Interview by Fabrice Paineau

‘Usually when someone gets their hands on AI, they get carried away with the vast possibilities. I personally want my world to feel more grounded and more in the realm of realism and photography.’

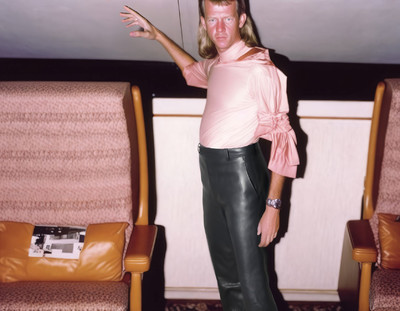

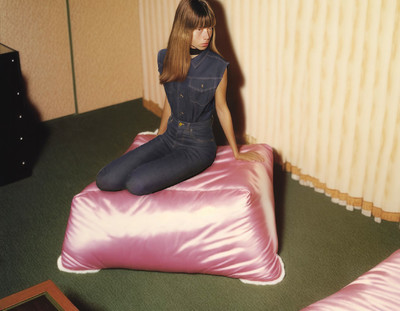

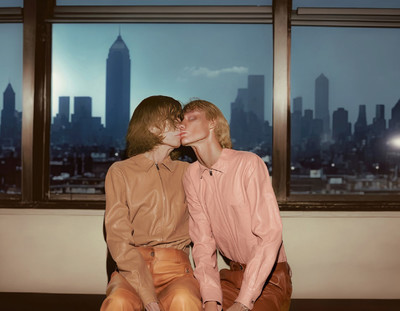

All images: Marili Andre,

Double magazine, Spring/Summer 2023.

Stylist: Lotta Volkova.

For Double magazine’s Spring/Summer 2023 issue, Greek-born, London-based photographer Marili Andre shot a fashion cover story that bucked against the limits of the medium. On the surface, through its casting, styling and attitude, the story feels rooted in raw, everyday reality. Yet the construction is precise, cinematic; uncanny, yet highly sophisticated. This tension between immediacy and tactful orchestration is at the heart of Andre’s work. In collaboration with stylist Lotta Volkova, she created a series that doesn’t just show fashion, but stages it within a world that feels both familiar and strangely hyperreal.

In the following conversation, Fabrice Paineau, editor-in-chief of Double magazine who commissioned the series, discusses with Marili Andre the references and ambitions that shaped it, her use of AI tools to help craft its execution and aesthetic, and the ways she situates herself in fashion photography today – within the restless spirit of experimentation native to the rich history of the image-making. The conversation is prefaced by Paineau’s poetic, short-form reflection on the birth of and enduring presence of photography.

‘From 1822 to 1839, Daguerre’s diorama and laboratory stood here, where he perfected Joseph Nicéphore Niépce’s invention and discovered the daguerreotype.’ These words, discreetly inscribed on a plaque, placed on the back of a building situated on Paris’ Place de la République, makes no secret of its intention: to geolocate the invention (or almost) of photography, and give it a new physicality – a plaque, a place. This is the same photography which, in its nascent years, was deemed the poor lover of its first mistress: painting. And that original fear that a single click could never replace the art of gesture and thought. It is amusing to note that contemporary art has recently reconnected with the success of increasingly figurative painting. Back to the…?

But here we are once again, two centuries later, with the hydra of artificial intelligence rearing its head and causing concern in every article about the future of photography, to the point that it’s been claimed that recent prizes at festivals have been won by works created solely using artificial intelligence!

At the dawn of these debates, photographer Marili Andre and stylist Lotta Volkova recently played with these questions in Double magazine. They insisted, in an almost secret recipe, on including a bath of artificiality in a series of fashion photographs combining historical and personal references from the photographer. A strange result for authentic intelligence.

And the essential question remains: imagination does not operate on the same terrain as intelligence. It requires natural ingredients in this new recipe. Artificiality, yes, OK. But it also needs fertile ground of taste to enjoy it. Let’s be honest: photography, however artificial it may be, never imagines the worst, except in its bad taste. Whereas the eye can enjoy it in complete freedom. Besides, where are we going to put the new plaque?

Fabrice Paineau, Paris, 2025.

‘My mother had this undying love for clothing. Her absolute obsession with matching this skirt with that jacket and those heels.’

Fabrice Paineau: What kind of background do you have artistically?

Marili Andre: I come from Crete, in the south of Greece. My mother had this undying love for clothing. Her absolute obsession with matching this skirt with that jacket and those heels. The house was practically bursting with shoes and bags. That probably does something to a child, right? There was this obscene banality I had to emerge from as a teenager. I’m still unlearning my mother’s school, although that school quite possibly also made me want to be here today. My father was a brigadier general in the army which also played a big part in my upbringing. I managed to get to London despite the anguish. They didn’t want me to go and I had to really fight for it.

My parents didn’t believe that I was going to be an artist. Their take was: ‘Right, you can go, but you’re coming right back to study something actually grounded.’ But I decided to stay anyway. I worked all kinds of jobs: from washing dishes to mopping floors and waiting tables… And then I got hired taking Polaroids for a model agency. I would shoot my own thing after hours in their small studio and I managed to build a mini portfolio very quickly, in about a year.

Eventually I quit and went freelance. I never got to assist during that period, I lacked the connections and confidence. Through the model agency position I gained an understanding of how one types a simple, yet effective email and the importance of saying ‘yes’ and ‘no’.

What was the turning point for you, from your Greek fashion references to what you’re interested in depicting today?

At my first week of university in London, a boy at the back of the class handed me a copy of Self Service – I had no idea what Self Service was. He was this boy from Pakistan called Arfan who wore a red Burberry trench coat every single day for a year straight. I believe I was 17 and I came across Inez and Vinoodh’s work. It was the Joe McKenna issue with Stella Tennant on the cover. To be introduced to that issue for the first time and to go through that was really something. From the graphic design to the fonts and I mean, coming from Greece and only having seen Vogue and then seeing that, it just…

I remember that issue, it’s one of my favourites too. So, System has asked us to discuss the shoot you did for Double with Lotta [Volkova] for the Spring/Summer 2023 issue. I remember having an initial discussion with Lotta during which I said to her, ‘Give me a surprise’ – and that shoot was a total surprise to me.

You didn’t know what you were going to receive from us at all, right?

No, but I love surprises and I trust the people I like. I still don’t know how you created the story because you didn’t want to say at the time, but I’d love to know more about it now.

Sure! The way it was done is so personal and internal, it almost feels like asking a photographer what camera they use. It’s not really about the tool. I had just started exploring the software and was deeply immersed in this new AI experience. I even set up a separate Instagram account at the time on which I’d post under a different name. Lotta then reached out introducing herself not knowing it was me – we had already collaborated multiple times – wanting to work on something together. I sent her a selfie laughing and we took it from there.

Honestly, it is one of the best portfolios I think we have ever done. It was the first time that I’d seen something that was produced using elements of AI but in a really creative way.

Not soulless, you mean? [Laughs] It really has my own imagery within it and countless hours of work – that’s why. AI was used but just as a visual command, and the visuals were all personal. I also love working with elements that resist polish. The more polish, the less I feel I can relate on a personal level. But there’s always a certain atmosphere that follows, that lifts the roughness. I think it happens subconsciously throughout my work, even on a non-AI level. There is always this constant resistance to the polish. My resistance counterbalances that perfection.

Do you see your dialogue with Lotta as mostly conceptual or visual?

With Lotta it can totally hop between the two. I remember vividly that in the very beginning of the project, there was a certain desire to ‘drive’ the medium to specific areas. However, the medium then – as much as now – offered limited control, and when Lotta and I tried to push it further, things didn’t quite work out the same. It didn’t give off the atmosphere that attracted her in the first place. We both agreed it would be best to trust the initial process, which is what we went with.

‘I found that the whole gear talk around cameras,lenses and film felt like a delay or distraction from taking the actual images.’

Where did the original idea for the shoot come from?

It all derived from one single image that I kept using as a foundation for my work. It’s a photo that I’d taken of a terrace in my family home back in Greece. The view behind is Heraklion, the city I grew up in. The image depicts this girl I scouted in the street years ago that I keep photographing every year. And it has a lighting set up that washes throughout the work. I photographed her wearing this pink satin top – satin is an element we have been conscious of, me and Lotta, and it was a blue, gloomy day. So I kept blending that image with other images that I’ve taken of other people, and I kept feeding it into the AI program. I just kept feeding it and feeding it, and then I’d look at what I was getting back, and then I would blend that image with a new photo I’d take. Then I would go and shoot some more, just to constantly blend new images with the results I was getting from the software. This experimentation kept going until hundreds of individuals were generated. Which is fascinating.

So, in a way, you were putting your own memories into the programme. With AI, ultimately it’s a question of what you do with the process.

Of course. Working with AI, I ended up realising how much power I have when it comes to casting. My AI world became very people-centred due to that. If you look closely, the worlds I create in my images are not really surreal. It’s more about the variety of the faces. Usually when someone gets their hands on AI, they get carried away with the vast possibilities. I personally want my world to feel more grounded and more in the realm of realism and photography. It initially started as pure fascination, and now it’s a tool I have acquainted myself with. Ultimately, I would say it has ended up being both a tool and a new way to just play.

Just because you’ve done some shoots using artificial intelligence, you’re not considered an ‘AI photographer’. How do you usually shoot – digital?

Yes, I shoot digital. Just before going freelance I briefly considered taking the analogue route. But apart from not being financially able to at the time, I also found that the whole gear talk around cameras, lenses and film felt like a delay or distraction from taking the actual images at the time. I did some extensive research and landed upon a digital combo and moved on with designing ideas and taking photos.

Interestingly, a lot of photographers are going back to using film. What’s your position on this?

Perhaps they have this urge to revive a certain aesthetic that feels familiar or they look up to, or just simply love the slow pace that can surround the analogue aspect of the craft.

Even though some people weren’t even born when film was being used widely.

Yes, regardless, that imagery still lives on. Before starting out, I felt incredibly drawn to the world of the Pentax and Mamiya lenses. At some point I would pop those lenses on my digital cameras and work that way, which was too much of a hustle. Eventually, I was like, ‘I’m just going to strip off all this, back to a regular set up, no longer after any sort of look.’ I just wanted to focus on what I’m actually shooting, not how I’m shooting it.

Sometimes your pictures remind me of older traditions – even the colours of someone like Joel Meyerowitz, or the feel of Kodachrome. Are those references you bring in deliberately, or do they just slip in subconsciously?

I think you’re seeing that happen subconsciously because colour fluctuates for me. I don’t think of it as a photographic identity and a huge part of my practice. It’s more about shadows and highlights. Colour can be squeezed in and out for me.

Your pictures often feel cinematic – not just the light, but there’s a kind of suspense in the poses or gestures. Do you think of film or literature when you’re putting a story together, or does that just happen naturally?

I love images but long before photo books or magazines, I rented video cassettes and DVDs. I’m drawn towards motion for images and towards attaching character to my subjects. All of that rather subconsciously, I’d say. There’s a constant need for space, textures. Once I grasp my starting point – be it a single reference image, or a T-shirt, even a piece of furniture – I can build from there.

Lastly, the cover line for that issue of Double states: ‘The splendours and miseries of the everyday lives of young (and not so young) fashion designers in 2023.’ When you saw that phrase placed over your cover image, what did it open up for you in relation to your images?

It made me think about the relentless pressures of being a fashion designer today and what the use of AI can mean for the field. Whether it adds to their pressure or whether it can take some of it off. How my story was signalling the arrival of a new era that can either feel like a gloomy cloud approaching or like a new way to play. Is it all down to how one chooses to approach it? To an extent, I think so.