Interview by Christina Donoghue

‘The challenge, of course, is that AI doesn’t yet fully grasp the codes of high fashion – the nuance of a garment’s cut, the prestige of a brand, the fantasy a fashion editorial is meant to sell.’

Since its creation in 1998, Google has not merely indexed information – it has redefined how we navigate the world. The internet has grown into an omnipresent force, shaping the way we gather news, conduct research, communicate, connect and even form romantic relationships. What began as Tim Berners-Lee’s visionary World Wide Web is now so deeply embedded into the fabric of our daily lives that the once-common phrase ‘in real life’ (meant to distinguish between the physical and the digital) has been cast aside by some in favour of the gentler ‘away from keyboard’, a term that has travelled far beyond its early gaming origins.

Given its vast cultural reach, one might expect the internet to have inspired a fully-fledged artistic movement that reflects the complexity and contradictions of our era. The Industrial Revolution found its aesthetic response in Futurism; post-war consumerism blossomed into Pop Art. Postmodernism exists, certainly, but does it truly encapsulate the here and now? That question remains open.

What’s undeniable is that the creative industries are experiencing a new kind of divide – perhaps the most striking since the birth of digital photography – brought into sharp relief by the meteoric rise of artificial intelligence. Among its many tools, ChatGPT has become indispensable to countless creatives almost overnight. Yet fashion, that eternally self-referential art form, has often sought reassurance, wisdom and provocation in its own history.

Against this backdrop, two of fashion’s most forward-thinking figures, visionary image-maker Nick Knight and pioneering stylist Simon Foxton, continue to resist nostalgia in favour of exploration. In conversation, they reflect on decades of collaboration, their unwavering pursuit of originality, and why, for them, AI is not a threat but the most intoxicatingly liberating new medium for visual expression.

Christina Donoghue: You’ve worked together for many years, yet your recent collaborations with AI seem to mark a new chapter. Am I right in thinking your recent Numéro editorial is your first truly joint project that leans so heavily on AI?

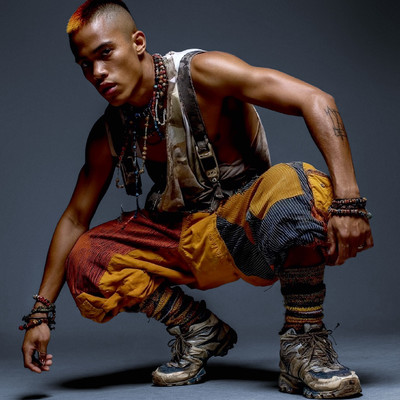

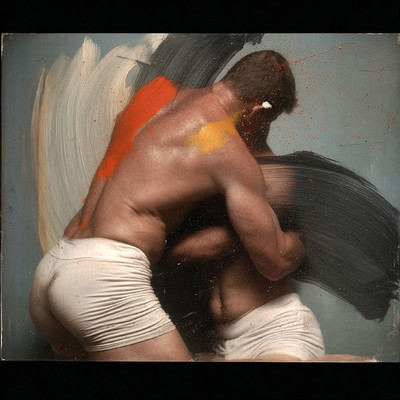

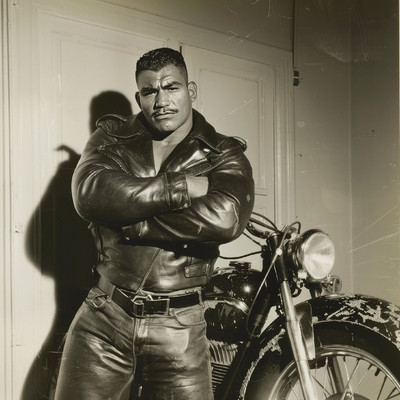

Nick Knight: It’s certainly the first major one, but not the very first. Simon created a Tom of Finland-inspired series for SHOWstudio’s SHADOW-BAN exhibition last year, and we also worked together on our G-A-Y film.

Simon Foxton: Yes, I created the AI images and Nick brought them to life by animating them and turning the stills into film by using AI. In a way, that was our first real AI collaboration, quickly followed by the Numéro story. Nick is gently trying to lure me back into fashion, but officially I’m retired.

Yet your AI work carries echoes of your early editorials with Nick. It’s as if the aesthetic DNA remains unchanged.

Simon: I think that’s inevitable. AI requires an enormous amount of curation and the images I choose are, naturally, the ones that align with my taste; a sensibility I’ve always shared with Nick. Over time, as I’ve worked exclusively with Midjourney, an AI text-to-image generator, I’ve shaped it to understand my preferences. It now produces imagery that instinctively resonates with me, so it’s no surprise that my AI work mirrors my earlier fashion styling in spirit.

‘What you see in Simon’s AI work is, at its heart, the same decision-making sensibility that has guided him throughout his career. Unmistakably his.’

There’s an art to crafting the right prompts, isn’t there?

Simon: Absolutely. It’s a balance between being precise enough to guide the AI while leaving room for unpredictability. There’s a poetry to the language you use: too rigid, and you stifle its imagination, too vague, and it loses coherence. That dance between control and

surrender is where the magic happens.

Nick: It’s entirely natural that Simon’s AI work retains his distinctive aesthetic. Our tastes may evolve. We might encounter a film, a piece of art or a sensation that shifts our perspective, but those influences rarely alter the foundation of who we are. I often liken it to the simplest decisions in life. Whether it’s chocolate or cheese, coffee or tea, your instinct knows before your mind has time to deliberate. Over time, our preferences mature, but the core remains. What you see in Simon’s AI work is, at its heart, the same decision-making sensibility that has guided him throughout his career. Unmistakably his.

What first drew you both to working with AI?

Simon: For me, it was something of a revelation. I’d known of AI for years, but as someone not naturally inclined toward technology I never imagined it would suit me. That changed a couple of years ago when my friend, the hairstylist Matt Mulhall, showed me some images he’d created on his phone, and I was instantly captivated. I downloaded Midjourney that same day and what astonished me most was its immediacy. You could conceive of an idea and see it visualised within minutes, sometimes seconds. For someone like me, who has always sought the most direct route to expression, that speed was intoxicating. After Saint Martins, I launched my own fashion label but found the process laborious. Styling offered a swifter, more fluid way to express ideas and later consultancy proved even more streamlined. But AI? It is, without doubt, the most effortless medium I’ve ever worked in.

Nick: I find it irresistibly seductive as a medium, particularly if you approach it with the same creative intent you bring to any other discipline. I’m often baffled as to why an artist wouldn’t want to explore it given its potential. Imagine being able to transform a flat image into a three-dimensional printed object, conjuring imaginary sculptures into existence. I can’t think of a single visionary, from Rodin to Man Ray, who wouldn’t seize upon that possibility to cross mediums and to experiment in ways previously impossible. For me, AI is not about replacing one’s vision, it’s about expanding it. It offers choices, much like the tools we’ve always used in more traditional workflows.

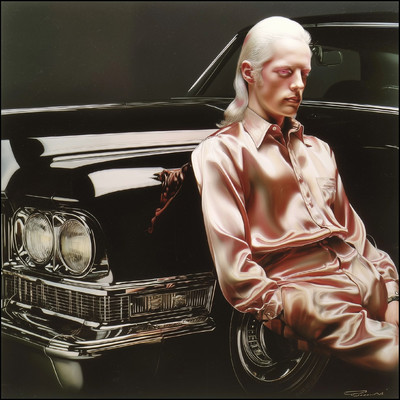

Historically we’ve compartmentalised mediums: painting, sculpture, photography, film. Crossing between them was often seen as the territory of the overly ambitious. We were taught to master just one. But AI dissolves those boundaries entirely. You can input a poem and receive an image; you can feed it an image and receive a sculpture. My own approach differs from Simon’s. I’m drawn to the abstract and often work with AI models that produce painterly, distorted imagery. Images that resemble reality no more than a Modigliani resembles a photographic

likeness. I’ll then take those surreal

results and place them into another AI, Midjourney, for instance, with the prompt to ‘rationalise the abstract.’ That’s when extraordinary things happen, things I didn’t know were possible. As an artist, I’m compelled by anything that pushes the boundaries of what’s visible and AI does exactly that. It reveals images and ideas I could not see, opening entirely new dimensions of creative possibility.

Simon: Exactly. For me, it’s perhaps the most thrilling tool I’ve ever encountered – ironically discovered only after I’d ‘retired’. In a strange twist, I feel more creatively alive now than at any other point. It’s unlocked an entire realm that had been, until now, out of reach. I understand the hesitation, the fear, the instinct to recoil from something so new, but it’s a wonderful tool. It should be embraced. It opens not just a door but an entire vault of possibilities.

Nick: For me, AI feels like the culmination of a long wait that began with the birth of the internet. A new art form truly native to the medium in which I’ve lived and worked. The internet reshaped everything when it arrived; it was a profound pivot point, offering seemingly endless horizons. Surely, it’s time it had its own art form.

Simon: You’re right. Until now, nothing has emerged that both draws from and responds to the internet quite in this way.

Simon, if I can turn to your work for a moment, you’ve often spoken of steering away from abstraction. I wanted to ask about the almost devotional realism in your images, often paired with captions on Instagram that give them an added layer of narrative.

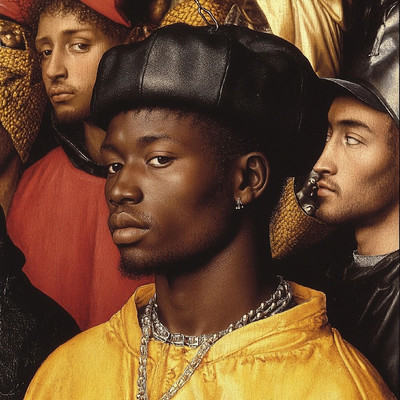

Simon: That’s deliberate. Nick gravitates toward the abstract, but I’ve been intent on making my AI work feel plausible, anchored in forms of photography I already know and love. I draw on those traditions, reinterpret them or blend them together. The goal is to make the result believable. Not because I’m trying to deceive, but because that’s the aesthetic that resonates with me. It’s just what I like.

Nick: When we worked together, one of Simon’s enduring touchstones was – and still is – National Geographic, which rarely ventured into abstraction in its imagery.

‘Prompting AI becomes a creative act itself. It’s a linguistic skill as much as a visual one, greatly enriched by a strong knowledge of art history.’

That’s something I’ve also seen reflected in your scrapbooks, Simon. They’ve long been an important part of your creative process. Collage artists, from John Stezaker to Hannah Höch, have often turned to National Geographic for source material. Do you think of AI as a kind of new-era scrapbook?

Simon: Absolutely. My process has shifted fluidly over the years, from physical scrapbooks to the Tumblr era of the early 2010s. My Tumblr was like an online scrapbook, a living archive, until it became censorial and prudish and began stripping images from people’s collections. I came off the platform in a fury thinking ‘Well, this will show them!’ I downloaded my account and thousands of images before I logged off, most of which have just been sitting around in files on my desktop. At the time, I wasn’t entirely sure why I was collecting them. When we were still shooting, they served as reference points. Now, AI has given that archive a second life. It allows me to transform those fragments into entirely new photographs.

And your Instagram captions, they’ve become something of a signature. They seem to help you flesh out this world you’re building, which is almost teetering on the edge of a convincing reality.

Simon: Well, I wanted to add some sort of context to the work I was producing. Otherwise, it was just ‘look how clever I am.’ Initially, I was amused that people believed it, and then I got to the point where I didn’t want to fool people. I didn’t want anyone coming away thinking they’ve been made to look like an idiot. I am not trying to say that they are real; I just want them to be seen as realistic.

The hyperreal plays a strong role in your recent collaboration for Numéro, doesn’t it? Could you both talk me through that?

Nick: The concept began with something that felt almost National Geographic in tone, this imagined journey across America photographing young couples in a range of social, cultural, and economic settings. I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of capturing a nation at a particular moment in time, in the way Robert Frank achieved so profoundly in The Americans. For this project, we conceived a series of 25 portraits of couples, each one distinct. Simon would use AI to create a unique, stylised garment for each pairing. The challenge, of course, is that AI doesn’t yet fully grasp the codes of high fashion – the nuance of a garment’s cut, the prestige of a brand, the fantasy a fashion editorial is meant to sell. To bridge that gap, I photographed real models posed in ways that mirrored Simon’s AI couples almost exactly. We then replaced one half of each pairing, leaving one AI figure and one real person. The casting became essential. We worked closely with the casting director Stefanie Stein and stylist Lara McGrath to ensure that each model felt convincingly in step with Simon’s AI styling, as though they truly belonged together. To put the two images together we worked with the brilliant Tom Wandrag, a digital artist from A New Plane who often works with me in AI and CGI.

Simon: I thought it was an incredibly smart way to use AI, one that didn’t replace the craft of photography, but rather worked alongside it. The integration was seamless and I think that’s why it worked so well.

What kind of prompts did you use for the series?

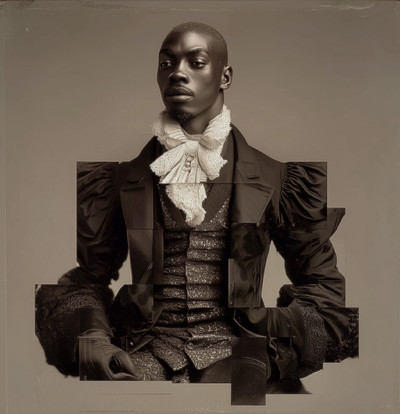

Simon: They were quite specific. One, for example, was: ‘An affluent young African American couple in a glitzy mansion. He’s standing, she’s sitting, wearing high-end clothing, photographed in the style of a National Geographic reportage.’

Nick: I tend to work less literally. I might start with something like, ‘A girl standing by a fireplace,’ then add seemingly unrelated words like ‘candle wax, honey, shoe polish, chandeliers’, just to see what the AI throws back.

Simon: Oh, absolutely. You can work that way, and I have. But for this project, we had a specific visual language in mind, so there was less room for pure improvisation.

Nick: That’s part of the artistry in AI. The prompt itself becomes a creative act. It’s a linguistic skill as much as a visual one and it’s greatly enriched by a strong knowledge of art history. If you understand what National Geographic reportage actually looks like, or you know the quiet tension of a Balthus painting, you can guide the AI towards imagery with a certain cultural and aesthetic weight which implies a certain education in the arts.

Simon: You have to draw from your own internal library of references.

Nick: Just as you would when shooting a conventional editorial. You might think back to an extraordinary exhibition of, say, FSA photography and try to reinterpret what made those images so enduring. You realise it’s not just the subject. It’s the lens choice, the camera angle, the light, the texture of the clothes, the character of the people and the reason those pictures were first taken. You pull from those established reference points, but you translate them through your own eye and for your own reason. There’s no merit in simply reproducing a Dorothea Lange photograph, for example. You create something new, something informed, as there is no joy and no satisfaction in simply reproducing an existing piece of art. Plagiarism is the most soulless, and I might add artistically unrewarding, endeavour.

Simon: Exactly. My work is steeped in references, but I’m never trying to impersonate a specific photographer or artist. I might use National Geographic as a broad stylistic umbrella, but I wouldn’t type ‘in the style of Nick Knight’. It would feel wrong. There’s no point in imitation.

Nick: Simon, do you find yourself developing a kind of relationship with your AI? Not in a sentimental sense, but do you see it as an entity in its own right?

Simon: I do, actually. I’m not talking to it over coffee, but there is a mutual recognition of sorts. Over time, it has learned my aesthetic preferences. It now anticipates my taste, becoming an extension of my own visual instincts.

Nick: In some ways, the landscape we’re working in now is an improvement on what Simon and I were accustomed to in the early years. Take, for example, a 20-page story for i-D, the magazine where we first met and which, for the first 15 or 20 years of our collaboration, was our primary platform. Back then, a single editorial might require a month of preparation, another month of shooting, and then a further month in post-production. It was an immense investment of time, energy and resources. And yet, when the work was finally published, there was almost no feedback unless someone took the trouble to send a letter to the magazine which, to be honest, never happened.

Simon: You could never be entirely certain how it was received. Even now, you see Instagram accounts that repost editorials from that era as a kind of retrospective appreciation, but at the time, there was no feedback on what you had done.

Nick: The only real measure of a story’s impact was how often it was copied. Believe me, there were plenty of derivatives. People often criticise AI for ‘stealing’ other people’s work, but the number of Simon’s stories that were appropriated – used by other brands, ripped off by other photographers – is staggering. In truth, I don’t see much difference. Our work ended up on so many mood boards. I remember meeting Rihanna for the first time and she said to me, ‘Your work is on every mood board and deck I ever get sent!’ It does make me feel very proud to hear that sort of comment, but the reason I mention it is because AI gets so much criticism for referencing other artists’ work but it has always been thus. Every trip to a gallery fills our minds with images that we subconsciously draw on when we are creating.

Simon: Now, working online, you at least get a direct sense of engagement. Likes, comments, interaction.

Nick: Exactly. Whether the response is positive or negative, it’s still a connection. In the early 20th century, the Dadaists staged performances and exhibitions where audiences would shout, heckle, even rip work from the walls. It was visceral. A real, physical reaction. Compare that to today’s online responses, perhaps less dramatic, but still an acknowledgment that your work has been seen. I’ve always believed that an artist should create first and foremost for themselves, not for their audience, but silence can be deflating. At least now, you know someone is looking.

Simon: And that matters. With the internet, you know your work is being engaged with in some way, which is far better than releasing it into a void.

‘I’m not talking to AI over coffee, but there is a mutual recognition of sorts. It’s learned my aesthetic preferences. It now anticipates my taste.’

Especially in fashion, where persistence and drive are essential. It’s much easier to keep going when there’s an audience in front of you. It pushes you forward.

Nick: It creates a conversation, however small. At SHOWstudio, we’ve always tried to involve our audience directly. In the early days, that online-to-offline connection felt incredibly close and immediate.

Simon: Working with AI has given me a similar spark to what I felt when we first began in fashion. Looking back, you realise how fortunate we were. There was little to no budget, but we had complete creative freedom. That freedom was everything. AI, in its own way, has brought that feeling back.

That reminds me of David Bowie’s line to Jeremy Paxman: ‘Where the internet is concerned, the monopolies don’t have a monopoly.’

Nick: In a way, fashion brands are killing off their own industry at the moment because the talent that was drawn to it for creative reasons, like Simon, Ray Petri or myself, loved fashion for the pure creative element of it. We would create visions and characters by pairing so many different items of clothing together, referencing everything from film to art to the everyday people we saw on the street. You can’t do that anymore because the brands are now insisting you can only use their clothing as a full look from their collection; it’s turning what used to be pure, unbridled creativity and the very reason we loved magazines, into an unpaid advertising campaign

slapped in the middle of a magazine.

Simon: If I were starting today, I’m not sure I’d choose styling at all. It’s no longer the same creative avenue it once was. I do wonder whether AI might, before long, take over certain roles entirely. Lookbooks, catalogues, that sort of thing. They don’t want creativity in those kinds of roles.

Nick: Possibly, but I think AI is still in its infancy. It’s busy imitating – photography, film, painting – without quite grasping that it is its own medium. This has happened before. When photography emerged, it desperately sought artistic validation through mimicry of painting.

Simon: Exactly. It dressed itself in painting’s clothes, quite literally.

Nick: Yes. Early practitioners brushed light-sensitive emulsions onto glass plates as painters brushed pigment on canvas. They posed like painters, too. There’s that portrait of Edward Steichen in a smock, holding what looks like a palette. Anne Brigman painted clouds into her images using graphite powder. All to persuade a sceptical world that photography was a real art, not merely an optical mechanical device unable to create the true human beauty a painter could. The same doubts are now being cast at AI. But, just as photography eventually found its voice around the 1930s, when it stopped imitating painting and embraced its own strengths. I think AI will reach that point of self-definition.

Simon: Exactly, I think you’re right. AI hasn’t got into its stride yet, and it hasn’t found what it is. It has its own aesthetic, and I think a whole new type of art is coming out because of it.

Nick: And it will be inherently cross-disciplinary. There are already tools that can turn an image into a poem. This is where boundaries begin to dissolve.

Simon: Which brings us to the inevitable question: what becomes of the photographer? Is the role itself endangered?

Nick: I’ve been saying photography is dead since the middle of the 1990s. Not just to rub people the wrong way but to make them think, by trying to justify why they think it’s still alive. Photography was defined by a very clear set of parameters, and when you move all those parameters, it becomes a different medium. You can link the work of early photographers such as Eadweard Muybridge to modern photographers such as [Robert] Mapplethorpe, as they all work within the parameters that defined the medium. What we do now exists way outside of those parameters. So, when digital photography came along in the mid-1990s, you could do things with it you couldn’t do with conventional photography. I can now take my phone and take an image that is instantly sent to a global audience, on a backlit screen, or I can turn the still image into a film or even a 3D object! That is so far from photography as to make it clear we work in a new medium entirely. The idea that I am a photographer or that photography is still the dominant art form I use is spurious to the point of mendacity. It’s not. I’m surrounded by objects that I’ve printed out. It’s all interesting and incredibly exciting, but none of it is best described as photography. I don’t think photography has a way forward. Even iPhone photography is separate from the traditional medium because it uses AI. AI is built into your phone camera and is part of how the world now creates imagery. Every picture you have taken on your phone has been in part created by AI. I have studied photography for all my life and still feel incredibly affectionate towards it as a medium but as much as I love it, in all its forms – from Anne Brigman to my contemporaries today – and as much as it still makes my heart beat faster, I would be dishonest to myself, and to anyone who was reading my words right now, to say that what I do is photography.

‘I do wonder whether AI might take over certain roles entirely. Lookbooks, catalogues, that sort of thing. Brands don’t want creativity in those roles.’

Simon: Do you think photography and AI can coexist?

Nick: Coexist, perhaps. But the leap AI represents is far greater than the leap from painting to photography. This is a transformation on the scale of the Industrial Revolution, or the invention of writing itself. We stand somewhere humanity has never stood before, in art or in communication. And, as with all evolution, something will come after us. Perhaps that ‘something’ will not be carbon-based. Whether that’s better or worse is a question for history, but AI will be central to it.

Nick: It’s worth remembering: we ourselves supplanted earlier forms of humankind. Evolution is often indifferent to sentiment. That’s not to say I’m campaigning for our extinction in favour of a silicon species, it’s just that the definition of ‘humanity’ may not be as fixed as we like to think.

Simon: I suspect you’re right.

Nick: If we pan back, there’s a larger shift unfolding. Capitalism, in its current form, is revealing its hollowness; socialism and communism, as they’ve been practised, are equally ill-fitting. Add to that the stark realities of climate change, existential threats pressing from all sides, and it’s clear we need more than incremental adjustment. We need a different rhythm, a reimagined social proposal. I don’t yet know what that will look like. But I do know that evolution doesn’t pause, and we’ve never reached some ultimate pinnacle, no matter how much we flatter ourselves otherwise. We will evolve. The question, almost absurd, but worth asking, is whether we might one day become a silicone-based life form rather than carbon-based. Whatever follows us – and something will – will be shaped by AI’s development. That future could be one where cancer, ageing, even poverty, are within reach of eradication. Where someone without means can access legal defence, or 3D-print a home. For centuries, justice and opportunity have been rationed according to wealth; if AI can redress that imbalance, then we have to ask: is that ‘evolution’ worth embracing? The central proposal we have to think about is, which part of AI do we wish to keep, if any of it – the part that can save your child from dreadful diseases such as cancer but we lose the part that can change how we take an image?

Simon: It’s a difficult question, because what you’re really describing is a post-photography world. In fact, a post-work world. Which leads naturally to the question: are jobs even necessary? And beyond that, the deeper question: what is our role, our purpose? Many of us draw identity and joy from work, particularly in the creative fields. But could we reach a point where machines decide we’re surplus to requirements? That human life, in fact, is the contaminant?

Nick: We wouldn’t be the first human iteration to disappear. We supplanted earlier forms of humankind ourselves, the Dryopithecus, Ramapithecus, Australopithecus, Homo habilis, Homo erectus, Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, for example were all replaced by our own evolution to becoming modern humans.

Simon: So you’re saying the robots are coming?

Nick: The problem is, the moment you say that, it summons every tired sci-fi cliché. Silver humanoids, flickering warning lights, the inevitable showdown. It’s difficult to see clearly past those cultural fictions.

Like a 1970s dystopian vision of the year 2025.

Nick: Precisely. I’m not advocating for humanity’s replacement by some gleaming, silicone-based successor. But if that’s the course events take, then that’s what will happen. I believe, ultimately, life tends toward the positive, even if the path feels skewed. The internet, for all its flaws, has knitted the world together in ways that would have been impossible before.

‘The leap AI represents is far greater than the leap from painting to photography. It’s a transformation on the scale of the Industrial Revolution.’

Then what of creativity in this new landscape? Will it wither, or flourish?

Simon: More than survive, I think it will flourish. Personally, I feel more creatively alive than ever. AI feels like discovering an entirely new wing in a house you thought you knew intimately. It’s a tool that invites invention, and that is a rare and exhilarating thing.

Nick: People don’t like change because it’s threatening. The future is always uncertain, and therefore it’s threatening. You can only imagine how two farmers might have felt in the middle of the Industrial Revolution. No one knows what is going to happen, and so we can’t judge the worth of it; all we can do is react instinctively to stuff.

Simon: There’s another possibility, perhaps more plausible than we care to admit, that we may simply become avatars: entities that look and sound like us, but are no longer physically us.

Nick: Which is ironic, because we speak as though we truly understand ourselves. When in truth, we don’t. Our grasp of who we are is astonishingly shallow. If we can’t even fully comprehend our present – things like telepathy, intuition, the subtle sensory range of human experience – how can we hope to construct accurate visions of the future? Our theories are built on foundations we barely understand.

Simon: Do you think AI could help us understand ourselves better?

Nick: I do.

Simon: To propose another idea, there is also the possibility that we’re about to have so much more time on our hands. AI will be doing everything for us, and that means we’ll have more time to be present in the physical rather than the virtual. On a side note, I was at the Central Saint Martins degree show recently, and I was struck by the message that was coming across, which was a rejection of the virtual and the digital, and it was about being in the here and now. It was about the physicality of the clothes and the workmanship that had gone into them. It was about the theatrics of experiencing life in front of you rather than on Instagram. There was something quite life-affirming about it. I thought, ‘Well, maybe these students are seeing what’s coming next,’ and it’s about real life as much as the next stage of the internet. So you can have AI and the digital and everything as part of your world, but we can’t deny that there’s an innate human, not just desire but need for something actual as well.

Nick: I think we’ll live in both realms. We already juggle an ‘offline’ self and an ‘online’ self; it’s just that the line between them will blur further as digital avatars and other virtual extensions of ourselves become commonplace.

Simon: I think we’re going to look back on this period we’re in and think how humorous and primitive we’re all being because we are just dipping our toe into the water. We don’t realise the tidal wave that’s coming.

Nick: Part of the difficulty is that our imagination of the future is constrained by specific references from the past. Most of them are wildly off-mark: Terminator, 2001: A Space Odyssey – HAL 9000 coldly locking humans out of the spacecraft in the name of efficiency. We’re working with a limited archive of bad predictions. Alvin Toffler’s The Third Wave is one of the more interesting exceptions; he foresaw big cities hollowing out as people chose to stay home. If AI means we no longer have to march into offices and uphold a hundred-year-old capitalist routine, perhaps we’ll be freer. Able to live fuller, richer lives.

Simon: Which makes you wonder: what purpose will town centres serve? Many already feel like relics, existing only because we haven’t reimagined them yet.

Nick: And then populism steps in. Politicians evoke some rose-tinted version of the past – full high streets, bustling communities – to rally against whatever they dislike in the present, whether it’s AI or immigration. They ignore that those ‘golden days’ were often neither golden nor desirable to revive, and in doing so, they deny the genuine benefits we’ve gained. It’s the populist sleight of hand: a seductive fiction that serves no one but themselves.

‘There’s another plausible possibility, that we may simply become avatars: entities that look and sound just like us, but are no longer physically us.’

Do you think AI will find its way into politics?

Simon: Inevitably. It will touch every facet of life; there’s no way around it.

Nick: Which is why we have to be honest about its potential. If AI can cure cancer, surely we owe it to those who’ve suffered to pursue it. If it can secure legal representation for the poor, build affordable housing, or help avert ecological catastrophe, shouldn’t we see where it can take us? Yes, it may raise difficult questions about authorship, about jobs, but those debates shouldn’t blind us to its possibilities.

Simon: And in any case, it’s not going away. We might as well learn how to work with it.