The founder of IDEA Books on why print still matters to some of us.

By David Owen

The founder of IDEA Books on why print still matters to some of us.

George Lucas

‘There is something unequivocally special about reading and researching with physical books and libraries’, filmmaker George Lucas tells us via e-mail from Skywalker Ranch in northern California. ‘It often allows a more in-depth look into materials that may have yet to be digitized or presented fully online. You can find information of a rarer nature and distinctive images that differ from the same top few Internet searches everyone else also sees. The Research Library and its trusted librarians have helped me research film, costumes, hair and makeup for years. On a more nostalgic note, there’s nothing like the tangible nature of turning actual pages of paper, the smell of the print, the substantial heft of a good book.’ That research library, an Arts and Crafts-style building with a skylit dome Lucas helped design, is managed by his trusted librarian Jo Donaldson, who gave us an insight into the galactic storyteller’s reasons for accumulating so much paper-bound knowledge.

David Owen: So tell me your role and job title.

Jo Donaldson: Manager of the Lucas Research Library.

How long have you been in that position?

I started in the library in 1984.

Wow!

I was hired as an assistant librarian. The six-month job turned into a 30-year career. Debbie Fine started the library for George back in the late 1970s. She needed an assistant and then when she retired several years later I took over as manager of the library.

Do you have people working for you?

Right now I have one research librarian and we do basically the same thing: provide research and reference searches to our company and to outside clients in the film and TV industry.

What are the origins of the collection?

Around 1978 George decided he wanted to have a full-time research library and librarian for productions – mainly story research, set, costumes and hair research for films that he was going to be working on.

And has it always been located here in northern California?

At that time George’s company was based in L.A. He subsequently bought the property that was to become Skywalker Ranch. Although he’d lived in L.A. for a while, he really wanted to move to northern California. It’s a rural setting. The ranch looks like a residence, but it was built for commercial use.

‘If you look at the check-out card in the books you pull off the shelves, you’ll see that Alfred Hitchcock took this one out in 1964.’

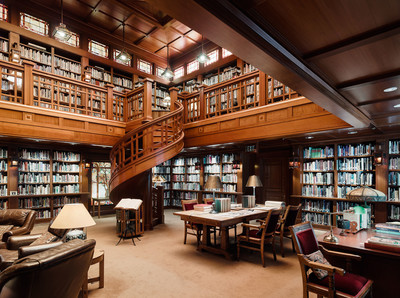

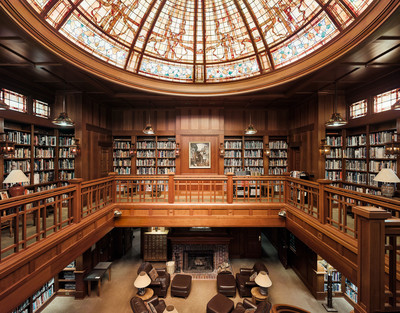

The library is a really beautiful building. Did George design it?

He is a frustrated architect, I think. He came up with all the designs and worked on them with the architects. The main house looks very Victorian in some rooms, but the library has an Arts and Crafts feel. And it is all natural light coming in the dome.

And it’s vast.

We’ve been building our collections for over 30 years and along the way we have acquired two historical collections from movie studios. The old Universal Studios research library was acquired when it closed down in 2000 and the Paramount Studios research library, which had been dormant since the late 1960s, we acquired in 1987. Since our collection started in basically the late 1970s, these historical collections added to our resources a lot. It preserved these historical collections and kept them intact. George is always thinking about that, preserving these book collections.

There must be amazing books…

In the Paramount collection, if you look at the check-out card in the books you pull off the shelves, you’ll see that Alfred Hitchcock took this book out in 1964; and Cecil B. DeMille checked another one in the 1940s. And of course, Edith Head1, the costume designer, used the Paramount library a lot, so there are many books that have her signature on them, thanks to her work with Hitchcock. There’s a book on British cooking that Cary Grant checked out.

This must really appeal to the people who use the library now…

It does. One of the downsides is that so many of our clients don’t have time to actually come and browse the library. Most of the outside clients are in L.A. and they can’t come and look at the collection, so we gather the information for them and send it off.

Is the collection predominantly visual?

We probably have 16,000 books in the Lucas Library collection and most of them are picture books. Years ago someone came to our library and he was looking at the books and he said, ‘This is like the largest collection of coffee table books I’ve ever seen!’ Of course, we do have other books because we do story research for our productions. For all the Raiders movies we have a large mythology section. We just don’t have any fiction in our library.

And is the library itself unique or do other companies still maintain them?

All the studios used to have research libraries like ours. These days there is Warner’s that’s still around, as well as the Fox research library. Disney has a couple of research libraries. What is unusual about ours is that it has continued to grow and expand and acquire material. A lot of these other libraries have had their budgets cut – probably back in the 1970s, the 1980s – which has obviously affected their growth.

‘After you’ve been working on Star Wars movies for 15 years, you kind of know what books production designers are going to want to see.’

Does it feel like you are working in the past?

Over the last couple of years we’ve noticed, because of the Internet and the historical images now available online, that our outside-client requests have decreased. So we are not working with outside clients as much as we used to.

How are you treating that within the library? Are you digitalizing things?

No, we are really not – there is so much. There are also amazing picture files, which are in 500 filing cabinets. They are organized by subject and they have stills that were taken of New York street scenes from the 1930s to 1950s. There are clippings from newspapers and an amazing periodical collection: Harper’s magazine going back to the late 1900s, a whole run of Life magazines. That sort of material is so entirely different to what’s available online.

Of course, if people don’t have time to come in and browse the shelves then they are depending on us more to deliver what they want. There is not that, ‘Oh, turn the page’ and, ‘Wow, look at that image, I didn’t even know I wanted that image.’ Or the chance to look at that book that is next to the book that you requested. It means that they are depending more on our take. Fortunately, after you’ve been working on Star Wars movies for 15 years, you kind of know what production designers are going to want to see; the terrain, the animals, what is going to inspire them…

I’ve been thinking lately how books compare to digital material – it could be generational. We have production designers who come in here and who are in their 50s and 60s and they just go wild for the books. They could stay here all day. But some of the younger artists – although they like books – are comfortable with getting images and references online.

That said, there were younger artists working on the Star Wars prequels and their art department was actually in the same building as our library. Even though they were younger, they did love to have books by their computers. They were drawing on their computers, but they loved having the physical books there, too. They worked on all three episodes and the books would just stay up there. It wasn’t unusual for an artist to have 20 books from our library by his or her computer. Some of the books they had checked out for about eight years!

Giovanni Bianco

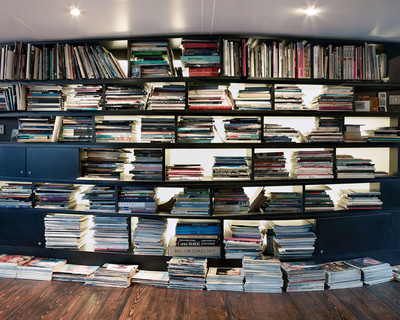

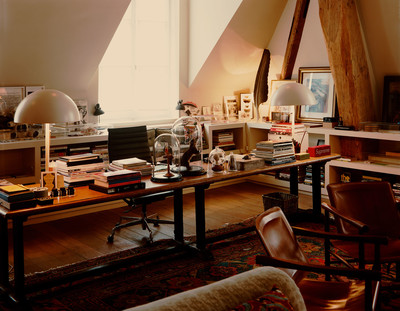

Biography or bibliography? Giovanni Bianco’s life is made of books. Born in Brazil, he moved to Milan aged 23 where he met Gianni Versace and Domenico Dolce and Stefano Gabbana and began his career as an art director. After a childhood when books were an unaffordable luxury, Bianco used his earnings to begin building an impressive library, book by book. When he moved his business to New York, he built a studio in Manhattan that he designed around his book collection. The library is at the core of the man and his work. The 20 or so young designers working quietly away during our interview may have been looking at screens, but the business that employs them was built on print. Indeed, the books may well survive both Giovanni and his company. The narrative arc of the library is shaping up to be a perfect circle: he is planning to establish a foundation in Rio to house the books and bring culture to disadvantaged Brazilians, young people facing the same challenges he did not so long ago.

David Owen: Do you remember the first book you bought?

Giovanni Bianco: Everything started when I was young. I come from a very simple family in Brazil. I started working with my father when I was five years old, selling fruit in the street markets. We were really poor. I would see books in a friend’s house and in the library, but I didn’t have any money. I studied arts when I was 21 – two years before I left for Milan – and I would think, ‘Oh my god, the first time I make money I promise I will go buy books!’ I was so frustrated. At that time there was no culture. Not like now with the Internet. We didn’t have all that. In Rio, if you were studying you needed to have the object. My dream was to buy art books.

And that happened…

In my first year in Milan I started to have some money, so I bought my first book. It was on Picasso. I am not a really big fan of Picasso. I mean, I love him, but in art I really love Braque more. I don’t know why I bought it, probably because it was really obvious – the first book I buy about art, I buy Picasso! And one of my first jobs in Milan – this is before I met Domenico and Stefano and started working in fashion – was with the Brazilian Consulate. I was hired for four hours a day to clean and catalogue their library because it was so disorganized. For me it was a gift to be touching and working with books every day.

When you say you were in love with books, was it ‘books’ or was it the content and the art inside them?

I think in the beginning it was about how I could get my hands on culture. How I could touch the information because I wanted more tools and instruments for my life. But it was also a love for the object. Today, probably 30 percent of my books, the contents are not incredible, but the binding and the paper are so beautiful. The packaging and the object are so important to me. Often my job, my profession, has been related to that: I made books, I designed books and my relationship with these objects changed a lot. I started to understand about the papers, the materials, the volumes, everything. The books are not just about the contents or what is happening inside but everything else: the smell, the colour, the object.

‘Thirty percent of my books, the contents are not incredible; but the binding and the paper and the packaging and the object are so beautiful to me.’

When you were young you wanted books to have access to culture, but now your young employees can see everything they want…

I think how lucky my guys are who come here and have everything that I didn’t have, but the reality – the sad reality – is that I look and I never see anyone out of the 25 people working here, looking at the books! Maybe once every three weeks there is someone with a book! It’s the saddest thing because Google and the Internet killed all that.

But they are designing for non-print, digital products.

Yes, I can understand because in the last years my clients no longer want a catalogue so much. We do it for Miu Miu. I think Miuccia Prada is the only client who still likes a catalogue and thank god for her. It’s weird in a way how I still have my passion for books. My passion is huge, it’s such a contradiction with the time. I thought that maybe over the years my passion would slow and that I would not buy so many books, but no way, it’s the opposite! I respect the times, I love the Internet, but books are my love, my passion, my life.

Do you also have books at home that aren’t in this studio library?

A lot! A lot! In my house in New York I have the books I really love. More art books and fewer working books, fewer fashion books. In São Paulo I have more on Brazilian culture. Of course I have books in my house; I need them there!

And is it important for you that other people in your life and your work know you have a lot of books?

It’s for me and not for anybody else; it is not something I am doing to showcase. I am not like, ‘Come and see my collection of books!’

How do you respond to other people with great books? Do you warm to people who you know also buy lots of books and love books?

Yes, when I realize people have this love we exchange information, of course. I went to my friend’s house and he had a billion beautiful books and I realized right there, I don’t have this or that and it is so weird because in the arts and fashion I thought I had everything. I have bought a million books, and duplicates!

How many books do you have? Not a million, surely!

I don’t know, 4,000 maybe, 6,000? I prefer not to know. I have some amazing books, some very important books and some very cheap books that I am very attached to. It’s not just about expensive or rare books, but also books that relay some message to me. It is about love.

Did someone design your office space or did you design it?

I drew my first idea but my friend, who is a young Brazilian architect, he said I needed help. I needed a space where I could put all my books together. The most important thing is the library.

‘Books are the most important thing in my life. I’m starting work on a foundation in Brazil for the poor in Rio; I’ll donate all my books to that when I die.’

The books are the centre of everything.

The books are the most important thing in my life. I am starting work on a foundation in Brazil for the poor in Rio and I am going to donate all my books to that when I die.

What was the thinking behind that?

Well, I don’t have any kids and I don’t have anyone in my family who cares about these books. I had to think what I would do with them all. So this is my dream. It is what I didn’t have when I lived in Brazil. I didn’t have a place where I could look at real books with incredible collections of images. I think it’s good to do something in Brazil because I was born there and I am completely crazy for my country. I am crazy for my city. So I really want to create an opportunity for the people who don’t have the money, so they can touch them and see these collections in a free way. It is not easy because doing a foundation is so complicated. So what I am doing is starting to think about how we do this. I’m not going to start giving my books away for, well, another 20 years! I hope I live a little more!

You’ve got time to plan it, but it gives you a focus to what you are doing. I like the fact there is a result, that you have an ending.

It’s very important. At the same time I don’t want to give the problem to friends or somebody in my family because, can you imagine if something happens to me? [Knocks on wood.] Where are you going to put all this? I don’t want my books staying here; I want them to go to Brazil, you know. Years ago I decided to donate all my books when I reached 65. And then my friend asked me, ‘Giovanni, in 15 years are you sure you will be able to live without your books?’ I need to believe I can exist without my books; I need to do some therapy! In my heart I would not like to live without my books. But on the other side I don’t want to do this when I am dead! I would like to see my foundation opened in my lifetime. I would like to go there and see people look at my books.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Hans Ulrich Obrist likes a good conversation. (The Interview Project, his series of marathon discussions with key figures on the global cultural scene, is now 2,000-hours long.) But if there is one thing that Obrist likes more than the spoken, it is the printed. An inveterate collector of books since his childhood, the globetrotting curator-writer-publisher now has three archives of books in three different countries, to which he adds a book a day. For Obrist, paper not only has a future, in many ways, it is the future.

David Owen: When did you start acquiring and collecting books?

Hans Ulrich Obrist: I had these very strange feelings already as a teenager that I wanted to do books. It was always my kind of dream to be able to do books, to write books, to edit books. So from the very beginning the acquiring of books was some form of non-systematic collecting.

I understand. It isn’t about being a collector…

I believe very much in this idea that when we use a car, we don’t necessarily have to own it; the same is true for houses, you don’t have to own a house. I’ve always been rather nomadic, so in different cities I rent apartments. But with the books, I do like to own them. I don’t like to borrow them because I like to carry them when I travel. I want to use them, I want to annotate them, and sometimes I need to keep them because of those annotations and the Post-it notes I stick into them. I need to own the books so I can do what I want with them.

It sounds like you aren’t precious.

It is not fetishistic, and it’s not iconoclastic either. Pierre Klossowski was my great friend and he gave me a book many years ago. He dedicated it, ‘Ad Usum’ or ‘to be used’ – because books are to be used. This beautiful Latin sentence was always my motto in a way for the archives.

And so the book buying fuelled your career and that in turn fuelled the book buying?

Very early on when I was a university student I started working as a curator in parallel to my studies. I did my Kitchen Show when I was 23 and then I started to work with Kasper Koenig. I was curating this big painting show with Kasper and he insisted that I got the same fee as him. So suddenly I could buy books. I had a job for the first time that lasted for more than a week! Every single penny I earned went into books. So soon the apartment I shared was completely jam-packed with books.

‘I’ve got approximately 30,000 books in Berlin, about 5,000 in London, and probably another 2,000 at my mother’s house in Switzerland.’

I know you have always had more books than space. How do you manage that?

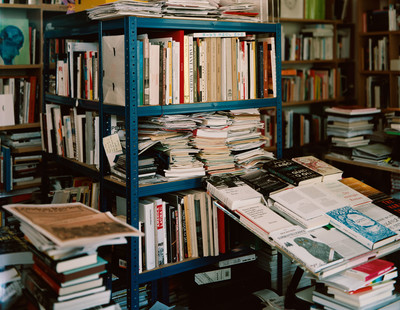

I was very inspired by Kasper and he had this wonderful system of order and disorder. I also went to see Alighiero Boetti as a teenager. Boetti was a great inspiration in terms of classification. He made this beautiful book about the 1,000 longest rivers in the world. You can’t ever really measure a river 100 percent because it meanders, so then you follow one source and you establish an order, but that order implies again also a disorder. So in an interesting way it is order and disorder rolled together. I was kind of interested in this because I didn’t want there to be a system in my library where everything would be millimetre precise, yet I wanted to find things again. So I created this system of order and disorder. I took archive boxes and I would put every single document about an artist inside a box. So it was easy to find an artist’s box, but within the box there was kind of chaos. It was every invitation card, press releases and it was pre-Internet, with the fax machine permanently running in my apartment, so thousands of faxes, too. Little by little these boxes got stacked into gigantic piles. Box on top of box and sometimes they would collapse. It was a kind of architecture in the apartment.

How systematic are you at buying books?

Utterly, completely unsystematic. Some of my friends really are book collectors. They collect all the books by an artist and then they have to find, at huge expense, what they are missing. That is not my methodology. That is not part of what I do. It is more like being permanently inspired. I am driven by this curiosity, fuelled and driven by endless curiosity all the time. I buy books that I want to read all the time, but I also buy books because of their physical presence – some I just need to have. So there are different reasons as to why I buy books. It is always very spontaneous, but I do buy a book every day. I cannot survive if I do not buy a book every day. It’s very much a vital thing, like drinking coffee or breathing.

Perhaps out of necessity because you have so many books, your archive is not just reference and inspiration, but also the subject of your work…

I became a professor at the University of Lüneburg in 1994 and my first professorship was to solve the issue of archives. I invited the German artist Hans-Peter Feldmann, who is a great master of archives, to do the project with me. So with my students we got a room in Lüneburg, an attic room that the university didn’t use. Hans-Peter would always come and so we had this sort of Feldmann study centre with the archives. We called it Inter-Archive. It’s very interesting because there I was, 26 years old, teaching at this university and how pretentious would that be to suddenly attribute value to my archive? Hans-Peter Feldmann came up with the most wonderful ideas about how to classify books, like weighing my archive, describing the smell, so many different criteria. You can do it by colours and it creates a very beautiful system. Then order and disorder. When you do that in your library it suddenly creates very interesting conversations. Feldmann did many classifications, by weight, what they felt like, touch. My archive became a kind of experimental field.

‘It’s always spontaneous, but I must buy a book every day. I cannot survive if I don’t; it’s very much a vital thing, like drinking coffee or breathing.’

As you said, there are lots of ways of classifying and lots of ways of looking at a library, but people reading this will always want to hear a number. Do you know how many books you have?

There are probably 30,000 in Berlin. We’ve got about 5,000 in London, and there are probably about 2,000 in my mother’s home in Switzerland. These are the archives of my books, but then there are the archives of my work. I am very bad at archiving my own work because when one starts indexing one’s own work it is very suffocating. I always have to think about the next show and not look back. Serge Daney, the French film critic, wrote his mother and father a postcard every week from wherever he was, and I too started to travel a lot when I was young, so I started to send my parents every single article I published, every book which came out with contributions of mine, catalogues I edit, all of that, it all goes to my parents’ house. My mother always reads what I write so that keeps the connection.

It must be nice to feel like it is gone but not lost.

Yes, and a second copy of everything goes to Chicago, to the American artist Joseph Grigely, who decided to archive me early on in the 1990s. He thought it was funny for an artist to archive a curator because normally it is the other way around. So he asked me to send to Chicago a copy of every single thing I do. It fills maybe a FedEx box or so a month. So those are two more archives. And I am sure there are others that I forget.

Can you talk us through the construction of the archive?

When I was 23, 24, after the Kitchen Show I got a grant in Paris at the Fondation Cartier and I drove my very old Volvo to Paris; I’d jam-packed it with books – as many books as I could fit – and I went to Paris with this kind of transient library, on the move. So I was at the Fondation Cartier for three months and then from there I went to work with Kasper Koenig in Frankfurt. Then in 2000, I began to spend four or five days every week in Paris, but I would still travel every weekend. So that means we created the Paris archive, because we rented an apartment there, but with the old archives still in Lüneburg. Then in 2006 I came back to London to work, but the Paris archive was the newer one and my most important, because that was where I kept my interviews. I didn’t want to rely on the removals firm because the interview archives are so precious, so I put them into two gigantic suitcases and took the Eurostar to London.

The Paris archive had become the London archive, but then the bad news came: the University of Lüneburg had appointed a new dean and that new dean had basically asked McKinsey to make the university more efficient. As you can imagine one of the first things McKinsey asked was, ‘Why does some Swiss guy have 100m2 in the attic filled with books when he doesn’t even live in Lüneburg and only comes a few times a year?’ So they threw out my books and in 2006 I found myself with nowhere to put them. London has exorbitant rents so I could never rent 200m2 here for the 30,000 books. So then I needed to come up with a new plan and that triggered this idea to have a London archive for the Interview Project in my small apartment and then put the Lüneburg archive in Berlin because rent there was cheap at the time. So I rented a very big apartment there in 2006, and the books are still there. But they have never really been unpacked; they are still in these boxes. So it’s a kind of situation in waiting. It’s a place where I write because I accumulate books to stimulate my writing.

Rents in Berlin have gone up considerably so I recently began moving the archive to Brussels. It’s cheaper and also really convenient to visit on the train. Flying is harder to justify now – too polluting – so I take a lot of night trains, but it takes 15 hours to get to Berlin! Brussels is much easier. My archive has always been in-between and now it is an inter-archive, literally.

‘We thought radio would vanish when television was invented but the opposite happened – radio became more creative. The same is happening with books.’

Is it possible for you to do what you do without your books?

Art books always have played a role and they still do. I have friends who are collaborators and who are 10 years younger, so now in their 30s, and they still have an attachment to books. We started this 89+ project for which we talk to artists born in 1989 or later. We already have more than 6,000 people in that archive – designers, artists, architects, and so on – the first generation that grew up with the Internet. And what is interesting is that one of the first patterns we observed – because we wanted to detect patterns in that generation – is that poetry is what links them all. There is this new energy for poetry. It is amazing how many brilliant young poets there are on the social networks. Yet for that generation the book is still relevant. We see a great culture of fanzines in the 89+ generation, a lot of artists doing their own DIY publishing. These are all things where people are not even relying on formal publishing anymore.

I wonder how much books have been a convenient medium and that convenience is shifting?

You can see it also with hardbacks and paperbacks. I read a lot of stuff on the Kindle and my iPad, and I wouldn’t necessarily buy a paperback any more, but I buy far, far more hardback books. So I think in a way what is interesting is that there are certain types of books I don’t have anymore: I certainly wouldn’t have a telephone book; I have it online. I don’t have an A-Z anymore; I have Google Maps now. Yet I don’t buy fewer books than I used to buy and I think that idea of the book’s reinvention is really interesting. We thought radio would disappear when television was invented, but the opposite happened and radio became more creative than ever before. So I think in a way the same thing is happening with the book. I read this great piece the other day in Scientific American that suggests reading on paper still has great advantages, in spite of e-books and tablets, and those advantages are not going to disappear. The brain interprets words differently on paper to screens. We often think of reading as a cerebral activity concerned with the abstract, with thoughts and ideas, themes, metaphors, motifs. As far as our brains are concerned, however, text is tangible. It is part of the physical world we inhabit, the brain essentially regards letters as physical objects because it does not really have another way of understanding them. So it is fascinating that from this new scientific point of view, books will not disappear, which is great. Paper books have a more obvious topography than books on the screen. A reader can focus on a single page of paper without losing sight of the whole text; one can see where the book begins and ends and one can even feel the thickness of the pages. Turning the pages of a book is like leaving one footprint after another on the trail, there is a record of how far one has travelled. All these things make reading a book more navigable, but also it creates a mental map.

Mental map is great way of putting it.

So what I did this weekend: I looked at hundreds and hundreds of books at home because we are working on a topic of resistancies and transformation, and I just went through all my books and made towers out of them. I think that very physical thing has to do with memory, and the books prompted lots of ideas. So it is like a mental map and in a way there is so much information on my laptop and my computer, it’s like an infolded monster, it folds in so much information. But with a book, you have your four corners, your eight corners; it is simplified, that is also true for the book as an object. It is a very simple frame and that simplification allows you to build up a different kind of complexity, plus I can get lost in this enormous mass of information. So I think for my thinking and my writing it is an essential thing. The research happens both ways: there is analogue research and digital research, but I would hate to give up one for the other. I would miss something; I think we need both. I never understood why you would give up radio in the age of television.

What are you going to do with it all? Do you already have a plan?

No, I was happy with the books at Lüneburg because they were used by the students. I don’t want this to be a dead archive; I want it to be a living archive. We did the Swiss Pavilion that I curated for the Venice Biennale in 2014 and we tried to manifest a statement about living archives by revisiting two great visionaries, Lucius Burckhardt and Cedric Price, through their archives. You would walk into an empty pavilion and then a student would come up to you with a trolley of papers and engage you in a conversation. It was live; it was performed. After Feldmann in Lüneburg and then Venice, I would love to continue on this track. Archives always get brought to you on a trolley and so this trolley became our display feature. So we are back to the idea of the archive on the move. In a way I would love to invent an archive that functions like this pavilion, but with a base where new people can give it new meaning, and that is what we are going to do in Brussels. For me the archives are like Russian dolls, there is an archive within an archive within an archive. For example, there is another archive between here and Berlin, which is all the signed books, what artists, poets, architects could sign or write in a book. What one writes in a book I think is always very interesting. It gives me ideas for my own book signings because I never know what to write and some people have great ideas. So I have a whole archive of signed books. And that is the beauty of handwriting and that signed book archive was the trigger for my handwriting project on Instagram. I now have thousands of Post-its – and that of course is another sort of archive.

How old were you when you started acquiring books?

I think it all started when I was a teenager in Switzerland, in my room. My childhood room became more crowded with books. It was initially literature – like Robert Walser who became my childhood obsession – so there was a lot of literature books and then when I was about 13 I discovered Giacometti. I saw these long thin figures and I became pretty obsessed and I started to buy more and more art books.

And you’ve never stopped?

No! On Saturday I saw this wonderful book shop and suddenly thought, Wow I need to go there, and I bought five new books. I hadn’t even planned to buy books, but it’s always like a flânerie.

André Balazs

André Balazs is both a public figure and a private man. And the success of his hotels is based on the similar offers of privacy when desired and public exposure when required. His group grew from the purchase of the Chateau Marmont in 1990 and now includes The Mercer, the Standard hotels and, most recently, The Chiltern Firehouse in London. And while Balazs has been successful on a grand scale, as anyone who has worked with him or even stayed at one of his hotels will know, it is a success built on an extreme attention to detail. For every hotel, from city to neighbourhood, building to room, chair to the joinery, Balazs has a hand in decisions about them all. In his office and his home, he goes even further into the details, pointing to a specific page marked up in one of the hundreds of books in his impressive design reference library. From an early age he used books to fuel his ambitions, and diaries to record his progress. Now, with many friends in the media and creative industries, Balazs has devoted a section of his library to the books they publish. It is a complete circle: books as impetus and end result.

David Owen: I am going to say very little. You tell me about you and books.

André Balazs: First I should explain that I use books very interactively. I mark them up; I tag them; I use them for reference. I started collecting my books and using them as a form of diary in and around eighth grade. I would underline books heavily, date them and annotate them. I would date when I started them and when I completed them. They were meant to be physical objects that were destined to be kept as part of my intellectual journey through life. I always thought of it that way.

Were you always using books to advance your knowledge and yourself?

Well, it depends on which books. I live with books both at home and in the office. There are four main categories of books in my library. Very early on I was interested in philosophy. I never read fiction. I always hoped my life would be more interesting than fiction. There were a few writers who I admired for their participatory nature: Tom Wolfe, Norman Mailer and Gore Vidal, who was an early hero of mine. They were people who were not just observers but also participated in the rough and tumble of life and I felt that was compelling. So my early readings were philosophy and about people like that. I very much saw these as journals of a life well lived, fully lived and documented, and that is what I started collecting. Well, not collecting, but I found myself keeping them and storing them next to my own diaries up on shelves where I grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

So that’s one category. What are the others?

When I got into the business I am in now I started to look at design books particularly. I found certain things just require tremendous repetition to get right. It’s an old adage that there is nothing harder to design than a chair because, basically, there have been a million designs before, so to get it just right is tremendously difficult. To have access to the original attempts at this kind of stuff was very interesting and I started finding the original sources in old books. And I started to really get into these photographs from the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, and buying collections of everything from catalogues and magazines to unique one-of-a-kind books. At one time, early on, I wanted to be a dancer. I was always very interested in it. My mother was a gym mistress and dancer. I was very interested in early dance groups, pre-dating Martha Graham1, like the Denishawn School of Dancing. Also the early naturist, nudist movement – I became very, very interested in that. Post-world wars in Europe, there was this tremendous emphasis on good health. And fresh air, clean living and exercise was all part of it. And with that came, in Germany and Scandinavia, this whole naturist movement, which is accompanied by group exercise, like archery or dancing. I became a very, very big aficionado of this naturist movement combined with modern dance and images of it, because I found them very beautiful and very modern. Unlike those kind of more overtly erotic pictures from the 1920s in Paris and the Weimar Republic, these were pictures based on body types that in today’s language you would view as the ultimate in good health. Not overbuilt, not anorexic, but healthy bodies. It’s not sexual at all: it bears a closer resemblance to dance and physical health. I am a big fan of Pilates and I just read the history of Joseph Pilate and the aesthetic of the dance and movement that came out of that, which then got picked up by the Denishawn School. That spoke to me very deeply because they were located across the street from the Chateau Marmont. So, for example, when I bought the Chateau about 25 years ago, we actually started running ads just to give atmosphere to what I hoped the Chateau would become – which is this very free, open-minded, healthy environment.

‘I realized that one out of every four people I know has published at least one book. So I have a collection of them; good or bad, it doesn’t matter.’

That’s two categories; what’s the next?

And then the last category I have simply because of the kind of friends I keep and enjoy. I just started realizing that probably one out of every four people I know has published at least one book. So I have a section of books that are by my friends, good or bad, it doesn’t matter; I have hundreds of books by people I consider good friends. I had a minor accident that was emotionally very traumatic for me when Katie Ford and I first got married. I had a very extensive post-college library and when we were moving into a loft in SoHo we put our belongings in her parents’ house in Connecticut. They had a fire and the tragedy for me was that many, many books I had perished, including all my personal journals. I think the subsequent interest in collecting friends’ books was a direct evolution of that. I found myself early on in the words of others and in the worlds of others. Part of my life continued on in the writings and thoughts of my friends; it just happens that they are incredibly prolific.

To me, having books and a library is all part of the richness of documenting your own experience, bringing you closer to those things that inform you. This is all very eclectic; I probably have as many political biographies as I do design books. But about 10 years ago, I decided I wanted, for professional and other reasons, to have design and photo-history books. I don’t mean regurgitations of texts, I mean original stuff. I decided that I was going to try and build one of the better design libraries.

I like how closely the library influences and then reflects your life and work.

I grew up in Sweden; my parents are from Hungary, but in 1943 they moved to Sweden and lived there for 16 years or so. They lived in a very modern house just when all of the most modern Scandinavian work was coming out after the war. When they moved to Cambridge, we moved into a house that was radically modern. And a few years ago I was up there and I just bought a book published in 1963 on modern Scandinavian design in a used bookstore. I took it home and I was so proud of it. And the next week I went to see my mother who was still living in the house I had grown up in. I was browsing through the library there and I found exactly the same book that my father had bought in 1963! So I suddenly had two books side by side, one I bought years later and the other that he had bought the year it came out, complete with the markings on the pages of things that he admired. So I now have two identical books, one with my own tabs and one with his from 1963.

2manydjs

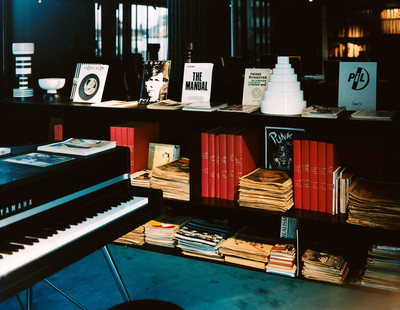

You’ve heard (and heard of) Soulwax and 2manydjs. You are probably less familiar with the names David and Stephen Dewaele, the brothers behind the label-band-DJ duo. And you’re probably completely unaware that the Dewaeles are dedicated and voracious book collectors. From their bases in Ghent and London, and everywhere from Mexico to Tokyo, they are constantly travelling, DJing by night, book-hunting by day. The brothers were brought up in a musical household (their father was a well-known radio DJ in Belgium) and formed Soulwax in 1995 when Stephen was 25 and David 20. Today their world of music, books, magazines, documentaries, films and art has become a self-sustaining culture machine fuelling the creation of new ideas and work. We met up in London where they stock their books on everything but music – those are back in Ghent, with their 55,000 vinyls – to discuss what drives their passion for the printed page.

David Owen: Tell me what you buy.

David Dewaele: I guess maybe everything. The obvious ones are books on Fiorucci, Woody Allen, anything counterculture, 1960s, 1970s, cybernetics, Archigram, Sottsass, Memphis; everything that’s airbrush, photography… but obviously photography is such a broad label it can mean anything… It’s books about everything.

Stephen Dewaele: But in reality it’s not actually everything…

David: When we go into a bookshop we don’t necessarily gravitate towards gardening or, you know, psychology books.

And why are you buying almost everything?

David: When it comes to music books it is very clear why we buy them. It is easy to trace back. We grew up in a house where there were always promotional copies and pictures and press kits and all that stuff lying around.

Stephen: That’s where we come from.

David: I mean, I don’t want to get too Freudian here, but it might be reaching back to where we came from. It doesn’t explain why we buy Archigram books though.

Stephen: I think that as kids we saw new record sleeves all over the place and our mum and dad were buying the magazine Hara Kiri all the time. That was normal. So we grew up amid this imagery that’s evocative and sometimes takes you to another world. When you are a little boy, you get lost in that.

David: It still doesn’t necessarily explain why we have got a big collection of typewriter-art books!

Stephen: Because they’re amazing!

David: There are a lot of things that we buy where there is no direct vehicle for them in our work, but we are still as eager to buy them or get them.

‘We buy books on everything: Fiorucci, Woody Allen, anything counterculture, 1960s, 1970s, cybernetics, Archigram, Sottsass, Memphis…’

Like books on Concorde.

David: Yes!

Do you both approach your book collecting the same way?

Stephen: In the beginning if both of us went to the same place separately, we would both come back with the same records or the same books or the same trainers, the same. But I think we’ve become experts in trying to go even deeper and get to the next level.

David: With music we have even come to the point, Steph and I, where we go to record stores and buy things we don’t like yet but that we think we might like in 10 years!

That is crazy. Do you do that with books, too?

David: The one thing I would say is that we’re not completists. If we’ve got issue five and seven, we do not need to get issue six.

With music it is clear: you buy records and you are also making music. But with books, you are not making books or magazines…

Stephen: When you look at our recording studio you can see we are using really old mixing desks and a lot of materials that have a character and a sound that we like. It is a medium. We have never made or published a book, we have never done any of that, but it is definitely a medium that really interests us. You start getting into how something is printed and there is a whole technical layer that we are really, really interested in. The same interests we have in music, the same thing with us buying 16mm cameras and finding out how they work. There is also an element of experimentation. Maybe searching for something.

Tell me about the spaces you have. You built your studio in Ghent around your record collection. Do you have similar plans for the books?

Stephen: We want to do something. Storing books like this… putting the spines towards you and classifying them like this is annoying. We have so many good things and the reason we have them is to be inspired by them. In the studio we are trying to find a way that we can display them, sort of like in a shop. So you can change around the covers that are on display. Otherwise with records and books, you store them in a beautiful way and you always see the spines, but you never see the cover art and you kind of lose track of them a little bit. We want to have a shelf where we can just put up new stuff every week.

Displaying the covers is a means of sharing them and the ideas. Is sharing what you’ve found a motivation?

Stephen: I think that a lot of the friendships with people who are really important in our lives have come through shared taste and enthusiasm. Fergus [Purcell, aka Fergadelic] is a really good example. He is someone who gets it on every front: music, film, photography…

‘In Tokyo, you go three flights up and there’s a guy sitting there: he’s got every book you ever dreamed of, or didn’t know that you were dreaming of yet.’

But these days kids do all that connecting via social-media profiles…

David: Yes, but on Pinterest or Instagram you look at the online collection of what someone is saying they are into, and it’s like, ‘Wow, cool’, and then you click on it and you actually know who that person is in real life, and it is like, ‘No way is that the same person!’ There’s no connection. It’s only because that person has seen that someone else has liked it that they think that’s what they need to show, to come across as more intelligent. And it doesn’t only apply to records or books, now it’s just part of life. People are living a second life, one that’s an extrapolation of what they live in real life. We are dinosaurs because we don’t do any of that. We are [gesturing to all the books] real life!

Kids now might not have the compulsion to buy the things they like.

Stephen: But why would they? They don’t even have the money. They wouldn’t think about it. There was a long time when we couldn’t afford to buy a £100 record or book because that was a lot of money. And we would gravitate to whatever was free or whatever was cheap or what you could steal. I do think that if I was growing up now that it would be an amazing time. We collect these things physically but young kids are looking through it all online in a digital way. I do feel that it does influence them. I think in music and in printing there are artisanal ways of creating these objects that we might think we would lose in the digital world, but then on the other hand you see these kids obsessively going back to that record or that book or that espresso machine.

Online or real world it may well be the same obsession.

Stephen: For me a really amazing book fair is like a holiday. There is nothing cooler for me than going there and coming out with unexpected things.

It is like going to Japan.

Stephen: I dream about Japan…

David: We call it Treasure Island because there is always something and it’s usually not in the place you expect it. You walk two blocks and there’s a new shop that wasn’t there the last time. You go three flights up and there’s a guy sitting there and he’s got everything you ever dreamed of or didn’t know that you were dreaming of yet.

Stephen: Japan is Treasure Island, like Amazon for cool people…

Grace Coddington

Pre-Internet, pre-digital and pre-eminent. Grace Coddington has been a Vogue fashion editor for three decades and thanks in large part to The September Issue, is now one of the industry’s most recognizable figures. Grace’s entire working life has been in print – as a model, as an editor, as a voracious researcher and book buyer. As the world becomes ever more digital, Grace retains her love of objects. The Manhattan apartment she shares with her partner Didier Malige and their cats Bart and Blanket is packed full of books, while on the shelves stuffed toys, ornaments and mementos fill any gaps between the books. The walls are filled with framed photographs; look in any direction and you see back in time to classic shoots by Bruce Weber and Steven Klein. Yet, for Grace, these books and photographs are perhaps the future, too, maybe the spark for the next shoot or issue. This organized chaos is her inspiration, her frame of references; the work itself is all around her. Her ideas, her friendships and her books are all interwoven. It is a network, if you like. The apartment as a model of the creative working mind.

David Owen: You have the books piled up in what I consider quite a Parisian fashion, lying flat rather than spine out.

Grace Coddington: I moved in one day. I had all the interns from Vogue help me and they just opened up the boxes and shoved them on the shelf. It is not the most convenient way to find things and we’ve got a million books since then and they don’t fit in. It’s not just me – a very big percentage belong to my boyfriend. He runs out and buys books every single goddamn day and he doesn’t just buy one copy; if he sees a book he likes he buys six. So we have so many books and hundreds of the same book and that’s why every little corner is full. And then it’s the same again in the country.

Immediately, I can see books that relate to your work. Are these books a reflection of your career?

Yes, they are. One has a lot of inspirations and you know, for want of a better example, maybe you are doing something that’s inspired by a Picasso exhibition and so you might go out and buy six Picasso books because you know you want you see the whole breadth of it.

Other people might have a book collection that is very aspirational with travel books of places that they would love to go to…

I don’t have that.

‘I had all the interns at Vogue help me move in. They just opened up all the boxes and shoved the books on the shelves. It’s not ideal to find things.’

Or objects they would love to have…

I don’t have that either. They are all somehow related to a shoot I’ve been doing or am going to do. Obviously, there are others I have because they are by a friend of mine, a photographer, or I’ve contributed to the books in some way. Joe Szabo just had a book come out on the Rolling Stones and he asked me to write the foreword, so I have that and that’s not really related to anything I’m doing. But his first books – Teenage and Almost Grown – I found very inspiring fashion-wise.

There are also funny random books where you might say what the hell is that doing in there, but it will be something to do with a shoot. It’s like a tree with branches and then they all lead to the story that you are trying to tell.

Many people who read this won’t work with books and I think they will find it interesting to try and understand that.

There are lots of people who go out and copy pictures. I am very opposed to that, particularly in the fashion world. Helmut Newton is endlessly copied; Guy Bourdin is endlessly copied. And sometimes the pictures people are copying I actually got to work on! I think it’s ironic. There’ll be an inspiration board and there will be all these pictures and I see them setting off and putting people in the same positions and I say, ‘You can’t do that, I was there on the original shoot!’ I don’t need to do it again and actually you can’t better the original photograph. Reference pictures are my pet peeve.

Photographers say, ‘Where are your reference pictures?’ and I say, ‘Oh, you know, just go and read the story of Alice in Wonderland’. I don’t want to see how other people interpreted it; I want it coming fresh from you and the story. But now people rely on reference pictures because nobody has any time and everybody shoots back to back because of digital. They think they can do it faster and actually it takes the same amount of time, they just don’t print it in the bath at night. They just move onto the next story and they don’t actually have time to think anymore. I want them to go through the process. Nobody goes through the process anymore.

Tell me about the process and how it works with books. For example, the Bruce Weber British Vogue story ‘Under Weston Skies’.

Bruce gave me all the Edward Weston Daybooks to read. I’m not a great reader so I must say I didn’t actually read them all, but I looked at the pictures! And then we went out and had ‘an Edward Weston day in America’; that’s what it was. The idea was inspired by that – but no individual picture was directly inspired by another picture, and that is why it’s so fresh. Bruce brought me to American culture and I was completely ignorant about it. He taught me so much as a whole, a fashion photographer coming from a different angle. All these references: Georgia O’Keeffe and Andrew Wyeth, and then we did Weston.

And Bruce is a big book buyer…

Oh my god! He’s another one who buys 10 of everything and he gives you a hundred books for Christmas. That’s another place that these books have come from. He goes shopping with an entourage. He does it all through the year. He drags the books back to his loft and has them sorted into ‘this is what Grace would like’ or ‘this is for friends’. And I guess the Christmas present pile keeps growing. It’s amazing. I completely took on his love of photographs on the wall. That is where my collecting photographs comes from. Also the books and vintage buying and the whole layout of a place. Yeah, I completely ripped him off! I used to think I was kind of minimal, but I’m not. There are too many things that I love, that I want to have.

‘When I did my memoir they said, We’re going to do an e-book, and I said, Oh please don’t! But they did. Well, I think so. I haven’t seen it. I don’t care.’

There is a possibility that future generations will just be less bothered about books and possessions…

I don’t think people are so focused on books anymore. When I did my memoir and they said, ‘Oh, we’re going to be doing an e-book’, I said, ‘Oh please don’t’. But they did. Well, I think they did an e-book; I haven’t seen it. I don’t care. I just wanted to make it as beautiful as possible – and they just wanted to make it as convenient as possible.

At least at Vogue you work in print.

It’s a whole turnaround now at the magazine: the digital side is so much more important. It just is. We’re old has-beens and they are plodding on and they need us for the moment because they haven’t quite figured out – well they have figured out the digital thing, but not so that it makes money. The whole digital thing only has to take your attention for one second and then it doesn’t matter and it’s gone, and I think that magazines last a little longer. Not as long as books, but they do last a little bit longer and people do pass them on.

They survive, yes. Like you have books that are signed or full of Post-it notes.

Yes and that’s fabulous. Imagine coming across a book with little things jotted in the margin by some fabulous writer. I don’t know, it just adds another layer to it. I have the most incredible handmade Bruce book from the Weston story.

That’s what I was going to ask to see…

I tell you, it’s amazing. It’s in a paper bag and falling to pieces now. The National Portrait Gallery has asked to borrow it. Bruce made one book for me and one for himself. That is what he used to do with a lot of shoots in those days. And they are fabulous, but they are falling to pieces. I treasure it but I don’t know what to do with it to preserve it. The one he did for himself, the same thing has happened. He does put them together with this black sticky tape and then it dries up and then it curls and falls off.

It is amazing.

It’s priceless and if there was a fire that would be the first thing I would save.

Kim Jones

There are many minimal executive offices lining the corridors of Louis Vuitton’s headquarters in Paris, but Kim Jones’ is not one of them. His office could best be described as busy. There are people ducking in and out and asking questions, but there is also stuff: books, photographs, auction catalogues, keepsakes, African and Asian art and craft, vintage clothing, scrapbooks, gifts and gift notes. To many people these might just be inanimate objects, but to Jones this is where the action is. A copy of Antonio’s Girls by Antonio Lopez, dedicated by Lopez to Studio 54 impresario Steve Rubell, is a source of creative energy. And that copy is only one of three, all signed to different people, that he has to hand. He likes it to be personal and he likes it to be real. So he has a complete look from Vivienne Westwood’s ‘Pirates’ collection; a full run of WET magazine; the actual desk from Virginia Woolf’s study. Jones holds a great respect for the creative lives of others. In acquiring something of those lives and keeping it close, he channels that spirit and talent into his own work.

David Owen: Tell me about your books. What do you have here?

Kim Jones: There isn’t one specific genre. It’s not just fashion. I like facts. I’m not very good at reading fiction I have to say, but I love a biography. I love any sort of photo book of an era or a time. I look for an insight into people’s lives, not just their art. Culturally I’m interested in so many different things.

You are extremely thorough in your buying…

I am definitely a completist. If I like something I want to get every single thing of it. Whether it’s Bloomsbury or Omega or modern things, just things I love. They have all become part of my life. You could take me out this room and still see who I am through the books or clothing or the art I have. I can also picture other people through things and that is why I love those auction catalogues [such as the Yves Saint Laurent or Versace house sales] where you can see interiors and ideas and how people put things together.

‘I’m definitely a completist. If I like something I have to get every single thing of it, whether it’s The Bloomsbury Set, Omega, or modern things I love.’

And can you see how it ends up in your work in terms of the collections? When you travel somewhere in the world, the culture or craft are shown in designs. But when you go somewhere through books, how does that work?

For me Louis Vuitton is a travel house and I base every collection around something related to travel or a destination, because it is what our customers understand. They like the storytelling and understand that. There have been pivotal books for me. Leonard Freed’s Black in White America was something I used to drag in front of Louise Wilson when I was at Saint Martins. There is a guy in the book leaning against a wall with the perfectly cut chino. It was just me, her and a pattern cutter and because the guy in the photo is in such an awkward shape, we were like, ‘How the fuck are we going to do this?’ I was just screaming and shouting and then laughing when we finally got to the point. Jackie Nickerson’s book Farm was something I picked up and got obsessed about: how these people had no money and styled themselves. The Kim Jones 2007 Spring-Summer collection was based on it. Now I work with Jackie and she does all our pre-collection look books. She is such an amazing woman. She is out there obsessing about the same details. We might both be behind the camera and she’ll be like, ‘Oh, that’s a bit weird, shouldn’t it be like that?’ She has that sixth sense.

And there are periods of history that you love…

There are whole subjects. Studio 54 was such a massive thing. This place where everyone went. So to get all the Steve Rubell books and ephemera [at a 2013 sale of Rubell memorabilia] was amazing. Just pulling things together, they tell a story of a time that is interesting. You can sort of create an impression of it.

Are you constantly interested in finding new subjects?

My eyes are never shut, that is one thing I can say. When I walk down the street, compared to someone else, it’s totally different. Everyone is like, ‘How do you see that? What made you look at that?’ It’s probably down to growing up somewhere like I did. I was living in Africa for quite a long time when I was a kid. A lot of our time was spent spotting animals in the wild and, you know, to see a leopard in tall grass is impossible. We would be on these trips in a car for nine hours, so you sort of focus on stuff and look at things, so that was definitely one of the founding influences.

It can’t just be people in fashion like you who have this obsession with looking…

A lot of my friends are DJs and they travel the world. They are in a city that they don’t know for two days, so they’ll go and explore it. And anyone who has half a brain cell who’s got an interest in the world and a passion for meeting people and seeing new things will then get interested in other stuff. And then there is someone like Michael Costiff, for example. He has the eye of the world that he’s seen, whether it’s Burkina Faso or Brazil to the carnival. I just think it’s those people who are visually aware or who understand the importance of culture. It’s a way of thinking.

‘I will multiple purchase a book that I really love. I’ve given copies of that Hiroshi Seditionaries book to people like Kanye.’

It is a way of thinking that may be changing…

One thing I say when I talk at Saint Martins is that it’s fine to look at things on the Internet, but then you need to go and find it for real. Go and find that book and turn the pages and see what is on the other side of that page. Because if you like that picture in that shoot, then the chances are you will like the picture on the other side and that might be something less obvious, so go and think about it.

You give out a lot of books as well as advice.

Quite often I will see something I’ve already got and I will multiple purchase if it’s a book that I really love. That Hiroshi book [Hiroshi Fujiwara and Jun Takahashi’s Seditionaries clothing book] for example, I gave [model] Matt Williams one; I’ve given Kanye one; I think Marc [Jacobs] just got one.

And do you share much with other designers?

If you know someone is really into something. Like I know that Stefano Pilati loves Kansai Yamamoto. We were in Japan together and found someone to introduce them. It is like building bridges, you know. I love Stefano’s work and I think he is amazing as a person. Those sorts of things, where he was also like, ‘Oh, you’ve got to go and see this supplier…’ That give and take in fashion is kind of rare now because it’s all about numbers and figures and stuff. But I think there is a lot more to give in that sort of way because I think if things are good then you should celebrate and enjoy them.

I think you enjoy these things perhaps more than anyone we know. You really love finding and buying things.

I sometimes joke when friends go to museums, ‘Oh, I don’t want to go that museum because you can’t buy the things and it gets annoying.’ I went to a Native American museum once and I said, ‘Wow, those slippers are amazing’, and the guy said, ‘Well they’re for sale if you want them!’ That’s my kind of museum!