Interview by Summer Bowie

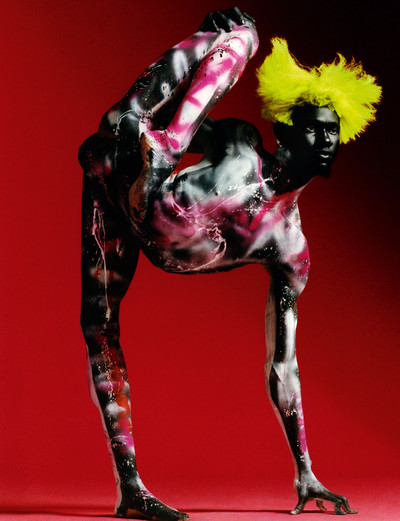

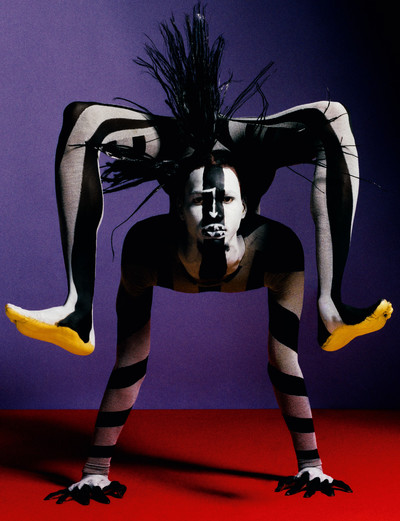

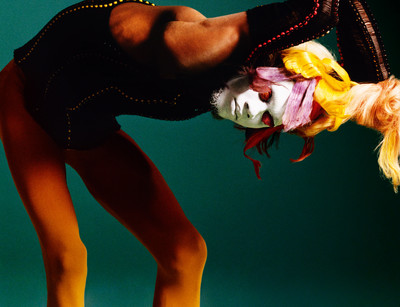

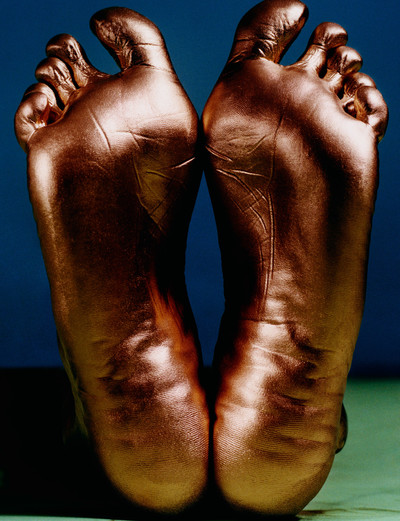

Photographs by Luis Alberto Rodriguez

Styling by Raphael Hirsch

‘When you grow up in the closet, everyone makes you aware of how you walk, how you talk, how you breathe, laugh, jump. You feel like you’re in a fish tank. That’s become a useful tool later in life, and in my photography, because I am very aware of somebody’s posture. I’m aware of what their fingers are doing. I’m aware that they are super light in their shoulders, but they’re tense as fuck in their knees. I’ve become like an X-ray machine.’

Luis Alberto Rodriguez does not tell his subjects how he wants them to look; he builds an environment that makes them feel it. His figures are always comfortably at ease or at the very apex of a gesture, such that your brain completes the unseen range of motion. In a film accompanying his cover story for the eleventh issue of Beauty Papers, Kristen McMenamy bounces and twists eerily in vintage couture. His covers for Harper’s Bazaar with Gisele Bündchen and Rihanna move in ways that feel equally distinctive to their subjects. Bündchen leaps, skips and lunges in a wide-knit pompom-covered Bottega Veneta dress. Shot in black and white, Rihanna balances in ballerina-like relevé in a Dior gown and sits high with one leg folded over the other. In these shots, Rodriguez uses something unique to his work – his background as a trained dancer – to breathe life into the otherwise inanimate page.

After graduating from Juilliard and touring the world with numerous European dance companies, Rodriguez realised that his enthusiasm for taking portraits of his dancer friends was more than just a hobby. He was encouraged by his late mentor, Black queer dancer, artist and self-proclaimed ‘creator and instigator’ Mac Folkes, to submit his work for the Hyères Festival of Fashion and Photography in 2017. He took home both the Prix du Public and the American

Vintage prizes and since then has been welcomed by fashion with open arms.

Even though Rodriguez and choreographer Jermaine Spivey, his longtime friend and lifelong confidante, may have taken different routes, both share a commitment to embracing collaboration. While Rodriguez guides models into channelling the kinetic power of what they are wearing, Spivey studies his dancers’ bodies and finds ways to challenge their default patterns of movement. They both learned through experience that the body does not know how to lie because our motor reflexes fire infinitely faster than our thoughts. Here the pair speak together about their shared history and approach to working with the body – Rodriguez through the camera lens, and Spivey through choreography.

Summer Bowie: You two go way back. When did you originally meet? Was it at Juilliard?

Luis Alberto Rodriguez: We actually met before Juilliard. Alvin Ailey has a summer program and we met there when we were, like, 16.

Jermaine Spivey: In 1997.

Luis: We don’t have to date ourselves! [Laughs]

Jermaine: [Laughs] It’s dated, OK.

Luis: Well, he was in the summer program and I had gone to a ballet program. That’s when we became aware of each other, and then eventually we found out that we were both going to Juilliard.

You attended Juilliard at the same time and you both had very formative experiences with William Forsythe, but he impacted you in slightly different ways.

Jermaine: He impacted both of us before we even came close to meeting him in person. When we were in school, his company came to perform at BAM [Brooklyn Academy of Music] and it was mindblowing. I didn’t know how to watch it. It wasn’t until years later that I was mature enough to know what people were doing when they were working with him. He changed all of dance forever, and people are still trying to imitate and chew on the information that he offered.

Luis: The company came to New York when I was in my late teens, and it was quite life-changing for me. At Juilliard you’re taught that you should be incredibly versatile, but that was never really me. I felt a little bit odd compared to the other people in class, and I think that oddness followed me through my career. When I saw Forsythe and Ohad Naharin’s companies, there was such excellence, but also individuality – it felt like there was room for me. All the company websites back then just had a headshot and a nice ballerina pose, but with Forsythe’s company, people were upside down, lying on a couch, or they were on the floor. The posters were blurry, chopped, whatever. It was this world that felt like a science lab. I would look at Forsythe’s website and was obsessed. I would try to either do what they were doing on those posters or take pictures of my friends doing it. It’s what initially got me excited about photography. But I had no plan whatsoever to be a photographer or to be working in fashion.

‘My father didn’t even know what Juilliard was. He answered the call from Juilliard to tell me I was accepted and thought it was some girl named Julia.’

Hungarian photographer Martin Munkácsi was a foundational influence on Richard Avedon, who said that ‘Munkácsi brought a taste for happiness and honesty and a love of women to what was before him a joyless, loveless, lying art.’ Now that fashion photography is no longer reserved for women’s magazines, how would you say you’re carrying that torch?

Luis: What’s important for me is to carry my history. This whole journey into fashion photography has been really non-linear for me. I never assisted anyone. I was thrown into the deep end and it was sink or swim. I’ve always had a strong connection to what moves me. And whatever that is, it’s not vanilla. I’ve always been interested in transcending, but I try not to focus on how I carry it forward. I’m trying to be great and to honour my truth.

Jermaine: We came up in a time and place where it was valued to adapt what you have to a very specific aesthetic. I prided myself on the ability to do that, but Luis was already absorbing it and turning it into something more individualised. It took me many years to find myself, and he was a big influence in a lot of that. His eye, his taste, his intuition has always been intact and very specific. Like, he was the first person I knew to wear Crocs. Ever!

Can you talk about your sartorial sensibilities a little bit?

Luis: When I was younger, I was much more colourful. I would wear beads and I had bright yellow Crocs, striped pants, polka dots. It was just a lot. But as I’ve gotten older, I’ve become a bit more basic in my dress. Much more worker vibes, very everyday classic.

Jermaine: But it’s also a rebellion. He’s always going against what everybody else is into. Now that bold and colourful are in, he’s keeping it rebelliously classic.

Luis: When I was 21, I moved to Europe, where I’d get these huge opportunities, and then I was fired and fired and fired because of that rebellion, and it was difficult. Eventually I moved to Sweden, which is very homogenous. I wanted to fit in and I became a bit more conservative. Then I moved to Berlin and I didn’t have any money. During the 11 years I was there, I had a big transition from dance to photography. So, in the end, I was spending all my money on film.

Jermaine: It’s also because we were both quite conservative in every other aspect of our lives. So, the part of you that was not allowed to be free was coming out in your clothing. I was not even ready to let it come out through my clothing. Now that you’re really living your life, your life expression is doing that, so your clothes don’t need to.

Growing up, you were essentially living a double life, Luis. Your dance life was kept completely separate from your home life, and you didn’t come out until your mid-20s. It makes sense that rebellion would manifest in the way that you dressed.

Luis: Yeah, exactly. My parents gave me what they could and we have a great relationship, but there was not a lot of money. It was public housing, food stamps, all of it. My parents don’t speak English and there were a lot of things that I didn’t know how to process. The way that I survived was by compartmentalising my life. I got into these after-school programs to keep kids off the streets, but I was ashamed of them so I didn’t invite them to my shows. My father didn’t even know what Juilliard was. When he answered the call from Juilliard to tell me I was accepted, he thought it was some girl named Julia.

Jermaine: When you’re in a space where being gay could potentially be a problem, you don’t want to hinder your chances. I’m from inner city Baltimore. Dance was my ticket out. So, on a subconscious level, you’re always thinking, ‘I cannot let anything get in my way – which includes myself!’ I came out after Luis, when I was 29. I met my partner, who I’m still with, and we were living together before I officially came out to my parents. It was difficult for me to incorporate that part of myself and to live it truthfully, but at a certain point it was holding me back artistically.

Luis: I was quite repressed in my sexuality and genuinely confused. But there was also a part of me that was very free. My parents didn’t really know what the hell was up with my dancing, but I was like, ‘You will not be stopping me. I’m just letting you know.’ And the same thing with my sexuality. It got to the point where it was like, ‘How about, fuck you?’ As gay men from a different generation, sometimes your emotional growth is a little bit stunted because you don’t have those years as a teenager to develop and date people. And when you allow yourself to feel those feelings, it has a ripple effect on everything you do.

In your photography, is it difficult to translate the postural ideas that are innate to any dancer to subjects who don’t speak that language?

Luis: It’s quite frustrating, but it can be such a beautiful challenge to work with people and meet them where they’re at. In my book O, it’s all nudes with all different types of people. One of the guys was a 70-year-old blind man and I’ve never had an experience like that. There was no music playing in the studio. He couldn’t see me and follow my directions, but all his other senses were so in tune. So it became this meditative state where I’m working with his body and learning what he’s capable of doing, which often surpassed my expectations. With a dancer I can go deeper in some ways and it’s an easier flow. But I’m trying to work on a more sensory level, so if they’ve been raised with classical dance, it can be pretty hard to convince them to let go. And then if I’m in a fashion context, and I get one of these models who are 17, 18 years old – insecure, and don’t know their left foot from their right foot in a pair of heels – I actually enjoy the challenge of finding where she’s locked in her body. Then I work with that and make her feel at ease.

‘The clothes already tell such a story. I see the restrictions in the clothes. I see the fabric, I see how it moves. The clothes really dictate what’s possible.’

I’m curious about how you approach the challenge of teasing out the particularities of somebody’s body, everything from their posture to their cadence to where they hold their tension so that you can exploit it for the right reasons.

Luis: I usually like to start with someone sitting, something for them to feel grounded in. I’ve worked with some celebrities and sometimes I can tell they’re not comfortable in front of a camera. You have to make them feel at ease. I also do research before I see them. I watch interviews, I see how they’re holding themselves, I see how they walk. The thing is, when you grow up in the closet, everyone makes you aware of how you walk, how you talk, how you breathe, laugh, jump. You feel like you’re in a fish tank. That becomes a useful tool later in life because I am very aware of somebody’s posture. I’m aware of what their fingers are doing. I’m aware that they are super light in their shoulders, but they’re tense as fuck in their knees. I’ve become like an X-ray machine.

It sounds like a gestural code switching that you were forced to learn at a young age and now you’re like a Rosetta Stone of body language.

Luis: Exactly, everything from how your eyes are looking at the camera, how your neck is placed, where your shoulders are. Are you breathing? Are you really sitting on the chair? Are you clenching your butt cheeks? Sometimes I look at editorials and I can see what they’re trying to go for. Somebody told the model, ‘This should look elegant and relaxed. Look like you’re thinking.’ But there’s no real understanding of the weight of the body. There’s no connection.

Jermaine: The body does not lie. When it comes to non-dancers, you’re really trying to get someone to feel the moment and not pose it. You can’t make non-dancers look like dancers. You have to give them references. Maybe it’s a famous scene where someone fell out of a window. You’re trying to get them to imagine something, because as soon as you start imagining something, the body responds. But if you’re not thinking about anything, the body responds with what you’re not thinking about.

What’s it like trying to balance your vision with somebody who has a personal brand they’re trying to maintain?

Luis: I’ve had incredible opportunities, but it can also be a nightmare. I understand the theatre very well, so with actors there’s a certain language that you can tap into. But with musicians, some can be really disrespectful. They can speak to you like you’re nobody, and the reality is that we’ve actually had very parallel trajectories. I have worked with the best of the best in dance. I have performed all over the world at opera houses, in every major theatre. It’s a psychological game that I have to play so that we can all get what we need; me, the subject, and the magazine. It’s not for the faint of heart. You always have to be very professional, always think about tomorrow, and never leave with regrets. I worked with Rihanna, and it was incredible. She was so generous and warm. She’s so in control of her body. There is no hiding. She’s just a bad bitch. Working together felt like a collaboration, but a lot of times you don’t get to that place because there’s so much ego. So, I try to make that connection and I try to be as fast as possible. Sometimes you only have 40 minutes, so you learn to read the room.

Jermaine: Ultimately, if you’re showing up with an attitude of, ‘I don’t want to do things,’ then you’re not showing up to do the job, because the job is collaborative. We all have to work together.

Jermaine, you compose movement on and with people’s bodies and then you find ways to complement their movement with costume. And Luis, you’re given a body in costume, and then you prescribe posture or movement to bring the garments to life. How does the order of that process affect the outcome?

Luis: The clothes already tell such a story. I see the restrictions in the clothes. I see the fabric, I see how it moves. The clothes really dictate what’s possible. I was just shooting the editorial for this and some of those clothes were really delicate. And so, I have to factor those limitations into what I can do with a contortionist’s body whose abilities go beyond normal body movement.

Jermaine: I made a piece called Extant in 2023 for Ballet Flanders in Antwerp, where we wanted the dancers to be restricted by the costumes, so we chose denim, the kind that doesn’t really stretch. Sometimes people were weighted down with layers of denim and from underneath that they had to fight for the clarity of the choreography. Oftentimes though, they want you to give the concept for the costumes a year in advance; long before you’ve made the dance.

‘The body does not lie. With non-dancers, you’re trying to get them to feel the moment and not pose it. You can’t make non-dancers look like dancers.’

Edward Steichen was a pivotal figure in photographing not only dancers, but fashion. He brought drama with his use of lighting in the studio. Has your experience of watching how stage lights bring choreography to life informed your own use of studio lights?

Luis: I was quite intimidated in the studio at first. I didn’t think I knew those codes until I remembered that I grew up with stage lights. I know how lights can be used to create mystery or suspense or confusion. I’m quite a melancholic person in general, so there’s this moodiness in the way I light a photo. I don’t know if it’s sadness, but it’s drama.

There’s a sculptural component to your photography that goes well beyond the realms of dance. Do you have specific artists that influence your practice?

Luis: From the beginning, the work has been quite sculptural, but it was never an intention. It was just what I was drawn to. In the early days, I didn’t have any photography references. It wasn’t until I moved to Berlin that I met my late mentor, Mac Folkes. He started showing me Irving Penn, Viviane Sassen, Peter Hujar, Nan Goldin, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon. I saw Richard Avedon’s photos of the American West and developed a huge respect for him.

In your first book, People of the Mud, you photographed people in County Wexford, Ireland. Tell me about that.

Luis: I was awarded this residency in 2018 and then sent to this farm town in the middle of nowhere to make a work about cultural heritage. I had a picture that I took in the Dominican Republic, where my family’s from, of two brothers embracing. It just looks like this knot of bodies – it’s a love that’s so intense, it’s suffocating. Originally, I wanted to extend that to an entire family. I wanted to photograph a huge family wrestling. But once I got there, I was like, ‘This is never going to happen.’ Then I learned about a sport called hurling. It’s kind of a religion in Ireland and that was my connection point. The players have grown up together; some have been on the same team for 15 years. So, there’s a great sense of intimacy and also legacy. I would film the game and then go home and watch it in slow motion and find motifs that were created while they were pushing, pulling and lifting each other. I’d take those, do sketches, then I’d take those sketches back to the players. And so, it became collaborative. I was very nervous about going there as a person of colour but they were so welcoming. I learned about the colonisation of Ireland by Britain and I photographed traditional Irish dancers.

Can you talk about your process of casting and conceptualising the images in your book, O?

Luis: It started during the pandemic, when I was in Berlin. My father was in New York and he has emphysema, so I had a lot of anxiety that he was going to die from Covid. And then, on top of that, it was also the election coming up. I did this picture of a friend for his album cover where he’s falling backwards and it’s almost like he got the wind knocked out of him. I was like, ‘Oh my God, I want to do people collapsing.’ The idea was like, if everyone’s collapsing, how much collective will does it take for us to bring ourselves back up? I wanted to bring my parents into this. So, I photographed my father for the first time and my mother does these very Dominican coffee cup readings for people when they’re looking for clarity. For the casting, I was looking at this as a portrait of humanity. I had this really big woman, and it just felt like this mass of body. And then I had someone who was really bony. Then, when I photographed that blind man, he’s in this pose where he’s looking right at you, but he can’t see you – that is still one of my favourite portraits that I’ve ever taken. When you are hit with something, you don’t really choose how your body reacts. You just react.

Director of photography: Kyle May

Talent: Mohamed Bongoura

Casting director: Maria Osado

Hair: Joey George

Make-up: Sam Visser

Set designer: Zacharie Adams

Sound: Samuel Van Der Veer

Video editor: Jubal Battisti

Production: Second Name Agency

On-set producer: Lindsey Gomez

Photography assistants: Roy Beeson and Doni Towers

Styling assistants: Storm Foster, Gabriella Georgie, Chris Lee, Wynn Salman

Hair assistants: Skye Melena

Make-up assistant: Aya Tariq and Miki Ishikura

Set designer assistants: Syavash Jefferson and Vango Jones

Production assistant: Kristen Miller

Post-production: Dtouch

Special thanks to Ed singleton at Yello Studio