When will pre-collections shrug off their persistent, insistent prefix?

By Alexander Fury

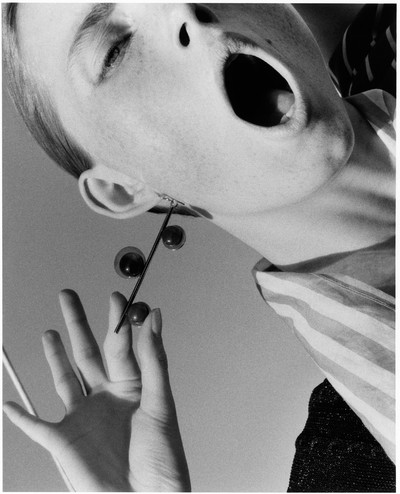

Photographs by Jamie Hawkesworth

Styling by Marie-Amélie Sauvé

When will pre-collections shrug off their persistent, insistent prefix?

When will pre-collections shrug off their persistent, insistent prefix?

Pre-, simply defined, means before – in time, place, order, degree or importance. The last word is the main issue: pre-collections are perceived not simply as before, but lesser. Less important, less worked. When, in conversation with Louis Vuitton’s CEO Michael Burke, I referred to them as ‘interim’, he shot me straight down: ‘They’ve become the major collections; the major collections have become interim. Because they’re very timely. Whereas cruise takes you from November all the way through to June. It hangs there that long. It’s actually who you are.’

Which is an interesting concept coming from someone who knows. Pre-collections – the inbetweener seasons, shown across a few drawn-out weeks in December and January, and then again from May to July, have soared in importance, and prominence. Phoebe Philo’s Céline, arguably the single most influential fashion brand of the past half-decade, has already dropped the pre-. It carves its clothing, internally, into four seasons: Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter. How long before everyone else follows suit? (And they so often do, with so many of their clothes.)

‘The season has grown in importance as European designers gain strength in this country and require new merchandise to fill their shops and departments between fall and spring,’ Bernadine Morris wrote in the New York Times back in June, discussing the contemporary fashion wonderland of the pre-collection. ‘In recent years they have all added collections they generally call “cruise” for American stores. They also find that these collections are gaining ground in Europe.’

When I say June, I actually mean June 1989. Yet it could have been written yesterday. We think of the pre-collection as a phenomenon of fashion in the here and now, but they’ve been around for years. Formerly presented by scrabbled-together showroom presentations and rudimentary racks of garments only shown to buyers, journalists were blinkered to pre-collections – by both themselves, and frequently the designers. They were begged, like Dorothy Gale in The Wizard of Oz, to pay no attention to the clothes behind the curtain, that may dispel the myth of the Great and Powerful Designer.

Only, pre-collections always made the money. They still do. Brands from Proenza Schouler to Prada have told me their ranges account for 60-80 percent of overall turnover. Those figures cannot be ignored, which the brands certainly aren’t doing. The triumvirate of French fashion behemoths – Louis Vuitton, Dior, and Chanel – are shipping guests across the world to experience theirs. ‘Experiential’ is the word most frequently tossed about, by people like Burke and Sidney Toledano, his counterpart CEO at Dior, to describe the importance of taking the fashion press on a voyage to express the ideas behind these collections. ‘You have basically three days to tell your story,’ states Burke. ‘As opposed to 15 minutes.’ That explains the lure of the pre-collection show: brands can monopolize the time of some of the world’s most influential press, pulling them into another world, a world of a brand’s own creation. That’s why the French trio was joined this June by Gucci, the multi-billion-dollar jewel in the Kering crown, which staged its first ever pre-collection show, in New York.

Alessandro Michele, Gucci’s freshly appointed creative director, said his collection, and that show, was about ‘the girl on the street’. But really, these clothes are about anything but her. That’s what all those trips express – it is about living the lifestyle of the cosseted clients who will actually be buying the clothes, the ones you often see at said shows, out in force in their natural habitat and dressed to the nines. They’re the frequently assumed fictional one-percenters – except they’re real (at least, parts of them still are). I’ve shared boats with them in Dubai and New York; I’ve watched them take seats in the blazing sunshine of Monaco and Palm Springs.

Pre-collections aren’t about me – me being the fashion critic.

They’re all about them. They were founded on the needs of those women, established with the sole aim of pleasing them. More specifically, they were born in the holidaying wardrobes of women with the wherewithal to chase the sun in the winter months. Sunning themselves while the rest of the northern hemisphere shivered in triple-layered cashmere, they demanded something unseasonably light. Hence the names given to the pre-collections shown in May and June, which drop in stores around November: cruise and resort, because you do the former to get to the latter in these easy, breezy clothes. Sometimes designers have gotten trapped in that mindset – the ruse that cruise demands fashion straight off the Good Ship Lollipop. Of course, that’s rubbish, as were many of the clothes.

Pre-collections are no longer an afterthought, but a precursor. They are the main event of the fashion calender, both geographically and ideologically.

So why are pre-collections – which have existed in some form since the 1970s, and have been a core of fashion retailing since the 1980s – only now moving into the limelight and being given their creative dues? There are multiple reasons, and in microcosm they summarize what’s going on in fashion today. That, in itself, is why they are now being given so much attention, because they feel relevant and exciting and new. Frequently, newer than the catwalk collections they are supposed to punctuate, but in many instances, supersede.

Newness is a major reason for the pre-eminence of the pre-collection. It’s something every CEO and many a designer has cited to me as something their clients demand, painting them as insatiable fashion nymphomaniacs driven by an overwhelming lust for novelty. ‘They are excited by new things,’ asserts Toledano, discussing the house’s pre-collections and the fact that Dior product is now spliced into multiple fragments to feed Dior boutiques on a monthly rather than seasonal basis. ‘For us it is six collections a year,’ states Bruno Pavlovsky, president of fashion at Chanel, ‘which means a collection every two months.’ That’s not clothing deliveries, but entire, individually conceived collections. Burke and Vuitton are similarly motivated by their clients’ wants and needs. Burke allowed how, today, people don’t only cruise to warmer climes but, in the topography of contemporary luxury, live there year round. Perhaps that’s why the pre-collections, with their climate-flexing drops of summer knitwear and winter chiffon, nothing too heavy and nothing too light, have become such a vital component of the contemporary fashion landscape. The pre-collections are a no man’s land, the all-important in-betweeners. A leveller.

That seems disparaging – as if pre-collections are fashion’s equivalent to the musical term ‘middle of the road’. They’re not, at least, not any more. Designers like Nicolas Ghesquière at Vuitton and Raf Simons at Dior have made sure of that. I remember seeing Cathy Horyn, then fashion critic for the New York Times, at a show in London. She remarked at how she had seen reflections of Simons’ first Dior cruise show – an easy, breezy Monégasque escapade of patchwork lace and zip-front, free-flying silk – in the collections of numerous other designers. I agreed. ‘That one collection has been a goldmine,’ she commented.

These collections were born in the holidaying wardrobes of those fictional one-percenters with the wherewithal to chase the sun in the winter months.

Cruise collections wouldn’t traditionally be the ones that mass-market retailers (and lesser high-fashion designers) pick over for ideas to filch. It’s all part and parcel of that new pre-eminence of the pre-: when they are being presented by designers of the calibre of Simons, and Ghesquière, and Miuccia Prada (who shows a pre-collection in Milan during menswear for her main line, and butts against the haute couture in Paris to present Miu Miu), you pay attention. That’s a new development, too: before, pre-collections were put together by back-room teams, by people like Julie de Libran, Marc Jacobs’ former right-hand woman at Louis Vuitton, who was solely responsible (and credited as such) for the house’s cruise and pre-fall. She’s no longer with Vuitton; she was lured away to become creative director of Sonia Rykiel, her practical and pragmatic pre-collection approach an attractive proposition for a house looking to reposition itself in the fashion firmament.

As Michael Burke at Vuitton said, pre-collections are no longer an afterthought, but a precursor. They have become the main event of the fashion calendar, both geographically (it takes a while to let the schedule settle, and figure out which far-out locale you’ll be flung to next) and ideologically. You could argue that, today, everything feels like a pre-collection when you wind up touching cloth. Garments are lighter, easier, simpler and, it must be said, commercially enticing. At base, more attractive.

That should be the point of fashion, though: to get these clothes onto people’s backs. Which explains the pre-eminence of the pre-collection. With or without the prefix.