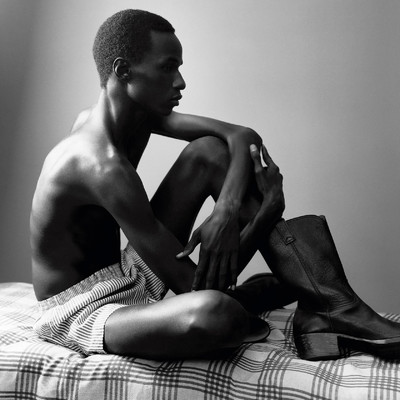

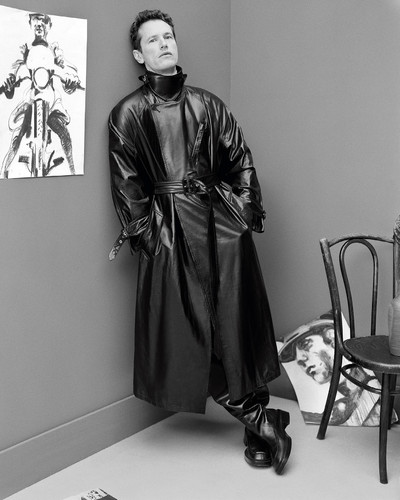

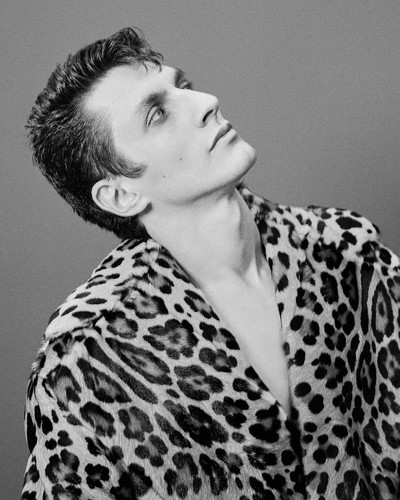

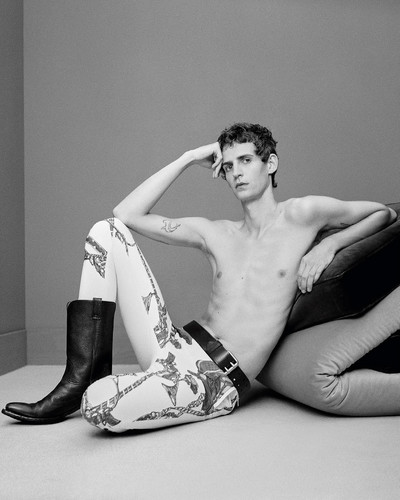

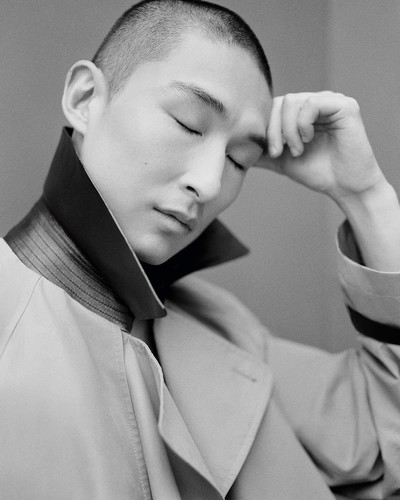

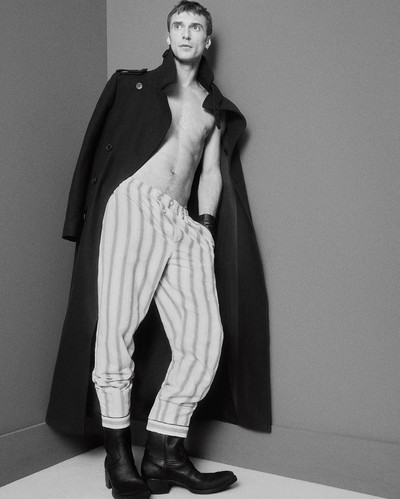

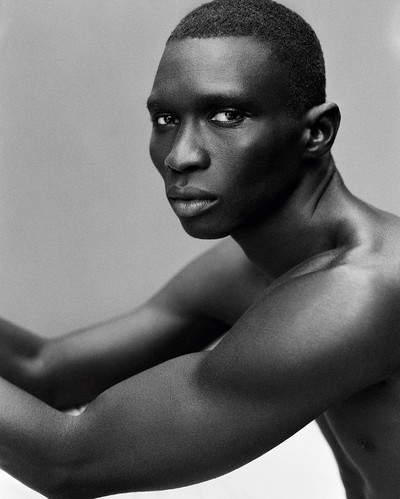

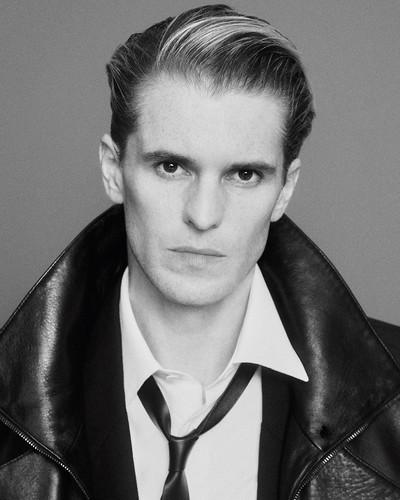

Interview by Jerry Stafford

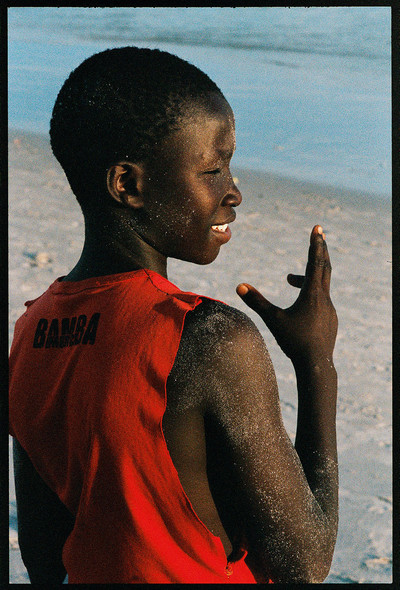

Photographs by Malick Bodian

Styling by Robbie Spencer

‘I think my role is to help my people realise their beauty, in the same way that people in fashion helped me realise my confidence.’

Malick Bodian doesn’t just walk into the room, he glides softly as if on an invisible cushion of fragrant air. He doesn’t simply sit, he drapes and folds himself into a chair like a silk Hermès scarf. And he doesn’t speak, he weaves delicate syllables and sentences together with long elegantly-manicured fingers as he describes his early childhood in Senegal and his adolescent peregrinations throughout Europe.

At the age of 13 he left his birthplace to join his mother in Italy. From there he made his way to Paris in 2018 after he was discovered by a model scout at 19 while working in a restaurant in Corsica. As one of a new wave of West African male models, his meteoric rise to fame on the catwalk quickly led to lucrative commercial work and close relationships with some of the most influential players in the industry – designers and photographers alike.

His early interest in the visual arts, particularly cinema, quickly and naturally led to photography and a desire to document his own experience as a model. Bodian continues an illustrious lineage of West African studio and street photography which includes such legendary portraitists as the Malien icons Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keita, Cameroon’s Samuel Fosso and the Beninois Roger DaSilva, who lived and worked for most of his life in Dakar, Senegal. Their revolutionary visual aesthetic, with its forensic study and celebration of Black elegance and style, underscores Bodian’s exploration of photo reportage and fashion photography, and continues to inspire his own practice.

Bodian now divides his time not only between work as a model and as a photographer but also between a home in Senegal where he has decided to return to live, and his apartment and studio in Paris. He is equally at ease on a red carpet in Venice or New York as he is exploring the vast Northern plains of Kenya or the metropolitan cacophony of Dakar. Polyglot and Renaissance Man par excellence, Bodian navigates each medium to which he lends his tasteful attention with elegance, clarity and intelligence while retaining his own unique sense of humour and ambition.

So, in the words of his style icon and hero, American actor Eddie Murphy, ‘Whatzupwitu, Malick?!’

Jerry Stafford: Let’s talk a bit about your childhood. What are your first visual or sensorial memories of Senegal where you were born?

Malick Bodian: The place I grew up is called Mbao and every time I think about my childhood, I think about a specific beach where I spent a lot of time. There is also a village, Missirah, where my grandmother used to live and where I learnt how to ride a bike. It was a village where I also encountered snakes a lot. The reason why I fear snakes comes from this village, which was part of the biggest safari park in Senegal. I have really incredible memories of these places, it was almost like a fantasy.

Tell me a bit about the house you grew up in as a child. What did it look like?

I grew up in a traditional circle house. In the centre of this house were two trees: a big one in which we’d sit and have lunch, and a mango tree that we called papaya mango – the mangos tasted so good. In this kind of house, you have a courtyard with only sand and then you have the trees with the kitchen at the back. To the left are rooms where everyone sleeps, and at the back of the house was a huge kapok tree that scared me at night.

Can you remember any particular traditional aspects of Lebu culture when you were growing up?

The Lebu are the people of the sea, they live next to the beach. They’re not really my people because my father comes from Casamance, which is in the south, but I was born in Mbao, which is 10 minutes from the beach, so the Lebu kind of lived there; they were always in the sea or next to the water. They’re like the fishermen of Senegal.

Were you aware of any ceremonial practices in the community?

There was one called tajabone, which was a ceremony where you dress up and go and ask for candles and money. There was another memorable ceremony, tabaski. It’s a Muslim festival but in Senegal it’s kind of transformed and they make it their own: once a year you go to your favourite tailor and you make a specific dress. Men and women wear their custom outfits. It’s a very beautiful festival and now that I work in fashion, I realise how connected I am to this ceremony.

‘I was always in my mind, quite cerebral, but in Senegal, you don’t have time to be with yourself. There’s always things going on, it’s very social.’

What was your relationship with your parents and siblings like while you were growing up?

I only lived with them for three years in total. My mum left for Europe when I was young. I never really lived with her. I didn’t know my father because they were separated and he lived far away. So I grew up alone. I remember my mum always moving me from one place to another. First we were in Ngaparou when she was working as a housekeeper and then she left for Europe. So she sent me to Nianing, which is a village where her best friend used to live and the family was Catholic. Because I was born Muslim, my grandmother came to the village and kidnapped me. She was like, ‘There’s no way you’re growing up Catholic!’ Very funny. Then she took me to Missirah, the village I just mentioned, where I spent most of my time and where my grandmother educated me. My mum’s two sisters were also there, so I grew up with my cousins and my aunts. And then they sent me back to Mbao. I lived in an apartment there with my siblings and I went to school, and then from there I came to Europe.

Were you an active, social child or more cerebral?

I was always in my mind, but in Senegal, you don’t have time to be with yourself. There’s always things going on. There’s always something to do, especially when you’re young. It’s like you have no choice! So, it’s very social. If you don’t want to eat at your house, you can go to someone else’s house and eat, it’s a very normal thing. Everybody kind of lives at each other’s house, it’s very open.

Who were your heroes or heroines at that time, and what were your dreams as a child?

I think when I was young, my hero was Kunta Kinte from Alex Haley’s book and the TV series, Roots. I heard a lot about him and was inspired because he was born next to the village where I grew up, on the border of Gambia, next to the Kunta Kinte island. Then there was my mum. I admired my mum a lot at that age because she was travelling, trying to find us a better life. I always dreamt of becoming a footballer, then when I was around 13, I started dreaming about working in cinema. I didn’t know what exactly, but I knew that somehow I was kind of connected to this world. But there was football, mostly!

‘Living in Sardinia and Corsica made me feel like a stranger, an alien, someone not desirable. So when I got scouted as a model, it felt like a joke to me.’

Why did your mother decide to move to Sardinia and then to Corsica? What was her motivation and how did you experience the displacement and this huge existential change in your life?

My mum moved to Sardinia because it was small, so it was an easy place for her to find work. Then she fell in love with an Italian there, got married and stayed. When we came, my older sister and I lived with her. I have another sister who is older but she couldn’t get a visa. So, we lived with my mum the first year and she was very happy to have us there, but I think at some point it kind of became a weight. My sister wasn’t really working and I didn’t want to work, I wanted to go to school and play football. Then at some point, she sent me back to Senegal because she felt disappointed that I didn’t want to go and work like the people who go to the beach and sell clothes and Chinese bags. I told her that I wanted to keep going to school. So she sent me back to Senegal as a punishment, which is something that many African parents do. When I eventually went back to Sardinia, my other older sister had managed to go to France, to Corsica. And that’s the reason we moved to Corsica. Things then started to become very difficult at home. I was 15 or 16 and at some point it was decided that I go live in a children’s home. But I still went to school and played football, and because I was doing so well in my studies, I was given my own apartment for free. In my last year in Corsica, when I was 18, I was working in a restaurant every summer – and that’s where I got scouted as a model.

Moving to Sardinia and then Corsica, did you feel alienated?

I felt totally alienated in Sardinia because it’s an island, you know, and all the Black people were doing the same thing, some kind of selling. I think I’ve always been someone who’s quite political, and even when I was young, I always wanted to do something different. I didn’t want people to have a bad image of my people, so that’s why I wanted to go to school. I was the only Black person in both my school and my football team. But I am someone who adapts very well. I remember when I arrived, it was June and they told me that you need to speak Italian in order to integrate with the school by September. I learnt Italian in three months over the summer by watching Italian cartoons. I had no choice.

When you came to Sardinia you spoke French, English and the local dialect?

Just French and the local dialect. I felt very lonely for a long time. In fact, the whole time I lived in Sardinia, I never once had a girlfriend or any kind of relationship at all.

When you got scouted in the restaurant in Corsica, what was your reaction to being picked out? Had you ever considered modelling or fashion as a career?

No, not really. I never thought about it because I never thought of myself as being beautiful. Living in Sardinia and Corsica made me feel like a stranger, like an alien, like someone who is not desirable. So when I got scouted, it felt like a joke to me. I told the guy to fuck off, you know? I thought he was making fun of me. But then he really insisted and my boss at that time was like, ‘You have nothing to lose, the guy just wants to take a picture of you.’ The next morning, he messaged me saying he’d like to see me again to take another photo, because it was too dark that night. So, I saw him again, then he scouted me for this editorial for Double magazine.

So what happened next?

When the editorial came out an agent called Benoit Guinot in Paris saw it and he was the one who really scouted me; when he saw the picture, which was just a silhouette shot by Jack Davison, you couldn’t even recognise my face! He was like, ‘I like your profile.’ It was insane! And then he was like, ‘You have to come to Paris, and I will make you a model.’ It was August and I was working that month because I wanted to move to Nice to go to university.

‘The very first photographs I was taking were oflandscapes of Rwanda and of Tanzania, shot from the plane while I was travelling as a model.’

What did you study at university?

Foreign language studies, but then Benoit told me I should go to Paris for fashion week – and that’s how I got to walk for Valentino, Dior, Kim Jones’ last show for Louis Vuitton, and that’s how I met Haider Ackermann.

How do you think you were perceived as one of the first important wave of West African male models?

When I entered fashion, it was very positive. It was a moment in my life where I had no confidence in myself; then I arrived into this world and it gave me so much confidence. Of course, the reality was that there were not many Black people but I didn’t feel it. That’s the reality, but there’s been a lot of progress.

This period is also on the cusp of what became an extremely interesting and creative time for the Black artistic community, both in fashion and photography, and then the Black Lives Matter movement gained a lot of momentum. Do you feel that you were part of this powerful wave?

To be honest, the Black Lives Matter movement never really touched me. I am someone who never gets carried away with these kinds of events. I always felt like someone who is a human being on this Earth first and foremost. I’m a very open-minded person but I never really got attached to Black Lives Matter as a movement. I think at some point I was influenced by everyone talking about it on Instagram – as we all were. But then I realised that I didn’t really know what I was talking about. I tend to stay calm when something happens and really think deeply about what I am going to say and how I am going to engage. I’m very connected to Africa and for me, I acknowledge when things happen in Africa, it just touches me more. A lot of times America has used Black African people as a tool for their fight. We don’t have the same reality. It’s everyone’s war, but it’s not necessarily their war. It’s a very sensitive subject.

As this movement was gaining momentum, Covid hit. Where did you spend that period and how did this time influence you?

Covid was horrible for a lot of people, but it was the most important thing that ever happened to me. I was in Paris, living in my apartment in Bagnolet, and Covid was literally the thing that woke me up. I am sad about everything that happened, and I wish it hadn’t happened, but I am so grateful that I had that time alone. I felt depressed, but at the same time I came to acknowledge all the privileges that I had. As I said, modelling gives you a huge amount of confidence, but then at some point it gives you too much confidence and you can take everything for granted. You get to travel, you get to visit all these countries, you get people taking photographs of you, who make you look beautiful, do your nails, do your hair, your make-up, give you all these compliments. It’s an incredible job! But until Covid, I didn’t realise it, I was just like, ‘Yeah, I’m a model now.’ I did so much in the two years between 2018 and 2020. I went to Japan, China and America so many times – I would have never gone to these places without modelling. More importantly, I also realised that I didn’t know my own country at all. I had this sense of guilt and I was like, ‘I have never actually explored my continent.’ So I promised myself that when this was over, I was going to go back home. I wanted to travel around Africa, and that’s how I fell in love with photography. I had been taking pictures since 2018, since I began modelling, but it was never a passion, but when I went home and I started doing documentary photography, I truly found a purpose.

When you went home to Senegal?

Yes, and then I began to travel in Africa. I loved doing documentary photography but I didn’t know how to bring these photos into the fashion world. I learned by finding a collaborator, and that was Ibrahim Kamara. He was one of the first people I met who gave me the desire to photograph fashion. He is an incredible stylist but when he was travelling with me he was just adding a hat on a model, always something small. And that’s how I realised that I could actually take real images in fashion, in an almost documentary way.

Where did you travel to with Ib?

The first time we travelled together, and how we became close, was when we went to his home in Gambia. Then from Gambia, we took a car and travelled to Senegal. It was such a long trip, and on the way we were stopping and photographing people. We did this series for Luncheon called ‘Senegambia’.

Since then, you’ve successfully continued to work both as a model and a photographer. How do you navigate both?

I realised quickly that modelling wasn’t going to be forever. It was something I loved doing, but it wasn’t enough. I never had the idea of leaving modelling for photography, but I think some people tried to put it into my head that I couldn’t do both. I was always like, why not? You know, if Virgil was doing design collaborations with Ikea while being a Vuitton designer, I could also do two things. So I still do both.

You’ve worked closely, both as a model and as a photographer, with leading designers like Grace Wales Bonner, Kim Jones and Matthieu Blazy. How did these collaborations evolve?

When I first arrived in Paris, I was a bit intimidated by everyone. All the designers, the casting directors… Kim was someone who inspired me when I met him at Vuitton. He was so humble at such a big moment in his career. Then when he went to Dior I became a Dior boy and we became friends. I worked with Matthieu Blazy at Bottega Veneta because of [photographer] Pierre Debusschere. Pierre was one of the first people I told that I wanted to be a photographer. It was on his set while he was photographing me for a magazine. He was very helpful, very encouraging. Pierre was working for Matthieu as image director for Bottega Veneta, and he asked me to take photographs for the first campaign because Matthieu wanted to create something new with young photographers. Matthieu chose my work to be the first image of this new era, because he thought it was very real and positive. As for Grace Wales Bonner, she’s someone who knows exactly where her inspiration comes from: Africa. I love that about her, I like people who use their inspiration well. She does a lot of research, which I think is important. I felt connected to her, to her brand, and the first thing we did was a campaign in Ghana on the streets. I like to experiment but I also love to take photographs that are very raw, with real light and this was something that Matthieu and Pierre were also pushing.

Tell me about your project Voyage Temporal, your so-called return home to Senegal to document members of your family.

I went to Senegal straight after Covid and realised that I was a stranger there. Before, I would go every two years but after Covid I started doing these trips whenever I wanted to. I got myself a map and I’d be like ‘I’ve never been to this lake, I’ve never been to this town’ and I’d just go. While I was travelling, I was taking pictures, but I had no specific purpose, no objective, it was just to explore and to get to know my country. So, I was going to Senegal almost every month for four years and after a while I put all these pictures that I’d shot together. I am inspired by Magnum photography and I realised that all the black-and-white images I had taken were images of old things: old objects, old buildings, old people as well, and people who dress like in ancient times, people who don’t want to change who they are. Most importantly though, I went to visit my father for the first time ever in 2021, and at the same time I met and photographed my grandmother for the first time.

How has this project changed you, both as an artist and as a person?

The Senegal trip was a complete turning point. Before that, I thought my future was here in Europe. This is something that a lot of African people believe; they think the future is in Europe and that there is nothing at home. For me, it became the opposite. I realised everything was at home, there was so much inspiration, and I was much happier there. The country has progressed a lot.

‘Collaboratoring with Ibrahim Kamara gave me the desire and confidence to take ‘real’ images in fashion, in an almost documentary way.’

Where is home to you?

Home is Senegal, and I’m grateful that I realised this early on. The African community is losing its talent because we’re manipulated to believe that everything the West does is better. Of course, lots of things there are good, but it doesn’t mean that what you have at home is not.

Your interest in film is becoming increasingly important in your artistic practice – tell me about that.

I always knew I wanted to be a filmmaker. At first I always wanted to be an actor, but I want to make movies because I love telling stories. I love to entertain people, and I would love to show them the elegance of my people. I’m very inspired by the Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène. He was very radical.

Tell me a little bit about the film you’ve been working on in Rwanda.

This is a fiction documentary about the Rwandan side of Lake Kivu. One day I was recording the lake and its fisherman with my camera and suddenly I noticed this place where kids would jump. I was really attracted to that place because it reminded me of my childhood in Senegal. So I started recording the conversations these children were having facing the other side of the lake: the Congo side. And the fishermen were also fishing between the Congolese side and the Rwandan side. I wanted to document this: the fishermen living day by day, and these boys in their childhood, a childhood that reminds me of my own. While on the other side of this lake, we know there is a war, there’s darkness. I want to highlight our ignorance. The documentary is about the beauty of life while, at the same time, learning to question yourself.

Can we talk about the Costume Institute’s exhibition, Superfine? What are your thoughts on its theme of Black dandyism and how were you involved in the conversations around it?

American Vogue reached out to me to do a story about dandyism and right away I wanted to do a story about African dandies. I’m so sensitive about America, especially about Black Americans, because I always think that they are not African Americans. I think they are Black Americans and as long as they consider themselves as African Americans, people will never consider them as Americans. We need to stop using the term Africa just because they’re Black. This separatism is what creates problems. So it was important for me to explore a very precise narrative. African dandyism is, for me, situated in Congo where they have the sapeurs. This is pure dandyism. Then there is also the work of Malick Sidibé who was an incredible photographer. His subjects were just so elegant.

Who are the greatest exponents of Black dandyism, past or present?

Naomi Campbell. I don’t think there’s anybody like her. For me, it’s completely her. I also love André Leon Talley, of course, and he inspired us for the American Vogue Lewis Hamilton cover! Dandyism for me is also Eddie Murphy, I don’t understand why they didn’t invite him. He is a huge inspiration to me, and he also inspired my own red carpet look!

You collaborated with Chanel, right?

The inspiration was Eddie Murphy’s suit in the film Coming to America! It was perfect. I showed it to the Chanel team, and they were like, ‘Oh my God, we have a jacket like that.’ And I was like what? And then they made the hat custom. They made the shoes. Everything they did was custom. It was a privilege.

I remember going to your show, Sénégal, voyage temporel, and watching you take a group of students around the exhibition. It was very moving, actually, as they were clearly inspired not only by your work but by your grace and generosity in sharing this time with them. Do you feel a particular responsibility, as a Black artist from West Africa, to work with your community and inspire the next generation?

Absolutely. Sadly, when you’re a Black person, the moment you are in a creative industry and you are considered a little bit, you come to represent Black people. Everything you do is important. If you do stupid things, it can affect not only you, but also your people. So I have started taking myself much more seriously and I’m very careful. To answer your question, I absolutely feel responsible for everything I do, every work I bring out, I want it to be as good as possible and have a meaning.

You have also travelled to the DRC to photograph mountain gorilla conservation projects, and to Sierra Leone to document the amputee football team. These must be rewarding but also challenging commissions. How do you see your role as a photographer on this kind of assignment?

I love to occupy different universes in my life. You need to have balance. I do fashion photography because I need balance between fashion and being a model. And then I do documentary photography because I need balance in photography in general. I can’t only do fashion photography, it would drive me crazy. So that work is very important to me. It’s maybe more important than fashion.

‘The precise narrative of African dandyism is, for me, situated in Congo where they have the sapeurs. This is pure dandyism. Pure elegance.’

Your photography is often about a relationship between subject and place, has this always been the case?

Yes, for sure. The very first photographs I was taking were of landscapes, shot from the plane while I was travelling as a model. In Africa, the first photographs I took were landscapes of Rwanda, of Tanzania. But for this System shoot, we built something specific. This year, I’ve been working on how I’m going to photograph in the studio. I don’t like this backdrop thing. I can do it. Everyone can. So I want to find a way to build the outdoors, but inside.

You also have a passionate interest in architecture and have designed and built a house in Senegal. What does this house mean for you?

The house is literally all my modelling career savings and I built it in the place where my mum and I first lived in Senegal, Ngaparou. I built it to thank her for bringing me to Europe and for everything she had done for me. I didn’t take it lightly. I always want to do things with grandeur. I didn’t want to make a house just to make a house, I wanted my mum to have a house that was very special, one in which she felt like she could travel while inside it. I took a lot of inspiration from modernity, but also the ancient world and science fiction. So it’s a mix between tradition and the new, and futuristic influences too.

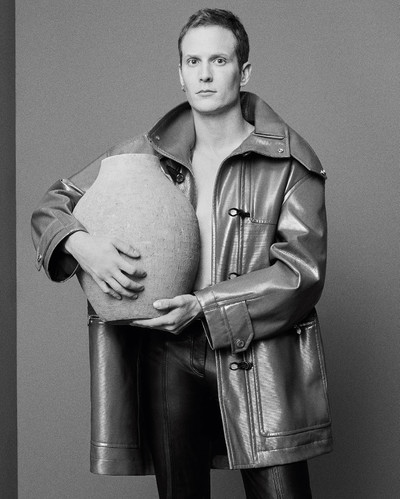

You mentioned the shoot you’ve just done for System. Tell me more about it.

My own personal experience is reflected in the shoot. It is the story of the models whom I met when I first arrived in Paris. It was a community, and for me it was the first time I saw community beyond my skin colour. So the most important thing about it is the casting, which was very challenging because the stylist Robbie Spencer is always someone who chooses the casting and the character is very important to him. But he really loved the narrative. So, he went for it. And I’m so happy that I worked with him because I really love his work

Was it the first time that you’d worked together?

Yes. For us it was a character study. Who are these people? What are their inspirations? Who are they inspired by? These people are models who are all artists, the models I’ve known since my early days in fashion.

You are such an archetypal Renaissance Man, somebody who truly embraces all modes of self-expression. Where do you want to take your practice next?

I’d love to make films. I already have precise ideas about the films I want to make which are political, but at the same time very subtle. I think my role is to help my people realise their beauty in the same way that I learned in fashion, where people helped me realise my confidence. This is why I am where I am. But I think the biggest problem with my people at the moment is the lack of confidence in themselves. This is my biggest purpose – I’d love to make movies about the intelligence of beautiful Black women and Black men, I’d love to make very romantic movies. It’s something that I haven’t seen at all, and I want to do something that people have never seen.

Talents: Alex Foxton, Adrien Dantou at Success, Henry Kitcher at Ford Models, Tom Atton Moore at Initial, Sang Woo Kim at Lumien, Clement Chabernaud at Success, Fernando Cabral at Marilyn, Félix Gesnouin at Success

Casting: DMCASTING

Hair: Eugene Souleiman at Streeters

Make-up: Celine Martin at Art + Commerce

Set designer: Félix Gesnouin at Total

Production: Casa Projects

Executive producer: Tucker Birbilis

Production manager: Florent Norcereau

Digital tech: Stefano Poli

Photography assistants: Matthieu Boutignon, Mitchell Sturm, Sofiane Vergnet

Digital tech assistant: Vittorio Poli

Styling assistants: Carolijn Hooij, Cecilia Baistrocchi

Hair assistants: Yuri Kato, Aimie Brenanan, Celine De Cruz

Make-up assistant: Thomas Kergot

Set designer assistants: El Mehdi Largo, Luc Scriberra

Production assistants: Gwen Michau, Camille Doussy

Post-production: Maria Bieluszko