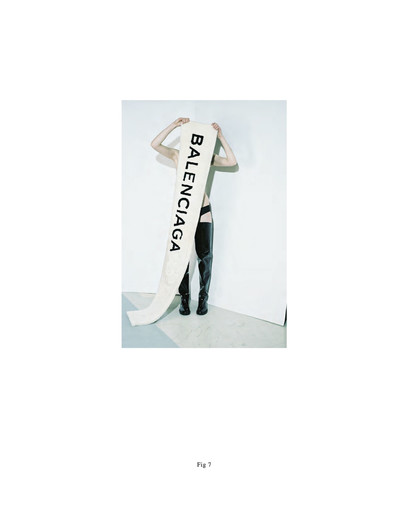

Demna and Mark Borthwick on the joy of filling Balenciaga’s blank new page.

By Jonathan Wingfield

Photographs by Mark Borthwick

Demna and Mark Borthwick on the joy of filling Balenciaga’s blank new page.

“L’esprit Nouveau”

Par hasard

Les œuvres d’âmeLes aventures, ce rêve / parfois égales… parfois non’sense à boire

à voir entre temps sans avoir les conséquences … je suis silence’

chaleurs vivant entre nous sa ressemblance d’éternité …

“l’étoile l’âme oeil seul” … l’âme et caetera’ arrache arrache

arrache… nonchalence’… on s’embrasse les fleurs’…

je danse dans les champs de lavande’ par conséquence

non’chalence “se lache se lache se lache” je t’embrasse

c’est vivant - c’est vivant - c’est vivant

val de cœur ‘

xEVERY SOUL’S VOICE AN INDIVIDUAL’S DIVINE INTERMISSION THAT’S CALLED UN’KNOWN

It’s 7pm on a Saturday night on Rue du Cherche-Midi in Paris’ sixth arrondissement, the eve of Demna Gvasalia’s debut show for Balenciaga. Sitting around a long table in the house’s design atelier, sharing a bottle of wine, are Gvasalia and photographer Mark Borthwick. There is an overwhelming sense of calm. Silence even.

When Gvasalia – best known as the creative face behind fashion collective Vetements – arrived at Balenciaga late last year, among his first initiatives was to contact Borthwick, who he had never met, but whose work he admired for being photography that expressed mood more than product.

Demna subsequently invited Mark to join him on his Balenciaga journey. Not documenting the new era exactly. Nor creating formal fashion imagery. Rather,

just doing what came naturally in the moment. Which has always been Borthwick’s way of working, a non-method that first produced his ever-influential, colour-saturated, ‘accidental’ aesthetic in the 1990s.

As we begin chatting, Lionel Vermeil strolls in and joins us. An industry veteran, who was at one point Balenciaga’s communications director, before recently becoming the uniquely titled Director of Fashion and Luxury Intelligence at Kering, the group that owns Balenciaga, Vermeil was instrumental in Gvasalia’s appointment.

The house of Balenciga considers the Georgian designer’s arrival as a continuation of its own history, one founded on the shifting rapport between pure craft and commerce, the avant-garde and products. Indeed, with his experience at Margiela, he certainly brings the unorthodox back, but the house was also shrewd enough to take into account the time the designer spent at Louis Vuitton. In other words, Gvasalia understands that any radical creative warp always needs to be woven into the weft of the luxury business.

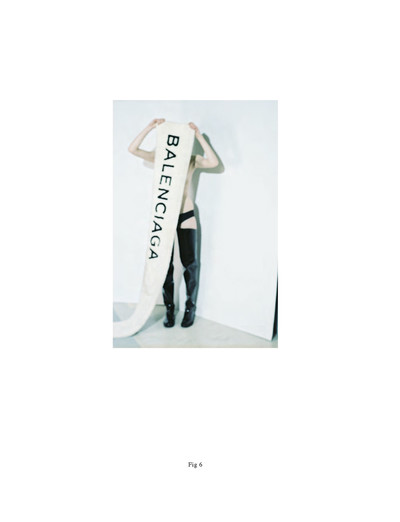

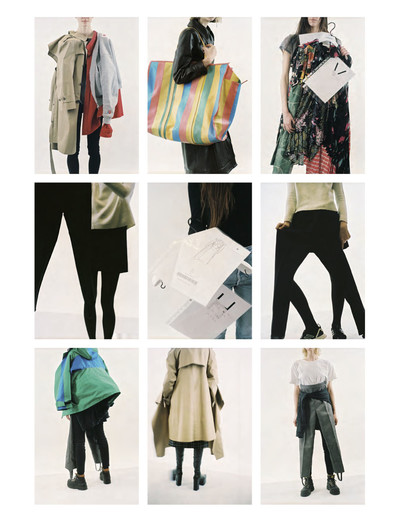

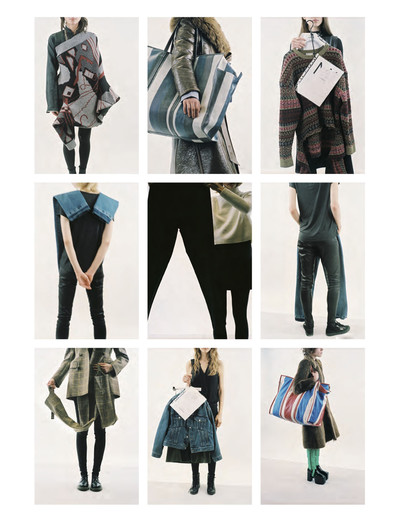

That said, the work that Gvasalia and Borthwick have been quietly producing since late last year is a reflection of their shared creative process: freeform, revelling in carte blanche, while revealing a studious return to Balenciaga’s forward-thinking fashion and design purity. For the moment, neither Gvasalia nor Borthwick know exactly what their collaboration will result in. An advertising campaign, a book, an exhibition? All three? It might simply turn out to be a creative exercise in tone setting, a partnership that helps Gvasalia shape his vision for the house. As Borthwick says, ‘Photography is less about documentation than it is about a shared experience’.

The resulting conversation and portfolio gives a first glimpse inside a creative process as it is happening, a taster of a new vision of fashion, as well as a clue as to why fashion houses such as Balenciaga sense that creative freedom is the best route back to relevance.

‘Paris is a tough city to live in. People don’t necessarily smile here, they’re always grumpy, and I think that inspires me.’

Jonathan Wingfield: Demna, when you think of Mark’s work what does it evoke?

Demna Gvasalia: Freedom is a good word to start with. Arriving here at Balenciaga really felt like something new, something free, like a blank page. I said to myself, ‘Who am I going to work with?’, and the first person who came to mind was Mark, for exactly the reasons you’d imagine: his work captures freedom, intimacy, warmth, experiences. And I felt that collaborating with Mark – I wouldn’t even call it collaboration, because it sounds a bit formal – would be the best way to bring out the beauty of what we are to doing here at Balenciaga.

Did you have any preconceived ideas of how you wanted to work with Mark?

Demna: I didn’t even have a clear idea of the collection, let alone what Mark was going to shoot, so it started from zero and became something. With the pre-Fall collection last December – which was not really my collection and didn’t represent my vision – working with Mark became something of a transitional exercise. He and I basically got to know each other while we were doing the very first day’s shooting, and it was a brilliant experience: we shot in the Balenciaga archives, modernizing them through images, and we had a lot of fun.

Was there a particular piece in the archives that caught your eye or that you felt a connection to?

Demna: I felt more of a connection when I actually held up certain pieces on their hangers and realized how heavy they are. In the images of them that we see in fashion-history books they seem so light. I think that is the magic of Cristóbal Balenciaga and what makes the work he did so modern: he didn’t want women to suffer; he didn’t want to put a corset on her; he made this dress so she could actually be quite round and still feel elegant in that retro way, but at the same time comfortable. She didn’t need to go to the gym to be able to wear that dress. That surprised me.

You mentioned before that you had a lot of fun shooting in the archives. Curiously, the word fun rarely gets used when discussing fashion these days.

Demna: Oh, it was great fun, lots of fun, screaming, drinking, smoking, talking. We didn’t work, you couldn’t call it that… It’s like this with my other brand: I work with people who are my friends, and they’re from my generation. Obviously, with Mark and Balenciaga, it’s a different thing, but I was so impressed that the same feelings could be experienced.

So that first shoot was the first time you’d met Mark?

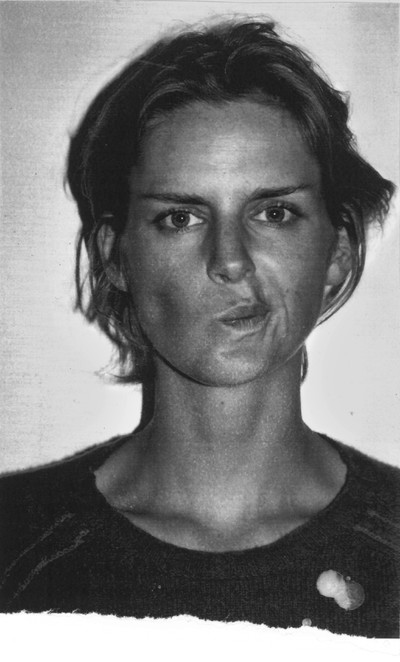

Demna: Yes. I was always very aware of his work, because I had worked at Margiela. When I started Vetements, two and a half years ago, the first image I put on my mood board was an old portrait Mark had taken of Stella Tennant.

Is it the one in which she’s kind of biting the inside of her mouth?

Demna: Exactly. She was elegant, and she was fun in that picture…

Mark, can you remember the day you shot that one?

Mark Borthwick: Absolutely, yes. It was a really fine afternoon with Stella; she had popped over for a cup of tea. I think that we had just finished shooting something ‘serious’ and she then wore a bunch of T-shirts and I shot a roll of film. It was a moment of chance when something special took hold of me.

Mark, to what extent were you aware of Demna’s work prior to meeting him?

Mark: It was completely unknown territory until I was introduced to it by my children. My daughter Bibi is quite good friends with Virgil, who does Off-White, and through Virgil there was a connection to Vetements, and then Demna. I was surprised by the parallels between Vetements and what my son Joey is into. He’s an 18-year-old kid growing up in New York who is completely besotted with the whole philosophy behind Supreme – the way that brand is collaborating continuously and touching upon everything that is happening right now. The minute I first saw Vetements, it felt like something relevant, not because it was similar to Supreme, but because it was functioning completely outside the confines of the fashion industry. It had that kind of transparency and innocence, naivety and fragility to it that made you want to love it, made you want to smile, made you want to be part of it.

‘The minute I first saw Vetements, it felt like something relevant, because it was functioning outside the confines of the fashion industry.’

What do you think about Demna’s world in the context of Balenciaga?

Mark: Well, aesthetically, the idea of Demna at Balenciaga just brings so much excitement to the idea of doing something that is real. I mean, that is where I’ve always come from, but it is inspiring to see real actually exist, without being a preconceived idea or simply following in the footsteps of something that’s come before. As a reflection of the industry today – especially living in New York, where nobody is prepared to bring the fashion itself into a context that is real – what Demna is doing is really beautiful and important.

Demna: For me, the ‘real’ that Mark is talking about comes from the rapport between the person in the picture and the garment. That’s what always interests and inspires me. That’s exactly what I am trying to do at Balenciaga: find this new relationship between how the woman and the body and the product interact. It feels exciting to be planning how we can define this interaction at Balenciaga.

You use the term ‘product’ quite overtly. Some people consider it almost a dirty word.

Demna: Well, I am a very product-oriented designer. I mean, my other brand is called Vetements! But the product doesn’t exist without the person who wears it, so it’s how you bring the two of them together that counts.

Mark: It’s a beautifully fine line, because right now, this evening, the new Balenciaga woman doesn’t even exist yet.

Demna: That’s what’s most exciting about right now.

So you don’t yet know how she is going to be depicted, but something is going to come out of that process?

Mark: Yes, I mean it is an extreme clash of aesthetics that’s going on here, and that is where it is really masterful.

Demna: I’m sometimes asked, ‘Who is the woman you design for?’ But I don’t design for a specific woman. I make clothes I see myself as a dressmaker rather than a designer or a fashion designer – and then the women who those clothes appeal to will naturally become the ones we make them for. That gets defined after we make the clothes, and so depicting that in the visuals is very much a part of that discovery.

Lionel Vermeil: When I started in this business we called the people making clothes créateurs. You had the couturier and you had the créateur. Then it was the creative director and then they became ‘artists’. But now Demna has moved away from all of that. He calls himself a dressmaker, not pretending to be anything else. He is making clothes to be worn.

Demna, was it important to you that Mark’s pictures even depicted the first collection? Was there any specific brief?

Demna: Mark didn’t even see the collection until two days before he started

shooting, and I don’t think we need to define anything beyond this pictorial freedom – that’s all that counts.

Mark: As far as I’m concerned, we’re kind of making it up together; there’s a lot of joy and feeling in the process. I certainly like to take a role in participating with the clothing: I find that the extraordinary casting that Demna has orchestrated is unbelievably relevant to the garments themselves, and to creating an identity for that new Balenciaga woman.

Again, the word joy that you’ve just used seems particularly relevant: it could be construed as naive, but you’d presume that any successful collaboration would be born out of a shared joyful experience.

Mark: In the very first minute of the first conversation we had together, it was made clear: ‘We’re going to have fun’.

Demna, Mark referred to your ‘orchestration’ of the casting. Could you talk a little about this, because it is obviously so central to what you do?

Demna: It is about the credibility of the woman who wears those clothes; it has to look believable on the woman when she wears a particular garment – that is the most important criterion for us. The key is character casting, and not just putting the clothes on blank models who you’d never expect to see wearing them in real life. The models need to feel the clothes that they wear. Many of the girls we’re using have actually said, ‘Oh, I love my look’.

Tell me about when you first arrived here at Balenciaga, about the conversations that you were having at the house?

Demna: I went into the archives and I had a look at all the periods of the house – from the very beginning up to now. It was an extremely informative day for me.

Lionel: I remember you had a specific way of looking at the archives; like taking pictures, but not of the piece itself…

Demna: I already knew most of the Balenciaga archive pieces from books and imagery, so while it was very exciting to see them in real life, it was more about understanding why and how they were made. I was keen to understand Cristóbal Balenciaga’s approach: how he worked with women, his relationship to the body, the weight of the garments, the proportions. In his era, of course, there were different things that influenced the rapport between the body and the garment: he would open the collars to show the jewellery, or shorten the sleeves, which today wouldn’t be so relevant. It was nonetheless important for me to understand the methods that he used and then to think about how they could be applied in 2016. I like to make clothes that give women an attitude, while being refined and elegant in a modern way that doesn’t fall into ‘past elegance’.

How would you define modern elegance?

Demna: Elegance used to be associated with something quite soft, and I think in recent times it’s become harder, stronger, more aggressive in a way. I think aggressive is definitely the right word to associate with modern elegance. And in a way there is a certain aggression that naturally comes with the girls we’ve cast for tomorrow’s show.

Mark: But there is still something quite noble about them. They are characters unto themselves and they don’t feel controlled.

‘Elegance used to be associated with something quite soft, and I think in recent times it’s become harder, stronger, more aggressive.’

Mark, you’ve been working in fashion for many years – firstly as a make-up artist in the 1980s, then with your photography, which really emerged in the 1990s. How do these experiences give you a framework not only to understand the industry, but also to enable you to deconstruct or reconstruct that in your photography?

Mark: Curiously, what we’ve been doing today for Balenciaga feels like a subtle reflection of many experiences that have occurred to me over the years. And I love that distant familiarity becoming something totally new and fresh. I was there photographing the collection, but the collection enabled itself to become something else; and that freedom reminds me of sensations I felt maybe 15, 20 years ago. But it has greater meaning now; when I was younger, maybe I didn’t even see it in that context because it didn’t have a sense or a meaning back then.

You once made a photographic series of ‘fake ads’ – placing fashion brand logos on very calm and empty street images – in doing so altering the images’ meaning, questioning what those brand logos stand for, and so on. To what extent are the images you’re making now altered by their being framed within a Balenciaga project?

Mark: Advertising itself has become so conformist; so much about selling commodities. I have always been more inspired by the notion of removing everything to give some meaning. In doing that, I encourage it to become something else, something new, and something fresh, which seems important when you consider how so much advertising is just a question of filling and filling and filling the space. But I just don’t see the world in that way. The pictures I take exist because control has been removed, or not even considered. The feelings in the pictures come through because of the shared experience with a stylist or a friend or the person I am photographing. So, to answer your question, the Balenciaga frame doesn’t even really exist at this point.

So much of your photography is about what is not in the picture; there is that really beautiful sense of absence. So I was interested in discussing how a brand’s products – Demna’s word – can be expressed through absence. Is this something you’re even conscious of?

Mark: I think I learned a lot of lessons when I was a young photographer, being up against a certain set of rules and how in your own world there shouldn’t be any rules. I was put in situations where I was seen to be breaking the rules, when I was told, ‘You can’t do that’. But ‘that’ – whatever it is – shouldn’t even exist in your own world, it shouldn’t even be something you question. So the absence comes from simplifying the picture, showing it as purely as possible, removing all traces of someone else’s rules.

Demna: I think the absence in Mark’s work has so much presence. I feel like you don’t need to have a product. The absence makes you question things and it hits you much deeper than just on the surface where you say, ‘OK, that’s a bag’.

‘Advertising has become so conformist. The pictures I take exist because control has been removed, or not even considered.’

Although the bag seems to have become a cornerstone – maybe even a necessary evil – in the language of modern fashion advertising.

Demna: Which seems so not modern. Especially when you consider some of the original campaign images from Cristóbal Balenciaga’s time. One is just white with only the label; another is a picture of the room in the original Balenciaga space where there is a sofa and two women sitting on it – probably dressed in Balenciaga, but you wouldn’t know because the picture is so small. You can just see that something is happening there, but it’s so restrained, so quiet and refined. I mean, you would never see anything like that now. There was no product. It comes back to Mark’s pictures: it is what you don’t see that holds a desire and an interest, and that is something that I love.

Mark: That is an interesting point, because if you liberate the image and take everything away it is completely free, and you can encourage it to interpret whatever you want. And I think that is the space where we are right now with this project.

In that it feels liberating?

Mark: Yes. I think as a young photographer I found it really complicated being told that you can’t be free, you can’t break the law, this has to be one look, and so on. So my reaction is always to simplify, get to the essence, don’t get distracted by the rules.

Did you always feel like that, or was it only since you started working in fashion?

Mark: I think it is genuinely innate as to who I am. And you become who you are, thank God; maybe you are not aware of it when you are younger. But it is interesting when you start getting a bit older and you have children: you learn so much more from listening and it is that soft, really quiet space, through the listening that there is beautiful absence.

Demna, tell us about your surroundings and your life when you first started expressing yourself creatively. Are there elements of that time that still inform your work now?

Demna: I was drawing, always, but I think what influenced me most in the way I work creatively now was the absence of certain things. I grew up in a post-Soviet country that was deprived of a lot of information until the beginning of the 1990s. So this absence and the lack of resources really motivated a hunger and desire for discovering things. We literally had to buy magazines on the black market if we wanted to find out what was happening beyond our very sterile, culturally and socially closed space. Once that period was over I faced a time at the beginning of the 1990s when there were many different directions in music and culture suddenly available for me to investigate: warehouse parties, rave, goth, hip-hop. I did the whole thing.

‘Growing up in a post-Soviet country, we literally had to buy magazines on the black market if we wanted to find out what was happening.’

So you were kind of culturally promiscuous.

Demna: Yes, which I see as a virtue now. But I got into them all at the same time, so I wasn’t just dressed as a hip-hop teenager; I was dressed as a mix of all of that, and that sense of mixed influences – the patchwork – definitely continues to inspire me.

When you look back at that time now, would you say you were rebellious?

Demna: Not at all, I was afraid of everything, until suddenly everything became possible and I kind of discovered myself with that sudden clash and explosion of possibilities.

Since then, have you had to exercise restraint or do you try to replicate that sense of abandon and wanting it all?

Demna: I try to replicate it and I realize that’s part of my character as well now, so there is nothing I can do about it.

What about you Mark, when you were younger, did you consider yourself rebellious?

Mark: No, I wasn’t rebellious about anything whatsoever. But I think that is because I lived in the middle of it all. I grew up just off the King’s Road: my parents were a little bit older, but they were really free, and I think they found it exciting to see this whole new generation of young kids on the King’s Road, going through the punk movement, through New Romanticism. I was this young kid who came out of all that: I was 16, 17 at the pinnacle of the punk movement. Then I started wearing make-up, living in squats, and I dressed as a girl or a boy – as a New Romantic – for a good six years, and that’s what led me into make-up and fashion. But again, there were no rules, and if there were, they were there to be broken.

So you were brought up in an environment where freedom of expression was actively encouraged.

Mark: Yes, very much so. Especially from my mother’s side, she was the one who enabled it. Which helped me understand that you didn’t have to rebel for the sake of rebelling, because I was surrounded by people who were very curious themselves. I was exceedingly curious, very innocent and naive, and also quite fragile because I didn’t know who I was. I started wearing make-up every day; it was the first time when it didn’t matter if you were gay or straight because you could be anything, and that was really liberating.

Demna, did your family encourage freedom of expression, despite the culturally restrictive era?

Demna: No, not at all, it was very constrained. I definitely had to go looking for it; I can’t say I found it indoors at that period, definitely not.

And what does freedom represent to you now, in terms of your work and how you want to express your ideas?

Demna: Freedom really represents the idea of enjoying what you do. I would never be able to force myself to do something. I love my job every day and I don’t even consider it a job.

What about you, Mark? One would presume that freedom is one of the driving forces behind your photography. Is that a conscious thing?

Mark: No, I don’t think it’s conscious; I think it’s a state of mind. As I mentioned before, having kids is a way of reflecting and approaching life that liberates any sense of conformity. As you get older, you do realize that everything you do comes from yourself, and that instils an incredible amount of freedom. And I think if you can project that onto your family and friends, and everybody around you – and especially on a shoot or any creative or artistic venture – it inevitably becomes a reflection of yourself.

Demna, you mentioned earlier the notion of product. What were the first products you were thinking about when you first arrived at Balenciaga?

Demna: The first thing I thought was Balenciaga is a house that should make clothes that women, and men, want to wear, that are desirable as products. I’m talking specifically about clothes that we put on our body, and not simply shoes and bags. That’s the priority in my creative approach here: I want to bring it to the point where people really want to have these clothes; I want them to be desired and relevant and speak to people. So I started this season by making a very dry, A4-length list of clothing – a pea coat, a double-breasted coat, and all that – because that’s the skeleton of it.

The first thing I thought was Balenciaga is a house that should make clothes that women, and men, want to wear, that are desirable as products.’

From there, you set about creating a reality.

Demna: Yes, so I said to myself, ‘How do I make a pea coat for Balenciaga in 2016?’ Compiling the listing of garments is only one percent of the process; the other 99 percent is cutting things and working on shapes, because mine is a very architectural approach in terms of the construction of the clothing. The concept of each garment is a 3D approach for me; I need to find something new in the process for it to be credible as a Balenciaga product today.

When you consider Cristóbal Balenciaga’s own work, do you feel that this idea of sculpture and the architecture of the garments to be key for you, too?

Demna: It was one of the key ideas, yes. But it is also the way in general that I work – with volumes and shapes, and sculpting the clothes onto the body, because that is what interests me in fashion and design. That’s why I think I found a good match here at Balenciaga.

Lionel: Through your work and the collection you’re showing tomorrow, you’ve made me realize something. For a long time, I was trying to pinpoint why Balenciaga was such a legend. If you think about Cristóbal in his time, he was doing couture but he was not the only one. So on one side you have Christian Dior who developed a very couture silhouette and a couture way to wear it, because of the corsetry inside, so the silhouette was also the way to wear it. And then on the other side you have Gabrielle Chanel who was less couture and more sportswear, and the way that people wore Chanel was freer and more comfortable. And Cristóbal was right in the middle – a couture silhouette, but a totally sportswear way of wearing it. You’ve made me realize this, Demna. And that is why Christian Dior and Chanel considered Cristóbal superior to them. How to keep a couture silhouette, but still be able to have a modern attitude in it…

Demna: You have to be able to move in the clothes, be able to drive a car in them, and so on, but the other important element, in terms of architecture and working around the silhouette, is the attitude. I mean, that is very present when I work on my own label, and here at Balenciaga the challenge for me was to discover that kind of refined couture attitude – a couture in today’s terms. Sure, couture can be beautiful embroidery but that’s not interesting to me; it just doesn’t excite me. The attitude is what makes it couture, and that is what we really tried to put into the construction of the garments. So even if you are a ballet dancer, when you put that coat on it’s going to give you that attitude.

Mark once said in an interview, ‘When I take pictures, a lot of things happen by surprise’. Demna, what things have surprised you since you started working at Balenciaga?

Demna: What really surprises me is that we have been ready for the show since four days ago; I thought we’d be designing the collection right up to the last minute.

That surprised me, too. When you asked for this interview to take place the night before your first ever show for the house, I almost e-mailed back to say, ‘Are you sure?’

Lionel: I’ve been working for 30 years in fashion and I have never seen this. But that maybe says a lot about fashion right now. You know, that whole last-minute diva chaos of working all night long has always been the norm for so long – we’ve just accepted it’s that way – but I sense the new generation doesn’t want to be like this anymore. They don’t want to get into this industry for that old cliché; they come for other reasons.

Lionel, what was it about Demna that appealed to you and Balenciaga?

Lionel: We obviously loved his work at Vetements and we love his personality, but above all, we sensed that there was a real feeling between his work and what we know about Balenciaga. More like spiritual connections, the way he is acting and doing his work, not the clothes, but the way Demna is working. That was the key. Sure, I know some people might say, ‘Oh yeah, you’re just taking the trendy guy from the trendy brand’, but every big house has been ‘trendy’ at some point. I mean, in 1947 the New Look collection at Dior was the trendy thing, and when Gabrielle Chanel came back in 1954 she was the trendy house of the moment. But I have the feeling that this is something bigger than trends. There is something deeper.

Demna, what do you now know about Cristóbal Balenciaga that you didn’t before arriving here?

Demna: I was surprised by how business-minded he was. He wasn’t just about making beautiful clothes, he was very business-oriented, too. I realized this when I discovered all these other cheaper lines in Spain that he was doing. I know that it was Yves Saint Laurent who invented ready-to-wear, but when you go really deep into the research of Cristóbal, you realize that it was kind of there already.

Did that influence the way you went about designing here at Balenciaga?

Demna: As I mentioned before, I make clothes to be sold and worn. There is no pretence. It has to be desired by someone, bought and worn to death. That would be the best compliment to me.

Mark, what has surprised you about this project so far?

Mark: I am truly pleasantly surprised how relevant it is. I arrived here last Saturday and we did a series of photographs together on Sunday and it was the first view that I had of three or four pieces from the collection, and they really explained aesthetically an idea of the collection itself. If you put those together in the streets, they create something that is exceedingly contemporary in a very couture aesthetic without it being couture itself. And that encourages another way of looking at clothing itself and of looking at the way that people are dressing today. I think we are at a really interesting time today – kids are suddenly dressing up again, the same way as when I was a kid! Not because they’re trying to repeat punk or New Romanticism, but because everyone is creating their own identity again.

Why do you think that is?

Mark: Out of a sense of boredom, because there is very little out there, so why not just be creative with what you have? You can do anything again all of a sudden. There are no rules; there is no one saying you have to dress like this.

Demna, is it important for you that your collections for Balenciaga help women stand out?

Demna: Not necessarily to stand out, but to feel different and feel better when they wear those clothes. I mean, I get inspired by the most normal things you see on the street: a T-shirt can inspire me far more than the drape of a beautiful dress.

‘I certainly learned a lot more about photography the minute I stepped out of the fashion industry; now I photograph everything I love around me.’

What do you see on the streets of Paris that really inspires you?

Demna: The attitude! Maybe that aggression and this couture attitude I was referring to comes from seeing that grumpiness, because Paris is a tough city to live in. People don’t necessarily smile here, and I think that inspires me more. I mean, when I am happy I don’t really want to do things associated with fashion or work, I just want to be happy.

Now that you’re working on two different brands concurrently, does that immediately inform and influence the way that you go about organizing your time?

Demna: In general, I hate time.

What, the lack of it?

Demna: Just the concept of time; I’ve never owned a watch in my life. Time is stress, and I am the most impatient person in the world and I want everything to happen now. I hate the notion of maintaining that rhythm of time, but I definitely have to consider that it exists in real life, the physical life that we occupy.

Do you consciously take time off from work?

Demna: I can only have a certain amount of time working here, a certain amount of time there, but I also make sure I have a certain amount of time of me not working. Meaning I try not to work weekends, for example. I try not to do anything related to fashion at the weekend: just see my friends, watch movies, eat pizza, cook and to do things that actually feed you as a person. Otherwise you just become a robot checking the time, and that is destructive for anyone. Working in fashion, there is always a schedule and time constraints, and while I know I need to consider these things, they are not my priority. That is why I don’t wear a watch.

Still, you managed to complete the collection with four days to go.

Demna: After this interview I’m off to the ateliers, to celebrate with the team as they finish the retouching of all the looks for tomorrow, which is unprecedented for them. They are all so confident; they can’t believe it. They are getting stressed because there is no stress!

People often focus on the dynamic of Vetements as a collective, how you’ve surrounded yourself with people very close to you and just this whole idea of the shared creative experience. How has that influenced the work and the process here at Balenciaga?

Demna: Well, the first thing I asked for before I arrived here, was to move all the designers onto the same floor because it used to be very separated and there was no exchange. But the exchange is what makes the final result of the work so objective, because we talk, we question, ‘Do you like it?’ ‘No I don’t.’ ‘Why?’ We have arguments; we discuss everything. And the talking influences the final result – the product. It actually speaks to a wider range of people because it doesn’t come from just one vision; it comes from an exchange. I think that is really crucial.

As for you Mark, the notion of family and friends seems extremely important in your work; over the years you’ve formed close working relationships with your subjects, such as Chloë Sevigny, Stella Tennant, Cat Power, and now you’re working and collaborating with your own children. Tell me about that shared experience.

Mark: Well, I certainly learned a hell of a lot more about photography the minute I stepped out of the fashion industry; my photographs have become a daily practice, and I am photographing everything I love around me. So it becomes a reflection of myself, my family and all my friends, and everything that just happens. And I learn so much from listening to the photographs and seeing where they were leading me, rather than having any kind of aesthetic control over them.

Freeing control makes better results.

Mark: It’s always been about trying to encourage the mistake, especially with photography.

Give me an example of that.

Mark: There was a certain time that I remember when my son was young and I would walk him to school every day; it was so much more fun to go on this adventure with him and not necessarily get to school on time because that really didn’t matter, it was just about having time with him. We had this period of 30 or 40 minutes where the two of us could just have an experience and that experience was reflected in the photographs I took. But it got to a point where I realized I had to stop myself, because I was shooting two to three rolls of film every day just on the way to school. So I limited myself to taking one single picture on the way to school, and one on the way back, but those pictures had to be something I had never done before. I started looking at things in a different way and tried to encourage the camera to capture that difference – looking at my son in a different way or the light or the streets. All of a sudden, in among all the other pictures I was taking, there would be a random picture and I would look at it and think, Where did that come from? And it’s that unknown territory that kind of alarmed me and was quite sophisticated, and that encouraged me again to see things in a different way.

Demna: He is so lucky your son; my father always said we had to be on time!