The A&R guru behind Kendrick Lamar and Drake on why ‘music sells fashion better than anything else.’

Interview by Rahim Attarzadeh

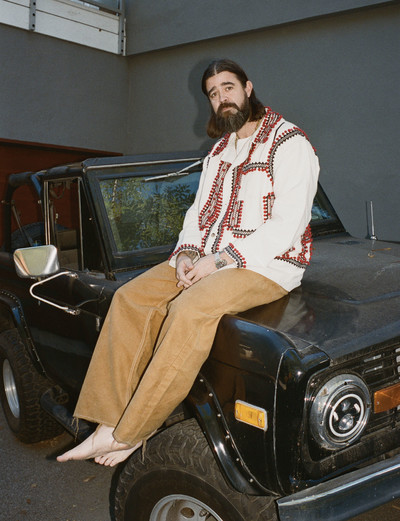

Photographs by Max Farago

The A&R guru behind Kendrick Lamar and Drake on why ‘music sells fashion better than anything else.’

A&R people have long been the talent scouts of the music industry, the outriders, whose choices map the route for record labels to follow. And just as the industry has been forced to reinvent itself in the wake of the streaming revolution, the enigmatic role of the A&R has dramatically evolved: from anonymous gatekeeper to tastemaker, talent manager, cultural connector. Brock Korsan incarnates the spirit of this new generation, channelling the zeitgeist through a coterie of collaborators who themselves embody the seismic shift of hip-hop from subculture to the mainstream: Kendrick Lamar, Drake, Travis Scott, Omar Apollo, ScHoolboy Q, The Alchemist. Having held positions at Warner Records, Def Jam Recordings, Atlantic Records and Columbia Records – or, as he calls them, ‘the big four’ – the West Coast impresario has been at the forefront of an industry increasingly engaged in cross-category collaboration, where musical artists emphasize their visual presence and personal brand, and fashion amps up its embrace of spectacle and experience. Think Kendrick Lamar performing at the Louis Vuitton Men’s Spring/Summer 2023 show, or Travis Scott’s Cactus Jack Summer 2022 Dior collection. Korsan’s modus operandi is to help musicians break the cycle of studio, album, promo, world tour (repeat), to explore the fertile overlap of film, art, fashion, design, curation and entrepreneurship. And he’s a well-placed evangelist for this multi-disciplinary approach, as co-founder of No Vacancy Inn, the globetrotting creative collective (alongside Tremaine Emory and Ade ‘Acyde’ Odunlami) where music, fashion, and nightlife collide, bringing musicians such as Frank Ocean and A$AP Rocky together with creatives like Tom Sachs and Matthew Williams, while collaborating with Marni’s Francesco Risso for a 2023 capsule collection, or on collections with Stüssy. System caught up with Korsan to discuss how to garner attention in an oversaturated market, and why no artist really wants to be ‘independent’.

How would you describe what you do?

I’m an artist helper. If you want a technical answer, I’m A&R. I feel like I’m somebody who gets an artist to their destination. I could be a gypsy cab, I could be a rickshaw. I find artists and talent that I’m attracted to and I assist them in getting to a place where we all feel that they should be.

When did music and fashion become part of pop culture? And when did pop culture become fashionable?

Ironically, individuality or expression through clothing is usually born from wanting to be someone else. For me, and a lot of people that came from my demographic, MTV coming out enabled you to actually see a visual representation of the artist that you were listening to. Whereas before there was TV, concerts weren’t televised and we didn’t have 24/7 access to music information like we do now. You would see artists on tour or read the GQ or Rolling Stone article and that formed your gateway into that world. Obviously, we didn’t know that artists were being styled, you were just led to believe that was how they looked all the time. Music sells fashion better than anything else. Music and fashion is right shoe, left shoe. You can’t really dress like your favourite basketball player every day. You can’t wear sports uniforms everywhere you go, so you have to look to musicians for inspiration. It’s been that way since the 1950s. The starting point for the emergence of pop culture shows music as the dominant catalyst for sociocultural awareness, making us, the consumer, become increasingly aware of image as time and technology progress.

As someone who operates outside the conventions of traditional A&R, what draws you to such disparate projects?

I’ve always had a keen eye for aesthetics and it’s something that has come naturally to me. I’m very opinionated about things that I have a distaste for, which makes my process easier. If I see something that I like, I will get involved. I don’t see any limitations just because I’m A&R. That’s just how I am. It’s more exploratory for me. Everything I do is driven by an underlying curiosity. ‘Is it fashion? Is it music? Is it art?’ Well, everything is a by-product of the ‘Big Three’ nowadays, because we draw on all of those things when we collaborate. It’s the new hybridity and I like to think I operate between all of those practices. That could be because music has become relatively easy for the current generation to navigate. They are the consumer and they want more. When I was growing up, we weren’t necessarily afforded that luxury. People consume music in a similar way to how they consume fashion. If I can develop a small but discerning microcosm as to how I ‘feed the consumer machine’, then that’s progress; it’s not about fighting the machine, it’s about how you feed the machine. I see things and I act upon a sense of immediacy. If there’s something that I like, I can see how a collaboration could take place long before the ideation phase.

‘I’m an artist helper. I feel like I’m somebody who gets an artist to their destination. I could be a gypsy cab, I could be a rickshaw.’

What do you think about those stereotypes of an A&R role and how do you think the practice has evolved today?

It’s completely different now. No one is currently discovering anybody and then signing them to a label. Everything’s done prior to signing. Good, bad, or indifferent. It just means that everyone has access to the same information, and music is being broken down and consumed in different ways. No one signs up to music they don’t like. Now, with the blurring of music, fashion, art and overall product, it’s far more difficult to navigate an oversaturated market and therefore far more esoteric. There are so many artists making music now. Before, you had to put up a lot of money, go in there to create a demo with a glimmer of hope that someone would listen to it. You didn’t have the same access that you have now. It was more a case of whether you could afford to buy a microphone at a Best Buy and say, ‘Okay, I’m gonna make music today.’ You had to save up a bunch of money and practise with your band in a garage and then scrape up more money to cut your demo. You already knew the songs you were cutting way in advance, you practised them a million times.

To what extent has the influence of social media and technology made the process less discerning, or led you to believe that people don’t really have an opinion at all?

It’s not so much social media but more the immediacy of access to technology because it’s ultimately software that has made the artist discovery process feel more cosmetically manufactured. The curiosity of people to think naturally, or show any instinct has become a hindrance to the process. Maybe it’s a money thing. I’d like to think what I do is fuelled by curiosity, or shrewdly maximizes the potential of an artist’s creative reach but that has changed the way that A&R operates. You’ve got the big four labels. How many A&R guys can you have in those companies to scour the earth for artists, or songs, or people that are all logging on and marketing their work in the same place? So, discovery becomes increasingly data-driven. It changes the pure artistry perspective of A&R because I might hear something that I like and think that that artist has the talent to break through and I go to sign them to a label and they look at me like, ‘There’s not enough data here, there’s not enough money being made on it to suggest that they deserve this deal.’

So, the data analytics, or technology-driven approach you’re describing when it comes to artist development has in some respects made the music industry feel more ephemeral?

Yes and no. If you look at any of the artists that are hugely successful, they’re not data discoveries. The overnight stuff… the artists that just put out a song that immediately goes astronomical on the internet, or on TikTok and all this kind of stuff, they don’t tend to be around in a few years. That’s the harsh reality of those scenarios. The internet has given this power to champion things that are more polarizing. I call it quick fast food, or McCool. With everything being viral, that type of bandwidth is impermanent. There’s a viral moment every other day. There’s a dichotomy here because whilst we recognize the ephemerality of the ‘overnight digital success’, the idea of what is deemed successful because of the internet can be applied to almost anything. That viral success story feels to me like an entry-level marketing tool. Data made cults global – everybody’s already bought their favourite band T-shirt, so it’s up to the music industry to give you a reason to buy another one.

I would like to address the debate surrounding the empowering of creativity within music. On one hand, there is the belief that the big label is king, and within the label there are moveable pieces. There is another school of thought that the independent labels have more influence because they are more curatorial in the talent they decide to work with, driving artist equity and commercial strategy. Where do you stand on all this?

I think that all of the major record labels used to think like independent labels at one time because they were independent labels. They just ended up getting major funding. I think what’s great about the independent labels like XL, Caius Pawson’s Young, even Kendrick Lamar’s [previous label] TDE is that each one presents you with their lens and a curated group of artists that they’re personally attached to. They shift art-market practice across broader levels of society. The independent labels provide connoisseurship because the people who work there are connoisseurs within their respective practices. Each time they sign a new artist, they are making a rare and selective acquisition, which is the same to them as buying a Rothko or a Basquiat painting. You’re getting somebody’s taste. If I started a label right now, I’m putting out stuff that represents my taste. You’re not going to see 55 different types of artists on my label that run across the board. Those independent labels that I referred to have all been born from the perspective of their founders. I don’t think an A&R goes to XL trying to sign a death metal band.

‘‘Is it fashion? Is it music? Is it art?’ Everything is a by-product of the ‘Big Three’, because we draw on all of those things when we collaborate.’

How do you think the music industry has evolved over the past decade? Where artists are now being described as ‘multi-hyphenates’ collaborating with clothing brands and creating beauty products?

I think that’s a natural progression for artists. Artists and musicians have always been great commodifiers. So, I think the leverage they have now is much greater, and they know it. It only works in the long-term if it comes naturally. It’s like T-shirt brands, I don’t really think that anyone needs another T-shirt brand. T-shirts sell because the consumer identifies with the person behind the canvas. Take Supreme, for example. In truth, a lot of people who buy a Supreme T-shirt don’t really have an opinion on the design but they identify with the brand so they sometimes buy it. If those same designs were to have a different label on them, people might pass them by. A great artist is like an influential brand: they create beacons of affiliation because there’s a lot of sludge out there. I don’t think everyone needs to go and carry a product with their name on it but I feel like if you have an inclination to do so, and you want to create a product that is either not out there, or better than what is currently out there, then I think that is honourable. Travis Scott is a brand as much as he is an artist, or as much as Dior is a brand, or as Damien Hirst is a brand. They’re all brands and that goes back to the new hybridity I was referring to. We’ve all been made into brands by audiences identifying with us as a kind of avatar to navigate the current pop culture landscape. There’s no denying that people are here right now to get money, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. If someone is going to give you money to put your name on something, I don’t know a lot of people who are going to say no.

The fashion industry has become an important revenue stream to musicians. In the past, collaborating with luxury brands was considered ‘selling out’. Now that this intersection feels part of the norm, this kind of work is no longer a necessary evil, rather it has become a fundamental brand and artist-building strategy. What are your thoughts on this?

I think it’s more to do with the cross-collateralization of fan bases. We live in a time where everything is for sale. Artists put out a ton of material these days. Brands are going off-calendar more than ever; putting up special products… amidst all of the things for sale, how do you create demand and how do you not get lost in this sea of consumerism? Even as a popular brand, you have to constantly come up with ways to flag interest. So, to help people know which artist they should be listening to, artists have been inadvertently marketed as ‘default guides’, or brands. What we are seeing today is the evolution of branding in order to maintain desirability over a captive audience that craves anything associated with their beloved artist. That’s a way to take a fan base to another fan base or to democratize strong fan bases and bring them together to create cultural capital. I don’t think that music and fashion can operate in an anti-establishment way anymore because of this hybridity between disciplines. In the 1970s, when artists were concerned with presenting an image of themselves as anti-establishment, this generated an uncharted sensation to be in a place where those establishments weren’t deeming you important. Nowadays, everyone craves importance. Who’s willing to say ‘fuck that’ or ‘fuck them’?

That doesn’t seem to happen so much anymore…

Because they’re being paid attention to now. Everyone has a voice now. The music industry was fucking easy compared to how it is now. It must be problematic being a teenager because now everything is already out there for you. When you can’t have something and you’re young, if you don’t like it, you’re therefore not going to force yourself to like something. You’re not going to sit there and constantly carry the flag against it. Whereas if you’re an aspiring artist and you feel overlooked by a label that you really want to be looking at you, you’re going to do everything in and out of your comfort zone to create waves. So, I think a lot of it was having a big disdain for something that represents something that you hate. Luxury brands are tapping into artists more than ever to sell things and artists are contractually being paid all this money to wear these brands. It’s a situation of, ‘Why don’t we work together and figure out a way to make more money?’

‘Each time an independent label signs a new artist, they’re making a rare and selective acquisition, which is the same to them as buying a Rothko.’

Do you think that the artists you work with have to do more than the music itself to reach mainstream audiences and achieve what is deemed successful?

We’re living in an era where you walk around and see people locally wearing that Balenciaga T-shirt more than you do wearing that Arctic Monkeys T-shirt. The music industry has to be receptive to that. You could see the cultural pathways of this consumer phenomena arising through Kanye, the Kardashians, Nike x Off-White, Frieze Art Fair, Kendrick performing at Louis Vuitton, Coachella… There’s no one particular event or moment because a global phenomena is a collective cultural and financial pattern. Artists have to do more than the music today. I still think there’s more intrigue for mystery as long as the art is marketed on the level that it’s meant to be on. You can’t deny good music, there’s no way to hide it. Songs that travel the globe, anthems, ‘music of the highest calibre’ – that shit doesn’t fly under the radar. And once that artist reaches their optimum musical output, that’s when the adjacent floodgates you’re referring to open themselves up. You don’t just have the internet and Instagram anymore, that’s not enough, you’ve got five different social-media platforms, you’ve got Twitch, you’ve got all these things that are now part of the consumer’s handbook. These all count towards measuring artist credibility. Social media is being treated as a precious artefact to monetize art.

Have there been moments when you find it problematic that an artist can record what you think is the greatest record of their career and yet, they are being encouraged to do more outside of the actual music to reach the label’s expectation of global success?

I think it depends on the artist. You have Drake who is one of the biggest artists in the world and he’s very forward-facing, he’s very active on social media, you see him everywhere. You have Kendrick who you don’t really see that much, his music and live shows do most of the marketing so he doesn’t have to. You have Travis who moves tons of products; he’s one of the biggest artists in those terms. All these artists are different and it really is an extension of their interests, so it has to be natural. You can’t sell something that’s not part of the aspirational evolution of the individual artist. You have J. Cole, who’s one of the greatest rappers of all time but he doesn’t give a shit, he’s not playing that game. You have The Weeknd, whom I don’t know if he’s ever done an in-depth interview but his music is everywhere. You don’t really see him. You don’t really hear from him, you don’t really know him. You don’t know Abel, you only know The Weeknd. You can’t smell any suspicious motives coming from any of those artists. There’s no commercial stench. The greater the artist, the greater their contribution to the zeitgeist around them because they know how to move between this high-speed culture that has proved the ultimate career challenge for any aspiring creative.

Do you find that artists such as The Weeknd have this ‘intentionally absent’ aura to maintain? Has this made it difficult for them to change their persona as their influence grows, where they may have a desire to venture into other fields? Does that make the allure less alluring?

That’s a good question. The quicker an artist commercializes themselves, the stronger the connection with their audience because they have globalized their monopoly on their own terms. That means if they want to change their persona, or take on a collaboration, because they aren’t the new kids on the block anymore and they’ve earned a certain degree of trust, they can move between this landscape of expression through hybridity. As long as the music stays first and remains great then I think all other avenues are open. However, it could be a case of, ‘never meet your idols.’ The mystery is part of the allure. It’s a case by case thing. We always think we want more from people until we get it. That’s the human experience. We, the consumers, are ‘culture vultures’ – that’s until we’ve consumed all of our prey.

‘We’re living in an era where you see people locally wearing that Balenciaga T-shirt more than you do wearing that Arctic Monkeys T-shirt.’

With that in mind, what are the important factors for an artist’s longevity?

Experimentation, curiosity, not being afraid to fail and not trying to please everybody. Knowing how to dip in, do something, drop out, and circle back again. Knowing that you can do that and you don’t have to make so much right here right now to gain traction. Where there used to be a dozen competitors, there’s now a multitude. I mean, it’s the same with fashion. How many aspirant stylists are there out there? Everyone’s a creative director, or an art director, or a blogger, or an influencer. So, with that in mind, and given the repetitively cyclical nature of these creative constructs, it can actually become easier to stand out if you ignore the sea of competition, or you bite the bullet of robo-culture. The way in which an artist presents their work has to become intrinsic to their whole formulation. The music they play has to embody an entire expression. Longevity is subject to the totality of an artist – it’s the opposite of riding the crest of a current wave but rather orchestrating viscerality into presentation.

Have there been situations with the artists you work with where you’ve become a close adviser, part-time therapist and casual best friend?

That’s usually how it starts. I think people are very leery. Before, people just wanted to be signed by labels. That was the easiest thing to get done. Now everyone wants to have loads of ‘friends’. People want to be noticed by everyone around them. They usually have an entourage and I’m sensitive to the fact that I’m someone who has a reputation – and I think it’s a good one – for helping artists, especially artists that most people once deemed anomalies. There was a time when Travis Scott was an anomaly. Need I say any more? No matter how much you care about an artist or whether you’re an ‘artist-forward’ person, you still work for the big, bad monster.

The big, bad monster being the record label – the industry?

Yes. You know, the one that wants to take your art and put glitter all over it and sell it all over the world. By the way, that’s what they all fucking want. However, the labels want to do it their way. Most of them have zero idea how to do it because they don’t want the artists to take their time or do it with the music that they want to put out. There’s this constant struggle and I get it, because I see both sides of the conundrum, but I’m always going to be a proponent of letting the artist do what the artist needs to do to get the music to a place within the upper echelon.

There’s a juxtaposition at play here, because on one hand any major record label wants to monopolize every artist they sign, or buy in to cash out. On the other hand, with the artist discovery process being driven by social media, artists are less dependent on being noticed by one label. Technology gives them options they wouldn’t have had 30 years ago. Would you say that artists are now able to make more conscious decisions?

Here’s the thing: no one’s that patient. Everyone screams ‘I’m independent’ and that all sounds fucking amazing but it doesn’t resemble much sense of reality. I don’t know any artist that doesn’t want to be the most important, or the biggest artist in the world, or have their music reach and be loved by as many people as possible. Any artist that says they’re not, I don’t believe them, I just think that they’re fucking scared. They’re scared to do what it takes to be on a level where you’re being rejected by the establishment. Or scared to do what it takes to get to that point where you’re being offered a performance at the next Louis Vuitton show, or a collaboration with Nike. It takes a lot of work to be a huge global artist. There’s a lot of legwork done that does not involve any music whatsoever. Some people are going to be like, ‘I’m cool with my music living where it is and reaching who it reaches, and I’ll travel and tour and I’m okay with that.’ But if any artist tells you to take any one record that they put out and not have it be the biggest record in the world, you’re telling me there’s an artist that would say no to that? I think not.

How do you know when an artist that you’ve discovered is at that tangible moment you’re describing – when they’re ready to play on that level?

That all starts with due diligence. An artist needs to reach a point of self-maturity where they become innately aware that the label has made a judicious acquisition without losing themselves in the opulence. It’s the same as buying a Sterling Ruby quilt. It would be easy for me to be snobbish about it but that’s not the point. It’s a matter of when they’ve paid their dues, they’re then ready to enter that level you’re describing. Or, they’ve made a song that piqued my interest enough to think, ‘Okay, this song is the predominant genesis for everything that’s going to come after it.’ Those are the moments that I look for in the artists who have the tangibles to succeed. When I heard Bakar for the first time, I couldn’t put a trace on him but when I heard the song Unhealthy, I felt he was onto something and this is the precipice of his musical blueprint. This is like the strand of DNA that’s going to mould the rest of his career.

‘If you’re making music and you don’t look the part then you’re not giving fans the full experience, because it’s all entertainment at the end of the day.’

When we first spoke about putting this story together, you mentioned how you’ve found yourself in situations where an artist has come to you for styling, or ideation around their image, where your relationship exceeds any limitations surrounding the traditional A&R role – certainly transcending any musical advice. Can you expand on this?

Myself, Acyde and Tremaine are all very different with our own personal styling but we’re all very staunch about it at the same time. It’s a situation of, ‘We’re all cool now. Everyone’s got cool.’ Because the manipulation of identity has become such standard practice, so how do we make what you’re referring to feel a little less anodyne? We have opinions on how people look and how we look, so I feel like it’s my duty to give these guys a leg up in the world they’re playing in. We can’t be walking around with an artist that doesn’t look right.

Which recording artist have you been most impressed by in terms of their input into your work together and their creative ambitions?

I’ll give you an example. When Kendrick was recording good kid, m.A.A.d city, his reference was: ‘I want to make the best album ever made, you know what I’m saying?’ That was his vision and when somebody tells you that, you know they mean it. When somebody tells you, ‘I’m going to make the best album ever made’ as opposed to, ‘I want to make the best album ever made’ you know what kind of ride you’re embarking on. It goes back to what I was saying about an artist’s ambitions and reaching that esoteric stage of self-awareness.

Do you think that can still be defined as challenging the system? Do you think it’s a healthy thing?

Widening the conversation or widening our cultural lexicon through the democratization of culture is always a healthy way of thinking even if everything is now so grossly commercialized. When an album like good kid, m.A.A.d city reaches those heights, that should be the goal every time. Who wants to go into a studio and say, ‘I just want to make a good album.’ Do you want to work with that artist? I don’t! When someone like Kendrick says that, you know he’s going to do everything it takes to get there.

Have there been instances with the artists you work with where your role has segued to how they want to supplement their core income, or is it more often a question of you guiding them towards specific opportunities that you feel will be beneficial?

If an artist wants something, or they have an idea and I have the key to that gate, I’m going to open it. Or if I have an idea for an artist and they may not see themselves in that way, my job is to drive that home. That’s literally my fucking job. It’s different because it spans so many areas but if my job was to only help an artist make music and I have a bunch of different avenues for them, then I will give them the best possible chance for success and that means anything that the artist is involved in. Everybody wants to be on the inside. That’s what’s driving it: the artist feels they are on the outside and they want to be on the inside. It’s connoisseur culture and everybody wants to engage with it. My interactions with an artist are curatorial. It is engagement work so that the creative result has an interactive quality that audiences can see manifest through art practice.

What do you think about those artists who are more concerned with the intersection of entertainment and fashion?

How many actors have you seen try to make music and it doesn’t work out? So in my specific field of duty, I’ve noticed that it’s much easier for a musician to become an actor than it is for an actor to become a musician – unless you’re Joaquin Phoenix playing Johnny Cash. Whereas fashion makes everything easier because it creates this social safety net. It has a higher bandwidth. I think it’s easier for a top-tier musician to have a clothing line than it is for a Martine Rose to make an album. What we’re dealing with here is fandom. Clothing brands create avatars of affiliation because people buy into labels. People queue outside stores and the only thing that brokers this demand is brand identity. If you took all the labels out and placed them in a stockroom, then consumers would have to think whether they actually like the product before buying it. Fandom is the CliffsNotes to culture. If you have a fanbase, then you can sell things. If you have a big fanbase, you can sell more things because you’re popular. Popular culture is king. So naturally, for an artist that tours the world and makes millions per show, the idea that you could sell that merchandise outside of tours isn’t that far-fetched.

From your perspective, what does fashion offer to your artists and the services you provide them?

A sense of expression that can enhance or cement their art. I feel like if there is a connection between what you’re saying and the way that you look, then it just enforces the sentiment or perspective of the music. If you’re making music and you don’t look the part then you’re not really giving the fan the full experience, because it’s all entertainment at the end of the day. The pageantry is a part of the fabrication of an artist; if you’re an artist and people don’t want to be you then you’re not going to be very big. We’re no longer living in the 1960s, where there were what appeared like these esoteric rock stars on stage whilst the audience was still wearing everyday casualwear.

‘I think it’s easier for a top-tier musician to have a clothing line than it is for a Martine Rose to make an album. What we’re dealing with here is fandom.’

When does the acceleration of cool cease to accelerate?

People gotta wanna be you. That’s when it stops.

What do you think of instances such as when the Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist, Flea, starred in the campaign for the Dries van Noten collaboration for Stüssy? Brands such as these have been instrumental in evolving the notion of celebrity, or musician, from an afterthought to a core marketing component. How do they go about maintaining the success of this formula?

Brands like Stüssy were formed from a point of counterculture to what can now be referred to as ‘over-the-counter culture’. They found a hole in the market so they created something out of a necessity to speak for a certain demographic. Granted they became huge juggernauts because they were driven by the culture that they represented and they went to musicians because there was a cultural identifier that they weren’t tapping into. That’s truly what the essence of collaboration is until everything becomes bastardized. It becomes a money play but when it’s done right, it generates what I like to call it ‘sonic youth culture’, but that seems vintage now. Whilst instances like the one you’re describing reveal this instant connection between the youth, brand affiliation and monetization, where the quicker they commercialize them, the quicker they sell out, they originate from a point of authenticity. Flea, Stüssy and Dries Van Noten tell us something about the evolution of the youth market. Everything goes now because of this landscape of hybridity – to be esoteric is to lose your audience.

Seeing how the fashion and entertainment industries have, in parts, become much the same, if you were to strip away the ephemera and financial trappings of this intersection, what kind of industry would remain today?

If you find yourself at the intersection of art and commerce, then prepare to have your heart broken.