Why Rem Koolhaas’ new Repossi store is bringing revolution back to the Place Vendôme.

By Jonathan Wingfield

Portraits by Willy Vanderperre

Why Rem Koolhaas’ new Repossi store is bringing revolution back to the Place Vendôme.

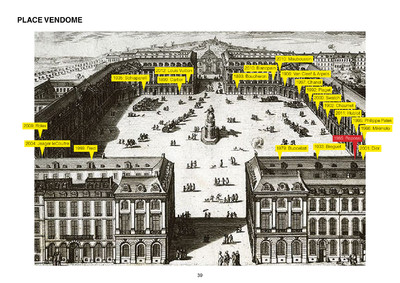

Ever since 1893, when Boucheron opened a store at number 26, Paris’ Place Vendôme has been to fine jewellery what Savile Row is to tailoring, its harmonious Corinthian pilasters and columns providing the ideal backdrop for the biggest names in this most rarified of retail experiences.

Repossi’s store at number 6 was the seventh jeweller to arrive when it opened in 1985. The house’s third store after Monte Carlo and its historical base of Turin, it is today at the heart of Gaia Repossi’s profound reassessment of her family business. It began with design. Gaia, who became creative director in 2007, creates jewellery almost like an industrial designer would, constructing pieces that she then strips back to their essence to reveal the purity of forms. This less baroque approach is now part of her broader questioning of the very fundamentals of jewellery – from why it is made to how it is sold.

To help foment a revolution in jewellery retailing, Gaia got in touch with Rem Koolhaas’s OMA architectural practice with a view to giving number 6 more than a spring clean. No stranger to conspiring with fashion brands (OMA has been working with Prada since 2001 and recently completed work on the new Fondazione Prada in Milan), Koolhaas relished the opportunity to bring his wide-ranging, deep-thoughts approach to an often hidebound consumer experience.

Gaia and Rem invited System to take an exclusive look behind the scenes of their collaborative process, and get first eyes on how the new Repossi store, which is set to open in January 2016, will look and function. We then gathered in OMA’s Rotterdam HQ, along with OMA partner Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli to discuss the future of shopping, Gaia’s Instagram account and why three’s the magic number.

Jonathan Wingield: Gaia, what initially attracted you to the idea of collaborating with Rem and OMA?

Gaia Repossi: I called Rem and his team because I knew they would want to break codes and create a jewellery store that is everything but generic – an antidote to what Rem refers to as ‘junkspace’. OMA constantly proves its ability to reinvent established methods, and jewellery is virgin territory for architecture. So many other fields have gone through reinvention, why not jewellery?

Rem Koolhaas: I think there is a tendency in contemporary culture to be totally redundant, which oppresses materials and oppresses environment, and so on. Ultimately I think that contributes to widespread dullness and a lack of contrast, which is very important to confront and interrupt.

‘Jewellery can be a boring field with little room for creativity beyond marketing targets, but working with OMA feels more like an artistic experience.’

Is questioning the status quo something that OMA does in any given domain?

Rem: The way you put it seems a little bit May ’68 reactionary, and that makes it difficult to wholeheartedly say, ‘Yes, we question everything’. We try to be a little subtler and so we simply try to work in different ways. We’ve always realized there are certain things that you could change, but then we also realize that disruption simply for the sake of it would be irresponsible. We like to operate, not between conservatism and disruption but between a historical consciousness and modernization. We modernize when it makes sense to.

Gaia, are there specific aspects of Rem’s rhetoric you were keen to bring into this project?

Gaia: Rem’s S, M, L, XL book contains some interesting thoughts about fashion and about the place that shopping holds in society. A lot of what he wrote makes sense to me: you make a product, you are responsible for it; you cannot just put it out there and add to the junkspace.

Image courtesy of OMA

S, M, L, XL is now 20 years old. What role does shopping play in society today?

Rem: Shopping is changing so fast. In the past 15 years we have obviously seen the emancipation of Asia and the Middle East, and we’ll soon see the emancipation of Africa, too. With this comes the many possibilities of articulating these influences and these potentials. I’m really happy that we started to pay attention to those places at a time when there was little focus on them. Today, of course, it’s staggering what can be done in those places.

Online shopping has obviously had a fundamental impact on the way society consumes, but how does this affect the thought process of an architectural firm like OMA?

Rem: We were discussing this with Gaia earlier today. What’s interesting is that people come more prepared now.

Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli: Basically we don’t think that digital will ever replace physical because the two offer such different experiences. The e-commerce domain is principally based on presenting products, accessing those products and then eventually buying them. OK, so you have these huge digital databases, but then you want to go to a store and actually touch and feel them, and understand where the product is coming from…

Rem: …and what the narrative is behind that product.

Ippolito: This inevitably affects the way that physical spaces operate: you often have much less merchandise exhibited, but it is done in a more curated way. The product becomes a vehicle for the cultural understanding of what has generated that product, from its choice of materials to the creative process.

Gaia: The most popular stores these days are technology stores, which seem to be everywhere. People just walk in, like it’s a museum or a gallery, and hang out and want to experience things that are new every six months, every four months, every month. This new approach is perhaps too extreme for the jewellery industry, but I was really looking for an experience beyond just feeling comfortable on a couch looking at jewellery. The experience is especially poor in the jewellery industry; the more you go high-end and luxury, the less experience you’re likely to encounter.

Ippolito: It is the dictatorship of sales: the profits are always in front of you and immediately accessible. There is no staging of the ceremonial that brings you close to the product.

Rem: I think it is anxiety about the stakes involved. Obviously the more money; the higher the stakes.

Do you think that anxiety is palpable in luxury shopping?

Rem: Very much.

‘Gaia is one of the first people to have modernized jewellery – not necessarily because she wanted to change it but because she realized she had to.’

Which is quite paradoxical since there is no luxury in anxiety! Gaia, to what extent have you reconciled in your mind the rapport between experience and product display in your store?

Gaia: My initial concern for the store was aesthetic, followed by experience. The difficulty has been in finding the right balance between the physical architecture and the existence of the jewellery. I mean, you could opt to go very minimal – though OMA tends not to – or there is the route of presenting lots of complex beautiful aesthetics… but then how does the jewellery exist within that?

Rem: That’s the beauty of this situation: it really is a test, like a laboratory, and you can learn from it. For me, it was amazing to discover that the world of jewellery had such a furious degree of discipline.

Which can obviously be perceived as both positive and negative, right?

Rem: Yes, I was made aware of the discipline and ambition and tradition. When you’re working in fields such as jewellery, it is really nice for history to suddenly become vivid and begin to resonate more. To be honest, prior to collaborating with Gaia I had never really given much thought to jewellery beyond the simple act of giving, so it’s quite revelatory to have a more complete picture.

What elements of jewellery do you now understand better?

Rem: Well, it starts with something as basic as finding myself paying more attention to what are on ladies’ fingers.

Ippolito: I barely knew anything about jewellery before working with Gaia; she really helped define some guidelines. But then we went off and explored the history of jewellery ourselves because we wanted to know how Gaia was changing the perceived normal methods of operating.

What did you learn?

Ippolito: I can certainly say that Gaia has a different way of working from other companies. I naively thought what she did was an artistic exercise around a very precious stone, which is the idea I had of traditional jewellery. Gaia confirmed that jewellery designers normally start from the material – from the stone – and that the design is developed around that stone in order to create the product. Hers is a different approach: she starts from the design – from the idea, almost on a conceptual level – and then you get to the product. It’s a completely different mindset, which allows her to move faster and produce more collections throughout the year. This in turn allows her to think about the rapport between the space and the product in different ways.

Rem: This is also a very important point: all of us are influenced by our desires but there is an enormous pressure from the outside, so even if we wanted to stay the same, we could not because we have to work at different speeds and with different countries and so on. Gaia is one of the first people who has actually modernized jewellery – not necessarily because she wanted to change it but because she realized she had to.

So if you don’t believe in a system, you have to create your own.

Rem: It’s also born out of the sheer acceleration; the way that more collections have to be launched in a shorter time…

Gaia: It’s what people expect, and even that’s not enough for them.

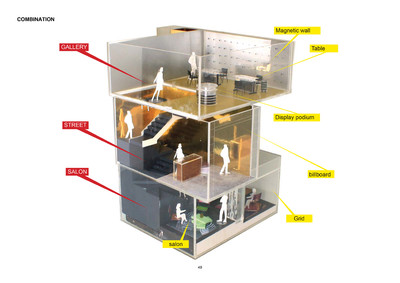

Ippolito: For me, the most revelatory moment in this project was visiting Gaia’s ateliers in Italy and Paris. I got to see things being made in the same ways that they were centuries ago, but they are implemented now by new technologies. It’s the perfect combination and balance of the two worlds and it was extremely constructive in terms of crafting some of the concepts of the store. So where you have a combination of things that are extremely simple, they are just recombined into more unexpected relationships. For example, normally when you walk into a jewellery store everything is very rigid and static, as minerals don’t move. We introduced subtle degrees of movement in the store.

‘Rem came to my office in Paris, looked at the jewellery, and said, If the design is simple I go complex, if the design is complex then I go simple.’

Like kinetic displays?

Ippolito: Yes, exactly. Every single component has a degree of movement that forces you to have a relationship with the product that is constantly changing. And that for us was a revelation because the norm in jewellery is to approach everything with strict symmetry. We had a lot to play with. Gaia, people often refer to your aesthetic as minimalist, almost as an antidote to the traditionally baroque jewellery environment.

Rem: But Gaia, do you consider yourself minimalist? Just look at her hands! [They are covered with rings]

Gaia: I don’t consider myself minimalist, because my designs are complex. Minimalist is just a label. I am attracted by less, but for me that’s more a question of constructing things that are reduced to the essence.

Ippolito: There is something very architectural about your way of working.

Gaia: Well, we’ve found ways of working that place a little less emphasis on luxury and more on design and the expression of shapes and form through jewellery. As you discovered, it starts with a structure rather than a stone.

Tell me more about the first conversations that you had together.

Gaia: Rem came to my office in Paris, looked at the jewellery, and said, ‘But this is architecture!’ He then said something very straightforward: ‘If the design is simple I go complex, if the design is complex then I go simple.’

Ippolito: When we first met Gaia we felt there was a clear affinity between the two companies, and that is something we always ask ourselves, in order to gauge the potential to create something interesting. I remember the conversation: we were talking about some references hanging from the wall in her office, such as movies, sculpture, some furniture, something with Le Corbusier. I just wanted to know more; I acted like a sponge. As I mentioned before, we had to fill the gap about our lack of jewellery knowledge, but we also looked into Gaia’s personal tastes and interests, as well as interviews she’s done. We actually borrowed pictures from her Instagram account – mainly art and architecture – to create these kind of image campaigns. It was all part of developing tools in order to establish a dialogue.

Gaia: It is a very unusual way for architects to work: they absorb you for a couple of months, in the same way that maybe a film director would. Following that period, they started responding to my references and sharing their aesthetic.

Were you aware of that absorbing process even taking place?

Gaia: Not really because it was the first time I’d worked with OMA. It was a discovery, but a beautiful one. I generally love to overanalyse things and this became a very deep analysis of the environment in which I work. The collaboration with OMA goes beyond just the store; we are reinventing the whole identity of the brand in the context and environment of the jewellery world. As I was saying before, it’s generally a pretty boring field in which there is little room for creativity beyond marketing targets. But this feels more like an artistic experience because I consider OMA to be artists.

Image courtesy of OMA

Can you give me an example of how OMA challenged the confines of the jewellery field?

Gaia: Within the jewellery industry you usually make a store that is described as an écrin – like the little box for a ring. So the traditional wisdom is that the interior has to be soft, and it has to be full of comfortable materials. In one of the first research books that the OMA studio team created for us during the project, they made a collage of what they called a ‘generic jewellery shop’, entitled What We Don’t Want. We then started by discussing speed and really got to the heart of analysing how speed determines the jewellery-shopping experience.

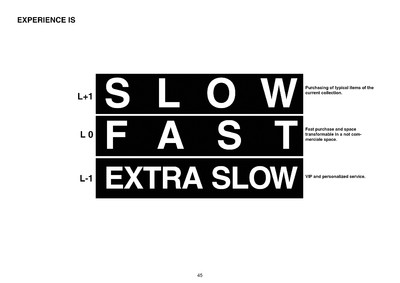

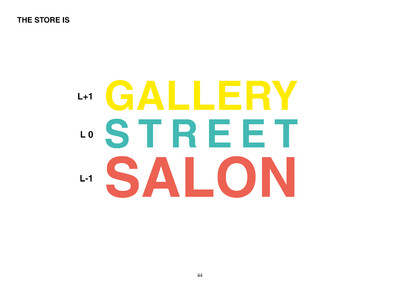

Ippolito: Each of the three floors of the new store is a different experience and has a different speed. Firstly, the basement is the most intimate, the space where you spend the most time and are attended to the most.

Gaia: The basement is actually closest in function to the classic écrin, but it is not at all that experience. Nonetheless, I thought it was still important to have a space where customers could isolate themselves and discover the more complex jewellery pieces.

Ippolito: Secondly, the ground floor is where you might have a rapid consumer experience: you know which products you want, you buy them, you leave.

Gaia: It has a standing counter that allows for five-minute sales.

Ippolito: Rather than the ground floor simply having an outward-facing window in which to display products, we refer to it as an extension of the street. It can offer a real void, an empty space, which on the Place Vendôme is the most surprising and luxurious thing you can find. We’ve introduced a system where on the ground floor the walls rotate so they can have different functions and different backdrops. It’s one of the key kinetic elements we mentioned earlier.

How does the wall rotate?

Ippolito: The interior wall is made of strips that can rotate into three positions. In position one, you have a huge visual that folds around the entire wall; it could be the brand campaign, or a piece of art or a visual reference.

Gaia: Brand image is obviously really important, so this option is essential. It is the first thing you’ll see from outside.

Ippolito: Then, when the wall rotates into position two, it becomes a different material: a gradient mirror that looks almost like metal and from outside the store creates this void. The third rotation will then reveal products, which are placed within insets in the wall.

‘When the store originally opened in 1985 my mother was pregnant, and now I soon turn 30. Would Freud say something about that? Probably.’

So the product is constantly rotating and only displayed one third of the time?

Gaia: Yes, I love the idea of introducing movement into a store environment that is usually rigid and frozen. This whole system offers an alternative to just having a window with products in it: now it can display the best pieces in the collections; it can show images of them; or it can simply let customers see themselves when they try things on.

Ippolito: Finally, on the top floor is the gallery, there is this intermediate-paced experience where the majority of the collection could be exhibited.

Gaia: It allows you to see everything displayed at once, like a sort of cabinet de curiosités, where the woman can buy anything she sees without much explanation.

I wanted to talk about scale. This project is inherently small, from the medium of jewellery design to the physical size of the store. To what extent does the size of the end result determine the process, the resources and so on?

Ippolito: I think that small scale is a universe unto itself; the deeper you go in scale, the more you discover. In 10 years of working at OMA I can honestly say I’ve never gone so deep into the exploration of a project as I have with this one – we’ve really had to consider the display of every single jewel. I can’t say for sure if there is a direct rapport between scale and effort, it’s perhaps more a mental shift towards another kind of domain.

What about the pace of working on the project?

Ippolito: Speed is a really interesting issue: for this project I think proportionally we invested more time given the size of the store if we compare it to much bigger projects. But those projects often have timeframes that need to go faster simply because the investigation of materials, skills and design was so accurate. So there is actually a sort of reverse proportion between the size and the actual time that we invest.

Rem: I agree; I think that is very well put. I’ve done both houses and much bigger projects and have discovered that doing a house is at least as complex as the biggest project out there. I think it’s a very comparable situation.

Why do you think that is?

Rem: Partly because you discover more and more intricacies and therefore more challenges and more possibilities. But it is also because you have a different sense of responsibility. In the case of Gaia’s store, she can make the decisions directly, and we are talking directly with Gaia, not a committee of 20 people. It naturally becomes more personal and so you feel more responsible for the outcome. It is so precise and on such a traditional human level that there is no escape from going to the very essence of it.

Do you think that with such a small-size project there is a greater importance on editing?

Gaia: OMA is so prolific and can produce 100-page documents in a week and propose you 45 different options, so from my point of view editing was a real task.

You’d get 45 different options?

Gaia: Absolutely. Of materials, staircase designs… Visually it becomes like an artwork: you need time to absorb it, and of course there are references from my work and references from OMA’s work, so the editing for me was very complex.

Ippolito: It’s a very interesting point because as Rem was saying earlier, you develop a personal and intimate exchange during a project. There is a process to developing a specific language over this intense period of exchange, according to the client’s background. So in the case of the 45 options that Gaia is referring to, our engineer develops these in order to actually generate the best exchange possible, tailored to the process.

Do you think creative collaborations require harmony between the various individuals or can interesting ideas be born out of discord?

Ippolito: I would say there is never complete harmony. We had multiple conversations and divergences during the process.

Tell me about some of that.

Ippolito: The choice of materials. What I find really helpful and constructive with a collaboration, though, is that when we didn’t find a solution we would simply exchange references to reach a possible conclusion.

Finally, Gaia, the Repossi store has been on the same Place Vendôme site for 30 years. What does this current deconstruction and reconstruction of the store – and the brand – reveal about your rapport with your own family history and the family business?

Gaia: More than questioning my own family brand, I’ve gone on a kind of personal questioning of what luxury is – or could be – today. It’s something I’ve been pursuing for the past few years; but for longer still, I have been questioning the function, design and utility of jewellery today. I’ve questioned if the next generation even needs jewellery and what luxury might mean for them. I’ve questioned these things in order to offer my family brand something that made sense to me, and that was relevant. With regards to the 30-year historical coincidence, when the shop opened in December 1985 my mother was pregnant with me, and I will turn 30 this March. Would Freud say something about that? Probably. All I know is that I’m very proud to be able to give this 90-year-old house a new direction.