How Aldo Fallai defined the Armani man.

By Giusi Ferrè

How Aldo Fallai defined the Armani man.

Before having my own label, I used to collaborate with different brands. Some of them were based near Florence where Aldo Fallai had his graphic design and photography studio. The decision to get in touch with him – as well as with other guys from Tuscany – was spontaneous but also quite natural. Everything was new to us, and none of the things we had seen before seemed to be able to express the way we were feeling. We tried to develop our ideas by working side by side, having long conversations, meetings and rehearsals. It wasn’t easy either.

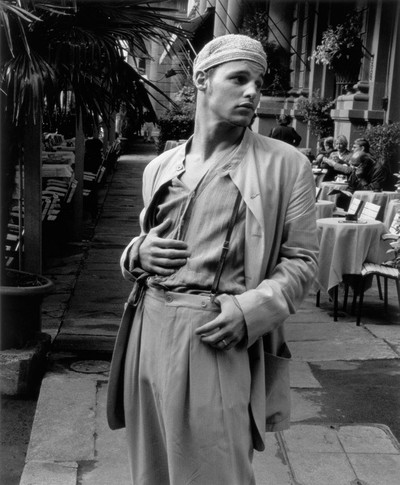

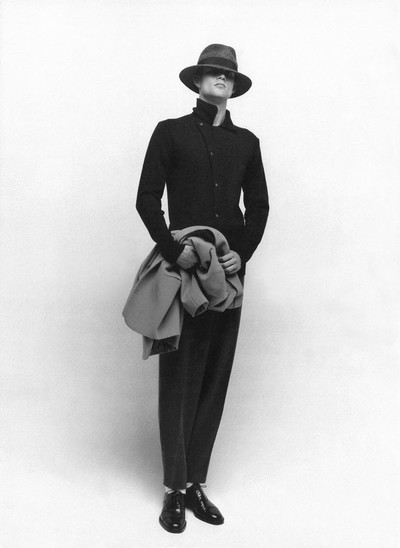

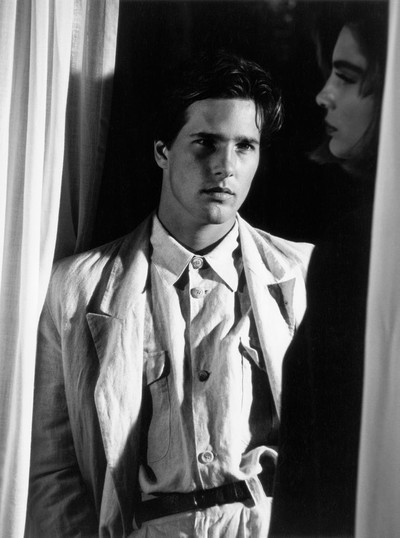

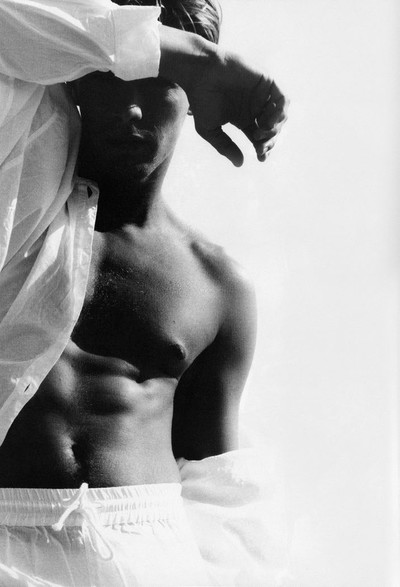

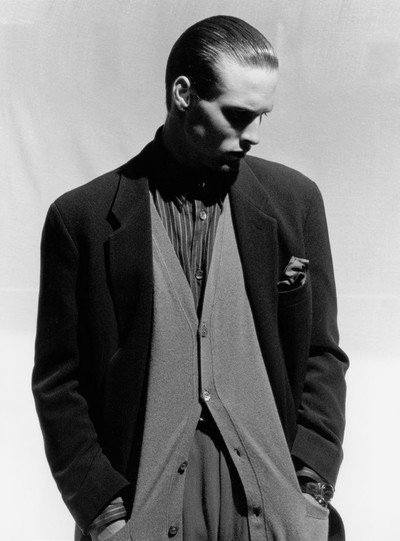

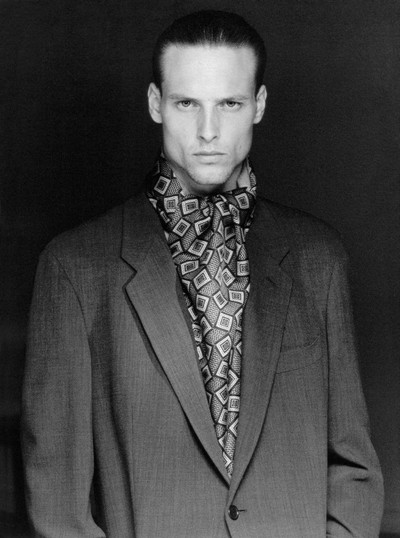

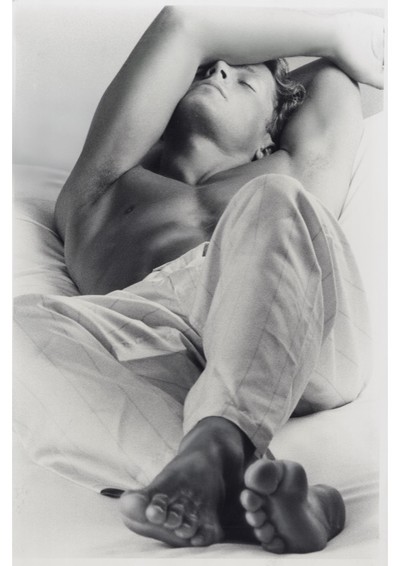

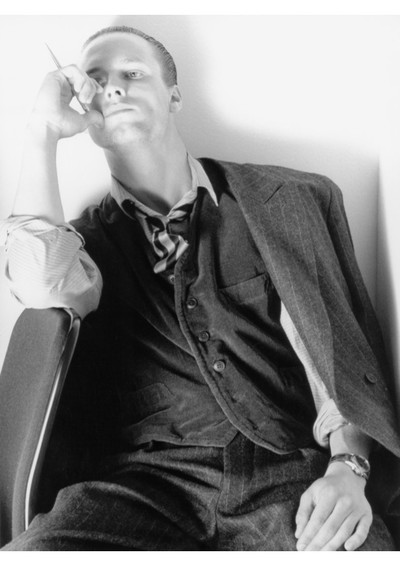

The menswear imagery was a deep reflection on life, experiences and personal memories which could tell the story of everything I believed. The models had to be natural, neat, expressive. I wanted faces that could suggest the ability to think and that demonstrated fullness of character.

For many years, garments had been made with stiff fabrics that rigidly boxed up the body. I preferred naturalness, nonchalance, small flaws,

and that’s why I chose soft fabrics and materials which were able to caress the body as it was never done before during the Industrial Revolution. It was a new sensibility that went beyond the stereotype of muscle men because it revealed a sense of rigour and precision that didn’t affect men’s sensuality. Together with Aldo Fallai, we were able to realise this ideal in our campaigns.

Giorgio Armani, April 2014

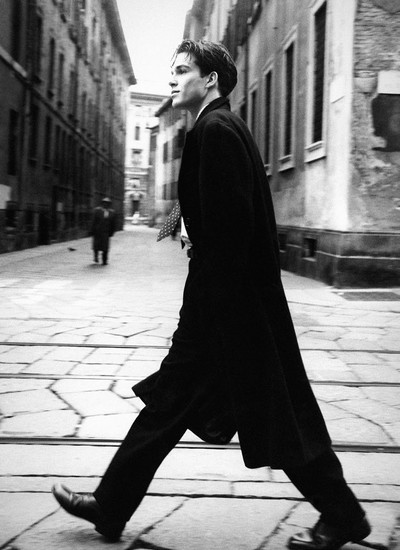

In Milan in the early-1970s, a young graphic designer called Aldo Fallai met an equally young fashion designer called Giorgio Armani. They both shared dreams of creating a new and fiercely precise menswear aesthetic, one that would combine stylistic perfection with sculptural poses and brooding sensuality. It took Fallai to pick up a camera in order to adopt the role of Armani’s visual interpreter; and in doing so he was able to transform their utopian Armani man into a visual reality.

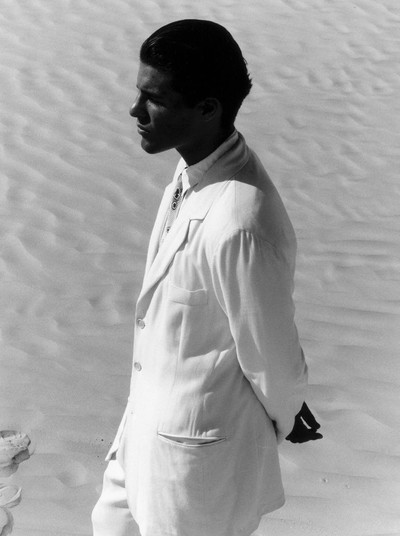

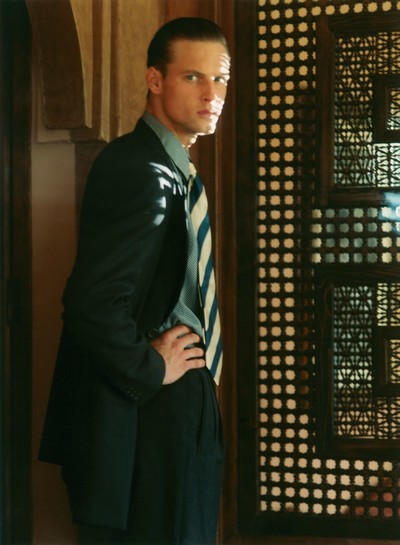

In the ensuing years, this reality was never better expressed than when Fallai’s bold photographs were blown up onto vast billboards. In 1984, one such huge mural, located on Milan’s Via Broletto, was prompting Italian men – and therefore all men – to reconsider what they thought about fashion, about their style, about their lives. Depicting four immaculately dressed men – real men, not simply beautiful models – their identical suits and ties the proof that the bedraggled 1970s had been replaced by a new era of mature mass democracy. While fashion (including that of Armani) may have since moved on, the aesthetic codes as defined in Fallai’s imagery remain as relevant today as they ever have. Indeed, a cursory glance at any men’s fashion magazine or seasonal menswear campaign will highlight the extent to which contemporary imagery is informed by Fallai’s sense of poise, composition and precision.

Talking to Aldo Fallai is a challenge. He’s not one to naturally want to theorise over the work he created with Armani. Even during the recent press conference for his retrospective book, Aldo Fallai: From Giorgio Armani to Renaissance: Photos 1975-2013, he remained shy and almost reticent to comment. We asked his friend, the veteran Italian fashion journalist Giusi Ferrè, to help him recall the period when he and Armani defined the codes that would change men’s fashion forever.

Giusi Ferrè: When did your working relationship with Giorgio Armani begin?

Aldo Fallai: It was around 1972 or 1973. Giorgio was still a young designer at the time; he didn’t have his own label yet. He was designing for a number of different houses, among them one from Florence which, if I remember correctly, was called Tendresse. I hadn’t even picked up a camera yet. I was a graphic designer for them, designing things like T-shirts and logos.

Weren’t you still involved in teaching at that time too?

Yes, I used to teach at the Istituto Statale d’Arte where I also studied. But I didn’t want to continue teaching because the world was changing so much. I didn’t know what to say to the students – they were all unemployed and not much younger than myself. I taught for five years then I quit.

‘The first time I met Giorgio, I thought he was quite funny. Everyone thought he came across as a pretty serious person but he knows when to laugh.’

You mentioned before that you hadn’t picked up a camera. Can you explain how that moment came about?

Sometime in the mid-1970s, Giorgio had been offered six pages of coverage in Vogue. I suggested that I shoot the story for him and he accepted. I bought a camera and started to learn about model agencies – two things that were totally new to me at the time.

What led you to the idea that photography was the ideal medium to explore?

I used to paint, I was a graphic designer and I used to take photographs for myself. I offered the creative knowledge I had to the designers I was working with to present their designs in the best way. In this instance with Giorgio, photography was the relevant solution.

What do you remember about the clothes Giorgio was designing then?

I was extremely fascinated by Giorgio’s designs, by his deconstructed jackets. But also, do you remember he designed military uniforms? It was such an exciting moment. I mean, who would ever think about dressing the army now?

Wasn’t that the spectacular shoot in Caserma Perrucchetti? I still remember looking at those photographs for the first time back in the late 1970s.

That’s right.

So, you started with Giorgio at Tendresse shooting women’s apparel?

It was not directly for Giorgio, but for the label he was working for at the time.

What was your first impression of him when you met?

I just thought he was quite funny. Nobody found him funny because he comes across as a pretty serious person, but he knows when to laugh. I always got along with Giorgio: we discussed things passionately, but we never argued.

Together you developed such precise image codes, particularly for his menswear. The Armani menswear aesthetic defined and ruled the era. Was it a clear vision from the beginning or was it something that evolved over time?

To be honest, it was unspoken; we never formulated anything specific. We developed it together step by step, as it came from simply observing what was happening around us.

For those early Armani campaigns, how closely did you and Giorgio collaborate?

It was totally collaborative. He used to be present for at least 80 per cent of the time – and I preferred to have him around. I tried to apply the working method Giorgio and I had to my work with other designers, but they didn’t help me. You know, Giorgio is very restless but that’s infectious. On the first day of a shoot we wouldn’t just take three pictures, we’d end up taking 70!

He’s still like that these days.

I remember one time we shot a full day and night without stopping. Gina Di Bernardo, the model, had 70 different types of make up done. The one that looks a bit 1930s is the same model – but she’s like a young Greta Garbo. I think those pictures are among the most beautiful we ever worked on.

You say that you preferred to have Giorgio around on those shoots. What else did he bring to the process?

I can say this: Giorgio is a perfect stylist, he knows absolutely everything there is to know – where to put the pins, how to place the jackets in the best possible position, how to shape the waistline.

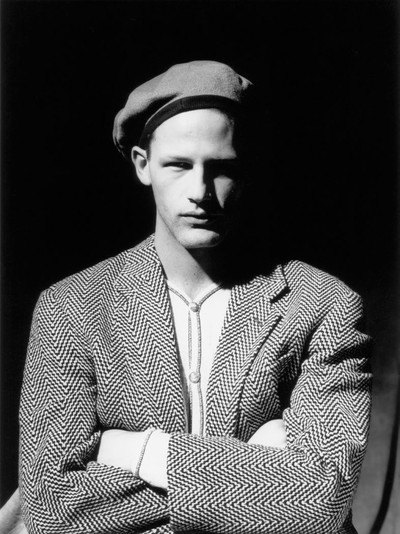

I was always particularly impressed by the image of the Armani man, because at that time he was going against the tide. In the mid-1970s there was a sort of ‘low-intensity guerrilla war’ taking place in Italy; groups of young people were engaged with terrorism, and that was reflected in the way they dressed. They were bohemian yet stiff, and a bit shabby. At the same time, Armani perceived a completely new type of desire. He grasped it, but he didn’t fully know how to express it.

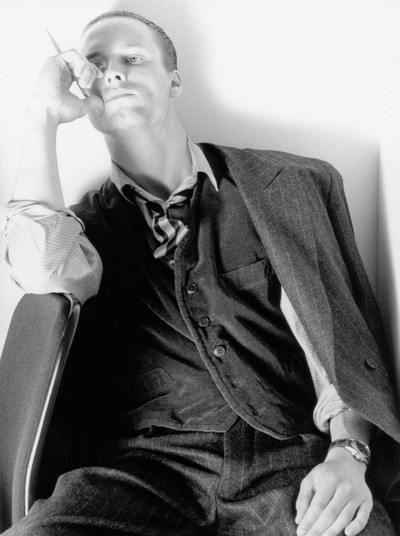

I think the key was the portraiture. All those portrait images we made look like they come from one single shoot. I recently had an exhibition, featuring all the portraits and I mixed them all up on purpose to prove this. As a body of work, the exhibition looked like the portrait of a non-existing Italian bourgeoisie – a sort of Nordic bourgeoisie, an enlightened bourgeoisie. Good people you could trust, who pay their taxes. A civilised population.

There definitely seems to be a strong moral element to these characters.

Actually, that was what we were all missing at the time. We were sick of Craxi-like people, of those thieves. It was a bad time, as it is now.

‘Giorgio is very restless, but that’s infectious. On the first day of a shoot we wouldn’t just take three pictures, we’d end up taking 70!’

Something that caught my attention was how meticulous and precise the image was, yet it came across as very sensual because of the clothes. They used to show the body without undressing it. It was sexy, but pure.

You’re right, and then there was also the narcissistic element of the person wearing the clothes, right? Showing off a bit. If you look closely at the images, the models are almost always looking straight at the camera – this was premeditated. Of course, there were images where they looked to the left or right but in the end we always chose the ones that looked straight at you. That’s the relationship between the image on the poster and the viewer. It looks at you and centralises everything. I remember when the first Armani billboard went up. It was a small, slow, low-intensity revolution of having black-and-white fashion imagery in the streets.

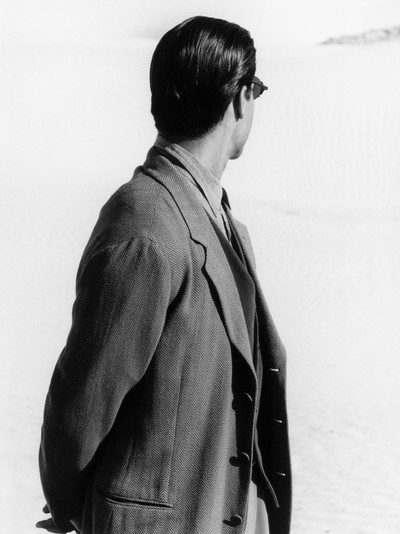

What was it in particular about black-and-white imagery that you preferred?

It’s like an abstraction, and it strips from the image everything that isn’t completely necessary.

I think Giorgio likes that a lot too, but then people around him at the company have maybe suggested using colour.

Yes, but from a commercial point of view. I mean, especially when there’s a period of general crisis, we should deliver dreams to people instead of helping to lower their general taste.

Indeed, that’s one interesting aspect of Armani’s aesthetics. I mean, there are two ways to present clothing. One is [Olivierio] Toscani’s sort of reportage, and then there’s something perhaps smore aspirational, like a dream both for men and women – I’d say that’s what you and Armani developed. It’s like a very subtle narrative of how we could be, and it’s highly seductive.

Yes, it seemed to touch people. I remember people asking when the next billboard was coming out because they missed those big sweet faces.

How big were those first billboards?

Forty metres high! The very first ones were hand-painted because there was no inkjet at the time.

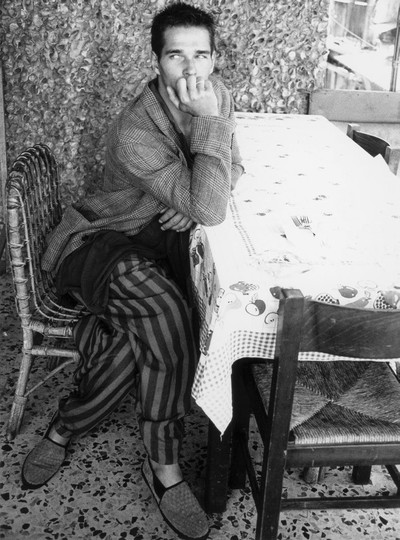

I still remember a specific campaign from 1988 featuring four men all wearing ties…

…and all wearing the same suit.

It was like a new form of democracy.

Unfortunately, over the years I threw a lot of my archives away. I did find parts of that campaign in the Armani archive, though. But not all of it.

How did you choose the models and faces of those four men?

Giorgio has always been really good at casting. I am also pretty good, but I’m not so good at picking women because I always end up getting influenced by some sort of personal fascination.

Were the men sourced from model agencies or were you street casting?

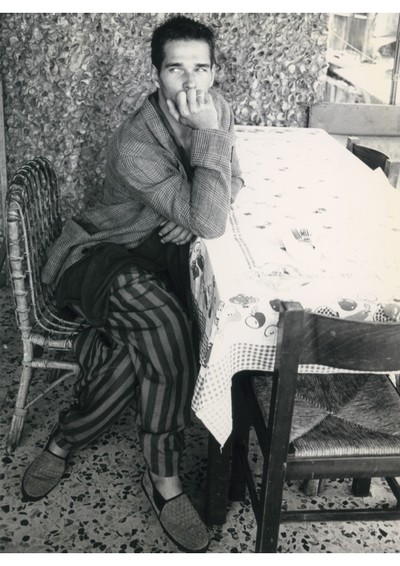

It was a mix: some regular guys and some models, but not the stereotypically beautiful models. They were all people with particular features, especially the Armani women. Antonia Dell’Atte, for example, had never modelled before: that only happened because Giorgio saw her in a restaurant. The same happened with Gina Di Bernardo. She was living in Milan, but she wasn’t working at the time. Giorgio transformed her into an icon because she looked wonderful in his clothes.

There seems to be a distinct 1930s portraiture reference in your work.

Yes, that and Renaissance paintings, where the figure is the central element in the layout. You cannot cut or crop it anywhere – it’s just as it is. The 1930s were also remarkable years in terms of fashion and photography.

The 1930s are obviously a sensitive subject for Italians. People were outraged when the mayor of Milan planned to organise a retrospective 1930s exhibition. It was perceived as the revival of fascism, though that obviously wasn’t the purpose.

Architects knew how to hide that though. Florence train station, which was designed by Giovanni Michelucci, is beautiful. Only if you look at it from a plane can you see that there’s a concealed reference to fascism – it hints at the fasces. It’s smart because Michel-ucci was not a fascist! He was obviously working within restrictions, but what he did with them was genius.

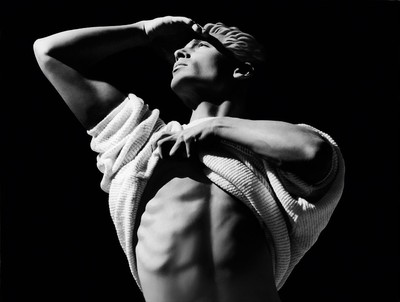

I do remember some beautiful architectural photographs you shot for an Emporio Armani campaign.

Do you mean the statues?

Yes, the statues. Were they inspired by the Foro Italico?

Yes. When we were working on that campaign, an issue of Franco Maria Ricci’s FMR art magazine came out and it was about those statues. Our main references were the Foro Italico and the Olympic Stadium [Stadio dei Marmi] where the statues were amazing.

Wasn’t this the campaign where the guy has blond hair?

Yes, and those images are retouched by hand with a paintbrush.

He looks so much like a statue, that’s amazing. It is still impressive after 30 years. I know that a lot of photographers use it as a reference for sports imagery. A lot of people go back to those photographs because there was something very heroic about those men. They were the perfect fit for Emporio, which was the line Armani had designed for a younger customer.

At that time many designers used to make collections inspired by the latest successful movie.

‘I remember when the first Armani billboards went up. It was the start of a slow revolution of black-and-white fashion imagery in the streets.’

Yes, I remember when Out of Africa came out: that’s when I realised the influence of cinema on fashion.

Although we used FMR magazine as a reference, any other events around that time could have also been the source of inspiration for a collection or a campaign. Why not?

I get the impression there was less narcissism at that time with the designers. It was more common for them to be inspired by external events.

Yes, at the end of the day they are just designers!

So let’s talk about your studio. Was this based in Florence at the time?

No, in Milan. I used to have a studio in Florence as well, but it was nice to have a break, go to Milan with my suitcase, work and then leave. I also used to work on Emporio Armani magazine with Rosanna [Armani, Giorgio’s sister]. She also modelled for me and Giorgio.

She was so pretty. Was she good at giving directions on his behalf?

It’s not a coincidence that they are siblings! She is tough and very demanding. I do miss that, actually.

Do you know what? It’s sometimes complicated to work for Armani but also easy once you grasp his aesthetics and his concept.

Right, but I can tell that not everybody has managed to grasp that!

Did you approach your work for Giorgio Armani and Emporio Armani differently?

To be honest, it didn’t really make any difference to me. I guess you could say that one type was more the one you meet on the street and the other the one you would like to stop on the street!

I remember the controversy when they decided to call it Emporio. Everybody was against it as the word had connotations of something mass market! Anyway, Armani always took such extreme care about his campaigns because the aim of those images was to represent his entire brand concept. It was never simply a matter of presenting a dress or a suit; it was about communicating who is the man wearing that suit and what is his entire world and environment. I believe that’s a different aesthetic model.

Along with the campaign, there was always a book, which people liked. At that time the brand communication encompassed an entire way of living.

This has always been one of Armani’s trademarks and it’s still recognisable. If I think about his interior design, he likes to define the world he imagines and where he thinks you could be integrated in that world.

Yes, I think that’s a key trait.

But sometimes his life must have been terrible, right? I’ve always thought of him as one of those people who suffers if everything is not perfectly in place.

It’s funny you say that because he always allowed me to smoke. Even though he wasn’t a smoker himself, he never told me to put my cigarette out. But as soon as I’d finished my cigarette, he used to personally empty the ashtray! Himself!

That’s great! This is such a unique trait for people to understand. Armani is one of the few designers who invented and created this precise style.

Yes, it was a precise style of dressing, of living in a specific house, of going to a particular hotel.

You worked with many other clients. Did you feel the difference?

I collaborated with pretty much everybody: I did some work for Valentino which remains anonymous, two or three campaigns for Calvin Klein… I had a lot of clients, except for Versace and Dolce & Gabbana as that would have been a conflict. And yes, I noticed the difference. I genuinely loved the style of Armani and I personally dressed that way. Before meeting him, I used to wear second-hand clothes that I’d bought from the local market.

We talked before about the strong moral element that the Armani man embodied. Those faces and those looks also represent a real sense of health.

Yes and nowadays young people in their twenties don’t know that kind of look. When I was in Florence for my exhibition, I saw students drawing the jackets. Can you believe that? The guys wear such tiny jackets now!

They look like kids’ jackets, right?

I’ve noticed men in London and Paris wearing black leggings or tights.

Armani was the designer who launched large trousers. Do you think there’s an element of him referring to the memory of his father?

I always thought about that.

In his womenswear, there are references to his mother, her spirit is in there.

Yes, I agree. I used to know his mother pretty well.

She was a wonderful woman.

She was great! His father was a very elegant man. He always wore a gilet and I’ve seen pictures of him wearing a creased white suit.

Giorgio once told me his big regret was that hadn’t known his father well.

Yes, because he died when he was young. But there are many pictures of him around.

He said that he never paid that much attention to his father and that he later understood that he’d ignored so many details about the man. He remembers him fixing and cleaning his watch, as his father loved vintage watches. I think this is a beautiful memory, and I’ve always thought that in his menswear there’s a bit of his father.

Yes, there’s a certain softness in the image of a linen suit with the gilet.

Another thing I was curious about is the incredible success of American Gigolo, which helped launch the Armani man worldwide.

Yes, that was the trigger for Armani’s international expansion in the 1980s. A movie like that was the perfect platform, and Richard Gere looked a bit like one of the Armani models.

‘The success of American Gigolo was the trigger for Armani’s global success in the 1980s. Richard Gere looked and walked like an Armani model.’

The way he walked was very Armani. Richard Gere has always said that he owes the launch of his career to Armani. There was something in the American Gigolo masculine image that was interesting, and it was the perfect introduction of Armani’s jacket, his trousers, his shirt.

It was a very neat and precise look. I remember being really impressed by that image at the time. Although to be honest, when I look at it now, it seems rather flat and a bit too American.

Can you remember any other cinematic influences you recognise or consciously referenced?

If you watch Fellini’s I Vitelloni, you can see where the Armani style comes from. He was probably still in his teens when that film came out.

It’s interesting you say that because that style has always had a huge impact on him.

Giorgio developed the men’s waistline, which is something nobody was doing before. The waistline became wider by going higher. He revisited – and made fashionable again – the shape designed by Yves Saint Laurent.

Your collaboration with Armani lasted many years, until the mid-1990s, right?

Even after that. I also shot some collections a few years ago. We’ll maybe do something else together in the future.

Do you often stop to think about the work you created together? And the aesthetic you developed?

No. Fellini used to say that films should never be explained. I am sure that if Giorgio and I were to discuss this now, we’d agree on the past. At the end of the day, we both knew we were making a bit of history.

Finally, there are many great photographers nowadays, but when you look at the campaigns they shoot you rarely think, for example, ‘Ah! That’s a Calvin Klein campaign!’ You always end up thinking, ‘Ah! That’s Peter Lindbergh’. When you look at an Armani campaign, though, it is Armani, and it comes from this collaborative process that dates back to those first shoots. This is what makes the difference.

In my opinion, fashion advertising campaigns will never have their place in what I consider to be fine-art photography, a medium that is based on the notion of exhibiting photographs. This is the world of someone like Cartier-Bresson for example. Nonetheless, photography can be highly effective and emotive when used in collaboration with other environments and mediums. And this can sometimes be the case with photography and fashion – it is fine arts applied to industry.