How a 1981 Yves Saint Laurent insert in Vogue Paris signalled a new era of fashion advertising.

Text by Jérôme Gautier

How a 1981 Yves Saint Laurent insert in Vogue Paris signalled a new era of fashion advertising.

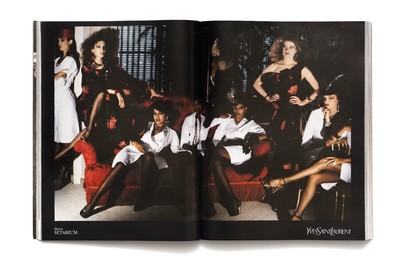

On 1 August 1981, the shutters were pulled shut and Yves Saint Laurent’s headquarters on Avenue Marceau became a maison close: a ‘closed house’ or brothel in French. But not like the one in Joseph Kessel’s 1928 novel Belle de Jour, filmed by Luis Buñuel in 1967 with costumes by Yves Saint Laurent. In the movie, the heroine, Séverine – a jaded bourgeois housewife with masochistic leanings – looks chic in head-totoe couture (except the white blouse she wears with customers) as she works in a bordello. The house of Saint Laurent, even when closed, was never one of illrepute. Behind those closed shutters that day, an entirely different scenario (or several) was being played out.

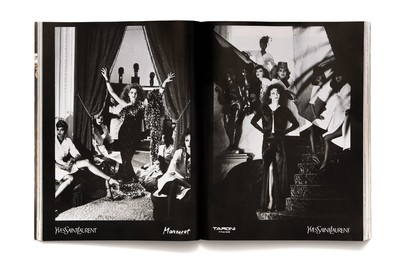

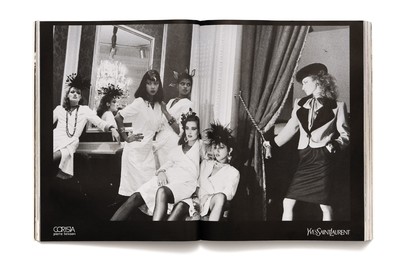

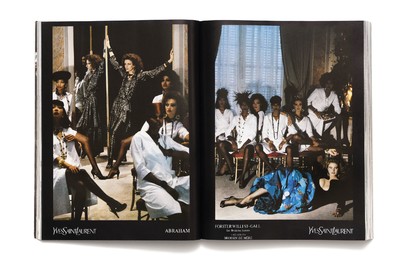

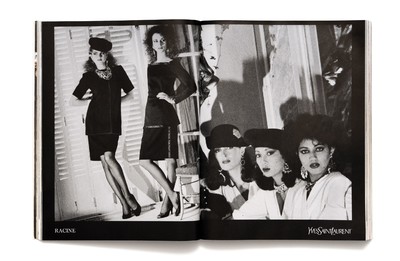

The ‘salon’ girls, dressed in white blouses, black stockings, high heels, hats, and make-up, were ready to be photographed by Helmut Newton for a new ‘Vogue Promotion’ insert or cahier for Vogue Paris. Mounia, Edia, Maria, Dothi, Kirat and Nicole were YSL’s inhouse cabine, the designer’s chromeplated gang. Only Violeta Sanchez wasn’t wearing white, as Newton had chosen her to interpret key looks from the Autumn/Winter 1981-1982 hautecouture collection. ‘I liked to give an intention, a look, an attitude,’ the actress and model recalls. ‘I would make the garment my own and become a character.’ Her femme fatale that day was – of course – the perfect fit for both Newton and Saint Laurent.

For this cahier of images, which was published for the first and only time in the September 1981 issue of Vogue Paris, Newton had once again been given carte blanche to capture and print the essence of Saint Laurent. He took the opportunity to book Jennifer Johnson, the only outsider in this little group. He had recently captured her one night at the Trocadéro in an image for the same issue of Vogue Paris, one that would become legendary: the dandy Philippe Morillon, kneeling, rolling down Johnson’s stocking; she standing, tall and powerful in a Saint Laurent suit, watched by a few bystanders peering through the darkness. ‘Saint Laurent inspired me to take some of my best fashion photos,’ Newton wrote in his autobiography. ‘I love the ambiguity of his fashion for the upper classes. There are so few people with whom I completely agree.’

‘It was a revolution, in a world speeding up and with image becoming essential. Yet at the time, photography was not considered an art form.’

Throughout his long career, Yves Saint Laurent’s designs inspired some of the greatest photographers, from William Klein, Richard Avedon, Irving Penn and Jeanloup Sieff to Juergen Teller, Inez & Vinoodh, Mario Sorrenti and David Sims. But the relationship between Saint Laurent and Newton was something else, something rarer; the work produced was the symbol of a special bond born of a mutual admiration, which perhaps dates back to their respective beginnings. Newton had returned to Europe from Australia in 1961, ready to conquer the world of fashion magazines, starting with British and then French Vogue, the same year that Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé founded the designer’s couture house. It was a moment of upheaval, and both designer and photographer were perfectly placed to capture that change. The first YSL advertisement was published in the March 1963 issue of Vogue Paris, a black-and-white studio shot by Tom Kublin. Like the promotional insert that Newton would later shoot, the page was paid for by one of the house’s fabric suppliers – that was the rule. ‘We’d call each manufacturer and say, “You can have look number three or five”,’ recalls Dominique Deroche, press officer at YSL for 40 years. ‘As they were paying for the page, we’d ask them what they wanted to present – but if they didn’t pay, they weren’t selected.’ Bianchini-Férier, a major silk manufacturer in Lyon, sponsored the first advertisement. On the page, however, its name was printed bigger than Yves Saint Laurent’s. Cue drama. Pierre Bergé’s solution was to create a series of advertising cahiers, each one created for a specific magazine and published only once. From then on, Yves Saint Laurent’s name was never too small.

In 1964, Y became the house’s first perfume and it came with a new advertisement. Then in 1966, Saint Laurent, who had made his name on Paris’ Rive droite – Right Bank – caused a ruckus with Rive Gauche, his ready-towear line. The noise served as promotion. In 1973, Pierre Bergé established the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode to recognize creative readyto- wear by designers and couturiers and industrial manufacturers; it also allowed him to update the advertising cahiers using photographers including Alex Chatelain, Gian Paolo Barbieri, David Bailey, Horst P. Horst, François Lamy, and Helmut Newton. These cahiers opened a new chapter, fuelling YSL’s communications in Vogue Paris.

‘It was a revolution back then,’ remembers Patrick Hourcade, the man who dreamed up Vogue Promotion. ‘A revolution in a world where everything was speeding up and image becoming essential. Yet at the time, photography was absolutely not considered an art form.’ Despite that, Robert Caillé, Vogue Paris’s director from 1967 to 1981, and Francine Crescent, its legendary editor from 1969 to 1986, understood the power of the photographers they revered, from new names such as Newton and Guy Bourdin to veterans including Jacques Henri Lartigue, Cecil Beaton, and George Hurrell. ‘She saw that images were in a state of flux,’ says Hourcade. ‘Francine understood that throughout her career. It meant the image took precedence over the product presented – which would end up changing many things.’

In 1971, Newton had a heart attack, an event that became a turning point in his life, work and style. Alongside a move towards masochistic erotica, he gained a new understanding of the ‘Saint Laurent woman’, symbolized by the image he later took of Vibeke Knudsen in a striped YSL suit that appeared in Vogue Paris in September 1975. In 1977, the designer asked Newton to shoot the campaign for his new perfume Opium. The photographer chose as his model the young Jerry Hall, who he had first met and photographed in 1974. Summoned to Saint Laurent’s house on Rue de Babylone, she accepted the offer – at advertising rates – to pose for the new fragrance. The original French tagline for the resulting Opium campaign – ‘Pour celles qui s’adonnent à Yves Saint Laurent’ – with its notions of debauchery, was toned down in English to become ‘For those to whom Saint Laurent is a habit’. Nevertheless, the perfume caused a scandal and incited protests in the US.

It was perhaps this Baudelarian vision of Opium that went to the models’ heads on 1 August 1981. Saint Laurent was off celebrating his 45th birthday, but in YSL’s headquarters on Avenue Marceau, Helmut Newton and the models were reviewing looks from the muchlauded haute-couture collection that had been selected by Saint Laurent and approved by the manufacturers sponsoring the cahier. Inspired by two artists close to his heart – Henri Matisse and Fernand Léger – the collection had been shown three days earlier in the Imperial Salon at the Hôtel InterContinental. No allusions, whether Fauvist or Cubist, for Newton, though. He was never prone to quotation; there was no need. ‘Helmut was an artist who transformed the world,’ Pierre Bergé once said. ‘He made us see it differently. He changed our vision, to make us touch an unknown truth. He was a master.’

‘We loved the the idea of ‘louche’ at Yves Saint Laurent, and Newton understood that atmosphere. Yet in spite of it all, there’s still elegance.’

Helmut Newton also had the artistry to capture the world of Yves Saint Laurent, and that August 1981 shoot ‘was everything Saint Laurent loved’, remembers Dominique Deroche, 44 years after the event she witnessed firsthand. ‘Models in white blouses, typical of the cabine. The world of couture, a thing of the past.’ A world that had been dying since the 1960s, but which Yves Saint Laurent never stopped trying to preserve, as a reminder of the 1950s, a flamboyant time when he was able to be close to ‘God’ or Christian Dior. ‘Dior was my master,’ Saint Laurent said in his farewell speech, in 2002, ‘and the first to introduce me to the secrets of couture.’ Saint Laurent always had a strong relationship with his models. ‘You can’t imagine the personal, unspoken relationship between a couturier and a model,’ he told Françoise Sagan in Elle in 1980. ‘They sense when my imagination is at work, when their appearance provokes this intuitive creativity in me. They are proud and delighted by it; when I work, I have a direct relationship with them more than with anyone else. They are often exhausted, but in those moments will do anything to help me.’

They were all there (except Amalia) on 1 August 1981, at the centre of the images, dazzling and disturbing. ‘There was this entire atmosphere that I still find so beautiful,’ says Dominique Deroche. ‘There are the girls reflected in all the mirrors. It’s a little blurred, a little gloomy. There’s ambiguity, there’s that “louche” side, as Betty [Catroux] would say. We loved the louche at Yves Saint Laurent and Newton understood that atmosphere. Yet in spite of it all, there’s still elegance.’ The result was Newton’s third Vogue Promotion cahier for YSL, published here for the first time since 1981. He would go on to create ten more until their replacement by what we now call ad campaigns, in Vogue Paris and everywhere else. Newton shot nine of those between 1987 and 1997, and in doing so became not only the photographer who told the most Saint Laurent stories, but also the one who counted the most.