Interview by Mirjam Kooiman

‘I collect elements that fascinate me: glass orbs or masks, for instance. I keep them with me. And then, when we’re on set, even if the client says, ‘We’ve got the shot,’ I’ll push for one more, and throw in that mask or orb. Those are often the images that make the whole thing sing. I think that subconscious side is a desire to escape reality, to tap into a dream logic, a surreal edge. To create something that doesn’t exist yet. Because everything already exists in our image-saturated world.’

Anyone who entered Foam – Amsterdam’s photography museum – between October 2023 and January 2024, was stepping directly into the dream realm of Carlijn Jacobs. The floor mirrored the images on the walls, echoing the atmosphere of disorientation: a face projected onto another face, an eye gazing at you from inside an open mouth. But the first image one was confronted with upon entering her exhibition was of a woman’s body appearing to sink into a bed. Her torso cinched beneath a crimson, vaulted harness, her face hidden behind a white mask from which a scarlet glow spilled out across her skin. The fiery red light bled into the wall, reflecting from behind the print itself – as though the dream had slipped past its frame.

Sleeping Beauty, the exhibition was called. But this was no fairytale princess lost in eternal slumber – rather, a meditation on how modern technologies lull us into sleep, away from a reality that’s increasingly difficult to grasp. Or perhaps a reflection on how they allow us to dream new worlds into being, to bend reality to our own design.

Carlijn Jacobs has never shied away from technology – neither today, nor when she first picked up a camera at the age of 13. I witnessed this firsthand during the curatorial process for her exhibition at Foam [Kooiman is the museum’s head of artistic programming and curator of the Sleeping Beauty exhibition], as we moved through hundreds of images she’d created over the years. In between edits, she showed me how she’d recently been experimenting with tools like DALL·E and Midjourney, feeding them her own photographs to see what new, dreamlike compositions might emerge. For Jacobs, AI wasn’t a disruption – it was an extension. Not a replacement for the photographer’s eye, but a counterpart to it.

Her exhibition marked a first for Foam: it included AI-generated imagery, displayed not as novelty, but as a natural continuation of photography’s evolution. Photography has always been technological – from chemical processes to digital sensors – and with AI, we see a shift not in the essence of photography, but in its method. These works remain photographic, though the camera is now the point of departure, and no longer the final act. The photograph becomes material, the apparatus dissolves into code.

It’s this very tension – between the mechanical and the mythical, the constructed and the instinctive – that has come to define Jacobs’ vision as an image-maker. Her rise in the fashion world has been no accident. Long before she was shaping visual mythologies for brands such as Chanel, Louis Vuitton, Mugler, Balenciaga and Loewe, and for the likes of Beyoncé and Kim Kardashian, she was a child fascinated by the invisible systems behind the visible world – a mind wired to understand how things worked, moved and responded.

From early experiments designing her own imaginary fashion magazine covers, to capturing Amsterdam’s nightlife, and eventually relocating to Paris to build universes of her own, Jacobs has always worked in pursuit of a personal mythology. Her references are layered: Venetian masks, geishas, latex, gloss, distortion, glamour and above all, camp. Not as empty kitsch, but as performance with intent. Her work is more than aesthetic, it’s the subconscious made tactile, the dream rendered wearable, the mask worn not to conceal, but to transform.

Mirjam Kooiman: Can we start at the very beginning? We were both born in the early 1990s, so we still remember life before smartphones. But we also grew up during a visual culture explosion, with all the platforms appearing on which to share images. What were you into back then? What shaped you?

Carlijn Jacobs: Oh, I was completely obsessed. I remember Hyves [a Dutch precursor to Facebook] – you could actually code your own page. I got really good at it. I had flickery backgrounds, pink poodles, new layouts every week. I was heavily immersed in all the visual stuff I could find. And MySpace – I loved styling my page, curating my little online world. That was everything to me.

So MySpace really felt like your space?

Exactly. I loved being able to design it, decorate it. Hyves was even better in a way, because you could customise it with HTML. MySpace was more limited. But yes, I got into the technical side of it too – no fear there. I’d play around with

the code to make everything more ‘me’.

So you were immediately into the technical stuff – that didn’t hold you back?

When I was 14, my sister’s boyfriend at the time – who was from Nijmegen, the big city compared to my tiny village Groeningen – showed me Photoshop for the first time. I remember sitting behind him, totally in awe. I asked him to make fire effects! It just clicked. From that moment, I started experimenting with it myself.

Did you already have a camera then?

Yes, I had one when I was very young. My best friend lived a few villages away; we used to hitchhike to each other’s houses. She was into sewing clothes, her aunt was a seamstress. So we’d do these photoshoots in barns, on haylofts. I’d photograph her in the clothes she made, and then I’d edit the images in Photoshop – putting her into different environments. It was our way of escaping the village. And I’m sure America’s Next Top Model had something to do with it too. I remember seeing beautiful editorials in magazines and just wanting to disappear into that world.

‘When I was 14, my sister’s boyfriend showed me Photoshop. I remember being totally in awe. I asked him to make fire effects! It just clicked.’

Was it always clear to you that you wanted to be behind the camera, not in front of it?

Oh yes, definitely. I tried being in front of it, but it just didn’t work. I needed to make the image. I remember we even filmed a Pokémon video – we dressed up, jumped on trampolines, and I edited the whole thing. At the end of the YouTube clip, it says ‘Camera by Carlijn Jacobs’. We were, like, 13. [Laughs]

Is it still online?

Yes… And it’s really bad.

That video alone says so much. Escapism, world-building, early Photoshop. You mentioned that small-town feeling, where you basically had to invent everything yourself. I think that’s also something about growing up in the Netherlands. On one hand, we could say that living below sea level, the Dutch are quite inventive. On the other hand, there’s that typical Dutch pragmatism. How do you think Dutch culture shaped you – or did you perhaps react against it?

I think it’s both. I love extravagance, but I’m also very grounded. That contrast is very Dutch, I guess. Also, we’re a privileged country: I could think about going to art school because I lived in a society where that was possible. I remember thinking, ‘I’ll probably never have a real job – but fuck it, this is fun.’

Did your parents support that mindset?

They gave me a lot of freedom, in a very supportive way. They didn’t push me, but they didn’t block anything either. The funny thing is, I didn’t even know art school was an option. It wasn’t on my radar. I didn’t see myself as ‘creative’ – my sister could draw, sing, all that. I didn’t think I fit the label.

You were making edited video clips at the age of 13 and didn’t see yourself as creative?

[Laughs] Exactly. But in my world, the only ‘photographer’ was the person who took your passport photo. I didn’t know creative jobs existed. If you grew up in Amsterdam, maybe you knew someone who was an art director or a stylist. Where I was, that just wasn’t a thing.

So how did you end up pursuing photography?

I went to the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam and started a course in Lifestyle & Design, which was perfect for people who were creative but didn’t yet know in what direction to channel it. Then, in my second year, I took my first photography class. The teacher immediately said, ‘This is your thing.’ I started getting top grades. I even went to the studio manager and asked if I should switch to the photography department. He told me, ‘No, you already know what you want to shoot. Focus on your ideas. You’ll learn the technique.’ That advice stayed with me.

It sounds like that broad creative background ended up working in your favour.

Yes, absolutely. I always still think in terms of the whole picture – graphic design, layout, research, concept. It all feeds into the work.

So was it clear from the beginning that fashion photography would be your main focus?

Not exactly. At the time, it was more a feeling of ‘I just want to make images.’ That’s what it came down to. So I was still photographing weird stuff, like a pig’s trotter, I remember. It was all still a bit offbeat. But I guess if you’re naturally drawn to fashion, it becomes a logical next step. And of course at some point I also had to make some money. I was posting little visuals on Facebook. And at some point, it started rolling. People saying, ‘Hey, we need someone.’ That led me into party photography.

That’s where it really took off for you?

Not at all. But it’s actually a funny story. I was on Facebook and I don’t know if you remember them – the Fotomeisjes [The Photo Girls]. I had this classmate from art school who asked me, ‘Do you know a photographer who could shoot at Club NYX tonight?’ And I thought: ‘I’ll do it. That has to be me.’ So I went to Club NYX and started shooting there. And that’s how I got scouted by the Fotomeisjes, who were shooting every week at Chicago Social Club in Amsterdam. They were kind of referencing the Cobrasnake scene in LA – you know, capturing cool girls like Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen in clubs. So yes, it already had a fashion lens to it. Observing the crowd, spotting who looked good. Anyway, they asked me, ‘Can you shoot all summer at Chicago Social?’ I thought, obviously yes. And that’s how I met Imruh [Asha, stylist].

Really? How did that happen?

I was photographing and Imruh just kept showing up in front of my lens. I was like, who is this guy? Coincidentally, that same night I was working on a piece for i-D Netherlands – portraits of people in nightlife. I told him I had to run to this club, and he said, ‘I’ve got a scooter. I’ll drop you off.’ That’s how we met. He was working at SPRMRKT at the time, the concept store by Nelleke Strijkers and Annika Beekmans at the Rozengracht in Amsterdam. First he interned there, then started working. They had beautiful designer pieces – Margiela, all of that. I was about to graduate, and he said, ‘We can shoot in the store after hours.’ So that’s how we started doing editorials. Just like that. It was all very playful.

So these opportunities just kept coming, each one leading to the next.

Yes, exactly. It all felt quite natural.

‘I didn’t see myself as ‘creative’. I didn’t even know creative jobs existed. The only ‘photographer’ I knew was the person who took your passport photo.’

Did you ever think about it the other way around? You know, strategically? Like, ‘What’s the next move?’ Or was it mostly intuitive?

Pretty much all intuitive. That’s how I work. But I think once I realised ‘OK, I want to become a photographer,’ I started being more conscious about it. Someone recently reminded me that back in my second year I said, ‘I want to be a big international fashion photographer.’ And I was like – ugh, kind of cringe. But yes, I said that. I guess it shows there was already intention behind it, even then.

Do you think anything from your early life shaped how you see or capture things now?

Maybe my taste – it’s always been quite intuitive, and it hasn’t really changed. Like, I remember this pink poodle I had on my Hyves page. Very random, very visual. But it made sense to me. That kind of image made sense in my head. I also remember the first time we got the internet at home, and I came across Miles Aldridge’s website. His photos were strange. Cigarettes being stubbed out on eggs, that kind of thing. I was obsessed. That was the first time I felt, ‘OK, this is it.’ Then I saw the images he shot of Kristen McMenamy, his muse. All these nudes. She looked like a ghost. That darker side of fashion, that whole world, it really stuck with me. And then, last year I was working with her in New York. I told her how into those images I was. She just said, ‘Oh yes, those were done by my ex.’ I thought: ‘What is this full-circle moment I’m in right now?’ Surreal. But also kind of funny.

What would you consider your first real ‘work’? Even if it didn’t feel that way at the time. Looking back, what marks the start? Was it the Pokémon video?

No, that one’s insane. That absolutely doesn’t count. The thing is, as an artist you’re never really satisfied. That whole early period where I was already making a lot of work, I now see as playtime. I started so young. But if I really had to name a first serious piece, it might be that Vogue Italia shoot. The one with the fishbowl. There’s probably earlier work that was already making sense to me, but that one became a print, it sold well, and I felt like, ‘OK, this is official now’. Of course, I was still figuring things out. You learn from every shoot. But in hindsight, that shoot felt like a first real mark.

Did something click for you, personally, with that moment?

Yes. I had just moved to Paris, and it’s hard to break into the scene. You’re sending all these emails, getting no replies, trying everything. I didn’t have international representation, only in the Netherlands. So people didn’t really take me seriously. I was young, a woman, handling major financial negotiations with big clients. It was a lot. But I’m grateful for that time, actually. I handled all my own budgets, all the negotiations. You learn so much. Still, at some point I really wanted an agent. And then, all of a sudden, I started getting emails from agencies. That’s when I thought, ‘OK, this is happening.’

Was that linked to a specific shoot?

It was just before the Vogue Italia one. But there were a few things that landed around that time. I got a message from [stylist] Charlotte Collet asking if I could shoot a story for M Le Magazine du Monde the following week. It was fast. Someone probably dropped out. But I happened to be there. We shot the story together and it ended up as three covers. It was a jewellery story, but very artistic. One of the images was that Indian man’s hand – do you remember?

Yes, like the one with the fishbowl, it was part of your exhibition at Foam. That image really stuck with me.

A week later, I got a call asking if I wanted to shoot the Vogue Paris cover. Back when it was still called Vogue Paris, not Vogue France. It felt super exclusive at the time, and very few women were shooting those covers. I got a message from Emmanuelle Alt. That’s when it really started rolling. That was the moment I felt like: ‘I’m entering the Parisian scene.’

And you and Imruh had just… decided to go to Paris?

Yes. Totally. We thought, ‘If we want to make it, we need to go where it’s happening.’ In the Netherlands, I wasn’t getting booked by commercial clients. My work didn’t really fit. In the Dutch market, it’s mostly Nike, Calvin Klein… They weren’t calling me. By that time, I was creating my own imaginary fashion magazine covers. And for Imruh too, whenever he needed to borrow clothes for styling they always came from Paris. So at some point we just said, ‘Let’s go.’ We kept our place in Amsterdam, but we went. No real plan. Just the decision to go.

When was this again?

About seven years ago now. Time flies.

I’m just trying to imagine how your whole visual brain came together. Because I was just thinking back… You know, our first meeting was actually around the time of the Helmut Newton retrospective exhibition at Foam in 2016. We included your work there as part of a new generation, a kind of visual continuation of his legacy. Could you describe again how Newton influenced you?

Well… He portrayed women in a very powerful way. Never soft, always strong. That’s something I do too. I wouldn’t quickly photograph someone dreamily lying in a flower field. I like it when there’s a touch of masculinity there. Newton had that too, this masculine edge. That’s what I love about his work. Even though it was shot by a man – and yes, it can be quite sexualised at times – I still find it incredibly empowering. The woman isn’t objectified. She’s exalted. He puts her on a pedestal. I find that very beautiful. And so I try to do that in my own work as well. That sense of elevation. But I also really admire the analogue feel of his photography. The colours, and especially the odd details.

The odd elements set his work apart.

Exactly. There are so many images out there. But it’s that one strange thing, that unexpected detail, that makes it stand out. He was brilliant at that. Especially at that time. I think people had more freedom then, too. Things weren’t as restricted. That’s something I do struggle with now.

You do? Can you say more about that? Because yes, times have changed. And Newton’s work, for example, is now viewed through a very different lens. But how do you experience that shift? What’s changed for you in the landscape you work in now?

Well, I’ve only ever worked in this era. I’ve been doing this for about 10 years now. But what I really notice is how much the whole world has changed. There’s just so much content now. Fashion has become this massive machine. So many clothes. So many images. Which means there’s an enormous need for content, constantly. That whole fast pace of photography, that’s completely different from the past. Now, you have to shoot a minimum of 15 images a day. Back then, they probably had a week for the same thing. There’s just no time to experiment anymore. No one has time.

‘People didn’t really take me seriously. I was young, a woman, handling major financial negotiations andbudgets with big clients by myself. It was a lot.’

I definitely want to come back to that later. I kept following your work and later invited you to do a solo show at Foam, Sleeping Beauty, which happened in 2023. And what struck me there was the way the exhibition started with darkness and that mirrored floor – it really made me see how much of your work is tied to the subconscious. So I’m still curious: how do you translate the subconscious into conscious choices in your work? Because I can clearly feel its influence. But at the same time, you work in a context where things have to be deliberate, collaborative, considered.

I think I just collect elements that fascinate me. And they can be wildly different, like glass orbs or masks, for instance. I keep them with me. And then, when we’re on set, even if the client says, ‘We got the shot,’ I’ll push for one more, and throw in that mask or orb. And honestly, those are often the images that make the whole thing sing. So yes, that subconscious side… I think it’s tied to a desire to escape reality. To create something that doesn’t exist yet. Because everything already exists, especially in our image-saturated world. I’m always chasing something that feels like me but that also taps into that dream logic, that surreal edge. That’s the subconscious I try to access.

Given how high the pressure is, and how fast you have to work, do you have any rituals or ways to reconnect with that other world?

Definitely. And I think it’s more important than ever to carve out that space. It’s so easy to be pulled in different directions – you’re working with teams, advertisers, you have to hit certain marks. Even if you’re working for a magazine and technically have creative freedom, there are always limitations. Maybe a look has to be included. But maybe I didn’t want clothes at all – maybe I wanted them naked. But that’s not allowed. So what I’ve learned is that the only way for me to protect that space is to prepare obsessively. I plan everything. I write down all my ideas ahead of time. I map out the day, scene by scene, beat by beat. There’s no room for improvisation anymore. No time. So I’ve become extremely organised, almost militant.

Even under pressure like that, where do your ideas come from?

Lately, it’s been a challenge. I’ve had so many projects going at once. But I’ve just had a summer break and suddenly I’m brimming with ideas again. It made me realise how important it is to step away sometimes. Rest really is fuel for creativity. But yes, I do a lot of research. I have a whole archive. I collect references constantly – films, objects, visuals. Anything that sparks something. I save it all on my phone. I have folders for everything. So, let’s say I get asked to shoot someone like Nicole Kidman – I just shot her for American Vogue, which is coming out soon – then I dive into my folders and go nuts. But even then, there are so many layers. Her management needs to approve it. The stylist, the editor… It’s a whole chain. So I’ll often prep three full concepts. With moodboards. With studies. Just to get one through. Fashion is like a puzzle. You’re constantly solving things, adapting. But that also keeps it fun.

What are your biggest sources of inspiration?

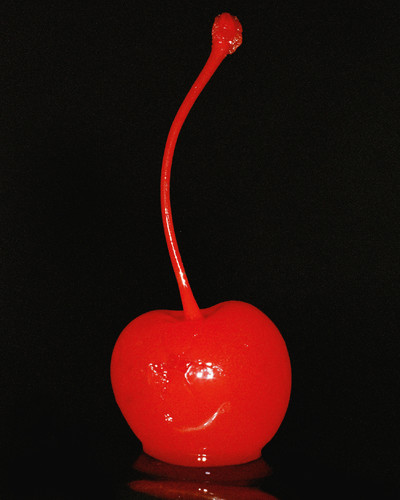

Honestly, it’s super broad. When I travel, I’m constantly seeing things, like stained glass windows, for example. I’ll think, ‘This would be amazing for a set.’ I’m obsessed with how light moves through space. And I just love images, full stop. There are so many photographers I admire, and they’re all so different. From Bruno Barbey to David LaChapelle. I’m drawn to artists with very distinct visual styles. I also have a lot of Japanese influences in my work. And I collect objects, especially animals. Animals appear in so many of my shoots. Also food. Especially food in impossible colours. I’m obsessed with that. It’s a sensory world I’m constantly building in my head.

That Japanese influence was also clearly visible in your exhibition. What is it about Japanese culture that speaks to you?

I think it’s the purity, the minimalism – of course that’s part of it – but actually, I find Japanese theatre incredibly inspiring. It’s so focused on costume and transformation, and it feels so far removed from my own world. That distance is part of what draws me to it. It’s that same longing for something I didn’t grow up with.

I’m just trying to sketch out your frame of reference a little more. I also read somewhere that you once rewrote Notes on “Camp” by Susan Sontag. What does camp mean to you?

I immediately think of the Eurovision Song Contest. My graduation work was kind of referencing that, actually. I started noticing that the things I liked, my intuitive taste, wasn’t necessarily seen as ‘chic’ by everyone. And I found that tension really interesting. So I started diving into camp: the culture of borrowing from other styles, celebrating what’s considered low-brow or kitsch. Like how Balenciaga works with Crocs now. Eurovision had that too: the elite dismissed it but still watched it. That play with cultural layers really stuck with me. It’s definitely part of my work.

How do you relate to ideas of chic versus vulgar?

It’s a fine line, and a tricky one. Back when I graduated, I did this shoot that almost looked like a Eurovision scene – a model with glitter, that whole vibe. It was years ago but that energy still lingers in what I do. I don’t think in terms of ‘chic’ or ‘tacky’. I think in terms of what triggers nostalgia for me.

‘The things I liked weren’t seen as ‘chic’ by everyone. So I started diving into camp: the culture of celebrating what’s considered low-brow or kitsch.’

Your work often references the 1980s, sometimes the 1970s too, but at the same time there’s also a strong sense of the futuristic. Almost like a version of the future imagined in the 1990s. How do you see your work in relation to time or zeitgeist?

Every era has something beautiful. If something inspires me, I’ll borrow from it. I’m definitely more drawn to the 1980s than to, say, the past 10 years. Maybe because I lived through the recent stuff, so it feels too familiar.

And although you didn’t live through the 1980s, you certainly seem nostalgic for that era.

Exactly. It’s like I skip the in-between parts. What ends up in my work is a sort of mix of history and future combined.

Is there something specific about the 1980s aesthetic that attracts you?

It’s hard to say. I think someone mentioned the 1980s in an old interview with me and ever since that reference keeps resurfacing. But it is something that returns in my work. I love the way power is visualised in the fashion imagery of that era – Newton’s women, the shoulder pads, that strong silhouette.

There’s something really commanding about it.

Would you say you’re exploring how women are portrayed? Or am I reading too much into that from a feminist angle?

I wouldn’t necessarily call it feminist, but I am drawn to visualising women. Not that I don’t enjoy photographing men, but with women transformation feels more accepted. There’s more room to dress them up, to change them, to play with identity. That showmanship, that sense of becoming someone else, that interests me. I’m not looking for someone’s true self; I’m looking for the performance. That’s why I work more with women, or even with mannequins – anything that can be reshaped.

That connects back to the Japanese references again: the geisha, the mask, the masquerade you mentioned earlier. I wanted to ask more about your process. How do you navigate the aesthetic of a client, especially when placing someone else’s creation within your own visual language?

That’s one of the trickier elements of fashion photography. Especially at the beginning of a project. But I make sure I’m really involved from the start: I’ll respond to a brief with a moodboard and gradually start steering it in my direction. In the beginning, it was a bit of a battle – I was like a tiger, trying to protect my taste. But now I’m lucky and clients usually come to me for a reason. Though occasionally I still think, ‘Why did they book me for this?’ But generally, I make sure I’m surrounded by people I trust – my stylist, my hair and make-up team – because they know my eye. That way, even if 50% of the concept comes from the client, the other half is mine, and it still feels like my world.

‘I’m looking for the performance, not someone’s true self. That’s why I work more with women, or even with mannequins – anything that can be reshaped.’

Have you ever surprised a client to the point where they saw their own product differently?

Well, kind of. I once did a campaign for Byredo, for their make-up line. They wanted to shoot in a library – old books, and with a kind of dusty, golden atmosphere. I couldn’t quite settle for that; I wanted to see what would happen if we took it a bit further. I suggested photographing the model first, printing her portrait onto a book cover, and having the model then hold the book in front of her face, creating a surreal, slightly warped effect. They were unsure at first, but we went for it, and the resulting images became the campaign. Sometimes, stepping outside the initial idea leads to something memorable.

Maybe you get tired of being asked this question – feel free to say so – but I saw that in 2024, The New York Times Style Magazine curated a list of 25 photographs that define our modern era, and your photo of Beyoncé’s [Renaissance] album cover was on it. I thought that was amazing. At the same time, I read that you weren’t really given much direction for it. What can you tell me about that shoot?

When I first got the request I honestly didn’t realise it was going to be such a big deal. I even thought, ‘Wow, haven’t heard from Beyoncé in a while… Is she still going?’ Once I got to LA, the production side of things was different; the music industry operates differently from fashion. You have to be prepared for everything – pre-lighting, multiple sets – because you don’t know if you’ll get one minute, 10 minutes, or an hour. You have to be ready with every idea. In the end, the shoot kept getting extended; it just took longer than expected. You work with a creative director who has a vision, and you try to bring your own perspective. But ultimately, you’re working with a superstar who has the final say. When the album came out, I suddenly got calls from everyone. I really hadn’t realised it would blow up like that. In hindsight, it was funny, and really cool. But when I look at the other images on that [New York Times] list, like Cindy Sherman’s, which are more personal and iconic, mine feels a bit different. It’s a commercial image, made for someone else.

Is there a photo – maybe one of your own – that you feel should have been on that list instead?

The one that feels most personal to me is the geisha photograph that was exhibited at Foam. Years ago, I was walking down the street in Kyoto in the evening when a taxi suddenly stopped – a real Japanese taxi with lace curtains – and a geisha peeked out and stepped onto the street. She walked quickly on her wooden slippers to wherever she needed to go. That moment stayed with me; it felt like a dream. Years later, I recreated the scene in Kyoto, and that became the photograph.

Your show at Foam also marked the first time that we, as a photography museum, had exhibited AI-generated images. You were one of the first within the photography scene to see AI not as a threat, but as a creative collaborator. How do you feel about that now?

Still the same. I talk to ChatGPT every day – I’m addicted. I’ve learned so much from it. AI is definitely an addition, and the world is changing fast. I was recently called about the Guess campaign using AI-generated models – there was a lot of discussion. I have mixed feelings. On one hand, yes, there are concerns about representation and standards. But I’m not against AI. Photoshop was manipulation too. It’s different, sure, but it opens up new possibilities. Manipulation has always been part of photography, ever since the invention of the dark room.

I’ve noticed younger generations at art schools returning to analogue photography, as if they’re seeking grounding. You, on the other hand, embraced AI early on. What do you think this says about our time?

Analogue has been a trend for a while, especially in fashion photography. It allows for experimentation. Light leaks or other imperfections create beauty. It’s also a great way to really learn photography. Film just looks better than digital. But analogue and digital don’t feel opposed in my work. Digital allows precision, analogue allows imperfection. Both have their own challenges and artistry.

‘I map out the day obsessively, scene by scene, beat by beat. There’s no room for improvisation anymore. No time. I’ve become so organised, almost militant.’

Are you never worried that AI might replace your work – like clients generating campaigns without a photographer? If your work ever became obsolete, what would you do?

I have thought about that, and I think it’s smart to have a backup plan, but I doubt AI will replace everything. Perhaps product photography will be the first thing affected. For bigger campaigns, people still want to see a human face. I’m not too worried, but I do consider it. You can’t cling to the past. And, in any case, I’d find something else to do. There are so many things I love. I’d love to run a dog kennel. Or – and this might seem a bit silly – I’ve always dreamed of working with dolphins. I love animals and active work. Something hands-on, something real.

So it’s about seeking new experiences?

Yes, exactly. The more worlds you experience, the better. That’s why travel is so important to me – because it broadens your understanding. And fortunately my work allows me to do that.

Where do you see fashion photography heading in the next 10 years?

I do worry about the overkill of images. There’s just so much imagery being produced now. And, of course, I do really hope we return to quality over quantity – taking the time to make something special, rather than always producing fast and cheap. I hope it moves closer to the 1980s approach, going somewhere like the Bahamas and making magic with time and care.

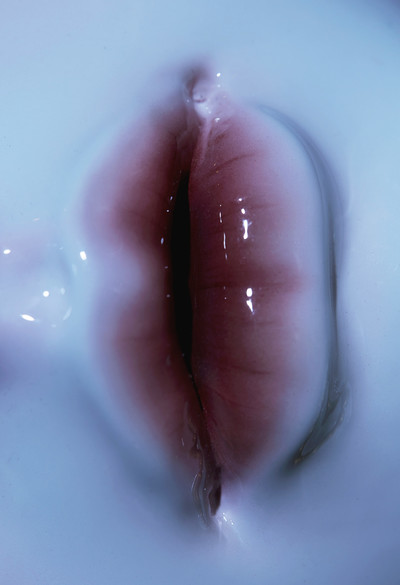

Cover Girls, Series 1.

Amsterdam, 2018.