Interviews by Neville Wakefield

Portrait by Drew Jarrett

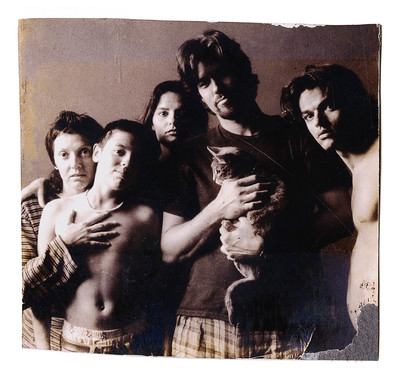

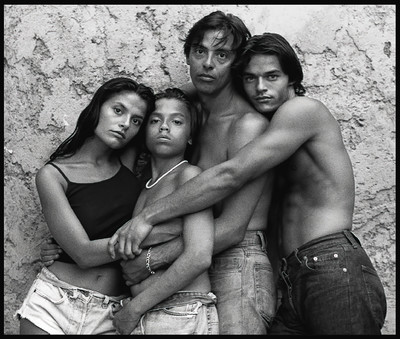

Francesca, Mario, Vanina and Gray.

The photographic dynasty that spans three generations.

From left to right: Gray, Vanina, Francesca and Mario.

I moved from London to New York in the early 1990s, a time when rent was still cheap, drugs plentiful and untamed creative energy seemed to be shaping every aspect of art, architecture, society and fashion. The young photographer Mario Sorrenti was living in a loft in downtown Tribeca. Between the darkroom and the street, skating, graffiti, art and fashion, his was a world shaped as much in life as in its image. His photographs of then-girlfriend Kate Moss became the defining moment of an era. Raw and tender, vulnerable and defiant, they brought the tight-knit intimacy of extended family to the photographic stage. Passing in and out of this world were his mother Francesca, her boyfriend Steve [Sutton], Mario’s younger brother Davide (who tragically passed away in 1997 at the age of 20) and sister Vanina. The feeling was of a family – one which had its roots in Naples but had been transplanted to New York – in constant dialogue with itself. Photography was the shared prism through which relationships to art, fashion, each other and the outside world were refracted across spectrums of interest. Mood and tonality were particular to each but there was also a common language united by a shared belief in the transformative power of the image and the sentient potential of fashion.

Now, with the additional voice of Mario’s daughter Gray – herself one of fashion’s fastest-rising image-making talents – the family conversation spans three generations and a range of experience from more than half a century. Reflecting on a world that began downtown with Francesca in Max’s Kansas City alongside the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Andy Warhol, and continues to this day in Harlem with Gray documenting the bike life scene, I’m struck by how much more than a photography dynasty the Sorrentis represent. Thirty years on, for me and so many others like me, the impression they have left and continue to leave is an indelible part of everything New York. Finally, and gratefully, I feel old.

Neville Wakefield

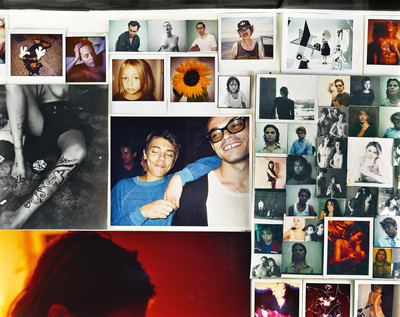

Davide and Mario (centre), surrounded by family and friends.

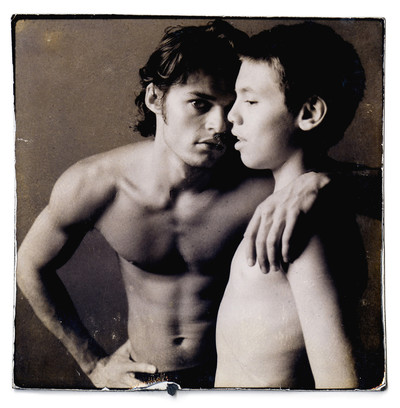

From Mario’s 2013 book Draw Blood for Proof.

‘Let’s admit it: we are a family of voyeurs.

Curiosity is part of our nature, it’s in our DNA.’

Francesca Sorrenti in conversation

Neville Wakefield: So, everyone wants to know the origin story of the Sorrentis – this photographic dynasty that now spans three generations.

Francesca Sorrenti: After high school I ran away to Manhattan from Queens and started working in a club called The Scene. It was like a revolving door of bands coming in from London and LA. It was wild, and I became friends with people like Jimi Hendrix. Later on, the scene moved to Max’s Kansas City, which became more of a fashion scene – Donna Jordan, Andy Warhol, Karl Lagerfeld and others. Back then the circles were much smaller; it was a different world living in New York, no cell phones, no social media. Even the city itself was different – there was no SoHo, no Chelsea. In 1971 I married in New York and moved to Italy, and my Italian life began. I had moved to Italy in the middle of a recession so figuring out where and how to work took a lot of creativity. Italy had its own energy, but I also carried my American background with me, especially growing up in New York.

My children grew up in a household that was both creative and social. Their father was an artist and I was always making things – jewellery, shoes, you name it. In 1973, I began working for Fiorucci which opened the doors to travelling throughout Europe and New York. At the time I had Mario and Vanina and made sure to take them along whenever I could. Summers in Italy were a world apart from life in New York. We spent entire seasons in Positano, Capri, Ischia – days filled with boating in the sea. That landscape, its beauty, rhythm and light, nourished the imagination and left a lasting mark on the creative spirit.

With everything you’ve done, how come you’ve never been in the limelight?

The truth is I never liked the limelight, and by limelight I mean posing for photos, being outlandish, hanging out with the crowd into the wee hours of the morning. By the time I was 26, I already had three children. To be in the limelight, there are certain things you had to be a part of. My head wasn’t there, plus I always shied away from the camera.

When did you return to New York?

When I separated, I moved back with my children. Those first months were brutal, basically a year of sacrifice, barely holding things together in Manhattan. But out of that struggle came a turning point. By 1983 I became a stylist and my career took off. I don’t think my career was by chance, it was rooted in what Italy had given me. Being brought up in an atmosphere like Italy, where everybody looks fabulous, especially in that era. You have to understand that there were no blue jeans, no stretch pants; you walked out of the house wearing make-up and clothes. Going back to my childhood: the pony jackets, the poodle skirts, the girls that I’d see on the street. My mother’s wardrobe… when she punished me and locked me in her closet, I was in seventh heaven.

People back then were fully armoured. Fully dressed.

Yes, they really were. And so I had an eye for detail, a deep sense of style and, of course, the resilience to carve my own path. Then I met Steve Sutton, my partner of 40 years, and an amazing stepfather. Our paths in 1984 became one, along with our careers. We rented a studio next door to our apartment and my children were always welcome. Being the Italian that I am, my children were always allowed in the studio no matter what I was doing. They hung out there, they watched TV there. I ran home, cooked dinner, we had this family life. Then at the same time, I had a very active social life. I was out every night. This was the 1980s, it was a fabulous time. In fact, people sometimes ask me, ‘What was the best time in history in your seven decades?’ I’d have to say the 1980s. I mean the 1960s were fabulous, but every decade had its own thing. The 1980s was a combo of everything. You could be a hippie. You could be a punk rocker. You could be a disco queen, you know? There was New Wave, there was disco, you could have pointy hair or a side ponytail and wear glitter. Nothing cost the way it does today. Everything was at a reasonable price. If you worked, you could afford things. I mean it wasn’t like the 1960s or the 1970s, but everything was affordable to a certain extent. One of the places I lived in was a four-bedroom apartment in the Zeckendorf [Towers residential building] with a pool and health club and everything. It was huge, overlooking the park and cost $4000 a month. Now that’s unheard of.

‘You have to understand, in Italy in the 1970s, there were no blue jeans, no stretch pants; you walked out of the house wearing make-up and clothes.’

Your children speak so amazingly of being brought up in this polyvalent creative environment where styling, photography, modelling was all part of one process. What went on behind the camera and what went on in front of it were connected in some way…

At the time we started an in-house ad agency for a clothing company. I became the creative director and Steve started shooting; he became a successful photographer shooting children’s wear. My children were always in and out even when we were working. They were a part of everything and saw everything. Being very creative, they were like three young sponges. They were also very sought after models with Ford modelling agency. Mario was the Ralph Lauren muse, Vanina for Norma Kamali and Dave for EJ Gitano. Of course, children’s modelling was very low-key back then, not to mention that I styled most of their shoots. No matter what the rhythm, family came first.

So how did you eventually get into taking photographs?

Unfortunately the 1990s brought the recession and times became difficult. Mario, who was modelling at the time, discovered photography and became very passionate about it, and Steve set up the dark room for him in our studio. I was still trying to figure out what to do. While Mario was still in the testing stage he said to me, ‘Mom why don’t you pick up a camera? You’re always telling other people what to do.’ And I replied, ‘You don’t just pick up a camera and if I were to pick up a camera I would need to know everything, and I’m not a technical person.’ And he said, ‘It’s like cooking.’ He said, and I’ll never forget this: ‘It’s like making pasta.’ Now you have to understand, back then it was all about turning knobs. He was saying, you know, ‘You turn the knob just like when you’re putting salt in the pasta.’ So one day I said to Steve: ‘Can you set up the studio? I want to try this out.’ I was so thrilled by the outcome and I found a new career, but most of all a new passion, specifically for fashion photography.

How were those first years of taking photos?

As a woman photographer at the time I felt the weight of how difficult the industry could be. There were doors that stayed shut, opportunities handed more easily to men. I was lucky. I pushed my way in and made myself a player. I shot for i-D, Interview Magazine, Vogue and did my share of advertising. Those chances didn’t come because the world was generous; they came because I knew how to navigate, because I refused to let myself be overlooked and because I believed in my talent and my style. I’ve always tried to pass on to my children that talent is the start; passion, persistence and presence matter just as much. The New York scene in the 1990s was very different. Another youth boom was starting to form with grunge exploding out of Seattle with bands like Nirvana, Pearl Jam and others bringing flannel shirts, ripped jeans, and other anti-glamour attitudes. Doc Martens and sneakers were the way to go. Hip-hop became mainstream, Tupac, Biggie, Lauryn Hill. Gangsta and graffiti were, as my kids would say, ‘the bomb’. And then the drug culture started to grow. At the time I was at the height of my career. I socialised and went to parties almost every night, but I also had boundaries. You’d understand if you lived through the 1990s. When I felt things veering in the wrong direction, I went home. I was fortunate to be that way. Maybe it was fear, maybe it was instinct, but I always remembered that I had kids.

‘My children were sought-after models with Ford agency: Mario was the Ralph Lauren muse, Vanina for Norma Kamali and Dave for EJ Gitano.’

I’m wondering, do you feel that the Sorrentis all have a shared sensibility in their work?

Let’s admit it: we are a family of voyeurs. Curiosity is part of our nature, it’s in our DNA. On an astrological level, we are a household of water signs. Mario and I are both Scorpios. Vanina and Steve, Pisces, and Davide a Cancer. We lived in a floating house. In Italy I had an astrologer do their charts. Mario was only seven at the time, she looked at me and said: ‘This child will be exceptional, he will grow into an exceptional man.’ I remember nodding, thinking: ‘Well he’s only seven, we’ll see.’ But as the years passed, I began to see exactly what she meant. His intensity, his vision, his drive, all of it was there from the start. I always found his photography very personal, very him. There always was a certain sensuality in his pictures. And then there is my daughter Vanina. She has always been my Alice in Wonderland, in a world of endless imagination, beauty and curiosity. She has this way of looking at life with a kind of eternal youth, as if she’s untouched by time. That perspective is a gift. She remains so deeply, and naturally talented. I find her pictures magical and her personal work reminds me of pictures I’ve seen in museums. Vanina’s creativity is different from Mario’s, less about drive and more about spirit. Her passion for the arts has always been deep-rooted. Where he charges forward with intensity, she drifts through ideas with grace finding wonder in details others might miss.

And obviously for Gray as well, another female perspective.

Gray, my beautiful and talented granddaughter. Her energy is beyond, but I have to say she reminds me so much of myself when I was young. Her photography is so full of energy and beauty. I also find that she’s inherited many of Davide’s traits – they have a similar character and expression. A little bit of homegirl, not afraid of saying what she thinks. Even though Gray never got to know Davide, she is very much tied to the memory of her uncle.

Can we talk a little more about Davide?

Davide, ‘Dave’, my youngest. Dave was like a sponge, he observed all the best qualities of his family and made it work for him. He loved to watch us shoot and he was gifted with an amazing sense of style. On a technical level he knew exactly how to print his photos with Steve. A truly creative artistic soul in a homeboy body. Sometimes I thought he was otherworldly. He refused to speak English properly. Everything was: ‘Yo man, hi shorty, what’s up!’ He lived with his camera by his side shooting his friends and the people and things he loved around him. He didn’t follow the rules. If he wanted to meet someone, he would just go work his way into an ad agency and ask to speak to an art director and he would actually get in! In 2018, a documentary on his life, See Know Evil by Charlie Curran was an instant success being seen around the world. DOC NYC had to add two additional showings due to the overwhelming request for tickets. It toured England, the Torino Film Festival and other venues. I was so surprised how popular Dave’s work was amongst the younger generation. In 2020, IDEA Books printed ArgueSKE 1994-1997. At the book signing the crowd was overwhelming, and again I was surprised by the number of young people who were buying his book. It sold out within a few days. Now there are three books of Dave’s work and a fourth one – on his journals – coming out. There have also been exhibitions that have been viewed by thousands of people.

How does it feel to see generations of your family all walk similar creative paths, finding their voices as they do so?

I must say I am very proud of my family. We have all been gifted with an amazing talent and love of creativity. My grandson Arsun, an exceptional musician with his own personal style, and my granddaughter Lennon, a true beauty, modelling at the moment, with inspirations of writing and directing. My amazing daughter-in-law Mary Frey, a truly gifted sculptor. When you have so much talent around you, how can you not feel blessed.

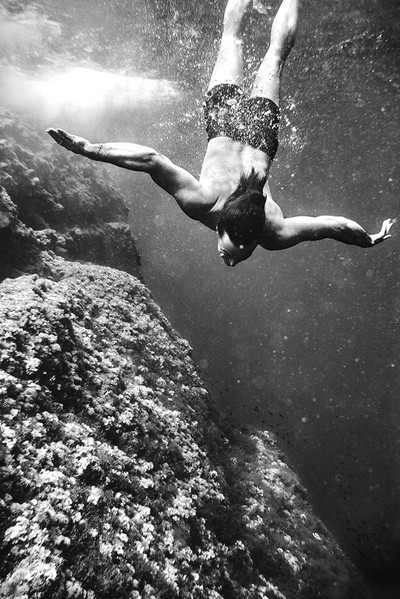

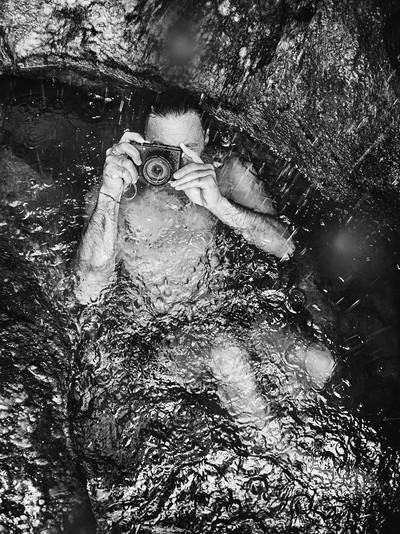

Mario photographed by Gray.

Mallorca, August 2018.

For La Mer ‘The Edge of the Sea by Sorrenti’ 2019 campaign.

‘Something happened in the darkroom that night

when I saw the images appear in the developing tray.

I was like, ‘Wow, this is pretty fucking cool.’’

Mario Sorrenti in conversation

Neville Wakefield: It is pretty unique that you have three generations where multiple family members have been at the forefront of photography and fashion. I can’t think of other examples.

Mario Sorrenti: It’s purely by accident. You know, it’s really not anything planned by any of us. The only connection that I can see is that, for some reason, we’re a very visual family. I grew up in an artistic family. My dad’s a painter, my mom has always been in a creative situation, but more of the businesswoman in the family. She cracks the whip! My dad was really about art and love and coffee, cigarettes, and just chilling. An idealistic, beautiful life.

And he was doing that in Naples, right?

Yeah. He still lives there. We all grew up in Naples, and it’s where my mom and my dad met. My mom was born in America. My grandmother Maria met an American soldier in Naples, and they got married. She went to America with him, and my mom was born there. About a year or two later, they divorced. Then my grandmother left and came back to Italy. My grandmother had a house in America and she also had a house in Italy. She went back and forth all the time, and she did a lot of business. She was kind of a crazy, cool saleswoman. She would buy garments and eyewear in Italy and bring them to America and sell them literally out of a suitcase to her friends up in the Catskills and in New York and Brooklyn. And then she would buy all the stuff in America and bring it back to Italy and sell it in Naples and Ischia. That was my childhood growing up. I remember my grandmother always with these massive suitcases going back and forth between New York and Naples.

As much as family might have shaped your approach to work, location has as well. I think about New York and about when we met in the early 1990s. I’m curious about how much the place has also helped form your sensibility.

Well, we came to New York because my mom and my dad separated. My mom decided to move back to America, and she took all of us to New York. I remember getting there in 1980 and thinking to myself, ‘Wow, this is not that bad, this city is not that dangerous,’ you know, in comparison to Naples.

I arrived in the early 1990s, and was like: this is fucking terrifying, and brilliant.

My mom was on her own, so I really grew up in New York, on the streets. I didn’t speak English, and I was thrown into street culture. All my friends were about hip-hop, graffiti, and skateboarding. I was in love with all of that. And in a strange way, when I was growing up in Naples, because my grandmother kept on bringing this stuff from America, I kept on getting these glimpses of American culture. You know, just American candy, movies, and I had a skateboard when nobody had a skateboard in Naples. I had an American passport too, which was weird because I knew nothing about America. So for me, it was like, ‘Wow, this is incredible,’ and that is the environment that I grew up in. I mean, photography really entered my life purely by accident. Nobody was taking pictures in my family at that time. When we moved to New York my mom started working in fashion…

Not with a camera.

Not with a camera, no. Back in the 1970s, when we lived in Italy, she was working for Fiorucci. She was working on jeans and jewellery and stuff like that. I think a lot of her friends were in fashion. She knew Donna Jordan and all the models from that period. She knew the whole Andy Warhol crowd. So she had those influences. When she came back to New York, she decided she wanted to be a stylist. So after a few years of us being in New York, she finally started working. I mean, she’ll tell you her story better than me. Then she started working for some TV shows and for a jeans brand called EJ Gitano in New York. And she started doing lots of kids’ stuff. And then she met Steve. She was styling and then she got Steve into taking the pictures for the EJ Gitano brand for the catalogues. Steve had just finished film school. He was 24 years old when they met. That was my first exposure to photography, seeing Steve taking pictures for the kids catalogues with my mom. They became very successful and then they started an ad agency together where they would design the catalogues. I did odd jobs around the office, like making photocopies, sweeping the floor… My mom would get me to do graffiti sometimes for the catalogues. It was fun but I was like, ‘Man, I don’t want anything to do with that commercial world.’ I just really wanted to be an artist; to paint and make sculptures.

‘My mom was on her own, so I really grew up in New York, on the streets. I didn’t speak English, and I was thrown into street culture.’

So who first put a camera in your hands?

My dad was coming to New York every once in a while to see us, and he became friends with these two Italian girls who were studying photography. They were going to ICP [International Center of Photography] and had an amazing loft on Broadway. One night, my dad brought me to a dinner party at their place; we were all messing around, taking pictures with their camera, and they said, ‘Let’s develop the film.’ There was a darkroom in the loft, so they developed the film, and started printing the pictures. Something happened in the darkroom that night when I saw the images appear in the developing tray. I was like, ‘Wow, this is fucking cool.’

A bit of alchemic magic, being in the darkroom with a couple of older girls. Anything can happen.

[Laughs] Yeah, I can see myself doing this for the rest of my life! But what was cool is that they had a bookshelf of photography books that I had no idea about – Robert Frank, Larry Clark, Bruce Weber, Irving Penn. All of a sudden I was looking at all of these images and I had never thought about photography in that way before. I was 18 and wanted to be a painter. I wanted to go to school for sculpture, my life had to be about art. I was living with my girlfriend and I’d been working on an oil painting for months. All of a sudden I realised that in one night I’d made a photograph, and something just clicked. I became friends with the girls and I asked if I could borrow their camera and take pictures and use their darkroom. They were so sweet and kind. After a couple of weeks, I started crashing on their couch and using the darkroom. For about six months, I pretty much lived in the darkroom, took pictures and studied the photobooks. And as soon as I could afford it, I bought my own camera.

When I got to New York, you were taking photos all the time. I remember you going on road trips, taking acid, and coming back with these documentary photographs.

I was just documenting and learning how to use the camera; photographing friends and whatever I could get myself into. My influences were Diane Arbus, Larry Clark, Robert Frank…

You were looking for extreme situations and road trips, stuff on the fringes.

To be honest with you, because I grew up in New York City, I grew up in extreme situations. So for me, it wasn’t that foreign. I grew up in the subway tunnels, writing graffiti and running from the cops. Getting into all sorts of trouble, and being in a situation where I might be in a little scrap was not such a big deal. I knew that’s where the excitement was, and that’s what I wanted to document, because that’s what excited me in the books that I was looking at.

Was there a sort of ‘decisive moment’ in which you realised that this could work in the context of fashion?

Because of my early years, studying classical painting and being inspired by painters like Michelangelo and going to churches, looking at sculptures, I naturally had a love for the classical nude, anatomy, plasticity and perspective of things. Also the drama and tragedy in the works really moved me. And in some weird way, I would recognise these influences in some of those documentary photographs as well. I’d see that Larry Clark picture of the boy reaching out with his arm, and it reminded me of something from a classical painting. And then as I needed to make some money, I started modelling, which brought me closer to fashion photography, and working with photographers like Bruce Weber and Steven Meisel. Seeing them work was such a huge inspiration, which gave me a new appreciation for fashion photography. These two worlds were joining and meeting. I realised that fashion and art could co-exist. I started taking some fashion pictures to try and make some money. I was taking portfolio pictures for models and for people I knew. I was finding my inspirations by documenting the street and from these road trips I’d go on; I would work on these personal projects making photographs with the intention of making a book, and then when I’d come back I’d end up in a studio shooting fashion. The road trip experiences influenced my fashion images, and it was like a combination of the paintings and the documentary work. Then photography started to change for me because it wasn’t so much about the decisive moment and just documenting anymore, it started being more about constructing a photograph, more like painting.

Growing up in Naples surrounded by these highly charged religious and classical paintings, was that something that influenced you?

That was a huge influence on me.

There’s an emotional intensity to your work, which is pretty unique. And I was curious whether it was connected to that tradition.

When I moved to London in the early 1990s and I was taking pictures there I was only 19 years old. I met David Sims, I met Glen [Luchford], I met Corinne [Day]. What I found really inspiring about them is that they were all making pictures from their life experiences. It really reflected their cultural experience. They were not only taking pictures, but thinking about what they were going to take pictures of. So I started asking myself ‘What am I going to take pictures of? What are my influences?’ So, I dove into those classical paintings even more because I was like: this is where I should be drawing my inspiration from because this is my education, my stuff, you know.

Was there a point at which you became aware that the world that you were photographing and inhabiting had become the fashion world?

You know, I was quite young and I had a lot of trouble being a fashion photographer. It was almost like being a sellout. I was constantly fighting with myself between the art work and the fashion work. I was really conflicted by all of this, but I was very successful as a fashion photographer. As much as I fought it off, it kept pulling me back in. And then my brother passed away, and that was a huge life lesson for me.

He was making photographs as well, in a slightly different way.

Yes, he started making photographs as well. My brother and I were very, very close. Not only me and my brother, but me and my brother and my sister, because we grew up in New York together on our own. Our single mom had to work all the time so the three of us are extremely close because we had to take care of each other. My brother started taking pictures because I was taking pictures and he thought it was cool like most younger siblings would.

A way to relate to the world.

Exactly. And we loved each other. So we were inspired by each other. He was inspired by my life and what I was doing. I moved to London, and then when I came back, he was taking pictures. He was pretty young and I thought, ‘Wow, this is so great.’ Davide saw the world in a very particular way. Growing up with his illness [thalassemia], his life was very different from most other kids. He had a deep emotional relationship with life. I think being so close to death gave him both the urgency and desire to live life to the fullest, to express himself, and to experience beauty and love. That sensitivity and compassion gave his work such depth. His family and friends were a huge catalyst for his work. And as for Vanina, at this point, she hadn’t started taking pictures yet. She was going to film school in LA and wanted to act.

‘I think being so close to death gave Davide both the urgency and desire to live life to the fullest, to express himself, and to experience beauty and love.’

Do you think that there’s an essential Sorrenti sensibility that crosses across your family?

Yeah, I think there is a Sorrenti sensibility. If you look at all the work, you definitely get a singular feeling.

Could you describe that?

Ouff! [Laughs] I think we’re all passionate, emotional individuals but very closely connected. I’m thinking about Gray’s pictures as well, because they’re the latest manifestation of this thing. There is a lot in her work that reminds me of my work. But in her own way. She’s very young, she is so instinctive. The thing about her that I find incredible, besides her natural creative ability to see and compose images, is that she’s a big people person. She’s super social. She’s just infectious, so everyone really falls for her, and I see that coming out in her photographs. That’s her own thing. Then there’s obviously the influence of the lighting and stuff because she sees my work. She’s inspired by the things that I’ve done. She grew up on my sets.

She’s been schooled in the Sorrenti style.

She has. Mary and I raised our kids in a way that we were always together, working and travelling. And Mary and I were young as well, so in a way we all grew up together. My mom takes pictures as well: she approached photography a little differently. She came at it more from a stylistic point of view, I think. She’s telling a bit of her own story in her photographs – growing up between New York and Naples, and this back and forth. But her focus is always more about style, it’s about the girl and the style.

Is that a distinction that you’d make between form and content? Between style and fashion photography…

That exists all the time together. But it’s about what has more weight in a photograph, and I think her photographs tend to lean more on the stylistic. Whereas Gray’s pictures, for me, lean more on the relationship between the subject and the photographer. Vanina tends to really explore the idea of being an artist as a woman, and what femininity is.

Finally, what would your advice to a younger photographer be today?

I’d say don’t compromise when you’re younger because you’ll be made to compromise later in life. And at some point later on, you’re going to have to learn how to be somebody who can be part of the solution as opposed to being part of the problem.

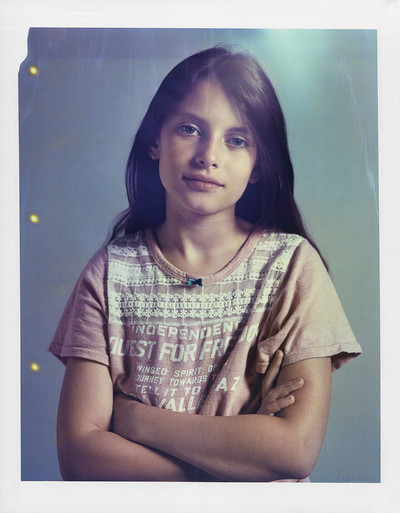

Vanina self-portrait.

8x10 Polaroid.

Centre Street, New York, 2016

‘Mario lent me his Hasselblad and said,

‘You have to take good care of this,

it’s the Rolls-Royce of cameras.’’

Vanina Sorrenti in conversation

Neville Wakefield: I was joking with Mario that this is a sort of family group therapy session, where we can all discuss your relationships to each other through the lens of photography. So, you grew up in a family where photography was all around you, cameras were all around you.

Vanina Sorrenti: My mother was a fashion stylist and at the time, in the 1980s, children’s fashion was really booming. We were always in the mix modelling for her in shoots and in fashion shows with lots of other kids. It was an extended community, it was lots of fun! That’s how we were first introduced to the industry and to photography.

So, your first experience was in front of the camera?

Yes, I was eight years old. Because my mother was working all the time, we would go with her when she was prepping shoots. Mario, Davide and I did a few shoots with her and really enjoyed it, and as more requests were coming in she signed us with Ford [Models] kids agency. We would go to a phone booth and call our agents after school to see if we had any ‘go-sees’ to go to – that was a way for my mother to keep tabs on us and out of trouble.

Do you remember anything specifically from that era?

Yes, we modelled for this brand called Gitano, one of my mother’s clients. She really made it into a cool brand. She always cast the same gang of kids and we all had lots of fun together. You got to skip school and do pictures all day. There was always candy, chips and soda on set, loud music playing. We danced to Cyndi Lauper, Cocteau Twins, Run-D.M.C… Mario would breakdance and we would always try to get up on our toes to mimic Michael Jackson’s Thriller. It was the 1980s, it was big teased hairdos, hairspray and gel. Leather jackets, layers of fluorescent mesh T-shirts, three-studded belts and baggy jeans, with puffy socks and high tops, and a thousand rubber bracelets with fishnet gloves! My mother and Steve started a creative agency called Sorrenti & Sutton where she was styling and Steve was shooting. They worked as a team on all their projects. If we asked for weekend money, my mother would say, ‘Come to the studio and work.’ I was about 12 years old and we did odd jobs like filing models’ headshots in alphabetical order. We would help with whatever had to be done around the studio.

Was photography something you grew into, rather than there being a moment where you realised you wanted to be the one making the image rather than participating in it?

It was gradual. After high school I started to assist my mother’s friends who were stylists and got the chance to see other photographers working. We were on set with Mark Borthwick, Ellen Von Unwerth, Annie Leibowitz, Sheila Metzner, Bruce Weber, Sante [d’Orazio]… They were all incredible learning experiences. After a few years of assisting, I started working on my own as a stylist for Vogue and Marie-Claire, on photo shoots with my mother. And then, when Davide started shooting, we worked together on some really great editorials for i-D and Surface magazine. Taking pictures myself was something that evolved over time and quite naturally. In my early twenties I was always taking pictures with a 35mm camera that Steve had given me. I was shooting a lot of black-and-white film, and I had a camera on me all the time. I kept binders of contact sheets. I really loved the idea of them as cinematic sequences. Little films documenting stories of my life, my friends, everyday street life.

Was it the style that drew you in first, or the image?

I think it’s many elements that come together – the subject, style and light. I was mostly drawn to what was happening in the moment and capturing it with friends, family and people I connected with on the street. It was definitely more cinematic and reportage at first. I was free from any definitions and just exploring the world around me. Eventually I found a language and style as I gained more knowledge and control of the medium, exploring different films and camera formats and delved into the history of photography. I spent hours at the bookshop A Photographers Place in SoHo, where there were so many books stacked everywhere from floor to ceiling; every nook and cranny of the place was filled with rare, vintage photography books. From early turn-of-the-century to contemporary: Stieglitz, Bill Brandt, Edward Weston, Man Ray, Julia Margaret Cameron, Berenice Abbott, Diane Arbus, Will McBride, Duane Michals and Lee Friedlander were some of my favourites.

‘We’d go to a phone booth and call our agents after school to see if we had any ‘go-sees’ to go to – that was a way for my mother to keep tabs on us.’

When did you come to see yourself as a photographer?

A defining moment was not long after Davide passed away. Surface magazine had asked my mother if I took pictures and if I wanted to be part of their ‘Avant Guardian’ issue, which featured young unpublished photographers from all across America. They would have exhibitions travelling through San Francisco, New York, LA… And I said, ‘Yeah, why not?’ So I went through all my binders and started editing and then went into the darkroom and printed a bunch of stuff and sent it in to Riley [Johndonnell, Surface magazine co-founder] who loved it. He asked if I wanted to publish the images for the issue, or if I’d like to shoot something in particular for it. It never occurred to me to shoot a fashion story. Up until then, I took personal pictures as an amateur and was more into cinema. I loved foreign films: I would go to Kim’s Video and watch a lot of indecent foreign films. I was shooting a lot of Super 8 and 16mm. It was all very personal. But when the ‘Avant Guardian’ project happened, it all shifted. Mario lent me his Hasselblad and said, ‘You have to take really good care of this, it’s the Rolls-Royce of cameras.’

Had you used one before?

No, but I knew the basics. He showed me how to load the film and use the different lenses. I went to a few showrooms to pull the fashion – all the young designers like Susan Cianciolo, Bernadette Corporation, Rebecca Danenberg. Then I asked my girlfriends if I could take their portraits: Susan Cianciolo, Jade [Berreau] and many others, and I went over to their apartment. We shot a series of different looks and set-ups.

I remember those pictures.

I couldn’t stop shooting. I loved the format. I’d never shot with the square format of the Hasselblad before and it was a whole new experience of framing and composing an image. I think shooting with the Hasselblad played a big part in defining my style and my language. I showed my mother some of the contact sheets and she suggested I start editing as I had so much material. All the images were beautiful moments in their own right but you had to figure out which one fit in the context of the linear story, not just as a body of work.

That’s funny, because I was going to ask you how you characterised your approach in relation to that of your brothers or that of your mother.

Sometimes we can have very similar ways of going about it but we digest them very differently. We can be inspired by the same references but we have our own unique way of expressing it. For example, I was influenced and inspired by Balthus at the time; I took those images for Surface, which people describe as classical, feminine, Romantic images. But he’s a male painter, and the images had this innocence but also a very strong dark taboo undertone. I think that there is so much romanticism in my brother’s and mother’s work, we just have different ideas of what is romantic. I’m drawn to the grey zone where things aren’t so black and white.

What were the films that were influencing you?

I loved Tarkovsky at the time. I was really into his movies, like Mirror and Nostalghia. Also Miloš Forman’s early films, Loves of a Blonde, The Firemen’s Ball… All of Cassavetes. I was also very influenced by religious Italian Renaissance painters like Botticelli and Da Vinci. I loved the expressions on the subjects faces and their hand gestures.

Something that is really fascinating, looking at your creative evolution as a family, is that it’s also a document of New York, a city that runs through your mother’s work, with the 1970s and 1980s downtown scene, and then your and Mario’s and Davide’s vision of it, and then obviously Gray’s coming of age in the 2010s and 2020s.

I think that growing up in New York definitely gives you a sensibility that is unique. There’s an intensity to the city that vibrates through everything. An amalgamation of cultures. Now that I’m living in Milano, when I go back to New York I see a madness on the streets that I was so used to when I was living there but that I’m no longer confronted with in my everyday life. You were just surrounded by wild energy and constant contradictions. It’s fascinating and disturbing at the same time. I find it inspires me and infuses me with ideas. When I’m shooting it’s like a ritual where I try to find silence and create a stillness between me and the subject in a seance, very much like a painting. The camera is like an umbilical cord that connects you and records it.

‘I think that there is so much romanticism in my brother’s and mother’s work, we just have different ideas of what is romantic.’

Can you tell me about Davide’s work?

Davide’s work was very embedded in New York. He photographed and documented everything around him, his friends, family. He pretty much had a camera on him all the time, and was someone that had very strong connections with people, even just walking down the street or in a deli. Everyone knew him in our neighbourhood, people loved him. He had a fantastic sense of humour and such a beautiful way of connecting with people from all walks of life. There’s a strong connection and intimacy in the interaction with his subjects and environment. I think it really comes across in his pictures. Davide has an extensive body of work, considering the timeframe from when he started taking pictures. My mother has curated several books and exhibitions on Davide’s work and has kept his spirit and lineage very much alive. People have been inspired by Davide’s sensibility and legacy since the late 1990s and still today I see so many young people paying tribute to him and his work. For me, Davide is my little brother, and we were very close. His spirit is constant within me.

When you think of Davide today, what is the first image, memory or feeling that comes to mind – and how does it connect to the way you see creativity and legacy within your family?

His laugh and smile is always the first thing that comes to mind when I think of Davide. I am inevitably influenced by my whole family, not only in my work, but in life. We are extremely supportive of each other. Fortunately, we have been able to work in a creative field and industry and all our children continue that lineage. It’s so inspiring when I look at the work that they’re doing, I’m blown away! I step outside and I look around, I feel very fortunate to have such a strong bond with my family and the unconditional love we share.

That brings this perfectly to my last question: what would your advice be to an emerging photographer?

Make it your own. It’s about adapting and finding new ways of being creative and expressing your vision, regardless of the context. When I was younger I had to adjust from working one-on-one with my subjects to orchestrating a team of creatives. With a team, the goal is to fuse your aesthetics and ideas into one vision. Communication is everything.

Gray self-portrait.

669 Polaroid.

Connecticut, Sunday April 19th, 2020.

M Le magazine du Monde.

‘Someone once told me that they could feel

my photos on their skin, and I loved that.’

Gray Sorrenti in conversation

Neville Wakefield: So, you grew up surrounded by photography. Was there an inevitability that you were going to follow the family tradition? Or was there any moment when you felt that you needed to rebel against that? And if so, how?

Gray Sorrenti: I think if there’s a moment of rebellion, it might be now – but I’m good. I’ve been surrounded by art in general my whole life; I was brought up on it by my parents. They would lay out pens and paper and cover our walls, floor to ceiling, with massive pieces of paper, and let me and my brother go crazy – painting and drawing all over the place. So, it started there. I had this idea that I was going to be a painter because I would sit alone in my rooms for hours painting, drawing and collaging. The alone time is where my mind would explode. I was applying for art school while in high school and kind of randomly fell into taking pictures because I was shooting kids my age being bad in New York.

You were just documenting your social surroundings?

Yeah, it was just my surroundings. I remember this one photo that really stuck with me – it was early on, I had just started taking pictures of my friends. We were all crammed into a room, hiding out, passing around a harmonica they’d turned into a pipe, smoke flowing out of it. It was chaotic and kind of ridiculous, but also completely normal – that was New York youth culture at the time. We were raw, messy and inventive.

And only photography could have caught that moment, right?

It was as if the camera became my own eye. I never approached it with seriousness; I was simply tracing the rhythm of my life as it unfolded. The act of documenting felt instinctive, almost effortless. Sometimes it was as simple as laughing, and that laugh felt like the click of a button.

‘As a kid, I was super wild and all over the place, but when I started taking pictures for fashion it gave me a purpose and a reason to focus.’

You mentioned just before that your initial ambition was to become a painter. Were you aware of your grandfather’s paintings?

When you’re inside your family, you don’t really think about it – it just feels like one unit. I never looked at my grandfather and thought, ‘Oh, he’s an oil painter.’ It was more like: this is my art, my family is my art. We protect each other and live inside this bubble – a beautiful bubble to create in. It’s not about shutting out the world, but about holding on to something unique that we share.

That’s a nice way of putting it.

Yes. Just going back to my early experiences of shooting my surroundings: maybe this is a little much for the interview, but once in the Catskills a few friends and I were tripping on mushrooms. I had my camera with me, and for some reason I couldn’t take it away from my eye – I wanted to see everything through it. It was like the camera had become my eyeball.

So the camera becomes prosthetic. An extension of the self.

There’s always that barrier between you and whoever’s in front of it. An extension of yourself, yeah, but at the same time it’s one of the most invasive objects. I always think a camera is the one thing between you and your subject. That is kind of the problem with it. If I could just jump over the camera. It can be about intimacy and connection, but it can also carry this weight of disruption, even death…

[Susan] Sontag writes about, literally, ‘shooting.’

Exactly. I think about that a lot. Honestly, if I could take pictures without a camera, I would. And that’s exactly what I’m trying to explore in the book I’m making.

Tell me more.

Since 2016, I’ve been taking screenshots during FaceTimes – family, people I’ve loved, breakups, friendships, moments of laughter, people crying, even someone in the bathtub. It’s just fragments of my life. What I love is that there’s no camera in the way, no object separating you and the other person. It feels like capturing something with your own eye – direct, unfiltered, honest.

How would you say your approach to photography relates to the approach of your dad or your grandmother or your aunt?

You know, my dad is extremely technical. I always call him ‘The Shapeshifter’ because he can do anything. Absolutely anything and everything. I take pictures based on feeling – I think my dad does too, and my aunt as well, but that’s their story to tell. Someone once told me they could feel my photos on their skin, and I loved that. I’ve thought about it ever since, because that’s what I want – to feel the subject, the landscape, whatever it is, in its purest form, as close as I can get to it.

Its purest form being its most unmediated form.

It’s most unmediated, most vulnerable. Something that you can relate to, but also something that makes you feel uncomfortable because you relate to it so much.

‘My dad is extremely technical. I always call him ‘The Shapeshifter’ because he can do anything. Absolutely anything and everything.’

You all grew up in New York City. Three generations effectively grew up in New York City and it’s been the backdrop, but it doesn’t necessarily appear in your work. Would it be true to say that you’re more interested in social architecture rather than the architecture of place?

I like taking pictures of whatever I like. That’s the truth of it. Whenever someone tries to put me in a line, I always go off it. And then when I try, I can’t figure out how to stay on the line.

That intimacy and vulnerability you’ve talked about, is that ever at odds with the fashion image, it being loaded with meaning, with style? Are you trying to do something other than that?

Yeah, 100 percent. I really want to make films. I’ve been working on my first feature-length documentary for nine years now, and I’m finally in the last part of it – the editing. Documentaries just take time.

What’s it about?

Dirt bike riders and bike life culture in New York, both men and women.

Was that a case of immersing yourself in that particular community and culture, and then, as you’ve always done, shooting your surroundings?

Yeah. I met them when I was 17, still in school, and they quickly became some of my closest friends – really, my family. I started riding with them, and I realised they needed someone to help tell their story. So I offered my hands and whatever knowledge I had, and we’ve been doing it together ever since.

The film feels quite distinct from your work in fashion. Do you consider yourself anti-fashion?

No, I’m not anti-fashion. I love it – I grew up in it. But I grew up in a different time, and what I saw and learned as a kid feels very different from what it is now. Still, I think each to their own. Fashion is a beautiful thing, and it’s given me so much. As a kid I was wild, all over the place, but shooting fashion gave me purpose – it gave me focus. I think the art of fashion is beautiful. There are some incredible designers out there, and also incredible young designers who, if given the chance, could really change the industry.

Other than the incredible bond that you all have and the incredible common interest in photography, is there anything you would identify as being unmistakably Sorrenti that connects your family’s photographic work?

Yeah, so much. We’re all so alike. It’s almost disgusting how alike we are.

Does that create problems?

No, it just causes more happiness and more laughter. Maybe the one thing that connects our art most is how sensitive we all are. In every aspect of life, not just within art, but the way that our hearts work, our emotions, the way that we view, understand and perceive the world.

Would you say that’s through the common lens of emotion?

For sure. And our hair. We all have silky smooth brown hair.

That’s amazing.

Yeah, my dad said something to me once that really stuck. We were driving down the West Side Highway – I think he was dropping me at school, and I had just started taking pictures. He was always giving me little pieces of advice, and who knows how much I was really listening back then, you know? He pointed out the window and asked, ‘What do you see?’ Me being a teenager, I just shrugged, kept my finger pointed at this little spot on the water, and said, ‘I don’t know… not sure.’ And he said, ‘Exactly. You see that? Not everybody sees that. Only you see that. Only I see that.’ That moment has stayed with me ever since.

And to my last question – what would your advice be to someone who wanted to become a photographer today, aside from blowing the dust off the current fashion system?

Something that I abide by always, and I even struggle with it – because obviously fashion is a super difficult world to work in – is to really just have fun with what you’re doing. Love it. Because if you don’t love it and you’re not having fun, then it’s not worth it. And I have to remind myself of that all the time when I have some difficult client that’s telling me it’s not good enough. It’s yours, let it be you.

Fantastic, that’s great advice.