Juergen Teller goes back to school.

By Hans Ulrich Obrist

Photographs by Juergen Teller

Juergen Teller goes back to school.

Much is made of Juergen Teller’s seemingly unique place in the world of photography. Blurring the lines between commercial and fine-art pictures, his ad campaigns hang in museums while his eye-popping self-portraits end up promoting luxury brands. Juergen’s is a topsy-turvy world, one that happily eschews the conventional wisdom that Art shouldn’t be dirtied by commerce and that commercial assignments only function with ‘commercial’ imagery.

At the beginning of the year, Juergen excitedly shared some news with us. He had branched out into an entirely new photographic activity: teaching at Nuremberg’s Academy of Fine Arts. He’d already got his students shooting a number of Teller-esque assignments – a nude, food, your street, your parents, animals. He was genuinely thrilled by what they’d come back with.

And then came the idea.

If his presence as a teacher could have any real influence, the students’ work would need to get fast-tracked into a ‘real’ environment. One that might introduce these images to the people who decide what goes in magazines, fills gallery walls, sells luxury clothing.

The students’ photographs, Juergen suggested, should be published in System.

Of course they should. Primarily, because much of the work shows promise and is worth sharing. But also, by accepting Juergen’s request, we’re furthering his own blurring of what should and shouldn’t be done in fashion photography. We’ve been willfully kidnapped. It’s a kind of photographic Stockholm syndrome.

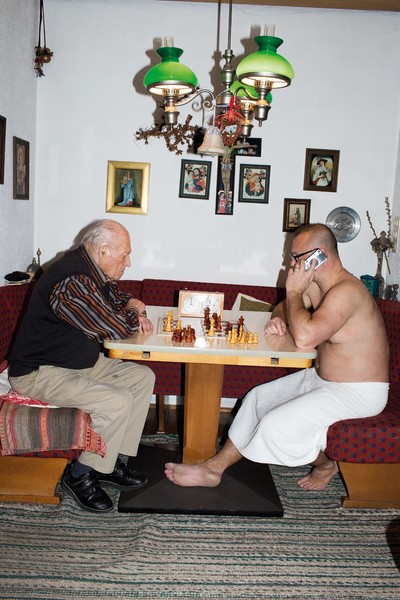

What’s more, the following conversation between Juergen and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist convincingly puts forward the case for teaching – or at least sharing one’s experiences. And then there’s the wonderfully giddy portfolio of Juergen’s own pictures of the students and their school. So deliciously upbeat, so infectiously fun, they represent the best university prospectus you’re never likely to see.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: Let me just turn on the second recorder. I always bring two just in case one doesn’t work.

Juergen Teller: That’s how I work too. I always have two cameras.

I recently interviewed Jeanne Moreau. She came to the interview with full make up and with her hair done and expected me to bring a photographer along. There had been some sort of misunderstanding. After the interview she asked, ‘Où est le photographe, où est le photographe?’ I couldn’t let it end like that, so I told her, ‘Madame Moreau, I always do the interview and the photograph’ – even though I’ve never done portrait photography in my life. Then she directed me through the shoot. ‘Higher, higher, left, right.’ I thought about that this morning, because it was about teaching and transmission of knowledge. Are there any rules for doing portrait photography?

No, actually not. The only thing that’s important, is that you capture the person as good as you think is possible, that you get into their psyche – who the person is themselves. Sometimes it takes a long time, and sometimes it is rather quick. You have to quickly understand their gestures – how they drink coffee or how they hold their hands. You have to recognise this right away. I also think that because I’m so open, it makes people feel more relaxed. Then of course it is also about the way I actually take pictures: I don’t use a camera stand, so the subjects aren’t frozen on the spot. And they become more at ease and more comfortable the more pictures I take.

When you took my portrait, I noticed that you used a flash and were clicking what seemed like a hundred times. Then there came a moment when I just surrendered.

Exactly.

So that is an element of your technique: taking as many pictures as possible. And with two cameras.

Taking as many pictures as possible would be too simplistic – it’s a bit more complex than that! Sometimes I only take a few. But by taking many, I seem to relax the subject and myself.

‘Taking as many pictures as possible would be too simplistic – it’s a bit more complex than that! By taking many, I seem to relax the subject and myself.’

Do you actually use both cameras at the same time?

No, not at the same time. It is one time like this and then the other time like that [Juergen shows the way he holds the cameras.] And then I sneak up like an animal.

One in the right hand and the other in the left?

Exactly. But I’m always looking through the viewfinder. When I take a picture with one camera, the flash on the other is charging. And then of course if one of them breaks, I have another one spare. Normally, I have a third one in my bag.

But you look through here, you click and then you look through the other viewfinder.

I’m always looking through.

Do you have an assistant? Does he also press the button?

No, never.

What does he do?

When a film’s finished, he puts a new one in, or reloads the batteries. And he’s the one I talk to about the shoot when the subject goes off to the bathroom! It’s always good to have someone to discuss with and to make sure the light is good or whatever. He helps overall, so it all goes faster. Now that I use digital sometimes, I only use one camera; you can see on the back whether it’s technically OK.

Do you have any rules with the light? Backlighting for example?

No, it’s always specific to the moment – what’s good for one person. Sometimes daylight is better. Sometimes when I’ve visited the location before, on the day of shooting, the weather is totally different, so you have to rethink it. Sometimes you have certain concepts of how you want to shoot and then it just doesn’t work out, and you don’t know why. Then you need to fairly quickly redirect what you would think ‘right’ is.

You have to be able to improvise.

Yes, that is very important. And of course it’s like that when you have to take someone’s portrait at their house – you have to familiarise yourself with their surroundings very quickly. Sometimes you stop and drink a coffee. Like when I photographed David Hockney: he just sat on the sofa, smoking a cigarette, and we talked about something completely different. And then I said stop, and I got out my camera and took the photo – we didn’t need to go into the studio to shoot.

So it often develops into a conversation. But unlike my own conversations, they are never recorded. Henri Cartier-Bresson, who took pictures of all the great artists of the 20th century such as Giacometti, Bonnard and Matta, told me that they had conversations for hours which were never recorded. They were all compressed into a photo. Was it similar with Hockney?

I got there by train, and he picked me up from the train station. He was waiting with a cigarette and a lighter in his hand and said, ‘I remember you smoke.’ He gave me a cigarette and lit it for me. We then drove around in his Audi Cabriolet playing extremely loud opera music. ‘Vroooom.’ First, we went to his studio where I took some images, then he invited me over to his house.

Tell me, have there been times when a portrait hasn’t worked out at all?

Yes, of course. What then happens depends entirely on your courage to call them up and ask for a second try. Nowadays it’s getting harder, because people are in the habit of taking selfies which they can retouch by themselves. People are becoming increasingly vain.

How? In what ways?

Just by looking at all the stories you see in magazines. Every photograph is retouched, and everyone expects that. But I do not do that.

‘It’s getting harder to take portraits because people are taking selfies, which they can retouch themselves. People are becoming increasingly vain.’

So there are problems with the models?

Not so much with models.

But?

Well, with actors, for example. Then, there are those actors who don’t want me to photograph them at all, so it just wouldn’t happen in any case. People know by now who I am and what they’re getting into with me. Likewise, I’m not interested in photographing them either. It’s just exciting if both parts want to work together.

Are there any exceptional poses or unrealised things that people don’t want to do for you?

No, actually not.

But things like this [shows an image from the Vivienne Westwood nude series], is this your idea?

This came from her. I’ve known her for 15 or 20 years. The pose, sitting with open legs, this came from her.

So you stripped her bare?

Well, you should know that I’ve shot her fashion campaigns for the past five or six years. I always thought that the best spokesperson for the brand would be her husband and herself – not some young models. It’s totally outstanding what she creates. I’ve always been very enthusiastic about her: what she stands for politically and what she is doing.

What about her actual look?

I like the whole story: her orange hair and her pale skin. And then it came to me that I wanted to photograph her nude. She looked at me for quite a while and said that it was something she’d never been interested in doing. But then, she was curious about how it might look. So she said I should come over on a Sunday afternoon, and we’d do it.

But it was your idea?

Yes. And she just sat full-frontal right from the start, and I thought, ‘Wow!’ I thought she might start sitting on the sofa in a ‘regular’ way, but right from the beginning she sat like that. Later on we shot from the side, but the first one was this straight-on shot!

But it’s not like you give any direction.

No, I did. I asked her to show me the house, and we would take the photos on the sofa. I realise if it works while they are posing, or I guide them there. I guide them because I think it’s right.

So it is not really instructions but rather some kind of guidance.

Yes, we go somewhere together.

And how did it all begin? I was thinking that I never studied at school what I am now doing. I studied economics and ecology, because I was interested in how to change the world through its systems and all that. Everything with art, though, I learned by myself. Fischli/Weiss and Gerhard Richter were my mentors. There was always this kind of mentorship. I always thought that I could never really teach – all the bureaucracy would be so different from the rest of my work. My mentoring role is that I work with young people and curate exhibitions with them. This is better than teaching in a school for curators. I wanted to ask if this is similar for you?

I actually studied photography at the Bayerische Staatslehranstalt; I only learned technical skills though.

Such as?

How to handle large-format cameras. How to take pictures of churches in a particular way, so the angles won’t be off, and everything is straight. How to develop black-and-white and colour films… All the technical stuff. Then I went by myself to London in 1986 and I started to photograph record covers for people whose music I liked. My visual education came from TV and record covers I saw when I was young. I always thought that when it was a good record cover, the music must have been good as well.

Which ones did you shoot first?

Cocteau Twins, a Björk single, New Order… Then I went on tour with Nirvana, that was in 1991. I took pictures of Elton John and Simply Red – that’s when I made some money.

And what triggered the desire to now teach? Where do you do that?

It’s the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Nuremberg… for some reason now, I want to be a professor. Now that I’m 50 years old, I was eager to do it. When I’m there, I stay with my mother, who is only 35 minutes away from the Akademie. It’s in a wonderful Bauhaus building situated on the edge of the forest – like where my mother lives. I gave a lecture there once, when I had an exhibition at the Kunsthalle in Nuremberg. In the morning, my mum drives me to school. And in the evening, I take a taxi back home.

There is also your well-known book, Nürnberg. I love that book.

About the teaching, I just thought to myself, if I don’t do this now, I never will. I’ve become a little bit bored by the world of commercial photography; I’ve achieved quite a lot in that field, and I know what I am doing, know how to work with clients and so on. I wanted to do something different, just to see how something different works. I was able to select my students – I now have 22 – and it’s a lot of fun to work with them.

‘When I’m in Nuremberg, I stay with my mother, who is only 35 minutes away from the Akademie. In the morning, my mum drives me to school.’

How do you structure your workshop?

First, they showed me their portfolios to see what they are doing. Then we talked a bit about it – what I thought was great, what they could change in their layout for example – and then, right from the start, I started giving them various assignments. They have to take a self-portrait, an iPhone photo, a female nude, a male nude, their house, a series of 12 photos of the street where they live, five photos of animals, and then three of their favourite food.

Sounds like something Hans-Peter Feldmann would do…

… and I also want a funny photo, a portrait of their parents, one or a series of fashion photographs, a portrait of their professors, and as we are right beside a forest, I wanted them to photograph that too. I didn’t want them to sit around studying books; I wanted them to get started and keep themselves busy.

It was a whole catalogue of work.

They should be engaged with their surroundings. I was extremely happy and surprised with what they have done. That is why I called System and told them that it’s so great what the students are doing and that they should turn around the ‘system’ and let me show a portfolio from the students.

How old are the students?

Between 22 and 34.

At the Serpentine [Gallery], we’re currently doing this project with Simon Castets the French curator, called 89plus. We are mapping out a new generation of artists all born in 1989 or later, after the fall of the Berlin Wall. They’re the first generation that grew up with the internet, when they were six or seven – and that makes a huge difference. We’re researching 5,000 portfolios. Maybe we can work together with your students? Do you think the internet has made them work differently to you?

Yes. They take pictures with iPhones and embrace new technology. I think it’s great. But that being said, a lot of the students shoot analogue, not digital.

The artists taking part in 89plus are all unknown – it’s like this Warholian idea of The Factory, giving them a platform. We also convinced Google to give grants. It’s similar to you and the rest of our generation: we’ve been helped, now it’s time to give something back.

For me that’s the whole point. A student told me, ’Do you realise that what Eggleston was for you, is what you now are for me?’ I never thought that I’d have so much fun working with younger people.

Is it the break from the routine of what you normally do?

Well, much of the time I’m working in serious commercial businesses. Of course, I have exhibitions in galleries and museums, but when I work for Marc Jacobs and now for Louis Vuitton, the further into it you go, you realise that slowly we have grown up. It’s serious business. What I like most about the students is that they are not cynical in any way; they are incredibly naive and just have a lot of fun photographing – they only start the thinking and analysing afterwards. I also like the fact that I’m not teaching in Paris, New York or London, which people already know are established teaching places. Nuremberg is ‘clean’ from all this – this is what is so fun. One assignment was to create a fashion photo or series. This young woman said, ‘This morning, I went to the train station in Nuremberg and bought a copy of French Vogue to see what they’re doing.’ She tore out a few pages and recreated those images as self-portraits. [Shows Hans Ulrich the student’s work.] This is based on a fashion editorial by Inez van Lamsweerde. Isn’t it fantastic?

This is great. What is her name?

Claudia Holzinger. The next one was a fashion brand where she had to choose all the clothes. [Shows the work.] That is excellent, no?

‘When I work for Marc Jacobs and now for Louis Vuitton, the further into it you go, you realise that slowly we have grown up.’

That’s really good! Have you found that there are certain common themes or interests in the students’ portfolios? What astonishes me the most with the 89plus project – which is something you’ve actually successfully been doing for many years and is now common practice – is the sense of parallel realities. When our generation started out in the late 1980s or early 1990s, you had to decide whether you wanted to be a curator or photographer or artist or someone who works in advertising. These boundaries or divisions were still very much in place. So photographers would have to choose between fashion photography or art – you couldn’t just be a photographer. With the internet, these boundaries have completely dissolved. The whole 89plus generation have three, four or five different careers – just like you. On one side you are an artist, and you show in museums and galleries around the world, but at the same time you are also a fashion photographer, and a chronicler or portrait photographer rather like Snowdon. This approach seems very relevant nowadays with younger people, where everything is equal and can exist simultaneously.

I want to take my work over to Nuremberg, so they can see how I work. I will definitely do a fashion editorial or ad campaign there and have them involved. I want them to photograph me, and I will photograph them.

You want it to become reciprocal.

Yes, and it will develop. And in the end, I hope to make a book with Steidl together with them.

Doing this in your ‘homeland’ also strikes me as significant.

You are right. That is important for me. Doing this at another art academy would be strange. This is why it is so much fun. And my mother is not getting any younger, so it’s nice to be able to see her more often.

It could be part of the project to photograph your mother — that would also be interesting.

Yes, they all wanted to see my mother, as I’ve photographed her quite a lot over the years. One evening I went out with the students for food and drinks and we all stayed out quite late. The following day at 11am, I came into class with my mother, but none of the students were there because they were all completely hungover. [Laughs]

Coming back to your method: the two cameras, you don’t use lights, it is improvised, it is individual. When you assigned the homework, did you give the students hints about how to take photos of a street or an animal or how to develop a fashion editorial?

I only gave hints after they showed me their first assignments, like if I thought they should rework or redo something. I’d say, ‘Don’t be lazy.’ When there was something good or not so good, or something I totally didn’t understand, or that they should concentrate on this or that. That’s how I would give tips. And of course we would discuss what is good or not.

Can you give me an example of how you would critique?

I was there for two days and spent the entire time looking through their work. Afterwards I was completely exhausted. Initially I thought, I could do more. But there was so much stuff. But what was good is that the students discussed the work of others. Everyone observed and watched.

It was a collective process. I am really interested in what one can concretely say about the process, because I think that art cannot be taught.

That is a good question. As I’m not going to be there for the next three and a half weeks, I sent a FedEx box with my rare photo and art books – like Gerhard Richter’s Wald – for the students to look through. But what I really want to teach, or rather what I hope to achieve, is that I use my own energy and enthusiasm for photography to help develop their enthusiasm. I want to encourage them to want. From the beginning, I told them their work should be about loving life. It shouldn’t be so much about the photography. To take photos, you have to love life – then you can photograph anything.

Do you think it’s possible to teach enthusiasm?

Yes, I really think that is what it is all about.

‘From the beginning, I told them their work should be about loving life. To take photos, you have to love life – then you can photograph anything.’

I’ve always thought that enthusiasm is my medium. I totally believe in enthusiasm. Energy and enthusiasm.

That’s true. You have to have fun or you won’t get anywhere.

Actually, you could say that you are a transmitter of enthusiasm.

I really noticed that about myself. Let me show you another example which hit me like a tonne of bricks when I saw it: the student who photographed herself in the fashion story also photographed her mother and her father where they live, deep in Bavaria. It’s a series of five or six photos of her father standing in the corner of his living room, wearing his slippers. Each year his family give him a new Bayern-Munich outfit. These photos turned out excellent, and I’d be really excited to see them published somewhere. I can’t help but be enthusiastic about them. So if I manage to get the students’ portfolios into System, I can do something that other professors perhaps couldn’t: I want to bring the students straight into the ‘working world’ – which they’re obviously really excited about.

That is exactly what we’re doing with 89plus. We take people that don’t have galleries, who don’t have representation or who haven’t exhibited yet and take them into the active art world. You as an artist and I as a curator have this platform which we can pass on to the younger generation now.

Exactly. That was the idea. They are so excited.

It is exciting. It’s the first chance to show their work.

Instead of a self-published book or on the internet.

It’s direct. It’s like a highway to magazines or into Jumex or the Serpentine Gallery or wherever.

It’s a lot of fun to bring so much new energy into this.

I’ve had so many mentors of my own: Fischli/Weiss and Gerhard Richter gave me so much, transmitting their knowledge as a school of seeing…

In your case, it was very early.

Yes, I was only 16 or 17. I was bored of my own surroundings in Switzerland and I was looking for these people as an escape. I had a professional mentor, Kaspar Koenig, when I was the same age as your students or the 89plus kids. He said he would like to create exhibitions with me – I was the co-curator, and he really was my mentor. Was Eggleston your mentor?

Yes, but I got to know him quite late on.

How did that meeting happen?

I was asked by Art+Auction magazine to photograph Eggleston in Memphis. We got along very well, so after three days he came with me in the taxi to the airport and told me that he wanted to do a road trip with me through Bavaria. I thought, ‘This is Eggleston! He is God! Is he being serious?’ Two weeks later, both with a camera in our hands, we were driving through Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Did you make a book of that work?

No. We just drank, smoked, talked and ate Leberknödelsuppe. Both of us had the same Contax camera around our necks, but neither one of us took a single photo. I didn’t want to push it, because we were going to see each other again. And we did do things together.

So this was the first encounter.

The second after Memphis.

You discussed a lot together. What have you learned from him?

To be free. I mean, I’ve never met a person like him before. He really is so selfish, he does only what he wants to do. It doesn’t matter, whether it is day or night or whatever anybody thinks of him.

He never does what he is obliged to do.

Yes, he just does what he wants and that was amazing to see.

Emancipation.

Yes.

Did you get any tips from Eggleston?

We talked a lot about photography but never about the technical issues. More about other photographers, book design and so on. I had an exhibition in Tokyo in 1991 at Parco department store. It was strange at that time that they had these exhibition spaces in departments stores.

Yes, I remember. My second trip to Japan was with Gilbert and George. They had a huge retrospective show with Anthony D’Offay in a department store. It was crazy, that was the late 1980s.

In my case, it was 1991. A Japanese friend called Satoko asked me to go to the opening of the Japanese photographer, Araki. At that time, no one in Europe knew Araki. I went and it shocked me. The architecture of Tokyo is totally different, and somewhere in the middle, you have this no man’s land, fenced in. There were these hills of sand, and Araki had this open-air exhibition. He printed the photos on metal or cardboard and stuck them into the ground or nailed them onto the fence decorated with flowers. And in the middle of all this he was taking photographs. I have never seen anything that wild. And now we’ve actually just done an exhibition together, Araki and I, in Vienna at the Ostlicht Gallery.

Have you ever done a joint exhibition with Eggleston?

No.

‘Eggleston and I just drank, smoked, talked and ate Leberknödelsuppe. We had the same Contax around our necks but never took a single photo.’

Is that an unrealised project?

Yes, it is. In the book, Araki writes about me and I write about Araki. The book is over 400 pages long. Could you read this please? [Shows the Araki text.]

That is the story in the department store. It is interesting, because you are describing an ‘energy bundle’ that is frenetically, almost hysterically, taking photos nonstop. That relates to enthusiasm, which we talked about earlier. What is the ‘Fucky Fucky’ thing?

The Fucky Fucky thing is: We got invited for drinks afterwards, Araki zoomed straight towards me and then to Satoko, pointing his fingers at me and then to her saying, ‘You and you, fucky fucky.Me taking pictures,’ and kept repeating, ‘You and you, fucky fucky, me pictures.’

Really?

Yes, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I mean, I was so young and still green behind my ears, it totally freaked me out for months afterwards.

And he would have taken photos?

And he wanted to take photos.

An unrealised project.

Exactly. It’s obviously something that we could never have done, but in retrospect, I would have been quite keen to see the pictures. [Laughs]

That is unbelievable. Who is that?

Leslie Winer. She was a famous model in the 1980s. Araki shot in black and white, and I shot them in colour. He takes a lot more photos than I do.

But you also take a lot of photos.

Not as many as he does.

How many photos do you take per shoot? Do you keep them?

Yes, they are somewhere.

How are they archived?

On the computer.

In the digital cloud.

Yes exactly.

That is a fantastic book.

It is quite intense.

Fantastic. It is wonderful that Araki’s work is in black and white and yours in colour. They compliment each other very well.

When I saw them, I thought about taking black-and-white photos as well, which I havn’t done for a long time.

Felix Gonzales-Torres always said that black and white is the resistance to a world of colour.

I photographed black and white in the early 1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s. Then I thought the world is in colour. And since then, I’ve only photographed in colour. Now when I see Araki’s photos, I think black and white has a certain incredible power.

We are not used to black-and-white images any more.

You’re right.

The book is extensive. [Flipping through the book.] What is this here?

That is a low-res scan. Those are my two assistants in Frankfurt in a sleazy hotel near the train station. This one is my assistant, my business manager and me in a dodgy bar near the train station. And this picture is called Betriebsausflug.

That’s a great picture, it almost looks like Leigh Bowery. Let me tell you something that Araki once told me. He said that Vienna is the city of death.

Vienna? True, no?

[Quotes from the book:] ‘Photos must face life, as indeed his (Juergen’s) do. Whereas inevitably death gets into my photos. I think Juergen is in the period of the active volcano. He continues erupting. I am Mt. Fuji (the dormant volcano) but something is always burning inside of me to erupt. Photography is all-inclusive. We can shoot anything, whatever interests us. I feel this book may be something special. The composition shall be able to realize that one photographer’s work makes the other’s photography look much more intelligble and fascinating. The moments of the present spill over from this book. These are here-and-now photos. This is now. This is photography.’ Wow, that’s beautiful…

It’s quite nice, no?

Do you think you’ll continue teaching?

I’m doing it for one full year. I didn’t want to make a long-term commitment. But who knows, the way I like it at the moment, I might carry on.

‘Araki zoomed straight towards me and then to Satoko, pointing his fingers at us, saying: you and you, fucky fucky, me taking pictures.’

The question is, why are there are no schools out there that we’d consider a Black Mountain College – somewhere that magnetically attracts us? Black Mountain College would be a place where Rem Koolhaas would teach, or Daft Punk, or you and I. All disciplines would be together. We do not currently have that. The question is of course, should this multi-discipline school exist? Is it missing?

Good question.

Rilke wrote a wonderful book, Letters to a Young Poet. What advice would you give now, in 2014, to a young photographer?

As always, wie immer: Be enthusiastic.