Interview by Mathias Augustyniak

‘A teacher warned me not to look for the meaning of life in a pop song. My answer to him was: ‘That’s all I’ve ever done.’ And it’s all I’ll ever want to do. I was lucky to find a medium to explore that when I was 17 – and I think it probably saved my life.’

Since the early 1990s, when his first editorials began to appear in i-D and The Face, David Sims has been ceaselessly redefining what it means to be a fashion photographer. Favouring style over fashion, his images consistently challenge convention – always to striking effect. His restless pursuit of the new has secured his place among the medium’s greats. Here, he speaks with his friend and long-time collaborator, the art director and M/M (Paris) co-founder Mathias Augustyniak, about the art and craft of image-making, and what continues to drive his work today.

Mathias Augustyniak: We’ve been trying to do this for God knows how long. I would say two months now.

David Sims: It’s either a reflection of our ineptitude, our inability to be organised, or maybe we’re just very busy people.

Since I’ve known you, I’ve never felt like you have been resting. You’ve been constantly engaging in a conversation with your surroundings. Sometimes you disappear, which happens to all of us, but I always hear from you – of course, when we talk, but also through your work.

Would you say what appears to be restlessness is also kind of charged? That I make things visible somewhat – to you anyway. Is that what you mean?

What I mean is that I see you as someone who has a point of view. And you keep engaging in a conversation not just to express yourself, but to express your understanding of the world.

I think there’s a degree of clarity that I get with that question. As a kid, the things that were normal for most people seemed alien to me. So I got in people’s ways simply by asking how and why. Quite early on, you realise that most of what that results in is other people’s frustrations, right? I think a lot of children go through that. But when given a medium, you can attach that side of yourself to what people like to call a ‘practice’. But it’s torment as well. It’s got to be the same for you. I don’t think I’m speaking in terms which are foreign to you.

At one point in my life, I declared myself an artist, even if I operate in the graphic design world – I design typography, I make books, I do exhibitions. I’ve never heard you declare yourself an artist, but you still express yourself through your work. I always see a comment about the world. I hear you within your work. Do you consider yourself an auteur?

I have a grasp of what an auteur is or does, but whether I think of myself in that way, I would say no. But I’m interested in the question. Let’s say that there’s a certain level of nervousness around your ideas or impulses, and you don’t quite know what they are when they’re in the process of manifesting… Sometimes, when I look back on the work, or on a particular picture, suddenly the message or the idea becomes more readily available to me on an emotional level. I kind of go, ‘Oh, fuck. Right, yeah.’ Without wanting to make it sound a bit trivial, I suddenly realise the importance of the way that I felt when I photographed the image, and I was only able to connect to that because it had turned into a riddle – one that unravels and eventually becomes apparent to me. Those are the pictures I end up wanting to claim and want to live side by side with, even if they don’t speak to anyone else. The subjective nature of those pictures and the way that I feel about them in the end is so obscure, and in some cases a bit absurd, that I couldn’t imagine someone else getting it. There’s a failure to that image if it’s taken in order to communicate something. Most of it is wanting connection and to find out who else out there might get it, but I don’t rely on that. I don’t assume it. I don’t know if that means that I’m one thing or another to you. And if it falls into the description of an auteur, I don’t think I can have any genuine authority over that.

‘If you were brought up as a working-class kid the way I was, you weren’t told to have aspirations. What you had was your rebelliousness.’

I was expecting you to answer like this. I know you, though, and this is why I’m putting you in the category of an auteur. For me, you’ve kept doing the exact same thing. I remember meeting you in 1996 and you had a box of Polaroids, which was basically your portfolio. I found it extremely courageous and bold to say, ‘All my work is in that box.’ It was several types of images and they were all different but all had a link. There was one still life photograph of a watermelon. There was one black-and-white fashion image, and then there was the same watermelon on top of it. So there were two images of the watermelon. One was complete and then the other one was crushed in. You had dug a hole in it. It is still the same toolbox you use today. Does that resonate with you?

I think you’re right. What was in that box was an opportunity for me to not have to say anything. There were a multitude of proposals in there, but ostensibly that occurred in that particular moment because of some restlessness, and because of the way in which I experience images through all sorts of channels. I don’t consider photography to be defined by one kind of ritual or rigorous practice. I’m more curious about the idea of a high and low version of the craft or the art. One of the things that inspired a second wind of wanting to make pictures was having found a box full of images from my cousin’s bedroom from when we were kids. I think the reason that struck me was because I wanted some emotion to be available to people in my pictures. But I never really feel like it gets there. And these pictures that I discovered in my cousin’s shoebox – literally under his bed, it’s that clichéd – they were very unsophisticated pictures, but they were full of emotion. They were collected memories, people who had gone, people who are no longer around. Of course, that creates emotional resonance. But I’ve never wanted to practice just one version of the craft.

It was a time when a lot of technicality went into the taking of a picture because there were no digital processes to add anything to pictures, but there were printing techniques that would give a certain quality to the photograph. Your pictures were always very simply printed, but extremely well executed. Somehow in this looseness, there was a sense of perfection.

There is a craft to photography. When we worked in an age when really all we had were the simple tools that analogue afforded us, to some degree we had to manipulate the ingredients in order to give the image singularity. There were as many keen enthusiasts or amateurs as there were professionals, and we were all given the same tools, depending on your budget, right? But the further you went into the principal stages of a photograph, the more you could stretch and explore the limits of each stage. Lighting for me in particular. When I saw what Arnold Newman had done to Alfred Krupp simply through lighting, and how unsettling that portrait was, it drew me to the power of light, tone and contrast. Those tools were available to me from the outset, and that’s what made them compelling. I remember you talked to me once about my colour codes, and I was very flattered by that. When you said that you’d had some kind of response to them, that was simply enough to push me forward. I don’t know if you can do that anymore – if you can create colour combinations and expect people to feel disturbed or disrupted by them, the way that that Larkspur blue background did in the 1990s, because it was viewed as something fairly banal and unattractive. But that background, for a long time, did enough to gain people’s attention. A lot of people didn’t like it, and that was as interesting to me as anyone that did.

I had a conversation with Glen Luchford and he mentioned that you were an extremely good colourist, and I completely agree. You mentioned that you started that trend of using a colour as a background which could have a meaning. But also the way you lit it made a difference.

Becoming successful put me too near the edge of failure. And in order to kind of unconsciously survive that, I started to imagine ways in which I could put people off my work. These ideas that people had about what I’d made up to that point felt so inaccurate that I wanted to test people. That’s where the primordial therapy shit comes in, really. Maybe I was saying, ‘But am I as good as you think?’ Because it was a shock to have success, right? It wasn’t expected. So, what I did was pretend that I was nothing but a keen amateur. And what could be more amateur than this awful blue paper background?

This is where I go back to the question around the notion of auteurship. At one point it feels like you want to know if people are still listening to you. So, there is a need for provocation. Like, ‘OK this blue is a completely unexpected blue. Are you still following me? Do you still like my pictures?’

If I remember accurately, up until then I’d done everything in black and white, everything in daylight. And then I went for the opposite, which was overlit, in colour against colour. Kind of colour comparisons, like a colour conflict. In a way, it was perverse, but it was a test of whether I had any value at all. Because when you get trendy, which is what me and a few others had become, it’s destabilising. I don’t want to be part of a group. I don’t want to be seen as a trend. I just want to have an opportunity to continue.

In your work I see longevity, I see a trajectory rather than a beginning, middle and end. What’s interesting is that you keep evolving. There is this kind of restlessness, a lust for life. I think your relationship with Guido [Palau] is very important. I know you are good friends, but at one point you were crafting images together where you knew that a piece of hair was also a way to express a feeling or an idea.

The culture that Guido and I both grew up in, our exposure to ‘high’ culture was pretty limited. We grew up in a period of accelerated pop culture in the UK, but things were still very small. In Squaring the Circle [a 2022 documentary film about music album art design studio Hipgnosis], Noel Gallagher very succinctly says that for a long time someone’s record collection was akin to an art collection in some aristocratic estate. The kind of ideas that went into creating album art, purely in terms of design, style, photography, was a source of utter fascination for a lot of people my age. I’m glad that I was able to learn through that particular channel, because it went with this incredible musical soundtrack. There’s this kind of liminal experience that you have because you’re confused and drawn to the picture. You’re informed by it, you become emotional about it, and then the music does a whole other thing for you. It fits into the rest of what is left on the scale of your emotions. It can literally make you a different person. When I discovered The Stooges, I thought I was the only person on the planet who had heard them. Of course, I wasn’t, but I felt like that, and the fabric of my life completely disintegrated in front of me, and it became something else altogether, which made me a passionate person. Working with Guido, there was a language between the two of us because I knew he felt the same. We are completely different people, but we strove towards the same thing. For us, hair individuates people in our culture – from the 1970s through to the 1980s, we expressed ourselves through hair. We couldn’t afford clothes, but you could hack away at your hair over a basin in your bathroom with a pair of scissors and put colour in it without having to spend much money at all. It was amazing how powerful that tool was.

It upset your parents, and it would get you expelled from school. You could literally get kicked out of school for dyeing your hair. It was like a political statement. It was people just reaching for the resources that they had. You were only a punk if you meant it. And if you meant it, you had to pay the price. When I got to London and saw what the queer community was doing – how they dressed up and how they were presenting themselves to a very staid and conservative country – it drove that fascination even more, because those people started to appear in style magazines alongside musicians. It’s not to say that London was the first place where that had happened, it had been going on presumably in countless different cities for countless different decades, but that was what was in front of me.

‘We couldn’t afford clothes, but you could hack away at your hair with a pair of scissors and put colour in it without having to spend much money.’

I think you were the first to really deal with communicating the core expression of a human being, respecting every part of them. I’m interested, how do you express someone’s inner self? This is what you did in a very natural and delicate way.

We were wanting to create something that was, for us, novel. Knowing full well that novelty wouldn’t get us very far at all. We were still in a rebellious phase, let’s say. We struggled in adolescence, we’d been given this platform, and I don’t think we’d grown up quite enough to listen to criticism. We just went forward because we didn’t have anything to lose. The idea of profit, aside from getting respect from your peers, was entirely foreign to us. We didn’t get paid. Nor was that the objective. And look what happened! We were lucky enough to operate for long enough in a space where we didn’t need it. We didn’t need the advocacy of the higher-ups to tell us we were good. We had a clique, and we were having a good deal of fun just testing each other, to see just how much we could make in terms of the work.

The way you related to pop culture, you and Guido, was a bit like, ‘We have a band, and we have things to say, and we’re not here to entertain you.’ Maybe you didn’t really intend to do this, but ultimately I feel this is why you’re still around – it’s because you still have something to say.

Failure has always, to a degree, been a close companion. A friend, ally, maybe. But, you know, it didn’t always feel that way. Failure was something we were akin to. So we didn’t require success. That connection that we gained through our insouciance was really fulfilling. It was just that you can’t do that forever. You can’t say, ‘I’m going to be insouciant forever.’ What I can do is recall what’s important, what’s of value. Why do I love teaching people? Because it redresses this need that I have within myself to create something. A recent set of pictures I did where I dressed somebody up as Frankenstein – I don’t think I’ve ever done a more absurd set of pictures – the meaning, the relevance of those pictures for me, probably ought to some degree remain private… But, you know, I might stumble across those motifs from time to time and I don’t know why, but I’ve just got to dress somebody up as Frankenstein, and I’ve got to cast a young woman blowing down a tree. I’ve got to take a fake baby and throw it in the air. Once those pictures came out in the sequence that luckily someone else had managed to stitch together for me, suddenly I went, ‘Oh Christ, look at what that means, that’s actually really quite painful.’ So, I’m very grateful that my pictures can appear in those magazines. I’m so lucky that, in spite of their absurdity, someone goes, ‘Yes, OK, we’ll give those a chance.’ Because only once they’ve come out do I realise what the fuck they’re about. Otherwise, it’s just in your head and it doesn’t become very clear. The pain of looking at those pictures is a clear indication to me that the work has value, but it’s so deeply subjective that I can’t expect, and I refuse to expect, anybody else to want to understand it.

Are you, like me, obsessed with Frankenstein? I’m obsessed with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the novel. Because it’s about creating a double of yourself.

This desire to play, to hold sway over the person that you want people to think you are, that your ego designs. In doing that, Mary Shelley is probably also commenting on hyper-masculinity and her struggles in the face of patriarchy. I think there’s a psychotherapeutic read on it, in that we all create a persona through which we think we’re going to gain some control over the way people will appreciate or experience or review us. It’s clear to Shelley there’s an inevitable failure, that your authentic self can’t be stitched together from different places, different influences. Hence why Frankenstein, the monster, is rejected wholesale because he’s so deeply misunderstood. In particular I felt when I saw the film, this accidental murder of the young child that he commits because, in his mind, he’s engaging in a game that he’s just too big for… It’s such a cripplingly sad scene and sends him on his way to oblivion. It’s that moment that gives people justified reason to want to kill him. To want to send him off into the furthest reaches of the polar ice cap, because he’s misunderstood. It’s a really profound book for me.

And how do you find profundity?

I think you find profundity because you really connect. You see something in yourself, or in fiction, or in a story that someone else has given to you. Maybe a photograph can do the same thing. I don’t think I’m just being falsely humble, but it’s hard for me to imagine that anybody would get that from a photograph that I’ve made, but it’s fine because it means that I can just carry on having a go at it.

That’s what I like about your work, that you keep repeating the same thing. I believe in the strength of repeating the same thing, and the same thing being distorted by repeating it. That’s quite interesting as a strategy. I think once we had a discussion and you said, ‘I need to attack the pictures.’

It’s true, I said that. Attack the page!

‘We didn’t need the advocacy of the higher-ups to tell us we were good. We had a clique, and we were having a good deal of fun just testing each other.’

This is your charm, you know? When you worked with [stylist] Anna Cockburn, there were clothes that you made as you were taking the photos. There were clothes that you were putting on people that were cut so they could become a new shape. Then on top of that, you would add a bit of paint or colour, not to make it look cool or nice or trendy, but just because you were finishing the whole silhouette.

I guess that was the homespun nature of the way Anna worked. I was always blown away by her thoughts and her approach. I wish that we could have collaborated more, but it was a very intense working relationship, and it was bound to end fairly quickly.

I believe in quick encounters, there are people like that.

Yes, and that was definitely one of them. When I was working alongside Anna, the important thing was to find some parity, some equality with her brilliance. So that was the challenge for me. I had to bring something from beyond the margins of the norms of what a fashion photograph was supposed to be. I was compelled to be more inventive with her. But it depends on what sound you make together. I always thought that was a really good way to measure what was going to work or wasn’t going to work, in my mind. As it came together, I felt like, ‘Oh, what sound is it making?’ All melody or no melody; whether it was dissonant or if it was tuneful. We were very different people. She was much more cerebral than I ever was. She was a very deep thinker, and I was more impulsive, more instinctual. When I say ‘attack the page,’ it’s like: let’s just seize the opportunity to grab it and reshape something. She worked more carefully with the opportunities that were presented and therefore was more subtle.

But, you know, maybe together we made a sound that shook people up a little bit. I think that was half the intention. I always wanted attention and I guess that was my funny, skewed way of courting it. It goes back to what I was saying before, like: let’s see if you really think I’m good, then look at this, and if you still think that’s good, maybe we’re in with a chance. Anna did that in equal measure. As I said, she sort of really blew me away. It took me a good time to catch up with her, really. I probably never did, but it took me a while to absorb where she was coming from. Once I’d had that chance to review things, it would push me to bring something else. I think, if I’m right, the pictures you’re talking about, I drew on and I created a little peanut character. And who is the peanut? You know, it’s me.

If we are staying with the music business metaphor, you keep sending singles out into the world. We’re entering a digital age, and you don’t have a monograph of your work. This is why I’m very interested in your particular way of being an auteur, because normally an auteur puts out a book or something that compiles all of their work.

I think the thing is, if you were brought up as a working-class kid the way I was, you weren’t told to have aspirations. What you had was your rebelliousness. In terms of this new age we’re entering, I don’t see a sophisticated way forward as to how to extrapolate more from the work that goes into a magazine. Don’t forget, I don’t have a social position with my work. There may be one, but it’s intrinsically subjective. It’s asking, ‘Is there anyone else out there?’ Whereas I think I see a lot of young photographers now positioning themselves socially in terms of a platform. You know, their medium is secondary to what they want to say socio-politically. I get that, and I support it. But does it make the work better? Not really. So, I think I’ve got to start trying to explore the medium, not for its own sake, but to explore if it could just say something better than I have found ways to say it in the past. If it’s depleting the craft or its sophistication to a point where it takes on the refrain of something which is untrained and unsophisticated, known as ‘amateur’ photography, I don’t have a problem with that. I like amateur photography as much as I like any so-called ‘sophisticated’ work. I don’t believe in the camera possessing some kind of magical skillset to suddenly make you good or bad or whatever. It’s just different. I think exploring the medium in terms of what extremes you can put it through was, for me, a very important part of working in analogue. But it’s also a very important part for me of working in digital as well. They’re totally different materials, but the approach is the same.

‘Becoming successful put me too near the edge of failure. To unconsciously survive that, I imagined ways in which I could put people off my work.’

In your work there is no fetishism in relation to the medium. It’s still a camera and you know how to handle the camera. I remember one point in your career where you were a bit lost – lost more in technical terms, disturbed by digital. Not because you were afraid of digital, but suddenly the tool you were using to record the world was not efficient.

The shift towards digital came, for me, after I’d actually taken a period of time away and not worked for a number of months. I came back and I suddenly found myself in a situation where I was almost forced, or obliged, to work digitally. At first I felt exposed because I didn’t really understand it. It was very democratised. Suddenly the authority had kind of left the photographer and it had become more of a ‘groupthink’. So you couldn’t stitch your personal position into the idea. That was a real struggle for someone like me who’d grown up the way I had. It took a while. I was listening to John Cale talk about drone and his experiences working with La Monte Young and I suddenly thought, ‘Well, that’s how digital is.’ You know, we went from a very simple process to one which was enriched with all manner of different possibilities.

The turning point came when I realised that, even if I felt I no longer had a voice, I could still sit at home, take a picture of something as ordinary as a cup, and place it in a completely different context – suddenly that felt like a powerful act. I think I got very involved in the idea of data being a very flexible material. When we listen to one of our favourite guitar players, we’re not expecting or wanting a bum note, but sometimes the bum note can become the most important note in a piece, and the feedback can lend something supersonic to a piece which might fall flat without it. So, I think the possibilities that exist in data are really important to the human imagination. In fact, they are the human imagination. It’s the transition between reality and possibility. It’s more akin to painting, except we still expect digital to perform the way a photograph did. So, once I felt like that, I thought, ‘OK, I’m going to jump wholesale into just completely cutting pictures into shreds and seeing what emotions I discover putting dissonant elements together.’ There’s a wavelength that operates between photography and data. The way the lens looks at something, or the way you can make a frame through a lens on a particular item or a moment, and then put it through a digital machine, it gives you a second chance at adding an emotional layer to that. And I think once I’d come to terms with that, it became really exciting again.

Somehow, I feel that your pictures are even more personal when using a digital medium. It’s like they’ve become closer to you. Closer to your very complex, polymorphic brain. Usually people would say, ‘OK, digital is killing our humanity.’ You were using a certain camera, a Sony, because you liked the high definition, but not so high. Then the way the light was, it’s almost like you constructed your own brush or your own hoover to suck up the surface of the world. So, do you see it like this?

I think the only answer I can give, really, is that there’s a compulsion to explore. If we go back to what I said earlier about Arnold Newman and light, he couldn’t light everybody in that same way. As an American Jew, he was bound to have a disposition for a German industrialist who’d been part and parcel of the German war machine, and this was his opportunity to utilise aspects of his craft or his practice to say something which was deep, profound and important to him. I think that finding something that is important is actually the only thing it takes to make art, right? True art. And I shouldn’t be the commentator. I’m not trying to position myself as a sort of authority on that. But if someone gets it, great. If they don’t, OK. Does that mean you stop? No. Because ultimately, you’re talking through your medium to yourself. If you feel you need connection to dig beyond the troubled surface of your own complexities, then you will see it through the pen, or you will see it through a camera, or you’ll see it through a paintbrush. If you’re not getting there because your practice has become in some way banal to you, or you’re just expected to perform and create it that way, then it is essential to change.

Sometimes you forget the essential qualities of change. We as humans cling to who or what we are and we’re afraid of change. Luckily for me, I’ve got something I can play with that gives me the opportunity to practice in a way which is less consequential. Change, in reality, is a very difficult thing for us to face. I think there are many reasons that probably explain it better than I can, why we’re so averse to change. You know, we stick to a fantasy of what works and we won’t let it go under any circumstance. But I have a medium that is easy to manipulate and helps me go forward in terms of discovering something that, as I said earlier, much to my surprise, I kind of had no real true connection to.

‘I like amateur photography as much as I like any so-called ‘sophisticated’ work. I don’t believe in the camera possessing some kind of magical skillset.’

I’m struck by how you collapse time and perspective –whether it’s a girl emerging from a hole, a forest inside a studio, or an archive image that feels both staged and real. Can you talk about how you build these layered spaces?

I’m drawn to the way you remember things. But I think the point is that, for me – and this might sound trite but it isn’t – I like to laugh when I’m working. I just want to be humoured by how preposterous it can all get.

Simply saying ‘I’m having fun’ doesn’t mean much. But in your pictures, there seems to be a deeper impulse – to be human, to laugh, to feel extremes. Do you see your work as bringing everyone into those feelings with you?

The fantasy of the experience will drive the picture, right? I think you and I have been in situations where we’ve tested what those boundaries might be. We’ve been provocative, we’ve invented challenges to keep ourselves alert, critical, and engaged. You and I have done that to each other. I don’t say that in a malicious way. We both know that sometimes there is a sort of drum roll to everything we do. It has to come out as a mild performance because the energy that goes in will also resonate in the final reading of it. It’s a circus. And, you know, you’ve got to come away from that thinking, ‘Well, we did get somewhere, I don’t know where it was, but we definitely got somewhere.’ You can go to bed that night safe in the assumption that other people are going to pick up on that and that it will have achieved at least some kind of direction that will hopefully appear to give a sense of intrigue. That’s very important to people like you and me. Sometimes that energy can be a little hard and challenging. It can even, in some cases, be destructive. But I think if we’re on our game and we’re working well together, then it’s highly productive, and that has proven to be the case.

One last thing to discuss is your relationship to nudity. It’s complex, but it feels like an important part of your work.

I would describe that part of my work as deeply adolescent. Without wanting to go into self-analysis, I think that probably would suggest that it requires some analysis. I haven’t done it for the whole of my career. It’s a part of what I do that came pretty late. I’ve utilised it to make points about photography and about desire through photography. It doesn’t necessarily have to be my desire, but of course, once you start working that way, you experience it, like it or not. And that is adolescent because it’s confused. Whether it has value, I don’t know.

That’s what I was interested in – because even if you’re willing to work in underwear, like the guy with the black mask, it doesn’t mean you’re revealing yourself. You’re still very protective of your inner self.

Exactly.

So when a naked or half-naked woman appears in your work, it feels more like citation than projection of your own desire.

You know what? I think it’s really hard to take a really good naked photograph. Have I got anywhere near that? Probably not, if I’m being honest about it. I also think it’s really hard to make a great landscape photograph. The two consist of the same thing, in that it’s very difficult to intervene. It’s very difficult to direct either of those two pictures. They can go all too easily into the form of a cliché. They can go really easily into the form of something which is kind of indifferent. I’ve tried them both, and I guess to some degree it’s an exploration.

‘The shift to digital came after I’d taken time away. At first I felt exposed. Suddenly authority had left the photographer and it became more ‘groupthink’.’

Since we’re talking about adolescence, I wonder if there’s a parallel in publishing. At The Face you were still inside someone else’s world, but with Arena Homme+ it feels like you decided to take ownership – as if to say, ‘OK, this is mine.’ Was that a kind of coming-of-age moment?

It was so easy to do that. The magazine had become about a very marginal, eroticised male image, which had gone tepid. Better practitioners had already described that kind of male beauty, and repeating it had become banal. That frustrated me, because my memory of the magazine was that it was highly erotic around the male. To repeat that constantly was, in a way, dishonouring the original creators of that universe. So I spoke to Ashley [Heath, Arena Homme+ publisher] very briefly and said, ‘I’m not interested in making images like that, but I will make a picture of an ordinary man. What would he look like? Where was he, what was the context? What was he thinking? Was he the hero? Probably not. But inside the camera, he becomes prominent.’

You really have a sense of wanting to preserve things. You can keep saying the same thing, but with a resistance to authorship. And where things have inspired you, you keep them alive in your own work.

It’s like once in my life, I was warned by a teacher to not go looking for the meaning of life in a pop song. And you know what, my only answer to him was: that’s all I’ve ever done. And it’s all I’ll ever want to do. So, the songs that stay with you cannot leave you. They just can’t because they changed you. I think that sense of irritation with the norm or what is hegemonic entered me at some point, and I don’t think I’m alone in thinking along that line. I think there’s plenty of people who probably feel the same. But do they react, and do they have the good fortune to have a medium through which to explore that? I don’t know, but I’ve got it, and I was given it when I was 17 years old. I’m inclined to be somewhat dramatic, but I think it’s probably clear that it saved my life.

David Sims, ‘I Light You Madly’, by Mathias Augustyniak, 2025.

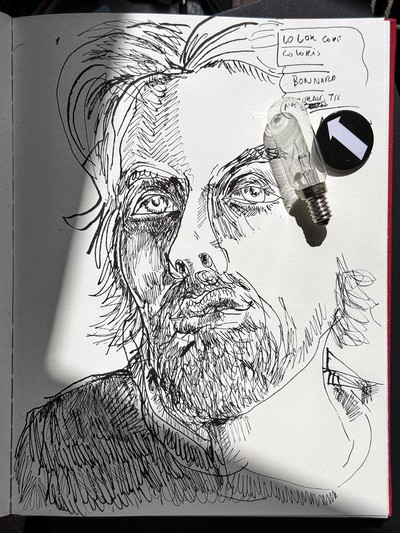

Drawn during the interview, 25 July, 2025.

(Title also serves as Mathias’ informal title for the interview)