Peter Philips, Creative and Image Director of Christian Dior Make-up, meets The Queen of Art-Gore, Cindy Sherman.

By Jerry Stafford

Photographs by Nikolas Koenig

Peter Philips, Creative and Image Director of Christian Dior Make-up, meets The Queen of Art-Gore, Cindy Sherman.

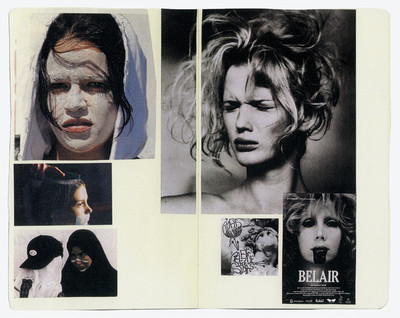

The eminent writer Simon Schama has described Cindy Sherman as ‘an anatomist of self-consciousness, a collector of living masks.’ The artist, whose work since the early 1970s has concentrated on ‘series’ of meticulously composed self-portraits using costumes and make-up to transform her identity – sometimes abstracting the image to such an extent that the human ‘subject’ is completely effaced – has possibly one of the most recognised names in the art world, but certainly the least recognised face.

Working in almost obsessive isolation, resolutely sourcing accessories, costumes, make-up and prosthetics for each new identity, the 60-year-old Sherman calls upon a wide range of cinematic, pictorial and personal influences to construct her frame, whether it be a rear-projected Tippi Hedren-like Hitchcock heroine, an illicit scene or gesture from a 1960s De Sica or Antonioni movie, Hans Bellmer’s sexually charged yet childlike deconstructed dolls, the kitsch, nightmarish scenarios of a Dario Argento giallo, the gore and grotesque of Jan Švankmajer’s stop-frame animated fairy tales or the lascivious grimace of Caravaggio’s Young Sick Bacchus. Along the way, Sherman’s little shop of horrors has become one of the most unsettling and unforgettable oeuvres of modern times, and the artist one of the most influential of the last half-century.

And it is an oeuvre which – on the surface at least – makes Belgian make-up maestro Peter Philips’ own relationship to beauty and transformation almost laughably conventional. The former fashion-design student at Antwerp’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts (alongside industry luminaries such as Dior couturier, Raf Simons, photographer, Willy Vanderperre and stylist, Olivier Rizzo) was named Creative and Image Director of Christian Dior Make-up in 2014, following a tenure as Chanel Make-up’s Global Creative Director between 2008 and 2013.

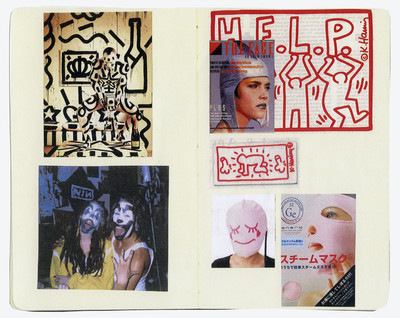

Philips’ reputation in the industry as an unparalleled cosmetic artist was initially forged in the late 1990s. His daring experiments with radical young creatives such as Raf Simons, for whom he infamously face painted a perfect-scale Mickey Mouse, landed him work with venerated photographers such as Irving Penn. At the helm of Chanel and now Dior, Philips has created not only many of the world’s most visionary beauty products but also the most coveted, with every season of sell-out cosmetics redefining how women across the world make their own daily transformations. Intrigued by the parallel and contradictory impulses between two artists whose careers, though disparate, have both been dedicated to cosmetic transformation, System invited Peter Philips to visit Cindy Sherman in her New York City studio.

Surrounded by carefully arranged shelves of vintage wax mannequin heads, torsos with glass eyes and exquisitely applied rouge and lipstick, boxes of platinum marcel-waved and beehived wigs, prosthetic breasts and other mysterious, unidentifiable protuberances, a conversation about their own respective methodologies and approaches to identity and aesthetics, to appearance and transformation, to the beautiful and the grotesque, begins to take shape.

‘While my girlfriends were turning themselves into ballerinas and princesses, I was more interested in turning into monsters or witches – ugly things.’

Peter Philips: So this is where you work?

Cindy Sherman: Yes, I’ve been here for the last seven, eight years.

Peter: It all looks so organised.

Cindy: Well, I’m not in the middle of producing any work right now; if I were then this place would be a real mess. I haven’t actually shot anything in four years. I’m just busy with paperwork and my archive.

Peter: So there’s a long period of time between each series?

Cindy: Sometimes, yes. But this is mostly because of the MoMA show I had two years ago: there was preparation for that show and the catalogue, then it travelled, and then another show in Europe opened right after that. So with all this going on, I’ve not actually been able to make any new work… You have to be careful what you wish for! You finally get to this level of success and you don’t have time to work anymore. I’m not like some artists who will go into the studio for six hours a day, every day, no matter what – 10 o’clock they are there, do whatever work they have to do and then they’re done. I find that with photography you have to plan ahead. I generally need a six-month chunk of time to commit to a project.

Peter: My father is a painter and he makes a living out of it – he has the most organised life. I wish I could be like that. He basically works office hours. I’m very chaotic but you have to have some sort of system in your head otherwise you get lost completely.

Cindy: So how did you get involved in make-up?

Peter: I never had the ambition to work in make-up. I studied fashion design at the Antwerp Academy, not really knowing that I wanted to be a fashion designer either, but I was intrigued by the whole myth of that school. When I was a kid I would see these very colourful-looking students walking around town, and I thought I wanted to be part of that. My stepfather had a catering business and the Belgian designer Ann Demeulemeester, and her team would always come in to buy sandwiches. So there I was, a young kid, and these ‘birds of paradise’ would come in with full make-up and hair. I just said to myself, ‘Ok, I want to be part of that.’

Cindy: Did the school live up to your expectations?

Peter: Well, while I was there I realised I really didn’t want to be a fashion designer. But I discovered all the aspects that are part of the big picture we call fashion, including fashion design itself and obviously make-up. So I kind of fell into this world because I have a good hand.

Cindy: The painterly side from your father, right?

Peter: Right. And Antwerp’s a small world, and so fellow students quickly found out I could do make-up. They’d start asking me to do the make-up for their shows because they had no budget. That is how I kind of rolled into it.

Cindy: But then actually creating new make-up products is a whole different thing.

Peter: That’s right. My main motivation for doing make-up was fashion and not really beauty; it was the theatrical thing of enhancing the work of a fashion designer or working on a photo shoot. When I started doing make-up in the 1990s, there wasn’t really a make-up scene as such. It was all about nude and grunge, minimalism and anti-fashion, and all that.

Cindy: Did that correspond to how you saw the world?

Peter: Well, my training was in nude make-up, so I found I could do really great skin tones. Then, step-by-step, I discovered lipstick and eyeliner and shading and sculpting. That is why my portfolio became 90 per cent of beautiful nudes, and next to that some really extreme make-up – conceptual painted faces and that kind of stuff. And I think people found that combination quite intriguing.

Cindy: When did you make the jump into creating make-up?

Peter: My first job as a make-up creator was with Chanel. They contacted me and introduced me to their studio. That’s when I discovered this whole new world of creating products, creating shades and creating textures. I am not a chemist, but at Chanel I then discovered this world of how to actually make what you’d normally just buy in a shop. With this, came the process of stepping away from doing niche editorial work for magazines and starting to really think about women and what they want – because ultimately, every woman wants to be fashionable, pretty and beautiful. So it was a great adventure, really fun. I also had a really good relationship with Karl Lagerfeld, so it was great to work with him in this link between beauty and fashion.

Cindy: And now Dior.

‘My main motivation for doing make-up was fashion not beauty; it was the theatrical thing of enhancing the work of a designer.’

Peter: After a while at Chanel, I found that I kind of missed that freelance world of shoots and shows. So about three years ago I stopped Chanel. And then I recently got invited by Dior, and I couldn’t really say no to this magnificent big fashion house! Plus, I am pretty good friends with Raf Simons who I’ve known for 20 years. It has only been several months, so it is quite new – but it feels like two years already.

Jerry Stafford: Cindy, where did your enthusiasm for disguise and transformation come from?

Cindy: From when I was a kid – maybe ten years old – because I had a suitcase of old clothes, old prom dresses and things like that, and I would play dress-up. Plus, I discovered some of my grandmother’s clothes somewhere in the basement – she had died years before, or maybe it was even my great-grandmother because they were really old clothes, from the turn of the century. I put them on, and I turned into this old woman. I have a photo somewhere. My girlfriend and I would turn into little old ladies, and we’d walk around our neighbourhood dressed like this. But then I discovered that while all my girlfriends were turning themselves into ballerinas and princesses, I was more interested in turning into monsters or witches – ugly things.

Peter: I used to play in the cellar at my grandmother’s place, but I would always dress up my brother and my cousins – never myself. I kind of choreographed and styled them. I think that basements and cellars kind of form people.

Cindy: Yes, because that’s where all the castaway clothes that nobody has worn in years are stored. I didn’t know I was going to do anything with this. I knew I was good at art school, but then I got so bored with just painting. I soon realised that once I’d learnt how to use a camera, it was much more interesting and quicker to come up with an idea and use the camera to capture it, rather than taking ages to paint.

Peter: I was surprised to learn that you do everything yourself, on your own. All the props… everything. Do you have to try everything out a few times?

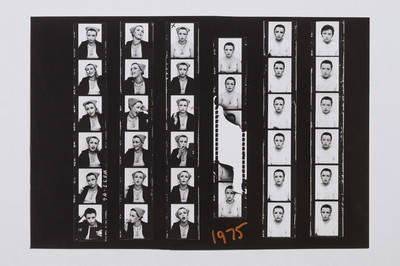

Cindy: Yes. But now that everything is digital it is so much easier for me. In the early days it was a several-day process. I’d shoot using contact-sheet Polaroids, so you couldn’t really tell the focus or colour. I’d shoot something, have to take off all my make-up, then take the films to the lab and wait for three hours. I’d come back with the contacts and then realise I had to re-shoot because it was out of focus or something. Sometimes it would be wrong, and after six or seven attempts I would just give up and move on to something else. Now that it’s all digital I can see right away on the computer if something’s working or not and make tweaks and changes.

Peter: Could you talk me through the process of where an initial idea comes from and how that gets physically transformed into a picture?

Cindy: To give you an idea of the process: for one of my last series – which were ‘society portraits’, they look like portraits of matronly women – I would think about the character based on maybe a dress or a wig or the combination of the two. I’d put the dress on and then maybe go through my wigs and see what worked. Once I felt that a character was starting to take shape in my head, I’d shoot the portraits in front of a green screen and then think about incorporating the backgrounds.

Jerry Stafford: Your own work, Peter, seems not such a solo process. You work in a very collaborative way, but is there anything that you work on completely by yourself? Do you research on your own?

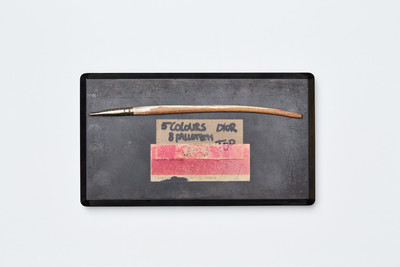

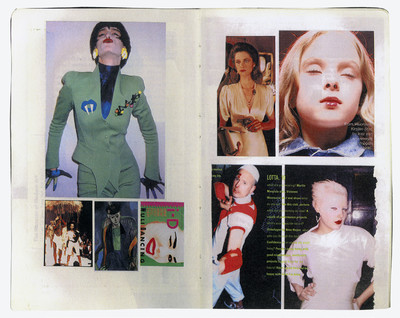

Peter: In August, when everyone else in Paris is on holiday, I do all the prep for the collections on my own – I am doing 2016 already. I am really in my own capsule, and my office is full of all these pieces of fabric. I never throw anything away make-up-wise; since I started, I kept everything because I can use them as a colour, texture or packaging reference.

Cindy: What are the considerations you have to take into account when you’re creating a make-up collection?

Peter: When I make a collection – there are four a year: spring, summer, autumn and Christmas – I have to make sure there are enough products that can please a woman or a girl no matter where she lives in the world: girls in Tokyo, women in Sweden, Brazil – all different cultures, different backgrounds, different beauty ideals and different ages. I would like them to find at least two products in a collection that they can use. It is like a puzzle almost, and of course all the while anticipating what might be a trend.

Cindy: What are the current trends?

Peter: Well, to be honest, we’re not living in an era of seasonal trends. There are so many different trends happening at any one time that fashion and beauty can no longer be dictated in the ways they were ten or 15 years ago.

Cindy: Does your make-up collection have to fit in with the clothing collection?

Peter: Not really, although I’m lucky to have the chance to create make-up products specifically for the show. For my first haute couture show for Dior, Raf didn’t want any big statement make-up; he wanted something that looked like nothing. The venue was mind-blowing, like a big spaceship with mirrored walls. There were holes in the wall every 15cm, and out of every hole was an eight-metre high living orchid, and the light was really intense. So I proposed what you call an applied eyeliner that was mirrored like the wall. I cut some shapes from this special paper; it didn’t look like anything special, but once it caught the light, it was amazing. The great thing is that because of my role now, I can actually put these into production – in the next few months they are going to be sold.

Cindy: So it’s not like an eyeliner pencil?

‘With a make-up collection, I have to make sure that there are enough products to please a woman or girl no matter where she lives in the world.’

Peter: No they’re glued on, application, like fake lashes. Not every show I can do something like that but this time I could. So that is a fun thing. The show was on the Monday, so we had the weekend to cut out our 62 pairs of ‘eyeliners in mirrors’ ready for the models.

Jerry Stafford: Cindy, what tends to come first in your work? Is it a material or a wig that influences the subject matter, or do you choose a subject and then look for components to bring it to life?

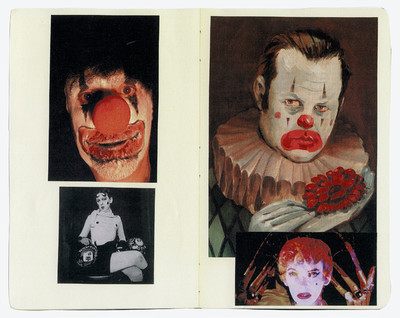

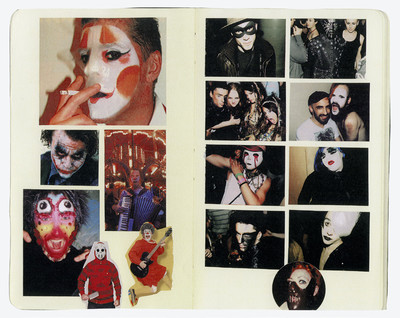

Cindy: It’s a combination of all that, because sometimes the whole theme for a series will be the first thing that really comes into mind, like the ‘clowns’ for example. Actually, that came to me as an idea based on something I had bought in a flea market; someone had attached big fluffy pom-poms to a really old pair of pyjamas to turn it into a clown costume. They’d even made a pointy hat that had a pom-pom matching the pyjamas. So I started thinking about clowns and then got the props. Sometimes though, it is like you say, just a wig that inspires a character.

Peter: Do you do research at flea markets?

Cindy: Yes, but I love going to flea markets anyway, so it’s half work half fun. With something like the ‘society portraits’, I did a lot of research online looking at old paintings and bad society pictures.

Peter: What was the starting point for that series?

Cindy: That series was inspired by a woman called Brenda Dickson, this kind of 1980s has-been soap opera star. I’d never heard of her, but she created this video that is on her website which is just the funniest thing in the world. It’s from around 1985: it starts out in this huge living room that is her apartment, just showing off how glamorous her life is; she comes out in this big shoulder-padded dress and some crazy hat saying, ‘Well hello, this is Brenda Dickson, if you wanna be like me then just watch this video tape and follow my make-up and style guide.’ She was so backwards with the make-up – you’d get such a kick out of watching it, Peter – she would say things like, ‘So, for blush you can do either orange or pink…’[Laughs] it was just hilarious… And in the background is this huge portrait of her; I was just astounded by the ego of the woman! That was when I decided I wanted to make these kind of portraits.

Jerry Stafford: Peter, you said you arrived at a time when make-up was all about stripping away to something pure and full of real emotions, while Cindy’s work is very much about layering and creating masks that express these sort of cracked and faulted characters.

Peter: I see Cindy’s use of make-up as a confrontation. In the ‘real world’, the things she explores are exactly those things that most people try to cover up – and that is the strength of it, from my point of view.

Cindy: I don’t know if you wear make-up yourself, but as a woman I do, for example, when I go out at night. So I have this whole other relationship with make-up that is completely different to how I use it professionally. Sometimes I want to put make-up on to make a character look like they are different from me, but as if they are not wearing make-up. And then there’s something like the clowns: that was really hard, because on one level I was learning about clown make-up, but then I was also trying to look like a different person underneath that clown make-up. It was a real challenge.

Peter: I love clowns, they’re so intriguing. They’re very scary, but at the same time they are like a magnet that draws you in. I love clown make-up too, because it is almost like Lucille Ball or Joan Crawford; if you look at those particular types of stars, it’s all about the big red mouth, the pale skin, the red hair.

Jerry Stafford: Do you see those bold colours still used much these days?

Peter: There is a lady who always sits alone in the Café de Flore in Paris who only ever wears full purple. She’s a real character, and when she was young she probably looked like Brigitte Bardot. But the first thing you think is, ‘Oh my God, that poor sad woman.’ And then you think, ‘Actually, wow, she is pretty incredible.’ She has full make-up – always lavender and purple shades – and I can totally imagine her apartment, like a boudoir full of feathers and things. I don’t know if she is sad or happy, but as long as she feels good and if she thinks she needs that, I think she can do whatever she wants. At least she is playing, maybe hiding something, maybe covering something up, maybe nostalgic for something, maybe she used to be very beautiful.

Cindy: Maybe she put her make-up on like that 40 years ago, and it’s just never changed.

Peter: Make-up is a very interesting and intriguing concept when you consider its range of uses can go from becoming a scary clown through to classic mise-en-beauté, as you say in France, which really means to make yourself pretty, to put forward your best face. It is a very complex issue in our society. But then you have other societies where make-up is tribal or for battles, or religious make-up… painting yourself and painting faces is a big, big universe.

Jerry Stafford: One thing I wanted to discuss is your relationship with the past. Cindy, your work refers to vast canons of cinematic references in the Untitled Film Stills and to modern and old masters, while Peter you work with Dior, a brand with a huge heritage. How do you both play with or subvert these past codes and genres to create something new?

Peter: It’s obviously interesting to work with a house with a DNA and with a heritage. I don’t want to just cling onto the past but it is interesting; I am discovering that Christian Dior himself loved to disguise himself and dress up. He loved to organise costume balls: there is this one costume where he had a big lion cape, and I think the headpiece was made for him by Pierre Cardin. There is a big tradition in Paris haute couture called the Catherinette: a yearly celebration for the 25-year-old girls who work in haute couture and who are still single.

Cindy: But that’s different from the debutante ball?

Peter: Yes, it is only for the embroiderers and seamstresses. They have to wear a hat that is made especially by them or for them in green and yellow – it’s an official thing and all the fashion houses still do it. There is a big ball at the end of the day and they have to go to the hôtel de ville, to meet the mayor. And there is always a fête déguisée – a fancy dress party. There are pictures of Christian Dior in his days of the Catherinettes which are amazing. If you do research into the heritage of a house, you bump into all kinds of interesting elements. Christian Dior was at the helm of his house for only ten years before he died. He started in 1947 and then died of a heart attack ten years later.

Cindy: Did someone take over right away?

Peter: Yes, it was Yves Saint Laurent for a few seasons.

Jerry Stafford: Cindy, in your Untitled Film Stills, you reference the 1950s, and obviously Dior is there because you are referencing the ‘New Look’. But how aware were you of fashion – as opposed to costume – when you were working in the early days?

Cindy: Early on, I don’t think I was that aware of it, other than knowing iconic Avedon photos of Dovima in Dior and things like that. I had heard of the ‘New Look’ from watching movies like Funny Face, but I didn’t know any history of, say, Dior or Chanel. Also back when I was working on that series – it was up until the 1990s – I think the general public didn’t know or care that much about labels. Things that we now take for granted like Prada or Gucci or Chanel or Dior being everywhere, it just wasn’t as present back then.

Peter: I think those brands represented a certain elite; today it is more democratic in a way.

Cindy: And copied.

‘You see something faraway, and it looks beautiful and very seductive; but as you go closer you realise it’s actually bugs crawling over a corpse.’

Jerry Stafford: Do you think cosmetics have democratised those labels in a way?

Cindy: Yes, I do.

Peter: People always say that about cosmetics: lipstick is the first step for any women to buy into a luxury brand. I don’t know if that democratises the luxury houses, but you can get a little foot in. Just going back to your question about old film references: When I was a kid I loved to watch black-and-white movies, which provided a really amazing lesson in light. Marlene Dietrich and Ava Gardener looked stunning, and it was all about the light more than the make-up. And when I look at your early work Cindy, I see how you shade and sculpt your face, and I think that is how you can make someone look very retro in a way; the way you shade and sculpt the face, by painting light or shadows…

Cindy: …directly onto the face.

Peter: Exactly. I see make-up in two stages: the black and white is like the under-dressing of the face – it is the basics, the negligée almost – it’s about the skin and the shading and lighting, the features and the way the face moves. Once you start moving or talking, it can change so much. And then I start dressing the face with colour. Then you can do anything: an era, a statement, gothic, punk, romantic, the accessorising of the face. That is why I love film. I learnt so much about light from those old movies.

Jerry Stafford: Cindy, you are also drawn to more radical aesthetics, such as horror movies, which are basically the antithesis of the beauty that Peter engages with at Dior, and more generally in fashion photography. How does horror seduce you, and how do you use the genre of horror in your art?

Cindy: Well, I am a big fan of horror movies, not just because I like to be scared but because I find that whole genre funny too; it’s very entertaining. I suppose a lot of that comes from knowing it is all artificial, so you feel safe in realising that.

Peter: Do you find beauty in horror?

Cindy: Not so much real beauty, but I just find that I am not interested in capturing conventional beauty because enough other people do that – I would rather explore things that are harder to look at. And then I try to create it so that this horror world becomes like a beautiful picture. I mean, the ideal scenario is that you see something from faraway on the wall, and it looks beautiful and very seductive; but as you go closer to see what it is, you realise that it’s actually bugs crawling over a corpse. To me, that is funny: it’s like a surprise, but also disgusting. But it’s fake disgusting: I don’t want it to look so realistic that it confuses people into thinking that I’m documenting rotting corpses because, you know, there is enough of that on the internet and in the news we’re exposed to.

Jerry Stafford: So artifice is a very important element in your work.

Cindy: Yes, because I want people to know that these are fake bugs, and it is a fake ass or fake tits or fake blood. So I guess in some horror movies it is very realistic, but it’s entertainment – but that’s not to say I am trying to ‘entertain’ people with my work.

Peter: But that artifice is also very much the culture of our era. I love the fact you use those fake asses and tits and those prosthetics – it is very now. Again, it is a confrontation. I was wondering: when you did your ‘society pictures’, did you get any reactions from society women?

Cindy: I had some cases: astute and aware women who would look at that show and then congratulate me and say, ‘I can see myself up there.’ But they weren’t angry, saying, ‘How dare you!’ Then again, there were also a lot of women who totally did not see that connection. But so many people told me that they really knew those particular women. Someone said that the mayor of Rome looks like one of those characters!

Jerry Stafford: Cindy, there’s this ubiquity now regarding plastic surgery and the surgical interventions on the street that you have exploited in your work. And Peter, you’re obviously working in an entirely different category of appearance enhancement, but I was interested to know how you both feel about plastic surgery?

Peter: Plastic surgery has become almost as accepted and commonplace as an eye shadow or a lipstick. Or tattoos. In fact, everything to do with transforming the state of your body is very accepted now, which I think is a great thing. It is a revolution. It is not always very well done or thought out. But the possibilities are there, and it is a free world, and everyone has the freedom to do what they like.

Cindy: Somebody told me about a TV show I have to look up called Botched – it’s about all these botched plastic surgeries and it sounds so interesting. There was someone on it who is trying to transform himself to look like Justin Bieber…

Peter: When you look back in history, similar things have always happened, like when corsets became so tight that women died.

Or foot-binding in Asia. And the hair things that people would do: the removal of all eyelashes and brows… all in the name of beauty! What about make-up for men?

Peter: There’s a lot more of it than you first imagine.

Cindy: But it is still not considered as acceptable?

Peter: It is like the skirt for men. In a way, it has been tried over and over again, but just the term ‘make-up for men’ is not so good; it needs to be referred to more like grooming. I mean, it is all marketing anyway. There are a few brands doing really good grooming for men: I know Gaultier did something, but it often becomes very ‘tata’, a bit gay. They were great products but for a very effeminate male.

Cindy: So it is being geared towards a certain audience… When did Dior start creating make-up?

Peter: Oh, very early on. When Christian Dior did his first shows he associated a perfume with his collections. He was very much inspired by flowers. So there was perfume already; and then I think after one or two collections he started bringing out a lipstick and then nail polishes. It was step by step. I don’t know when they started doing a full collection; I think it was the late 1960s when they had proper products. They started working with Serge Lutens, and he did some really amazing Dior campaigns – total transformations.

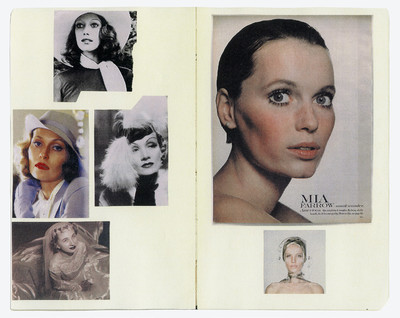

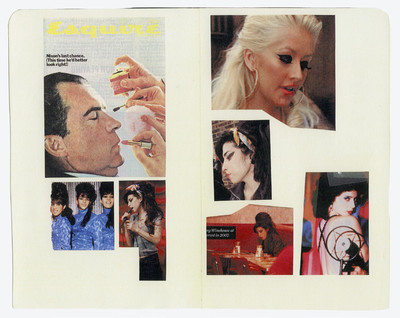

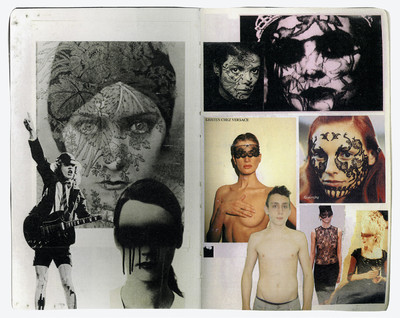

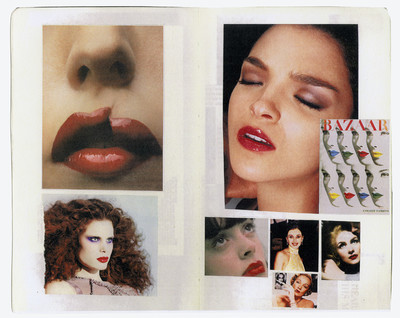

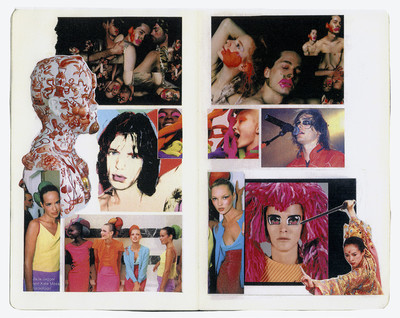

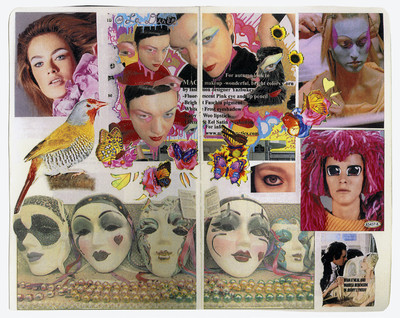

Jerry Stafford: Just looking at the walls here in your studio Cindy, with all these cosmetics advertising pages. Have you used this imagery as a source of inspiration in your own works? Like the poses or gestures, for example.

Cindy: I was really influenced in the late 1970s and early 1980s by those exotic French magazines, things like L’Officiel. I saved some of the magazines and ripped out pages. Some of them were close-ups of women’s faces, so I am assuming it was for their specific look. I was mainly curious about those images where it’s about the use of the make-up, as opposed to just how the make-up is used, like pictures of nail polish…

Jerry Stafford: When you make yourself up for your own portraits, do you use both commercial and theatrical make-up?

Cindy: Oh, yes.

Peter: It’s amazing to hear that you do all your make-up yourself. Have you felt that over the years you have become very proficient as a make-up artist?

Cindy: No. I mean if you look up close… When I work with someone they tend to be much fussier about getting perfect make-up, especially with high-definition pictures. But, a lot of my stuff is also about letting the artifice show, seeing the imperfections. I like it to look heavy, because if I go too natural then it just looks like my own skin tone.

Peter: Do you keep all your old make-up?

Cindy: I have some eye shadows that are probably 30 years old, and I still might even use them for work. But most of it I just try to throw out because now I know it’s not good to have mascara that’s more than a year old. But there are some things I keep for sentimental reasons; I have a kohl pencil from the early 1980s.

Jerry Stafford: Cindy, your first collaboration with a brand was with Comme des Garçons. When those images were communicated to the fashion world, I think it was the first time they had seen make-up used in that way in a fashion context. Peter, I’m sure that you experienced those images in a particular way.

Peter: I was very surprised when I saw them. I think that even Comme des Garçons were surprised by those images, weren’t they?

Cindy: I think so; I think they liked them.

Peter: You really didn’t expect to see that in a fashion context, but then it was like, ‘Ah, Comme des Garçons, they’ve done it again.’ You’ve also collaborated with Balenciaga, and Chanel. How do you deal with things that are not anonymous objets trouvés? Is it constricting?

Cindy: Yes, it shocked me how constricting it was. The Balenciaga people were very helpful, but some of those jackets and things were so tight on me. I work alone, and I remember trying one jacket on that made my shoulders really hunched and then I couldn’t move my arms. The only way I could get it off was by sitting on the sleeve and yanking my shoulder out, because it was like a straitjacket.

Jerry Stafford: That must have been interesting in itself, as the projection of a certain kind of identity you were trying to explore, that of a fashion brand, and how that only literally fits a certain type of body shape.

Cindy: With Chanel, they had given me a selection of 50 or 60 different looks over the course of time. Knowing things were going to be tiny, I looked for outfits that were relatively loose, like a chiffon dress, but when I got it and tried it on, the chiffon was the exterior part, and there was an interior part, a corset kind of thing and then a beaded thing on top which was so heavy. I could get it on, but I couldn’t zip it up. I couldn’t even hook the top of it because the arm and the beaded part were so tight. In the photograph I’m standing there looking really pissed off because I can hardly move without the dress falling off my shoulder. So it really informed the pictures: I look really pissed off and angry, just stood cursing Karl Lagerfeld!

Peter: How about the make-up in relation to all the different Chanel clothes?

Cindy: I made it really simple on myself because I was so afraid of holding onto any of those precious pieces for any length of time. I didn’t actually wear any make-up; I did all the faces digitally, just slightly altering the eyes or making them a little smaller, or tilting them at an angle or elongating the nose – really subtle things. Or just shading the face to make my face look more haggard, or in one case to make me look really old. That was the first time I had ever done digital make-up.

‘Some of the things I have taped up on my studio wall, like the beauty ads, are to make me think about quite how fake they look.’

Jerry Stafford: Is this something you both find challenging, the fact that there is so much post-production, particularly in corporate advertising imagery?

Peter: I really try to fight all that because I think it totally deforms the image and the skin texture. It is a challenge because, for example, with a mascara ad in the UK at the moment, if you digitally enhance the lashes then you have to state that on the advertisement. The challenge is to not use any fake lashes and to do the thing yourself. I worked on the print advertising campaign for Dior, and there is no faking. It is all real: layers and layers and curling and the lashes were separated, and it looks great. And this was a big challenge. I feel that now the business is all about smoothing everything out, not just make-up but fashion too. Every wrinkle or line has to go.

Jerry Stafford: Cindy, is that an area you might explore more in a future series, the possibility of digital distortion, rather than doing it with prosthetics?

Cindy: I probably will. Some of the things I have taped up on my studio wall, like the beauty ads, are to make me think about quite how fake they look, and how I would like to explore that in my work. I mean, I still want it to look obvious; I’d probably do it like a statement of that kind of photoshopping in itself.

Peter: Looking around your studio, you have so many different outfits and accessories. Are you constantly on the look out for clothes?

Cindy: No, a lot of the stuff you can see right now I bought when I was in Morocco, thinking I was going to do a Moroccan project, and then some of them, like an Ungaro dress, are left over from the ‘society portraits’.

Peter: Do you find these in thrift shops?

Cindy: There’s a place uptown where rich old ladies donate their stuff – that’s why the Ungaro dress was there.

Peter: You seem to have lots of vintage pictures of Mexican wrestlers on your walls right now. Is this something you are interested in, moving into more masculine representations?

Cindy: Not wrestlers, but I was thinking about doing a series of men. But that would be complicated: I will probably have to have wigs made and then think about the male characters I might want to portray. When I was doing the Untitled Film Stills, I tried to introduce some men but they just looked like silly clichés; I couldn’t figure out any poignancy or any emotional depth. That’s why with female characters I can relate to what is disturbing them or whatever.

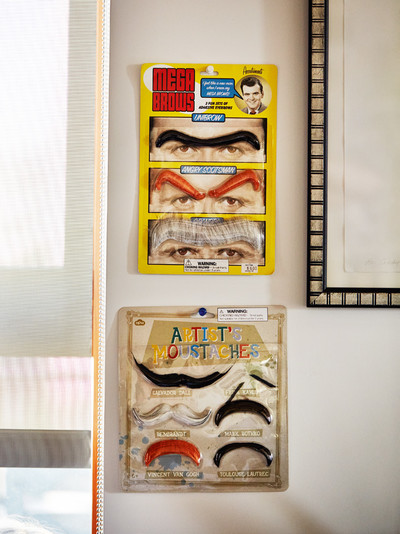

Peter: That is where men and make-up can so easily look fake, unless it is clowns or tribal warriors – when it becomes a disguise. But if you try make-up for men, whether it’s natural or a fake moustache, it always ends up looking odd.

Cindy: More like a mask.

Peter: Like trying too hard… The last question I had for you: When you go out and you put on make-up, is there is a moment when you have to stop applying it so you don’t turn yourself into a Cindy Sherman character?

Cindy: [Laughs] Yes, and it’s tricky getting older. With a lot of make-up, under certain light it can look really bad. It’s always a question of striking that interesting balance between being me and becoming one of my characters.