berlin for Vivienne, Gaultier and Martine Sitbon. I did a story on them, and they had a fabulous ringleader. It was like this clown car of drag queens that would arrive and just spill out into the show. And then inside you’ve got Madonna pushing a baby down the catwalk in a pram; it’s funny to think about those events that were not for mass consumption, there being no social media.

So little documentation.

Tim: You know an extraordinary thing, [Helmut Lang PR] Michèle Montagne called up Fashion File asking for help, because Helmut Lang hadn’t filmed their shows. They just had no footage.

Cathy: Oh wow, that is amazing.

Tim: It was all slightly cavalier back then. That whole notion of paying models with clothing, so that after Galliano’s shows, those outfits just wandered off into the night.

Cathy: The other thing about Helmut is that backstage he wouldn’t even talk about the clothes. I kind of miss the days with Margiela when there was no designer, no show notes written in advance. You had to sit on the runway and interpret what you saw – there was no explanation.

‘It was all a bit cavalier back then. That notion of paying models with clothing, so after Galliano’s shows, those outfits just wandered off into the night.’

Just to return to social media, how do you feel its rise has impacted yourselves as fashion critics?

Cathy: Personally, when Twitter started I was still at the New York Times and I found it kind of entertaining to see whether I could summarize a show, or a feeling about a show, in 140 characters. But now I’m off Twitter, and I don’t use Instagram for fashion. So, I try to be more and more oblivious to social media. I really felt last season like I am going to go to fewer shows, or go further afield, to try and get off the treadmill of what the shows have become. As a writer over the last three or four decades, I always feel like I try to change my approach a little bit.

Has what you are looking for in a great fashion show changed?

Cathy: I think with my own maturity and my own understanding of things, I am looking more for things that are truly technically well done, and that are just well thought through. I’m thinking of Jonathan’s last Loewe show. I feel like I am more clued into things like that now. But then, when I think of Demna’s amazing Parliament show [Spring/Summer 2020], which looked like the European Union assembly room, it struck a chord because I’m always looking for designers who can express social or political aspects of their time.

Tim: What in your writing do you think people are responding most to now?

Cathy: I think it goes back to what we said earlier: there is this curiosity for things in the past, so I find I get the most feedback when I have included some historical context, like, ‘this was based on the original Saint Laurent staging at the InterContinental’. There is feedback from readers who need more perspective, they like that. They also like that you are willing to say that something is not as good as it has been, like with Chloé. I don’t think what Gabriella Hearst does at Chloé is interesting compared to the many stages of its past. I think it is important to say those things and I feel that there is feedback to doing that. I get comments because I have done that.

Tim: I feel that I am a contextualist, more than a critic. I rarely say, ‘this is shit’ or ‘this is fabulous’. But I tend to write more about what I am experiencing in the moment – it could be the hair, the make-up, the music or the backdrop. I love all of that, and I find younger people are much more interested in context than older people. They’re much more likely to say – it sounds glib – ‘Oh my god, you actually saw a Claude Montana show in person.’

Cathy: I agree. People tend to get so excited about things, and not to be snarky about it, but it’s also important to say to them, ‘This is how it was done the first time around’ or ‘This thing you’re seeing today actually comes out of this’. I think that contextualizing something is also a way of saying it is not new, so cool your jets a bit.

Tim: Yes, you do see people getting very excited about things that you’ve maybe seen four or five incarnations of. How many times you have been absolutely blown away by a show? I remember the first show I ever saw in Paris was Saint Laurent at the InterContinental, which was amazing. Also, going to a Geoffrey Beene show in New York, and seeing people crying. I want to cry at a fashion show again. Have you ever?

Cathy: I don’t know if I ever cried, but there have been some emotional things. My time covering shows starts in 1986, and I think we’ve seen so many interesting things in our times. I think of Romeo Gigli’s Murano glass collection, just the sound of the glass was like a ridiculous fantasy. Some of the Gaultier shows. I think of Helmut because there was such a sexual undertone in his collections and the way they were presented; the way they were done was so new at the time, and it’s hard to put your finger on, which for me is the essence of fashion. It should be strange and mysterious, and you can’t figure out why. Raf’s History of My World at Parc de la Villette. His Dior show with the flowers on the wall [Autumn/Winter 2012]. The Marc Jacobs Karole Armitage collaboration [Autumn/Winter 2020]. That was a moment in time; I think it still is. And I can think of a few Margiela collections. We could go on; there are plenty of those shows.

In the last decade?

Cathy: I would say Demna’s first couture collection in July 2021. Absolute silence in the room, people walked away just breathless. As I mentioned before, it was the clarification of everything he’d been trying to do up until that point. It was all summarized in that collection and the way it was presented in that historic space. Tim was talking about the fetishizing of the past, I mean, that was like the perfect example. It wasn’t even the original salon, but it was made to look like the original salon.

Tim: For me, and it’s not as grand as that, but when Craig Green did the Children’s Crusade collection, I don’t know what it was called in real life, that’s what I call it, and people were just sobbing. That was a real moment for me.

Cathy: I am generally very optimistic about things, but I do think one of the problems of the last decade is that we don’t have enough forward-thinking designers. We don’t have enough truly experimental designers. For a lot of these companies, especially those with such a legacy and heritage at stake, the designers tend to use the past as opposed to really thinking about the future. The thing that is concerning me is that, with exceptions, the next thing won’t come from designers over 50. It will come from those in their twenties and thirties. That’s true, historically. Look at the influence in the 1990s of McQueen, Margiela and Helmut Lang, to mention a few. But the number of designers who are influential today at the same age is not great. That should be a concern.

Tim: You went to Sunnei in Milan, where there were people crowd-surfing, and saw how it struck a chord with that audience. If you think the new wave comes from people in their twenties or their teens, maybe our wave has already crashed on the beach and we are lying there with the starfish and seaweed, and these waves are coming, and we might be oblivious to them.

Cathy: Maybe, maybe. This might be a little naive, but it makes me think of what Rudi Gernreich said in the late sixties, about how the future is going to be something that is made with technology, and the fashion will have to come from that. We have seen 3D-printing and some moulded garments; again, Demna in this last collection, he did that airbag technology [Autumn/Winter 2023-2024]. But it is still going to have to be something not based on the clothing that we have known for the last 100 years, since women in pants is 1920s onwards, so from there.

Tim: We still only have two arms, two legs, a head and a torso, so until we get to a Cronenbergian style of body modification, which is here and could easily become more prevalent… As we enter the decadence of this civilization, surely there will be more extremes of this. I haven’t seen Crimes of the Future, but everything about that sounds so feasible, that sort of grotesque exhibitionism, the fascination with cruelty.

Cathy: One thing that we are seeing that is fascinating and kind of curiously life affirming – we saw a bit of it on the Oscars red carpet, which is pretty ghastly – is seeing girls wearing a lot less. Miu Miu did the underpants this season, although Miuccia had already done that in the nineties, but now we are seeing more girls wearing less out in public – guys, too, but I am focusing more on women and how they are dressing. You see a lot of semi-nudity on the streets of New York, when it is warm, and you’re also seeing different aspects of male dress becoming really irrelevant, namely the tie and the collar. You are seeing guys wearing different versions of the tuxedo. So, all that is kind of interesting, and then you think: will it get to the next phase where it’s some sort of garment that’s made of recycled plastic and you just put it on?

Tim: That’s another reason why McQueen is the most influential designer of the last 30 years, his whole thing about transhumanism. He did kind of respond to that idea in his work; he was so ahead of the curve in so many things. I mean, it’s slightly beyond me, but it seems to be more and more of a possibility. And you can imagine a fashion response to that will be fairly radical and revolutionary.

Cathy: Transhumanism or some sort of costume… maybe it’s a spray-on thing. Jonathan Anderson did those stick-on sweaters for Fall 2023 – not very sustainable, mind you. They will be sold in a big sheet, and you just peel them off a sheet of paper and stick them on and you are ready to go. They look so real, like a knitted sweater. It’s a funny idea. But then you think, what are the Diors and the Chanels of the world going to do? Because they’re about selling their legacy. It is hard to imagine them doing a moulded suit when they’ve got to keep selling the perfume and the camellias and all that stuff.

If you looked at the three big Parisian fashion houses 20 years ago, you had Galliano at Dior, total maverick; Karl at Chanel, in his own way a maverick persona; and you had Tom Ford at Yves Saint Laurent, who had reinvented the role of the designer as a kind of entrepreneurial-creative-director-sex-symbol. If you look at those same houses now, you have Maria Grazia Chiuri at Dior, Virginie Viard at Chanel, and Anthony Vaccarello at Saint Laurent, all of whom are very successfully serving their respective houses. But could you envisage a true maverick at the helm of one of those big Parisian houses today?

Cathy: I think you could say that Virgil was a maverick, certainly within the world of Vuitton and LVMH. He was really attuned to what was going on in the world at that time, and his skills at communicating were so impressive.

Tim: Virgil talked about Duchamp a lot, and I wonder if when we get around to putting him in perspective, whether he will be regarded as a Duchamp in fashion? He would make those Duchampian objects, like he reconceptualized art exhibitions and cars and all sorts of different things. The way he kind of elevated and made art out of the banal. Then, when that was levelled to him as a criticism, he would just say, ‘So?’ His response was always so measured. He was kind of criticism proof.

‘Virgil talked about Duchamp a lot. I wonder if when we get around to putting him in perspective, whether he’ll be regarded as the Duchamp of fashion?’

He was never defensive about the ideas either.

Tim: No, he was never defensive, and he was never overly absorbed by notions of authorship. Everything that he said resonates more than a lot of what he actually did, even though he did so many things in so many different arenas and was so energetic. But if you wanted to pin one thing to him, like you would, say, the Bar Jacket for Dior, or an incredible wedding dress for Balenciaga, or Ziggy Stardust for David Bowie, there is not really one thing that defines Virgil.

It is probably him, Virgil himself.

Tim: Yes.

Cathy: When it comes to mavericks, I think it’s really a question of how much risk the CEOs of those big houses are willing to take. I think they should take the risk, but are they willing?

Tim: I think it has to happen; it has to. Because there is a slight merry-go-round feel just now to what’s going on.

With Paris becoming so dominant, what effect is that now having on New York, Milan and London?

Tim: London is still what it always was; the sort of scrappiness of it, the sense of the crucible, of people doing fashion because it’s what they want to do. They’re not hell-bent on becoming millionaires, which I think eventually is what crushed New York; you got the sense that those young designers were hell-bent on success. In London, success meant something different for young designers because London never had a Calvin or a Ralph or a Donna Karan. London had Norman Hartnell, and with Vivienne Westwood as a figurehead, there was this fabulous eccentricity that made for really exciting creativity. There have been times when New York was exciting, but I think New York always had different priorities to London or Paris.

There wasn’t the creativity in New York to feed its business in the end, while in London there wasn’t the business to feed the creativity. Milan had a sort of balance but then there was always the Italian-ness of Milan; there wasn’t the eccentricity or the spice. With Paris, you get the business, the creativity, and the spice.

It’s the perfect storm.

Tim: And surprisingly, given the intractability of the French, it’s Paris that had a sort of acceptance or a patience, as we said before, where things have been allowed to develop until there’s a payoff, so you get designers from all over the world who’ve been around in Paris forever and still are, like Dries, Rei, Yohji, Junya or XULY.Bët.

Cathy: I think you’re right. I do feel more confident about London coming back because it’s had such historical up-and-down periods. So we might see a dry period for a decade and then someone will emerge who’ll be really interesting. New York is a bigger issue; it’s shocking how much it has declined. Calvin, Ralph, Donna Karan seems like a golden age, that was the roaring eighties and nineties, and I don’t see anything positive in the future of New York.

Since Raf Simons left Calvin Klein, how do those types of brands gain a renewed fashion interest or look to compete with their Parisian counterparts?

Cathy: They should be able to but that has always been the puzzle of New York, why can’t a luxury brand get going there? Ralph is probably the only one, and I think that’s down to the complete 100% dedication of Ralph Lauren to that idea; that is really what it takes. That’s what drives the Arnaults to be dominant, and it’s what drives the Dumas family at Hermès. But there isn’t that commitment in New York, and I just think business crashes into everything. I think the speed of change in the United States is a big factor, too. People move on, that is our history; it’s all change, change, change. With Ralph Lauren, they have been very smart over the years. Michael Kors, too. For me, it’s not exciting fashion but it is who Michael is; he has come from bankruptcy to build that up, and he has good partners. That’s rare because there is a shortage of partners in the United States. Ralph had great partners; Calvin had Barry Schwartz. Calvin is now a public company and the whole situation with Raf was a great idea, but the moment the numbers started to flutter…

It was over before it even started.

Cathy: It was ambitious of Calvin Klein and its parent company, PVH, to hire Raf. Look at what Calvin Klein had – a runway legacy, the jeans and underwear, a history of provocative advertising and collaborating with great photographers, and good marketing. The elements were all there. And Raf is a thinker, as well as a team builder. But maybe the problem was, ultimately, a difference in expectations about how to accomplish everything. And don’t forget that PVH is a public company – it has to be accountable to shareholders.

It almost felt like it was trying to replicate a European house hiring a designer, but without matching the culture of those companies.

Cathy: All those success stories in Europe are all partly a function of that designer and CEO connection. In New York, we do have some talents coming up. We have a really interesting designer in Elena Velez, who I really like. She is very stripped down, very rough and raw. She is a spiritual child of McQueen’s view of women and femininity, but a very hardcore look at it. I like all that. I like Christopher John Rogers, too. I am trying to think of others… I think Proenza had a great show last season; Marc Jacobs not showing again on a bigger stage, as part of fashion week or wherever in Paris or New York, is a shame; The Row, as you mentioned earlier, the Olsen sisters have moved to Paris…

Why do these labels go to Paris? For validation?

Cathy: They get more attention there. The Los Angeles designers Co skipped New York; they went straight to Paris. It just isn’t a prestigious calendar in New York any more.

Are fewer people coming over for it?

Cathy: Yes, especially Europeans, I don’t think I see any now.

Moving along, how do you think this period of fashion will be considered in the long run, in terms of social history?

Tim: I think this time will be written about as a prelude to whatever comes next. I think whatever comes next is going to be a lot more major.

In what way major?

Tim: Climate change, and so on, World War III maybe, but all of this is a prelude to that. So I think fashion will be written about as just one more business that contributed to the destruction of the world: the giantism of multi-multi-billion-dollar companies, the insane levels of waste. When people are confronted by mountains of clothing in the future, as they already are in parts of Africa and India, these issues become insurmountable. They are currently tucked away in African countries or India or Turkey, but when you see Marine Serre or Priya Ahluwalia’s films of those places where mass-produced clothes go to die, that is how I think fashion will be talked about.

Cathy: I’d agree with that, and I think that the issue of inequality and privilege is striking, too, because the prices of some of the ready-to-wear stuff we are writing about is kind of shocking. And the sheer waste. The amount of leather we are seeing on the runway startled me; in some of these shows there is so much of it. Like I said at the beginning, we are in this whirlpool; maybe people felt something similar in 1830, 1820 – at the end of that era of individual handmade creativity of the 18th century, and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and mass production. If you think of digital technology as we know it, it’s only been around for 15 years. So, we’re in this bridge period where we still value craft tradition in fashion – this is what Vuitton and Hermès are selling – but the reality is, we’re in this other era where the selling and marketing and the image matters more than ever before. People have only just got their teeth around the internet and Instagram and TikTok. In the future, Harvard Business School studies will be done about all that. For the creative part? In terms of design? Not so much.

‘There’s an historical link to how the elite dressed up until the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. It’s the same now, but with luxury products.’

It is ironic that for most of this past decade, the wealthiest individuals in the world have been in technology and communications – less manufacturing – and now they’ve been replaced by a man who is old school, who sells products and makes things.

Tim: You see, I do think there are germs of reaction, because you can’t go on exalting practices that are ultimately abusive. You can’t go on celebrating the ludicrous success of people like Elon Musk without creating a response that will be, I think, quietly virulent and quietly violent. As Cathy says, the world is only getting more inequal. We all read about Shell and BP’s record profits last year because of the war in Ukraine, while at the same time people are unable to heat their homes. I mean, something has to give, surely! What was that movie where rich people floated around in space, while earth was a hellhole?

Cathy: I do think there is a historical link to all this with how the super elite dressed up until the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. I think that we are kind of in that time again, and it is all about these luxury products. I am not sure that anyone can look that far ahead and see what sort of responsibility lies in their hands. Maybe they should. I mean, there are people making some strides in terms of being circular and reusing certain materials, but it is a drop in the ocean in the long run. I think Tim is right, at some point people will react to what fashion represents.

Tim: It’s also worth considering if the designers themselves are actually comfortable with all this. I interviewed [Jil Sander designers] Luke and Lucie Meier yesterday and at one point we were discussing how they are trying to make their business as ‘responsible’ as can be. And I said, well as far as I’m concerned, fashion is this great paradox, it’s a business that is built on consumption so it simply cannot be sustainable. And Luke said, ‘There is the contradiction that’s not easy for us to think about all the time either.’ They looked rueful.

As observers and critics of fashion, do you feel that you should be scrutinising these aspects of the industry as intensely as you do the creativity on the catwalk?

Tim: Yes, especially because it still doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. And the issues are too urgent for that. I love Gabriella Hearst’s passion, but when she talks about how the future will be saved by a fusion of artists and scientists working together, it does beg the question, ‘How soon?’ Because it needs to be now!

Cathy: A lot of it does feel more like marketing. I feel like I do comment on it, and I am really struck by how we have sat through shows with 80 exits, and seen a lot of shows over the last 25 years where it’s just like, ‘What’s the point of this stuff being on a runway?’ I mean, talk about waste.

Tim: I guess I am trying to remain optimistic, but I have no crystal ball to gaze into. I do think that fashion does address something insanely primal; it’s one of the most outward expressions of human desire, which is why it’s a shame it gets so manipulated. Although desire exists to be corrupted, I guess. Fashion will always be there.

Will its focus shift away from the fashion designer?

Tim: I think that during the pandemic people realized that when the world thinks about fashion, it thinks about a creative individual. Whether it is an illusion or not, it is based on an individual doing something, making something, imagining something desirable that other people will want, whether that’s bags, shoes or dresses. If you ask people what fashion is, I think most people would still say it is about designers, rather than gigantic multi-billion-dollar corporations sticking a shop on every street corner in the world.

I’m not so sure.

Tim: Really?

On a mainstream level, I find fashion represents an entry point to a kind of generic luxury lifestyle that people associate with the Ritz, private jets, strutting with attitude for TikTok, wearing your look. I think the lifestyle aspiration is, for many people, more alluring than the actual design of, say, a Saint Laurent dress or a Vuitton bag.

Tim: Like the Kardashian-ization of fashion. I think the theme of this conversation is that the whole idea of what fashion’s initial impulses were has gotten bigger – the illusion got bigger, the aspiration got bigger. Now, the aspiration isn’t simply to have that little dress or that little designer bag, it’s to have the private jet to walk onto holding the bag or wearing the dress.

I’m interested to get your thoughts on the Kardashian and Jenner phenomenon. Ten years ago, they were on the slightly unfashionable sidelines of the fashion industry. But over the past decade they’ve become such a potent catalyst for fashion’s links to the wider consumer world.

Cathy: I remember when the Kardashians and the Jenners were seated at the Balmain shows and everybody was going, ‘What the hell?’ Which is weird in a way, why the Kardashians and the Jenners have raised such a concern in fashion. Like, ‘Oh my god, it’s reality TV!’ which was seen as weird, and yet they were the beginning of that wave of all types of celebrities coming in. Musical artists and reality stars. The more extreme physically, the more outrageous, it was all OK. Now it feels like the Jenners and the Kardashians are…

…the establishment?

Cathy: Well, they are the benchmark. They’re at Balenciaga; they’re at Versace. They’re modelling for all these different brands; Kim has her own shapewear business. They are all doing something, and I don’t think the interest in them has waned. I just think we’ve all become quite blasé about it, because we’re so used to seeing all these people on the front row.

What about you, Tim?

Tim: What do I feel about the Kardashians? Well, they were born from a sex tape and a reality show, so in that respect they are consummate emblems of the times. Did they find fashion or did fashion find them? Who was the significant figure in the whole thing? Is it the mother? She certainly managed to transform four or five quite ordinary people into these paragons of aspirational fantasia. Fashion didn’t transform the Kardashians, the Kardashians transformed fashion, and when you see all those women in the street with their puffed-up lips and puffed-up butts, you understand that is all about the Kardashians making a style. I wonder how much of a part cynicism played in all this? You know, is Kris Jenner the supreme ironist of pop culture? Is she the Warhol who’s made them all superstars?

‘What do I feel about the Kardashians? They were born from a sex tape and a reality show, so in that respect they’re consummate emblems of the times.’

Which aspects of this do you see as interesting?

Tim: I hate to say it, but it kind of passed me by. What is fascinating about it is the way it is so utterly transparent and yet seems so convincing to people. Like a play and a ploy. When you look at something that isn’t in your ethos or your aesthetic in any way, and yet it seems to be so seductive to so many millions of people, then you do think, ‘Oh, this is why I feel really out of place in the human race!’ Don’t get me wrong, I would never judge people for loving the Kardashians, but I was completely mystified. But then again, I never got reality TV either, I never got The Osbournes, Big Brother, all those things. I just thought no, it is all around us, we don’t need to see it on television every minute. That’s why I was fascinated, because I just didn’t get it. But when I did talk to Kim Kardashian, she was really lovely, and was kind of funny. Like, it’s a joke that she is in on. Well, you would hope that, and I guess maybe she is. And I certainly think that she is still capable of surprising us in some way.

They definitely have their part to play in what people now refer to as the ‘attention economy’. Certainly, attention is the goal – in fashion, like everywhere else – and yet it seems to be a fine line between good and bad attention. Fashion has seen its fair share of car crashes over the past decade, but how is this affecting fashion in general, and the role of the designer as a public figure? Miuccia Prada said she no longer feels particularly comfortable doing interviews for fear of being misquoted. But when designers are fearful of speaking, doesn’t it become damaging to the whole ecosystem of fashion?

Cathy: That’s a good point. It is a challenge that journalists are increasingly going to face, getting access to designers to really talk about what they do, otherwise it’ll become a very manufactured process. It can already seem very canned at times, which is troubling. When I think about my backstage interviews with Lagerfeld, I just think how incredibly generous he was with his time. By inviting you into the Chanel studio before the show, you got to understand, what his references were. He recognized the value in doing that.

Tim: I would say that designers are much more attuned to interviews and that whole self-promotion process than they ever were before. In days of yore, designers like Ungaro or Saint Laurent were terrible interviewees because they simply weren’t used to it. There was no precedent for being available to the press all the time, even in a controlled way. Now everybody appreciates that’s part of the game; they need to have a schtick. But I don’t think that is just fashion, it’s everything. Every contestant on every reality show knows they need a backstory.

Cathy: There are some designers who do still give you time, who are generous with their reflections on fashion or broader topics. But as a consequence of the brands becoming bigger and bigger, the designers are becoming increasingly remote from that process, and more distant from the people in the media who can actually talk and write about fashion intelligently. Perhaps the shift is more towards the influencers.

Influencers are good for business. Journalists aren’t always good for business, even though they may stimulate progress or elicit some kind of self-reflection.

Cathy: I don’t believe that. I think most designers continue to think the journalists and the critics are necessary. I certainly hear that more than I have ever heard it in the past – from the designers and the people around them. They know there are a shrinking number of good journalists and good critics, who have a longevity, a history in the business, and who can talk to them about their past in fashion. That is not to say there won’t be new writers and critics coming in; thankfully there are. I think the good designers still value that, but some of them are closing shop.

Tim: What is happening in fashion is happening everywhere: if people would rather not talk, that’s not just fashion designers. As I mentioned earlier, I think that with the supermodel moment 30 years ago, fashion became a branch of the entertainment industry. And that was when PRs began to realize that their clients needed to be doing not just press interviews but mainstream media interviews – to be part of the new world. So you’d see designers getting lured backstage after a show and being forced to say something when they were exhausted and fraught. I remember getting Claude Montana pushed in front of my microphone quivering like a newborn lamb. Over the years, people wised up to that and learned how to do it, and then you’d have Tom Ford demanding ‘Three questions only!’ That became the policy everybody seemed to be adopting, which was kind of ridiculous because there were people you wouldn’t even want to ask three questions to!

‘Designers were now forced to talk to us backstage. I remember getting Claude Montana pushed in front of my microphone quivering like a newborn lamb.’

All that now seems rather innocent compared to today’s era, where the constant gaze of social media can feel like CCTV.

Cathy: That’s new media. If you think of Olivier Rousteing as an early adoptee of social media and Instagram, he was really on it when it comes to how to engage with the customers and the wider world. If you talk to Olivier now, I find that he is a little burned out by the whole thing and has been terrorized by it.

Tim: With social media there is a different weight to the words. And from there you have cancel culture, and everyone wondering what they can or can’t say. So now there is an additional layer in the communications, which is like a minefield that everyone is negotiating.

Is that here to stay?

Tim: I think that it’s an evolutionary thing because we don’t really know where social media is going to end up. Do we go to a time of complete honesty? Does that become the best way forward, where everyone is honest and says what they think, and everyone is given an opportunity to explain what they meant when they say something that jars with an audience? Which doesn’t exist at the moment. You are just tried and sentenced in a heartbeat and there is no recourse. Will there come a time when people might accept that this was a really strange, extremely insecure, unhappy moment, where aggression and victimhood were kind of your only two options? I don’t know.

‘Is all this brand power built on old Parisian heritage names actually to the detriment of fashion – because it doesn’t feed enough innovation?’

Finally, what can you say about the next decade in Paris fashion? Or rather, what could an LVMH or a Dior look like in ten years’ time?

Cathy: Assuming LVMH and Kering are managed properly, those companies will just get bigger and bigger because that is their pattern. Their shareholders and the owners expect growth. So, I think that continues, and so we’ll see fashion houses entering an ever-larger phase. They might get more involved in film – in the way Saint Laurent have announced they’re going into production – or in having even bigger shows, or events at the Stade de France. I remember Lagerfeld saying to me years ago, in the early 2000s, that Chanel’s annual show budget – two couture, two ready-to-wear and one métiers d’art – was something like €20 million. That seemed an astonishing amount – then. And it was, considering the kind of sets that Chanel built in the Grand Palais. And now we have resort collections staged in places like Seoul and Rio. And also shows that require enormous sound stages to create make-believe worlds. Think of some of Demna’s spectacular shows for Balenciaga.

Tim: Those resort shows alone must cost ridiculous sums of money.

Cathy: But I do sometimes wonder, is all of that brand power that’s built on old heritage names actually to the detriment of fashion, because it doesn’t feed enough innovation? I guess someone could come into Chanel and take all those delicious references and make something new out of it and we will sit there and go, ‘That is amazing.’ I think that is the beauty of some of these houses like Chanel, Saint Laurent and Balenciaga. Again, I praise Demna for what he has done for Balenciaga, who knew that could happen? Somebody could do that with Gaultier. Should do that with Gaultier. It is ripe for the picking, and we need that. But I just hope that there is one new voice that emerges, a new aesthetic in the next ten years. Just one person – I only need one.

It’s gone from Lagerfeld’s three designers in a decade to just one.

Cathy: I am OK with one.

So, for you that one person this past decade would be Demna, right?

Cathy: Yes, I’d say it’s been Demna. And I think the example of Mrs Prada and Raf has been really instructive, and it would be nice to see that at other companies. Giorgio Armani, are you listening? They should bring in someone, with the open acknowledgement that they will be taking over when the founder is ready to retire. But when it comes to the individual rising out of nowhere, hungry talent, I think one will do. I am doubtful – the odds are so against it happening because of the size and the amount of real estate that the big groups all control. I think that the excessiveness with the brands, the way that mass culture works, the way that globalization works, all these things are in their favour, and they don’t really help the young designers coming out of nowhere. But I do think that across all fields there is always a counter reaction – whether it is an art or food movement, organic or climate change – that reverse situation when people start embracing smaller entities. So, it is possible. Obviously a lot of talent is out there, but it is figuring out how to exist on a smaller scale. The people who cover fashion and the people who go to Paris, we are all used to those big daring talents who get on that stage. That is still the benchmark.

Tim: How I see it, the question about the future is bigger than the answer that fashion could provide. Going back to what we were talking about before, it is interesting how there is so little ethical leadership coming from the people who are allegedly in charge of our lives. Wouldn’t it be amazing if it was fashion that could offer some kind of leadership? It seems like a bizarre enough idea that it could actually work. Like, fashion suddenly thinks, ‘Hang on, we’ve got all this money; we employ all these people; we are an economic force in the world, and we have had an incredibly negative impact – let’s see if we can turn that around.’ And maybe… although it seems inconceivable within the next decade.

You could also ask the question, ‘Does one person really need to own €200 billion worth of assets when €10 billion is perfectly reasonable?’