Just this once, Karl Lagerfeld looks back

at his earliest inspiration.

By Hans Ulrich Obrist

Illustration by François Berthoud

Just this once, Karl Lagerfeld looks back

at his earliest inspiration.

In a career spanning half a century, in a world whose most celebrated inhabitants are known by their first names only, there has only ever been one Karl. For many, Karl represents fashion. He’s the embodiment of its evanescent enigmas, an icon who revels in the creativity found in its contradictions. He’s a designer who loves to draw, yet doesn’t keep hold of any of his sketches, though he owns thousands of books of those by others. He’s someone who designs homes and hotels, yet lives and sleeps in the Paris atelier where he works, resting for seven hours each day at the most. Someone with a lifetime contract with two fashion houses, who designs over 20 collections a year, yet has never employed anyone other than a maid. In the third of Hans Ulrich Obrist’s interviews for System with those fashion designers for whom ripping up the rule book and writing their own comes as naturally as paying ‘homage’ comes to others, the Swiss curator met Lagerfeld in Paris, just days after Chanel’s much publicised supermarket show.

Hans Ulrich Obrist: It all started with a coincidence?

Karl Lagerfeld: Yes, I won a worldwide competition that was organised by the International Wool Secretariat. There were about 200,000 competitors, and I won the first prize for a coat I designed. The coat was reproduced by Balmain. I went for the fitting while I was still at school doing my Abitur.

Pierre Balmain asked me whether I would be interested to work in his studio. I asked my parents, and they said that if it didn’t work out, I’d still be able to go back to school. I stayed there for three and a half years, and then I left to go to Patou. I never went to fashion design school. I am totally self-taught, an autodidact.

Painters and sculptors have a catalogue raisonné. Gerhard Richter says that all of his works are early works up until number one of the catalogue raisonné. So where does your catalogue raisonné start?

I can reply to this once I stop and I am dead. I am never content, I always destroy what I do, I do not keep anything. I was born with a pencil in my hand and have been drawing all my life. I was always interested in paper and pencil, reading and learning languages – that was what I was interested in. I did not care about the rest.

‘I was born with a pencil in my hand and have been drawing all my life. I was always interested in paper, reading and learning languages.’

What were your early drawings like?

Mostly I was looking at a lot of picture books at that time with historical costumes – no children’s books. Illustrations or drawings of women from Van Dyck or Rococo illustrations. I remember one year when I did an exam, I illustrated my work with fragments from a drama by Hofmannsthal, which was never staged. I didn’t only write it, but I also illustrated alongside it.

What was your relationship with art early on?

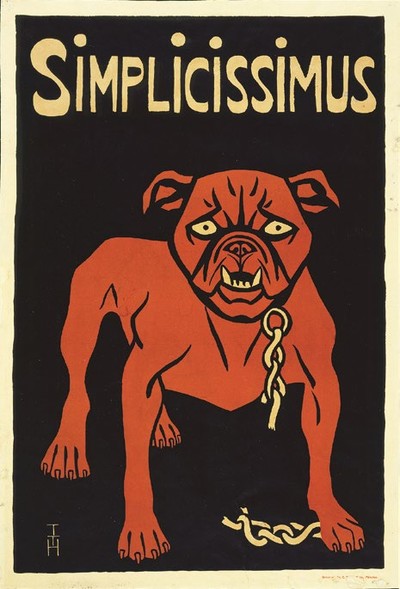

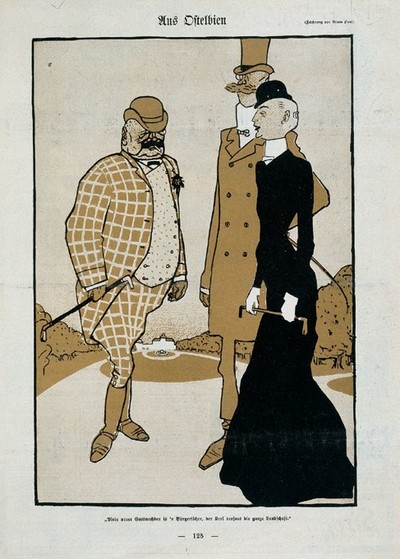

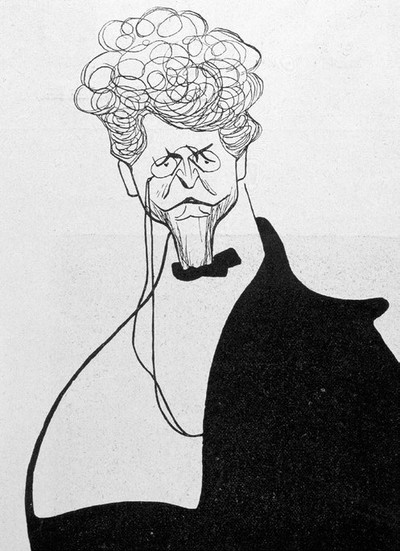

When I was a child, I found a rare pre-First World War edition of Simplicissimus [a satirical German weekly magazine] in the attic, which I still have and which is quite unusual. Inside there are all the caricaturists from the time. Every drawing was an artwork in itself. The ones I liked the most were those by Thomas Theodor Heine and the Norwegian, Olaf Gulbransson. For me Gulbransson was a genius: with one stroke he could say everything. Unbelievable.

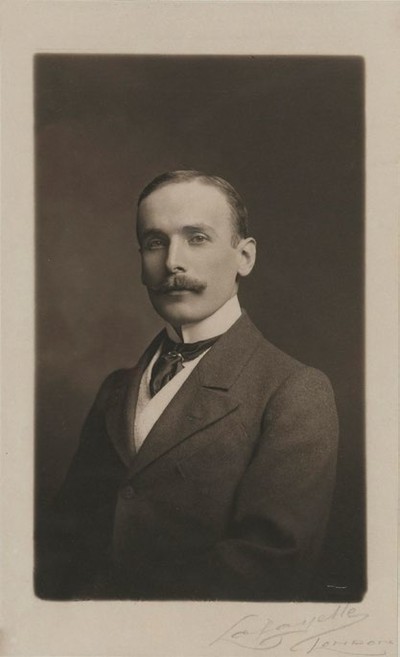

And Thomas Theodor Heine?

He was one of the founders of Simplicissimus. He was a very good illustrator: a social critic, and at the same time really detailed in his drawings. His works were some of the most commonly printed sketches in Simplicissimus, along with the works of Eduard Thöny and Bruno Paul.

Tell me about Bruno Paul.

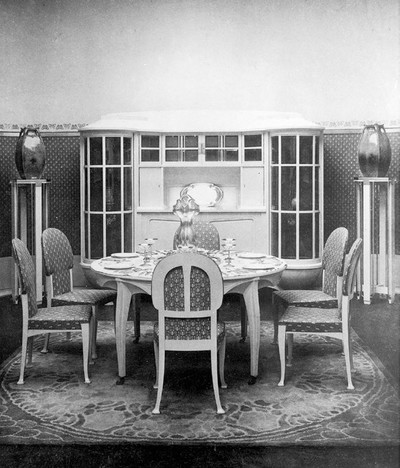

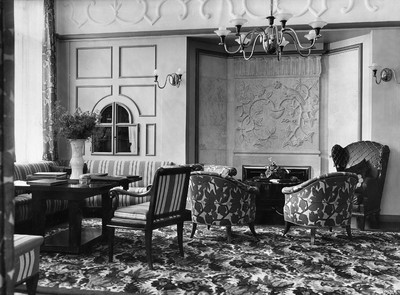

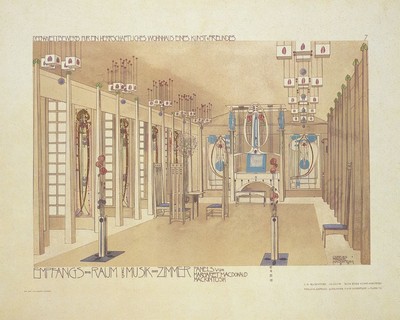

Bruno Paul was a fantastic and famous caricaturist but a totally different story. It was impossible to find his original sketches because the Nazis destroyed the Simplicisimus archive. There isn’t anyone else like him. After Bruno Paul left Simplicissimus, he became the director of the Deutscher Werkbund [The German Association for Craftsmen] and then later became an architect. The Deutscher Werkbund pre-dated the Bauhaus: it was a modern design organisation, but more luxurious than Bauhaus.

What was Bruno Paul’s design and architecture work like?

The furniture he designed was so luxurious. I have a house that is furnished entirely with Bruno Paul furniture from before the First World War. Nobody really knew about his work because so little was made. He designed strikingly modern pieces – vividly coloured, lacquered furniture – that were later copied by French Art-Deco designers like André Groult. I have a dressing room of his that is all yellow lacquer from 1912; a bedroom from 1910 that is lacquered in green, pastel green, a slightly darker green and silver. It is unbelievable. Another salon is upholstered in dark blue and painted in bright blue and the table in a light grey/blue. The other room was done after the War for an industrialist from Dresden. He made a whole room of total luxury.

This is your house?

Yes, one of my houses. I never go there, of course – I don’t have any time. I like to decorate, but I don’t have time for anything. I sit in my atelier, where I draw and live and sleep. For guests I do have another building, because I want to be left alone.

So there are many other houses you don’t live in?

I like to furnish houses. I am going to design the main floor of the Hôtel de Crillon here in Paris, and I’ll do a huge hotel in Macau. I cannot build houses myself, as I don’t know what to do with them. When you construct a house, you have to live in it. It doesn’t make any sense when no one goes there.

Is there a list of all these houses? Picasso once said that one must never keep a house. You close the door and you go on to the next, and the next…

The house with the Bruno Paul work is now completed. But I haven’t had any time in the last six months to arrange the books there; they are all mixed up. The libraries are in an adjoining building there. But the books stress me out.

Did Bruno Paul continue working after the War?

Yes. That’s why his career is so fascinating: he continued designing great buildings right up until the 1950s and 1960s.

Was most of the Simplicissimus archive lost and not documented because it was destroyed?

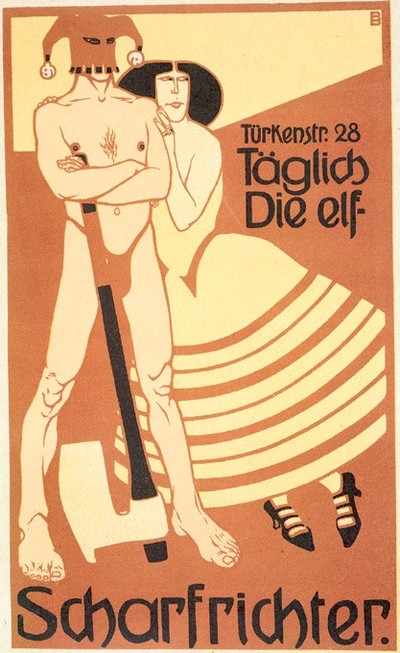

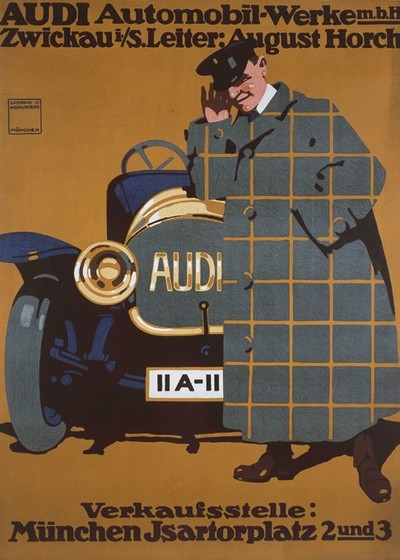

I have a few drawings from Simplicissimus – a part of my collection that I found in the attic as a child and some which I bought later on. The other great name from this era is Ludwig Hohlwein. Hohlwein is one of the artists whose fantastic early poster work I have in my collection. The advertisements that really interest me are from 1905 to about 1915 or 1920. After that there was an influence from the posters the French were making. They didn’t have the normal Kaiser-style advertising. For me they have something that is really akin to pop art. And it’s becoming rarer and rarer to find them. I started this collection more than 30 years ago with two posters that I bought for 2,000 francs at the time. Now they cost more than 200,000 or even maybe 400,000 euros.

Simplicissimus is unbelievably graphic, and it astounds me how it still looks so extremely modern. What is it about this pre-First World War era that fascinates you?

Well the first thing is that this was an era that I didn’t know. Also, at that time each caricature was an artistically perfect illustration — which nowadays isn’t always the case. They were truly graphic artists, who had a certain esprit, who found Wilhelm II and the whole imperialism of this period to be dreadful. And that’s the esprit of Simplicissimus.

A couple weeks ago, I read Harry Graf Kessler’s diaries, and it’s also interesting to look at his recollections of this period just before the First World War. It was an incredible time. On one side, it was extremely sophisticated, but at the same time what one sees in Harry Graf Kessler’s notes that in the months before the war it was horrible. He is a unique author.

I have been a huge fan of Harry Kessler since my early youth because of my mother. Even the way I dress is in a way inspired by him. The eight volumes of his diaries are always near my bedside in my houses. Kessler represents for me, Germany at its best – a Germany now gone forever. This year, there’s an auction in Hamburg where you can see his final estate, his mother’s things, his father’s patent of nobility, his death mask… But I don’t collect these types of things; I just collect books and a bit of photography maybe.

‘I have been a huge fan of Harry Graf Kessler since my early youth because of my mother. Even the way I dress is in a way inspired by him.’

It’s interesting because around that pre-First World War time, although there wasn’t really a movement like Bauhaus or Dada, what was happening still managed to keep similar-minded cultural people together.

I find this whole era fascinating: from Simplicissimus to Werkbund, and the German posters by Heine and Hohlwein. I think this is an unknown era to the larger public and yet there is something to really discover that is substantial and very strong artistically.

Exactly. It’s important not to forget this time. And by you speaking about it, it brings it into our consciousness.

Yes. That’s what I hope.

You have a huge book collection. When did your passion for books start?

It has been there my entire life. I was not interested in anything else but books, books, books and drawing paper. One time I told my father that I’d run out of drawing paper. He told me that I should use the other side of the paper. And I told him that I’d sworn to myself to never ever draw on the back of a piece of paper. Even today, the presents I appreciate the most are crayons, pencils, paints, paper and books.

Has the digital age changed your work?

No. Everyone around me is doing that, of course. I myself do not deal with the internet. Everything that exists on the internet about me isn’t actually done by me. That is done by strangers.

Everything is on paper?

Yes, although I obviously look around online a bit. But nothing there is actually done by me.

Is drawing a daily practice? You draw every day.

You know, for me drawing is the same as speaking and writing. I never understood that no one thinks the same way.

How is your day structured? Andrei Tarkovsky once said that we no longer have enough rituals in our lives.

Yes, but in my life this is a question of commitment or duty – Verpflichtung. I am always in a bad mood with myself, not with others. I’m never satisfied with myself. I’m always pushing myself. And normally, I do everything by myself. I do not have a studio with assistants who draw. If something is not done by me, I’m not interested. I do not want to try on clothes created by someone else. I am not a stylist, I am not a coordinator, that bores me.

‘I do not have a studio with assistants who draw. If something is not done by me, I’m not interested. I don’t want to try on clothes by someone else.’

Coming back to your drawings. Are there drawings that were done for a certain purpose?

I myself do not have any drawings. I do not store them. They are sent to the companies or newspapers; I draw caricatures for the Frankfurter [Allgemeine Zeitung]. I work for the rubbish bin. If someone wants a drawing, I have to do it. I love the process of drawing and making, but I am not interested in keeping something I’ve done.

Is the idea of having an archive and a catalogue raisonné non-existent?

It’s all done by others. I do not want to deal with that. I need to know what I have done the day before yesterday. It automatically keeps on going on. That is my job. My job is not to dwell on my past in complacency.

That is why I thought it might be interesting not to talk about the past but to talk about the future.

I do not have a past. Ich erinnere mich daran nicht. I don’t remember.

Let’s talk about the now then.

Yes! The now is perfect, that is what I want. I am lucky to be able to do what I exactly want, under conditions that are really great. As my mother said, ‘You may have done something else better. But as you are content with what you are doing now, it doesn’t matter anymore.’

It is March 2014. What are you working on today? What are the different things you’re working on?

This morning at work?

Yes.

This morning, I had to read all the press clippings from the runway shows, I had to answer all the phone calls, and I had to organise the next projects. The day was gone in three seconds. I actually had to do a costume for the tombola girls at the Bal de la Rose in Monte Carlo, where we wanted to do something constructivist, but I did not have any time for that. I also had to do a caricature for the Frankfurter. They’ll get it on Monday, it wasn’t possible today.

A lot of our friends from architecture are known through their unrealised projects; they are constantly publishing their unrealised projects until they get built. Do you have unrealised visions and utopias?

No, my job is much more simple. It is easier to make a collection or décor than to construct a building. I wanted to build a house with Tadao Ando, but in three different locations, we didn’t get permission to build. I still regret this. As for Zaha [Hadid], it is much harder to live in her houses. It is great what she is doing, the villa is great – the one she did just outside Moscow – but I am not so sure about living in it. Here in Paris you can only do chalets or roofs à la Mansart.

Are there other unrealised projects?

I have so much to do that all my projects are related to my work. I am not unhappy though. I don’t think of myself as an artist, and I never have. I’d rather think of myself as someone who does what he needs to do, does what is expected of him, and concentrates on the world he engages in. I mean, a day has only 24 hours; there’s only so much one can do.

Last time you told me about a chocolate construction; you wanted to make architecture from chocolate.

Yes, this has now been successfully realised. In general, everything I plan is realised. But maybe that’s just because I am not very ambitious.

You definitely are! But there must be projects that have been too big to be realised?

No. Nein, das war immer möglich. Everything was possible. Anything that people have suggested to do, has been done – otherwise I would stop. I am not fighting windmills. I am not Don Quixote.

[Laughs] Going back to books, have you ever had the idea to build a library?

No. I never said, ‘I want to have a huge library’. I found a lot of books, I bought them and read them. I wanted to have them. In the end, there was an enormous amount of books – about 200,000 to 300,000 books.

Do you have them classified?

No, not at all.

You were born in Hamburg. I was always obsessed with Aby Warburg’s library there.

Yes, me too! It’s great. The Warburg family were great people.

Did it play a role in your life?

No, when I was a child I hardly knew of it. I only lived in Hamburg for a short time. I spent my childhood in Bad Bramstedt which is near Hamburg in Schleswig-Holstein. I was only in Hamburg for about two years – at that age you can’t be that obsessed with anything. At that age I only had one idea: to get out of there. And my mother said: ‘Hamburg is supposed to be the gate to the world, but it is only the gate!’

But Aby Warburg’s library has not been a direct influence?

No, I learned about this later. I knew people, such as my grandfather, who had great libraries. He had 30,000 to 40,000 books — not quite as crazy as me.

‘Everything was possible. Anything suggested, has been done – otherwise I would stop. I’m not fighting windmills. I’m not Don Quixote.’

When we met two or three years ago, you told me not only about collecting books, but also actually making books.

Yes of course, as a publisher with Steidl. I am a paper freak. If you would ask me what I like the most, I would say, paper. I always have a notebook in front of me. I was born a paper freak.

How is it when you are travelling? Does your office always travel with you? How do you travel?

I mean, it is quite easy for me to travel, as I travel by private jet. I have a bookshelf and a suitcase with drawing materials. I do not fly the regular way. I only fly when I have to photograph or when I have to go somewhere for business. I don’t go on personal trips – only a month to the south of France in the summer. But otherwise I hate it. The era of travelling is out of date. With all the mass tourism and the telephones it is horrible nowadays. I cannot walk down the street without being photographed.

How do you work when you are travelling? Do you have notebooks?

I could work anywhere. I take myself with me everywhere, as my mother said.

Do you have a favourite city?

Probably New York. I always have the same suite in a the same hotel.

Where is this suite?

At The Mercer. In Milan, when I am there for the Fendi shows, I stay two to three days, and I usually stay at the Four Seasons, because I always have the same room there as well and the people know me. I also have a drawing table there, which is perfect.

You have worked independently for decades as you don’t work with only one company.

Sure, but I never wanted to work with only one company. Also the one that is called ‘Lagerfeld’ does not belong to me. I don’t want to be anyone’s boss. I don’t want to have any staff. I don’t want to have that responsibility. I find this kind of relationship superficial. I do not have an ego trip. I don’t care whether the brand that I’m working for is called Chanel or Fendi. What I do is the work, and the thing that matters is that I can do it under good conditions. ‘No’ does not exist. When someone says, ‘We have to let this go. We don’t have the resources.’ — that’s it. But this has never happened to me.

Everything is possible.

Sure. The Lagerfeld brand was wrong in the past, because they thought they could be competitors to Fendi and Chanel. Now they understand what I always wanted, that they have to have a different price point and that they have a totally different esprit. This is good for me because we are living in 2014 and no longer have the mundane lives that people had in the 1950s.

The curator Harald Szeeman said that his work as a curator at one museum was the most sustainable way of working. You’ve been working for Fendi and Chanel for decades already.

For Chanel it’s been 32 years, and for Fendi, 49.

How did you make it work?

I am a nice person and easy to work with. I understand the problems of the people I work with, and I don’t have ego problems or take myself too seriously. I take the work seriously, but that’s it.

Do you have lifetime contracts?

Yes. Not from the start, it happened along the way.

That is interesting, as it is really rare.

There is no other case that is alike.

Do you see yourself as an artist?

I am not an artist, I am an applied artist.

Do those differences still exist?

Applied art is something like craftsmanship. There are great pieces. But nowadays everyone wants to be an artist. In the past, designers and couturiers wanted to be mundane. That is not à la mode anymore. Now, everyone wants to be an artist. Recently a very famous designer told me, ‘In my world, the world of art…’ And I said, ‘Why, did you stop making clothes?’ And she is still making clothes. And another designer told me she’d make clothes for intelligent women only. Today she is broke.

The brand does not exist anymore?

No.

Talking about applied arts…

Isn’t it a good name? There are great people such as Henry van de Velde.

I wanted to mention him as well! Van de Velde is also one of my great heroes. Could you talk a little bit more about the applied arts from the past that have inspired you?

Yes, the Wiener Werkstätte [Viennese Workshop] influenced France even when the people didn’t know where it came from. Bruno Paul also saw that in Vienna and copied it for his brand that was doing interior design. Wiener Werkstätte and Deutscher Werkbund, all of this is great. And [Charles Rennie] Mackintosh and the whole Glasgow School.

How do you see Charles Rennie Mackintosh? And his work? Is that important to you?

Very. He had a huge influence, because he influenced the Vienna Secession. He really founded something that wasn’t there before. It is wonderful.

Your work covers all dimensions of life. Is the Gesamtkunstwerk important?

It’s more that each part complements the other. I don’t see it as a whole. I’m not that serious – you overestimate me. When I do something I’m not doing it in relation to other things. I hold onto this idea of Gesamtkunstwerk. I do not think like that at all. I’m like a lansquenet or a soldier on a battlefield. I just start working. Once the field marshal or the king is out of sorts, I run over to the enemy’s side. That is how it was back in the day — essentially I am a lansquenet.

How did you come to photography? What was the epiphany when you started to do photography in the 1980s?

I can explain very clearly. At Chanel, we do this dossier de presse – have you ever seen it?

‘Recently a famous designer told me, “In my world, the world of art…” And I replied, “Why, did you stop making clothes?” And she still makes clothes.’

Yes, sure.

When I came to Chanel, they were done by a photographer. You do the dossiers de presse when the collection is not yet ready, but you have to know everything already. For the 1987 collections, the photographers were bad. Eric Pfrunder the image director shot the collection three times with different photographers, and it still was not very good. Then he told me, if it is that complicated, we should do it ourselves. I got an assistant and a camera and did them myself. And then it developed from there: editorials, advertisements and even museums. I didn’t ask to go into this field.

And it developed also into books.

Yes, all that somehow evolved, without saying that I wanted it. I only did what someone suggested, I have enough to do for myself.

You do fashion photography of course, but there are also landscapes and travel photography.

I love architectural photography and landscape because you can do it by yourself and with old cameras. For the advertisements – look how many people I have here — I have a permanent staff of six people for these things. It’s a completely different discipline.

And how many people work here overall in each area?

You have to understand something: nobody works for me. They are always paid by someone else. Nobody is dependent on me. Apart from the staff in my house, no one.

This is quite unique.

Yes, but I need to be free. I want to break free – like the song by Freddie Mercury.

What kind of music do you listen to? Dan Graham said once that one could actually understand an artist only when one knows what kind of music he listens to.

I am very much interested in what is new right now. I mean, listen to the music at our défilés. I choose it with Michel Gaubert. I am interested in what is happening today, but I also have a great knowledge of classical music from all periods. I am fanatic of Strauss. I knew the text of Der Rosenkavalier by heart when I was a child, as I love Hofmannsthal.

It is interesting that you say that the past is not of interest for you.

No, the past is interesting, but you can take elements from it to make a better future. That’s what Goethe said, not me.

And Erwin Panofsky said you can take fragments to build the future.

Exactly, it’s the same sentiment, only put in two different ways.

You did something which happens a lot right now – revived a fashion brand.

When I started working at Chanel about 30 years ago, people told me not to touch it, it’s dead, and it won’t come back. But that’s actually the main reason why I accepted — there is nothing better than a challenge.

‘Yes, the past is interesting, but you can take elements from it to make a better future. But that’s what Goethe said, not me.’

It was a taboo?

Yes, sure. But I made a global business out of this taboo. This is what everyone does. After me, there was Tom Ford and John Galliano, and now it is everywhere. I like that, because the brand gives you a guarantee – there is capital behind it. It is not easy for young designers to build something up by themselves worrying day and night. And what I also do not understand are the people who have major contracts and then resign, as it is too much for them. I am sorry, this business is for Olympic athletes. If this is too hard, then they should do something else. If they drink too much or take too many drugs, fine. But then they should have a small home business and then manage the financial problems and how to survive – then they wouldn’t have enough time to drink.

Do you only drink coke?

Coca Light.

That is the only thing you drink?

Yes, I never drink alcohol. I do not eat sugar or meat either.

And what about coffee?

That is too much. I have to decide between coke and coffee.

Balzac drank 50 coffees a day.

Yes, and he died a little bit earlier then I will. He was only about 50 years old.

What are you reading right now?

Right now I am reading about Edmund White’s time in Paris, [Inside a Pearl. My Years in Paris]. I’m reading it because there are so many mistakes in it. And I am also reading the biography of Clarice Lispector, do you know her? Have you read about her?

Yes, I know her work.

Do you know who she was? She was the Brazilian Virginia Woolf. She died about 50 years ago. She is of the same importance in Brazil as Jorge Luis Borges is in Argentina. I also love Borges, his poems, it’s all great. My paradise is a library. Heinrich Mann once said, ‘A room without books is like a house without windows.’

Very nice. Do you also write poems?

No, I am only good at writing prefaces, which I’ve done a lot.

What kind of prefaces do you write?

You have to ask Gerhard Steidl. He has hundreds of prefaces I have written.

We should make a list and publish it.

Yes sure, he even wanted to make a book out of it. I am quite good at writing – even more so in English. It’s better than in German or French, but it doesn’t matter to me.

You still work in so many parallel realities: photography, books, brands, Chanel, Fendi…

One inspires the other. It is a mutual stimulation.

What is energy? You once said that it is like a desire, it is different things. How would you define energy, as your energy is unbelievable?

My curiosity is just like antennas on roofs, you know? I want to know everything, I read all the newspapers – I want to keep up to date.

This was the same for the Renaissance scholar, Athanasius Kircher, who in the 17th century imagined that he could have all the world’s knowledge all in one place — in his head, in one person.

At that time, it was much harder to gain more knowledge. Nowadays it is not that hard anymore.

Exactly. But today there is much more information.

Yes, there’s more information, but people are more superficial; they know about less things. They put too much trust into machines and think that they do not have to remember anything – it was different in the past, especially in the 17th century. So much has happened since then in 300 years. Their minds were not that overloaded as ours are nowadays. Everything was much clearer and simpler. There is this book called Das Inventar des Intims, in which there were the inventories of wealthy people who had died – their books and furniture. They had relatively few books. Even Mademoiselle de Lespinasse only owned 80 books.

‘In the book Das Inventar des Intims, it lists the inventories of wealthy 18th-century people. Even Mademoiselle de Lespinasse only owned 80 books.’

That is scary! I have 30,000, and you have 300,000. What will you do with them all?

Who knows? Who cares? The Devil may care! All that starts with me and ends with me. I really don’t care. I don’t have a teaching side…

This is what I wanted to ask you: you do not teach, but you do have an inspirational role at the same time.

I actually did in Vienna, at the University of Applied Arts. That’s when I realised that I am not especially interested in school or the students.

Do you have a favourite book?

A few. It depends on the language. My favourite French book is of the six poems by Catherine Pozzi, which I published in a trilingual edition.

How many different collections do you have?

I do not really know. You know, in one of my houses I have a whole floor where all of my posters are hung up, because they have to be framed since they are so fragile.

Do you have an art collection? Do you like to collect art?

Yes, but I’ve given everything away. I didn’t have enough space because of my books.

So the books took over!

Yes, because you can keep art in your mind.

One question I’d like to ask: I am running a project on Instagram. Umberto Eco said that handwriting is disappearing in the 21st century.

That’s not the case for me! That is why I love using a fax all the time, every day. With all the buttons, I feel like a bad secretary! Do you know what is most irritating? It’s when a computer auto-corrects! You can’t play with words anymore. It makes me hysterical.

It can be from you or a message to the world.

[Karl writes the sentence:] ‘Ein Zimmer ohne Bücher ist wie ein Haus ohne Fenster.’ That’s Heinrich Mann. ‘A room without books is like a house without windows.’ I sit in front of a glass window, and I cannot destroy it to get there were I want to. I see it, but I am never satisfied with the outcome. It is a strange feeling… but quite healthy, I think.

It is always a new beginning.

Do you know what the beginning of the end is? Complacency.