The meteoric rise of K-pop in luxury fashion.

By YJ Lee

The meteoric rise of K-pop in luxury fashion.

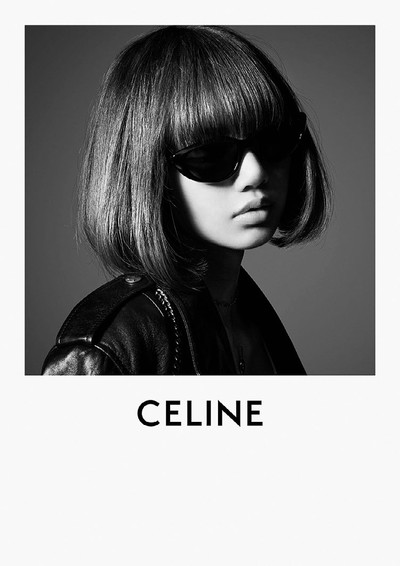

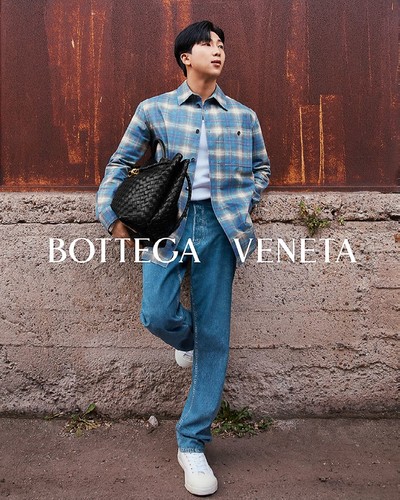

In 2023 alone, more than 30 K-pop idols were named new global ambassadors for luxury brands. RIIZE, a rookie male group hailing from SM Entertainment, signed with Louis Vuitton a mere 98 days after the release of their debut song, becoming the fastest idols to be appointed fashion ambassadors as of December 2023. Indeed, Louis Vuitton reportedly formed a dedicated taskforce in its Paris headquarters aimed exclusively at signing and liaising with K-pop ambassadors, and closed five more ambassador deals with Korean musicians last year, which accounted for nearly half of the brand’s new global ambassador contracts.

While Dior only appointed three new global ambassadors in 2023, all of them were K-pop stars: Jimin of BTS, Haerin of NewJeans, and the brand’s first signing of a whole group as an ambassador, TXT. Since appointing BLACKPINK’s Jisoo as an ambassador in 2021, Dior’s sales in Korea almost doubled from $253 million in 2020 to $473 million, and the house’s overall sales from Gen MZs quadrupled.

For brands, snatching up Korean pop stars is not only a means to stay relevant in Korea – which has become one of the most important markets with the highest luxury goods spending per capita in the world – but also a bet on K-pop’s growing dominance everywhere. K-pop album sales and major agency revenues have both tripled since the pandemic, and the industry is projected to be worth $20 billion by 2031; an unprecedented growth rate for its size. In the United States, the world’s largest market for digital music and streaming, Korean-language songs were the third-most played after English and Spanish-based music in the first half of 2023. According to Lefty, half of the top 10 fashion influencers during this same period were Korean idols – all four members of BLACKPINK and V of BTS – measured by Instagram engagement rate and Earned Media Value. Others on the list were the Kardashian-Jenners, David Beckham, and Zendaya.

Although K-pop’s explosive surge in popularity may seem recent and sudden, its potential has been brewing for over three decades. The first official K-idol group, Seo Taiji and Boys, debuted in 1992, at a time when Koreans were vehemently searching for freedom of self expression. The country had just overthrown a military dictatorship in 1987 and was beginning to form a fresh liberal democracy; recovering from decades of strict government control on education and media. Seo Taiji and Boys emerged from the aftermath of extreme sociopolitical turbulence, and appeared in front of a generation ripe for change. They swept the country with their fusion of hip-hop and electronica, and for the first time, Korea saw the emergence of a ‘fandustry’, where people lined up to buy idol merchandise and assembled competing fandoms. ‘They became a religion for all the kids,’ says Gee Eun, leading K-pop stylist and visual director of Seoul-based record company, The Black Label. As the government continued to lift censorship regulations on imported media and major broadcasting throughout the ’90s, opportunists jumped in and established entertainment companies in order to produce more idol groups. It was during this time that the ‘Big 3’ K-pop labels – SM, JYP, and YG – were founded. ‘There was this shift in culture. It was like everything else that came afterward was acceptable because these groups opened a new door,’ Gee Eun says.

Then, in 1997, the Asian financial crisis put many Koreans out of business and in dire debt. The government sought to bolster the economy by investing heavily in cultural exports, and poured hundreds of millions into creating jobs in locally made music, film, fashion and art. For Korea, popular culture was as important a product category as the country’s automotive and IT industries. The recession had ironically catapulted both its production and consumption power, leading to the first Korean Wave – or Hallyu – throughout Asia in the early 2000s. For the next decade, as demand for Korean music and dramas continued to rise all over Asia – namely China and Japan – K-pop made relatively incremental progress Stateside and in Europe. And the first time K-pop formed a relationship with European luxury fashion on a meaningful level was in 2016, when Chanel offered an exclusive ambassador contract to G-Dragon, the leader of YG’s breakout male group, BigBang. ‘I wondered if such a thing was possible, but at the same time, it was expected,’ says KB Lee, a creative director who connects various brands and artists to Korea, and a personal friend and consultant of G-Dragon. ‘He was the most influential artist in Asia at the time and I was really curious how a fashion house like Chanel would accept him. The relationship between K-pop and luxury fashion houses completely changed after that.’

Mirim Lee, former fashion director of Harper’s Bazaar Korea and co-founder of TMN Agency with KB, remembers the first time G-Dragon and Gee Eun – then the visual director at YG – attended Paris Fashion Week together. ‘G-Dragon and Chanel had this process of getting to know each other. They were both very open to experiencing new things,’ she recalls. In the following interview, Gee Eun, KB, and Mirim sat down with System to trace the origins and meteoric success of K-pop culture, and discuss the ever-evolving impact and influence of K-ambassadors on Europe’s biggest luxury fashion brands.

‘When you try to analyze K-pop from the outside, it can feel like it was a sudden success, but it’s a business that’s had great potential for decades.’

You were young students in the late ’80s and early ’90s, when K-pop started burgeoning. What do you remember about this time?

KB Lee: When I was young I liked music before fashion and I was really influenced by groups like Deux [duo from the early 1990s]. I would go to Itaewon [neighbourhood in Seoul] to find the shoes they used to wear.

Mirim Lee: I really liked Seo Taiji and Boys. I remember their beanie with the big ‘S’ logo was really popular.

Gee Eun: I was still in high school in the beginning of K-pop’s heyday. We always had celebrities before that but with groups such as Seo Taiji and Boys and Deux, that’s when we started getting fan merchandise and we used to decorate everything with their photos. We would stand in line to try and buy Seo Taiji’s accessories or Deux’s advertisement catalogues. Then with the next generation of groups, H.O.T. and Sechs Kies, we started getting this idea of separate, competing fanbases. There was this shift in culture from just buying tapes to participating in fashion codes and I was a kid that grew up in that. I remember Seo Taiji wore this giant acrylic peace sign as a necklace and they sold it in school supply stores, and I so desperately wanted to be cool enough to wear it. It was like everything that came afterward was acceptable because these groups opened a new door.

Seo Taiji and Boys were decidedly hip-hop. What do you think inspired their style, which we can now say became the beginning of K-pop fashion?

Mirim: The music. Idol fashion follows their musical genre. That’s the same then and now.

Gee: It’s comprehensive of multiple things rather than one single source of inspiration. Musicians are often inspired by other musicians or their genre, which shows in their work. That is then expressed through their clothing, and when [I work as a stylist for these idols] I come in to add expertise to that. It’s a coming together of experts from different areas, creating a new style and thereby a better, more interesting result. You could never succeed by copying a certain style, so idols take these various elements and make it their own.

South Korea underwent a lot of cultural and political change during this period, with the 1987 Democratic Uprising, the 1988 Seoul Olympics, and the Asian financial crisis. How do you think these sociopolitical events impacted the entertainment industry that eventually gave rise to K-pop?

KB: With entertainment or even sports, whenever there’s a big economic event, consumer spending behaviour changes, especially when people are recovering from a bad economy. If you look at early ’90s K-pop – and even K-pop now, post-pandemic – everything has gotten flashier.

Gee: The way I see it, entertainment is a forever business. Even when the economy is bad, or when it’s politically unstable, people always want to be comforted or cheered up through music. I think every economic and political depression is closely correlated to this kind of industry. People want to find an outlet. The current idol fan culture is this reaction against modern day problems and young people wanting to find an outlet, to hold onto something. When you try and analyze K-pop from the outside, it might look like it was a sudden success, but this is clearly a business that had the potential to succeed for decades. And Korea as a society, we have this collective tendency to do our best in everything. We can survive anywhere in the world.

Before Korea became a global phenomenon in fashion, music, television, and cinema, there was Hallyu that swept Asia in the ’90s and 2000s by way of Korean dramas. Why and how do you think Korean content was able to gain so much popularity abroad?

Mirim: Korean dramas gained popularity when they started being exported and distributed in China. Korean content was welcomed because there were a lot of regulations around Chinese content at the time. In Korea, we had many Number Ones – whether it was in music or television – but our market is comparatively small, so there was always a lot of cut-throat competition.

KB: That’s why K-pop became so famous, since the Korean market is small and entertainment companies started looking to foreign markets. Compared to somewhere like Japan where they have a larger domestic market and can stay within.

‘Kids used to sneak out or run away from home to audition and train to become a K-pop idol. But these days it’s become a chosen profession.’

What distinguishes K-pop idols from other celebrities?

Mirim: When I worked as an editor, the reaction to editorials with actors and idols were very different. Idol fans are more action-oriented. They proactively jump in to support their idol and there’s a very strong mentality to make their favourite group or member the best. Let’s say we had an actor on the cover one month and an idol the next, and they were both comparatively popular. But there’s a big difference in direct sales of the magazine or the number of likes and comments when it comes to idols. We would shoot different cover versions for each member and they would all sell out offline.

What’s the source of this solidarity K-pop fans have with each other and their idols?

KB: The idol fan culture is really developed here. In the U.S. for example, if you like a musician, you might just listen to their songs or go see their performance. But with K-pop, there are a lot of other activities you can participate in as a fan. There are fan signing events and album merchandise. There are a lot of programs to strengthen and sustain fan activities.

Mirim: That brings more opportunities for fans to communicate with their idols more actively.

While it’s common nowadays for K-pop idols to also act in film, TV, or live theatre, that was not always the case. K-pop idols started disrupting other areas of the entertainment industry within Korea before they went abroad. How do you think the perception toward idols has changed over the years?

Mirim: Idols nowadays are influencing diverse categories, not just fashion and TV, but also art. There definitely used to be pushback and judgement against that at first, but now there’s a mutual need. Idols need to partake in diverse activities and these other industries also gain lots of new exposure through them.

Gee: It’s changed a lot over the last 30 years. Back in the day, when a singer crossed over to acting, people pointed fingers right away. A lot of idol members tried to act in dramas and not all of them might have been good, which became controversial. But there are exceptionally talented artists who also succeeded in acting and yet it took 30 years for people to see that and accept them. The idol trainee culture also changed; whereas before, aspiring idols only trained to sing and dance, now they master all these languages and they’re ready to also act. The older generation of trainees used to face a lot of resistance and opposition from their parents. Kids used to sneak out or run away from their homes to audition and train. But now, the K-pop idol has become a chosen profession. Parents are willing to support their children – if they’re talented and show potential – by whatever means necessary. Succeeding as an idol is incomparable to studying hard and going to a good university then getting a job at a company on a decent salary. BLACKPINK just got honorary MBEs in England. They shine and honour entire nations. That’s a whole other dimension of success. There are still some further improvements to be made in terms of how we look at celebrities, but our general perception of them has changed in a fundamentally positive way.

What about the perception towards K-pop stylists and K-pop fashion?

Gee: I majored in fashion design and everyone tried to talk me out of becoming a stylist. We used to be called ‘coordinators’ instead of stylists and would take care of everything including hair and makeup. There was this image of stylists as people who were looked down on; someone who was always waiting on the celebrity. But while I was at YG [Entertainment], a lot of that changed as our artists started dictating trends. Back around 2006, retailers such as Boon the Shop refused to lend musicians clothing, only actors. That infuriated me. It made no sense to discriminate between actors and musicians. We took it up to the people at the top and I became the first K-pop stylist they lent clothing to. Korean magazines also used to never let external stylists style their editorials, only editors. But I thought that was unfair because I also worked hard and I was respected for my work. It was crucial for me to manage everything related to our artists’ visual representation. So I became the first external stylist that did editorials for Vogue Korea, with BigBang. Editors had such pride back then, but I’m grateful they allowed me.

‘The relationship between K-pop and luxury fashion completely changed in 2016, after G-Dragon became Chanel’s first Asian global ambassador.’

There’s this saying that there was K-pop fashion before Gee Eun, and K-pop Fashion – with a capital F – after Gee Eun. Can you talk about the evolution of K-pop style?

Gee: That’s so funny. I’m still alive! I grew up with musicians who mostly wore stage clothing, only for the performance. Think sequin and spangles. I always thought that was a shame and I wanted my artists to be cool both on and off stage. I wanted people – and even the artists themselves – to believe that they were born cool. You can’t just throw something on someone and expect them to look natural. The awkwardness shows and people can tell. So instead of telling them what to wear I would slowly tease them on the hottest collection or piece and say things like, ‘Oh, you don’t have this?’ The curious ones would catch on and start getting interested themselves. As I said, I had to make my artists believe that they were born stylish. That’s why I never used to do interviews or put myself out there, because as soon as I do that it would discredit their own sense of style. First I do a lot of listening and self-education on the artist’s inspirations behind the music, and I try to understand the concept, and how to present these points visually. I was into punk fashion, subcultures, and vintage. I would mix and match with items you could buy in-store, switch up the accessories, and I think that’s what people are saying changed. It also made K-pop style more accessible when fans realized they could buy and wear these items themselves. That contributed to BigBang becoming trendsetters, especially G-Dragon. As soon as he wore something, replicas would be everywhere in Dongdaemun storefronts the next day. He became a fashion icon, and while there are many stylish idols, there hasn’t been another one quite like him, whom people are always curious about what he’s going to wear next. I really feel a lot of responsibility as we prepare for his upcoming album.

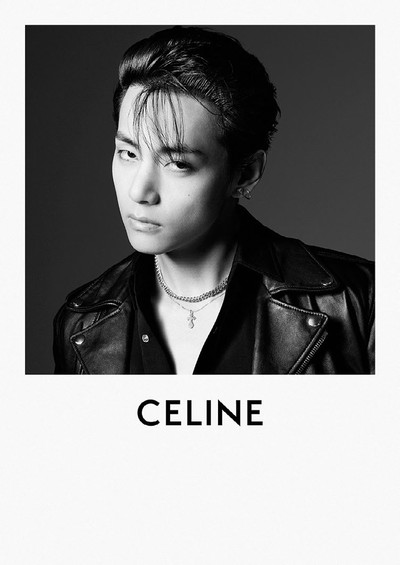

G-Dragon became Chanel’s first-ever Asian global ambassador in 2016. What was your reaction when you first heard the news?

KB: I thought it was incredible. I wondered if such a thing was possible, but at the same time, it was expected. G-Dragon was the most influential artist in Asia at the time and I was really curious how a fashion house like that would accept him. He was a true pioneer. The relationship between K-pop and luxury fashion houses completely changed after that.

Mirim: Before that, some Korean celebrities were invited to fashion events or shows, but when G-Dragon signed with Chanel – and I think Doona Bae’s first Louis Vuitton contract happened around the same time – it really moved things to the next level, beyond just being invited on an individual basis.

Gee: It wasn’t a sudden announcement for us because we had put in a lot of effort behind the scenes to make it happen. I was a huge fan of Karl Lagerfeld and Hedi [Slimane] at Saint Laurent, so at first we went to the Paris shows out-of-pocket, out of pure interest and curiosity. GD [G-Dragon] loved going to the shows and realized fashion runways can also be a huge source of inspiration. The whole lighting and performance and production of fashion week had an impact on him. I was close friends with Kim Young-Seong, Chanel’s Fabric Director, who is also Korean. If Virginie [Viard] was Karl’s right hand, Young-Seong was his left. I introduced them because I wanted Chanel to know we had this amazing artist in Korea. And whenever GD made an appearance at fashion week, he became the talk of the town, and it had this ripple effect, season after season. After a couple years doing the rounds of fashion week, Chanel asked us if GD could only attend Chanel, exclusively. But it was tricky for an artist like him to travel all the way to Europe just for one show. It costs upwards of hundreds of thousands of dollars just to bring him and all his staff over. So Chanel provided a solution, which was to sign an ambassador contract. It was unprecedented, not only because GD is Asian, but because he’s also a male artist signing with [exclusively womenswear] Chanel. It worked because Karl had a few menswear pieces per show and GD could also pull off womenswear. Such language around being an ‘ambassador’ didn’t even exist before him.

‘My goal with BLACKPINK was to sign with four major brands, one for each member. It was clear in my mind which brands matched which member.’

It took another few years until many more K-pop idols began to represent luxury fashion houses. Considering the Internet age and the speed of the fashion cycle, G-Dragon was really ahead of the game. What do you think made this possible?

KB: Before him there was a tendency to maybe not respect idols musically, but he put out really refreshing music. He dominated fashion trends in Asia and I think brands wanted in on that power.

Gee: I didn’t feel it was a long gap because BLACKPINK debuted as soon as BigBang wrapped most of their activities. My biggest goal with BLACKPINK was to sign four major brands, one for each member, because I couldn’t do that with BigBang. Menswear is a smaller market. With BLACKPINK, it was clear in my mind from the start which brands matched which member. I pitched Jennie to Chanel before their debut; I told them there is this beautiful girl and they would regret it if they didn’t do something with her. I always knew Jisoo was Dior. GD and BLACKPINK paved the road for this surge in K-pop ambassadorships. There was a couple of years between them because it took the management of these luxury houses a few years to decide if it was worth the investment and make their decision. Now, most brands’ budgets for Asia are used mainly in Korea.

Why was it so important for you to sign each BLACKPINK member to a different brand? Did you feel that would add to their success?

Gee: It wasn’t about signing for any amount of money. I simply wanted the best for each member. For example, if you think about celebrity award shows, you want your artist to wear the best, most beautiful piece. The girl wearing the second-prettiest piece would be so sad. So for every member to wear the best piece from a brand, they each had to be the best on their own. Me having an understanding of each brand’s identity, I played matchmaker. There’s a one-in-a-trillion chance for every single member of an idol group to be so unique and special. I knew BLACKPINK was like that at their debut, and they have worked very hard to maintain their status over the years. Their accomplishments are all due to their own efforts; they made it for themselves.

Do you feel the perception or treatment towards Korean celebrities, editors, and brands has changed over the years, particularly within European luxury fashion houses?

Mirim: It’s changed a lot. There used to be less than 10 editors from Korea at each show and now that number is threefold. We used to be placed all the way at the end, but now Korean editors and ambassadors get the best seats, like right next to the CEO.

Gee: Celebrities have always been treated well but there’s been a big difference in how Korean staff are treated at fashion week. The overall level of recognition and awareness about Korea has really improved. I do a lot of business with Japan, and I often ask Japanese brands or companies what’s the new hot thing to look into. They’re like, ‘Why are you asking us? Korea is the hottest thing right now!’ I think it’s really our time. As someone who started working before this boom, it’s so exhilarating. We used to get the last of the collection samples after they’d done the rounds of the other countries; they’d be all worn by the time they got to Korea. Then, with BigBang, Hedi sent us Saint Laurent collection pieces straight from the runway so they could wear it a few days later at an award show. That felt like real success to me.

There’s almost no luxury or beauty brand without a K-pop ambassador now. What are the biggest pros of this?

KB: The biggest pros are social media engagement and influence. And I think it’s helping change a lot of beauty standards. Korean celebrities used to be marketed in Asia only, but now you can find Hoyeon [Jung]’s billboards in Paris or BLACKPINK and BTS in the middle of Times Square. There’s more acceptance towards Asian beauty.

‘Korean celebrities used to be marketed in Asia only, but now you find Hoyeon’s billboards in Paris or BLACKPINK and BTS in Times Square.’

What about the cons? Some ambassadors sign as whole teams rather than as individuals, and there have been some negative reactions against ambassadors that seem too young for certain luxury brands. Is there anything brands should change about the way they appoint K-pop ambassadors?

Gee: Fashion is extremely personal. It hinges on taste. Signing as a group does feel as though the relationship has been interpreted as a business one. They’re accepting a whole group as one image or concept. I don’t think that’s wrong though, because that might be what the entertainment agency wants as well. I am curious how signing such young artists translates to actual return on investments, considering young people’s buying power. With GD, whenever he wore a certain Chanel bag it would sell out much faster in countries like China, so you could directly see the influence. We have to wait and see if today’s younger ambassadors can have that effect. That said, you can now see the clothing and styles coming out of luxury brands is also getting younger.

KB: We were just talking about this the other day. When we first started going to Paris fashion shows with GD around 2013 – before his Chanel contract – we went to Junya [Watanabe], Saint Laurent, and other brand shows. People always asked me about him even before they knew who he was, like, ‘Who is that? Why are so many people waiting outside for him?’ I think him attending a variety of shows – before being a part of one brand – and displaying various styles made an impression on people. But now, as soon as a celebrity becomes a bit famous, they sign with a brand right away. It’s nice to acclimate to one brand, but personal style is bound to have different stages and transitions. Sometimes you like Rick Owens and other times you like Dries [Van Noten]. I’m not telling celebrities to study fashion, but to just decide and say, ‘Okay, you’re Gucci, you’re Chanel, you’re Louis Vuitton’, it limits what that individual can showcase about their own style.

Mirim: Before GD, Korean celebrities might have been invited to shows here and there, but there wasn’t a case where someone did the rounds through various runways. I arranged for GD and his team to go to some of their first shows in Paris because I wanted to shoot him for Harper’s Bazaar Korea. Him, Gee Eun, and Taeyang, another member of BigBang, were all very open to experiencing new things and had a lot of fun. It would be more ideal if people could experience a diverse range of shows and brand editorials and decide for themselves which brand they match or get along with. G-Dragon and Chanel had this relationship and process of getting to know each other and respected each other for that. That’s a great way to become an ambassador. Signing based on the contract amount is really a pity. It’s an issue of authenticity.

KB: GD was personal friends with Young-Seong at Chanel. We’d always go say hi to her and Virginie [Viard] and gift them our Nike collabs. GD would just have a casual conversation with their shoe designer and talk about what he liked, and Chanel would actually make samples for him in that style. Their relationship was really genuine. It was good timing that he and BigBang were very influential in Asia, and there were people around him like Mirim and Gee Eun to make editorial content around that. There was a mutual desire from all parties to want to highlight their work and they had each other. Korean fashion really changed during this time.

Mirim: In the case of NewJeans too, they didn’t designate the whole group to one brand; they considered each member’s characteristic and matched them to their respective brands accordingly. I think that’s a good example, where each member gets to stand out and it’s a win-win with the brands.

Do you think this K-wave is a fleeting trend or something that’s here to stay?

KB: The quality of K-pop and K-cinema is getting better and better, so it’s here to stay. Other countries will also continue producing high-quality content, and in the end the world will become more diverse culturally. If a certain part of the world, or race, dominated culture before, that structure will now be shattered.

Gee: It seems like there is a movement and effort to systemize K-pop culture so it can last in the long-run. If this process of training talent and producing groups can be systemized and applied in other countries, that will really prove K-pop’s worth. The fact that companies are experimenting with training diverse individuals shows that many industry people believe in this potential too. I read in an article recently that Billboard created a separate award category for K-pop and I didn’t like that. Why separate K-pop from other genres? It’s confining K-pop to one small category when Korean idols are just as, if not more, talented, and can be judged and voted based on the same fair standards as other artists. Now is the time for us to continue marching forward.