At Paris’s Institut Français de la Mode, the synergy between fashion design and management is helping shape the industry’s future.

Text and interviews by Marta Represa

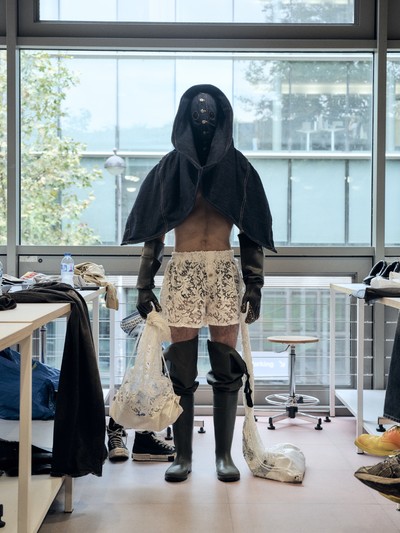

Photographs by Antoine Seiter

At Paris’s Institut Français de la Mode, the synergy between fashion design and management is helping shape the industry’s future.

The Institut Français de la Mode’s distinctive, serpentine, chartreuse-green-and-transparent building alongside the River Seine has become a modern Paris landmark. Since 2021, it has been IFM’s HQ, the latest chapter in the history of an institution that has mirrored France’s fashion industry – and culture at large – for decades.

The school was founded in 1986 by then culture minister Jack Lang in collaboration with a group of fashion industry figures including YSL’s Pierre Bergé. Its aim – to ‘strengthen Paris’s role as a global fashion capital’ by focusing on business and management – immediately attracted a roster of brands eager to co-finance the project, as well as collaborate with (and recruit from) it. Research and fashion-design departments followed in the next decade, bridging the gap between the fashion industry’s different sectors and professions, and completing Bergé’s stated mission that, like he and Yves Saint Laurent, widely considered the defining partnership of business acumen and design genius, ‘there should be no boundaries between each of our fields of expertise. We get to be better at ours by understanding those of others.’

Today, under the leadership of Xavier Romatet, the school attracts students from all over the world to its BA and MA programmes, in part thanks to the draw of its broad alumni network: creatives such as Nadège Vanhee-Cybulski, creative director of womenswear at Hermès, and Guillaume Henry, artistic director at Patou; fashion business leaders, including Bastien Daguzan, who has led Rabanne and Jacquemus; as well as countless heads of ateliers, directors, entrepreneurs and craftspeople. The result is an eclectic mix of students, all encouraged to learn from each other and explore creativity and innovation from all sides of the industry.

To understand how IFM’s boundary-pushing mission works in practice, System brought together students from the design and management courses to reflect upon their experiences of working collaboratively, and spoke to the heads of their respective departments. The resulting discussions over the following pages offer not only an insight into the nature and importance of fusing the often-competing spheres of creativity and business, but also a possible blueprint for the future of the fashion industry itself.

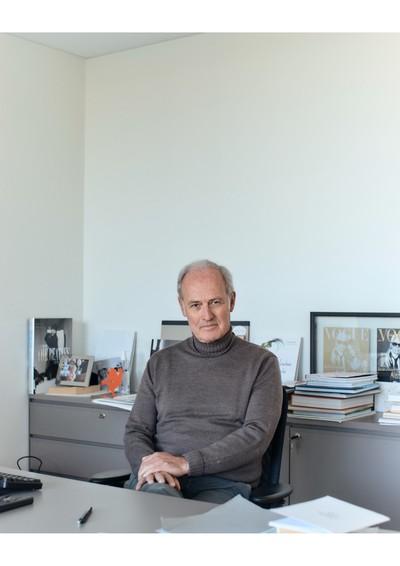

Xavier Romatet Dean of IFM

It’s not even 9am and the sky has that trademark Parisian moodiness to it, but Xavier Romatet is as upbeat as ever as he enters his office overlooking the Seine. Well known in the Paris fashion milieu for his unstoppable entrepreneurial spirit, Romatet began his career in marketing and communication as the co-founder of the Directing advertising agency before serving as CEO of Condé Nast France between 2006 and 2018. ‘It was a remarkable era,’ he says. ‘We launched Glamour, GQ and Vanity Fair, expanded into the digital realm, created era-defining events like Vogue’s Fashion Night Out. For 12 years, the industry was full of possibility.’ Until it wasn’t. ‘At some point in the mid-2010s, things started to contract and condense, and it didn’t feel as stimulating any more,’ he remembers. ‘But then Bruno Pavlovsky [president of fashion at Chanel, as well as president of France’s Fédération de la Haute Couture] reached out with a plan to reinvent IFM with more of an international focus than ever. It felt like a challenge, so I said yes.’

If, at first glance, Romatet might seem like an atypical choice for IFM’s dean, it all makes perfect sense once he shares his broader vision of the fashion industry: ‘It’s all about culture, really: knowledge, cultural references, critical judgement. Things that have gone out of fashion as the world’s emotionality has gotten more and more heightened. Ultimately, that’s what we try to cultivate here.’

No matter which pathway they choose, candidates to the IFM must prove their creative sensibility. ‘We get an average of 3,500 applicants for 600 places,’ explains Romatet. ‘We conduct around 1,500 very thorough personal interviews, lasting around 45 minutes each. That takes months, but good recruitment is essential for us. What makes us different from other schools is our multidisciplinary focus. We are not an art school or a business school, but a fashion school. And, ultimately, our mission is to nourish fashion’s creative spirit.’

‘We make our management students fluent in the language of creation, just as we familiarize design students with the business aspects of the industry.’

Marta Represa: There remains the kind of lazy notion that management in fashion is there to rein in, control or limit the creatives’ ideas. How do you counter that?

Xavier Romatet: I’ve never believed that. Not for one minute. On the contrary, it’s the creatives who should be at the helm of the industry. The essence of fashion lies in desire. We as consumers want a product for three reasons: it is original and new; it has an aspirational appeal, derived from the brand’s philosophy and aesthetic universe; and it is well crafted. Those three things are creatively driven.

Those three things have also been the pillars of the luxury industry in France for the past 20 years.

Yes. In 1998, Dior’s revenue was measured in millions; today, it’s measured in billions. That evolution is the result of a business strategy built on the foundations of a creative strategy. Luxury groups rendered their heritage desirable through design, then developed – and rolled out globally – a powerful business strategy to support that. All this time, they’ve understood that, unlike pure marketing, the luxury industry is driven by supply, not demand. The client expects the unexpected. If all you do as a brand is respond to what people already like, and replicate the strategies that first led you to success, you’re only going to thrive in the short term. Creativity is key. Of course, the bigger the brand, the harder it is to keep it at the forefront.

That’s the challenge luxury groups are facing nowadays.

That and products going from being seen as aspirational to becoming downright inaccessible. Look at pricing, look at strategy. Luxury has to remain within the realm of possibility; it needs to feel attainable. Otherwise, you’re just feeding a sense of frustration, and losing touch with the wants of society at large. That might be a conversation for another day; in any case, creativity is essential to the industry’s survival.

How do you create a symbiotic relationship between the management and creative departments within a company?

At the end of the day, it’s all about creating authentic relationships. I have always worked with creative people, people with remarkable talent and individuality, intelligence and sensitivity and I love managerial work with them, because I respect and admire what they can – and I can’t – do. But mostly, I genuinely enjoy the company of creatives, and I actually find it easier managing them than I do other profiles.

Yet we continue to hear management say creatives don’t always listen, and that in some cases, they’re unmanageable.

Oh, but they do listen, and, in a world where creatives can easily find themselves surrounded by yes men, they very often want to hear the truth. They also want to be heard, and feel safe and free in their self-expression. As a manager, you need to respect that in order to have a fruitful dialogue with them. You can’t just storm in with your business-school credentials and hope for the best. A creative sensibility is essential.

Is that what you look for in prospective students?

Absolutely. It’s what we look for in all our candidates, and also what we nurture from the get-go. In our management BA, between 25 and 30 per cent of all courses are centred around design, art history, fashion culture, and image-making. We make them fluent in the language of creation, just as we familiarize design students with the business aspects of the industry.

So they follow business-centric courses?

They all learn basic management skills, production, merchandising, as well as crafting. It’s a question of building a sense of fashion culture – and culture at large – as well as mutual respect and, of course, professional efficiency. I believe that’s what makes the Institut Français de la Mode different from other – very excellent – schools: thinking of fashion as a fully rounded industry, knowing that everyone within the industry is ultimately working towards making brands better. We definitely want our students to understand that from the get-go.

‘Managers need to respect creative expressions and sensibilities. You can’t just storm in with your business-school credentials and hope for the best.’

Are there any core subjects all students share, regardless of their pathway?

We are currently working on setting up 15 different cross-disciplinary elective subjects, ranging from creative writing to technology to sustainability. The idea is to dedicate each Monday to them, on a project-by-project basis in groups of 10 to 25, so that throughout the academic year, students from all pathways will be working together on subjects such as fashion and cinema, or fashion and performance, in every sense of the word; just exploring the many ways in which performance nourishes creation and shapes brands and their creative expression nowadays. These are particularly relevant subjects in the industry and have proven to be very popular among students.

From what I have seen, management and design students already spend time together daily on campus.

We designed this campus with that very idea in mind. The walls are transparent, so anyone can see what goes on in the classrooms and ateliers. The idea was to create a series of spaces where everyone would meet every day, in an informal, spontaneous way. It’s about the full experience rather than just a couple of workshopping hours. All year long, our main entrance hosts fashion exhibitions. Shows take place here during Paris Fashion Week, immersing students in their hectic atmosphere. So yes, it goes beyond just collaborating in class. We want all our students to get used to the creative process, to talk to one another, and to learn how to best use AI, a printing press or a sewing machine.

What active role do the city’s fashion and luxury brands play in this school ecosystem?

IFM is here because of Parisian brands; they were the ones who first financed the school, and they in turn collaborate with us as they would in a creative laboratory. The school is a hub where all the professions and players of the industry meet. That has always been my goal: to create a cultural intersection. And I think brands have really understood and are responding to that, collaborating with us in an array of organic, authentic ways. Our projects with Hermès, Kenzo, Loewe or Coperni are designed to teach our students the realities of the industry, while bringing fresh points of view to the maisons. Also, of course, they are the perfect recruiting opportunities. After all, it would be a pity not to make the most out of the fact that we are based in Paris.

And then there is the incubator.

We have both an incubator, with around 20 start-ups and designers each year, and an accelerator, with five or six brands. Louis Gabriel Nouchi, EgonLab, Marine Serre and Jacquemus have all been part of it, but it was never as much about their undeniable creative talent as it was about their capacity and readiness to build a bridge between their creativity and their business strategy. Once again, it’s about building bridges, because in this industry you can only succeed once you realize you can’t go it alone and are part of something bigger than just you. That’s the beauty of fashion.

Franck Delpal Director of MA in Fashion and Luxury Management

Dr Leyla Neri Head of MA in Fashion Design

Thierry Rondenet Co-Director of BA in Fashion Design

Hervé Yvrenogeau Co-Director of BA in Fashion Design

Sat in a classroom, among several dozen Stockman mannequins, are key members of the IFM faculty: Franck Delpal, Leyla Neri, Thierry Rondenet and Hervé Yvrenogeau. Each has had a different professional path, yet all have first-hand industry experience. Delpal is deeply involved in the business of fashion through IFM’s Incubator Program, which he founded in 2015. A fashion designer with a PhD in anthropology, Neri started her career at Gucci, and still collaborates with different brands. Rondenet and Yvrenogeau, a creative duo who graduated from La Cambre and won the Grand Prix at the Hyères Festival in 1994, have worked with Maison Martin Margiela, Jean Paul Gaultier and Balenciaga, while managing Own, their brand.

What attracts students to IFM and its programmes?

Leyla Neri: I think people who come here are attracted to two very different things at once: the specializations and how we bridge the gap between all the students in different programmes. In my case, I only have a few students who apply for the MA immediately after completing their BA. They tend to come to us after a period of work experience or even after a previous MA at a different school, like Central Saint Martins.

Franck Delpal: When it comes to the management side of things, we are competing with traditional business schools, so those who look for a different, more creatively oriented vision gravitate naturally towards us. Beyond industry specifics, they’re looking for the intangible: learning about desirability, brand image, and so on, and that’s our specific approach.

What kinds of student profiles do you look for?

Hervé Yvrenogeau: As many different profiles as possible. People from all walks of life, backgrounds and sensibilities. On the BA, we give the chance to young students, sometimes straight out of high school. Even if their approach can sometimes be naive, there is a freshness to them, and the kernel of something that can be nurtured and developed with time.

Thierry Rondenet: We had this student a few years ago who when he came to us had no previous experience within fashion, but was doing black-and-white photography. Not only did he complete his BA, he also went on to intern at Maison Margiela and is now back here for his MA on a scholarship.

Hervé: Our scholarship programme is fundamental to us; 25 to 30 per cent of our students are here on scholarships. Both Thierry and I studied at La Cambre in Brussels, a publicly funded school, so we feel very strongly about this. Fashion does not have to belong exclusively to the elites and the middle classes. On the contrary, it becomes richer the more diverse its points of view.

Leyla: But sometimes fashion remains unattainable even for the middle classes! Our fees are much lower than other schools, but for European MA students, it’s still over €24,000 for the two years. For non-Europeans, the price rises to €38,000.

Thierry: That’s why creating work opportunities is so important to us. Eighty-five per cent of our students go on to be employed within a year of completing their MA. Same for internships – the opportunities are unique. The Row recently opened their Paris studio, and immediately picked three of our students to intern. We tend to forget how lucky we are to be in Paris.

‘The Row recently opened their Paris studio, and immediately picked three of our students to intern. We forget how lucky we are to be located in Paris.’

Can you describe your different programmes?

Franck: Our management MA is short, only 16 months long, but also quite intensive. It is often the last academic chapter for students who already have an MA. It is built on four different pillars. Firstly, learning about the transformations that are currently shaping the industry through things such as CSR, technology and international markets. Secondly, proficiency in everyday operations, no matter what field they later choose. This goes from production, pricing, and liaising with factories to merchandising, analytics, distribution, or even content production and image. Thirdly, a knowledge of creative culture and the creative process, not just so that they’ll understand designers’ points of view, but also so that they’ll develop their own innovative solutions and ideas. Finally,

traditional management skills: how to brief a team, giving feedback, using Excel, et cetera.

Thierry: The BA is, of course, a whole other thing. Our work is very much angled in specifics. We create a framework and teach the basics of design, and of course, crafting. Little by little, the students start working on developing a silhouette and expressing themselves. Then, in our third and final year, our students create their collections, which are the perfect summary and expression of all they have learned.

Hervé: There are also some more unexpected disciplines we prioritize. For instance, research.

Thierry: Because they do tend to just want to do it online, which can quickly get very repetitive and limited.

Hervé: It’s important to teach research methodology, while banning things like Pinterest. Library trips are mandatory, and that transition from online to physical can be difficult. For many students, spending two hours at the Bibliothèque Nationale seems like a waste of time. Hopefully, though, they come to understand this is how one builds culture.

Leyla: For the fashion design MA, it starts with choosing one of our four pathways: clothing, accessories, knitwear, or image. All students share about 20 per cent of their classes, on subjects including human science, sustainability, introduction to business, HR, and career preparation. Other than that, it’s mostly a project-based curriculum. It’s important to us to teach in a way that reflects both the current transformations in the industry and in society at large.

Thierry: We are in Paris, but count 77 different nationalities at the school, so not being Eurocentric in our teachings is essential, for example, with subjects like fashion history.

How do you go about integrating the work that students do with brands into the wider programme?

Leyla: Brand projects are at the heart of our MA. It’s not simple, as we have to negotiate with the maisons, sometimes as much as two years in advance; establish a legal framework, for example, in case a student’s idea is retained; and accommodate the rest of our daily schedule around it. But the wonderful formative opportunity they provide makes it all worthwhile.

Franck: The fact that we are working with real-life companies in real-life cases makes all the difference. We have brands come in to brief students like they would their own teams, about subjects including brand image, product development, communication, and client experience.

Leyla: After I graduated, I went to work at Gucci in Florence, during the late Tom Ford era. I cried throughout the first week – that’s how clueless I was about working within a company. I’ve never forgotten how hard that transition was, and part of what motivates me in developing these brand projects is to help the new generations avoid experiencing that shock.

‘We have just finished a four-month project with Loewe, where the theme was redefining masculinity in the context of the men’s leather-goods market.’

Who are some of the brands you work with?

Franck: Celine, Louis Vuitton, Farfetch, Galeries Lafayette, Jacquemus, Courrèges, Coperni…

Can you talk about a recent project example?

Leyla: We have just finished a four-month project with Loewe, where the theme was redefining masculinity in relation to men’s accessories. Students had to research the gap between modern ideas around masculinity and gender and the realities of the men’s leather-goods market, by doing things like going into a store to conduct a survey. Then, they designed a bag. With Hermès, it was all about visiting the house’s archives to find carré scarves that could be transposed into knitwear. Then we did a project with Kenzo, centred around Kenzo Takada’s first few collections, which he made on a shoestring budget but with the help of his community. Students had to reflect on that, and on Kenzo’s sense of joy.

Leyla: In 2024, joy has been in short supply, and students were vocal about it. In the end, they all found ways to work within

the concept, except for one student, who researched Kenzo’s grief instead. Each student had to design a 30-look collection and produce a complete outfit, using a single material in two different ways.

What are the biggest challenges faced by today’s students?

Franck: I don’t even know where to start! The market is in a complex place at the moment, especially for luxury conglomerates. How do you make these huge structures, which are so well-established and sometimes resistant to risk and initiative, move with the times? Then of course, there is the evolution of trades, the rise of new professions, the challenges related to the transmission of crafts and savoir-faire, European manufacturing. The list is long and varied and, in many instances, potential solutions have to do with bridging the gaps between disciplines and knowledge fields.

Gal Benyamin and Caroline Baratelli

Gal Benyamin MA in Fashion Design student

Caroline Baratelli MA in Fashion and Luxury Management student

Tell us about the work you’ve done together.

Caroline Baratelli: The school was approached by Sheltersuit Foundation, which helps people in need of shelter through a range of initiatives, including providing protective, functional, warm clothing to the homeless, refugees, and disaster and conflict victims. It was one of several options for a sustainability-centred project, and we were both instinctively drawn to it, even though Gal and I didn’t know one another then.

Gal Benyamin: For me, it was a no-brainer, because it was the only project to address sustainability as direct social impact. It was the only place where we would get to help other humans directly, while the rest were start-ups, deadstock solutions, et cetera.

Caroline: I grew up here in Paris, and have noticed how, year after year, the homeless population has increased. This summer I started working with shelters, so this was the perfect opportunity to extend that work.

Gal: Same with me, I have done voluntary work outside the school, so having the chance to continue it here, with this project, has been great.

Were any other brands involved?

Caroline: Balenciaga gave us the deadstock to manufacture our product, and they also made a donation to the foundation.

How long has the process lasted?

Caroline: It’s been long. We started in October 2023.

Gal: We’re still working on it because we made the choice to continue, beyond just something to add to our resumé. In fact, we are expecting a fabric delivery from Isabel Marant this morning to make some more product!

‘We dress differently, think differently, but there is a lot that unites us. And it’s those differences that have strengthened our working relationship.’

How did you come up with the idea for your product?

Gal: At first, we didn’t have a clear idea, so we spoke to refugees and homeless people about what they needed most, what they could use. In the process, it struck us how many children and pregnant women we were coming into contact with.

Caroline: There was one particular incident, where we were talking to a woman on a cold, rainy night and she was carrying her baby. She lost her grip, and he fell. We were horrified to realize that this woman lacked something as basic as a device to effortlessly carry her baby. That immediately sparked the idea.

Gal: I remembered how my mother used this wrap, which was 100-per-cent safe. No child would ever fall from it, and also it provided a warmth and closeness between baby and mother that I feel is precious – especially in vulnerable circumstances. So we designed a baby-carrying wrap.

Caroline: Gal’s idea was genius from a business and production perspective, because it’s so simple! All we required in order to manufacture the prototype was five metres of any slightly stretchy fabric. That’s also easily scalable.

Gal: I have come to realize that, when working on a project as particular as this – indeed, anything regarding sustainability or social impact – the simpler the concept is, the easier it is to convince people to invest in it. It might seem banal, but it’s really useful.

Caroline: We have produced and distributed 100 wraps to shelters so far, and are waiting for this Isabel Marant deadstock in order to produce a new, bigger batch. It’s exciting.

What have you learned about each other and your respective work processes?

Gal: Honestly, the whole experience has been just so good. Putting aside the fact that Caroline is an amazing person, we’ve worked together really well because we completely trusted each other from the start, and we’ve known we had a common goal.

Caroline: We owe a lot of our success to the fact that our personal dynamic was so good, even though we are vastly different as people!

Gal: We dress differently, like different things, think differently, but there is a lot that unites us. And also the differences have strengthened our working relationship. When I’m doing creative work, I need to feel supported and also a bit pushed; I need someone to actually make things happen.

Caroline: It’s about validation.

Gal: Not necessarily about me getting validation directly from you, but about you creating a sense of validation from the outside. Otherwise I get very unmotivated.

Paul Billot and Léa Lupone

Paul Billot MA in Fashion Design student

Léa Lupone MA in Fashion and Luxury Management student

Tell us about the work you’ve done together.

Paul Billot: The first thing is how much fun it was.

Léa Lupone: It was unexpected because unlike most of our projects, it was short. It was with Coperni and we only had five days to complete it, so it was an intensive week to say the least.

Paul: It’s interesting to experience that kind of timeline, where you work under pressure and need to find quick and efficient ways to collaborate. It’s draining, but enriching.

Léa: At the end of the week, we had to present our concept and our product in public. That added an extra layer of stress.

What was the brief?

Léa: Coperni came to us with a question regarding product expansion. They needed us to come up with new product ideas outside of pure fashion. Of course, being Coperni, we knew innovation and tech were an essential ingredient.

Paul: We quickly knew we wanted to create something beauty-related, because it makes a lot of sense for a lot of brands, but we also wanted to offer something different from what most brands offer, and feature some sort of cutting-edge technology. That’s what inspired the idea of an LED mask. I’ve been seeing so many of them on social media recently, and the funny thing is people are not just wearing them in the privacy of their home, but making videos and selfies and TikTok dances while using them. So I thought we could give the masks different expressions: angry, laughing, happy. We called it ‘LED-moji’. It’s an innovative beauty device, but also an accessory.

Léa: When Paul first came to me with the beauty idea, it immediately set my wheels spinning. I started thinking of market opportunities, numbers, benchmarking. Then he told me about the mask, and I was bewildered for a minute. Then I realized I could make it work business-wise. For lack of a better word, I could ‘justify’ it.

Paul: Of course, you could! It was a good idea.

Léa: It was! I think our brains work differently, though. I don’t think we ask ourselves the same questions at all. It’s funny because I have never thought of myself as particularly numbers-oriented, but working alongside you I realized I actually might be! I was looking to justify every single decision in the context of the brand. I don’t know how that works on your end, do you feel like you have to justify your choices?

Paul: Not in the slightest. For us, it’s more about confronting the visual impact of what we design. How does it make us feel? How does our body react to it?

‘Coperni needed us to come up with new product ideas beyond pure fashion. Being Coperni, we knew innovation and tech would be essential ingredients.’

Often, the public doesn’t really know what it wants until it has that visceral reaction to a new product.

Léa: Totally, and our work as managers is just to interpret and contextualize that new product. In this case, we did a photo shoot and then did the presentation wearing white lab coats, for a bit of a scientific veneer.

Paul: It highlighted the innovative aspect of the product, and it was also a little bit cheeky. I was into that.

Léa: We only had three minutes; we had to be as convincing in our pitch as we were in our prototype.

Paul: Our prototype was made in plasticized cardboard, printed using the Fablab, which is our technical laboratory, equipped with 3D printers, logo-makers, embroidery machines, and a team that coaches us in their use.

Léa: I can’t believe I had never before been to the Fablab. It was such a great discovery for me, and such a great opportunity to see this school in a different way to the one I’m used to.

What did you learn about each other during this project?

Paul: I realized we are incredibly different, personality-wise, but that we can work together fabulously well by sitting around a table and sharing ideas as equals. Around you, Léa, I felt free and safe to express an idea that could have been seen as stupid or too risky. You were really flexible in your views and the way you worked.

Léa: It was important for me to make you feel comfortable, and I think sitting around a table and just sharing ideas without judgement is a great way to boost creativity, yours as well as mine. Your input was invaluable for many reasons, one of them being that your vision is close to that of the client, because it is visceral, instinctive instead of analytical. I learned that by working with you.

Paul: And it’s great to have your more analytical reactions, too, because among designers things can quickly get too… esoteric. We need grounding.

Ali Es-Kouri and Adrian Kammarti

Ali Es-Kouri MA in Fashion and Luxury Management student

Adrian Kammarti assistant professor, Fashion Theory

and PhD student at Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne

What brought you together?

Adrian Kammarti: Ali was my student, but we had already met through aesthetic affinities. I finished my MA at IFM in 2017 and am currently an assistant fashion-theory professor here, alongside my PhD in the history of art and fashion.

Ali Es-Kouri: I started my MA last year after studying computer science, and I’m simultaneously interning at the men’s merchandising department at Givenchy.

Adrian: It was another guest teacher who introduced us because she thought our views on fashion would click. We both discovered fashion through online forums.

Ali: We both have a preference for Hedi Slimane, so we immediately started discussing his Saint Laurent era after we met. I grew up in Morocco, so access to fashion was limited. Luckily, I was introduced to subcultures via the internet.

Adrian: For me, it was about Kanye West and what he wore. That, and online forums, is how I discovered the work of Ann Demeulemeester, Rick Owens, Visvim, which ultimately led me to research the link between fashion and subcultures.

Does the IFM framework enable you to explore that vision?

Adrian: Absolutely, and in different ways, such as research and publications; I love the transversal quality of it.

Ali: There are many different student profiles here, we get to share a lot and learn from each other, but also to delve into the things that specifically make us tick. I still remember my application interview. I was nervous it would all be about the luxury industry, but the faculty encouraged me to talk about things like musical references – I’m a big fan of early-2000s indie rock – and how they inform my take on fashion.

Adrian: I love finding out about the things my students are passionate about, and I love to share my passions. The way I design my classes is the same: I start from a simple idea that I find intellectually stimulating or innovative, something that steers clear from the clichés of fashion history. I want to tell my students about the kinds of movements and designers that are often overlooked: Supreme, BAPE, Cottweiler. They were decisive in shaping a whole fashion era and what came afterwards, and they need to be more present. The goal is for my students to have better knowledge than even most people in the industry. Because, paradoxically, a lot of people in fashion are not really fashion fans.

‘The goal is for my students to become more knowledgeable than most people in the industry. A lot of industry people aren’t really fashion fans.’

Tell us about the project you worked on together.

Adrian: It was a part of my contemporary-fashion course, where I teach fashion movements since 2016, with the arrival of Demna at Balenciaga, Anthony Vaccarello at Saint Laurent, and Maria Grazia Chiuri at Dior. In it, we explore the ways in which the industry has been transformed. This year, to coincide with Paris Fashion Week, we concentrated on the evolution of fashion shows. Starting with an item related to a show – photo, video, soundtrack, prototypes – we asked our students to analyse and reflect on it, in the form of an art installation.

Ali: I got an Autumn/Winter 2022 Balenciaga invite, the one that came as an iPhone. That got me thinking about the concept of the front row, and its evolution these past few years. How did it go from the press, clients and aristocrats in Cristóbal’s era to Kim Kardashian and influencers today? I researched the progressive changes through the Ghesquière, Wang and Demna eras and came to the conclusion that 2008 was in a way the ‘big bang’ year – because of the arrival of bloggers. That was when brands started thinking differently about the ways they wanted to be talked about.

Adrian: The great thing was that you presented your research by creating a front row yourself.

Ali: At our own, tiny scale. We created seating for the members of the jury and only sat one of them on the front row. We then explained the reasons for that choice.

Adrian: It was a perfect demonstration of the power dynamics at play, and a supremely creative mise-en-scène.

Ali: A scenographer guided us through the more technical aspects of it, and that was really helpful. We are students and of course, our means are limited, but that’s what inspires us to think outside the box and come up with creative solutions and presentations. It’s also really motivating to work around something you feel truly passionate about.

Adrian: At the end of the day, it’s simple: the more passionate people there are in the industry, the better fashion becomes.