Louis Vuitton’s Faye McLeod and Barneys’

Dennis Freedman can make you stop in your tracks.

By Jonathan Wingfield

Louis Vuitton’s Faye McLeod and Barneys’

Dennis Freedman can make you stop in your tracks.

Louis Vuitton’s Faye McLeod and Barneys’ Dennis Freedman can make you stop in your tracks.

‘The creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.’ So said Marcel Duchamp, addressing the 1957 Convention of the American Federation of Arts in Houston, Texas. Few creative acts are subjected to quite so much public interpretation and scrutiny as shop windows; and few shop windows generate quite the reactions as those belonging to Barneys’ New York flagship on Madison Avenue, and Louis Vuitton’s staggering network of 467 stores situated across the globe.

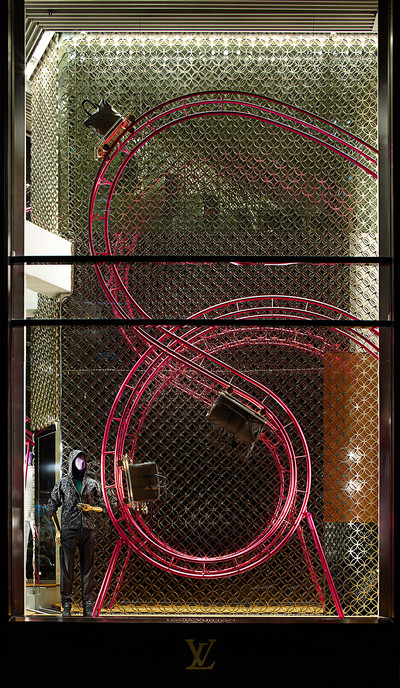

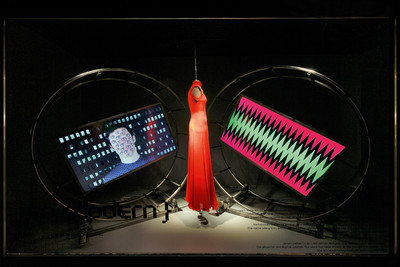

Inspired by art installations and opera sets, production design and 3D imagery, kinetic movement and mechanical engineering, the windows created by both Barneys and Vuitton demonstrate how, when the boldest creative ideas and the latest technologies are refracted through the prism of a luxury brand, they go way beyond simply channelling the zeitgeist and begin to actually set its agenda.

Following his 20-year tenure as founding creative director of W, Dennis Freedman took his reputation for collaborating with artists and photographers to the next level when he joined Barneys as creative director in 2011. Since, Freedman has carved out a strong identity for Barneys as a department store with personality and values. Drawing upon an eclectic mix of cultural references, techniques and observations, every six weeks Freedman transforms its windows into an unpredictable series of sometimes dark, sometimes subversive, and always eye-catching moments. In 2014, a live breakdancing elf performed among psychedelic mushrooms in Baz Dazzled, a collaboration with film director Baz Luhrman, whereas earlier in the year a series of powerful Bruce Weber films representing the struggles and triumphs of transgender individuals were screened across Barneys’ windows in support of the LGBT community.

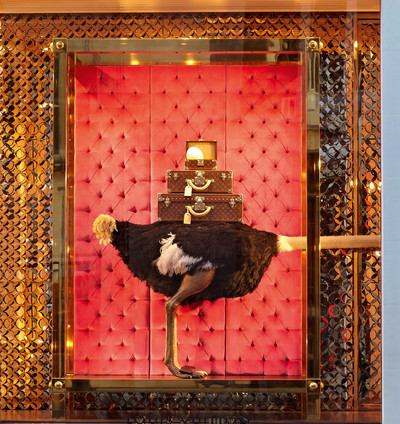

With previous experience at Topshop and Selfridges, Glaswegian Faye McLeod has a long and varied history of windows that came together when she was appointed visual image director of Louis Vuitton in 2009 (and of LVMH in 2012). Working between studios in New York and Paris, her reputation at Vuitton has been forged through an unparalleled expertise in translating the spirit of the brand’s collections – previously those of Marc Jacobs, and now those of Nicolas Ghesquière – via her own highly imaginative and whimsical aesthetic universe. Whether it’s ostrich eggs or a waxwork model of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, her consistency in the quality of execution is always exquisite. No small feat considering the mind-boggling number of stores her creations are rolled out to.

Faye, along with her right-hand Ansel Thompson, invited Dennis and System over to Louis Vuitton’s Visual Image Studio in midtown Manhattan to discuss the power of polka dots, collaborating with artists, and how life would be tough without Google.

‘At Vuitton, the window concepts are used in our 467 stores. It’s impossible to expect everyone to interpret them the same way - but that’s a good thing.’

Jonathan Wingfield: Window displays have the potential to affect different people in different ways. Yet the work is utterly dependent on the spectator’s perception. So let’s start by discussing this idea of your windows being open to infinite interpretation.

Faye McLeod: At Vuitton, the windows we create are incorporated across 467 stores, so you obviously keep the perception of the customer front of mind. But because both our customers, and any potential viewers, are so widespread and diverse, it’s impossible to expect everyone to react the same way – but that’s a good thing, too.

Dennis Freedman: For me, any successful artistic endeavour has to have ambiguity; it shouldn’t be an easy read. My starting point is that the viewer’s perception of the Barneys windows will reflect their own personal experiences and visual acuity, and it’s that range of interpretation that I find exciting. If you think about William Eggleston’s photograph of a peony in his book The Democratic Forest1, you can imagine that a lot of people will look at it and see a beautiful flower. But then in her introduction to the book, the great Southern writer Eudora Welty refers to that same photograph as ‘a bloom so full-open and spacious that we could all but enter it, sit down inside and be served tea’. The challenge is to create something that allows for multiple levels of interpretation.

Faye, the sheer scale of how Louis Vuitton’s windows are rolled out is extraordinary. Does that scope for potential interpretation inform the creative process, or do you consciously try not to become too influenced by it?

Faye: Because of the number of stores we’re creating windows for, repetition is key. Repetition of concept, of production, of quality, of impact, of interpretation. Aside from the obvious amplification of the idea, at Vuitton we are really exposed to how much beauty resides in repetition.

Barneys’ windows present an interpretation of what designers and brands create. Dennis, do you feel a responsibility to those brands, to respect their DNA or is your commitment only to highlighting Barneys’ point of view?

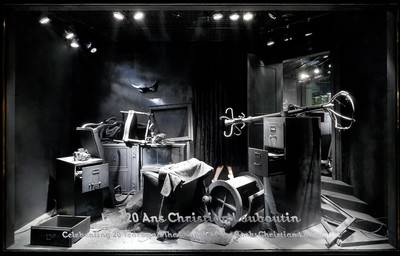

Dennis: It’s both. When we started collaborating with designers I felt strongly that the windows should be neither a reflection of what the designer nor we at Barneys would normally do on our own. You always hope that the combination of the two creative approaches produces something unexpected and original. One of our first collaborations was with Christian Louboutin. Christian has a theatrical and humorous side, but I was more interested in exploring the danger and sexuality within his work. In one window we created a disc, eight feet in diameter, from which hung a large silicone cast of a woman’s torso. The woman was bent over and flame-red hair was cascading to the ground. She was surrounded by black, red-soled Louboutins, all circling her head at different speeds. Now some people might have looked at that window and thought, ‘What a strange tableau’. Others might have seen references to Cocteau and other Surrealists. But I hope that some viewers saw something darker and more mysterious in this woman’s sexually provocative pose. Again, it’s all in the spectator’s mind.

Tell me about any specific window displays or broader visual elements from your childhood that you now recognize as somehow informing your work today.

Faye: I find that you always end up back at the beginning – usually subconsciously. My mum will see the windows I’ve done and often recognize things from my childhood. She’ll say, ‘You know, you used to love collecting ostrich eggs, and when we lived in South Africa, you always loved the safari’.

Dennis: I went to Penn State University, which is better known for engineering, agricultural studies and its football team than for art. I focused on what was going on in New York at the time, and started doing large-scale installation pieces. At one point I decided to cover the entire campus with polka dots: I bought these huge sheets of foam and dyed them all orange with clothing dye, cut them up into thousands of pieces, and then one night went out and covered the whole campus with these pieces of orange foam. I wanted to create polka-dot grass. I didn’t know [Yayoi] Kusama’s work at the time. Your collaboration with her a few years was so impactful. I guess I’ll always be a sucker

for polka dots.

Faye: That’s funny. I’d love to see that.

Dennis: Another time I wrapped up my entire art-history classroom – the chairs, the walls, the slide projector, everything – in brown kraft paper. I wanted to make it impossible for the professor to teach class that day. It was a period of time when I could just let my imagination run free, and the irony is that all these years later I’m returning to that sort of work.

‘I’d never designed windows before coming to Barneys. For me they were simply large contained spaces that held infinite possibilities.’

Windows appear to be the combination of many disparate visual elements – art installation, opera and theatre sets, film-production design, still imagery, 3D experiences… Are you constantly bathing in all these references?

Faye: Our eyes and ears are always switched on. It’s not so much a case of channelling one specific thing, it’s more about being aware of what’s going on, just seeing every type of performance and theatre set, and cinema obviously. We recently went to see Kanye live in L.A.; he was keen to show us his stage set. It was fascinating to see how Kanye combines the backdrop of the creative set with the concert performance; how he choreographs the lighting and everything. It was kind of like experiencing a giant window in the middle of a stadium in L.A.

Dennis: I find that it’s just as inspiring to spend time in the New York State Department of Motor Vehicles as it is in the Museum of Modern Art. What’s interesting are the two radically different experiences: one seemingly mundane, the other high-minded. I always try to avoid the middle. For example, I’m drawn to minimalism – like a Richard Tuttle Wire Piece or a John McCracken polished-resin plank. However, at the same time the work of Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt fascinates me. He creates these extraordinary, deliriously baroque religious altar pieces made out of tinfoil, candy wrappers, beer cans and glitter. The two extremes feed into the work we do at Barneys.

I’ve noticed you both refer to your work as ‘windows’, and never ‘window displays’. Is that a conscious decision?

Faye: I banished the term ‘window display’ from our studio! I don’t consider what we’re doing to be displays; I prefer the term ‘window concept’.

Ansel Thompson: That old-school world of mannequins and window displays just seems really dated. That’s why I’ve always admired what Dennis is doing, because his windows ask different questions about what a window display should do.

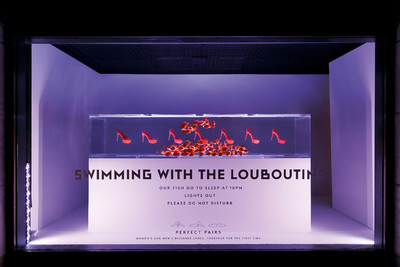

Dennis: When I came to Barneys, I had never designed windows before. So for me they were simply large contained spaces that held infinite possibilities. Our goal was to bring the windows to life. One reference point is the work of Arte Povera artist Pier Paolo Calzolari, whose sculptures often incorporate refrigeration units that generate a delicate coating of frost on their surfaces. He talks about ‘activating the space’. At Barneys, we’re trying to ‘activate’ our windows by using sound, kinetic movement, live performance and other things. In one instance we built a 10-foot-long aquarium and filled it with rockfish that swam around suspended resin Louboutin shoes. Of course, we chose fish whose colour matched the shoes.

The word display seems almost too passive.

Dennis: Totally passive. Yet I realize that if I were working on the same extraordinary scale as Faye, it would make this kind of experimental work almost impossible. It’s very time intensive, very risky, and it can easily fail. But I like that it can fail.

Faye: I agree. I think making mistakes – or at least having the freedom to potentially make mistakes and learn from them – is vital to the whole process.

‘If I were working on the same scale as Faye, it would make this kind of experimental work impossible. It’s time intensive, very risky, and can easily fail.’

Give me an example of a mistake that’s occurred.

Faye: We’ve been burned a couple of times where we’ve come up with an idea that, in the context of the studio in Paris, seems amazing. But these ideas can have other meanings in other contexts…

Such as?

Faye: We did a window with paper clothes, which didn’t go down so well in Asia…

Ansel: …because it’s a funeral tradition there!

Dennis: One time we were using these custom-designed black lights that were switching on and off, but what we didn’t realize was that they were building up intense ozone within the windows, which subsequently set off the store’s fire alarms. We had to come up with a venting system really quickly, but that’s all part of the thrill of doing this work.

Faye, one of the key distinctions between your work and that of Dennis at Barneys is your continual collaboration with the Louis Vuitton creative directors. Can you tell us about that dialogue?

Faye: We are really very mindful of translating the creative director’s vision into the windows; we take all the direction we can, because it’s impossible to get it right straight away. We’d been working with Marc for a long time, but now with Nicolas and Kim Jones, it’s a different process.

In the case of Marc Jacobs, your collaboration extended beyond the windows to creating those fantastic show sets, like the train and the carrousel. Is that happening with Nicolas Ghesquière?

Faye: Yes, we work on the sets with Nicolas and his team.

Ansel: Marc was very much about the seasonal moments, whereas Nicolas is more about the continual development of a process; it’s a language, there are chords, and it develops over a longer period of time.

Faye: The fact we’re building this new language and this new Vuitton universe is really beautiful; we are constantly learning, and turning to innovation for the answers. As everyone knows, Nicolas is a real innovator…

Ansel: …and he’s genuinely interested in technology.

Faye: For us, we are constantly trying to update, to push things forward, to innovate. It is interesting at the moment, all these tech companies are looking for fashion people and all these fashion companies are looking for tech people. And if only people grasped that if you want fashion and tech, you need to have fashion and tech together. You can’t get one without the other, that’s why you need to build a team that combines different types of background and experience.

Tell me about your respective teams. It seems that balancing creative, engineering, and technical skills is key to producing successful windows.

Ansel: We’re 14 here in New York, and 12 in Paris.

Faye: But I still consider us to be a small entity, and I like it like that. I think that independence is really important; Michael Burke and Delphine Arnault have really supported us having the space in which to create and come to projects with different perspectives. When you’re so deeply entrenched in a brand, it can sometimes be challenging to see things with an objective eye, but for us, breaking those rules comes quite easily.

Dennis: At Barneys, we only have six people on our team, but without all of them I couldn’t do my job. I have never worked with such talented people. They are passionate, obsessive and thankfully

don’t seem to need much sleep. When I was building the team I looked for people who could both solve problems and make things work. We build most of our windows in our studio in Long Island City. This might surprise you, but the first person I brought on as a consultant was an inventor and scientist from the MIT Media Lab. When I went to meet with him, I discovered that the building he worked in was filled with biochemists, scientists and doctors. In one corner I noticed an engineer adjusting a cage he’d made. Inside was a plastic baby doll. It turned out that he was developing a device to help babies fall asleep. For him of course, this was all a means to an end. Something pragmatic. To me, the sight of a plastic baby doll rocking in a wire cage was something visually provocative.

Faye: It’s about approaching the same problems in different ways.

Dennis: Exactly. I know that whole right-brain-left-brain idea seems pretty outdated now, but these scientists and engineers seem to me to be primarily technically minded.

Ansel: That’s a bit like me. I don’t come from a visual background; I come from a product-design background, which I guess is more technical.

Faye: You are way more engineer than me! My brain works very much with visual memory – I can remember every Barneys window, every Bergdorf window. I can get very commercial and product-based, really in line with the vision we want to follow business wise; Ansel will push against my ideas and I will push back, then we end up getting to an end result that we’ll develop in whatever way, building models, rendering, sketching, plasticine…

‘When I was building the team, the first person I brought on as a consultant was an inventor and scientist from the MIT Media Lab.’

Collaboration with Christian Louboutin

Barneys New York, Madison Avenue, New York, Fall 2011

So written into that process is the tension between creative feats, technical feats, engineering feats and then the feats of scale and production…

Faye: …and then the commerciality that wraps around that, which is the core purpose.

What is the common trait across all your team members?

Dennis: Curiosity and obsessiveness.

Faye: [Laughs] …is that why you like me so much?

Dennis: Yes! I’m pretty OCD, too.

Give me an example where your OCD behaviour has been put to good use in your work.

Dennis: We once did this apocalyptic window and everything was covered in a layer of black pigmented dust. A mechanical cockroach was supposed to be jumping slightly from a sofa, but we just couldn’t get it to jump in a convincing way. It got to about two in the morning and most people were fading, but I realized then that the few who were still trying to make this work, the ones determined to get that damned cockroach to jump, were the ones I wanted on my team. You know, most spectators were not even going to see this cockroach – it was tiny and almost hidden in the corner of the window – but to me it was a key element. And if only one person noticed, it was worth it.

Faye: It’s that attention to detail we all love about you!

Dennis: So which of you two came to Vuitton first?

Faye: I came first. Ansel took some persuading! We totally respected the existing structure and were able to build a really diverse team. But what’s important to us is to feel free; we’re quite rebellious within a French organization. It’s something that Mr. Arnault really understands; he’s the one who has been with the CEOs, really helping us to get to a place where we can push ideas and think differently.

Ansel: There has to be some kind of mischievousness there.

Can you give me an example of something that you thought was perhaps too radical to be accepted in the context of Vuitton, but that actually ended up being championed by the company?

Faye and Ansel: [In unison] Kusama!

Faye: I basically had to find an art collaboration for a window. I felt that it had to be with a woman because before I joined I felt Vuitton’s windows were often quite masculine. I also wanted it to be a Japanese artist because we go there a lot and we find it so visually stimulating. Whenever we get stuck for ideas – and we get stuck quite a lot – we jump on a plane and go to Tokyu Hands for a rummage around! [laughs] Anyway, I really wanted to work with Yayoi Kusama. We love her work and it felt right.

Ansel: She can make people feel quite uncomfortable and we liked that.

Faye: So we flew over to Tokyo again because we were told that she’d only ever agree to doing anything if she meets you and connects. We were both a bit terrified, but it turned out to be one of the most inspiring days of my life. We kind of disappeared off the planet for a day to be in her world: we sat and watched her paint, and she took us through all of her canvases. When we got up to leave her people just said, ‘She will work with you’. Everything else followed from there, but the windows came first.

‘The effect is immediate: we can unveil a window in Paris on early Monday and by the afternoon I can sit and look at pictures of it all over social media.’

And that’s an exception?

Faye: The product usually comes before the windows. But then we said to ourselves that we didn’t want to put any products in the windows. We worked really closely with Kusama and her teams: we’ve got this fantastic Japanese guy in Brooklyn who does a lot of sculpting and he agreed to do the Kusama waxwork doll.

Ansel: She was really open and intelligent and wasn’t precious. As Faye says, it was all about the connection.

Faye: Yes, there have been a few magical moments when you really connect with the people you are collaborating with. Like when Ansel said to me, ‘We keep doing these art collaborations, but what about architecture?’ We had the chance to meet Frank Gehry because of the Fondation Louis Vuitton, so we went off to L.A., just to see if we could connect.

Was Frank Gehry’s Fondation building completed by that stage?

Faye: It was about a year before. I just said to him, ‘We’re here to talk about windows’, and he came back with this really old windows book and said it was his father’s. I still have goose bumps thinking about it today. The amazing thing was watching my team – some of them are these really talented young guys straight out of Saint Martins – working with Frank Gehry’s team, learning their software, and developing their skill sets. It was just magical to be so welcomed into his world, with open arms.

Generally speaking, how far ahead are you working for a project like this?

Faye: We have a design team, a technical team, a production team, and a logistics team all working together in order to get the physical components shipped to destinations all over the world by boat. And because of all of that, we have to work a year in advance. That’s the general timeline for what we call our ‘network’ stores. With the maison stores – in places like the Champs-Elysées, Bond Street, Fifth Avenue and so on – we can be a little more reactive.

Dennis: At Barneys we create a new window every six weeks, but we work on our big November-December holiday windows throughout the year. They tend to be technically and creatively ambitious, so by February or March we are well into it.

The digital world now allows the physical world to be captured, shared and disseminated. Does that inform the way you now approach your windows? Are you conscious of building ‘Instagram-friendly’ elements? Is the ‘windows selfie’ a key to success?

Faye: You can stand outside a Louis Vuitton window and see the number of people pulling iPhones out to take selfies in front of them. The effect is immediate: we can unveil a window in Paris on early Monday and by Monday afternoon I can sit in my New York studio and look at pictures of it all over social media. That’s enabled us to get a better understanding of how far we can push a window scheme; of how we can best balance our view of the brand with that of the audience, and what they are willing to engage with.

Dennis: At Barneys, our strategy is always to amplify one idea across all social-media and digital platforms. The windows are a key component of expanding our branding opportunities. The fact that we incorporate kinetic and performance elements allows us to capitalize on the hunger for video content. Ten years ago, the windows depended on physical traffic; now, we have a devoted digital audience, with over 4 million social-media followers we can reach via the films we make.

Faye: The windows are central to everything.

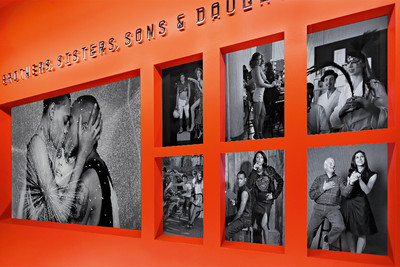

Dennis: That’s right. And the social-media and traditional-press impressions are intended to lead you back to the Barneys website. Right now we have about 3 million unique visitors every month to our site. We have a luxury editorial site, The Window, where we share original content that in turn gives us a presence on another platform. In 2013, we launched the Brothers, Sisters, Sons & Daughters campaign shot by Bruce Weber. It featured 17 transgender men and women, but we not only shared the images and videos shot by Bruce in the Madison Avenue windows, but also on our website in a really impactful way. Those campaign images were shared heavily on both our own social channels, but also by others who were inspired by the campaign.

Faye: The windows you’ve done using film are among the best I’ve seen in Barneys. The transgender windows made me just stop dead in my tracks. I remember getting goose bumps looking at it and texting you immediately to say what an effect it had had on me. What I admire most is that you can be topical, you can push buttons, you can be a little on the danger level.

Dennis: The Brothers, Sisters, Sons & Daughters campaign was particularly close to my heart: it was thought out very carefully and we knew from the start that the images and films we made of these extraordinary kids were going to become the basis of our windows. We wanted people to view the films through the windows.

Faye: We are starting a more digital approach with the Louis Vuitton maison stores and we’d really like to push into new boundaries.

‘With the Kusama windows, you had people with their noses pressed against the glass. We were cleaning handprints off the windows all day.’

Aside from social-media coverage, how do you personally gauge the success of a window?

Faye: When we put Kusama in the windows, you had people with their noses pressed against the glass. You know you’ve done a good window when the guys have to clean the nose and handprints off the windows several times a day!

Can this physical experience extend into a broader cultural experience, one in which windows can live on after they’re dismantled?

Faye: Ultimately, we’re challenging ourselves with giving people something that might get them off their smartphones while they’re walking down the street. I always say the windows are the billboards to a brand. You’re on prime real estate, you should be having fun with it, you shouldn’t be taking yourself too seriously.

Dennis: If I think of the Vuitton windows – and I think about this a lot – those windows will always be implanted in my mind. You’ve defined your brand, you’ve put Vuitton out there, and you’ve raised the level. It’s one thing to show the product – you might buy a dress, you might buy 10 dresses and five handbags – but how does that compare to the overall effect that those windows are having for the brand? And in particular those windows that didn’t even have products in them! I’d say 90 percent of the time we do put product in Barneys’ windows, but we have to be aware that these are huge branding opportunities. Product is not enough; we need to keep reinforcing what makes brands like Barneys and Vuitton so special.

Ansel: Going back to display: it’s not just display, it’s also a cultural experience.

Dennis: Exactly! With the Brothers, Sisters, Sons & Daughters windows, there was no product per se, except that the kids were wearing brands we carry. The important thing that you came away with is that Barneys really stands for something, and I feel that’s an extremely important message to convey. We have our core customers and we believe that they will respond positively to our view of the world.

Dennis, what comes to mind when you think of Vuitton windows?

Dennis: I think that everything these guys do for Vuitton is an expression of extraordinary creativity and attention to detail. That alone says everything I need to know about the quality of the brand’s products. I just look at the details in the windows and it blows my mind to think they’re being replicated all over the world. I will never forget that gold-plated dinosaur – it is embedded in my brain!

Faye: That dinosaur was intense! My friend and I had been to the Natural History Museum and watched as all the kids were completely in awe of the dinosaurs. It got me thinking about how we could do a dinosaur that would leave the same impression on adults as well.

Ansel: We found a factory in China that makes dinosaurs for theme parks.

Faye: One of the important things to know about our working process is that we don’t use the same suppliers all the time; it’s about finding the right supplier with the right savoir-faire for the task in hand, no matter what country they’re based in. When we did our Arrow window we wanted to get the feathers dyed in the very best pigmentation, and that meant India. The teams research in order to get the very best end result, whether that’s for the creative or the production or pigmentation.

Dennis: But that’s the real excitement of when you’re imagining something: we’re both lucky enough to work with teams who are committed to producing the very best result. When we did a window with Chloé, we featured a surrealist dress designed by Karl Lagerfeld that had an image of a showerhead embroidered on the front. I wanted to show the dress encircled by a continuous stream of water. My team tracked down a water filament in a shopping mall in South Korea and then found a factory in Texas to construct the shower.

Faye: [Sighing] What would we do without Google?

Dennis: What would we do without Google?

Faye: Apple and Google, without those two we would be in tricky waters!

Dennis: Tell me about it!