Alasdair McLellan returns to Doncaster, South Yorkshire to discuss how the landscape of his youth continues to inform his aesthetic.

By Jo-Ann Furniss

Photographs by Alasdair McLellan

Alasdair McLellan returns to Doncaster, South Yorkshire to discuss how the landscape of his youth continues to inform his aesthetic.

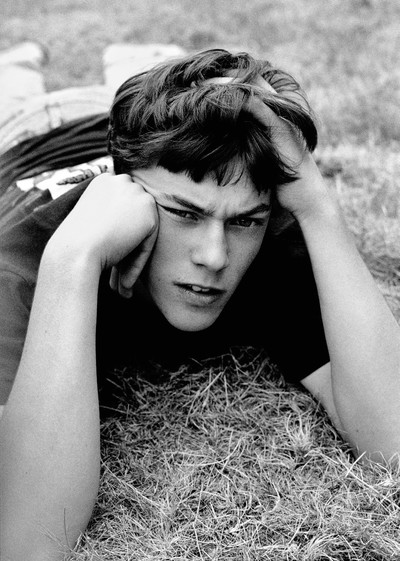

Alasdair McLellan started his life as a photographer in 1987, aged 13. In the first picture he ever took, a young boy looks out, a similar age to the photographer, wearing a green nylon parka edged in brown, synthetic fur – the kind always worn at school then. He is disappearing in tall grass; a lush green field fills the picture plane bathed in spring light. This picture was taken in Tickhill, Doncaster, Alasdair McLellan’s hometown. It is a place on the borders of South Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire; rural yet industrial, close to the many pit villages that dot the area in this coal mining heartland, where many of the actual pits have now closed.

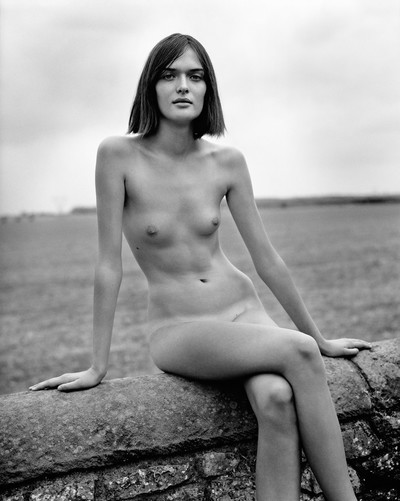

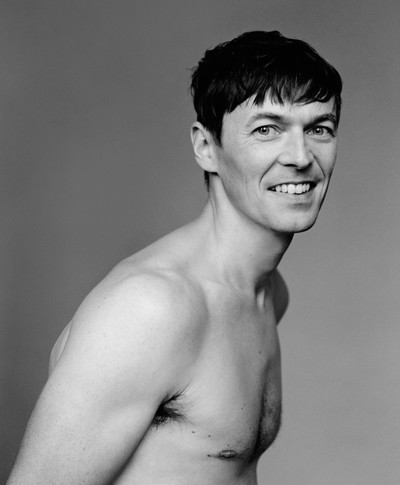

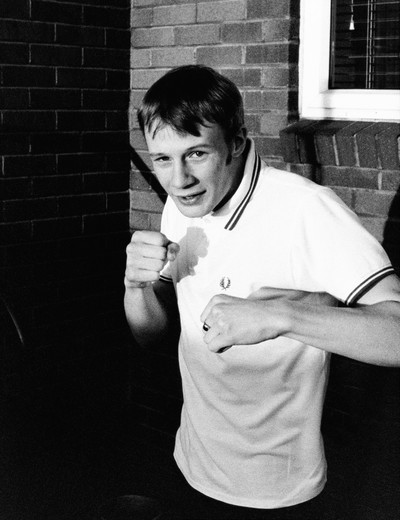

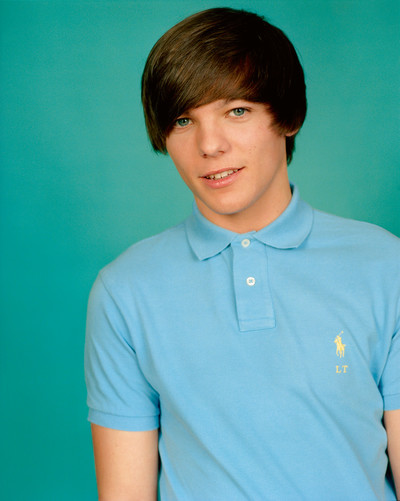

His pictures today have changed little; his way of looking at the world is almost exactly the same, particularly his way of looking at the world through a photograph. The people might have grown up, but they are still the same people, both in the picture and the one taking it. In other ways, outside the photograph, their worlds have changed irrevocably. Regardless, in Alasdair’s photographs their 13-year-old selves still show in something untouched about them and there is always springtime light. Almost ten years later in 1996, Alasdair first started taking pictures for magazines, and I had just started working on them; we have worked together ever since. His pictures then, now and in the ten years previous featured his friends from Doncaster and the environments they were all part of. This is particularly true of his best friend, Jamie Atkinson – they met at school when they were both 14 – and his new friend, the model Sam Rollinson – he first met Sam two years ago when he booked her for a shoot, intrigued by the fact that she too was from Doncaster. They are now jokingly referred to as his Doncaster muses. It should also be noted that One Direction’s Louis Tomlinson is also from Doncaster and makes a guest appearance here.

‘All we did was walk to the big park from the little park or go to the chippy. Then sit on that bench. That’s all you did!’

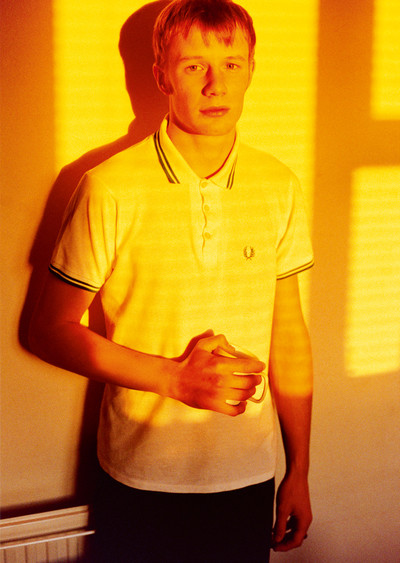

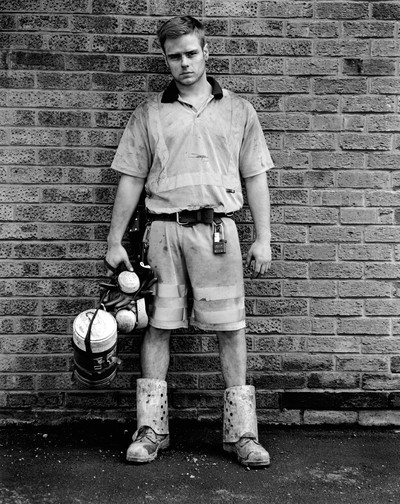

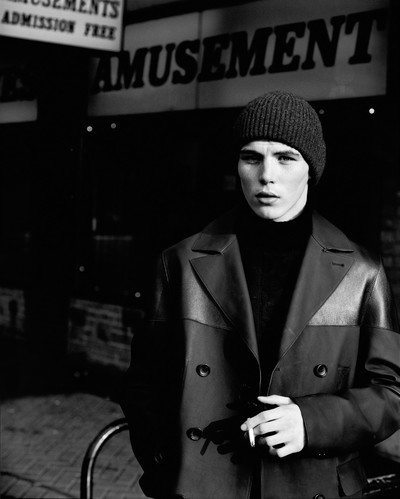

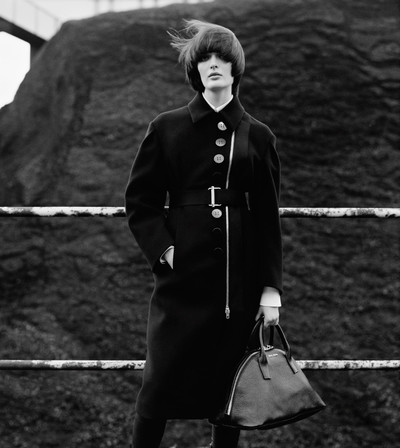

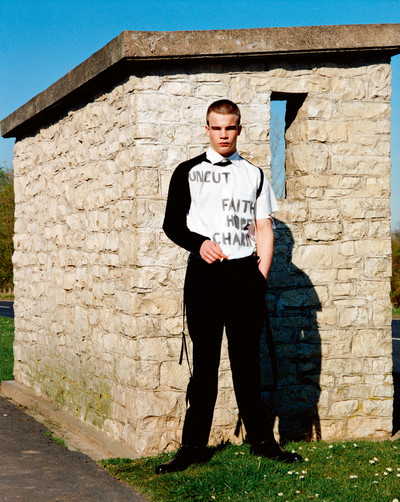

Being from the North of England, Alasdair grew up on a constant diet of kitchen-sink drama through films, television and pop music, and it is these things that infuse his pictures as much as the ‘real life’ subject matter. Alasdair has always had romantic notions about being English and Northern and wanted to show it. Yet his photography is often in thrall to the American rites of passage film as much as to his own actual rites of passage – something as innocuous as a bench that everyone gathered around as kids in Tickhill is invested with as much meaning as the Ferrari in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. People sitting on benches often reoccur as a motif in his pictures, although more recently that person might actually be Claudia Schiffer. Yet it is perhaps the pop video, the record cover and the song lyric that holds greatest sway in his imagery. The clothes in his fashion shoots often function as a wardrobe to re-enact significant moments, visual memories or feelings from songs – or all three in some cases. Sam Rollinson standing outside a South Yorkshire colliery in a Miu Miu coatdress for Vogue, is an oblique nod to Viv Nicholson standing on a slag heap in a short crochet creation for the cover of The Smiths’ Barbarism Begins at Home. Alasdair does not believe in being too literal, takes a great interest in fashion and is very knowledgeable about clothes, at times taking off with a suitcase and styling his own shoots.

Alasdair McLellan has loved Bruce Weber’s photography since discovering his work as a teenager. The romance, the feeling and playful sexual charge that infuses each of Weber’s pictures has set an example for his own. Yet he was led to Bruce Weber’s photography by the Pet Shop Boys’ Being Boring video, directed by Weber for the song’s release in 1990, and he is a great admirer of the Pet Shop Boys and their unashamed pop sensibility. Yet, very tellingly, he once declared: ‘Bruce Weber art directed a country. Nobody else has done that.’ It became clear Alasdair wanted to do that too, and he wanted to do that primarily through an idea of a certain type of working class English boy and girl – very different from the people Bruce Weber has mythologised. The country this time would be the North of England, the landscapes around Doncaster and South Yorkshire that he grew up in. His other great hero of ‘art direction’ and fellow mythologist of the North is Steven Patrick Morrissey. His unfaltering observation, both in his eye for The Smiths covers and in his ear for The Smiths lyrics, is the thing that, as a budding photographer, Alasdair most admired and took on board. And when he is dismissing something of no relevance, interest or merit today, he will often declare: ‘It says nothing to me about my life.’ Yet something lyrical, melancholy, mythological and unashamedly pop always does, and characterises his pictures in a way that makes it clear they are also for mass consumption.

Bradford’s Buttershaw Estate had a pull for the photographer at the beginning of his career taking pictures for magazines. It had been immortalised in Alan Clarke’s film Rita, Sue and Bob Too, a film that he has always loved. It was released in 1987 and was written by Andrea Dunbar, a young woman who lived on the estate who died a few years later. Although they have their extreme differences – Alasdair’s life growing up was a lot nicer, more rural and more lyrical than Andrea Dunbar’s – without realising it, they have their similarities. If Morrissey, self-consciously, has Shelagh Delaney, Alasdair McLellan, not so self-consciously, has Andrea Dunbar. There is always a sense of a real experience, a real sense of place and a real life in his pictures, just as there is in Andrea Dunbar’s writing. Although Alasdair McLellan now has frequent copyists, his approach to and reverence for a certain type of boy or girl or a way of dressing now appearing commonplace, it once wasn’t. Despite this proliferation of his style, the images produced never have quite the same charge of reality, experience and truth mixed with fantasy that Alasdair McLellan’s photographs do. Here, they have something to say about his life.

Jo-Ann Furniss: I never quite realised before going to Doncaster with you and seeing Tickhill, Edlington – where you went to school – Harworth and all the other places where you grew up, how dominated they are by mining. Or were dominated by it…

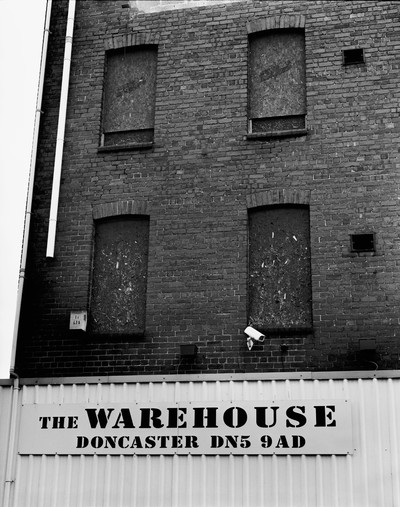

Alasdair McLellan: Tickhill is a very nice village, and it is more rural. But going to secondary school in Edlington, that was a real pit village where the Yorkshire Main Colliery was. I went to that school in 1986, and they had closed the mine in 1985, so it had a very big impact. I was meeting people at school for the first time, and nobody in their family had jobs. It was such a big contrast. But Doncaster town centre, it has always been similar, a bit of a mess. I was not really around when it wasn’t; the industry had already gone.

Do you think you made a conscious effort to ignore the grimness around you? Or are the industrial strife and post-industrial landscape part of the romance in your pictures? There is this longing in them for something lost…

I think there is. Well, yes and no. It’s not fun to live it, but there is the incredible aesthetic of the lost mines and in the ones that are working. A lot of my friends were from mining families and there was romance in that, the generations who had all done similar things.

‘Carina White thought she was Madonna. She’d wear a leather jacket, baggy jeans, a Breton T-shirt. It was naff as fuck, but it looked quite good.’

What did your parents do?

My mum worked for Yorkshire Bank, and my dad worked for a company that sold number plates. Tickhill was quite wealthy because it was full of farmers who did quite well. One of my friends lived down the road in this place called Stud Farm, and there was a huge amount of agriculture in the area. There is something much more pretty, aesthetically speaking, in that. There is something quite beautiful about Conisbrough, and the light is always lovely where I am from, that always helped. Rain would clear quite quickly, so it never really felt gloomy or depressing. That had a big impact on my pictures and is still an influence; I always try and go back to that light and colour.

There is something very cinematic in your pictures, and the light and colour is quite cinematic as well; did that come from the landscape? Why were you drawn to take pictures of it all?

I just grew up around it, and I like to go back to that. I got a camera when I was 13 – even though I was really into music – but they did sort of come together because I was always looking at record sleeves. Listening to music and staring at the sleeves was a way of escaping. I worked from a very young age – I was a DJ; we had a mobile disco – and Stock, Aitken Waterman obsessed my mate from the farm, who I DJ’d with. He watched The Hitman and Her and wanted to be Pete Waterman basically. Whereas I looked at album sleeves, very few magazines – there weren’t many available where I lived – and music videos. I didn’t know what it was, but I wanted to be part of that – although I didn’t know quite what ‘that’ was!

So you wanted to do the visual accompaniment to a sound more than anything?

Basically, yes. I have always really liked music, and I particularly liked Morrissey because his lyrics were very visual and romantic and from a similar place.

And you were very inspired by The Smiths’ sleeves as well…

But it wasn’t just those that inspired me. I really liked Herb Ritts’ sleeves that he did for Madonna – my music taste has always been pretty broad, I like people if they are good. There is also something to be said for a Bros sleeve; I liked their hair and their Avirex jackets. I don’t particularly like their music – although I am quite fond of I Owe You Nothing and I don’t mind Cat Among The Pigeons. My mate Mark Smith, who was obsessed by Stock Aitken Waterman would always make me go to The Hitman Roadshow when it was in the area – and he wasn’t even gay – he then went on to work with Jive Bunny. My other mate, Lloyd Roper, who DJ’d with us, liked house music. I was somewhere in between. I just used to complain that my mate was always talking over records trying to be Pete Waterman and ruining songs. So I DJ’d in pubs, in town, at working men’s clubs, at weddings… I worked and listened to music all of the time and I was only about 15 or 16. I shouldn’t have even been in those places. But we were quite good. We were all the same age and in the same year at school.

And this was really your entry point into being a fashion photographer…

Well, there was good stuff in the charts then, and I could look at all sorts of things and be inspired. I’d look at a Bobby Brown sleeve and think, ‘I like his haircut!’ I was never really consciously into fashion, but I learnt the clothes would make the difference, and I could control that aspect. I learnt that later on really, that you could do anything in fashion, make any image, as long as you put the clothes in it.

And friends would pose for you…

There was always Jamie who just is very natural in front of a camera. And I had a friend called Liz Jackson who was basically posing all the time. She had a haircut a bit like Madonna’s at that point and would always want to do something. So we’d recreate these sleeves.

Was she the girl you told me about who would walk through Tickhill thinking she was Madonna carrying a stereo playing the album on a tape?

That was Carina White. She thought she was Madonna, and this was around 1987 when I was 13, so circa True Blue, the album had come out in 1986. She would walk through the village wearing a leather jacket, baggy jeans, low heels, a Breton T-shirt – looking literally like Madonna did in the video – with the music playing on a shit stereo. And then she’d throw her jacket over her shoulder – just like Madonna – and storm off out of the park. I remember thinking that’s naff as fuck, but it does look quite good.

‘Why wouldn’t somebody be sat on a bench wearing Prada? We did that shoot with Claudia Schiffer the way we would have at 13!’

Did she sit on the bench in the village?

She did sit on the bench with her stereo. We all sat on that bench. All we did was walk to the big park from the little park and see who was around, maybe go to the millpond, or the chippy where the older kids were, then sit on that bench. Or meet at the bench. That’s all you did! Or go to the other bench. Ha!

And that’s why you always have benches in your pictures?

Yes, because of the bench. And I just think well, why wouldn’t somebody be sat on a bench in Prada?

I remember seeing Claudia Schiffer sat on a bench in one of your pictures for Vogue Paris. And the first L’Uomo Vogue shoot you ever did – with Joe McKenna – which was a very big deal for you then, and you insisted on going back to Tickhill to shoot it. I think you also involved the bench in that shoot too… You always used to go on about that bloody bench!

Yes, we literally did that shoot the way we would have walked around when I was 13 – only with Joe McKenna!

When you first started shooting for magazines you were very influenced by the director Alan Clarke, weren’t you?

Well, quite a few directors, but I was interested in him because I knew where it came from. It is really what turns you on visually and it all looked quite good.

There is also always a sense of narrative in your pictures, not some heavy plot, but a story is always alluded to. That’s why film has always seemed like a big influence on you as well…

I always feel that you have to put yourself in the photograph a little bit – that this is so important. There has to be a story and is partly your story. I like to get inspired by memory or a certain feeling, otherwise you are just recording fashion, and that’s great if you have an amazing stylist, but it is not always going to be like that. And I don’t always want to just record fashion anyway, I want to do more – that is why so much is drawn from where I grew up. Or from a Bobby Brown video. Or a Pet Shop Boys video. Or from Papa Don’t Preach. It was all part of growing up really, and there are emotions in all of it.

Do you actually see yourself as a fashion photographer?

I do, and I don’t. I was only really exposed to magazines like The Face and i-D around 1989 or 1990, and it was really then I became interested in fashion. I remember Ian Brown being on the cover of The Face and thinking how good he looked. And then seeing Corinne Day and David Sims shoots, those being great and thinking that what they were doing fitted in with how I had been thinking. That me taking pictures of my friends – who I thought looked really good – was something that you could actually do in fashion photography. That what Corrine Day and David Sims were doing made it achievable for me; that those kinds of pictures actually existed in magazines.

At the same time that you liked reality in images, you didn’t reject an idea of fantasy either. Growing up in the 1980s gave you a taste for both. I think that peer group who grew up in the 1970s were much more influenced by the aesthetics attached to that decade. Whereas our peer group were very much children of the 1980s…

A lot of the films I really liked and like are from the 1980s. I like all of those American rites of passage films, those brilliant John Hughes films. I have always found those films very emotional – they might be fake emotions, but I don’t care, I still find them emotional! And the music tracks were usually British artists; the way music was used by John Hughes was just really good. Even though I don’t like Pretty in Pink particularly, there is a good scene where Ducky is listening to Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want. And the way he used The Dream Academy version in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off as well, in the art gallery scene, it was just very emotional. I think that kind of narrative has played a big part in my photography as well. I even found 90210 emotional at times.

I think our peer group has always liked the idea of America as well…

I just thought it felt so glamorous and that the American teenage experience was so intense.

It has very defined rituals that are very appealing aesthetically. Whereas our rituals are a bit more about getting drunk in a park and a bit rubbish, theirs appear formalised and glamorous. And I suppose that’s where Bruce Weber comes in too. When did you first become aware of Bruce?

It was actually Herb Ritts that I first really became aware of, mostly through the work he did with Madonna. And then probably the biggest impact that was made was Bruce Weber’s Being Boring video for the Pet Shop Boys. I was aware of the Calvin and Ralph ads because I couldn’t help but notice them – although I was not always aware of who did them – but I really thought that video was quite something. I paid attention. I was 16. It made a big impact.

And when did you decide you wanted to apply what you felt about those images to an idea of England and the kids you grew up with here?

It came naturally; it was everything I related to basically. I had already been taking pictures of my friends for years. It is my emotional connection to people and places. It is why I do most of my landscapes in South Yorkshire still; you can feel the connection in the picture. I can take a picture on a similar housing estate in London or wherever, and it just does not feel the same. There is a difference in the feeling of the picture, and I just really don’t know why. Other people can tell the difference as well. That’s why to do this story it was important to go home; my pictures, that aesthetic, in the end it all relates to me growing up there.