& Graces Mews

The story behind London’s new photography gallery.

Interview by Jonathan Wingfield

The story behind London’s new photography gallery.

Tyrone Lebon isn’t the first fashion photographer to have channelled his accolades and earnings into founding a photography-focused exhibition space, but that doesn’t make his Graces Mews gallery any less unique. Back in 1905, pioneering fashion photographer Edward Steichen co-founded The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, along with Alfred Stieglitz, arguably the most important photographer of his time and an advocate for photography as a legitimate art form. Based in what had been Steichen’s New York portrait studio, the bijou gallery showed works from the Photo-Secession – an early 20th-century movement that promoted photography as a fine art. Although brief, The Little Galleries’ 18-month existence is widely acknowledged to have changed the course of photography.

Fast-forward 120 years to Camberwell, in South London. Recently-opened Graces Mews is situated in a 7,500 square-foot converted printer’s workshop. The gallery boasts three exhibition spaces, a working photography studio, a private print-sales room, a custom darkroom, state-of-the-art scanning and digitalisation equipment, archival cold storage and a photography bookshop. It is the brainchild of Tyrone Lebon, one of contemporary fashion’s most sought-after photographers, who also personally bankrolled the project. Ambitious, verging on the quixotic, it is born out of Lebon’s seemingly boundless love for all things photography-related: books, zines, prints, analogue cameras, dead-stock film, ‘all sorts of geeky kit’, and, most importantly, the wider community of photographers. In particular, Lebon is drawn to those artists, contemporary or historical, who operate in less conventional realms, in the margins, often overlooked or underappreciated.

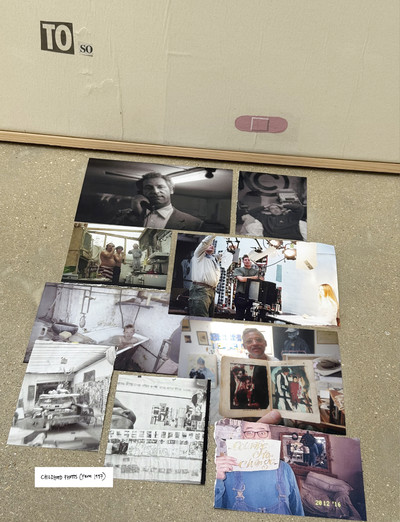

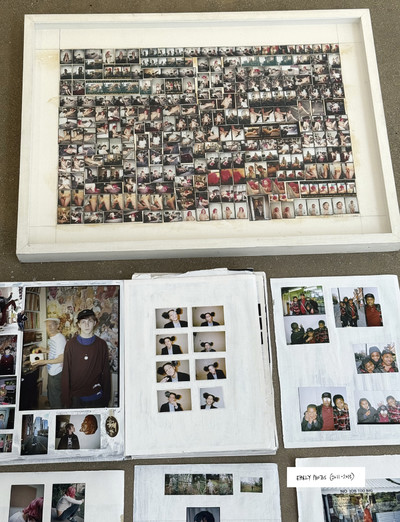

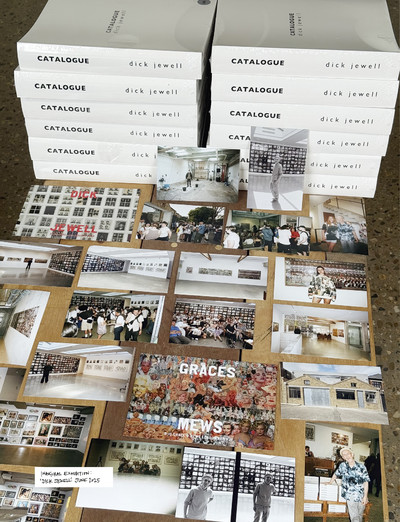

Graces Mews’ inaugural show, during the summer, presented a career-wide survey of lesser-known British artist Dick Jewell, whose collage and film works are steeped in photography as social anthropology. Jewell has, since the early 1980s, been a friend and close collaborator of Tyrone’s father, the one-time fashion photographer Mark Lebon, who today is perhaps the embodiment of the cult artist. Having observed from close quarters the sprawling, chaotic scene at his father’s Crunch Studio – a former-garage-cum-creative playground in North-West London – it’s easy to understand the affection that Tyrone now holds for iconoclasts, self-saboteurs and all things countercultural. ‘Whether it’s Dick, Dad, or whoever else,’ he explains, ‘I have a love for people who are either uninterested in or incapable of fully capitalising on their work, because they’re too busy being an artist.’

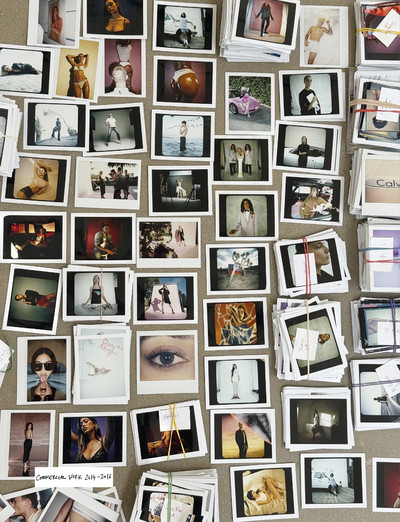

Pumping his earnings from commercial work into Graces Mews isn’t an isolated example of Lebon’s singular characteristics as a fashion photographer: his largely analogue approach scares off many potential clients; he founded his own artist representation agency in 2018 (DoBeDo Represents, whose roster currently includes Rosie Marks, Johnny Dufort, Jim Goldberg, Frank Lebon, Nigel Shafran and Takashi Homma – although Tyrone himself has now stepped back operationally); and he’s chosen not to produce a single editorial story in over a decade, preferring instead to divide his time between shooting largely-unseen personal work and some of contemporary fashion’s most arresting and ubiquitous campaign imagery: Céline (circa. Phoebe Philo), Calvin Klein, Bottega Veneta, and most recently Alaïa.

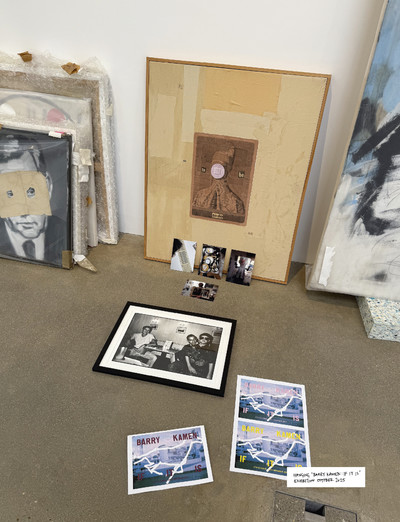

System sat down for a lengthy chat with Tyrone as he was installing Graces Mews’ second exhibition: the work of the late Barry Kamen. He’s using the extensive show to reclaim Kamen’s rightful legacy – that of a prolific artist and painter, more than fashion’s sometimes reductive memory of him as a prominent figure in 1980s London style.

BARRY KAMEN: IF IT IS

EXHIBITION, OCTOBER, 2025.

Barry came into my life as an uncle figure, I suppose. As a kid I remember his spirit was generous and warm and he always had time for me – traits that a child remembers about rare adults who shine with some extra energy most adults don’t have. Growing up, I became aware that he was a painter, and I went to one of his shows when I was about nine years old.

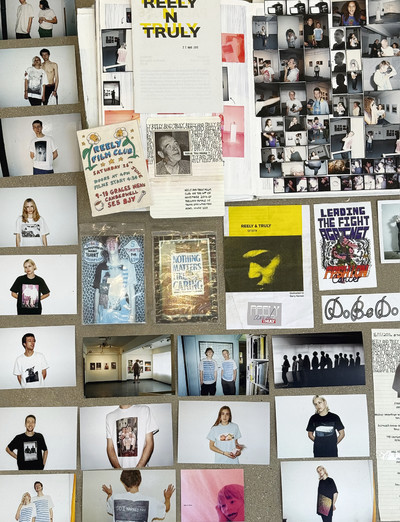

Dad collaborated closely with Barry’s older brother Nick for years, doing photos and music videos throughout his pop-star music career in the late 1980s and early 1990s. It was at this time that I first saw Barry’s painterly animations that he’d made as overlays for sections of those videos. Years later, when I ended up making films myself, I started using that same technique. I made a documentary in 2014 called Reely and Truly about 20 photographers. There was a short animated sequence about Jason Evans and Barry kindly agreed to work on it for me. My brother Frank was assisting him, and I was so excited and honoured that he had collaborated on it.

By then I was about 30, and I’d seen Barry infrequently over my adult years. But from that point on I started to visit him in his studio in East London. Now and again we’d have lunch, and one time while I was there he asked if he could do a painting of me at some point. I loved his studio. He was always working on something new each time I saw him: an animation, a painting, charcoal drawings, a collage using newspaper lettering or letterpress. I really cherished that short period we were in touch more closely. In October 2015, Barry suddenly died. We heard the news that he’d had an issue with his heart and literally dropped to the floor while painting in his studio. It was totally out of the blue.

Tatiana, Barry’s wife, oversees Barry’s estate with a small team. I hadn’t been in touch with her for a long time, but once we reconnected last year we soon started planning how we could work together to do something at Graces Mews. At first we were looking into a way to show his animation work only, but soon the idea developed into a bigger show, with the animations placed centrally, surrounded by a selection of his larger paintings and smaller works on paper. A lot of the work hasn’t been seen before.

Both Barry and Nick passed away in their 50s – very young. And when Barry’s show opens in October, it will be the 10-year anniversary of his death. While we were hanging the show a few days ago, surrounded by all of his work, it surprised me quite how present he felt. Feeling him more closely, in the presence of his work, actually reminded me, for the first time in a long time, quite how much I missed him. Barry is often remembered by people for the Buffalo scene, but to anyone who knew him closely he was first and foremost a painter and an artist.

CHILDHOOD AND FAMILY HISTORY

Mum and Dad split up when I was about two, and Dad soon moved into a garage up in Kensal Green. It was his home but also more prominently his studio. I grew up visiting him on weekends, with longer stays through the school holidays. My main memory of that time is that the place was always busy; filled with lots of stuff and busy with his photoshoots. There was a period when Crunch, his production company, was run from there too, and even when that closed there were always a lot of people dropping by. The winters would be cold and leaks would drip through the corrugated plastic roof, but in the summer the big doors would open out onto the street, records would be playing, and we’d have showers with a hose pipe.

Looking back I would say that although at the time I was probably more interested in watching TV and playing football out on the street with my friends, but it must have had an effect on me. There was a constant creative, collaborative energy and dialogue. Yeah, he’s not really interested in doing things in isolation. He only likes to work on things when he can work collaboratively, with someone else, or a team.

In contrast to Crunch, my mum’s house in Whitechapel was minimal and clean. This was my main home where I stayed most of the time. When I remember back to that time, I think of the house as being peaceful and quiet, and aesthetically it felt like every item in the house was significant and had been selected. My mum worked with my stepdad, who was a furniture and product designer. In a lot of ways, the two households couldn’t have been more different, but I found it exciting to jump back and forth between the different worlds.

I think my mum, pretty understandably, found my dad quite frustrating through those years when he was particularly chaotic, and as a result I think she was pretty open about her disapproval for his job and some of the people that he worked with. This might have been one of the origins of my suspicion of the fashion industry. Although, to be honest, any person with their head screwed on right would probably find various aspects of it pretty dubious.

By the time I got to university to study social anthropology, I would say that I was questioning a lot of things about the world – and I remember questioning my dad about what I saw to be the many negative effects the fashion industry had on society: encouraging people to desire things that they don’t really need, twisting beauty ideals, encouraging consumption and capitalism… I was idealistic and also probably a bit naive. At the time, Dad’s girlfriend was an agent for fashion photographers – Julie Brown, who owned MAP – and I remember quizzing her, ‘How can you sleep at night being involved in such a toxic industry?’ Fast-forward less than 10 years, and she was representing me at MAP [Laughs].

FIRST STEPS INTO PHOTOGRAPHY

I went to boarding school when I was 12, and living there with about 600 other kids was pretty overwhelming. Discovering there was an old hidden darkroom I was allowed to use, and being taught how to process film and print in black-and-white chemicals, was like finding my own private hideaway. Photography helped me get closer to people that I was interested in, and was a shortcut to a type of intimacy that in normal life would take time to be earned. That was a huge thrill to me, and is a part of photography that still draws me to pick up a camera to this day.

Finishing school and going to university, I’d been taking a lot of photos of my friends, just documenting my life. I knew that photography was always going to be part of my life, but at that point I was thinking that I was going to try to be a documentary filmmaker. I’m not sure we have time for me to go into the full story of the next 10 years, but I’ll give a quick summary: I finished my MA, and struggled for a few years trying to make documentary films. Got into a lot of debt. And after a string of jobs, I ended up freelance photo-assisting and could just about pay my rent and survive off that. Kind of… [Laughs].

How did I end up getting drawn into fashion after being so convinced it was a sinister world? I wouldn’t like to sound like real life beat the idealism out of me, as I think it’s more complex than that. But I think I’ve always held that initial mistrust of fashion in the back of my mind, even as the industry fully embraced me. I was doing a few small portrait shoots of musicians for magazines like i-D, and then gradually started shooting fashion editorials. Probably the most significant thing from that time was the friendship and collaboration I formed with [stylist] Max Pearmain. We met in the i-D office I think. He was interning. The pictures we took over the next few years started to open my eyes to the pleasure and the satisfaction I could get from working within the constraints of a magazine shoot. Max had studied fine art at Slade and the way we both approached editorial felt very sideways. The clothes came last. We were just trying to make interesting pictures and play with all the access and material that fashion provided. At the time, the work we were making felt really exciting to us, and different from most of the super-digital and hyper-retouched imagery that was dominating magazines and fashion advertising at the time. I don’t think either of us ever really thought that we’d get work from those shoots; to me, I certainly felt more like an outsider that was having fun, kind of taking the piss and holding a mirror up to the more ridiculous and grotesque sides of fashion.

Anyway, at this point I had been with my agent for a few years and had barely got a single commercial job. Meanwhile, I started to feel like I’d said all I had to say in the world of editorials. This was 2014. Seemingly, no-one was interested in hiring me, the photos I was taking were costing me money to take, and I was thinking, ‘This has all been fun and everything, but where’s it going? Maybe it’s time to think about something else.’ Then I got an excited call from my agent saying that Phoebe Philo wanted to discuss shooting the campaign for Céline – and that was basically when everything very suddenly flipped.

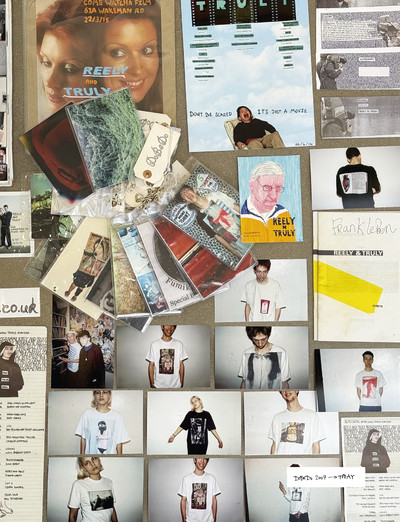

DOBEDO,

2007 TO PRESENT DAY

DoBeDo began in 2007 as a ‘platform’ – for want of a better word. It was in fact a lot of different things: we ran a regular film night and club night, put on a few photography exhibitions, published books and made products. At that time it was all based around a website. This was before Instagram, and we had ‘blogs’ where all sorts of photographers kept daily photo diaries that you’d have to visit the website to look at. Back then it was far harder for people to put their own stuff online themselves, so we’d sell all sorts of things: photographers’ books, zines and prints, music MP3s, T-shirts by designers like Judy Blame (he liked to call us ‘DoBeDon’t’) and London brand Trapstar. DoBeDo was a mix of different things, done entirely for the love, and to build and support an existing community – mostly of photographers.

In the back of my mind, even back then, I had a bigger dream for DoBeDo that involved some kind of real-world home. A permanent place to put on shows, host events, have a shop… I wasn’t sure exactly, but for the idea to be properly realised to its full potential it couldn’t simply be online.

COMMERCIAL WORK

(MAKING MONEY TO MAKE A GALLERY)

It’s quite hard for me to make sense of what happened next. But the best way I can describe it is that because some part of me was never truly convinced that I was destined to be there, I always kept fashion at arm’s length. Somehow by trying to resist it, I unwittingly created a dynamic of being really selective and saying no to a lot of things. The more selective I was, the better the opportunities were that came back. After Céline, there were a couple of big Calvin Klein campaigns, a music video for Frank Ocean, a run doing YSL perfume ads. Other highlights have been Bottega Veneta, Burberry, Miu Miu and now Alaïa. It doesn’t actually sound like so much for 10 years of work, but it certainly felt like plenty.

When this all first took off, I had a lot of fun travelling and just being super excited by all these new opportunities and challenges. Then, at some point, I had a bit of burnout. I ended up moving away from London, following a girlfriend to LA to take some time off. Eventually I started to get some energy back, and with no distractions the idea of a gallery space kept coming into my mind. At first, I started looking in LA but soon realised it was never going to be my home, and after two years there, packed up and came home. This was when I began shooting for Bottega, and Dan Lee [creative director from 2018-2021] was super loyal to me – we did every campaign for those three years. As a result, I started to save money, and so for the first time the dream of having a photography gallery became a possibility. At some point in 2019 I started properly searching for a location.

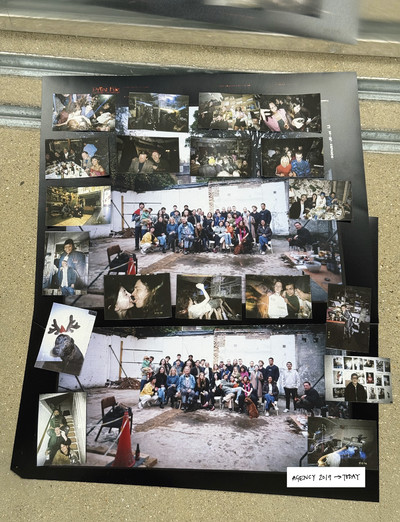

AGENCY

A bit earlier than this, there were some changes happening at MAP. The owner had sold the company to a large conglomerate called Great Bowery which was owned by a hedge fund. Pretty quickly, I could sense a shift in the energy and growing pressures that were being put on staff and artists. To cut a long story short, I wasn’t enjoying this new dynamic and so started to look into what it would take to set up an artist-led photography agency. We launched DoBeDo Represents in 2018, and I was excited by the challenge of setting up a business. The early days were pretty rocky. I hired some questionable people and Covid was a very close call, paying for staff and offices in NYC and London. But the big turning point was the arrival of Nikki [Stromberg, managing director]. Since she started, and took leadership of the company, the whole thing has been smooth sailing. Her taste level and dedication to the agency being artist-led has meant that I can focus on my photography and other things like the gallery.

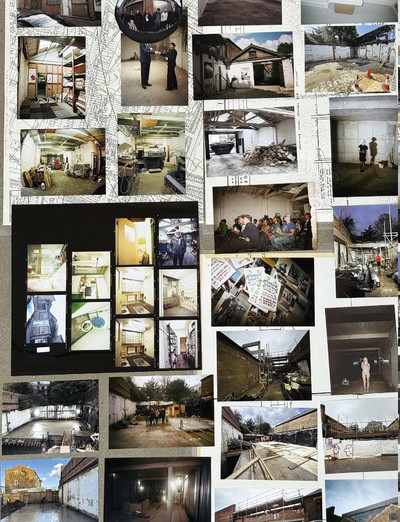

9-10 GRACES MEWS

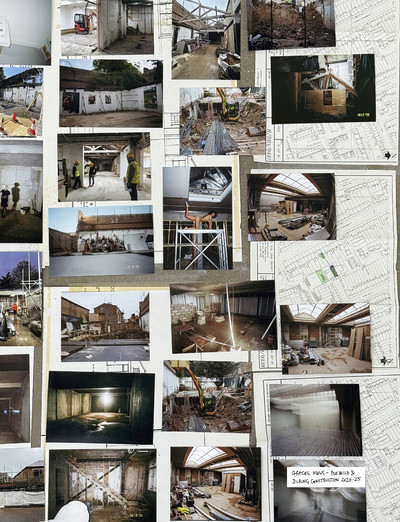

I looked for over a year and was lucky to eventually come across an amazing place that wasn’t publicly marketed. It was a pair of single-storey printer’s workshops down a mews in Camberwell. Two A-frame buildings side-by-side, each with a large back studio space. I immediately fell for the place, and it didn’t take much imagination to see the potential – or the amazing daylight the building naturally had. The owner was in his 70s and looking to retire after owning it himself for over 30 years. He didn’t want to sell it to a developer who might turn it into flats, and was happy to hear I was looking to turn it into a gallery. I got the keys in January 2020. And then Covid struck. The first architect had a plan to have the place fully ready for us to move into within a year; a very simple refurbishment that wouldn’t have required extra planning. But once the process began and we really started thinking about how the space would be used, we realised that we needed more space. After a long and sometimes painful journey (multiple architects, an additional two years digging out a basement) we eventually moved into it in May this year – five years later.

Graces Mews has three exhibition spaces, a print-sales room where you can look at and buy work from over 50 photographers, private colour and B&W darkrooms, and archival cold storage. The program is photography focused and we are planning to have three or four shows and six new publications this first year. The photography bookshop at the front of the gallery is open to the public five days a week, all year around. We have a film club a few times a year, photography workshops every couple of months, and a bunch of film screenings and book launches scattered throughout the year.

To hear the buzzer ring, and for people to come in and look around the shows downstairs, is such a good feeling. Some days, we had over 100 visitors for Dick’s show. It is a bizarre feeling for this thing I’ve been imagining for so long to now be alive and working for real.

INAUGURAL EXHIBITION:

DICK JEWELL, JUNE 2025.

Dick was the obvious choice for a first show because of the depth and the breadth of his work. I’ve been a fan of his since I was a teenager. Dick’s work for me is a type of visual anthropology. He’s studying culture through image collection and analysis. The way his mind works, he takes groups of imagery and distils a truth about people or society or culture. It’s so particular to Dick and it’s so spot on. I’m describing it in a way that maybe sounds dry, but it’s not at all; it all has a sense of humour too which I love. His work is also tied up with whatever the current technology is: I love his work from the 1970s when it was made with scissors and glue, collecting magazines and printed materials. In the 1980s he moved into TV, taking photos of the screen. Then, once the internet hit, Dick’s mind must have been blown by the quantity of material online. His 4000 Threads book and video installation is, for me, an amazing, playful portrait of humanity through found online imagery.

With the quality and quantity of work he has produced over the years it surprises me that he has had such little attention throughout his life. Maybe he wouldn’t consider it that way, as he’s certainly had work in a variety of major arts institutions; recently, for example, he had a few works in the Tate Modern’s Leigh Bowery show, but for me he is deserving of a lot more recognition. I think part of it, and what I actually admire about Dick, is that he lives purely to make his work. He has never been especially motivated by any of the rest of the stuff that goes with being a capital-A ‘Artist’. He certainly hasn’t been influenced by financial motives. For years, I was trying to buy some work from him, and he was always very elusive so I eventually gave up. Presenting a full retrospective of his lifetime of work, as well as publishing a catalogue raisonné to accompany it, has been really satisfying. And at last I can buy something of his [Laughs].

FINAL THOUGHTS

In the five years between getting the keys for an empty building to it becoming a functional gallery and studio space, there’s been so much to be excited about. But it’s also been a painful struggle at times. There were months when the construction bills were ter-rifying. And the never-ending stream of challenges and setbacks was exhausting. I wondered if I’d bitten off more than I could chew, but I always kept my eyes set on the future – on when the place would be finished and how excited I was for that.

Walking into the finished space for the first time when the builders had left, was a strange moment. I’d always imagined I’d be immediately elated, but when it happened for real I was just exhausted. But, you know, having had the chance to settle in a little bit now, and watch the first shows come together, and see the shop space set up, it’s beginning to feel really joyous. Like it was all worth it – although I’ve definitely got more grey hairs now than I did five years ago. These days, I’ll get in early in the morning, before anyone else has arrived, have a cup of tea while the morning sunshine is coming through the windows, and think to myself, ‘Wow, this is going to be a really special place.’