Costume designer Heidi Bivens on the fashion which inspires television which inspires fashion.

Interview by Rana Toofanian

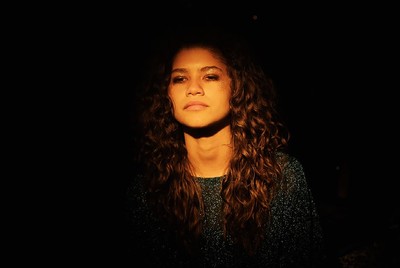

Portrait by Blossom Berkofsky

Costume designer Heidi Bivens on the fashion which inspires television which inspires fashion.

Few TV shows have inspired runway collections like Euphoria has. The aesthetic, mood and styling of HBO’s hit series, which follows a group of Californian teens as they navigate love, relationships, sex, addiction, and identity, can be seen in everything from Miu Miu’s low-cut pleated skirts and shrunken cardigans to Coperni’s high-school inspired ensembles. Indeed, the show’s ability to revitalize luxury labels, raise up independent brands, and even revive entire categories of clothing is a phenomenon that’s been described as the ‘Euphoria effect’.

Much of the show’s impact on pop culture can be attributed to costume designer and stylist Heidi Bivens. Just four years and two seasons in, Bivens has created a mark on the cultural zeitgeist so distinct it merits the creation of a 272-page book, titled Euphoria Fashion, in its honour. Published by the show’s producers A24, the book serves as a comprehensive encyclopedia of annotated archival images, offering readers a feast of mesmerising visuals and intimate conversations with cast members Zendaya, Sydney Sweeney, and Hunter Schafer, among others. The foreword is written by Jeremy Scott, who describes Bivens’ ability to bring complicated characters to life through their clothes as ‘a skill very few people have’.

Becoming a celebrated stylist and Hollywood costume designer wasn’t always on the cards for Bivens. Born in Annandale, Virginia, she moved to New York to study film and journalism with the hope of landing a job on a movie set. After all, styling ‘wasn’t a career path many people were familiar with,’ she recalls. But after interning at Women’s Wear Daily and W Magazine, she landed a job as a wardrobe assistant on Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Bivens now balances her work on hit TV shows with styling for Chanel – collaborating on several campaigns with Inez and Vinoodh for the house. Bivens sat down with System to talk about transcending the boundaries between fashion and film, and how the entertainment industry’s ever-evolving love affair with clothing has been consolidated.

What were your earliest memories of fashion?

Annandale, Virginia is more built up today than it was when I was growing up there; it was a suburb back then. I moved to New York when I was 18. I grew up with an older sister who was very into cinema, especially more obscure and arthouse films, and who had film posters all over her bedroom walls. She turned me on to David Lynch and other filmmakers like Gus Van Sant and Jim Jarmusch. It was through my love of film that I knew I wanted to come to New York and try to get a job working on a movie set. I just didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do. So, I applied and got into Hunter, which is part of the City University of New York and at the time had a reputable film programme. I used to brag that Woody Allen went there; I don’t brag so much any more. So, I moved to New York and lived in college dorms. I studied journalism and filmmaking because I was interested in writing in general, writing narratives and stories. In particular, I was interested in investigative stories. That’s why I liked the idea of working for a magazine, so I started looking for internships.

When I finally got a job working at a magazine, I knew there was a job with the title ‘fashion editor’. Ever since I can remember, my mum collected Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue. I would look at her magazines, and I was very aware that someone had to pick out the clothes for these shoots. But it wasn’t until I began working for a magazine, trying to get my first bylines as an intern, that I started to understand what styling was. I then got a job as a market editor for Paper Magazine very early in my career. And that led to me doing shoots when I was 19 or 20 years old.

How would you describe your experience working as a stylist and market editor in New York at that time?

I interned at Women’s Wear Daily and W when Fairchild Publications was on 34th Street near the Empire State Building. It was very exciting to work in this huge newsroom. Everyone worked in one room except for the editor-in-chief and the publisher, whose windowed offices were along the walls. The fashion editors at the time I really looked up to were Joe McKenna and Alex White. I would see them putting their books together, working on their portfolios, laying all their tear sheets out on the desks and on the floor. Alex White did that ‘Cowboy Kate’ homage story for W with Craig McDean [in 1995], and I was stunned by how beautiful the images were. It was a great era for W. [Creative director] Dennis Freedman was there making amazing work, too. I was at these magazines because I thought I wanted to be a writer. Then I discovered fashion styling, which at the time wasn’t a career path many people were familiar with. I quickly realized I could make a very decent living as a stylist, and that it could also be a segue to get onto film sets by drawing on my skills and applying them to costume design. The first job I ever got on a movie was as a wardrobe PA on Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. I remember talking to the film’s costume designer, Melissa Toth, about what value I could bring to the project when I was vying for the job. I told her I could approach prepping the movie like an editorial. I could call brands; I could ask to borrow samples; I could help build the characters’ closets through the same methods I would use when styling fashion editorials. At the time, that wasn’t something costume designers were doing, and there wasn’t much crossover between fashion and entertainment in terms of styling. Arianne Phillips was one of the only people who was doing both. It was uncharted territory to blend the two. So, instinctively, I felt I had a bit of an edge.

I wanted to create style tribes within the [Euphoria] school. I always loved how i-D would shoot groups hanging out in a London park or outside a club.

Was there anyone you looked to as a mentor?

Arianne Phillips was definitely a chosen mentor of mine. I was inspired by her and how she was setting new precedents. By the time I met her, she had probably already heard me talking about how I was inspired by her, so to me, it felt like we had already known each other. I think for her it was a fast connection to me because I had so much respect for what she does. Lou Eyrich is another chosen mentor of mine. She works with Ryan Murphy, and designs costumes, and produces and oversees all of his shows. She has also set new precedents. I’m constantly attracted to women who are breaking ceilings; women who have a vision that either a studio or a producer or a magazine says no to because ‘we’ve never done that before’, but who then find their people to help them break through and set a new precedent. That’s so exciting to me on a lot of levels. It’s sort of a metaphor for how I want to live my life in general.

What makes a particular work or aesthetic important to you?

Sometimes people ask me about my favourite films or costume designers. It’s such a difficult question to answer because my love of film and TV is about storytelling, not so much aesthetics. It’s about the emotion and the feeling, and costumes can bring both. I often remember films and stories because of the memory and emotions they evoke. But then there are films like Blade Runner, which make you feel a certain way because of the way they look. Then there are films that are incredibly beautiful and have a singular vision behind the production design and the costumes, but they’re really bad movies.

As a costume designer, how do you balance the visual appeal of a costume with practical consideration? For instance, does the costume work for the actor? Are they comfortable? And then, of course: is the costume authentic, and is it believable within the context of the film?

There are definitely different approaches depending on the genre, the director’s vision, and all the details that go into what type of film or TV show it’s supposed to be. For me, I want to be involved with stories that involve world-building, even if it’s contemporary. I really love the fantasy aspect of being able to create a reality within a world that doesn’t necessarily reflect stark realism. I’ve done pedestrian costumes that are supposed to be really real. For example, when you’re working on films that are either biopics or historical, it is important to stay as true to the history as the director’s vision allows. But I love it when a costume designer has had the opportunity to do a historically accurate costume, but they do their own take on it. I enjoy those types of films more than ones that are historically accurate.

How did Euphoria come about?

I had never done television work before Euphoria came up. I’d mostly worked on smaller independent films, not even big studio films. But I was continuously searching for jobs, costume designing, because I wanted to get more experience of being on set and seeing how things really work. It’s been my school. Actually, in a couple of weeks, I’m flying to London to shadow my friend Peter Glanz, who’s directing a film called Polite Society with Richard E. Grant and Claire Foy. I’m very academic about my approach. Even on Eternal Sunshine, I walked into the office, and I really took note of how the costume designer set up her office.

And so, with Euphoria, how did the opportunity come about? You said you’d never done any TV, so what drew you to work on it?

Euphoria creator Sam Levinson had asked me to work on his first feature, Assassination Nation, but I had already done Harmony Korine’s Spring Breakers and so I felt that it was a bit redundant because I’m always trying to challenge myself. In Hollywood, especially in entertainment, you can easily become pigeonholed if you do too much of the same thing. But then, when it was time for Euphoria, I liked the script a lot, but I didn’t know if it was something that I should agree to because I had never done TV before. TV is a big time commitment, and I would have to move to LA for the show. So, I asked some younger friends who were out of high school but closer in age to the characters in the pilot script – and who eventually became part of the show, and these friends were like, you should do this. They felt very strongly about it. This was pre-Zendaya or Drake signing on.

Then the cast just rounded out really nicely – I already knew Barbie [Ferreira] and Alexa [Demie] – and so I felt really good about it. The pilot required minimal commitment before it was greenlit. I was only in LA for five or six weeks to do the pilot, and I didn’t have to sign on to do the show. A lot of people just do pilots and then they don’t end up doing the show because of other commitments. But after I saw the pilot, I was really floored. I get quite emotional thinking about it. I was just really impressed by the cast and the storytelling, and it made me feel like I was part of something different and something that people hadn’t seen on television before.

I used an incredible amount of vintage items, so that people weren’t like, ‘Oh, I saw that on the runway today, or in Saks Fifth Avenue last week.’

How would you describe your vision for the costumes in Euphoria?

From the beginning, I wanted to create style tribes within the school. I always loved how i-D Magazine would photograph style tribes on the streets of London, as well as groups hanging out outside a club or in a park. I wanted to create pockets of that within the school. I pitched to the producers that we would have recurring background [characters], so that we could create these little cliques within the school. That is where my idea for all the main characters’ looks came from, each one comes out of their own individual style tribes. I knew I wanted each of the main cast to represent their own clique.

How did you approach developing each individual character’s unique look, while maintaining a coherent overall visual aesthetic?

I talk a lot about what I call style rules, which is a filter that I run everything through. It’s kind of like how you shop for yourself: if you know what you like and you have a personal style – and not everyone does – you could walk into a store and go through racks of clothes, say: yes, no, yes, no, yes, no. It’s a similar process for me with the characters, but I have to get in the mind frame of the character. It’s not like I’m a method costume designer where I’m inhabiting the character’s emotions. But I have a list of style rules of, for example, the colours they like, including the colours they will and won’t wear. Fezco wears crewnecks, he doesn’t wear V-necks. Jacob Elordi’s Nate doesn’t wear skinny jeans. So, there are these rules that then evolve with the storytelling. Jules, for instance, when we meet her in episode one of season one, is very femme and trying to be girly and even cutesy. By season two, she’s really turned off by the idea of being overly sexualized as a teenage girl. The experiences of the characters are going to affect their decisions each morning when they put on their clothes. That’s how we all live our lives, right?

Euphoria has obviously attracted a lot of young viewers who are influenced by the show’s fashion. What were your considerations for the audience, and especially young viewers, when working on the respective looks?

I’m always thinking of the audience. I’m always putting myself in their place. That’s so important for me – and for any costume designer – because you’re trying to communicate the story however you can. In season one, my main concern was not pulling anyone out of the show by using recognizable fashion. I used an incredible amount of vintage items, so that people weren’t like, ‘Oh, I saw that on the runway today’, or, ‘I saw that at Saks Fifth Avenue last week.’ I really felt it was important not to use big brands unless it was the guys wearing Supreme or some Hypebeast thing. By the second season, I understood that I had a real opportunity to harness the audience’s attention, and that I could excite them with the costumes, while still trying to stump them with vintage. I really enjoy creating a costume for a character that incorporates vintage clothing that maybe people can’t figure out what it is – and then, it’s amazing how they are able to figure it out. One of the ways I was able to do that is with the help of costume houses in LA, these gigantic warehouses full of vintage clothing organized by decade. They are rental houses only available to people in the film and TV industry. That was a huge resource for me, more so in season one than season two. For the second season, I leaned into current fashions more.

The first place actors come to is the costume fitting. So, they’re getting to know the character through our collaboration. It’s a very intimate relationship.

Euphoria has also affected how people dress and how stylists work in so many ways. What would you say has been the cultural impact of the show?

It’s really hard to take any credit for that because there’s no way of proving it. I’m a real hard facts kind of girl. In my opinion, it would be very presumptuous of me to take credit for anything. What I will say is that I’ve come to understand that the images from the show have been on a lot of mood boards. And that makes me believe it has become some sort of reference for people in creative ways. I often talk about this thing called the ‘creative ether’. And the ‘creative ether’, to me, is the reason why you’ll go to shows one season and a number of designers will all be using zipper ruffle details. Or, more broadly speaking, why details come up in different collections. It’s also why editors will do trend reports and, some of it could be like ideas leaking, sure, but some of it is coincidence. It lives in this unconscious ether space.

Also, more people are consuming the same information on social media.

That’s exactly right.

So, you are looking at culture and subcultures on the internet…

I just had an opportunity to put it on television. Not only did I have an opportunity to put it on television, I had an opportunity to put it on a hit show. You could call that luck of the draw. But I also think it has a lot to do with the cast, the creative departments, and Sam’s writing. As well as HBO’s support of the show.

I’m curious about the dynamics of teamwork in terms of working with fashion photographers, designers, and models as opposed to working with directors, actors, and a film crew. What are some of the differences you’ve experienced?

The beautiful thing that comes with age is understanding more about how to navigate different personalities. I love collaborating, and so much of collaborating is understanding people. It’s what gives me joy in my work. If I was left to my own devices, I wouldn’t have as much fun. I’m not interested in a solitary effort. I’ve also come to understand my worth more and more, and that’s really helped me navigate how to collaborate with different types of creatives, like a director. I come from the school of thought that what the director says goes. In order to create successful costumes for a film or television show, it’s important to have a good director and for them to either have a singular vision or let you do your thing. Sometimes it can be both. When it’s both, that’s when the magic happens. That’s what happens with Sam on Euphoria. He has a vision I’m just able to plug into. And I have a sixth sense when it comes to communicating ideas and collaborating. I joke about it a lot because I often know what someone’s going to say; if they’re going to like it or not before they open up about it.

So, with a film director, it’s really about following their vision. Whereas, when I’m working with a photographer and it’s a fashion editorial, it’s more of a collaboration where the fashion editor or stylist brings ideas that you come together on. Film and television aren’t like that – it’s more the director at the helm, while the costume designer is providing a service. It’s rare that you find directors who you can have a real collaboration with, in the same way you could with a photographer. So, when you do find those collaborators, you have to hold on to them because they don’t come along every day. It has to be a meeting of minds. It can’t just be a ‘for hire’ thing if you want to make the real magic happen.

There are films that are incredibly beautiful and have a singular vision behind the production design and the costumes, but they’re still really bad movies.

And is there a skill that you’ve gained from navigating one industry, which has proven invaluable when working in another?

How to work with talent. The first place the actors come is the costume fitting. So, they’re building their ideas for their character and getting to know the character in the fittings through their collaboration with the costume designer. It’s a very intimate relationship. With styling on fashion shoots, it’s often a one-day shoot or a week-long shoot at most. It’s usually not a long-term commitment. But you are still building relationships because you will shoot with the same people over and over again. And when you’re working as a stylist with celebrity talent, for example, you want to build trusting and intimate relationships. It’s important that the talent feels safe and confident having you dress them. By dressing them, you also help them figure out what works for the shot or the scene and help them to tell a story. That’s the similarity between the two career paths: the relationship with the subject, the canvas, the talent, the model.

These things are so collaborative – both fashion editorials and working on a film. How do you feel personally represented in the work you produce and the ideas you cultivate?

I always hoped that there would be a thread running through all the work; I remember saying that at a pretty young age. I have two real hopes. That there would be something consistent in the work so that people would know I had worked on it just by watching it. The second is that I would be respected by my peers; that I would have a dialogue with my peers, as well as their appreciation. I feel that I have accomplished the second. The first thing is so subjective; it’s hard for me to say if I’ve done that.

In fashion, there are strict rules about how looks are visualized in editorials – like certain designers that can’t be combined or runway looks that have to be included. Are there rules when you work with fashion brands on film and television?

Lending for film and TV is still a relatively new territory for brands. When everyone was home during the pandemic, watching more TV and more films, we as a culture began to understand the power that film and TV could have on audiences. With that said, it’s still relatively new. So, rules? Not so much, but that definitely applies in fashion. It comes in waves, but what I’m really happy to see have changed are the rules about gender. For a very long time you would borrow from top runway designers, and they would have a policy that menswear could only be shot on men and that womenswear could only be photographed on women. I always thought that was really shortsighted, but I never hear that rule thrown out at me any more.

You’ve recently been working on several Chanel campaigns with Inez and Vinoodh. How was that experience?

Collaborating with Inez and Vinoodh, and working with Virginie Viard and Marion Destenay Falempin [Fashion Image Director at Chanel] has been a major highlight for me. Over the past few years I took an intentional detour into film and television, exploring storytelling through costume: Most recently,

when fashion styling for editorial or advertising, I’ve been reminded how having a foot in both industries keeps me curious; researching new and established designers inspires me to keep creating interesting characters.

What motivates you to keep going and doing this job?

I have so many interests; way too many things I want to do than I have time for. These many interests take my time and keep me from the one thing that I truly want to do, which is write and direct my own films. I’m hoping to focus more on that now. I’ve started producing, which has been really exciting because it means I can be involved from the beginning, and not just focus on the minutiae of the costumes. It allows me to look at the big picture.

Would you say you’re optimistic about the future and about future projects?

It’s not announced in the trades yet – so I can’t reveal the name or subject matter – but I’m developing a true-crime podcast into a series, with producing partners Bronwyn Cosgrave and Alessandro Del Vigna. I’m also a producer on a feature film that Mary Harron will direct next year called The Highway Eats People, and cinematographer Chris Blauvelt’s directorial debut Disco’s Out, Murder’s In! The next film I’ll costume design is Panos Cosmatos’ Flesh of the Gods with Oscar Isaac and Kristen Stewart. And I’m hoping to have an opportunity to work as a costume producer, overseeing all things costume-related and ushering new design talent into the industry for all television shows I’m attached to.

Photograph taken in artists Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe’s installation entitled Room 7 – The Random Forest, as part of the Colony Sound exhibition, Marlborough Gallery, London.

© Maude Apatow, Marcell Rév, Eddy Chen/HBO.