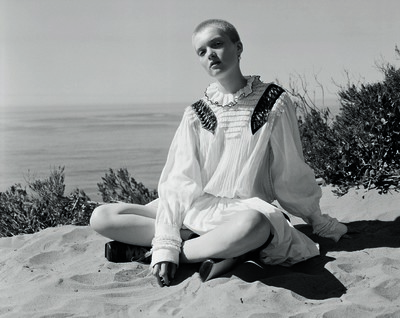

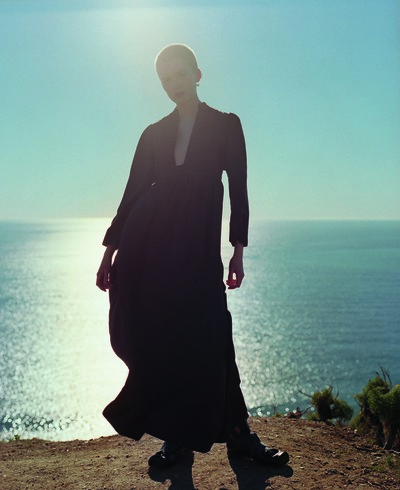

This season’s trip back to the future.

By Alexander Fury

Photographs by Zoë Ghertner

Styling by Jodie Barnes

This season’s trip back to the future.

In the early 1980s, Italian designer Gianni Versace came across a German aeronautic technique that created a pliant metallic mesh. He used it to make a series of simple, sensuous draped garments, which sold well, especially in America. In Versace’s boutiques in Miami, Scottsdale and Rodeo Drive, more metallic mesh clothing was sold than the rest of the collection put together. It outfitted women like historical heroines, in chainmail like that worn by medieval knights. Fashion allowed those American women to buy into a fantasy past, to discover it anew, to relive it. It’s a bit like cosplay, or those renaissance fairs that are, again, very popular in the United States, where check-out clerks and middle management can dress as swooning damsels and dashing troubadours, and check out from daily life. Escape.

Is that, perhaps, the same route high fashion is taking? Escaping its present by borrowing from history? If so, that’s nothing new: most styles in fashion can be traced backwards easily. Shoulder pads emulate the 1980s, in turn inspired by the 1930s. Platform shoes recall the 1970s, themselves reminiscent of the 1940s. Bias-cutting is 1920s, via 1990s, diverted through the 1960s. Even the future – sci-fi, plastic fantastic, optic white go-go booted – is founded in a vision dreamed up by André Courrèges and Pierre Cardin in 1965 and intermittently revived ever since. Nothing is new; everything has been done before.

The difference, now, is that the roundabout of revival of more recent revivals has, seemingly, burned itself out. Designers are now plunging further afield, ransacking more distant history, to create garments that, ironically, feel fresh and different. That difference comes from distance, rather than innovation. Memory is fleeting – fleeting enough to forget the true origin of corseting of a Tudor décolletage or the heft of a 19th-century gigot sleeve, and to register them as something new, and hence something appealing. That’s all part of the chimera of fashion.

Is it worth padding through fashion’s recent revivals? There have been the medieval styles of Raf Simons’ final Dior haute-couture collection; J.W.Anderson’s leg-of-mutton shoulders; smocked tunics like Middle Ages peasants at Lemaire and The Row; 19th-century divorce corsets recalled in boned bodices at Céline. None are the obvious, theatrical flourishes we’ve witnessed of the past, when Galliano, Westwood and McQueen resurrected panniers, crinolines, frock coats or doublets as unwearable editorial statements. Rather, they’re subtle digs into history. Unearthing something old, trying to make it look new. Succeeding. Fashion’s narcissism knows no bounds. It is fixated on its own sartorial reflection, forever flicking through past images of itself, and thinking, ‘Didn’t I look great?’ Nevertheless, to fashion the past isn’t a dead, archived image, something held at a remove. It is a commodity. The past is acquired by fashion, loaded with symbolic value.

Anyway, those were the thoughts of the Marxist theorist Walter Benjamin. He was obsessed with fashion – specifically with fashion’s ‘sartorial quotes’ of its own history, its perpetual use of its own past to create its own future. Benjamin saw that, philosophically, as fusing the eternal (history) with the ephemeral (contemporary fashion), appearing new in contrast only with that which has ceased to be fashionable. If you read further into it, you see the roots of the styles, but on the surface, they seem different. That chimes with French postmodernist theorist Jean Baudrillard’s assertion of modernity, signified by fashion, as a simulation of change, ‘a dynamism of amalgamation and recycling’.

To fashion the past isn’t dead. It is a commodity. The past is acquired by fashion, loaded with symbolic value.

The gist is thus: if you were to wear a precise recreation of, say, a bustled dress of 1883, your garment would be read as fancy dress. You’d look a fool. But if a garment is quoted – mangled and mauled by the vagaries of the contemporary, accented with current vocabulary and otherwise translated – it has been alienated from its origin, and activated for the present. It becomes not costume, but fashion.

The line between the past and the present is the malleable thing. How much difference does there need to be between the precise recreation and the contemporary reimagining? Versace’s slinky evening dresses were hardly about historical verisimilitude. Others, however, strive for absolute accuracy. Vivienne Westwood, for instance, has designed garments that have recreated historical clothes down to reproduction Lyon silks9. Even her unusual, often strikingly modern clothes are embedded in history. Westwood’s dissection of archival patterns allowed her to incorporate elements of costume into her fashion – an 1890s sleeve meeting a 16th-century bodice, with a petticoat from the Second Empire. The result is a fusion, born from history but which could never have happened any time but today.

‘At the “Pirate” time, looking at history… I really tried to copy the historical garments, and I still do,’ Westwood once told me. She was wearing a draped dress criss-crossed with bands of cloth, which looked a bit like something someone would wear in a nativity play. When her shop on the King’s Road was renamed Seditionaries and began pioneering the hard-edged, modernist punk aesthetic, Westwood would discuss how the tartan kilts she sold were based upon ancient Greek peasant costume. ‘It’s the dogma of the last century that you throw away the past,’ Westwood told me last year. ‘But it’s like telling a scientist to throw his laboratory away. If you throw it away, you get rid of all the technique. You have to go back to the past.’

The past lives on in fashion. Haute couture, often vaunted as fashion’s Formula One, is grounded in rules determined 70 years ago, bears a name from the mid-19th century, and is still based on dressmaking methods that date back to Marie Antoinette. Haute couture is living, breathing history: gowns use methods passed down through generations, painstakingly sewn by hand – as if sewing machines had never even existed. The women who still wear it – 800 to 2,000 worldwide – are a direct link to a grand tradition of society hostesses, celebrities and princesses. They are clad in fashion’s storied past.

Perhaps that’s why couture, of all forms of fashion, most frequently harks back. These dresses are created for women whose cloistered, pampered and privileged lives more closely recall those of historical figures – Madame de Pompadour, say, or Empress Eugénie – than you or I. Their social engagements necessitate ball gowns and opera coats, suits worn once, to travel, then discarded. That kind of profligacy belongs to another time, an era when etiquette decreed 18 pairs of gloves scented with violet, hyacinth or carnation and four new pairs of shoes had to be ordered for Marie Antoinette every week, whether she wore them or not. I once saw a pale pink Christian Lacroix haute-couture evening gown hanging in the London wardrobe of couture client Daphne Guinness. It was corseted, bustled and spangled, like something from a James Tissot painting. It was eight years old at the time. She confessed it had never been worn.

For many, the 1920s recall not the original, but fashion’s recent simulacrums — the Technicolor jazz age of Miuccia Prada in 2011.

Walter Benjamin didn’t live to witness the rampant revivalism that characterized fashion of the late 20th century, the nostalgia and historical fixation that drove fashion, like Gatsby, ceaselessly into the past. Today, fashion is driven back further because so many have pillaged the recent past. To reference the 1920s recalls, for many, not the original, but fashion’s recent simulacrums – the Technicolor jazz age of Miuccia Prada in 2011; Galliano’s garçonnes in the 1990s. It becomes not a historical reference, but a fashion reference. Not a recollection of a distant, non-experienced past, but of a recently remembered time. Anonymity permits escape and imagination of better times and better clothes. Fashion’s cannibalization of its own past means that the past is remembered not for the original period, but its subsequent reflections.

Contemporary fashion collages together details culled from differing historical sources. Vivienne Westwood’s notion of studious accuracy is eschewed, in favour of vague remembrance and reference, half-recalled clothing distorted in its reiteration. The result? A Frankenstein’s monster, an echo of an echo of a past that could never have existed, because it is a composite created in the present. It has a memory, too. The glass of fashion distorts and refracts images of the past: a leg-of-mutton sleeve today, for instance, is never quite what it was in 1830 – nor in 1890, when the style was revived. It was revived in the 1940s, too, as well as the 1980s. Today, that single sleeve bears the traces of all of those antecedents. It’s a loaded aesthetic statement, ready to be interpreted in a multitude of ways.

Voyaging into a distant, distorted and indistinctly remembered past can render something new, however. New in that the garments themselves – relics of court costume rather than past fashion – cannot be replicated and regurgitated as easy fashion propositions. For starters, there aren’t many of them around to copy, certainly not to rip apart and slavishly trace line for line. Plenty of fashion repeats rather than reinterprets, using an actual garment as a template for a cookie-cutter copy of, say, an Ossie Clark 1960s dress, a Balenciaga mid-century coat, or even the obscure, like army fatigues or Americana denim. Stores like Los Angeles outpost Decades or London’s Vintage Showroom, Rellik and William Vintage, do a swift trade with designer brands, which often rent the garments for a weekly or daily fee, to photograph them on models, examine techniques, lift details. One fashion consultant, who prefers to remain anonymous, told me of going to a vintage warehouse in the English countryside and finding racks of archive garments bearing paper labels of major fashion houses. Those were the last ‘borrowers’ – and the labels warned other fashion houses that these were used goods, for that season at least.

To avoid potential duplication of the duplication – or to prevent others from knowing what has been referenced – some labels purchase the garments, keeping them for reference (and to prevent others from being similarly inspired) or cutting them apart to copy the pattern stitch for stitch. That can be done without destroying the original – ‘pin-through’ copying (literally pinning out a garment through the construction lines onto pattern paper) can trace the blueprint of a garment without the need to unpick the seams. However, cutting apart a vintage piece has an added ‘benefit’ – it erases the evidence of how close a copy may be to the original. According to industry lore – word of mouth from vintage dealer to vintage dealer, with the ring of truth – copied garments are burned by some designers to cover their tracks, leaving only their newly manufactured counterfeit. Which, in a Baudrillardian twist, then becomes the original.

Older history requires further exploration, and modernization. A dress from the 1960s can still be worn, a crinoline or a farthingale less easily. Ironically, the further back you go, the newer the clothes wind up looking, reinterpreted in modern proportions, modern fabrics, cross-bred with contemporary garments. A boned Renaissance bodice becomes a cotton shirt; a voluminous ball gown’s sleeves define the shoulders of a jacket. It requires more work to make these sartorial quotes feel contemporaneous, to pull them out of fashion’s dressing-up box, and make them seem relevant, and exciting, and new.Fashion’s trip backwards is ultimately moving it forwards. It’s indicative of creative grappling with complex notions of modernity, of tackling the challenge to challenge, to excite, to engage. Pulling apart history to make it, rather than rerun a few old classics. Something old begets something new.