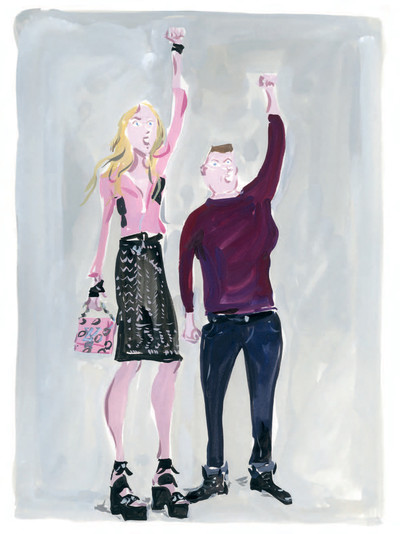

Why 21st-century feminists are replacing hunger strikes with high heels.

By Laia Garcia

Illustration by Jean-Philippe Delhomme

Why 21st-century feminists are replacing hunger strikes with high heels.

One of the first steps to becoming a good feminist is to loudly proclaim a disinterest in fashion. I already knew this, but I learned it again two weeks after we launched Lenny, Lena Dunham’s feminist newsletter, back in July 2015. We posted a selfie Lena had taken on our Instagram account, a close-up of her face wearing a beautiful shade of red lipstick, which I described on the caption as ‘powerful’. ‘I thought this was a feminist newsletter?’ rang the first comment. ‘Disappointing to see such vacuous stuff featured,’ someone else chimed in. The jury had reached a verdict and it told us we could not be politically conscious while having our faces painted. Whatever happened to sisterhood? Do these women not know how hard it is to find the right shade of red lipstick? Not that I was surprised.

Fashion is frivolous. Fashion takes advantage of women’s vulnerabilities. Fashion is expensive and therefore not meant for ‘real life’. Fashion makes women unhealthy. And listen, I’m not saying that the fashion industry is perfect, but so many of these opinions are products of the patriarchy itself. (Patriarchy: once upon a time I would have thought it ridiculous to even say that word out loud, and while I still do, I’m nothing if not self-aware.) Fashion is ‘women’s interest’, so it must be less than, even though throughout the development of Western civilization, men’s costume was often as ornate – sometimes more so – than women’s. In the early 1800s when men decided they needn’t concern themselves with such superficial matters, the dandy emerged. Nearly two centuries later Jean Baudrillard called dandyism ‘an aesthetic form of nihilism,’ and then 35 years later I read that quote and realized it’s not an unrealistic way to describe what being a feminist with a keen interest in fashion feels like.

A few years ago, before Beyoncé performed in front of a giant sign that read ‘FEMINIST’, my friend Tavi Gevinson started Rookie, a feminist website for teenage girls. At the time many people did not take her endeavours seriously. They were already sceptical about her interest in fashion, and they did not think someone so young could be so smart, so committed to creating a space for young girls to just be. One of my favourite things I did while at Rookie was an editorial featuring the artist India Salvor Menuez wandering around a Chinatown mall wearing Mary Katrantzou, photographed by my friend Petra Collins. Petra, whose work has been part of Rookie since the beginning, is now at the centre of a new wave of female photographers whose work is explicitly anti-fashion, not in a 1990s heroin-chic way, but in a way that rejects the glamour, super-vixen, hyper-sexualized tropes that come from decades of seeing women through the eyes of male photographers. That women like Willow Smith and Rowan Blanchard are on the cover of fashion magazines surely owes a bit of debt to Rookie and the world that Tavi dreamed of, and made a reality.

But now feminism is fashion’s navy blue of India! ‘Can you wear lingerie and still be a feminist?’ asks one article. ‘Are high heels feminist?’ asks another, as if inanimate objects can have an opinion or an influence in the fight for the equality of all humans. We have conversations about the lack of racial diversity in fashion, about the need for a variety of body types – of healthy body types – on runways and in magazines. But then Karl Lagerfeld stages a ‘feminist protest’ on the runway at Chanel one season (‘Was Coco Chanel a feminist?’); Demna Gvasalia sends out two different collections with an all-white cast of models and is deemed ‘the saviour of fashion’; and designers churn out unisex clothing that they now call ‘genderless’, as if a knitted sweater and matching trousers will make trans people’s lives better.

‘At least we’re having these conversations!’ some say, in the same tone they might use to tell their child who placed last in the school race, ‘At least you gave it your best!’ But it’s just not enough. ‘Put out or get out!’ If a teenage girl from a Chicago suburb was able to visibly change the landscape, then truly what excuse does a powerful corporation have? Attempt to understand the problems and find real solutions for them, or at least own up to the fact that the world is changing and you’re just coming along for the ride. Yes, these are important conversations, but talking about the same thing all the time without doing anything about it is just really boring.