By Jérôme Gautier.

‘What was extraordinary about Bourdin was that you could take him anywhere and he’d manage to take a photo that was exceptional, completely modern, and totally unique to him.’

Guy Bourdin loved the sky. He would ask for clouds and stars to be set up in the studio – sometimes even the moon. He’d also venture outside and look upwards, always happy to invite passing aeroplanes into his images. He could wait for hours for a happy accident to occur, because he knew he’d always get what he wanted.

The first long-distance journey Bourdin took was in 1948 to Dakar, Senegal, for his military service as a photographer in the Air Force. The desire to both travel and take photographs never left him. His first professional trip was to Cala Piccola, in Italy – described in Vogue Paris (May 1961) as ‘an unspoiled wild coastline’. But Bourdin was already dreaming of a very different destination: New York. He was sent there in the spring of 1966, alongside his Vogue Paris accomplice Francine Crescent (who, at the time, was the magazine’s improbably titled fabrics, leathers and furs editor) and the top model Nicole de Lamargé. Guy photographed de Lamargé wearing a 50/50 mix of French prêt-à-porter and American ready-to-wear: in the streets and avenues of Manhattan, on and under the Brooklyn Bridge, in the subway, and in the back of a limo. Nicole also posed with the kings of Pop Art: Rosenquist, Indiana, Lichtenstein, Wesselmann, and then with… Batman. The result: 38 pages of comic book-style adventures in Vogue Paris’ August 1966 issue. Bourdin couldn’t wait to get back out on the road again.

In Paris, he set about constructing his own world: a surreal universe built within his cavernous lair in the Marais and at Studio Vogue on the Place du Palais-Bourbon. Francine, now promoted to editor-in-chief since their New York escapade, worshipped Guy and gleefully encouraged his latest audacious exploits in her pages. By doing so, she brought glory to Vogue – the big, bold and grandiose jewel of 1970s Paris, in what would also become Bourdin’s golden age.

There were his photos taken from behind closed doors, and then those shot when he escaped the studio: the on-location shoots. Firstly in Normandy, at La Chapelle, which offered up an unassuming house that he’d inherited from his grandmother, as well as the beach, the railway, green grass, and the cliffs of Étretat.1 Bourdin found the shoreline’s wind and rain deeply inspiring. Another elemental figure, the sun, would rouse him to shoot the summer swimsuit collections in the winter months, capturing them in Martinique in 1974, then in Los Angeles in 1976, and in Miami during the winter holidays of late 1977. Guy was as smitten with the city’s Fontainebleau Hotel as he was with Paris’ palaces. He also loved returning to the mountains, such as Hallstatt in Austria, which he’d once cycled to in his youth.

By 1981, Guy Bourdin was both at the peak of his career and at his lowest point in life. His wife, Sybille, had committed suicide. Pummelled by life and with the taxman on his back, he was desperate to get out of France. To flee, if not to completely escape, his woes. So the Vogue Paris team began sending him off on more peripatetic assignments than ever before; some in France, others further afield. He travelled many a time with the magazine’s fashion editors Martine de Menthon, Barbara Baumel and Marie-Amélie Sauvé, and its ‘artistic advisor’ Patrick Hourcade.

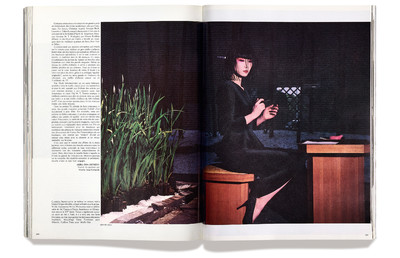

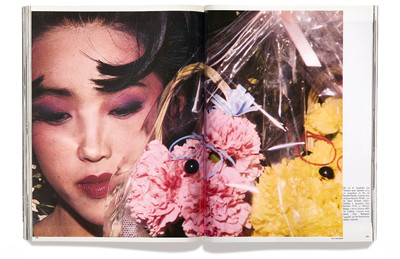

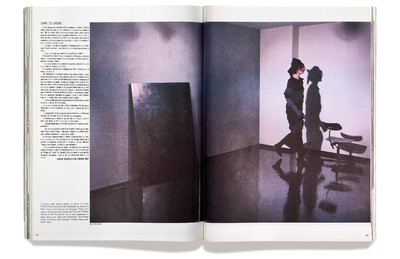

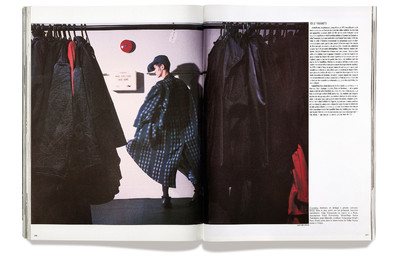

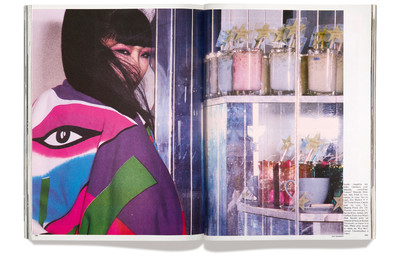

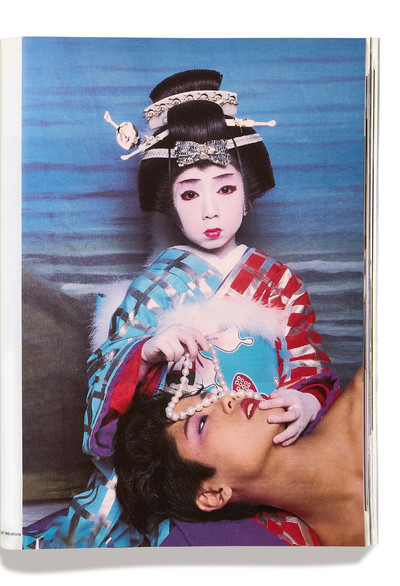

In the following interviews, the one-time travel companions share their memories of these epic journeys taken with Bourdin for Vogue Paris. To illustrate their recollections, we have selected a single Guy Bourdin story that encapsulates their experiences: the avant-garde fashion of the 1980s Japanese designers, photographed in Tokyo by Bourdin, and published in Vogue Paris’ November 1984 issue.

Jérôme Gautier: Was travelling good for Guy Bourdin?

Patrick Hourcade: Yes. Guy needed to externalise his feelings, to escape.

Barbara Baumel: It took him out of the comfort of the studio and his daily life in Paris. As a team, we functioned like a family. He loved travelling, it made him happy.

Marie-Amélie Sauvé: When you travelled with him, you had to be with him all the time. You had lunch with him, dinner with him. There was no question of saying, ‘I’m off to bed now.’ He expected total dedication. We were a close-knit group and the atmosphere was very good-natured. A bit like summer camp. I was good at doing imitations of people in those days, and so I’d imitate Guy which made him laugh. He loved those moments of just hanging out and relaxing.

Barbara: It was very joyful. Guy loved to have fun. For example, he’d have everyone on the team pick up a camera and take a photo at the same time as him. Then he’d mix up the films and develop it all himself. He made me laugh, and I made him laugh too. We really clicked, we had a great rapport.

Did he make you cry too?

Barbara: No. Never.

Martine de Menthon: He was a very, very unusual character. He could be extremely unpleasant, dismissing people he didn’t like, and, conversely, be very gentle and generous to those people he loved. Guy loved it when you made him laugh, or when you had fun together. He was a big kid who perhaps had a desire to distract himself a little. He had experienced terrible tragedies in his life, and there was a period when he just stopped working altogether. There is a ‘before’ and an ‘after’.

When did this break occur?

Martine: At the time of his wife’s suicide. That explains a lot about Guy’s work. Before then, anything went; everything was crazy, everything was free. And then after that: ‘Can I do that? Do you think I should do it? I’m going too far here, aren’t I, Martine?’ Afterwards, he always seemed afraid.

Marie-Amélie: Guy had an extremely childish side to him, in my opinion. There was something very sacred about him, and Francine [Crescent], like everyone else, held him in very high regard. But at the same time, you were dealing with a kid. For me, it was always a very ambivalent relationship.

Barbara: He taught me lightness, and the idea of not turning anything into a big drama; to work hard while always remaining straightforward; to cultivate a sense of irreverence; and to believe that nothing is impossible. He often asked for things that I thought were impossible – and yet they always ended up happening.

Marie-Amélie: Everything had to be possible. I remember Francine telling me, back when I was an assistant: ‘When Guy asks for something, you have to say yes.’

Barbara: My first trip was for a fur story shot at the thermal baths in Baden-Baden. I was [fashion editor] Franceline Prat’s assistant, and only 17 years old. Guy said to me [imitating his nasal voice and deadpan tone]: ‘Miss, you’re going to change into a swimsuit.’ I turned to Franceline and whispered, ‘There’s no way I’m putting on a swimsuit and jumping into the pool.’ She replied, ‘Honey, we’re not asking for your opinion. You’re doing it.’ So I ended up in a swimsuit, alongside the models, and he made me dive in countless times to get his photo. Because I was a kid, he deliberately teased me; he loved to provoke and make me blush. He was both shy and modest, but also very provocative and mischievous.

Patrick: He could be ironic, bordering on cynical.

Martine: He needed to create space around him that people couldn’t invade because he was incredibly sensitive.

‘When you travelled with Guy, you had to be with him all the time. For lunch, for dinner. There was no question of saying, ‘Right, I’m off to bed now.’’

Could he become a nightmare, especially when travelling?

Barbara: One time in Venice, he went completely crazy. Usually, we’d go away for about a fortnight, sometimes even a month; he loved to take his time to soak up the country. But for this particular trip on the Orient Express, we were only away for four days, which freaked him out. On the way there it wasn’t too bad. He took a few photos on the train. We all slept a bit. Then we arrived in Venice. Things hadn’t been going well with Franceline: they weren’t seeing eye to eye on the shoot and the atmosphere was very tense. Guy woke us all up in the middle of the night wanting to take a photo in the cemetery, on a bridge, in the fog, in the freezing cold. Then he photographed one of the models in one of the hotel’s boats. But it was all complicated. He thought everything was ugly and threw away the film because he wasn’t happy. On the train back to Paris he made us work all night. He went completely bonkers. He had one of the models pose for photos in the toilets. And poor Thibault Vabre [the make-up artist] was told to dress up as a train controller, posing in this rather awkward scenario with a model in lingerie. Then, to top it all off, we arrived at Gare de Lyon at 7am, after a sleepless night, and Guy announced he immediately wanted to continue shooting. Franceline was completely fed up and just left. The two models were exhausted, and the hair stylist and make-up artist finally said, ‘That’s it, we can’t take any more, we’re off as well!’

Is that why you can’t see the models’ heads in those pictures?

Barbara: Yes. He asked me to go fetch some suitcases from the Orient Express and have the models put their heads inside them so no one would see they hadn’t been made up or had their hair done. I’ll never forget it. Guy was awful! In the end, I just said to him, ‘I never want to see you again, or hear from you, or work with you.’ And I left. Next thing, I received 10 kilos of chocolate, 15 bouquets of flowers and 50 apology notes from him. That was the only trip that I’d say was truly hellish.

Who chose the destinations?

Martine: We let Francine decide, but of course we had the choice of whether or not to go.

Barbara: Sometimes it was [Vogue Paris publishing director] Robert Caillé’s choice. He was the one who chose Haiti.

Patrick: The Vogue trips were just money-making exercises. They weren’t for sightseeing. The trip to Tokyo, for example, was paid for by make-up brands. It was also done with a view to launching Vogue in Japan.

Barbara: We’d also ask Guy where he wanted to go, and he often decided. For example, we went to Hallstatt, because he loved that place and used to spend his holidays there. Martinique was also his choice: he was madly in love with Mounia, the model, who had successfully charmed him into organising a trip entirely centred around her. Except that Guy, true to his rather mischievous self, decided to bring a second model along, a blonde [Nahanni Johnstone], who was the complete opposite of Mounia. Mounia was furious and was horrible to the other girl. I remember one time we went to Sydney because his assistant, Sean [Brandt], was Australian. And around that time I met my future husband, but he’d had to leave Paris to go do an internship in the Gers. Guy knew this, and when Francine asked during a meeting in his office, ‘So Guy, where do you want to go next?’, he looked at me and replied: ‘To the Gers.’

Once the destination had been decided, and one or two fashion editors assigned, how was the trip organised?

Martine: We were basically ditched. That’s really the word for it – we had to fend for ourselves! But we were given artistic freedom with the photographer, which was both wonderful and absolutely unheard of. We could be irreverent, no one stopped us. As soon as we arrived somewhere, the concept for Guy was always about ‘discovery’.

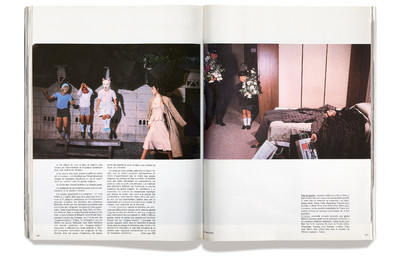

Patrick: Guy was very knowledgeable. Before leaving for Tokyo, he had heard about a theatre in the suburbs where a child actor was performing. He asked to attend the play, and the Japan correspondent for Vogue Paris, Hiroko [Matsumoto-Berghauer], replied, ‘Oh, of course, Guy.’ She was very taken with Bourdin. So we attended the performance and afterwards he took a photo with the child actor along with the model [Jun Kano]. Guy had also been told the story of the statue of a dog at Shibuya station.3 The atmosphere of this series in Tokyo is somewhere between Edward Hopper and David Lynch… [Gesturing to one of the photos.] And now here we’re in Fellini’s world!

Barbara: When we arrived in a country, Guy always said, ‘I can’t start working right away like this, not without seeing the country first.’ He would buy postcards, and we’d criss-cross the country, wandering around and visiting places. Each time, it was an epic adventure, a real discovery. For five or six days, we’d set off in a van – sometimes I would drive, sometimes an assistant would. The clothes were hanging up in the back; the models already had their hair and make-up done, just in case. Sometimes we’d all be ready to go and Guy would say: ‘I’m not feeling inspired today, I don’t feel like working.’ So we didn’t work. But everything was ready to go. I loved those moments when we were just wandering around, not knowing where we were going, setting off in one direction, turning back in the other direction, in a kind of aimless drift. In Haiti, we stayed for an entire month because our suitcases didn’t arrive for the first eight days. During that time, we just travelled around the island in search of inspiration. Everyone pitched in and sometimes posed. In the photos Guy took on the Virgin Islands, for example, you can see the make-up artist Brigitte Reiss-Andersen posing in one of the pictures. She hadn’t eaten for three days to fit into the outfit. Hair stylist Raymond [Camacho] also appears. And Guy would ask me to hold the reflector, even though I had no idea about lighting. It was never right, of course, and he would yell at me and tell me I was useless. So I’d throw the reflector in his face and remind him that I was a stylist, not a photographer’s assistant. Guy and I often bickered.

‘In Venice, Guy woke us all up in the middle of the night, wanting to take a photo in the cemetery, on a bridge, in the fog, in the freezing cold.’

In reality, it was much simpler than it seems when you look at the glamour of the images.

Marie-Amélie: It was luxurious and not luxurious at the same time. We stayed in small, low-key hotels. In France, they certainly weren’t palaces. In the Pyrenees, we just ate in little bistros.

Barbara: Guy loved those little eateries, he was very down to earth.

Marie-Amélie: Yet it was also very luxurious in the sense that we had an entire week to take the photos. Time was a luxury.

Barbara: In principle, we had a fortnight to travel and cover one or two stories, roughly 12 to 14 pages. But today, when I look at the story from Los Angeles, I just think to myself: ‘I can’t believe we spent two weeks travelling to produce five pages!’

Did you ever run out of time?

Barbara: No. I was never stressed; I always knew Guy would deliver. I trusted him completely.

Martine: And time had nothing to do with money – there was no money!

Marie-Amélie: It was the school of being ‘enterprising’. We’d scout locations and he would say [imitating Bourdin]: ‘Right, let’s take a photo right here.’ And you’d be thinking to yourself: ‘He’s mad, what’s he going to do with that?’ But he’d manage to transform something banal into something extraordinary. Like paintings. He knew how to elevate a place, even when it was just some old wall. When we went to Sierra Leone – which, by the way, wasn’t particularly beautiful; I didn’t see the point in going – he found a rusty boat wreck. I thought to myself, ‘Where on earth is he taking me? He’s mad.’ I didn’t see the same thing he did. For him, it was a painting. That’s when I thought to myself: ‘He’s a real artist.’ What was extraordinary about Bourdin was that you could take him to the middle of nowhere in France and he’d manage to take a photo that was exceptional, totally unique to him, and that was completely modern for its time. The trip to the Pyrenees, with Barbara and I, was incredible. His photos from there are like paintings. He was a painter, he was a draughtsman. You could see it, he always had images and scenes in his head.

Barbara: He kept sketchbooks in which he’d draw the photos he wanted to take. He would look for locations, stop, and jot down his ideas. In Martinique, for example, he spotted an area at the foot of Mount Pelée. He wanted to set up a picnic scene there with the models [Mounia and Nahanni]. He drew the scene and I wrote down: ‘photo, picnic,’ and then I’d think about the clothes that would fit that particular image. Nothing was left to improvisation.

Marie-Amélie: I’d be thinking to myself, ‘What clothes would look best in front of this rusty boat wreck?’

Did he have a say in the choice of clothes?

Barbara: No, and I never had any problems with styling with him, although it must be said that we always went along with his ideas, except for the special ‘Fashion Collections’ issues. What Guy loved most of all was photographing swimsuits, and this idea of the Lolita, the pin-up, the doll look – those ‘Bourdin codes’.

How did you go about selecting your looks beforehand?

Marie-Amélie: Vogue had its advertisers. All the major ones, but some pretty awful ones as well, so we hired geniuses to photograph them. We had to have these star photographers in order to make each and every piece of clothing look beautiful. Some had to be given a certain ‘twist’, and to do that we had to find someone who could create the right mise-en-scène. Something awful became something completely sublime when seen by the eye of an artist. And so Vogue was really based on photography.

Did Vogue Paris allow photographers to freely express their style?

Barbara: Yes. At the time, photographers were given carte blanche. No one asked them what they were going to do. It’s nothing like today, where everything is so tightly controlled that an editorial story can look more like an advertising campaign.

Patrick: There was real magic, real passion. It was Vogue... It wasn’t ‘fashion’. What we loved most was creating images, working either with photographers we adored or those we’d discovered. We never talked about fashion… Ever! Vogue Paris was something else entirely, it was beyond fashion.

Marie-Amélie: Vogue didn’t shape my fashion sense, because I was young – about 18 or 20 years old – so I considered ‘fashion’ to be something old-fashioned. But at the same time, Vogue taught me everything from a photographic point of view, because it was seen through the eyes of great photographers, such as [Helmut] Newton and Bourdin. In Sierra Leone, it was my first ever fashion series as an editor. Well, I was more like an assistant, and they must have said, ‘Let’s give all the crap stuff to the little girl.’ But what’s incredible is that we actually said, ‘Guy will do it, because he has that eye…’. Although, to be honest, they’re not Guy’s best photos.

Did you have a clear idea of the images Bourdin was going to take?

Marie-Amélie: Yes, because with him the Polaroid was very similar to what he’d actually photograph. You knew exactly what you were going to get because he was very precise. Whereas with someone like Arthur Elgort, you wouldn’t know. That’s why I held onto Guy’s Polaroids. I still have a few of them today, because they were amazing.

‘In Haiti, we stayed for an entire month becauseour suitcases got lost for eight days. During that time, we criss-crossed the island in search of ideas.’

After so many faraway destinations for swimwear, why did you end up at the Dune du Pilat… In France?

Barbara: It was because his passport had been seized by the tax authorities. It really got to him, because he was no longer allowed to leave France. For him, this free spirit, it was terrible. So we ended up going to the Dune du Pilat. I remember one shoot where it was pouring with rain the whole time, and we ended up taking photos with umbrellas in them – the models wearing swimsuits in the rain!

Did he have any particular favourite models to take on the trips?

Barbara: Yes, some of them came a number of times, like Bridget Yorke or Nora [Ariffin].

Once you were on location, did you sometimes do street casting?

Barbara: Yes, he’d say to me [imitating Bourdin again]: ‘I need a handsome Black man.’ And I would go out and find people on the street. In Haiti, he asked Isabelle Maubert [another editor at Vogue Paris] to go find someone to place in a bed for a photo, and she came back with a leper whose arm was destroyed. That’s why he placed him on his side in the bed!

Martine: In China, it was obviously forbidden to ask girls on the street to come and pose, but I did it anyway, because I thought it was fun.

How long did the trip to China last?

Martine: Almost two weeks. In fact, we spent most of the time travelling, going from one city to another to take each photo. Formal visits and excursions were organised for us in all these places, so our actual shooting time was extremely limited and closely monitored. It was a restrictive trip, not at all suited to Guy.

Why did you go then?

Martine: In 1985, China was opening up and Jean Poniatowski, who was the director of Vogue Paris at the time [following the death of Robert Caillé, in 1981], asked me to put together a team to photograph Parisian fashion there. Guy was so excited to go to China, thinking, ‘I’m going to be the first to do this.’4 In 1985, China was in the midst of a transitional phase, and inviting us was part of their ‘opening up’ strategy. But when we arrived, we quickly realised that we were being constantly monitored by the translator and the drivers. We worked wherever we were told to, without any location scouting. The only way Guy could express himself was through having total carte blanche, so it was a complicated shoot. One day, in a public park, guards asked us to stop shooting because, according to them, the models were looking too suggestive. Guy began to get really impatient. He just felt trapped. And to make matters worse, the weather was awful: there was thick fog and torrential rain on the Great Wall. In the end, we did a lot of travelling and formal excursions for very little working time. And every time we did shoot, we were like UFOs – gawped at by crowds – which bothered Guy. He was always expecting miracles.

‘When we went to Sierra Leone, Guy found a rusty boat wreck. For him, it was like a painting. That’s when I thought to myself: ‘Bourdin’s a real artist.’’

Did miracles finally happen in China?

Martine: No, and Guy, who was extremely sensitive, felt very negative about it all. He saw a country that was in some respects opening up, but not really. We felt like we were being treated like luxury tourists, while all around us people were still wearing Mao jackets, and you’d see workshops full of children working in them. We ended up at Pierre Cardin’s Chinese premises trying to take photos the way we wanted, like in a studio, but Guy was feeling completely uninspired. And there was nothing Chinese about it! On the flight home, we were served meals in these little decorative Chinese cartons. I kept them, and in Paris we took a photo using them, which Guy was happy with. With him, we always adapted, we made do with what we had. We fed his imagination, and that’s what mattered.

How did Francine Crescent view Guy Bourdin’s on-location fashion stories?

Barbara: When we returned from a trip together, she would always greet us with, ‘So, did you have a good time? Did you eat well?’ That was all she cared about. Guy and Newton could do whatever they wanted, they were Francine’s favourites; she let them get away with anything. In fact, Guy would just hand over a single photo and that was that. He’d then spend a lot of time on the layout with Alexis Stroukoff, a little with Jocelyn Kargère, and then with Paul Wagner – all from the magazine’s art department. He would work with them on the layout before approving it.

When did you realise quite who Guy Bourdin was? When did you understand his world?

Marie-Amélie: I understood by working with him and getting to know him. You could tell that he was a true artist. He drew what he wanted to photograph. So there was a real artistic side to his work.

Martine: He did a lot of paintings, some of which featured elements that we later saw in his photographs. But he wasn’t a great painter, whereas he was a great photographer.

Barbara: Guy hated the idea of being a photographer. He wanted to be a painter. For him, anyone could be a photographer – it wasn’t a real job.

What’s your recollection of the end?

Marie-Amélie: Towards the end, he had less support around him and had let himself go a bit. Times had changed, and his work was also of lower quality, to be honest.

Barbara: It was while in Haiti that his cancer was diagnosed, and the worst thing is that he never sought treatment. He didn’t feel well in Haiti; he often lay down in the shade of the truck because he had stomach pains. And when we got back, we discovered he had cancer.

‘When the tax authorities seized his passport it really got to him. He was no longer allowed to leave France. For him, this free spirit, it was terrible.’

Post scriptum: By the mid-1980s, Guy Bourdin had begun to decline. Constantly harassed by the tax authorities, devastated in his private life and suffering from stomach cancer, he was forced to end his prolific 33-year collaboration with Vogue Paris following Francine Crescent’s 1987 departure from the magazine – his lifelong champion and eternal protector. His very last international trip for the magazine took him to Marbella and was published in August 1987, while his final editorial story, entitled Le cinéma des robes-maillots (‘The Cinema of Swimsuits’), appeared in the June-July 1988 issue. Francine continued to employ him for her new magazine venture, The Best, but his heart was no longer in it. Guy Bourdin died of cancer on 29 March 1991. He was 62 years old.